Abstract

The variability of East African short rains (October–December) has profound socioeconomic and environmental impacts on the region, making accurate seasonal rainfall predictions essential. We evaluated the predictability of East African short rains using model ensembles from the multi-system seasonal retrospective forecasts from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). We assess the prediction skill for 1- to 5-month lead times using forecasts initialized in September for each year from 1993 to 2016. Although most models exhibit significant mean rainfall biases, they generally show skill in predicting OND (October–December) precipitation anomalies across much of East Africa. However, skill is low or absent in some northern and western parts of the focus area. Along the East African coasts near Somalia and over parts of the western Indian Ocean, models demonstrate skill throughout the late winter (up to December–February), likely due to the persistence of sea surface temperature anomalies in the western Indian Ocean. Years when models consistently outperform persistence forecasts typically align with the mature phases of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and/or Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). This latter mode, when tracked using the Dipole Mode Index, is generally able to predict the sign of the rainfall anomaly in all models. Despite East Africa’s proximity to the west pole of the IOD, the correlation between short rains and IOD maximizes when both east and west are considered. This finding confirms previous studies based on observational datasets, which indicate that broader-scale IOD variability associated with changes in the Walker Circulation, rather than local SST fluctuations, is the primary driver behind East African rainfall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

East African region is exposed to climate variability such as recurrent drought and flood which cause to food insecurity. In recent years, intense droughts occurred in 1996, 1998, 2005, 2016, 2020 and 20211. For example, Click here to enter text. Confirmed the extended metrological drought from 2020 to 2021 caused much crop failure and livestock production in eastern Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. Since the region highly relies on rain-fed agriculture, the delayed onset or early cessation of the rainy seasons has a direct impact on crop pattern3. This region experiences two rather distinct wet seasons that are associated with the latitudinal migration of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ)4,5,6. The first wet season, known as the long rains, typically occurs during the boreal spring months of March to May (MAM), characterized by heavier and more prolonged rainfall. However, recent studies indicate that some countries, including Kenya and Uganda, have experienced rainfall in January and February, extending the wet season into these months7. The second wet season, or the short rains, generally takes place during the autumn months of October to December (OND), featuring shorter and less intense rainfall episodes5,8,9. Compared to the long rainy season, the short rains exhibit greater interannual variability, which has significant socioeconomic implications for the region10.

Previous studies11,12 assessed the predictability of the interannual variability of East African rains using both statistical and dynamical model outputs, as well as global observational datasets. For instance13, evaluate the predictability of East African short rains using operational seasonal forecasts of Greater Horn of Africa Climate Outlook Forum (GHACOF) model, which produced seasonal forecasts through a combination of dynamical and statistical climate models, expert judgment, and consensus-building, integrating global model outputs with regional climate knowledge and historical data. Their analysis revealed significant limitations, including low predictive skill and systematic errors, such as a pronounced dry bias in December over the southern parts of East Africa. In contrast14 identified a wet bias during the short rainy season across many parts of the region while evaluating ensemble climate forecasts from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts system-4 (ECMWF-4). Their analysis, employing metrics like the anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC), demonstrated that ECMWF-4 captured El Niño-Southern Osciallation (ENSO)-related anomalous years with region-dependent skill. Additionally11, explored the predictability of September–October–November (SON) rainfall anomaly using the Asia–Pacific Climate Center Ocean–Atmosphere coupled multi-model ensemble hindcasts initialized on August 1. They reported that 5 out of 10 coupled models showed statistically significant skill in predicting short rains over equatorial East Africa. However, skill was limited over most land areas, with better performance along sections of the western Indian Ocean coastline. Their findings also revealed a strong correlation between observed and predicted rainfall anomalies during SON, driven by the phase of a dominant regional climate mode, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)15.

