Abstract

The use of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) has demonstrated effectiveness in the management of femoral head osteonecrosis as well as nonunion fractures; however, the effects of PEMF on preventing glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) have not been extensively studied. The aim of this investigation was to explore the effectiveness of PEMF stimulation in averting GIOP in rats and uncover the potential fundamental mechanisms involved. A total of seventy-two adult male Wistar rats composed the experimental group and were subsequently assigned to three groups for treatment. (1) On the first day (day 0), 24 rats in the PEMF group were intravenously injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at a concentration of 10 μg/kg. This was followed by intramuscular injections of methylprednisolone acetate (MPSL) at a dose of 20 mg/kg for the subsequent three days (days 1–3). Subsequently, the rats were exposed to PEMF for 4 h daily, with the duration varying from 1 to 8 weeks. (2) Adhering to the injection schedule of the PEMF group, the MPSL group (consisting of 24 rats) was administered LPS and MPSL, omitting PEMF stimulation. (3) The PS group (n = 24) was administered injections of 0.9% saline solution in an identical manner and at the same time intervals as the other two groups. At 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after the last MPSL (or saline) injection, bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC), and the expression levels of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) mRNA and protein in the proximal femur were measured. Analysis of the PS and PEMF groups at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after the final saline (or MPSL) injection revealed no statistically significant differences in BMD or BMC (P > 0.05). From weeks 2 through 8, the MPSL group rats displayed a marked decrease in BMD and BMC compared to those of the PS group, and at the 4-week and 8-week time points, these values were significantly lower than those of the PEMF group (P < 0.05). Compared with those in the MPSL and PS groups, the expression levels of BMP-2 mRNA markedly increased after PEMF treatment, peaking one week later and sustaining a heightened state for four weeks, but decreased only at the eighth week. Conversely, BMP-2 protein expression exhibited a similar upward trend, peaking two weeks after PEMF treatment and then remaining elevated for the subsequent eight weeks. PEMF stimulation has been shown to have prophylactic potential against GIOP in rats, possibly through the upregulation expression of BMP-2 expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoporosis, a highly prevalent bone disease across the globe, is characterized by low bone mineral density and compromised bone microstructure, ultimately culminating in fractures due to bone fragility1. The classification of osteoporosis comprises both primary and secondary forms, of which GIOP is the most common secondary variety2. Despite being a crucial therapy for illnesses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), arthritis, asthma, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)3, the adverse effects of glucocorticoid treatment, namely, GIOP, remain a significant concern that cannot be overlooked. Over the past few years, the incidence of GIOP has increased significantly, exhibiting a growing trend among younger individuals4,5,6. The occurrence of fractures due to osteoporosis can result in substantial costs, especially for hip fractures. By comparison, averting osteoporosis appears to be a superior method for addressing this disease, as it incurs notably lower costs and boosts patients’ quality of life. Unfortunately, a viable clinical method for the prevention and therapeutic management of GIOP has yet to be discovered7,8.

PEMF therapy has gained widespread adoption in treating nonunion fractures, osteoarthritis and femoral head osteonecrosis9,10,11,12, exhibiting no additional adverse effects13. Although we have previously documented the capacity of PEMF to prevent steroid-induced osteonecrosis in rats14, our understanding of its efficacy in preventing GIOP remains limited. Moreover, the precise mechanisms by which PEMF stimulation prevents GIOP have yet to be clarified. As a well-established growth factor, BMP-2 effectively promotes bone regeneration and augments bone density and resilience15,16. In vivo, it is crucial for governing osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, and is commonly employed in the treatment of osteoporosis and its sequelae. We suggest that PEMF could be a valuable treatment for preventing GIOP, and we posit that its mechanism of action lies in promoting the expression of BMP-2. In cases where patients with arthritis, asthma, or SLE require high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, PEMF may be administered concomitantly to help prevent the development of GIOP.

The hypothesis of our research was to investigate the preventive role of PEMF in GIOP. We hypothesize that PEMF therapy would lead to a significant increase in BMD and relative BMC in the proximal femur, accompanied by an upregulation of BMP-2 mRNA and protein levels, thereby preventing the occurrence of GIOP.

