Abstract

Gram-negative bacteria pose an increased threat to public health because of their ability to evade the effects of many antimicrobials with growing antibiotic resistance globally. One key component of gram-negative bacteria resistance is the functionality and the cells’ ability to repair the outer membrane (OM) which acts as a barrier for the cell to the external environment. The biosynthesis of lipids, particularly lipopolysaccharides, or lipooligosaccharides (LPS/LOS) is essential for OM repair. Here we show the phenotypic and genotypic changes of Escherichia coli MG1655 (E. coli) before and after exposure to short-term aerosolization, 5 min, and long-term indoor aerosolization, 30 min. Short-term aerosolization samples exhibited major damages to the OM and resulted in the elongation of the cells. Long-term aerosolization seemed to lead to cell lysis and aggregation of cell material. Disintegrated OM rendered some of the elongated cells susceptible to cytoplasmic leakage and other damages. Further analysis of the repairs the E. coli cells seemed to enact after short-term aerosolization revealed that the repair molecules were likely lipid-containing droplets that perfectly countered the air pressure impacting the E. coli cells. If lipid biosynthesis to counter the pressure is inhibited in bacteria that are exposed to environmental conditions with high air velocity, the cells would lyse or be exposed to more toxins and thus become more susceptible to antimicrobial treatments. This article is the first to show lipid behavior in response to aerosolization stress in airborne bacteria both genotypically and phenotypically. Understanding the relationship between environmental conditions in ventilated spaces, lipid biosynthesis, and cellular responses is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance. By elucidating the repair mechanisms initiated by E. coli in response to aerosolization, this study contributes to the broader understanding of bacterial adaptation and vulnerability under specific environmental pressures. These insights may pave the way for novel therapeutic approaches that target lipid biosynthesis pathways and exploit vulnerabilities in bacterial defenses, ultimately improving treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While many efforts have been made to address antibiotic resistance (AR) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG), gram-negative bacteria continue to be a rising threat to public health globally. There are many resistant gram-positive bacteria, but gram-negative bacteria are of particular concern because of the extra protective layer their outer membrane (OM) offers to the cells’ surroundings1,2. One key reason for gram-negative bacteria resistance is its ability to repair and regulate its OM and OM proteins. The biosynthesis and transportation of lipids and proteins to repair the OM of gram-negative bacteria is a mechanism of coping and resistance to protect the cell’s first line of defense. Lipids can patch the OM to support its structure and decrease the uptake of antimicrobials. Lipids have been studied in many bacteria, however, there is a gap in research regarding lipid repair of the OM in airborne bacteria1.

The OM of bacteria is a critical factor in the protection of the cell, homeostasis, uptake of nutrients, and expelling of waste and toxins3,4. Bacterial cells often conduct synthesis of proteins and lipids to repair their OM and maintain homeostasis, or stability in changing environments5. The OM is an asymmetric lipid bilayer comprised of phospholipids and glycolipids attached with lipopolysaccharide, or lipooligosaccharide (LPS/LOS). The production of these lipids is crucial for the survival of gram-negative bacteria. Both are synthesized inside the bacterial cells and are delivered to the OM as needed. LPS/LOS molecules help seal the membrane to protect the cell from leakage or toxins such as antibiotics6.

Under stress, lipid droplets (LDs) in E. coli serve as a readily accessible storage site for lipids, which can be mobilized and utilized to repair damaged phospholipids in the bacterial cell membrane, to help maintain membrane integrity by acting as a “lipid reservoir” for membrane repair7. The composition of the lipid droplets isolated from different strains is highly conserved, suggesting their essential and universal role in bacterial membrane homeostasis8. In addition, bacterial LDs can bind to nucleic acid through the major LD protein (MLDS) and facilitate bacterial survival under stress by regulating genomic DNA function9. Increased levels of LPS, a major glycolipid on the bacterial surface, along with OM vesiculation can deplete the inner membrane, highlighting the need for balanced lipid synthesis across both the inner and outer membranes to maintain the integrity of the E. coli cell envelope10. While the pathways involved in LPS and OM protein assembly are well-characterized, the transport mechanisms for phospholipids (PLs) remains less understood. To ensure the stability of the OM, cells must maintain an excess flux of PLs to the OM, while also returning the surplus to the inner membrane for lipid homeostasis5. Okuda et al.11 demonstrated that export proteins are involved in the transport of LPS across the membrane, suggesting the release of ATP energy to move LPS against the concentration gradient.

