Abstract

Although the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index has been established as a valuable predictor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cardiovascular mortality, there is limited research exploring its association with all-cause or CVD mortality specifically in adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without cardiovascular disease. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the TyG index and both all-cause and CVD mortality in this population within the United States. Our study recruited 1778 adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without cardiovascular disease from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2018. Mortality outcomes were determined by linking to National Death Index (NDI) records up to December 31, 2019. Cox regression modeling was employed to examine the association between the TyG index and mortality in this population. The nonlinear relationship between the TyG index and mortality was assessed using restricted cubic splines (RCS). Additionally, subgroup analyses and interaction tests were conducted to explore potential effect modifiers. A total of 1788 participants were included in the final cohort, with an average age of 49.61 ± 0.32 years. During a median follow-up of 7.92 years, the occurrence of 150 all-cause deaths and 33 CVD-related deaths were recorded. To investigate the independent association between the TyG index and the risks of all-cause and CVD mortality, three Cox regression models were developed. In Model 1, a significant positive association was observed between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.09–1.74). This association persisted in the minimally adjusted model (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13–1.83), which was adjusted for age, gender and race. Even after full adjustment, this positive association remained significant (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.36–2.70). We also found that the relationship between the TyG index and all-cause mortality was linear. Subgroup analyses revealed no significant interactions between the TyG index and the stratification variables. However, we did not observe a significant association between the TyG index and CVD mortality in this population. Our results suggested that a significantly positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality. The positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality was linear. We did not observe a significant association between the TyG index and CVD mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels, which in severe cases can lead to multi-system damage to blood vessels, heart, kidneys, retina, and nerves. In 2017, approximately 451 million adults worldwide were reported to have diabetes, with healthcare expenditures for these individuals estimated at $850 billion1. The global diabetic population is projected to reach 693 million by 20451.

Insulin resistance (IR) is a pathophysiological condition characterized by diminished sensitivity and responsiveness to insulin, ultimately leading to hyperglycemia2. IR is recognized as a causative factor and a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), regardless of whether they have diabetes3,4. However, there is no universally accepted method for assessing IR. The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and intravenous glucose tolerance test are two commonly used methods, but their invasive and costly nature limits their use in clinical practice5,6,7. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, calculated from fasting glucose (FPG) and fasting triglyceride (TG) levels, has emerged as a potential alternative for detecting IR. It is simple, convenient, accurate, and cost-effective, making it a viable option for assessing metabolic dysfunction8,9. Studies have shown that the TyG index is superior to the Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) in evaluating IR in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients10,11.

CVD morbidity and mortality are steadily rising globally, with the number of cardiovascular cases reported to have increased from 271 million in 1990 to 523 million in 201912. During the same period, cardiovascular-related deaths have surged from 12.1 million to 18.6 million12. The TyG index is recognized as a predictor of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes who have CVD13, even in younger patients with diabetes or prediabetes14. In younger diabetic patients, a U-shaped association has been observed between the TyG index and both all-cause and CVD mortality15.

Most of the diabetic patients in previous studies had baseline CVD, and few studies have evaluated the association between TyG index and CVD and all-cause mortality in adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without baseline CVD. Therefore, this study aimed to provide epidemiologic evidence of some association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality and CVD mortality in adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without baseline CVD.

Materials and methods

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing study designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population through complex multistage probability sampling. It encompasses both adults and children, offering a comprehensive overview of various health and dietary factors. The survey operates under ethical standards approved by The National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. NHANES collects extensive data, including demographic details, dietary habits, medical examination findings, laboratory results, and questionnaire responses. Participants provide written informed consent before their involvement. The datasets used in this study are publicly accessible on the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html).

Study population

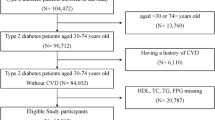

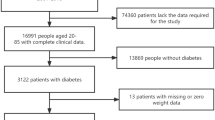

The data analyzed in this study were sourced from the NHANES database covering 2003 to 2018. The initial cohort consisted of 80,312 participants. After excluding individuals over 65 years old and under 20 years old (N = 46,718), those with missing TyG index data (N = 19,121), those without follow-up data (N = 0), those without diabetes (N = 11,825), and those with baseline CVD (N = 860), the final sample for analysis comprised 1,788 participants (Fig. 1).

