Abstract

To investigate the dynamic characteristics and safe operation speed threshold of metro train passing through curved bridge (CB) considering resilient wheels, the mechanical connection characteristics of rim and web are discussed firstly. Based on the train–track–bridge interaction theory, the coupled dynamic model of metro train-CB considering resilient wheels is established. Then, the vehicle–bridge coupled dynamic characteristics under the excitation of long-short wave track irregularity are researched. Finally, from the perspective of dynamics, the safe operating speed threshold of metro trains passing through curved bridge considering resilient wheels (RW) is discussed. Results show that the vertical wheel–rail force of RW is reduced, but the lateral wheel–rail force is amplified compared with the solid wheels (SW). The vertical vibration acceleration of the wheel is reduced, but the lateral vibration acceleration is increased. It is recommended that the speed of metro trains running on curved bridge is not more than 60 km/h. The vehicle–bridge coupling dynamic response is aggravated with the speed and load of metro train. The vibration of the inner side of the curved bridge is greater than that of the outer side, and the vibration reduction effect of the RW on the inner side is more significant than that on the outer side. The RW has a vibration absorption effect on the wheel–rail vertical and the vibration of the curved bridge force within 40–140 Hz.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metro train is an economical and fast mode of transportation, which accounts for the highest proportion in urban rail transit. However, with the expansion of metro train lines, the proportion of viaducts is also increasing sharply, the vehicle–bridge coupled vibration problem can have a negative impact on passenger comfort and the living environment of residents along the line1. In order to improve the utilization rate of urban space, curve bridges have been widely used in urban rail transit because of their strong terrain adaptability2. The vibration of bridge structure is induced when the metro train running the elevated curved bridge, and the vibration of the curved bridge is transmitted to the metro train through the track system, the vibration of the metro train is intensified, the vehicle–bridge coupled vibration is formed3. The train–bridge interaction of metro train running on curved bridge is more complex than that on straight bridges. For instance, greater wheel–rail contact stress, wheel–rail dynamic response, rail corrugation and curve squeal are generated4,5,6,7. Residents near the metro train line will be disturbed by whole-body vibration and low-frequency noise, and the performance of precision instruments and the stability of ancient buildings may also be affected8. Moreover, because the characteristics of high mass center, strong inertia and long car body of the metro train, the vibration of the curved bridge is further aggravated at the action of centrifugal force when the metro train running on the curved bridge9. The safety, stability and comfort of metro train passing through the bridge are reduced through severe vibration, the service state and durability of the curved bridge are also affected, and even the risk of train derailment is induced10. Thus, the metro train-CB coupled vibration is particularly necessary to be discussed and suppressed.

In the process of studying the traditional vehicle–bridge coupled vibration problem, the influence of bridge curvature is usually ignored and the mechanical model of the curved bridge is simplified into a straight bridge, which may lead to significant deviation in the study of the dynamic response of the train–bridge coupled system. Therefore, a reasonable and accurate mechanical model of curved bridge is urgently established. For the mechanical model of curved bridge, numerical analysis method and finite element method are generally used. Such as, Zhai11 improved semi-analytical approach for the vibrations of a Timoshenko curved beam is newly proposed based on the Chebyshev-tau method. The train–track–curve bridge coupled dynamics is established, and the accuracy and reliability of the scheme are verified, which shows that the coupled vibration response of the train is significantly different from that of the curved bridge and the traditional linear bridge, respectively. Virajan and Zeng et al.2,9 used the thin-walled box girder finite element method to numerically simulate a curved box girder bridge, which considers the degrees of freedom such as torsional warpage, deformation, and distortion warpage, and studies the response of different bridge lengths, speeds, and track irregularities to the bridge. Elias1 proposed the interaction in the radial and torsional directions of curved bridge, indicating that the lateral dynamic response of the vehicle–bridge coupled system is controlled by the centrifugal force generated by the curved bridge track when the curvature or speed is large. To ensure the simulation accuracy and improve the computational efficiency. In this paper, the finite element method is used to establish the mechanical model of the curved bridge, and the dynamic characteristics of metro train-CB coupled system are investigated.

As one of the vibration reduction measures of rail transit, the RW is embedded with rubber between the rim and the web. Relying on the characteristics of vibration reduction and vibration isolation of rubber, the wheel–rail interaction force is reduced. At present, it is widely used in rail transit systems such as trams with small and medium traffic volume, low speed, and small axle load at home and abroad12,13. Since the history of metro trains development in other countries is longer than that in China, other countries pay more attention to the environment and comfort, and have used RW on metro trains for a long time. At present, RW are basically used on pure ground lines or underground and ground mixed urban rail lines, there are also quite a few RW used on completely underground urban rail lines, such as the Madrid Metro in Spain and the Monterrey Metro in Mexico14,15. When metro train passes through curved bridge, the lateral wheel–rail force is intensified by the centrifugal force. The metro train with RW may induce the threat of wheelset derailment. Furthermore, the structure of RW is more complex than that of traditional SW, and the dynamic characteristics are aggravated. The development of RW is limited by metro trains with high speed and large traffic volume. The coupled dynamic characteristics of metro train-CB with RW under the action of inertial force are not distinct. and the safety of metro train passing through curve bridge considering RW should be paid more attention. Therefore, it is urgent to carry out research on the coupled vibration characteristics and operational safety speed thresholds of metro train-CB with RW.