Given that most antibiotics target essential processes such as DNA or protein synthesis, targeting cell envelope biogenesis presents a promising approach to combat antibiotic resistance12. Lipid II, a precursor in cell wall synthesis, is targeted by at least four classes of last-resort antibiotics, including the glycopeptides (for example, vancomycin), the polycyclic peptide lantibiotics (for example, nisin), ramoplanin, and mannopeptimycins. Additionally, lipid biosynthesis inhibitors can help reduce the development of antibiotic resistance in aerosolized bacteria13. However, as resistance has developed against all antibiotics in clinical use today, including vancomycin, optimized airflow pattern in ventilated spaces may provide a new strategy to reduce resistance triggered by air pressure.

When E. coli cells are exposed to different environments some of the new conditions include relative humidity, temperature, and pressure changes. A change involving osmotic down shock can trigger pressure changes of 10 atm inside the cell in a matter of seconds. Cells have two options, either to lyse or alter OM proteins to alleviate pressure. It is possible that some of these major changes can cause a change in cell mechanics14.

The cellular mechanisms to maintain the OM of gram-negative bacteria still need to be studied. Lipid repair of the membrane has been identified in many bacteria, but it has never been visualized or delineated in bioaerosols. To visualize these phenotypic changes at the OM, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was utilized for high-resolution imaging due to its capability of clearly visualizing subcellular entities15,16. Previously Smith and King17, showed that aerosolization triggered antibiotic resistance response and increased expression of efflux pumps, an OM protein. It is clear there are many changes that occur at the cell’s OM when exposed to aerosolization stress. This current study was built upon previous research17 to visualize phenotypic changes in the nonpathogenic strain Escherichia coli MG1655 (genotype E. coli K-12, λ-, F-, rph-1) derived from parent strain W1485 by acridine orange curing of the F plasmid. This well-studied bacterium, sensitive to most commonly used antibiotics, was tested as the simulant for airborne pathogenic bacteria that were aerosolized for short-term (5 min) and long-term (30 min) durations. Briefly, in the previous study17, E. coli cells were aerosolized for six different time durations (0, 5, 10, 15, 30 and 45 min) and the collected aerosol sample was analyzed for antibiotic susceptibility and antibiotic-resistant gene upregulation. Two mechanisms were observed in the cells’ response to stress: (1) an immediate strong resistance to cell wall and protein synthesis inhibitors after 5 min of aerosolization, and (2) prolonged exposure (> 30 min) caused a second increase in antibiotic resistance accompanied by reduced culturability and extensive membrane damage, which the bacteria responded to by increasing lipid droplets synthesis to repair membrane lesions. This current study aims to further investigate the role of lipid droplets in the stress response and to compare electron microscopy data with the earlier gene upregulation findings for the same aerosolization periods.

Methods & materials

The acquisition of samples was completed using the same methods as described by Smith and King17.

Fresh Escherichia coli MG1655 cells (E. coli Genetic Resources at Yale CGSC, The Coli Genetic Stock Center, New Haven, NE, USA) were aerosolized for different time durations for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 45 min into a 27 L polypropylene and polyethylene (PP/PE) chamber equipped with a propeller to simulate ventilation airflow. Samples were collected using a wetted wall cyclone (WWC) bioaerosol collector operating at 100 L/min to collect particles into aqueous liquid (10% phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7.4) and concentrate them over a million times (from 1 L air into 1 µL liquid) while maintaining their culturability17,18,19. This study focused on the control sample (0 min), short-term (5 min), and long-term (30 min) aerosol samples. Both experimental samples showed an increase in antibiotic resistance.