Assessment of TyG index

The TyG index, used as the exposure variable in this study, was calculated using the formula: Ln [triglycerides (mg/dL) * fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2]. Triglyceride and fasting glucose levels were measured via enzymatic assays conducted on automatic biochemistry analyzers. Specifically, serum triglyceride levels were assessed using the Roche Modular P and Roche Cobas 6000 chemistry analyzers, while fasting plasma glucose levels were determined using a hexokinase-mediated reaction with the Roche/Hitachi Cobas C 501 chemistry analyzer. Participants were then divided into four quariles (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) based on TyG index, with the Q1 group serving as the reference group.

Assessment of mortality

Mortality status and causes of death for participants were determined by matching their records with the publicly available National Death Index files, with a repetition rate below 10% as of December 31, 2019 (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality.htm). Disease-specific deaths were classified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Cardiovascular deaths, including those from rheumatic heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, acute myocarditis, and heart failure, were identified with ICD-10 codes I00–I09, I11, I13, and I20–I51.

Assessment of covariates

Data on various demographic and health-related factors were collected through NHANES household interviews. This comprehensive dataset included information on alcohol use (yes/no), smoking status (never/former/current), and disease status (diabetes/hypertension). Diabetes (DM) was defined by either treatment or a medical diagnosis of hyperglycemia, with criteria including hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, or 2-h blood glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL16. Hypertension was defined as the use of antihypertensive medications, a medical diagnosis of hypertension, or three consecutive measurements of systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg17.

Demographic data collected included age, gender (female/male), race/ethnicity (Mexican American/Non-Hispanic Black/Non-Hispanic White/Others), education levels (less than 9th grade/9-11th grade/high school graduate/college graduate or above), the ratio of family income to poverty (PIR) (< 1/1–4/ > 4). Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by height squared (in meters). and categorized as normal weight (< 25 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Laboratory measurements included total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), fasting glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted following CDC guidelines, accounting for the complex probability sample design and deliberate oversampling in NHANES to ensure a representative population. Sample weights were applied to combine data from multiple survey cycles. Participants were categorized into four groups based on TyG index quartiles (Q1–Q4). Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Weighted one-way ANOVA was used for continuous variables, while the weighted chi-square test was used for categorical variables during descriptive analyses. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs for the association between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality. Three models were constructed to control for confounders: Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, and race; and Model 3 was adjusted for age, gender, race, education, PIR, BMI, hypertension, HDL-C, LDL-C, ALT, AST, HbA1c, alcohol use, and smoking status. Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data for covariates. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was used to explore the dose–response relationship between the TyG index and mortality risk. In cases of nonlinearity, the threshold value was determined by testing all possible values and selecting the one with the highest likelihood. Subgroup analyses of the TyG index’s association with all-cause and CVD mortality were performed, stratifying data by gender (male/female), BMI (normal weight/overweight/obesity), hypertension (yes/no), smoking status (never/former/current), and alcohol use (yes/no). These factors were also considered as potential effect modifiers. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2 (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation).

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study participants, stratified by quartiles of the TyG index. A total of 1788 participants were comprised in the final cohort, with an average age of 49.61 ± 0.32 years. Of these individuals, 49.03% were female and 50.70% were male. Additionally, 78.58% had completed high school or higher education, 14.90% reported a low household income, 63.16% were obese, 24.34% were overweight, 59.97% had hypertension, 74.76% consumed alcohol, and 22.10% were current smokers. The average TyG index among the participants was 9.25 ± 0.03, with quartile ranges of 5.65–8.73, 8.73–9.17, 9.17–9.72, and 9.72–12.84, respectively.

Significant differences were observed across the TyG index quartiles in in several variables, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, HDL-C, LDL-C, HbA1c%, ALT, AST, BMI, race, and alcohol consumption (all P < 0.05). More specifically, the highest TyG index quartile group had a greater proportion of Mexican Americans, a greater proportion of individuals classified as obese, a lower proportion of alcohol consumers, and more likely to have hyperlipidemia. Additionally, this group exhibited higher levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, LDL-C, HbA1c%, ALT, AST and BMI, and lower HDL-C levels. There were no significant differences among the quartiles in terms of age, gender, educational levels, PIR, smoking status, and hypertension (all P > 0.05). Compared to the subgroup of people aged 40 years or older, those under 40 years had higher BMI levels and were more likely to be current smokers and drinkers, but had a lower prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia (Supplemental Table S1).