Methods

Animals

A total of seventy-two male adult Wistar rats (obtained from the experimental animal center of Wuhan University), aged 8 weeks and weighing approximately 250–280 g, participated in this research. The sample size of 72 rats was chosen based on previous experimental studies, particularly our own previously published papers14, which employed a similar number of animals. We chose male rats as our animal model for several reasons. Firstly, gender differences can affect bone metabolism and responses to treatments, so using only males helped minimize variability and focus on the effects of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) stimulation on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP). Secondly, previous studies on GIOP models have often used male animals due to their predictable responses to glucocorticoid treatment, allowing us to build upon existing knowledge. Lastly, male rats facilitate easier handling and housing.

The rats were individually housed in customized Plexiglas cages and kept in a stable environment with a 12-h light–dark cycle, a temperature of 24–25 °C, and humidity fluctuating between 50 and 55%. During the entire study, the rats had unrestricted access to food and water. The experimental methods were approved by the Animal Administration Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (ethical review No. 1-233), and were carried out in accordance with the Animals Act 1986, the National Institutes of Health Laboratory Animal Application Guidelines and the Regulations for the Administration of Afairs Concerning Experimental Animals published by the State Science and Technology Commission of China, and the ARRIVE guidelines.

Grouping and treatment

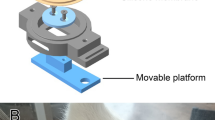

On the initial day, forty-eight rats received an intravenous injection of 10 μg/kg LPS, followed by intramuscular administration of 20 mg/kg MPSL acetate to the right gluteus medius muscle for three days, was administered at 24-h intervals14. Subsequently, the rats were segregated into two distinct groups and subjected to the respective treatment protocols. (1) The PEMF group (n = 24) underwent 4-h daily PEMF stimulation sessions beginning one day after the last methylprednisolone injection and continuing for a duration of 1 to 8 weeks. (2) The MPSL group (n = 24) did not receive any further intervention after the methylprednisolone injection. A control cohort comprising 24 rats that received injections of 0.9% saline following the same protocol and at identical intervals was used and designated the PS group. The protocol of pulsed electromagnetic field stimulation in this study was chosen according to that reported effective for steroid-induced osteonecrosis14,17, specifically featuring a frequency of 15 Hz, with each pulse involving a magnetic field that increased from 0 to 12 G in 4.5 ms and then decreased back to 0 in 20 ms. Each day, the rats belonging to the PEMF group underwent a 4-h session of pulsed electromagnetic field exposure, whereas the control rats were kept in similar cages and did not receive any kind of stimulation. The rationale for selecting a 4-h daily treatment duration was also derived from previous studies on PEMF therapy for steroid-induced osteonecrosis14. This duration was chosen to ensure adequate exposure to the PEMF while minimizing potential discomfort or inconvenience for the rats. One, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after the last saline (or MPSL) injection, six rats from each group were humanely euthanized using a lethal dose of pentobarbital sodium, and the bilateral femurs were removed for analysis.

The timepoints of 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks were chosen to capture critical stages of GIOP and the potential preventive effects of PEMF. The 1-week baseline establishes initial bone status, 2 weeks assesses early changes, 4 weeks evaluates intermediate effects, and 8 weeks evaluates long-term outcomes. This temporal sampling strategy provides a comprehensive analysis of PEMF’s preventative capabilities against GIOP.

Bone mineral measurements

Immediately following soft tissue dissection, the proximal 20% segment of the right femur was measured and extracted for subsequent bone mineral measurement. Using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) with high-resolution small animal software, the BMD and relative BMC of the proximal segment of the right femurs were quantified. The specific scanning parameters used in our study were as follows: a voltage of 100 kV, a current of 0.188 mA, and a dose of 10 μGy. To ensure consistency and minimize operational variability, all samples were assessed and measured by the same technician, who adhered to an identical protocol. Each rat was measured three times consecutively. The average of the three measurements was taken as the final data.