Aerosolization and collection

In the experimental setup a 6-jet Collison nebulizer (BGI, Waltham, MA) was used for the aerosolization of fresh mid-log phase E. coli MG1655 cells. Cells were disseminated into the PP/PE temperature-humidity chamber using a 1” diameter vinyl tubing connected through a plastic hex adapter. After the cells were aerosolized for their respective time durations, they were collected by passing through a 1” diameter vinyl tubing connected to a 100 L/min WWC through another hex adapter.

A VOS 16 Propeller and Controller (VWR International, Radnor, PA) was inserted into the center of the chamber to maintain airflow at 80 L/min volumetric flow rate and 0.7 m/s velocity measured by hot wire anemometry (Model 8360, TSI Inc., Burnsville, MN). The chamber was sealed and kept airtight for the duration of testing in a BSL2 biosafety cabinet to ensure there was no contamination. Testing was conducted at room temperature. HOBO data logger (Onset, Bourne, MA) was placed into the chamber to collect real-time temperature and relative humidity data. All equipment was autoclaved or cleaned with 100% isopropanol and 5% bleach before each experiment. More details of the experimental setup and methodology can be found in the study conducted by Smith and King17 which was the preliminary work for this study.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) sample preparation

To concentrate E. coli cells to a target of 103 cells/mL, the collection of bioaerosols was completed 10 times at 100 L/min. The liquid suspensions collected after ten consecutive tests for each time period were pooled in the same 50 mL Nalgene tube. The cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 2880 g and 4 °C for 10 min and resuspended in 25 µL of Tris-HCL, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TE) buffer. Of the samples 5 µL were added to PELCO 300 mesh copper grids (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA) and then stained with 2% uranyl acetate for electron microscopy analysis.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging was carried out with a FEI TITAN® Themis STEM operating at 300 kV. The elemental composition of the sample was analyzed using the Electron Dispersive X-ray technique (EDX) with a high-efficiency Super X-ray Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) equipped on the electron microscope in the Materials Characterization Facility (MCF) at Texas A&M University. Multiple images were taken of each sample, and the best resolution was included.

Pressure analysis

After visualizing the phenotypic changes of the aerosolized cells in TEM, droplets of different diameters were detected on both sides of the cell membrane. Based on EDS analysis the composition of the droplets was identified as lipids and lipopolysaccharides. The pressure of each lipid droplet and the pressure of air affecting the cell membrane were calculated by accounting for the force using mass, m, and acceleration, a, and divided by the area, A (Table 1). Equation (1) was used for the pressure of the lipid droplets and Eq. (2) was used for the pressure of the airflow on the E. coli cells20.

The surface area, A, of the cell that experiences the pressure was used for the calculation of pressure on the cell. The weight of the lipid droplet was determined by first deriving the mass of the droplet-based on its volume calculated using the volumetric diameter and density, then multiplying the mass by the acceleration of the lipid droplet at the cell wall. The force of the air on the E. coli cell was calculated by multiplying the mass of the air derived from the density and the volume in the chamber by acceleration and divided by the surface area of the E. coli cell. The density was calculated considering the number of molecules and the mass arriving at Eq. 2. The dimensions of the lipid droplets and the cell were calculated using the ImageJ processing program to find the dimensions of the cell and lipid particles based on the scale with units in either µm or nm depending on the TEM image (ImageJ, NIH).

Gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from 500 µL of the E. coli cells of each sample (0 min, 5 min and 30 min samples of E. coli) using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), resuspended in 30 µL sterile RNase-free, 0.22 μm filter-sterilized deionized water and stored at −80°C until use. Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep with Ribo-Zero sequencing was conducted at the Texas A&M Institute for Genome Sciences & Society (TIGSS). Sequencing data was analyzed using BV-BRC HT-Seq and Tuxedo RNA analysis tools to gather differential expression results from 0 min, 5 min, and 30 min samples21. The upregulated genes and their functions in lipid synthesis are summarized in Supplementary Materials Table S1.