ENSO and IOD mode have a strong influence on the interannual variability of east African short rains16,17, with their independent roles, as drivers of East African short rains, that have been studied using Scale Interaction Experiment-Frontier Research Center for Global Change, version 1 (SINTEX-F1) model10. The latter study found that the SON rainfall anomaly (RFa) exhibited significant correlation with the pure IOD (i.e., an IOD event occurring during neutral ENSO phases), while the correlation ENSO was found to be not statistically significant. When positive IOD coincided with strong El Nino in years like 1972 and 1997, East African short rains had experienced excess precipitation15. Yet, some studies18 suggest that positive ENSO phases, like the 2015 El Niño event, may occasionally exhibit a stronger association with East African short rains than the positive phase of the IOD. Consequently, a comprehensive assessment of East African rainfall predictability should account for the combined effects of ENSO and IOD on rainfall variability19 as has been done for other regions20.

To date, no study has assessed the predictability of East African short rains using the multi-system seasonal retrospective forecasts provided by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), which employs state-of-the-art seasonal prediction systems. This study aims to fill this gap by not only evaluating the predictive skill of these systems but also examining the models’ skill dependency on ENSO and IOD phases, considering both their independent and combined effects on the East African short rain patterns.

Model climatology and inter-annual variability

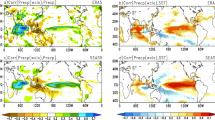

To characterize the mean bias in forecasting precipitation during East African short rain season, we compare rainfall climatology of each model (i.e., ensemble mean) with GPCP and ERA5 observational products (Fig. 1). Observational datasets and models present high precipitation over the southwest parts of the analyzed region. Specifically, the maximum rainfall pattern is observed over Congo Basin with secondary peaks over Lake Victoria and southern Ethiopia, all located inland and away from the coast. These high rainfall areas appear to be closely linked with orographic features, such as the Mitumba Mountains stretch along the Western Rift Valley in Eastern Congo and the East African highlands (e.g., Ethiopian, and Kenyan highlands). However, both GPCP and ERA5 have little precipitation over Indian Ocean with a relative maximum located between the Equator and 5°S. While models represent this feature, all but NCEP overestimate the rainfall pattern. Overall, the climatology depicted by observations and all models except NCEP present main features associated with orographic precipitation. However, a small-scale local precipitation maximum in the westernmost part of Ethiopia (i.e., the Ethiopian highlands, approximately around 7° N–38° E) is captured by only 50% of the models (i.e., JMA, ECMWF, CMCC, and MeteoF). While this feature is absent in the GPCP dataset (Fig. 1i), it appears to be realistic as it is also evident in ERA5 (Fig. 1j), which provides precipitation estimates at a higher spatial resolution (0.25° for ERA5 vs. 0.5° for GPCP). As expected, compared to observational datasets, the models’ climatology generally exhibits smoother precipitation patterns.

The upper panel shows the rainfall climatology during the short rains (October-December: OND) derived from GPCP (i), ERA5 (j), and the seasonal prediction systems from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), which includes 8 ocean–atmosphere coupled model ensembles and cover the period 1993–2016 (a–h). The lower panel shows area-averaged OND rainfall anomalies for part of Eastern Africa (30–50° E, 5°S–10° N; blue dashed box in i) for models, ERA5, and GPCP dataset. Anomalies are computed relative to the climatology shown in the upper panel. All maps and time series plots were created using Python 3.12.3 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3123/), utilizing libraries such as NumPy, Matplotlib, Cmaps, and Cartopy.

We also examined the year-to-year variation of short rainy season (Fig. 1k) by averaging RFa over part of East Africa between 5° S and 10° N and 30°–50° E (blue box in Fig. 1ai). Subsequently, we derived an equatorial East African rainfall index (EEARi), following a methodology5. The index reveals that 1997 appears to represent the peak rainfall for both models and observation. However, it also indicates that some models such as DWD and NCEP significantly underestimate this event. GPCP and ERA5 generally presents more year-to-year variations than the models as the ensemble means smooth out most of the internal variability that grows from the perturbation in the initial conditions. Both models and observations generally exhibit consistency during years with relatively strong positive rainfall anomalies. This consistency also holds true for a few negative events presented in 1996 and 2010.

