Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) scores and bone mineral density (BMD) in adults aged 20–59 years. This cross-sectional analysis employed nationally representative data from NHANES 2011–2018. Weighted multiple linear regression models were applied to assess the association between LE8 scores and varying levels of cardiovascular health (CVH) with BMD. Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate differences in the impact of LE8 scores on BMD across age groups, genders, races, socioeconomic statuses, and BMI categories. The study included 2159 participants. After adjusting for all covariates, LE8 scores demonstrated a significant positive linear association with lumbar spine BMD, thoracic spine BMD, trunk BMD, and total BMD. Individuals in the medium and high CVH groups exhibited higher BMD compared to those in the low CVH group. Subgroup analyses indicated that the association was more evident in participants aged 20–35 years and among those with normal BMI. In females, thoracic spine BMD appeared particularly sensitive to changes in LE8 scores. This study identifies a positive linear relationship between LE8 scores and BMD. Higher CVH scores were linked to greater BMD in adults aged 20–59 years. These findings highlight the importance of adopting comprehensive health strategies, suggesting that improving CVH may contribute to maintaining bone density and supporting skeletal health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a widespread health concern characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD), significantly impacting middle-aged and elderly populations1. According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation, over 30% of women and 20% of men above the age of 50 globally are at risk of fractures due to reduced bone mass2. The pathogenesis and etiology of osteoporosis are multifaceted, involving numerous risk factors3,4,5. Emerging evidence indicates that individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease face a higher risk of developing osteoporosis6. Shared risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, are associated with both cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis7,8,9, suggesting a possible physiological connection between these conditions.

In 2022, the American Heart Association (AHA) introduced an updated quantitative tool for assessing cardiovascular health (CVH), termed Life’s Essential 8 (LE8)10. Studies have consistently shown that individuals with higher LE8 scores tend to lead healthier lifestyles and exhibit a notably reduced risk of cardiovascular disease11. Recent investigations have highlighted the utility of LE8 scores in lowering the risk of kidney stones, forecasting stroke risk, and evaluating arterial stiffness12,13,14. However, the association between LE8 and BMD remains insufficiently explored. Some evidence suggests that a healthy lifestyle may alleviate inflammation and oxidative stress, potentially improving BMD15. Examining the relationship between LE8 and BMD holds both theoretical and practical significance. Understanding this connection may deepen insights into the mechanisms underlying osteoporosis. Moreover, for adults aged 20–59, addressing LE8-related lifestyle and behavioral factors could provide novel strategies for indicating and managing osteoporosis. This study seeks to explore the potential relationship between LE8 and BMD, aiming to offer new perspectives and approaches for the comprehensive treatment of osteoporosis.

Materials and methods

Study population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a cross-sectional study supported by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the civilian population in the United States. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

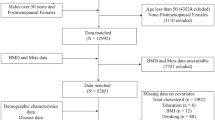

This study analyzed data from the 2011–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), encompassing 39,156 participants. A strict exclusion process was applied based on predefined criteria. The following individuals were excluded: 24,222 participants younger than 20 or older than 59 years; 992 postmenopausal women; 1753 individuals with chronic diseases linked to abnormal bone metabolism; 9201 participants with missing data on LE8 variables or BMD; 270 participants with a history of fractures (n = 162), osteoporosis (n = 12), or a family history of osteoporosis (n = 96); and 559 individuals with incomplete covariate data. The final analysis sample included 2159 participants aged 20–59 years (Fig. 1).

Measurement of the LE8

The LE8 includes four health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep health) and four health factors (body mass index (BMI), blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure)15. The diet metric was assessed using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 201516,17. Dietary intake data obtained from two 24 h dietary recalls were integrated with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) food patterns equivalents data to derive the HEI-2015 scores (Supplementary File: Table S1). Information on physical activity, nicotine exposure, sleep health, diabetes status, and medication history was collected through standardized questionnaires. Height and weight measurements obtained during physical examinations were used to calculate BMI, defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Laboratory data were utilized to determine blood lipids and blood glucose levels. Blood pressure was measured at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) after participants rested quietly for 5 min, with the average of three consecutive readings recorded for analysis. Detailed algorithms for calculating each LE8 component score have been previously documented (Supplementary File: Table S2).