The RW has three structural forms, such as shear type, compression type, and compression–shear composite type16. Thompson17 found that when the compression elastic wheel bears a large lateral force during driving, the compression RW dissatisfies the mechanical requirements of the wheel. Therefore, an improved Bochum54 RW is proposed. Remington18 studied the mechanical properties of the rubber layer of the shear RW under the action of wheel–rail force. Since the compression–shear composite RW is mainly subjected to vertical pressure and shear bidirectional load, its rubber shape is V-shaped or W-shaped, and the radial stiffness and axial stiffness of the RW are controlled by the angle between the V-shaped or W-shaped. Therefore, the compression–shear composite RW is the mainstream development trend in small and medium-sized urban rail transit19.

To study the compatibility of RW in rail vehicles, multi-rigid-body dynamics is used to establish a metro train with RW. It is the current research trend to explore the dynamic characteristics and performance of RW in rail vehicles. Such as, Wen20 used the multi-body dynamics software SIMPACK to establish two models of the traditional model of the RW and the composite model of the RW, and studied the basic dynamic indexes such as the stability, stability and curve passing performance of the rail vehicle considering the RW. Hu XT21 simulated the rubber of RW through one, four, and 20 uniform circumferential distribution force element. Tram dynamics models with RW are established, and the performance indexes of trams are studied. The tram with 20 uniformly distributed force units simulating RW rubber has better running stability. Zhou22 regarded the rubber of the RW as spatial stiffness-damping element, so that the rim and the web have relative motion. Results show that compared with the traditional rigid wheel, the vibration of the web is significantly reduced in the medium and high frequency, the radial stiffness and axial stiffness of the RW are also proposed. On this basis, Xiao23 studied the dynamic response of the RW installed on the intercity train at the rail weld, and introduced the mass factor to analyze the influence of the rubber position on the rim acceleration and wheel–rail impact force. Tian24 found that compared with the rigid wheel, the RW can effectively suppress the vibration of the rim, tread, and web under the vertical excitation of the wheel–rail, and the vibration acceleration of the web is the most significant. Tian25 studied the influence of resilient wheelset wheel polygon effect on the stability and safety of vehicle operation. Results show that the resilient wheelset can effectively reduce the wheel–rail vertical force and restrain the wheel polygon. After 30 Hz, the inhibition effect of resilient wheelset polygon is more and more significant. Chen26,27 established a coupled dynamic model of the metro train-LSCSB (long span cable-stayed bridge) system with RW, studied the influence of RW on the dynamic characteristics of the metro train-LSCSB system, and optimized the stiffness and damping of the RW. The results show that the elastic wheel can reduce the lateral vibration of LSCSB in the range of 2 ~ 20 Hz. Holger28 studied the influence of the stiffness and damping of the RW on the vibration characteristics and stability of the subway. Kouroussis29 established a vehicle–track–soil composite model to study the mitigation effect of RW on railway ground vibration, indicating that vehicle dynamics has a certain influence on the occurrence of soil vibration waves. Therefore, the rubber of RW is usually regarded as spatial stiffness-damping to study the dynamic characteristics of the rail vehicle is the current trend.

However, few scholars have considered RW in metro train. The vibration reduction effect and compatibility of the subway train considering the RW on the curved bridge are studied. In addition, to further ensure the safety of metro trains with RW passing through small curve radius bridges, it is particularly important to limit the running speed of metro trains. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out research on the coupled behavior of metro trains–curve bridges with RW and the threshold of safe running speed.

Based on the theoretical research of the existing RW, the mechanical connection characteristics between the rim and the web of the RW are first discussed, and the mechanical model of the RW is established. Then, based on the train–track–bridge interaction theory, a metro train–track–curve bridge coupled dynamic model with RW is established. Finally, the coupled vibration characteristics of metro train–track–curve bridge with RW under long-short wave combined excitation are studied. The vibration suppression characteristics and compatibility of RW on curved bridge are discussed. The safe operation speed threshold of metro train passing through curved bridge considering RW is explored, which provides theoretical suggestions for the mechanical design of RW and the operation of metro trains, as shown in Fig. 1.

Metro train-CB coupled dynamic model with resilient wheel

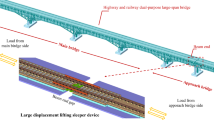

The metro train–curve bridge coupled dynamic model considering RW includes RW model, metro train model, track model and curve bridge model. At the same time, considering the wheel–rail relationship and the bridge–rail relationship, the interaction between the metro train, the track and the long-span bridge is realized. For example, Fig. 2 is the metro train–curve bridge coupled dynamic model considering the RW, in which the resilient rubber is simulated by spatial spring-damping connection.

Metro train-CB coupled dynamic model with RW. Image created using SolidWorks (Version: 2022), software provided by Dassault Systèmes (https://www.solidworks.com/).