Results

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging

The results suggest that E. coli cells experience major damage and even lysis due to the environmental changes during aerosolization. Lipid droplets or lipoproteins were detected to plug the OM of E. coli to help it withstand increasing environmental stress. E. coli cells were analyzed with electron microscopy after 0 min, 5 min, and 30 min of aerosolization to delineate the progression of phenotypic changes after being exposed to airflow. TEM images show that the bacteria collected at 0 min, the stock solution without aerosolization, still maintain a round shape without signs of membrane damage. In the 5 min tests, different sizes of lipid droplets appear, seemingly to support and repair the membrane. After 30 min the cells’ membranes had mostly disintegrated. The cell still retaining its shape is covered with patches identified by EDS as proteins aggregated from the lysed cells and smaller cells that have leaked most of their contents. After analyzing the images, the pressure of the lipid droplets and the pressure of air affecting the membrane externally were determined using Eqs. 1 and 2.

Electron microscopy images indicate that some cells became damaged after 5 min of aerosolization. Figure 1 shows a clear difference in samples at different time steps from intact healthy cells in 0 min samples to cells with OM damage, elongation, and even disintegrated OM with cell lysis in some cases. The length: width ratio of whole cells (Fig. 1a, b, c) shows a 32% increase and an 84% increase for the change from the control to short-term, and control to long-term respectively. In the final time step, 30 min, there is clear cell damage with disintegration and protein aggregates. EDS analysis determined the composition of these aggregates to be proteins from lysed cells that clustered together in the hydrophilic environment. There was also a major decrease in culturability of cells aerosolized for longer periods, potentially due to the discontinuity of the OM. Control samples on average were ~ 4.0·106 CFU/mL. For the aerosol sample collections, the culturability was ~ 3.3·103 CFU/m3 and 200 CFU/m3for short-term and long-term aerosol samples, respectively17.

TEM images of samples after aerosolization of (a) 0 min, intact cells, surrounded by lipid membrane, (b) 5 min, an intact cell, showing thinner membrane area on the right side with lipid droplets inside, (c) 30 min, an elongated cell with a thin membrane surrounding it. Images taken at 5700x, 5700x, and 9800x magnification respectively, all showing a scale of 500 nm.

TEM images taken at 5700x magnitude showing lipid droplets repairing the membrane of samples after 5 min aerosolization. The movement of lipid particles is partly driven by buoyancy and partly by the pressure difference between the airflow and the cytoplasm due to the compromised membrane22. The lipid particles move to the damaged membrane to patch it in a way that could be similar to blood clotting where lipids also play an essential role in both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of prothrombin activation23. Red boxes show amplified images of two lipid droplets on the right near the top, crossing through the membrane, and at the bottom with magnitudes of 34000x and 27000x, respectively, repairing the OM of the cell; red arrows show other lipid droplets moving to the site of damage in the OM to patch the affected area.

TEM analysis shows that cellular entities seemingly traveled from inside of the cell to the OM to patch damage (Fig. 2). The role of lipid droplets in the Gram-negative bacteria, where they contribute to membrane repair and maintain the homeostasis of the cell envelope, can be analogized to the blood clotting process or coagulation that plays a crucial role in repairing blood vessels to prevent blood loss in vertebrates24. When the blood vessels become injured, the platelets or thrombocytes, which are small colorless cell fragments, initiate the clotting process by forming an initial plug at the injured site. This platelet plug is then stabilized by a fibrin network to form a clot. Interestingly, cholesterol type molecules are also synthesized in Gram-negative bacteria to provide increased tolerance to membrane trafficking processes such as lipid droplet accumulation, similarly to the role of cholesterol in animal cell membranes for increased structural rigidity25. Results also indicate that the stress of long-term aerosolization including the pressure changes and osmotic shock caused cell lysis (Fig. 3). To delineate and identify the cellular entities traveling within the cell to the OM, high-efficiency Super Energy Dispersive Spectrometry with Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDS/EDX) technique was used to analyze the chemical components of these entities at the OM. There was nearly twice the amount of oxygen in the EDS results indicating the potential presence of lipopolysaccharides (Supplementary Materials Table S2, Fig. S1, Fig. 4a, b). These droplets form round shapes with the hydrophobic portions of lipids inside the core. It is also more efficient and energetically favorable for these lipids to travel through the cell in a round shape and then plug the opening in the OM as shown in Fig. 2.