Each LE8 component score ranges from 0 to 100, and the overall LE8 score is calculated as the unweighted average of these eight component scores18. Based on the AHA guidelines, a high CVH score (80–100) reflects optimal CVH, associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease. A moderate CVH score (50–79) indicates a moderate risk, signaling the need for attention to and improvement in health behaviors to avert cardiovascular events. A low CVH score (0–49) denotes poor CVH, associated with a high cardiovascular disease risk19.

Measurement of the BMD

In this study, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements were performed using the Hologic QDR 4500 A fan-beam densitometer on all eligible participants20. DXA is internationally recognized as an essential screening tool for assessing the risk of osteoporotic fractures. Scans were conducted by trained and certified radiologic technicians, providing BMD data for the head, lumbar spine, thoracic spine, trunk (including the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, ribs, and pelvis), and total body. BMD data from these sites were collected between 2011 and 2018.

Definition of covariates

Covariates included multiple factors previously shown or hypothesized to be associated with CVH or BMD. Demographic data comprised age, gender, race, education level, and the poverty income ratio (PIR). Information on alcohol consumption was obtained from the dietary interview individual food file21. Alcohol consumption was categorized based on questionnaire responses into the following groups: 1–5 times per month, 5–10 times per month, more than 10 times per month, and never (defined as having never consumed 12 alcoholic drinks in a lifetime). Smoking history was obtained through questionnaires and categorized as never smokers (having smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), former smokers (having smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but not currently smoking), and current smokers (having smoked more than 100 cigarettes and currently smoking). The diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes history was based on a combination of clinical measurements, medication records, and self-reported information. Hypertension was defined as an average of three blood pressure measurements with systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, a prior diagnosis by a physician, or the use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%, fasting blood glucose 126 mg/dL, a physician’s diagnosis, or the use of antidiabetic medications or insulin therapy. Laboratory data included measurements of vitamin D intake, serum creatinine, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and serum calcium. All serological measurements were conducted in certified laboratories using standardized and validated analytical methods.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2). To account for the complex sampling design of NHANES, the appropriate sampling weight (WTMEC 2YR) was applied, ensuring national representativeness of the data. For normally distributed continuous variables, data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), and comparisons between groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), with the Kruskal–Wallis test used for group comparisons. Categorical variables were reported as frequency (%), and inter-group differences were assessed using the χ2 test to examine variations in characteristics across low, medium, and high CVH groups. Weighted linear regression analysis was employed to evaluate the relationship between LE8 scores and BMD. Three models were constructed: Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, and race; and Model 3 included adjustments for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, alcohol consumption, frequency of alcohol intake, vitamin D intake, ALT, AST, serum creatinine, and serum calcium. To further assess potential non-linear relationships between LE8 scores and BMD, smoothing curve fitting analysis was conducted. Subgroup analyses were also carried out to explore the association between LE8 scores and BMD across various strata, including age, race, education level, BMI, and PIR. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2159 participants were included in this study, with 52.15% being male and an average age of 36.61 ± 10.95 years. Compared to the low CVH group, participants in the high CVH group were younger, predominantly female, non-Hispanic white, with higher levels of education and better socioeconomic status. They also had lower alcohol consumption and a higher proportion of never smokers. Furthermore, although ALT and AST levels remained within the normal range, they were significantly higher in the high CVH group compared to the low CVH group, while BMI was significantly lower in the high CVH group. As CVH scores increased, both lumbar spine BMD and trunk BMD showed an upward trend. Regarding comorbidities, the high CVH group had a significantly higher proportion of individuals without hypertension and diabetes (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Association between LE8 and BMD

Weighted multivariate linear regression models were used to examine the relationship between LE8 scores, different CVH groups, and BMD. In the fully adjusted model, LE8 scores showed a positive association with lumbar spine BMD (β = 0.016, 95% CI 0.009, 0.022, P < 0.001), thoracic spine BMD (β = 0.009, 95% CI 0.004, 0.014, P < 0.001), trunk BMD (β = 0.013, 95% CI 0.009, 0.018, P < 0.001), and total BMD (β = 0.010, 95% CI 0.006, 0.015, P < 0.001). These associations remained significant across all CVH groups.