Association of TyG index with all-cause mortality and CVD mortality.

The results in Table 2 illustrate the relationship between the TyG index quartiles and the all-cause mortality and CVD mortality in the whole population. During a median follow-up of 7.92 years, the occurrence of 150 all-cause deaths and 33 CVD-related deaths were recorded. Three Cox regression models were developed to investigate the independent association between the TyG index and the risks of all-cause and CVD mortality. In Model 1, a significant positive association was observed between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause mortality with an HR of 1.38 (95% CI 1.09–1.74). This association persisted in the minimally adjusted model, with an HR of 1.44 (95% CI 1.13–1.83), which was adjusted for age, gender, and race. This positive association remained significant even after full adjustment, with an HR of 1.91 (95% CI 1.36–2.70). Similar findings were noted when participants were categorized into quartiles based on the TyG index. In both Model 1 and Model 2, individuals in the highest TyG index quartile had a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest quartile (Model 1: Quartile 4: HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.03–3.28; Model 2: Quartile 4: HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.10–3.62). In the fully adjusted Model 3, the HR for all-cause mortality risk across Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 were 0.68 (95% CI 0.30–1.54), 1.27 (95% CI 0.61–2.61), and 2.58 (95% CI 1.39–4.77), respectively.

Furthermore, a positive association was observed between a higher TyG index and an increased risk of CVD mortality in both Model 1 (HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.01–2.53) and Model 2 (HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.03–2.57). However, this association became not significant in Model 3 after full adjustment (HR 1.45, 95% CI 0.56–3.77). When treating the TyG index into quartiles, the HR for CVD mortality from lowest to highest quartile, were 1.00 (reference), 0.26 (95% CI 0.07–1.01), 0.57 (95% CI 0.15–2.14), and 1.20 (95% CI 0.27–5.32), respectively.

RCS analysis

In our multivariate Cox regression analysis, we identified a potential nonlinear association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality. To further investigate this relationship, we performed a RCS analysis, as shown in Fig. 2. The RCS analysis revealed significant findings concerning the linear association between the TyG index, as continuous variables, and the adjusted risk of all-cause mortality in non-CVD patients with diabetes. Specifically, the overall test for association was significant (P overall = 0.0251), while the test for nonlinearity was not significant (P nonlinear = 0.1767).

Besides, in our study, we examined the population of adult individuals aged < 40 years and aged > 40 years (40–65 years) separately. The results revealed a linear relationship between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause mortality (P overall = 0.0486, P nonlinear = 0.1985) in adult individuals aged < 40 years. While in participants aged > 40 years (40–65 years), we did not observe a significant linear association between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause mortality (P overall = 0.2166, P nonlinear = 0.2971) (Supplemental Figure S1).

Subgroup analysis

To assess whether the association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality was consistent across different population subgroups and to identify potential variations, we conducted a subgroup analysis (Fig. 3). The analyses were stratified by gender, BMI, hypertension, smoking, and drinking status. A significantly positive relationship of the TyG index with all-cause mortality was detected in both male (HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.18–3.34) and female (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.14–4.60), overweight individuals (HR 6.18, 95% CI 2.73–13.96), those with hypertension (HR 2.51, 95% CI 1.56–4.06) and hyperlipidemia (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.49–3.60), current smokers (HR 3.09, 95% CI 1.53–6.22), never-smokers (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.37–4.83), and alcohol consumers (HR: 3.72, 95% CI 2.12–6.53). Importantly, no significant interactions between the TyG index and the stratification variables were observed in these analyses (all P for interaction > 0.05).

Discussion

In this study involving 1788 adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without CVD, we identified a positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality. We also found that the relationship between the TyG index and all-cause mortality was linear. Subgroup analyses revealed no significant interactions between the TyG index and the stratification variables. Additionally, our findings indicated a significant positive correlation between the TyG index and an increased risk of CVD mortality in the crude model and minimally adjusted model. However, the correlation between the TyG index and CVD mortality was no longer significant after full adjustment. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the TyG index served as a valuable marker for assessing the risk of all-cause mortality in adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without CVD, potentially aiding in the advancement of death prevention strategies.