Histology

Immediately after bone densitometry analysis, the proximal segment of the right femur was fixed in 4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde and subsequently decalcified with 10% neutral buffered ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Subsequently, the specimens underwent dehydration through a series of increasing ethanol concentrations, were embedded in paraffin wax, and were then sliced into 5 μm coronal sections, with specific sections from the central location being selected for further staining procedures. The hematoxylin and eosin(HE) staining procedure was as follows: (1) Baking: The tissue sections were placed on a slide holder and baked in an oven at 62 °C for 45 min; (2) Dewaxing: The sections were placed in xylene for 10 min, with this step repeated three times; (3) Hydration: The sections were sequentially placed in 100% ethanol (I), 100% ethanol (II), 95% ethanol, 85% ethanol, and 75% ethanol for 5 min each; (4) The sections were placed in distilled water for 5 min, with this step repeated three times; (5) Hematoxylin solution was added dropwise, and staining was performed for 5 min; (6) The sections were rinsed in distilled water until the water was clear; (7) Eosin staining: The sections were placed in 75% ethanol for 4 min, 85% ethanol for 4 min, 95% ethanol for 4 min, 1% eosin solution for 1 min, 95% ethanol for 4 min, and 100% ethanol for 4 min; (8) Clearing: The sections were placed in xylene for 4 min, with this step repeated two times; (9) Mounting: Neutral balsam was added dropwise to bond the cover glass to the slide. After staining with HE, the sections were observed and analyzed using a light microscope.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The upper third segment of the left femur, without prior fixation, was instantly plunged into liquid nitrogen for freezing and kept at −80 °C to facilitate subsequent isolation of mRNA and proteins. Before pulverization commenced, the samples were rigorously weighed and then ground using a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen conditions, ensuring a setting free from RNase. We rigorously followed the manufacturer’s guidelines for the extraction of total RNA utilizing TRIzol Reagent. Subsequently, the RNA amount was quantified by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm, referred to as A260. The ratio of the absorbance at 260 nm to that at 280 nm (A260/A280) served as an indicator of RNA purity. If the ratio falls within the range of 1.8–2.0, it suggests that the extracted RNA has a high concentration and that components such as phenol and proteins have been removed relatively cleanly, making it suitable for subsequent experiments. The structural integrity and molecular size distribution of the RNA were examined via formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis. The ratio of the absorbance values between 28 and 18S rRNA is approximately 2. This indicates that the extracted total RNA has good integrity, high quality, and has not undergone degradation, making it suitable for subsequent experiments. The RNA was subsequently stained with ethidium bromide for visualization. cDNA was successfully synthesized using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. For PCR analysis, forward and reverse primers targeting BMP-2 and β-actin were used, as listed in Table 1. The selection of internal reference genes was based on our previous research14, hence no further validation was conducted. The reaction protocol began with an initial 5-min denaturation phase at 94 °C, followed by multiple amplification cycles, each of which included 30 s of denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s of annealing at 60 °C, and 45 s of extension at 72 °C. An additional final extension phase was conducted at 72 °C for 10 min. Amplification was carried out for 35 cycles for BMP-2 and 30 cycles for β-actin. Using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, the PCR amplification products were analyzed, followed by ethidium bromide staining for visualization and subsequent imaging with a Geliance Imaging System. Quantitative analysis of the band intensities was performed using Quantity One 4 software package (https://www.bio-rad.com/zh-cn/sku/1709604-quantity-one-4-user-network-license?ID=1709604). Gene expression levels are expressed as the ratio of the optical density of BMP-2 to that of β-actin.

Western blot analysis

The proximal one-third sections of the left femurs were dissected and manually pulverized in liquid nitrogen and subsequently homogenized in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation buffer that contained phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and a protease inhibitor cocktail. At 4 °C and 14,000 rpm, the samples were subjected to two rounds of centrifugation, each lasting 10 min. The supernatant was subsequently isolated, and 5 × loading buffer was added to a quarter of the volume. The mixture was heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then stored at −20 °C for potential use in electrophoresis procedures. Protein quantification was performed using the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) method, which involves measuring the absorbance value at a wavelength of 562 nm with visible light and comparing it to a standard curve to obtain the total protein concentration of different samples. Based on the results of protein quantification, the solution containing 50 μg of protein was calculated as the loading amount for each lane. Using a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel, proteins were separated via electrophoresis and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 2% bovine serum albumin, the membrane was incubated with rabbit anti-BMP-2 (dilution ratios 1:500) or rabbit anti-β-actin (dilution ratios 1:500) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated for 1 h with peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (dilution ratios 1:2000) at 25 °C. After utilizing an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) plus kit for detection, the exposure time was set to 1 to 2 min, and the exposure temperature was maintained at 20–25 °C. The proteins on the membrane were imaged on X-ray film and then captured digitally using a Geliance Imaging System. The analysis of band optical density was performed using the Quantity One 4 software package (https://www.bio-rad.com/zh-cn/sku/1709604-quantity-one-4-user-network-license?ID=1709604). The BMP-2 expression level was normalized to the β-actin expression level.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. The statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 26.0 (https://www.ibm.com/cn-zh/spss?lnk=flatitem). We incorporated the Shapiro–Wilk test as our method for assessing data normality, conducted Levene’s test to ensure homogeneity of variances, applied the Bonferroni correction to mitigate the increased risk of Type I errors due to multiple comparisons, and calculated Cohen’s d as an indicator of effect size in our statistical analysis. To assess group differences, we conducted one-way ANOVA supplemented with Turkey’s test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was achieved for all tests with a P-value less than 0.05.