Compared to participants in the low CVH group, those in the high CVH group exhibited increases of 0.042 g/cm2 in lumbar spine BMD, 0.033 g/cm2 in thoracic spine BMD, 0.046 g/cm2 in trunk BMD, and 0.049 g/cm2 in total BMD. Smooth curve fitting analyses further demonstrated a positive linear correlation between LE8 scores and BMD at the lumbar spine, thoracic spine, trunk, and total body levels (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Results of subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis revealed significant variations in the relationship between LE8 scores and BMD at four anatomical sites across age and BMI categories (P < 0.05). Participants aged 20–34 exhibited the most pronounced increases in BMD compared to other age groups. For every 10-point increase in LE8 scores, lumbar spine BMD increased by 0.022 g/cm2, thoracic spine BMD by 0.012 g/cm2, trunk BMD by 0.017 g/cm2, and total BMD by 0.013 g/cm2 in this age group (P < 0.05). In BMI-specific analyses, individuals within the normal BMI range (18.5–24.9) experienced significantly greater increases in BMD compared to those in the underweight and overweight groups. For every 10-point increase in LE8 scores, lumbar spine BMD increased by 0.020 g/cm2, thoracic spine BMD by 0.014 g/cm2, trunk BMD by 0.021 g/cm2, and total BMD by 0.018 g/cm2 in the normal BMI group (P < 0.05). No significant association was observed between LE8 scores and BMD in the underweight and overweight groups. Additionally, the study identified a significant positive association between LE8 scores and thoracic spine BMD among females (β = 0.011, 95% CI 0.002, 0.019, P < 0.001), while no significant association was observed in males (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study demonstrates a significant positive relationship between the LE8 score and BMD at the lumbar spine, thoracic spine, trunk, and total body. Furthermore, this correlation is more pronounced among individuals with higher levels of CVH. Subgroup analyses and interaction tests revealed that the association varies across different age groups, genders, and BMI categories. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining healthy behaviors and factors to support CVH, which may play a vital role in promoting healthy bone metabolism.

Previous studies have suggested an association between cardiovascular disease and BMD22,23. Both conditions share several common influencing factors that affect BMD to varying extents. For example, adherence to a balanced diet, regular physical activity, smoking cessation, maintaining a consistent sleep pattern, and achieving a healthy BMI are widely recognized as protective measures against osteoporosis and effective strategies to prevent BMD loss24,25,26,27,28,29,30. This study integrates a diverse range of CVH indicators into a unified LE8 score, providing a more comprehensive perspective on how overall CVH impacts BMD. Emerging evidence suggests a positive association between the LE8 score and femoral neck BMD, with a 10-point increase in the LE8 score linked to a 0.04 g/cm2 increase in femoral neck BMD31. However, Tang et al. observed a more complex relationship between the LE8 score, BMD, and osteoporosis risk in older adults. In their unadjusted model, the LE8 score was negatively associated with BMD, but this shifted to a positive relationship after adjusting for covariates32. This finding contrasts with the results of the current study, which identified a positive correlation between the LE8 score and BMD even in unadjusted models. A possible explanation for this discrepancy lies in the focus of Tang et al.’s study on middle-aged and older populations. These individuals are more likely to be affected by unmodifiable factors, such as medication use, chronic diseases, and long-standing dietary habits. Such factors may reduce the positive influence of healthy behaviors on BMD, thereby altering the observed association between the LE8 score and BMD.