A previous study found a ~ 4.5-fold increase and a ~ 34-fold increase in expression of the rfaC gene which catalyzes lipopolysaccharide synthesis in samples that were aerosolized for 5 and 30 min respectively17. Some regions with lipids were not analyzed using EDS due to their small size. The typical spatial resolution of EM imaging is around 5–10 nm. When coupled with EDS, it detects X-ray photons generated by electron interaction with the sample, providing data from approximately 1 μm in diameter and 1 μm in depth. In heterogeneous samples, such as bacterial cytosol, other particles surrounding small droplets within the scattering volume can influence the EDS results. Figures 2 and 3 show several droplets with less than 10 nm in diameter in the theta shaped bacteria that has a size of about 1 μm × 2.5 μm. These droplets are too small to be effectively analyzed by the EDS/EDX method. Comparing the Carbon: Nitrogen: Oxygen ratios to identify lipids, the ratio of C: N associated with lipids is usually \(\:\ge\:\)6:126, while the EDS results showed a 10:1 ratio in the 5 min and 30 min samples (Fig. 4b, c), compared to the 2:1 ratio in the 0 min control sample (Fig. 4a). The increased presence of oxygen indicates that the particles could be LPS/LOS. Hydrogen is not represented in EDS results27,28. There is also a small trace of sulfur indicating the presence of amino acids in each sample29. Further study will be completed to identify the lipids as LD or LPS/LOS molecules.

Lipids and air pressure

The pressure of the surrounding air and the pressure of the lipid droplets activated to repair the OM have a balanced value. This finding indicates that the lipids are working to counter the pressure exerted on the cell by its external environment. The average pressure of the lipid droplets in the cell OM after 5 min of aerosolization was 2.32 × 10−2 N/m2 and the sum of pressure of the lipids in the cell OM was 6.96 × 10−2 N/m2, with a standard deviation of ± 1.18 × 10−5 N/m2. The external air pressure acting on the cell was 8.90 × 10−2 N/m2. All pressures were within the same magnitude and based on the calculations, the total pressure of the lipids at the membrane was approximately 80% of the air pressure exerted on the cell. These calculations very likely underestimate the pressure as they could only include lipids visibly repairing the cell at the time of imaging. Figure 2 also shows other lipids or lipoproteins moving toward the OM damage. Considering the standard deviation, the lipids that had not made it to the OM yet, and additional lipids (that may not have been large enough to visualize) that the cell was most likely sending for OM repair, the pressure of the lipids would amount to be closer to 100% of the air pressure. These calculations very likely underestimate the pressure as they do not include the small droplets.

The similarity of pressure of the lipids and air at the cell membrane is a new discovery and an area of research that should be built upon. While there is significant knowledge about lipid synthesis and OM repair, the biosynthesis of specific compounds for mechanisms in bacteria to mitigate environmental stressors is understudied.

Gene expression validation

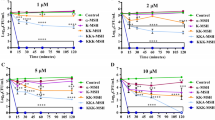

Figure 5a shows ARG related to lipid synthesis and efflux pump activity upregulated in 5 min samples and Fig. 5b shows the ARG’s upregulated in 30 min samples. These two categories of efflux pumps and lipids were chosen because of preliminary research and results showing upregulation of genes relating to efflux pump activity and lipopolysaccharide synthesis. Notably lipopolysaccharide synthesis expression was increasing in upregulation with the most resulting in the 30 min samples. Efflux pump activity consistently stayed elevated.

Interestingly nearly all the AMR genes related to efflux pumps showed overexpression either in the 5 min, 30 min samples, or both. On average a 41.95% increase of lppA, yhjD and by 30 min a dramatic six-fold (617.56%) increase was detected.

By 30 min the amount of lipid production changes dramatically, increasing lpxD by 125.3, aroC by 130.1%, lptB by 27.3, wecE by 32%, lptG by 23.5, lptE by 67%, and msbA with a percent increase of 21.5. Supplementary Materials Table S1 shows upregulated genes and their functions in E. coli MG 1655 lipid production.