Results

BMD and BMC of the proximal femur

During the experimental phase, no rat died, ensuring complete survival. The BMD and BMC values of the proximal femur are presented in Fig. 1, Tables 2 and 3. At 1 week post-injection, no statistically significant differences were observed between the PEMF and PS groups in terms of BMD and BMC (P > 0.05). Similarly, at 2 weeks post-injection, the differences remained non-significant (P > 0.05). However, from 2 weeks onwards, the MPSL group exhibited a downward trend in both BMD and BMC values. Specifically, at 4 weeks post-injection, the MPSL group had significantly lower BMD and BMC values compared to the PS group (P < 0.05). Additionally, at this time point, the PEMF group also showed significantly higher BMD and BMC values than the MPSL group (P < 0.05), indicating a protective effect of PEMF against bone loss. Furthermore, at 8 weeks post-injection, the differences between the groups became more pronounced. The MPSL group continued to have significantly lower BMD and BMC values compared to both the PS and PEMF groups (P < 0.05 for both comparisons). These findings suggest a time-dependent effect of MPSL on bone mineral status, with PEMF providing a beneficial effect in mitigating this decline.

Histological observation of the proximal femur

At week 1, no pathological differences were observed among the three groups of rats. However, starting from week 2, and subsequently at weeks 4 and 8, all rats in the MPSL group began to exhibit varying degrees of cartilage erosion. This destruction showed a trend of worsening over time. In contrast, the other two groups consistently demonstrated undamaged cartilage and intact bone trabecula throughout the study period. All assessments were performed by a single experienced observer to ensure consistency in evaluation criteria and minimize bias due to inter-observer variability.

Figure 2 shows the histological images of the proximal femur tissue from the three groups at week 8. Within the MPSL group, cartilage erosion was observed, and the bone trabecula of the proximal femur appeared sparse or fractured. The samples obtained from the PEMF group were healthy and were characterized by undamaged cartilage and intact bone trabecula.

mRNA expression of BMP-2

Over the period from weeks 1 to 8, a marked decrease in BMP-2 mRNA expression was observed in the MPSL group compared to the PS group (P < 0.05). From weeks 1 to 8, the PEMF group displayed a statistically significant increase in BMP-2 mRNA expression compared to the MPSL group (P < 0.05). Moreover, in the initial four weeks after PEMF stimulation, the expression levels were notably greater than those in the PS group (P < 0.05), as illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 4.

mRNA expression of BMP-2 in the proximal femur. (Original gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3). (A) Quantification of BMP-2 mRNA expression was carried out through PCR analysis. The PCR marker, labeled M, indicates size standards ranging from 250 bp at the bottom to 500 bp at the top. (B) The data are represented as expression ratios, which were standardized against β-actin gene expression and are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). #: P < 0.05 versus the PS group, *: P < 0.05 versus the MPSL group.

Protein expression of BMP-2

From weeks 1 through 8, the PEMF group exhibited significantly greater BMP-2 protein expression than did the MPSL and PS groups (P < 0.05). Compared with the other two groups, the MPSL group displayed significantly lower BMP-2 protein expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4 and Table 5).

BMP-2 protein expression in the proximal femur. (Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4). (A) Western blotting was used to assess the levels of BMP-2 protein expression. (B) The data are expressed as ratios normalized to β-actin protein levels, and the results are displayed as the average ± standard deviation (n = 6). #: P < 0.05 versus the PS group, *: P < 0.05 versus the MPSL group.

