Abstract

Background Intrusive “thoughts” represent undesirable cognitive activity that can cause distress, and occurs in individuals with and without psychological disorders. In order to deal with unwanted intrusive thoughts, individuals might consciously attempt to halt the flow of these cognitions through suppression or unconsciously avoid them automatically through repression. This study aimed to psychometrically evaluate and validate a translation of the Emotional and Behavioral Reaction to Intrusions Questionnaire (EBRIQ) in Arabic, for adults who speak the language. Methods The snowball sampling technique was used to recruit adults (n = 755) from five Arab countries (Lebanon, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Jordan, and Kuwait), who completed the Arabic EBRIQ. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the factor structure of the EBRIQ. Results A total of 755 participants completed the survey, with a mean age of 21.89 ± 4.18 years and 77.5% females. CFA indicated a modest fit for the one-factor model. Internal reliability was excellent (ω = 0.96; α = 0.96). No significant difference was found in terms of EBRIQ scores between males (M = 10.37, SD = 7.80) and females (M = 10.52, SD = 7.99) in the total sample, t(753) = − 0.22, p = .830. The highest EBRIQ scores were found in Jordanian participants (12.55 ± 6.94), followed by Emirati (12.23 ± 8.20), Lebanese (11.12 ± 7.69), Egyptian (8.96 ± 8.05) and Kuwaiti (8.20 ± 7.75) participants, F(4, 750) = 10.36, p < .001. Conclusion This study suggests that our Arabic translation of the EBRIQ is psychometrically proven to be reliable for use in Lebanon, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Jordan, and Kuwait. This validated tool will allow researchers and practitioners to assess emotions and behaviors related to intrusive thoughts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intrusive thoughts represent undesirable cognitive activity that can cause distress, and occurs in individuals with and without psychological disorders1. Experiencing frequent intrusive thoughts has been connected to psychopathology including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)2, illness anxiety disorder (IAD)3and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)4.

In nonclinical individuals, intrusive thoughts were related to maladaptive emotions and behaviors such as impulsivity5, potential self-harm6and depressive mood7. A recent review found that Middle Eastern individuals diagnosed with OCD can experience more intense intrusive thoughts, especially ones that are associated with religion8. In Jordan specifically, intrusive thoughts related to hygiene among those diagnosed with OCD were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic9. Similarly, individuals with diagnosed OCD in Gulf countries, including United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kuwait, experienced an increase in intrusive thoughts during COVID-1910. Among Egyptian individuals, those who exhibited higher levels of OCD had a higher probability of experiencing intrusive thoughts related to suicidal ideation11.

In order to deal with unwanted intrusive thoughts, individuals might consciously attempt to halt the flow of these cognitions through suppression or unconsciously avoid them automatically through repression12. Suppression of intrusive thoughts was previously assessed by the White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI), a self-report measure meant to evaluate the incidence of intentional avoidance of spontaneous unwanted thinking13. Briefly after, higher WBSI scores were found to be correlated with emotional vulnerability14. Yet, the WBSI did not consider the emotional and behavioral reactions to intrusive thoughts, but focused on coping strategies. As a result, the Emotional and Behavioral Reactions to Intrusions Questionnaire (EBRIQ) was developed, consisting of 7 self-rated items relating to feelings and actions associated with intrusive thoughts15. In the original scale, men exhibited higher emotional and behavioral distress in response to cognitive intrusions15. A two-factor structure was confirmed by the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), implying distinct dimensions related to the behavioral and emotional reactions to intrusive thoughts15. Considering that thought suppression is an intentional process, being aware and able to understand one’s cognitive processes is essential, which defines the concept of metacognition16. Furthermore, evidence suggests that metacognition is a strong contributor to intrusive thoughts17. As for gender differences, one study reported no significant variation in thought suppression nor intrusive thoughts between men and women18.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the psychometric qualities and validate the Arabic version of the 7-item EBRIQ among adults who speak the Arabic language. Given the usefulness of the scale in groups experiencing psychopathology and those who do not, it is salient to validate the EBRIQ in Arabic, considering the diversity of Arabic-speaking populations. The social and political circumstances are drastically different when contrasting Arabic-speaking countries: for example, the Lebanese population has historically experienced recurrent traumatic events19, while the Emirati population reported significantly higher self-reported happiness in comparison with other Arab countries20. For that reason, the functionality of translating the EBRIQ to Arabic can help explore reactions to intrusive thoughts in distinct Arabic-speaking geographical locations.