Resilient wheel sub-model

The RW is composed of rim, rubber, and web via inlaying rubber layer inside the SW. The vibration isolation characteristics of rubber are utilized, the wheel–rail interaction is reduced. The RW rubber layer between the rim and the web is achieved by stiffness and damping, as shown in Figs. 3, 4. Since the deflection rim relative to web are only set to prevent the rim from falling off when the metro trains start and brakes, it has no effect on the vibration dynamics30. Therefore, the behavior of metro trains through curved bridge is considered, the rubber layer stiffness and damping of rim and web only consider axial and radial directions, as shown in Fig. 4.

Wheel structure characteristics: (a) Resilient wheel structure, (b) Sectional of solid wheel (SW) and resilient wheel (RW). Image (a) created using SolidWorks (Version: 2022), software provided by Dassault Systèmes (https://www.solidworks.com/). Image (b) created using Microsoft Visio (Version: Professional 2019), software provided by Microsoft Corporation (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/visio/flowchart-software).

Mechanical equation of rubber layer of RW

where

where, FL/FR and NL/NR are creep force and normal force on the left/right wheel rims, respectively. FhL/FhR are left/right RW rubber suspension force. FfL/FfR are left/right primary suspension force. ML and MR are left/right wheel creep torque. lt is half of the fixed distance of bogie wheelset. Htw is the vertical distance between the center of mass of the f bogie and the center line of the wheelset. Krw and Crw are rubber of RW stiffness and damping respectively. Rt represents the radius of curvature corresponding to the center of gravity of the wheel on the curved track. x, y, z represent longitudinal, lateral, and vertical respectively.

According to the force analysis of RW and Newton’s second law, the vibration differential equations of rim and web are obtained.

(1) Rim vibration equation:

(2) Web vibration equation:

where mass, moment of inertia, stiffness and damping are expressed by M, I, K, C respectively, and the subscript markers r, w, b and c represent the rim, web, bogie and car body respectively. The parameters dw and d0 are half of the lateral distance of the primary suspension and RW rubber suspension is half of the lateral distance, respectively. The parameters rr and rw are radius of rim and web, respectively. a0 is half of the distance between the left and right wheel–rail contact points.

Metro train sub-model

Based on the vehicle–track coupled dynamic theory31, the dynamic model of metro trains with RW are established. The model includes a car body, two bogies, four resilient wheelsets, a wheelset to contain two rims, and two webs (web and axle as a whole), there are 11 rigid bodies in total. Each rigid body considers 6 degrees of freedom (DOF), including lateral movement, heaving movement, rolling, yawing, and rotation. Therefore, the metro vehicle sub-model has 66 DOF are shown in Table 1.

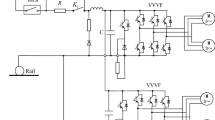

The primary suspension between the wheel and the bogie, and the secondary suspension between the bogie and the car body are connected by spring-damper. Figure 5 shows the dynamic model of the metro train considering the RW. Table 2 shows the symbols for various parameters of metro trains. Therefore, its dynamic equation can be expressed as:

where \(\ddot{X}v,\;\dot{X}v,\;Xv\) are the metro train acceleration vector, velocity vector, and displacement vector, \(Mv,\;Cv,\;Kv\) are the mass matrix, damping matrix, and stiffness matrix of the metro train system, respectively. ø, β, Ψ represent longitudinal, lateral, and vertical angular displacements respectively. g, w, b, and c are subscript of rim, web, bogie, and car body. M and I are mass and moment of inertia. Kp, Ks and Cp, Cs are primary and secondary suspension stiffness and damping respectively.

Track sub-model

Rail is regarded as an infinite Euler beam supported by elastic discrete32. Therefore, the vibration equation of rail is expressed by

where ErIr is rail stiffness, Zr(x,t) is the dynamic displacement of rail, Zb(x,t) is the bridge displacement, Ffi is the i th fastener force, Nf is the number of fasteners, pj is the j th wheel/rail force, x is the i th fastener coordinate, kp and cp are the stiffness and damping of each group of fasteners.

curved bridge sub-model

The finite element method is used to simulate the curved bridge substructure model, and the vibration differential equation is

where Mb, Cb, and Kb are the mass matrix, damping matrix, and stiffness matrix of the bridge system, respectively.\({\ddot{\text{X}}}_{b} ,{\dot{\text{X}}}_{b} ,{\text{X}}_{b}\) are the acceleration vector, velocity vector and displacement vector, respectively. The load vector of the Fb bridge is respectively. The mass matrix Mb and Mb and the stiffness matrix Kb of the bridge sub-model can be obtained by the bridge finite element model. Because it is difficult to accurately determine the damping matrix Cb in the actual analysis process, it is usually simplified as a linear combination of the mass matrix Mb and the stiffness matrix Kb of the bridge sub-model33,34, that is,

For the commonly used Rayleigh damping, α and β are respectively

where ω1, ω2, ξ1 and ξ2 are the first-order and second-order natural frequencies of the structure and the corresponding damping ratio, respectively. For concrete bridges, ξ1 and ξ2 generally take 2%–5%; for steel bridges, ξ1 and ξ2 generally take 2%–3%. So α = 0.06749, β = 0.005681 are calculated.