Previous studies have highlighted the association between the TyG index and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events. For instance, research involving Korean adults found a significant positive correlation between the TyG index and coronary artery calcification18. A longitudinal study also demonstrated that individuals with a higher TyG index faced a significantly increased risk of subclinical atherosclerosis19. Moreover, a cohort study of 6,028 participants revealed a heightened risk of arterial stiffness among those with elevated TyG index levels20. The TyG index has proven to be a valuable predictor of coronary atherosclerotic plaque in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease, irrespective of their diabetic or hyperlipidemic status21. This link between the TyG index and atherosclerosis and coronary artery calcification emphasizes its strong association with CVD. For example, a higher TyG index has been linked to an increased likelihood of CVD in U.S. adults over 6022. Additionally, the TyG index has been significantly associated with an elevated risk of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and heart attack in nondiabetic patients23. TyG index has also been identified as a predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in individuals with early-onset coronary artery disease24.

Previous studies have explored the relationship between the TyG index and mortality across different patient groups and the general population. The TyG index has been significantly associated with both hospital and ICU all-cause mortality in ischemic stroke patients, highlighting its potential as a tool for identifying those at high risk25. TyG index was also found to be an independent predictor of mortality associated with hospitalization for critical cardiovascular disease26. A high TyG index has also been shown to be significantly associated with increased 28-day mortality in patients with critical sepsis27. Furthermore, a higher TyG index correlates with increased all-cause mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes and comorbid diabetes28. While most of these studies involved patients with underlying cardiovascular disease, our study excluded individuals with baseline CVD to further validate that the prognostic value of the TyG index in younger diabetic patients is independent of pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. The exact mechanism by which the TyG index relates to mortality and the progression of CVD remains unclear. One possible explanation is that the TyG index may serve as a reflection of IR levels, which could explain its role as a prognostic indicator of mortality in patients. As an early sign of insulin resistance, TyG-related indices may help to influence the proinflammatory status of participants and indicate susceptibility to disease severity and progression. IR is primarily manifested by decreased bioavailability of insulin, which leads to a decrease in the body’s ability to process and utilize glucose, resulting in impaired glucose homeostasis. IR can be mediated by an increase in vascular stiffness, as well as a decrease in the Nitric oxide bioavailability in vivo causes altered vascular structure and impaired function, which ultimately leads to endothelial dysfunction29,30. Endothelial dysfunction further exacerbates target organ damage, leading to marked vascular remodeling and progression of fibrosis.IR is also associated with other deleterious biological effects, such as increased systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to overproduction of reactive oxygen species and inactivation of the mitochondrial electron respiratory transport chain, resulting in vascular endothelial damage9,31,32. In addition to promoting thrombosis by increasing the expression of adhesion-inducing factors in platelets and thromboxane A2, IR can also lead to hypertrophy, injury, and fibrosis of cardiomyocytes by activating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system33,34,35. Overproduction of glycosylation products is also associated with smooth muscle cell proliferation, collagen deposition, and increased ventricular wall stiffness. All of these adverse stimuli contribute to vascular senescence and impairment of multiorgan function, ultimately leading to premature death. In addition, triglycerides are also associated with vascular dysfunction and increased resistance, which, as observed in some specific pathological conditions, may also further contribute to microvascular and myocardial injury, myocardial underperfusion, and the development of various cardiovascular events36,37. IR, in turn, is also closely associated with a range of metabolic disorders, such as lipotoxic insulin signaling, dyslipidemia, and adipose tissue dysfunction, which can further serve as important triggers for the progression of cardiovascular disease38,39,40,41.