Discussion

Osteoporosis is a bone disease that involves bone mass loss and structural weakening, resulting in bones that are more fragile and prone to fractures18. An imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation plays a significant role in the progression of various types of osteoporosis, ultimately leading to a decrease in bone mineral density and overall bone strength19. Glucocorticoid medication, which has anti-inflammatory effects, is a commonly administered therapeutic for a wide array of illnesses, such as arthritis, lupus, and respiratory disorders such as asthma3. Based on previous investigations, glucocorticoid therapy diminishes bone formation and intensifies bone resorption, resulting in negative calcium homeostasis and heightened vulnerability to fractures20. Immediately upon glucocorticoid treatment, bone loss sets in rapidly, increasing the likelihood of fractures, while prolonged glucocorticoid administration contributes to the onset of osteopenia. Previous research has suggested that a low dose of glucocorticoids notably curtails bone formation, presumably due to diminished bone remodeling, which has implications for bone strength21,22. In our investigation, following glucocorticoid administration, the rats in the MPSL group exhibited cartilage erosion, and the bone trabeculae in the proximal femur were either infrequent or disrupted. Currently, numerous pharmacological modalities are available for the treatment of osteoporosis, including calcium, vitamin D, bisphosphonates, hormone replacement therapy, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, and raloxifene23. However, the extended use of osteoporosis medications is associated with potential adverse effects, including atypical femoral fractures in the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal region, gastrointestinal distress, and necrosis of the jawbone24.

Apart from pharmacotherapy, physical therapy that incorporates safe and nonintrusive biophysical interventions should be strongly advocated for clinical use. Compared to pharmacological interventions, PEMFs are considered an effective treatment modality for a wide range of bone conditions, including fresh fractures, fractures with delayed healing or failure to unite, diabetic osteopenia, and bone necrosis25. To date, there is a lack of clarity regarding the effects PEMF exerts on patients with GIOP. PEMFs, with their beneficial effects as a form of mechanical stimulation for bone mass preservation, have potential for clinical use in preventing and managing osteoporosis25,26. This research aimed to examine the preventative impact of PEMF on GIOP in rats, while delving into the mechanisms responsible. Inspired by the report published by Ishida et al., the PEMF parameters were chosen based on their observation that PEMF can lower the chances of steroid-induced osteonecrosis17. Guided by our preceding research, we kept the electromagnetic frequency constant while modifying the daily stimulation interval from 10 to 4 h14.

Monitoring the BMD and BMC in the proximal femur of the rats revealed a progressive decrease in the MPSL group, starting at week 2 and attaining the lowest values by week 8. A marked statistical distinction was observed in comparison to the remaining two groups, suggesting that the administration of glucocorticoids diminishes BMD and BMC in rats, thereby contributing to the development of GIOP. In contrast, compared with those in the PS group, the BMD and BMC in the PEMF group did not significantly differ at any measurement point, and these values were markedly greater than those in the MPSL group at weeks 4 and 8. Hence, we are convinced that PEMF has the potential to counter glucocorticoid-mediated bone loss, thereby sustaining BMD and BMC within normal levels.

BMP-2, a growth factor that accelerates bone renewal and boosts bone robustness and density, has garnered widespread application in the treatment of osteoporosis and its associated conditions15,16. Among the numerous significant markers related to bone health, including BALP, osteocalcin, NTX, and Vitamin D, BMP-2 was selected for assessment in this study due to its pivotal role in regulating bone formation and its direct relevance to the specific research questions we aimed to address. BMP-2's established role in promoting osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration, as well as its upregulation in response to bone injury, made it a particularly suitable marker for evaluating the effects of our experimental interventions.

Because of its fleeting half-life and inadequate retention capability, BMP-2 is unsuitable for administration as a standalone injection27. Additionally, the direct administration of large quantities of BMP-2 can result in severe complications and side effects. PEMF, a noninvasive therapeutic method, exhibits endocrine-like actions, promoting the a sustained secretion of cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and BMP-2, that aid osteoblast differentiation in bone tissue affected by a fracture, thus facilitating bone tissue reparative processes28. However, the precise mechanism responsible for PEMF mediated enhancement of bone formation, specifically in GIOP treatment, is still not fully understood. The findings of our investigation revealed a downregulation of BMP-2 mRNA and protein expression in the MPSL cohort, whereas an upregulation was observed in the PEMF group. Hence, there is a significant probability that PEMF stimulation boosts BMP-2 expression in the proximal femur area of rats given glucocorticoids, playing a role in the prevention of GIOP, likely constituting one of the key mechanisms involved. As a prophylactic measure, PEMF could be administered alongside glucocorticoids for the management of various clinical disorders, including arthritis, asthma, and SLE, for which high-dose glucocorticoid therapy is necessary.