Conclusions

In constant combat against antibiotic resistance, and with increasing evidence for its development due to environmental stress, it is important to gain as much information as possible on the coping mechanism of bacteria. This study is a first step in uncovering another potential way to target pathogenic bacteria. In the future, the findings of this study will be tested across different bacteria and different environmental conditions to offer further insight in the repair of the OM of gram-negative bacteria. Studies have shown that lipids and lipoproteins are essential in cell envelope repair, stress responses, and increased virulence of Gram-negative bacteria, lipid reordering, mobility, and bonding were modeled in cases of changing temperature, but pressure changes have not been extensively studied30,31.

TEM imaging showed the phenotypic changes of E. coli MG1655 before and after exposure to short-term aerosolization, 5 min, and long-term indoor aerosolization, 30 min, at airflow rates corresponding to the velocity of air that bacteria would become entrained in ventilated spaces. Short-term aerosolization samples exhibited major damage to the OM and elongation of the cells. Long-term aerosolization seemed to exhibit aggregates of cell material after lysis and elongated cells with a disintegrated OM leaving the cell susceptible to leakage and other, potentially fatal damages. After a closer look into the repairs the E. coli cells seemed to enact after short-term aerosolization, it was found that the repair molecules were most likely lipid droplets or lipoproteins and perfectly countered the air pressure impacting the E. coli cells from outside. Comparing current and earlier results, it appears that the cells are producing lipid droplets, specifically LPS/LOS, involving membrane openings for their transport to repair the OM damages that occurred during the stress of aerosolization17.

Genetic sequencing aligned with phenotypic changes and antibiotic resistance expression shows an increase in resistance to cell wall synthesis inhibitors, and increased repair of the cell membrane and efflux systems. Phenotypic imaging using TEM demonstrates a repair mechanism for the cell membrane. This research has provided a strong start to research showing the effects of aerosolization and the genotypic and phenotypic changes that have occurred due to aerosolization stress that triggers antibiotic resistance expression due to changes in the membrane17.

In summary, our results show that bacteria exposed to certain environmental conditions including increased pressure due to entrainment in ventilation airflow use lipid biosynthesis to counter the exact pressure to prevent the cells from lysis, leakage, or exposure to more toxins and thus becoming more susceptible to treatments. This is crucial information for the continued efforts in developing therapeutics and other forms of antimicrobials to slow the spread of antibiotic resistance in airborne bacteria.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

MacDermott-Opeskin, H. I., Gupta, V. & O’Mara, M. L. Lipid-mediated antimicrobial resistance: a Phantom menace or a new hope? Biophys. Rev. 14(1), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-021-00912-8 (2022).

Breijyeh, Z., Jubeh, B. & Karaman, R. Resistance of gram-negative bacteria to current antibacterial agents and approaches to resolve it. Molecules 25(6), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25061340 (2020).

Rollauer, S. E., Sooreshjani, M. A., Noinaj, N. & Buchanan, S. K. Outer membrane protein biogenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 370(1679), 20150023. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0023 (2015).

Ebbensgaard, A., Mordhorst, H., Aarestrup, F. M. & Hansen, E. B. The role of outer membrane proteins and lipopolysaccharides for the sensitivity of Escherichia coli to antimicrobial peptides. Front. Microbiol. 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02153 (2018).

Shrivastava, R., Jiang, X. & Chng, S. S. Outer membrane lipid homeostasis via retrograde phospholipid transport in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 106(3), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.13772 (2017).

May, K. L. & Grabowicz, M. The bacterial outer membrane is an evolving antibiotic barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115(36), 8852–8854. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812779115 (2018).

Bertani, B. & Ruiz, N. Function and Biogenesis of Lipopolysaccharides. 8. https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0001-2018 (2018).

Chi, X. et al. Lipid droplet is an ancient and inheritable organelle in Bacteria. bioRxiv. 2020.05.18.103093. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.18.103093 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Bacterial lipid droplets bind to DNA via an intermediary protein that enhances survival under stress. Nat. Commun. 8, 15979. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15979 (2017).

Sutterlin, H. A. et al. Disruption of lipid homeostasis in the Gram-negative cell envelope activates a novel cell death pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113(11), E1565-74. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601375113 (2016).