Numerical integration method

This work adopts the explicit–implicit mixed integration method to calculate the system. A new fast explicit integration method (Zhai method35) proposed by Academician Zhai WM is adopted to solve the metro train sub-model. Newmark-β implicit integration method is adopted to solve the curved bridge sub-model. The detailed iteration process is shown in the work35,36.

In addition, the time step of the two integral methods is 5 × 10−5 s to ensure the convergence and synchronization of the calculation.

Research conditions

Taking actual rail transit in Chongqing as the research object, the influence of RW on the dynamic characteristics of the metro train are studied. Table 2 shows the dynamic parameters of B-type metro trains, 3 cases of empty-load, full-load and over-load are considered. In the RW dynamics model, the rubber layer between the rim and the web is simulated via spatial spring-damping element simulation, whose stiffness and damping values are shown in Table 226,27.

The track irregularity excitation is excited by the American fifth-order spectral, which is a long-wave track irregularity excitation30. In the study of the high-frequency vibration of a wheel, based on predecessors, Sato obtained the fitting formula of short-wave spectral irregularity37. Therefore, to further research the high-frequency vibration characteristics of the RW, the long-short wave combined track excitation is obtained by considering Sato short-wave spectral irregularity basic on the American fifth-order spectral.

where A is the roughness coefficient, A = 4.15 × 10−8–5.0 × 10−7, and k is the spatial frequency.

To investigate the vibration suppression characteristics of the RW on the curved bridge and the threshold for safe operation, the curve line is set on the track38, as shown in Fig. 6. The straight segment is L1 = 100 m, the start transition curve is P11 = 60 m, the circular curve segment is S1 = 200, the circular curve radius is R1 = 350 m, the end transition curve is P12 = 60 m, and the track super-elevation is set to 0.12 m. The curved bridge is located in the middle of the circular curve section.

Based on the finite element theory and ANSYS 19.2, the mechanical model of a 30 m simply supported box-shaped curved bridge with a curve radius of 350 m is established, as shown in Fig. 7. The Soild185 element is adopted for simulation, and the mesh size is 0.15 m. The elastic modulus is 3.55 × 1010 Pa, the density is 2600 kg/m3, and the Poisson 's ratio is 0.2. Table 3 shows the first 10 natural frequencies and vibration modes of the curved bridge.

Mechanical model of curved bridge. Image created using ANSYS (Version: 19.2), software provided by ANSYS Inc (https://www.ansys.com/products/release-highlights/ansys-19-2).

Dynamic characteristics

The dynamic model of metro train–curve bridge considering SW and RW respectively is adopted, the dynamic characteristics of the metro train passing through the curved bridge at 60 km/h are calculated.

Because the significant difference in wheel–rail force and wheel dynamic characteristics between the inner and outer rails of metro trains passing through curved bridge under centrifugal force, to study the vibration suppression characteristics of the RW on the curved bridge in more detail, the vibration suppression characteristics of the RW on the curved bridge are studied in detail, the wheel–rail characteristics of the inner and outer rails and the dynamic characteristics of the inner and outer sides of the bridge are investigated respectively.

Metro train with resilient wheel

Figures 8 and 9 show the wheel–rail vertical forces of the inner and outer rails of the metro train (full-load) passing through the curved bridge with the SW and the RW, respectively. Figures 8a and 9a are the wheel–rail vertical force of the outer rail and the inner rail of the metro train passing through the whole curve track, respectively. It shows that the wheel–rail force under the action of the RW is smaller than that of the SW, and the wheel–rail vertical force of the RW on the curve track is reduced. The time range of the metro train running on the curved bridge is 17 s–19 s. The wheel–rail vertical forces of the outer rail under the action of the SW and the RW are 109.6 kN and 103.5 kN, respectively, the RW is 5.6% lower than the SW, see Fig. 8b. The wheel–rail vertical forces of the inner rail under the action of the SW and the RW are 92.3 kN and 89.6 kN, respectively, the RW is 5.6% lower than the SW, see Fig. 9b. The main frequency of the wheel–rail vertical force of the inner and outer rails under the action of the SW and the RW are 3.9 Hz, because the resonance caused by the first-order symmetrical vertical bending mode of the curved bridge, the wheel–rail vertical force of the RW at 40–140 Hz is smaller than that of the SW, as shown in Figs. 8c and 9c.

The wheel–rail lateral forces of the inner and outer rails of the metro train (full-load) passing through the curved bridge with the SW and the RW are shown, respectively, as shown in Figs. 10 and 11. Figures 10a and 11a are the wheel–rail lateral force of the outer rail and the inner rail of the metro train passing through the whole curve track, respectively. It shows that the wheel–rail lateral force of the RW is larger than that of the SW. The time range of the metro train running on the curved bridge is 17 s–19 s. The wheel–rail lateral forces of the outer rail under the action of the SW and the RW are 35.2 kN and 35.4 kN, respectively, see Fig. 10b. The wheel–rail lateral forces of the inner rail under the action of the SW and the RW are 22.9 kN and 28 kN, respectively, the wheel–rail lateral force of the inner rail of the RW is 18% higher than that of the SW, see Fig. 11b. The main frequency of the wheel–rail vertical force of the inner and outer rails under the action of the SW and the RW are 3.9 Hz and 7.5 Hz, because the resonance caused by the first-order symmetrical vertical bending mode and first-order torsion mode of the curved bridge, the wheel–rail lateral force of the inner rail of the RW at 40–140 Hz is smaller than that of the SW, as shown in Figs. 10c and 11c. Furthermore, the wheel–rail lateral force of the RW on the outer rail of 23H and 75 Hz has large peaks, as shown in Fig. 10c.