While our study has focused on the potential benefits of PEMF application in preventing GIOP, it is important to also consider the safety aspects of long-term use. PEMF therapy is generally considered safe and non-invasive, with minimal reported side effects such as mild skin irritation or discomfort in some cases. However, long-term exposure to PEMF may raise concerns related to potential cumulative effects on tissue or cellular function. To date, there is limited research specifically addressing the long-term safety of PEMF application. Therefore, while our findings suggest promising benefits of PEMF in preventing GIOP, caution should be exercised in extrapolating these results to long-term use without additional safety data.

Our study findings suggest that PEMF stimulation can prevent GIOP in rats. However, several potential limiting factors need to be considered when translating these results into clinical practice. First, the sample size in our study was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to larger populations. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our results and explore potential variations across different patient groups. Second, it is important to acknowledge the inherent differences between rats and humans in terms of physiology, metabolism, and disease progression. These species-specific differences may affect the applicability of our findings to human patients. The specific conditions and environment in which the rats were studied may not fully represent the complex clinical scenarios encountered in human patients. Therefore, further clinical trials in humans are necessary to validate our findings and establish the safety and efficacy of the treatment in a clinical setting. While our study offers preliminary indications that PEMF stimulation may prevent GIOP, several potential limiting factors must be taken into consideration in future research endeavors to comprehensively grasp the clinical ramifications of our discoveries.

Our study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the lack of microCT data significantly limits our ability to fully characterize bone microarchitecture, which is a crucial aspect for understanding bone quality and strength. MicroCT provides high-resolution images of bone structure, allowing for detailed analysis of trabecular thickness, spacing, and connectivity, all of which are important indicators of bone mechanical properties. The absence of these data in our study means that we are unable to comprehensively assess the impact of PEMF on bone microstructure. To address this limitation, future studies should incorporate microCT analysis to provide a more detailed and comprehensive view of bone structural changes. This would enable a more accurate assessment of bone quality and strength. Secondly, we acknowledge that our histological assessment relied on qualitative observations, which may be subject to inter-observer variability. Furthermore, the lack of histological scoring criteria and the absence of blinded assessment are additional limitations in our study. Incorporating objective quantitative measurements and developing standardized scoring criteria would strengthen the rigor of our histological analysis and enhance the reliability of our findings. Thirdly, a notable limitation of this study is the absence of preliminary experimental data exploring the dose–response relationships of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) stimulation in the context of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Future research should investigate the effects of varying PEMF parameters to identify the optimal dose and duration for therapeutic efficacy. Fourthly, the exclusion of additional blood markers limits our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and severity of bone changes. Lastly, Detection bias might also be a concern, given potential differences in the sensitivity or specificity of the methods used to measure BMD, BMP-2 mRNA and protein expression. In future studies, we plan to mitigate this bias by using more sensitive test methods.

Conclusions

PEMF stimulation can prevent GIOP in rats, and the underlying mechanisms increased the expression of BMP-2. PEMF stimulation is both effective and safe without the need for invasive procedures, serves as a beneficial prophylaxis for GIOP.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PEMF:

-

Pulsed electromagnetic field

- GIOP:

-

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MPSL:

-

Methylprednisolone acetate

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- BMC:

-

Bone mineral content

- BMP-2:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein-2

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ECL:

-

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- TGF-β1:

-

Transforming growth factor-β1

References

Eastell, R. et al. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16069 (2016).

Anastasilaki, E., Paccou, J., Gkastaris, K. & Anastasilakis, A. D. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: An overview with focus on its prevention and management. Hormones (Athens) 22(4), 611–622 (2023).

Cho, S. K. & Sung, Y. K. Update on glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 36(3), 536–543 (2021).

Buckley, L. et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 69(8), 1521–1537 (2017).

Chotiyarnwong, P. & McCloskey, E. V. Pathogenesis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and options for treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 16(8), 437–447 (2020).

Kubo, T. et al. Clinical and basic research on steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head in Japan. J Orthop Sci 21(4), 407–413 (2016).

Adami, G. & Saag, K. G. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis update. Curr Opin Rheumatol 31(4), 388–393 (2019).

Song, L. et al. The critical role of T cells in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Cell Death Dis 12(1), 45 (2020).

Mohajerani, H., Tabeie, F., Vossoughi, F., Jafari, E. & Assadi, M. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic field on mandibular fracture healing: A randomized control trial, (RCT). J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 120(5), 390–396 (2019).