In addition to the evolution of the EEARi, we looked at the spatial pattern of rainfall variability during OND season as represented by the inter-annual standard deviation for both models and observational dataset (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information). Over the ocean, GPCP and ERA5 present a double maximum variability at both side of the equator at +− 5°, while in the model this is true only for ECCC MeteoF and NCEP. Furthermore, several models but especially JMA and UKMO presents a significant bias in OND variability over Eastern Indian Ocean. This high rainfall variability also shown over East African highlands and near to Congo basin. Consistent with the GPCP and ERA5 climatology, some models, including JMA, CMCC, and NCEP, demonstrate high rainfall variability over the highlands (Fig. S1a, e and g), while all models show minimal variability over northern parts of East Africa.

Predictive skill

The predictive skills of coupled models for East African short rains are assessed using spatial (i.e., timeseries of pattern correlation) and temporal (i.e., pointwise-correlation map) anomaly correlation coefficient. The ACC analysis is a common statistical metric widely used to measure the spatial (or temporal) correlation between the simulated and the observed anomaly each computed relative to their respective climatology (see methods)21,22.

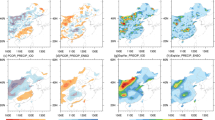

We perform the correlation analysis between ensemble means of each model and the observed East African rainfall anomalies at three lead seasons: Lead season 1 corresponds to the first forecast period (OND), lead season 2 to the second period (NDJ), and lead season 3 to the third period (DJF). All forecasts are initialized in September for each year from 1993 to 2016. At lead season 1, nearly all coupled models exhibit a significant correlation exceeding 0.6 across the western tropical Indian Ocean and the central to eastern African coastal regions. Moreover, along the East African coasts, models such as JMA, ECMWF, ECCC, UKMO, and CMCC (shown in Fig. 2a–e) demonstrate robust predictive capabilities extending generally up to lead season 2. In some places, such as the Equatorial Indian Ocean region within the studied domain, this skill persists up to lead season 3, probably associated with long persistence in SST, which present autocorrelation values often higher than 0.85 up to lead season 3 (Fig. S2 in the Supporting Information). However, the DWD and NCEP models exhibited poor predictive skill, presenting correlations below 0.2 across several parts of the region in East Africa. Overall, the forecasts demonstrate weak correlation with both GPCP and ERA5, fail to predict rainfall patterns across Northern, Western, and many highland regions throughout all lead seasons.

Pointwise-correlation maps between GPCP and C3S model predictions for lead season 1 (October–December: OND), lead season 2 (November–January: NDJ), and lead season 3 (December–February: DJF) of rainfall anomalies (ensemble mean) during 1993–2016. Stippling indicates area where the correlation between the hindcast and observation are statistically significant at 90% confidence level, as calculated by a two-side Student t-test for 22(N-2) degrees of freedom. The maps were created using Python 3.12.3 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3123/), utilizing libraries such as NumPy, Matplotlib, Cmaps, and Cartopy.