The time domain and time–frequency domain characteristics of the vertical acceleration of the inner and outer wheels are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. The difference in vertical acceleration between the inner and outer rails of the wheels is not significant, the effect of curve on wheel vertical acceleration is not significant, and the vertical acceleration of the rim is the highest, followed by the SW, and the smallest is the web, the damping characteristics of RW rubber are reflected, see Fig. 12a,b. The dominant frequencies of the vertical acceleration vibration of the SW, the rim and the web of the metro train passing through the curved track are about 25 Hz, 75 Hz and 25 Hz respectively. The vertical acceleration of the rim is the highest, followed by the SW, and the smallest is the web at the time–frequency domain. Within 10 s to 28 s, the vertical acceleration of the outer rail rim is more significant than the vibration of the inner rail rim at the main frequency of about 75 Hz. Then, this is the time when the metro train passing through the circular curve, as shown in Fig. 13.

Wheel vertical acceleration: (a) outer rail (b) inner rail. Image created using Origin (Version: 2021), software provided by OriginLab Corporation (https://www.originlab.com/2021).

The time domain and time–frequency domain characteristics of the lateral acceleration of the inner and outer wheels are shown in Figs. 14 and 15. The difference in lateral acceleration between the inner and outer rails of the wheels is significant, the lateral vibration of the wheel is exacerbated on the curved track, so the effect of curve on wheel lateral acceleration is significant, and the lateral acceleration of the rim is the highest, followed by the web, and the smallest is the SW, as shown in Fig. 14a,b. The dominant frequencies of the lateral acceleration vibration of the SW, the rim and the web of the metro train passing through the curved track are about 25 Hz, 75 Hz and 75 Hz respectively. The lateral acceleration of the rim is the highest, followed by the SW, and the smallest is the web at the time–frequency domain. In 10 s–28 s, the lateral acceleration of SW, rim and web is significantly higher than that in other time periods. Then, this is the time when the metro train passing through the circular curve track, and the lateral vibration of the wheel on the curved track is exacerbated as shown in Fig. 15. Moreover, the lateral vibration acceleration of the web is smaller than that of the SW at more than 100 Hz.

Curved bridge

Metro train–curve bridge coupled dynamic model with RW is adopted. The dynamic response of the metro train passing through the mid-span of the curved bridge at a speed of 60 km/h is calculated, including the outer side of the flange slab (OFS), the roof (R), the inner side of outer side of the flange slab (IFS), the outer side of the web (OW), the floor (F) and the inner side of the web (IW).

The time-domain characteristics of vertical vibration acceleration of metro trains passing through the midspan of curved bridge with both SW and RW is described in Fig. 16. The vertical acceleration of RW acting on curved bridge is smaller than that of SW, and the vertical vibration acceleration of various parts of curved bridge is reduced by RW. The vertical vibration acceleration of the IFS and the IW of a curved bridge is greater than that of the OFS and the OW, and the vertical vibration acceleration of the R is greater than that of the F. The R, F, IFS, OFS, IW, and OW of the curved bridge under the action of RW has been reduced by 20%, 19.5%, 18%, 21%, 32%, and 3% respectively.

Figure 17 shows the frequency domain results of vertical vibration acceleration at various positions in the midspan of curved bridge. The vertical vibration acceleration of curved bridge under the action of SW and RW has significant peaks at 3.9 Hz, 7.5 Hz, and 28 Hz, respectively, this is caused by first-order symmetrical vertical bending mode, first-order torsion mode and third -order symmetric vertical bending mode. The vertical vibration of the R and F are reduced by the RW at 60–140 Hz, the vertical vibration of the IFS, OFS, and IW are reduced by the RW at 38–140 Hz, and 40–200 Hz, and the effect of RW on the vertical vibration of OW is not significant.

The time-domain characteristics of lateral vibration acceleration of metro trains passing through the midspan of curved bridge with both SW and RW is described in Fig. 18. The lateral acceleration of IFS, OFS, IW, and OW acting on curved bridge by the RW are smaller than that of the SW. The lateral vibration acceleration of the IFS and the IW of a curved bridge are greater than that of the OFS and the OW. The R, IFS, IW, and OW of the curved bridge under the action of RW has been are increased by about 15%.

Figure 19 shows the frequency domain results of lateral vibration acceleration at various positions in the midspan of curved bridge. The lateral vibration acceleration of curved bridge under the action of SW and RW has significant peaks at 7.5 Hz and 12.5 Hz, respectively, this is caused by first-order symmetrical vertical bending mode and first-order lateral transverse bending mode. The lateral vibration of the R is reduced by the RW at 40–100 Hz, the vertical vibration of the F, IFS, OFS, IW and OW are reduced by the RW at 40–140 Hz.