The mechanisms underlying the relationship between the LE 8 score and BMD can be explained through the complex interplay of various lifestyle and physiological factors included in the LE 8 framework. These factors promote cardiovascular and bone health through distinct yet interconnected mechanisms. For example, the DASH diet, characterized by high calcium and low sodium content, helps optimize calcium metabolism, thereby supporting bone growth and maintenance33. Physical activity stimulates bone remodeling through mechanical loading, which enhances bone density34. Conversely, unhealthy behaviors such as smoking inhibit calcium absorption and disrupt hormonal balance, leading to bone deterioration29. Poor sleep quality can affect hormonal regulation, which is closely linked to lower BMD and an increased risk of fractures35. Elevated cholesterol levels are associated with increased bone resorption, potentially through inflammatory pathways36. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance not only impair bone quality but also suppress bone formation, highlighting the importance of diabetes management for bone health. Similarly, hypertension interferes with calcium and phosphate metabolism, emphasizing the critical role of blood pressure control in maintaining bone density37. The impact of BMI on BMD varies across different levels. Individuals within the normal BMI range typically have better nutritional status, lower levels of inflammation, and appropriate mechanical loading, which contribute to bone health. However, excessively high or low BMI levels may have adverse effects on BMD38. This finding is consistent with the results of this study’s subgroup analysis, which showed a significant positive correlation between LE8 scores and BMD in individuals with a normal BMI range (18.5–24.9), while no such association was observed in underweight or overweight populations39.

Additionally, this study found that the relationship between LE8 scores and BMD differed significantly across age groups and genders. The increase in BMD was more pronounced in younger individuals (aged 20–34 years) compared to other age groups. This may be attributed to more active bone metabolism, greater capacity for bone growth and repair, and relatively stable hormone levels in this demographic. Furthermore, healthy behaviors such as maintaining a balanced diet and engaging in regular physical activity are more likely to have a positive impact on BMD during this stage of life40,41. The study also observed that thoracic spine BMD in women appeared to be more sensitive to changes in the LE8 score. This sensitivity could be due to men having a higher baseline thoracic spine BMD and the influence of hormonal factors specific to women, such as estrogen. Research indicates that fluctuations in estrogen levels can significantly affect women’s BMD42. Healthy behaviors reflected in the LE8 score, including adequate physical activity and proper nutritional intake, may contribute to maintaining or increasing estrogen levels, which in turn supports BMD43. Interestingly, this study did not identify a significant relationship between LE8 scores and head BMD. This outcome might be explained by the unique characteristics of cranial bone within the skeletal system. The methods used to measure cranial BMD and its clinical implications differ from those applied to other skeletal sites. Factors such as hair and skin thickness, cranial shape, and density distribution can affect measurement accuracy, potentially reducing the statistical significance of the findings44.

This study highlights a significant positive association between the LE8 score and BMD, with the relationship being more pronounced among individuals with higher CVH. By consolidating CVH indicators into a single composite score, the study not only advances the understanding of the interaction between CVH and bone metabolism but also identifies variations in this relationship across age, gender, and BMI groups. These findings provide a scientific basis for the development of personalized osteoporosis prevention strategies, emphasizing the vital role of healthy behaviors in maintaining BMD. The novelty of this study lies in its systematic examination of the association between the LE8 score, a comprehensive CVH indicator, and BMD among individuals aged 20–59. The results suggest that the LE8 score, as a simple and practical tool, could serve as an effective indicator for assessing bone health risks in clinical practice. Furthermore, the findings reveal that improving CVH not only reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease but also has a positive impact on BMD maintenance. Promoting healthy behaviors to optimize CVH may therefore represent a promising strategy for lowering the prevalence of osteoporosis and improving bone health.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. While most existing research on the relationship between the LE 8 score and BMD has focused on older populations, this study examines this relationship in younger and middle-aged adults. Additionally, the use of nationally representative data enables a comprehensive investigation of the association between the LE 8 score and BMD in the U.S. adult population. Subgroup analyses and interaction tests provide insights into the variations of this relationship across age, gender, and BMI groups, supporting the development of personalized intervention strategies.