Furthermore, we also looked at the dependency of the prediction skill on monthly lead-time computing from ACC for patterns of anomalous precipitation. To understand the predictive skills of each model at specific year, we highlighted the 3 most skillful years in which the models consistently outperform the persistence forecasts for lead time from 1 to 3 months (Fig. 3a–h). Specifically, when compared to persistence forecasts, all models except DWD model present skillful predictions for the year 1997 at 1–3 lead months. Similarly, the year 2010 was identified as the most successfully predicted year in models such as JMA (Fig. 3a) and ranked as the third most skillful year in models such as UKMO, NCEP, and MeteoF (Fig. 3d, f, and g), with ACC values greater than the persistence forecast up to the third lead month. Notably, DWD is the only model that successfully capture years such as 2015, 2009, and 1994, which are missed by other models (Fig. 3h). Generally, as lead time increases, the forecasting skill of models tends to decline with most years exhibiting significantly lower ACC values compared to the persistent skill level. Overall, precipitation anomalies in years 1997 and 2010 are more predictable, with most of the models presenting ACC values that outperform the persistence skill through November (Fig. 3a–h). To assess the interannual predictive skill of models for the East African short rainy season, we looked at the correlation between the observed and predicted RFa (computed over EEAR box) across the hindcast periods (Fig. 3i). The highest skill presented in all models for the year 1997. Moreover, the skills of most models are similar during years 1994, 2008 and 2010 (Fig. 3i). Particularly, 1994 is the second-most skillful year after 1997, with higher ACC values evident in models such as ECMWF, CMCC, UKMO, and DWD. Similarly, in the year 2008, we observe high correlation values across most coupled models, except for the ECCC and MeteoF. Several years with improved predictive accuracy seem to align with ENSO and IOD events, highlighting the significant impact these climate patterns have on both the variability and predictability of East African rainfall.

The upper panel shows the anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC) between GPCP and each C3S model (a–h) for monthly rainfall anomaly over part of Eastern Africa (blue dashed box of Fig. 1i) for each year (grey lines) from lead month 0 (September) to lead month 5 (February). In each subfigure, the top three forecasts stand out with distinct colours: the most accurate year is highlighted in red, the second-best in blue, and the third best in magenta. These forecasts are determined by sorting all predicted years based on their average ACC values across September and October. The black dashed line indicates the persistence forecast. The lower panel (i) illustrates the spatial correlation between each model and GPCP rainfall anomaly patterns for the OND seasonal mean, calculated over Equatorial Eastern Africa (30–50° E, 5°S–10° N).

Predictability conditional on ENSO and IOD phases

Several studies have shown how modes of interannual variability in the Indian and Pacific tropical oceans represent a main source of predictability for seasonal rainfall patterns23,24. These studies indicate a clear association between mature phases of IOD and ENSO events10,15. Thus, we investigate the role of tropical SST in influencing variability in East African short rains, utilizing indices that monitor rainfall (i.e., EEARi), ENSO and IOD. Specifically, the Niño 3.4 index (N3.4; SST anomalies averaged over 120° W–170° W, 5°S–5° N) tracks ENSO, while the Dipole Mode Index (DMI; SST anomalies difference between the western Indian Ocean (DMIw), 50° E–70° E, 10°S–10° N, and eastern Indian Ocean (DMIe), 90–110° E, 10°S -0) monitors IOD variability15,20. The relationship between EEARi, N3.4, and DMI across models (Fig. 4a–h) and ERA5 (Fig. 4i) indicate that negative (positive) RFa are consistently linked to the concurrent negative (positive) phases of IOD and ENSO, with the magnitude of the anomaly that depends on the intensity of these two drivers in various years. ENSO and IOD a present an important co-variability that result in a significant N3.4-DMI correlation during the OND season in both observations and models (0.74 for the observation and between 0.65 and 0.78 for the models; Fig. 4).

Scatterplot of Niño3.4 index (N34; x-axis) versus Dipole Mode Index (DMI; y-axis) during OND season for each of the 24 years analyzed in both model predictions (a–h) and GPCP dataset (i). The area of the circle is proportional to the absolute value of OND rainfall anomaly averaged over part of the Eastern Africa (blue dashed box of Fig. 1i), with positive (negative) anomaly coloured in green (orange). As in Fig. 3 the best forecasted year is highlighted in red, the second-best in blue, and the third best in magenta. Additionally, the correlation coefficient between N3.4 and DMI is provided a top each subfigure for reference. (j–r) shows a similar analysis but with the western pole of the DMI index (DMIw).