The predictive value of TyG in patients with diabetes was unclear. A prospective study revealed a strong positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), particularly among older women42. Additionally, a higher TyG index was linked to an increased risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndromes, especially those over 80 years old28. In the U.S. population, a U-shaped relationship was observed between baseline TyG index and all-cause mortality in patients with both cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes or prediabetic CVD13. Another study identified a nonlinear association between the TyG index and CVD mortality risk in younger diabetic patients, noting a positive correlation when the TyG index exceeded 9.1615. Furthermore, a cohort study of 3,026 participants found no significant association between the TyG index and intensive care unit death or hospitalization death in patients with type 2 diabetes43. However, an increased incidence of diabetic nephropathy was observed in patients with TyG indices both below and above the threshold44. Most of the patients included in the above studies had CVD at baseline.

In our study, we identified a significant positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality in non-CVD patients with diabetes. However, our RCS analysis did not reveal a nonlinear relationship between the TyG index and all-cause mortality. Additionally, no significant correlation was observed between the TyG index and CVD mortality. In addition, our study revealed a linear relationship between the TyG index and the risk of all-cause mortality (P overall = 0.0486, P nonlinear = 0.1985) in adult individuals aged < 40 years. We hypothesize that the positive association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality in this population may be attributed to younger patients being less attentive to their blood glucose and triglyceride levels, and less likely to pursue intensive treatment compared to older patients. Previous research has shown that older patients with type 2 diabetes tend to have better control over glycemic and cardiovascular risk factors than their younger counterparts45. This difference may also be due to the fact that older adults often have more comorbidities and declining organ function, which may render traditional risk factors more predictive of outcomes than the TyG index.

This study has several strengths. Firstly, the study population was drawn from a nationally representative NHANES cohort, identified through a complex multistage probability sampling methodology, and included a substantial sample size of 1,788 patients with diabetes aged < 65 years without baseline CVD. Secondly, our study contributes to the existing research by examining the association between the TyG index and both all-cause and CVD mortality in patients with diabetes aged < 65 years without baseline CVD. Thirdly, stratification and sensitivity analyses were employed to further ensure the robustness and stability of the findings.

This study has several limitations that should not be overlooked. Firstly, the study population predominantly consisted of Americans, which may limit the generalizability of our findings due to differences in race, lifestyle, and residential environment. Further validation is needed to determine the applicability of our results to populations of different ethnicities and broader age ranges. Additionally, larger prospective studies are required to corroborate our findings and more clearly establish causality. Secondly, although we adjusted for potential confounders, we cannot entirely rule out the influence of unmeasured confounders. Furthermore, we lacked assessment of certain metabolic indices associated with IR, such as fasting plasma insulin levels. Thirdly, we were unable to analyze the dynamics of the TyG index over time because we only had a single baseline value for this index; thus, the impact of fluctuations in the TyG index on mortality remains unclear. Finally, the progression of diabetes is a dynamic process, but in this study, diabetes status was only assessed at baseline, which may potentially impact the study results. Previous studies have assessed the predictive value of the TyG index across different diabetes subtypes. For example, one study found the TyG index to be a useful tool for evaluating glycemic control in type 2 diabetes, with positive correlations to HbA1c and HOMA-IR46. In adults with type 1 diabetes, the TyG index is useful for assessing IR and has been identified as an independent risk factor for the development of diabetic nephropathy47. However, it is important to note that patients, particularly younger individuals with type 1 diabetes, may experience specific metabolic dysfunctions in plasma amino acid and TG levels48,49,50,51. These metabolic alterations could undermine the utility of the TyG index as a surrogate for IR, which is calculated using fasting glucose and TG levels, potentially leading to false-positive results. Furthermore, the NHANES study, which did not differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, limited our ability to stratify subgroups and assess the association in greater detail. There may also have been bias in the findings due to the inability to identify metabolic dysfunction in diabetic populations with comorbid appeals for plasma amino acid and TG levels. Despite these limitations, our study contributes valuable insights to the existing body of research. A broader study population is needed in the future to further elucidate these relationships.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings indicate that the TyG index may be a valuable tool for predicting the risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients aged < 65 years without CVD with comorbid diabetes. However, we did not observe a significant association between the TyG index and CVD mortality in this population. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further validate the relationship between the TyG index and CVD mortality risk in non-CVD patients with diabetes.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Cho, N. H. et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 138, 271–281 (2018).

Lebovitz, H. E. Insulin resistance: Definition and consequences. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 109(Suppl 2), S135-148 (2001).

Kosmas, C. E. et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Int Med Res 51(3), 3000605231164548 (2023).