However, some limitations should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes the establishment of causal relationships. Some self-reported data may introduce biases. Despite controlling for various covariates, residual confounding factors cannot be entirely ruled out. Moreover, due to database constraints, data on hip and femoral neck BMD were collected only during the 2017–2018 cycle, resulting in a smaller sample size, which was excluded from this study. Future research should explore the association between the LE 8 score and BMD in these skeletal sites. Additionally, the exclusion of postmenopausal women means the findings may not be generalizable to this critical population. Future studies should expand the sample size, include postmenopausal women for separate analysis, and compare them with other groups to reveal differences across physiological stages.

Conclusion

This study identified a linear positive relationship between the LE8 score and BMD in individuals aged 20–59, with significant variations across age, gender, and BMI groups. These findings suggest that CVH plays an important role in bone metabolism and may help reduce the risk of osteoporosis. Clinically, adopting lifestyle changes or medical interventions to improve CVH could have beneficial effects on bone health. Healthcare providers are encouraged to incorporate CVH assessments when evaluating osteoporosis risk and to explore strategies that address both cardiovascular and bone health to enhance overall patient care.

Data availability

Data availability statementThe analysis in this study utilized publicly available datasets from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for the years 2011-2018. These datasets are accessible at the following URL: (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

References

Ensrud, K. E., Crandall, C. J. Osteoporosis Ann. Intern. Med. 167, ITC17–ITC32. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC201708010 (2017).

Wright, N. C. et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J. Bone Min. Res. 29, 2520–2526. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2269 (2014).

Curry, S. J. et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 319, 2521–2531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.7498 (2018).

Liu, J., Gao, Z. & Liu, X. Mitochondrial dysfunction and therapeutic perspectives in osteoporosis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1325317. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1325317 (2024).

Lobo, R. A. & Gompel, A. Management of menopause: a view towards prevention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10, 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00269-2 (2022).

Tang, H. et al. The different correlations between obesity and osteoporosis after adjustment of static mechanical loading from weight and fat free mass. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 21, 351–357 (2021).

Erdélyi, A. et al. The importance of nutrition in menopause and perimenopause—a review. Nutrients 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010027 (2023).

Fuggle, N. R. et al. Assessment of cardiovascular safety of anti-osteoporosis drugs. Drugs 80, 1537–1552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01364-2 (2020).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 146, e18–e43. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078 (2022).

Ma, H. et al. Cardiovascular health and life expectancy among adults in the United States. Circulation 147, 1137–1146. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062457 (2023).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults and children using the American Heart Association’s new Life’s essential 8 metrics: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2013 through 2018. Circulation 146, 822–835. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060911 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Life’s essential 8 and risk of stroke: a prospective community-based study. Stroke 54, 2369–2379. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.042525 (2023).

Du, Y. Z. et al. Association between kidney stones and Life’s essential 8: a population-based study. World J. Urol. 42, 274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-024-04994-3 (2024).

Anupama, D. S. et al. Effect of lifestyle modification intervention programme on bone mineral density among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 23, 387–393. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.1.2023.010 (2023).

Qu, L. et al. Association of inflammatory markers with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or osteopenia. BMC Womens Health. 23, 487. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02631-6 (2023).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 1591–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.021 (2018).

National Cancer Institute. HEI Scoring Algorithm. Accessed. May. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/hei-scoring-method.html (2024).

Sun, J. et al. Association of the American Heart Association’s new Life’s essential 8 with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 21, 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02824-8 (2023).

Faronese, N. et al. Relationship between low bone mineral density and fractures with incident cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bone Min. Res. 32, 1126–1135. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3089 (2017).

Baran, D. T. et al. Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis: guidelines for the utilization of bone densitometry. Calcif. Tissue Int. 61, 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002239900362 (1997).

Alcohol Research. Current reviews Editorial Staff. Drinking patterns and their definitions. Alcohol Res. 39, 17–18 (2018).

Yang, Y. & Huang, Y. Association between bone mineral density and cardiovascular disease in older adults. Front. Public. Health. 23, 11:1103403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1103403 (2023 Jun).