When both IOD and ENSO are in the positive phase, all coupled models and GPCP present above-normal OND rainfall (green colors on Fig. 4) across the East African region. The best predicted year (Fig. 3) is associated with the strongest El Niño event on record (1997/1998), which co-occurred with strong positive IOD phase. During the short rainy season of 1997, East Africa experienced the largest positive RFa, reaching up to 3 mm/day (Figs. 1k and 4). While all models represent a high correlation between ENSO and IOD, the observed extreme 1997 precipitation event is particularly evident only in six out of eight models (i.e., JMA, ECMWF, ECCC, UKMO, CMCC and NCEP). In this year, however only DWD model fail to simulate this RFa event, despite the high correlation between DMI and N34 is presented (Fig. 4h).

On the other hand, during negative ENSO and IOD phases, all models and GPCP tend to exhibit negative OND RFa (as shown by the yellow-filled circles in Fig. 4). For instance, during the 1998 negative ENSO and IOD phase (Fall 1998) that immediately followed the record-breaking 1997/1998 El Niño event, the observed negative RFa were successfully forecasted at lead months in only three models such as UKMO, MeteoF and NCEP (Fig. 3d, f, and g). However, when lead season considered only MeteoF, ECMWF, and JMA can predicted an amplitude of the OND anomaly comparable to the observation (Fig. 3i). Additionally, 2010 is identified as the second most skillfully year by JMA (Fig. 3a), and as third most skillfully year by UKMO, MeteoF, and NCEP models (Fig. 3d, f, and g), showing negative OND seasonal anomalies during negative phases of DMI and N34 (Fig. 4a, f, and g).

Given the vicinity of East Africa to the Western pole of the IOD (i.e., DMIw region), we wanted to explore if the interannual variability of East African short rain was more strongly connected to fluctuations in the DMIw index, which has been shown to exhibit slightly higher predictability11. However, despite this geographical closeness, the correlation between OND RFa in the EEAR region (i.e., EEARi) and DMIw is slightly lower than the correlation between EEARi and the overall DMI (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information). This finding is remarkable considering that ENSO present a stronger connection with the DMIw compared to the DMI, as evidenced in both observational data and climate models (Fig. 4j–r). The stronger correlation between EEARi and the DMI, despite the expectation that local SST variations would play a more significant role, emphasizes the importance of broader-scale IOD variability. This suggests that the key factor influencing East African rainfall is the IOD-driven disruption of the zonal atmospheric circulation associated with the Indian Ocean branch of the Walker Circulation.

Discussion

We assessed the predictability of East African short rains in all eight seasonal retrospective forecast systems from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). Given our aim, we only consider the forecast initialized at the beginning of the short rainy season, namely in September.

Despite sizable local biases (Fig. 1), most models appear to have skill in predicting OND precipitation anomalies over most parts of East Africa, and present low or no skill in some areas of northern and western Africa. Along the East African coasts (near Somalia) and some portions of western Indian ocean, models have skill up to DJF seasons, as shown by the stippling indicating significant correlations (Fig. 2). This is probably associated with the SST persistence in western Indian Ocean (Fig. S2 in the Supporting Information) which tend to be significant up to winter season in most models. These results are in line with previous studies that have analyzed the SINTEX-F1 model10 and the APCC Ocean–Atmosphere coupled multi-model ensemble11.

It is noteworthy that these results (referring to Fig. 2) are rather robust and do not change significantly using a different verification dataset such as ERA5 reanalysis (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Information). In all models the skill has a strong inter-annual dependency that is evident when looking at the monthly ACC for the first 6-month lead-time (Fig. 3). However, differently from the pointwise correlation maps, this ACC skill might vary if one considers a different verification dataset. Specifically, 2010 is identified as the second most skillful year only when we evaluate against ERA5 reanalysis (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Information).

Given then strong influence that major tropical modes have in the region25,26,27, it does not surprise that skillful years are usually associated with ENSO and IOD mature phases, with the largest anomaly occurring during years of contemporary ENSO and IOD extremes. Moreover, recent studies by28,29 have shown, using observational and reanalysis products—including GPCP and ERA5, as used in this study—that knowledge of ENSO and IOD phases alone can be exploited to provide skillful outlook for the OND rainy season up to a full season in advance, specifically starting from July–August–September (JAS). Given simplicity and effectiveness of the compositing approach used by28,29, future evaluations of advanced statistical and dynamical model predictions could consider this approach as an alternative to the persistence forecast generally used as a reference.