Safe operation speed threshold

To study the safe operation of metro trains with RW through curved bridge, three train load cases of empty-load, full-load and over-load are calculated. From the perspective of the derailment coefficient and wheel unloading rate of the metro train running on the curved bridge, the safe speed threshold of the metro train passing through the curved bridge considering the RW are studied. The vehicle–bridge coupled dynamic characteristics of three cases at different speeds (40–80 km/h, with an interval of 5 km/h) are also discussed, and the vibration suppression characteristics and compatibility of the RW in the metro train–curve bridge are further studied.

The vertical wheel–rail forces, including those on both the inner and outer rails, exerted by metro trains equipped with SW and RW passing through curved bridges at various speeds (40 km/h to 80 km/h) under the conditions of empty-load, full-load, and over-load are considered, as illustrated in Fig. 20. The color mapping in the Fig. 20 indicates that the vertical wheel–rail force increases with the increase of load and speed, with the outer rail’s vertical wheel–rail force being greater than that of the inner rail. Under the three load conditions of empty-load, full-load, and over-load, the vertical wheel–rail force of the RW is less than that of the SW, further demonstrating that elastic wheels reduce the vertical wheel–rail force.

The lateral wheel–rail forces applied by metro trains with SW and RW through curved bridges at different speeds (40 km/h to 80 km/h) under empty-load, full-load, and over-load are considered, including the lateral wheel–rail forces on the inner and outer rails, as shown in Fig. 21. The results indicate that the wheel–rail lateral force increases with the increase of load and speed, and the trend of change in the wheel–rail lateral force on the outer rail is more significant than that on the inner rail. The wheel–rail lateral force on the outer rail is greater than that on the inner rail. Under the three load conditions of empty, full, and overloaded, the wheel–rail lateral force of the RW is greater than that of the SW.

The derailment coefficient of metro trains running on curved bridge considering SW and RW is described in Fig. 22. The derailment coefficient decreases with the increase of load and increases with the increase of speed. The derailment coefficient of the inner and outer wheels of the RW is smaller than that of the SW. The derailment coefficient of the outer rail wheel is higher than that of the inner rail wheel, metro train derailment accidents are more likely to be induced. However, the limit value of derailment coefficient for safe operation of metro train is 0.831, the derailment coefficients of the outer rail SW and the outer rail RW of the empty-load case are both exceeded the limit at speed exceeding 75 km/h. The derailment coefficient of the inner rail SW of the empty-load case is exceeded by the limit at speed exceeding 75 km/h, the derailment coefficient of the inner rail RW of the empty-load case is exceeded by the limit at speed exceeding 80 km/h. Therefore, to ensure the safe operation of metro trains with RW through curved bridge, it is recommended that the running speed does not exceed 75 km/h.

The wheel unloading rate and wheelset lateral force of metro trains running on curved bridge considering SW and RW is described in Fig. 23. The wheel unloading rate and wheelset lateral force decreases with the increase of load and increases with the increase of speed. However, the limit value of wheel unloading rate for safe operation of trains is 0.631, the wheel unloading rate of the RW of the empty-load case and full-load are both exceeded the limit at speed exceeding 70 km/h and 75 km/h. The wheel unloading rate of the SW of the empty-load case and full-load are both exceeded the limit at speed exceeding 75 km/h. Therefore, to ensure the safe operation of metro trains with RW through curved bridge, it is recommended that the speed does not exceed 70 km/h.

Therefore, the safety index of the metro train passing through the curved bridge are considered comprehensively. To further ensure the safety of metro train with RW passing through curved bridge, a certain safe operating speed margin is considered, and a safe operating speed threshold of 60 km/h is recommended.

The vertical and lateral acceleration of the outer SW, the inner SW, the outer rim, the inner rim and the web at different speeds and loads, respectively, as shown in Figs. 24 and 25. The vertical and lateral vibration accelerations of the wheels are aggravated with increasing speed and load. The vertical and lateral vibrations of the outer wheel are more intensity than those of the inner wheel under different loads and speeds, this is because the wheel–rail force of the outer rail is larger than that of the inner rail under the action of centrifugal force when the train passes through the curved bridge, and the interaction between the outer rail and the wheel is intensified. At different loads and speeds, the vertical acceleration of the rim is the largest, followed by the SW, and the smallest is the web, as shown in Fig. 24. However, the lateral acceleration of the wheel is shown to be the largest in the rim, followed by the web, and the smallest is the SW, as shown in Fig. 25.

Wheel vertical acceleration at different loads and speeds: (a) Empty-Load (b) Full-Load (c) Over-Load. Image created using Origin (Version: 2021), software provided by OriginLab Corporation (https://www.originlab.com/2021).

Wheel lateral acceleration at different loads and speeds: (a) Empty-Load (b) Full-Load (c) Over-Load. Image created using Origin (Version: 2021), software provided by OriginLab Corporation (https://www.originlab.com/2021).

Therefore, the vertical vibration acceleration of the wheel of the metro train considering the RW passing through the curved bridge is reduced, and the lateral vibration of the RW is amplified under the action of the wheel–rail lateral force at the action of the curved track.