Park, J. et al. Prognostic value of lower bone mineral density in predicting adverse cardiovascular disease in Asian women. Heart 107, 1040–1046. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318764 (2021).

Fan, Y., Ni, S. & Zhang, H. Association between Healthy Eating Index-2015 total and component food scores with osteoporosis in middle-aged and older americans: a cross-sectional study with U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-021-06247-0 (2022).

Ochs-Balcom, H. M. et al. Short sleep is associated with low bone mineral density and osteoporosis in the women’s Health Initiative. J. Bone Min. Res. 35, 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3879 (2020).

Liu, X., Chen, F., Liu, L. & Zhang, Q. Prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01260-828 (2023).

Nethander, M. et al. Assessment of the genetic and clinical determinants of hip fracture risk: genome-wide association and mendelian randomization study. Cell. Rep. Med. 3, 100776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100776 (2022).

Li, S. & Zeng, M. The association between dietary inflammation index and bone mineral density: results from the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Ren. Fail. 45, 2209200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2023.2209200 (2023).

Hou, W. et al. Associations between smoke exposure and osteoporosis or osteopenia in a US NHANES population of elderly individuals. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1074574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1074574 (2023).

Hejazi, K., Askari, R. & Hofmeister, M. Effects of physical exercise on bone mineral density in older postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Osteoporos. 17, 102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01140-7 (2022).

Xie, R., Huang, X., Zhang, Y., Liu, Q. & Liu, M. High low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are associated with osteoporosis among adults 20–59 years of age. Int. J. Gen. Med. 15, 2261–2270. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S353531 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. Life’s essential 8 and osteoporosis in adults aged 50 years or older: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch. Osteoporos. 19, 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-024-01368-5 (2024).

Zhai, X. L. et al. The association between dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet and bone mineral density in US adults: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011–2018). Sci. Rep. 13, 23043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50423-7 (2023).

Ji, J. et al. Association between physical activity and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study from the NHANES 2007–2018. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 501. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03976-2 (2023).

Swanson, C. M. Sleep disruptions and bone health: what do we know so far? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 28, 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000639 (2021).

Cherny, S. S., Freidin, M. B., Williams, F. M. K. & Livshits, G. The analysis of causal relationships between blood lipid levels and BMD. PLoS One. 14, e0212464. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212464 (2019).

Yang, Y. & Huang, Y. Association between bone mineral density and cardiovascular disease in older adults. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1103403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1103403 (2023).

Kervin, T. & Thangarajh, M. The relationship between bone mineral density and cardiovascular function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Curr. 10 https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.md.ee7ac0ec8c19a47b114737f9c2714779 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Associations between weight-adjusted waist index and bone mineral density: results of a nationwide survey. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23, 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01418-y (2023).

Julian, V. et al. Bone response to high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training in adolescents with obesity. Obes. Facts. 15, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519271 (2022).

Denova-Gutiérrez, E., Méndez-Sánchez, L., Muñoz-Aguirre, P., Tucker, K. L. & Clark, P. Dietary patterns, bone mineral density, and risk of fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 10, 1922. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121922 (2018).

Simion, G., Eckardt, N., Ullrich, B. W., Senft, C. & Schwarz, F. Bone density of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine measured using Hounsfield units of computed tomography—results of 4350 vertebras. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07324-1 (2024).

Turcotte, A. F. et al. Association between obesity and risk of fracture, bone mineral density and bone quality in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 16, e0252487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252487 (2021).

El Miedany, Y. Best practice recommendations for DXA scans and reports. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87950-1_10 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. conceptualized the study. Z.X., Z.C., Y.G. and W.P. conducted data collection and analysis. Y.C., Z.X., and Z.C. drafted the manuscript. X.Z., Y.G., and P.W. provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The NCHS Ethics Review Board reviewed and approved this study. All patients/participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Y., Xu, Z., Cui, Z. et al. Association between life’s essential 8 and bone mineral density among adults aged 20–59 years. Sci Rep 15, 2664 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86749-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86749-7