While the largest precipitation events seem to occur during El Niño years, the correlation between the RFa and DMI, in both models and observations, is substantially larger than the correlation between RFa and N3.4, indicating that the Indian Ocean SST response to ENSO plays a more important role than the direct ENSO-driver remote impact (e.g., atmospheric bridge) on the regional rainfall. Consistent with this, the sign of DMI can almost always predict the sign of the short rain seasonal anomaly, which is not always the case for the sign of the N3.4. As observed in previous studies, the east–west dipole in SST anomalies, combined with an unusual atmospheric zonal circulation pattern, serves as a reliable driver for the variability of short rains in East Africa1,30.

Considering that the predictability of East African short rains is often linked to the co-variability of ENSO and IOD (Table. S1), it is surprising that during the 2015/2016 period—one of the strongest El Niño events on record—almost all models failed to replicate the OND rainfall patterns, except for the DWD model (see Fig. 3h). This can be attributed to a relatively weak positive phase of the IOD in 2015/2016 compared to the 1997/1998 El Niño events, which in turn led to a reduction in the intensity of the Indian Ocean Walker-type circulations18.

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of East African short rains predictability using state-of-the-art seasonal forecast systems, focusing on the interplay between ENSO and IOD phases. By demonstrating the critical role of large-scale climate modes and their combined influence on rainfall variability, our findings contribute to advancing the understanding of seasonal climate predictability in the region crucial for improving forecast systems.

Datasets, model, and methods

Observational datasets

We utilize observed rainfall data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) version 3.2 and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) fifth-generation reanalysis (ERA5). The GPCP version 3.2 provide estimates with a resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° from 1979 to the present31,32. The dataset contains monthly analyses of global precipitation, merging observations from rain gauges with precipitation estimates from low-orbit satellite microwave data, geosynchronous-orbit satellite infrared data, sounder-based estimates. The ERA5 dataset, provides global climate reanalysis data with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. It integrates observational data from various sources, including surface stations, upper-air observations, and satellite data, using data assimilation. ERA5 offers monthly mean fields for multiple variables, including precipitation and sea surface temperature, spanning from 1979 to the present study33.

Each datasets offers distinct advantages: GPCP assimilate precipitation data from multiple sources, and ERA5 provides a higher-resolution precipitation field that is physically consistent with the SST field used in this study.

Seasonal retrospective forecasts from C3S

To assess the predictability of the East African short rain, we conducted an evaluation of eight coupled ocean–atmosphere model seasonal prediction systems available from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) offers a comprehensive multi-system seasonal forecast service, presenting data from various state-of-the-art seasonal prediction systems. These systems offer insights into future climate patterns up to 6 months in advance. The service includes aggregated forecasts from multiple systems, as well as detailed information from individual participating centers, such as ECMWF, Met Office, Météo-France, Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD), Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change (CMCC), National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Table 1 provides a detailed summary of all models, highlighting differences in resolution, ensemble sizes. Climate variables, including precipitation and SST were retrieved for a common hindcast period spanning from 1993 to 2016, at a monthly time scale.

Spatial and temporal anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC)

To evaluate the models’ skill in forecasting East African precipitation across both spatial and temporal dimensions, we conducted an ACC analysis. ACC is not only a powerful yet simple metric but also a standard tool in climate predictability studies. Its well-established and widely recognized use ensures comparability with previous research while facilitating interpretation by the broader scientific community. We use ACC as a statistical measure to assess the spatial or temporal correlation between the simulated and observed anomalies, relative to their individual climatological references. Mathematically, it can be expressed by the following equation:

where, in the case of temporal ACC, Obi is observational data for each year, Fci is ensemble mean forecast anomaly at initialized time for each year, n is numbers of years, \(\overline{Fc}\text{ and }\) \(\overline{Ob }\) are the time mean of models’ ensembles and observation, respectively. Before performing the spatial correlation, both SST and precipitation datasets are bilinearly interpolated to a common grid of resolution of 1° × 1°.