Figure 26 shows the vertical acceleration of curved bridge caused by metro trains with SW and RW at different loads and speeds. The vertical acceleration of each position of the bridge is aggravated by large speed and load. The vertical acceleration of curved bridge at the action of RW is smaller than that of SW. The vertical acceleration of OW and F of curved bridge under the excitation of metro train with SW and RW is relatively small. The vertical acceleration of the curved bridge under the excitation of the SW and the RW at lower speed is close to that of the curved bridge under the excitation of the SW and the RW at lower speed, when the speed is higher, the vertical acceleration of the curved bridge is significantly reduced by the RW.

Figure 27 shows the lateral acceleration of curved bridge caused by metro trains with SW and RW at different loads and speeds. The lateral acceleration of each position of the bridge is aggravated by large speed and load. The lateral acceleration of OFS at the action of RW is smaller than that of SW, as shown in Fig. 27c. The lateral acceleration of the IFS, and F under the excitation of the SW and the RW at lower speed is close to that of the curved bridge under the excitation of the SW and the RW at lower speed, when the speed is higher, the lateral acceleration of the IFS, and F is significantly reduced by the RW, as shown in Fig. 27b,f. The effects of RW on R, IW, and OW lateral acceleration of curved bridge is not significant, as shown in Fig. 27a, d,e.

Conclusions and expectations

Conclusions

The mechanical relationship between the rim and the web in the RW is discussed. The metro train-CB coupled dynamic models with RW is established. The coupled dynamic characteristics and safe operation speed threshold of metro train-CB with RW are studied. The following conclusions are drawn from the research:

-

1.

When metro train with RW passing curved bridge is considered, the vertical wheel–rail force of RW is reduced, but the lateral wheel–rail force is amplified compared with the SW. The vertical vibration acceleration of the wheel is reduced, but the lateral vibration acceleration is increased. The vertical vibration acceleration of the rim is the largest, followed by the SW, and the smallest is the web; the lateral vibration acceleration of the rim is the largest, followed by the web, and the smallest is the SW.

-

2.

Based on the safety index of the train passing through the bridge, the derailment accident of the metro train with RW (under empty-load and full-load cases) passing through the curved bridge at a speed of more than 70 km/h is induced. In order to ensure that the metro train with RW safely passes through the curved bridge, the safety margin is retained. It is recommended that the speed of metro trains running on curved bridge does not more than 60 km/h.

-

3.

The vehicle–bridge coupled dynamic response is aggravated with the speed and load of metro train. Under the action of centrifugal force, the wheel–rail interaction force of the outer wheel is larger than that of the inner wheel, and the vibration acceleration of the outer wheel of the SW and the RW is also larger than that of the inner wheel. The vibration of the inner side of the curved bridge is greater than that of the outer side, and the vibration reduction effect of the RW on the inner side is more significant than that on the outer side. The vertical displacement of curved bridge is reduced via RW.

-

4.

The RW has a vibration absorption effect on the wheel–rail vertical force within 40–140 Hz, and has no significant effect on the wheel–rail lateral force. The main frequencies of vertical vibration acceleration of SW, rim, and web are 25 Hz, 75 Hz, and 25 Hz respectively. At a frequency of 40–140 Hz, the RW has a damping effect on the vibration of the curved bridge, especially on the outer side of the flange slab of curved bridge.

Expectations

Due to page limitation, the influence of different curve radius bridges (such as track super-elevation, etc.) on the coupled dynamic characteristics and safe operation speed threshold of metro train-CB considering RW is also considered. In further research, more radius curved bridge will be concerned to expand the application of RW in metro train systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Dimitrakopoulos, E. G. & Zeng, Q. A three-dimensional dynamic analysis scheme for the interaction between trains and curved railway bridges. Comput. Struct. 149, 43–60 (2015).

Zeng, Q., Yang, Y. B. & Elias, G. D. Dynamic response of high speed vehicles and sustaining curved bridges under conditions of resonance. Eng. Struct. 114, 61–74 (2016).

Zhai, W. M. et al. Experimental investigation on vibration behaviour of a CRH train at speed of 350 km/h. Int. J. Rail Transp. 3(1), 1–16 (2015).

Maksym, S. et al. Implementation of roughness and elastic–plastic behavior in a wheel–rail contact modeling for locomotive traction studies. Wear 532–533, 205115 (2023).

Song, Q. F. et al. Study on rail corrugation on curved tracks on metro ramps. Wear 523, 204769 (2023).

Van-Vuong, L. et al. A nonlinear FE model for wheel/rail curve squeal in the time-domain including acoustic predictions. Appl. Acoust. 179, 108031 (2021).

Liu, W. F. et al. A frequency-domain formulation for predicting ground-borne vibration induced by underground train on curved track. J. Sound Vib. 549, 117578 (2023).

Yuan, Z. H. et al. Analytical solution for calculating vibrations from twin circular tunnels. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 117, 312–327 (2019).

Virajan, V., Nallasivam, K. & Khair, U. F. W. Forecasting fatigue life of horizontally curved thin-walled boxgirder railway bridge exposed to cyclic high-speed train loads. Struct. Integr. Life 23(3), 335–342 (2023).

Sugiyama, H. et al. Wheel/rail contact geometry on tight radius curved track: Simulation and experimental validation. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 25, 117–130 (2011).