Gast, K. B., Tjeerdema, N., Stijnen, T., Smit, J. W. & Dekkers, O. M. Insulin resistance and risk of incident cardiovascular events in adults without diabetes: Meta-analysis. PLoS One 7(12), e52036 (2012).

Wallace, T. M. & Matthews, D. R. The assessment of insulin resistance in man. Diabet Med 19(7), 527–534 (2002).

Minh, H. V. et al. Assessment of preferred methods to measure insulin resistance in Asian patients with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 23(3), 529–537 (2021).

Gutch, M., Kumar, S., Razi, S. M., Gupta, K. K. & Gupta, A. Assessment of insulin sensitivity/resistance. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 19(1), 160–164 (2015).

Hong, S., Han, K. & Park, C. Y. The triglyceride glucose index is a simple and low-cost marker associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A population-based study. BMC Med 18(1), 361 (2020).

Tao, L. C., Xu, J. N., Wang, T. T., Hua, F. & Li, J. J. Triglyceride-glucose index as a marker in cardiovascular diseases: Landscape and limitations. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 68 (2022).

Vasques, A. C. et al. TyG index performs better than HOMA in a Brazilian population: a hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 93(3), e98–e100 (2011).

Lee, S. H. et al. Predicting the development of diabetes using the product of triglycerides and glucose: The Chungju Metabolic Disease Cohort (CMC) study. PLoS One 9(2), e90430 (2014).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global Burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 76(25), 2982–3021 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Xiao, S., Jiao, X. & Shen, Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: Evidence from NHANES 2001–2018. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 279 (2023).

Liu, C. & Liang, D. The association between the triglyceride-glucose index and the risk of cardiovascular disease in US population aged ≤ 65 years with prediabetes or diabetes: A population-based study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 23(1), 168 (2024).

Liu, C., Liang, D., Xiao, K. & Xie, L. Association between the triglyceride-glucose index and all-cause and CVD mortality in the young population with diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 23(1), 171 (2024).

Menke, A., Casagrande, S., Geiss, L. & Cowie, C. C. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 314(10), 1021–1029 (2015).

Fryar, C. D., Ostchega, Y., Hales, C. M., Zhang, G. & Kruszon-Moran, D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief 289, 1–8 (2017).

Park, K. et al. Elevated TyG index predicts progression of coronary artery calcification. Diabetes Care 42(8), 1569–1573 (2019).

Lu, Y. W. et al. Gender difference in the association between TyG index and subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the I-Lan Longitudinal Aging Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20(1), 206 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of arterial stiffness: A cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20(1), 146 (2021).

Li, J. et al. The triglyceride-glucose index is associated with atherosclerosis in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease, regardless of diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 224 (2023).

Liang D, Liu C, Wang Y. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and the likelihood of cardiovascular disease in the U.S. population of older adults aged ≥ 60 years: A population-based study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2024: 23(1): 151.

Sawaf, B., Swed, S., Alibrahim, H., Bohsas, H., Dave, T., Nasif, M. N., et al. Triglyceride-glucose index as predictor for hypertension, CHD and STROKE Risk among Non-Diabetic Patients: A NHANES Cross-Sectional Study 2001–2020. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health 2024.

Wu, Z. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index in the prediction of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with premature coronary artery disease: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 142 (2022).

Cai, W. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with ischemic stroke: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 138 (2023).

Zhai, G., Wang, J., Liu, Y. & Zhou, Y. Triglyceride-glucose index linked to in-hospital mortality in critically Ill patients with heart disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med 23(8), 263 (2022).

Zheng, R. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22(1), 307 (2023).

Shen, J. et al. Triglyceride glucose index predicts all-cause mortality in oldest-old patients with acute coronary syndrome and diabetes mellitus. BMC Geriatr 23(1), 78 (2023).

Khan, S. H. et al. Metabolic clustering of risk factors: Evaluation of Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) for evaluation of insulin resistance. Diabetol Metab Syndr 10, 74 (2018).

Molina, M. N., Ferder, L. & Manucha, W. Emerging role of nitric oxide and heat shock proteins in insulin resistance. Curr Hypertens Rep 18(1), 1 (2016).