Okuda, S. et al. Cytoplasmic ATP hydrolysis powers transport of lipopolysaccharide across the periplasm in E. coli. Science 338, 1214–1217. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228984 (2012).

Piepenbreier, H., Diehl, A. & Fritz, G. Minimal exposure of lipid II cycle intermediates triggers cell wall antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 2733. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10673-4 (2019).

Huseby, D. L. et al. Antibiotic class with potent in vivo activity targeting lipopolysaccharide synthesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 121(15), e2317274121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2317274121 (2014). PMID: 38579010; PMCID: PMC11009625.

Smith, B. L. & King, M. D. Quiescence of Escherichia coli aerosols to survive mechanical stress during high-velocity collection. Microorganisms 11(3), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11030647 (2023).

Lam, J. et al. A universal approach to analyzing transmission electron microscopy with ImageJ. Cells 10(9), 2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092177 (2021).

Electron Microscopy: Transmission Electron Microscopy. Thermo Fisher Scientific - US. Retrieved from https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/electron-microscopy.html (n.d.)

Smith, B. L. & King, M. D. Aerosolization triggers immediate antibiotic resistance in bacteria. J. Aerosol. Sci. 164, 106017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2022.106017 (2022).

McFarland, A. R. et al. Wetted wall cyclones for bioaerosol sampling. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 44, 241–252 (2010).

King, M. D. & McFarland, A. R. Bioaerosol sampling with a wetted wall cyclone: cell culturability and DNA integrity of Escherichia coli bacteria. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 46, 82–93 (2012).

University of Tennessee Knoxville. Temperature and pressure. Retrieved June 2, 2023, from https://labs.phys.utk.edu/mbreinig/phys221core/modules/m9/temperature.html#:~:text=The%20pressure%20in%20a%20container,the%20pressure%20would%20be%20zero

Olson, R. D. et al. Nucleic acids research. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1003 (2022).

Bellotto, N. et al. Dependence of diffusion in Escherichia coli cytoplasm on protein size, environmental conditions, and cell growth. eLife 11. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.82654 (2022).

Marcus, A. J. The role of lipids in blood coagulation. In Advances in Lipid Research Vol. 4, 1–37 (eds Paoletti, R. & Kritchevsky, D.) (Elsevier, 1966). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4831-9940-5.50008-9

Chang, J. C. Hemostasis based on a novel ‘two-path unifying theory’ and classification of hemostatic disorders. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 29(7), 573–584 (2018).

Santoscoy, M. C. & Jarboe, L. R. Production of cholesterol-like molecules impacts Escherichia coli robustness, production capacity, and vesicle trafficking. Metab. Eng. 73, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2022.07.004 (2022). ISSN 1096–7176.

Feingold, K. R. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Bookshelf. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305896/

Lima-Faria, J. M. et al. Distribution and behavior of lipid droplets in hepatic cells analyzed by variations of cytochemical technique and scanning electron microscopy. MethodsX 9, 101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101769 (2022).

Heredia Rivera, B. & Gerardo Rodriguez, M. Characterization of airborne particles collected from car engine air filters using SEM and EDX techniques. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 13(10), 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13100985 (2016).

Brosnan, J. T. & Brosnan, M. E. The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview. J. Nutr. 136(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.6.1636s (2006).

Hews, C. L., Cho, T., Rowley, G. & Raivio, T. L. Maintaining integrity under stress: envelope stress response regulation of pathogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00313 (2019).

Pluhackova, K. & Horner, A. Native-like membrane models of E. coli polar lipid extract shed light on the importance of lipid composition complexity. BMC Biol. 19(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00936-8 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded, in part, by the grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF): CBET 2034048, the DHHS-NIH-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): 5R21AI169046-02, and the Hatch Program, United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA NIFA): TEX09746. The authors would like to thank Dr. Sisi Xiang at the Materials Characterization Facility at Texas A&M University for her great support with the electron microscopy analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BLS: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft; MZ: Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing; MDK: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition; Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, B.L., Zhang, M. & King, M.D. Airborne Escherichia coli bacteria biosynthesize lipids in response to aerosolization stress. Sci Rep 15, 2349 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86562-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86562-2