Data availability

The seasonal forecasts analyzed in this study are available on the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store portal at https://climate.copernicus.eu/seasonal-forecasts. To access the data, please consult the "Seasonal forecast monthly statistics on single levels" catalog. Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) rainfall data at monthly mean frequency was obtained from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/global-precipitation-climatology-project. ERA5 monthly mean rainfall and sea surface temperature was downloaded from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) at Climate Data Store at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels-monthly-means?tab=form. The code used for the analyses is publicly accessible on Zenodo.org: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14616478.

Code availability

All analyses and figures were performed and displayed using Python 3.12.3 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3123/), utilizing libraries such as NumPy, Matplotlib, Cmaps, and Cartopy. The code used for these analyses is publicly accessible on Zenodo.org: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14616478.

References

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. On the predictability of the extreme drought in East Africa during the short rains season. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl100905 (2022).

Amha, Y. et al. Unrelenting catastrophic droughts and successive failed rainy seasons in the greater horn of Africa what can we do better to protect millions of smallholder farmers and livestock keepers from extreme weather and climate crisis? (2023).

MacLeod, D. Seasonal forecasts of the East African long rains: Insight from atmospheric relaxation experiments. Clim. Dyn. 53, 4505–4520 (2019).

Camberlin, P. & Philippon, N. The East African March–May rainy season: Associated atmospheric dynamics and predictability over the 1968–97 period. J. Clim. 15(9), 1002–1019 (2002).

Palmer, et al. Drivers and impacts of Eastern African rainfall variability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00397-x (2023).

Kebacho, L. L. & Chen, H. The dominant modes of the long rains interannual variability over Tanzania and their oceanic drivers. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 5273–5292 (2022).

Kebacho, L. L. Climatological characteristics and interannual variability of the leading mode of eastern African precipitation in January and February. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 1371–1390 (2024).

Nicholson, S. E. Climate and climatic variability of rainfall over eastern Africa. Rev. Geophys. 55, 590–635 (2017).

Gamoyo, M., Reason, C. & Obura, D. Rainfall variability over the East African coast. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 120, 311–322 (2015).

Behera, S. K. et al. Paramount impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the East African short rains: A CGCM study. J. Clim. 18(21), 4514–4530 (2005).

Bahaga, T. K., Kucharski, F., Tsidu, G. M. & Yang, H. Assessment of prediction and predictability of short rains over equatorial East Africa using a multi-model ensemble. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 123, 637–649 (2016).

Oelfke, C., And, C., Webster, P. J. & Cole, J. E. Interdecadal variability of the relationship between the Indian Ocean Zonal Mode and East African Coastal rainfall anomalies (2003).

Walker, D. P. et al. Skill of dynamical and GHACOF consensus seasonal forecasts of East African rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 53, 4911–4935 (2019).

Ogutu, G. E. O., Franssen, W. H. P., Supit, I., Omondi, P. & Hutjes, R. W. A. Skill of ECMWF system-4 ensemble seasonal climate forecasts for East Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 2734–2756 (2017).

Saji, N., Goswami, B., Vinayachandran, P. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Lett. Nat. 401, 360–363 (1999).

Endris, H. S. et al. Future changes in rainfall associated with ENSO, IOD and changes in the mean state over Eastern Africa. Clim. Dyn. 52, 2029–2053 (2019).

Indeje, M., Semazzi, F. H. M. & Ogallo, L. J. ENSO signals in East African rainfall seasons. Int. J. Climatol. 20, 19–46 (2000).

Macleod, D. & Caminade, C. The moderate impact of the 2015 El Niño over East Africa and its representation in seasonal reforecasts. (2019) https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19.