Adeva-Andany, M. M., Ameneiros-Rodríguez, E., Fernández-Fernández, C., Domínguez-Montero, A. & Funcasta-Calderón, R. Insulin resistance is associated with subclinical vascular disease in humans. World J Diabetes 10(2), 63–77 (2019).

Hill, M. A. et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism 119, 154766 (2021).

Calles-Escandon, J., Mirza, S. A., Sobel, B. E. & Schneider, D. J. Induction of hyperinsulinemia combined with hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia increases plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in blood in normal human subjects. Diabetes 47(2), 290–293 (1998).

Jia, G., Hill, M. A. & Sowers, J. R. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: An update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res 122(4), 624–638 (2018).

Lambie, M. et al. Insulin resistance in cardiovascular disease, uremia, and peritoneal dialysis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 32(9), 721–730 (2021).

Baracchi, A. et al. When pregnancy-associated hypertriglyceridemia goes above and beyond the risk of pancreatitis. Intern Emerg Med 19(2), 477–481 (2024).

Takaeko, Y. et al. Lower triglyceride levels are associated with better endothelial function. J Clin Lipidol 15(3), 500–511 (2021).

Ritchie, S. A. & Connell, J. M. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 17(4), 319–326 (2007).

Vergès, B. Pathophysiology of diabetic dyslipidaemia: where are we?. Diabetologia 58(5), 886–899 (2015).

Xu, H. et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112(12), 1821–1830 (2003).

Yang, Q., Vijayakumar, A. & Kahn, B. B. Metabolites as regulators of insulin sensitivity and metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19(10), 654–672 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is strongly associated with all-cause mortality in elderly females with diabetic foot ulcers: A 9-year follow-up study. Int Wound J 21(1), e14344 (2024).

Liao, Y. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index linked to all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: A cohort of 3026 patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1), 128 (2022).

Shang, J. et al. The triglyceride glucose index can predict newly diagnosed biopsy-proven diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: A nested case control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(46), e17995 (2019).

Barrot-de la Puente, J., Mata-Cases, M., Franch-Nadal, J., Mundet-Tudurí, X., Casellas, A., Fernandez-Real, J. M., et al. Older type 2 diabetic patients are more likely to achieve glycaemic and cardiovascular risk factors targets than younger patients: analysis of a primary care database. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015: 69(12): 1486–1495.

Selvi, N. M. K. et al. Association of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) with HbA1c and insulin resistance in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Maedica (Bucur) 16(3), 375–381 (2021).

Lei, M. et al. Correlation between triglyceride-glucose index and diabetic kidney disease risk in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr 16(1), 239 (2024).

Mook-Kanamori, D. O. et al. Increased amino acids levels and the risk of developing of hypertriglyceridemia in a 7-year follow-up. J Endocrinol Invest 37(4), 369–374 (2014).

Hendrix, G. et al. Catabolism of fats and branched-chain amino acids in children with Type 1 diabetes: Association with glycaemic control and total daily insulin dose. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 6(6), e448 (2023).

Svanberg, E. et al. The role of glucose, long-chain triglycerides and amino acids for promotion of amino acid balance across peripheral tissues in man. Clin Physiol 19(4), 311–320 (1999).

Melena, I. et al. Aminoaciduria and metabolic dysregulation during diabetic ketoacidosis: Results from the diabetic kidney alarm (DKA) study. J Diabetes Complications 36(6), 108203 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and the participants of the NHANES study for their valuable contributions.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (Grant No. 82100096), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2303200), and The First batch of Key Disciplines On Public Health in Chongqing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CL, DL, GAX and XBZ conceived and designed the study, acquired the data and drafted the manuscript. KX and LXX reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C., Liang, D., Xiang, G. et al. Association of the triglyceride glucose index with all cause and CVD mortality in the adults with diabetes aged < 65 years without cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 15, 2745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86612-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86612-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combining triglyceride‑glucose index and novel anthropometric measures to predict mortality risk in patients with T2DM: a prospective cohort study

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2026)

-

Anthropometric indices and mortality in postmenopausal women: NHANES 1999–2018 evidence

BMC Women's Health (2025)

-

The association between triglyceride-glucose index and all-cause/cardiovascular mortality in patients with different glucose metabolism statuses

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2025)