Pan, X., Xiao, D., Zhang, X., Huang, Y. & Lin, B. Study of rotating permanent magnetic field to treat steroid-induced osteonecrosis of femoral head. Int Orthop 33(3), 617–623 (2009).

Umiatin, U., Hadisoebroto Dilogo, I., Sari, P. & Kusuma Wijaya, S. Histological analysis of bone callus in delayed union model fracture healing stimulated with pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF). Scientifica (Cairo) 2021, 4791172 (2021).

Wang, T., Xie, W., Ye, W. & He, C. Effects of electromagnetic fields on osteoarthritis. Biomed Pharmacother 118, 109282 (2019).

Zhang, T., Zhao, Z. & Wang, T. Pulsed electromagnetic fields as a promising therapy for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 11, 1103515 (2023).

Ding, S., Peng, H., Fang, H. S., Zhou, J. L. & Wang, Z. Pulsed electromagnetic fields stimulation prevents steroid-induced osteonecrosis in rats. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12, 215 (2011).

Segredo-Morales, E. et al. Bone regeneration in osteoporosis by delivery BMP-2 and PRGF from tetronic-alginate composite thermogel. Int J Pharm 543(1–2), 160–168 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. In vivo validation of osteoinductivity and biocompatibility of BMP-2 enriched calcium phosphate cement alongside retrospective description of its clinical adverse events. Int J Implant Dent 10(1), 47 (2024).

Ishida, M., Fujioka, M., Takahashi, K. A., Arai, Y. & Kubo, T. Electromagnetic fields: A novel prophylaxis for steroid-induced osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(5), 1068–1073 (2008).

Ensrud, K. E., Crandall, C. J. Osteoporosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177(1):Itc1–itc16.

Tanaka, Y. & Ohira, T. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets for bone damage in rheumatoid arthritis, in particular the RANK-RANKL system. Curr Opin Pharmacol 40, 110–119 (2018).

Rahman, A. & Haider, M. F. A comprehensive review on glucocorticoids induced osteoporosis: A medication caused disease. Steroids 207, 109440 (2024).

Fan, Q., Zhan, X., Li, X., Zhao, J. & Chen, Y. Vanadate inhibits dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Ann Clin Lab Sci 45(2), 173–180 (2015).

Esmail, M. Y. et al. Effects of PEMF and glucocorticoids on proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts. Electromagn Biol Med 31(4), 375–381 (2012).

Adejuyigbe, B., Kallini, J., Chiou, D., Kallini, J. R. Osteoporosis: Molecular pathology, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(19).

Canalis, E., Mazziotti, G., Giustina, A. & Bilezikian, J. P. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos Int 18(10), 1319–1328 (2007).

Liu, H. F. et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields on postmenopausal osteoporosis in Southwest China: A randomized, active-controlled clinical trial. Bioelectromagnetics 34(4), 323–332 (2013).

Garland, D. E., Adkins, R. H., Matsuno, N. N. & Stewart, C. A. The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields on osteoporosis at the knee in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 22(4), 239–245 (1999).

Chen, C. Y., Rao, S. S., Yue, T., Tan, Y. J., Yin, H., Chen, L. J., Luo, M. J., Wang, Z., Wang, Y. Y., Hong, C. G. et al. Glucocorticoid-induced loss of beneficial gut bacterial extracellular vesicles is associated with the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8(15):eabg8335.

Tepper, O. M. et al. Electromagnetic fields increase in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis through endothelial release of FGF-2. Faseb J 18(11), 1231–1233 (2004).

Funding

This study was supported by the Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Tackling Program Joint Project (LHGJ20230041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuai Ding, Guangquan Zhang and Yanzheng Gao were involved in the design of the study. Shuai Ding and Guangquan Zhang carried out the histopathological and Bone mineral measurements. Zhiqiang Hou and Fuqiang Shao carried out the molecular analysis. Yanzheng Gao performed the statistical analysis. Shuai Ding and Guangquan Zhang drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental methods were reviewed as necessary and were authorized by the Animal Administration Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital. Clinical Trial Number: LHGJ20230041.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, S., Zhang, G., Gao, Y. et al. Investigating the preventive effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rats. Sci Rep 15, 2535 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86594-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86594-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Anti-osteoporosis Potential of Ananas comosus: An Herbal Phyto-Shield for the Silent Thief

Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation (2026)