Cherchi, A. & Navarra, A. Influence of ENSO and of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Indian summer monsoon variability. Clim. Dyn. 41, 81–103 (2013).

Liguori, G., McGregor, S., Singh, M., Arblaster, J. & Di Lorenzo, E. Revisiting ENSO and IOD contributions to Australian precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL094295 (2022).

Nicolì, D. et al. The Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC) decadal prediction system. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 179–197 (2023).

Wilks, D. Series editors. In Statistical methods in the atmospheric sciences ii (Academic Press, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-385022-5.00022-1.

Palmer, T. N. & Anderson, D. L. T. The prospects for seasonal forecasting—A review paper. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 120, 755–793 (1994).

Troccoli, A. Seasonal climate forecasting. Meteorol. Appl. 17, 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/met.184 (2010).

Hastenrath, S., Nicklis, A. & Greischar, L. Atmospheric-hydrospheric mechanisms of climate anomalies in the western equatorial Indian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 20219–20235 (1993).

Behera, S. K. et al. Paramount impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the East African short rains: A CGCM study. J. Clim. 18, 4514–4530 (2005).

Wang, H., Kumar, A., Murtugudde, R., Narapusetty, B. & Seip, K. L. Covariations between the Indian Ocean dipole and ENSO: A modeling study. Clim. Dyn. 53, 5743–5761 (2019).

Roy, I., Mliwa, M. & Troccoli, A. Important drivers of East African monsoon variability and improving rainy season onset prediction. Nat. Hazards 120, 429–445 (2024).

Roy, I. & Troccoli, A. Identifying important drivers of East African October to December rainfall season. Sci. Total Environ. 914, 169615 (2024).

Black, E., Slingo, J. & Sperber, K. R. An observational study of the relationship between excessively strong short rains in coastal East Africa and Indian Ocean SST.

Adler, R. F. et al. The Version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Precipitation Analysis (1979-Present). http://precip.gsfc.nasa.gov (2003).

Huffman, G. J. et al. The new version 3.2 global precipitation climatology project (GPCP) monthly and daily precipitation products. J. Clim. 36, 7635–7655 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Gualdi, S. et al. The new CMCC Operational Seasonal Prediction System Issue TN0288 CMCC Technical Notes. (2020) https://doi.org/10.25424/CMCC/SPS3.5.

Stevens, B. et al. Atmospheric component of the MPI-M earth system model: ECHAM6. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 5, 146–172 (2013).

Merryfield, W. J. et al. The canadian seasonal to interannual prediction system. Part I: Models and initialization. Mon. Weather Rev. 141, 2910–2945 (2013).

Johnson, S. J. et al. SEAS5: The new ECMWF seasonal forecast system. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1087–1117 (2019).

Hitoshi, Y. et al. Upgrade of JMA’s Operational Global Model. http://oceans11.lanl.gov/trac/CICE. (2020).

Lauriane Baté Laurent Dorec, C. A. J.-F. G. Documentaton of the METEO-FRANCE Seasonal Forecastng System 8 Officiac Reference Nueber Service Contract: 2018/C3S_330_Météo-France/SC1 ECMWF COPERNICUS REPORT (2021).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J. Clim. 27, 2185–2208 (2014).

Williams, K. D. et al. The met office global coupled model 3.0 and 3.1 (GC3.0 and GC3.1) configurations. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 10, 357–380 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the modeling teams contributing to the C3S Copernicus seasonal retrospective forecasts, whose model outputs have been instrumental in this study. For access to the data, kindly consult the “Seasonal forecast monthly statistics on single levels” catalogue available on the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store portal at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. and G.L. conceived the study. and A.K.T. analysed the results and produced all the figures. A.K.T., and G.L. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors contributed to the development of ideas, writing and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tefera, A.K., Liguori, G., Cabos, W. et al. Seasonal forecasting of East African short rains. Sci Rep 15, 2467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86564-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86564-0