Zhai, Z. H., Cai, C. B. & Zhu, S. Y. Implementation of Timoshenko curved beam into train-track-bridge dynamics modelling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 247, 108158 (2023).

Meehan, P. A. Prediction of wheel squeal noise under mode coupling. J. Sound Vib. 465, 115025 (2020).

Zima, R., Fajkoš, R., Karwala, K. & Michnej, M. New generation of resilient wheels bonatrans for tram cars. Rail Veh. 2, 55–59 (2013).

Bouvet, P. et al. Optimization of resilient wheels for rolling noise control. J. Sound Vib. 231(3), 765–777 (2000).

Calvo, F., Eboli, L., Forciniti, C. & Mazzulla, G. Factors influencing trip generation on metro system in Madrid (Spain). Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 67, 156–172 (2019).

Lucas, W. D. Estimating the price elasticity of demand for subways: Evidence from Mexico. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 87, 103651 (2021).

Thompson, D. J. & Gautiter, P. E. Review of research into wheel/rail rolling noise reduction. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit. 220(4), 385–408 (2006).

Remington, P. J. Wheel/rail rolling noise, I: Theoretical analysis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 81(6), 1805–1823 (1987).

Suarez, B., Chover, J. A., Rodriguez, P. & Gonzalez, F. J. Effectiveness of resilient wheels in reducing noise and vibrations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit. 225, 545–565 (2011).

Wen, J., Li, F., Yang, Y. & Ding, J. J. Research on parameter optimization and line adaptability of resilient wheels for urban rail vehicles. Locomot. Electr. Drive 244(03), 74–77 (2015) ((in Chinese)).

Hu, X., Xue, Z. & Zhang, J. Dynamic model of resilient wheel and its performance comparison. Proceedings of the 2022 Joint Rail Conference. 2022 Joint Rail Conference. Virtual, Online. April 20–21, 2022. V001T04A003. ASME. https://doi.org/10.1115/JRC2022-79357

Zhou, X., Zhong, S. & Sheng, X. An investigation into the effect of resilient wheel stiffness on the dynamic behaviour of a metro vehicle running along a tangent track. J. Vib. Control 29(13–14), 3298–3311 (2023).

Xiao, G., Xu, L., Wu, B., Yao, L. & Xin, Z. Dynamic behavior of resilient wheels at a rail weld joint. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit. 235(8), 925–945 (2021).

Tian, J. H., Wang, K. & Xiao, K. Analysis of vibration and sound radiation characteristics of resilient wheel in metro. Am. J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 3(4), 55–55 (2018).

Tian, J. & Dong, X. Research on polygon suppression of resilient wheels under multiple operating conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-body Dyn. 237(2), 371–385 (2023).

Chen, Z. W. & Pu, Q. H. Vibration absorption performance of resilient wheel in metro train running on long-span cable-stayed bridge. Int. J. Rail Transp. 11(1), 129–149 (2023).

Chen, Z. W. et al. Dynamic behavior of metro train–LSB (long-span bridge) system considering nonlinearity of resilient wheel. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455424500020 (2023).

Holger, C. & Werner, S. Dynamic stability and random vibrations of rigid and elastic wheelsets. Nonlinear Dyn. 36, 299–311 (2004).

Kouroussis, G., Verlinden, O. & Conti, C. Efficiency of resilient wheels on the alleviation of railway ground vibrations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F: J. Rail Rapid Transit. 226(4), 381–396 (2012).

Zhou, X. et al. Characteristics of vibration and sound radiation of metro resilient wheel. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 32(1), 1–12 (2019).

Zhai, W. M. Vehicle-Track Coupled Dynamics (Science Press, 2020).

Zhai, W. M. Two simple fast integration methods for large-scale dynamic problems in engineering. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 39(24), 4199–4214 (1996).

Zhai, W. M. et al. Train-track-bridge dynamic interaction: A state-of-the-art review. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 57(7), 984–1027 (2019).

Wu, Y. X. et al. Research on the cross-sectional geometric parameters and rigid skeleton length of reinforced concrete arch bridges: A case study of Yelanghu Bridge. Structures 69, 107423 (2024).

Arvidsson, T. & Karoumi, R. Train-bridge interaction—A review and discussion of key model parameters. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2(3), 147–186 (2014).

He, Q. L. et al. A novel modelling method for heavy-haul train-track-long-span bridge interaction considering an improved track-bridge relationship. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 220, 111691 (2024).

Sato. Study on high-frequency vibration in track operation with high-speed trains. Q. Rep. RTRI. 18(3), 109–114 (1997).

Wang, Z. & Lei, Z. Formation mechanism of metro rail corrugation based on wheel–rail stick–slip behaviors. Appl. Sci. 11, 8128 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant Number 2024JJ7077); the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province, China (Grant Numbers 23B0732 and 22B0793).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wu Y.X. and Pu Q.H. conceptualized and designed the research; Chen Z.W. performed the research and analyzed data; Pu Q.H. wrote the initial paper draft; Wu Y.X., Pu Q.H., Hong X.M., and Wang X.Z. reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Pu, Q., Chen, Z. et al. Dynamic characteristics and safe operation speed threshold of metro train passing through curved bridge considering resilient wheel. Sci Rep 15, 3818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86572-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86572-0