Methods

Procedures

The current study is cross-sectional. The data for this investigation was gathered through a Google Forms survey. The data collection stage spanned between November and December 2023, in Lebanon, UAE, Egypt, Jordan and Kuwait. Arabic-speaking adults were asked to complete the survey and send it to other people that would consent to participate. Participants who were considered eligible had to reside in one of the countries mentioned above and be aged above 18 years. Meanwhile, those who could not speak, read and write in Arabic and were under the age of 18 were excluded. The introductory paragraph included the aims of the study and the consent statement to participate in the study. After obtaining informed consent, participants filled the survey. No remuneration was offered in exchange.

Translation procedure

The EBRIQ underwent a translation and adaptation process to tailor it for the Arabic language. The translation process followed international standards21. A forward and backward translation method was conducted, first by a Lebanese translator without study ties and then by a proficient Lebanese psychologist translating back into English. The translations were carefully balanced for specificity22,23,24. An expert committee of two psychiatrists, one psychologist, the researchers, and two translators, compared the original and translated versions, addressing any inconsistencies25. We performed an adaptation of the measure to suit our particular context, aiming to identify any misunderstandings regarding the wording of the items and the ease of interpretation of the items. The adaptation aimed to identify and rectify misunderstandings in wording and interpretation, ensuring conceptual equivalence26. A pilot study with 30 participants confirmed the clarity of the questions, and no changes were made thereafter.

Measures

Emotional and Behavioral Reactions to Intrusions Questionnaire (EBRIQ)15is a seven-question scale that evaluates the variances in reactions to intrusive thoughts both in clinical and nonclinical populations relating to emotional and behavioral states. The items are rated from 1, indicating “Never” or “Very rarely true”, to 5, “Very often” or “Always true”. The EBRIQ includes two factors: emotional reaction to intrusive thoughts and behavioral reaction to intrusive thoughts. Higher scores indicate higher emotions and reactions to intrusive thoughts. The EBRIQ exhibited good reliability and good construct validity15.

The Metacognitions Questionnaire (MCQ-30)was utilized in our study, employing the Arabic version of this 30-item assessment tool, which showed good reliability and validity27. This questionnaire assesses five dimensions of metacognitive beliefs: “Positive beliefs regarding worry,” “Negative beliefs about the uncontrollability and danger of worry,” “Cognitive confidence,” “Cognitive self-consciousness” and “Need to control thoughts.” Each dimension has six statements that are scored from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). Elevated scores show increased maladaptive metacognitive beliefs28 (Cronbach’s α in this study = 0.94).

Analytic strategy

Data treatment

The dataset had no missing responses. SPSS AMOS v.29 software was used to evaluate the factor structure of the EBRIQ. In order to do that, a CFA was conducted. A minimum sample varying between 21 and 140 participants was deemed necessary to conduct a CFA following a recommendation between 3 and 20 times the number of the scale’s variables29. We meant to examine the original model of the EBRIQ. We used the maximum likelihood method to obtain parameter estimates. Calculated fit indices were the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI). Values ≤ 0.08 for RMSEA, and 0.95 for CFI and TLI indicate good fit of the model to the data30. A non-parametric bootstrapping procedure was done, as multivariate normality was not verified in the beginning (Bollen-Stine p = .002).

Sex invariance

A multi-group CFA was used to examine the sex invariance of EBRIQ scores31. Measurement invariance was assessed at the configural, metric and scalar levels32. Evidence of invariance was confirmed by ΔCFI ≤ 0.010 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≤ 0.01031. To compare between males and females, the student t-test was employed only if it was scalar or partial scalar invariance.

Further analyses

The McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha were used to assess composite reliability. Values higher than 0.70 indicated composite reliability that is adequate. Skewness and kurtosis confirmed the normality of the EBRIQ (values for each items ranged between − 1.96 and + 1.96)33. Pearson test was used to correlate EBRIQ scores with MCQ subscales scores using the total sample to test concurrent validity. Values ≤ 0.10 were considered weak, ~ 0.30 were considered moderate, and ~ 0.50 were considered strong correlations34.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 755 adults participated, with a mean age of 21.89 ± 4.18 years and 77.5% females. Table 1 reflects the participants’ characteristics by country. A significantly higher mean age was found in Kuwait, whereas a higher percentage of participants with a medical background was found in Kuwait as well compared to all other countries.

CFA of the EBRIQ

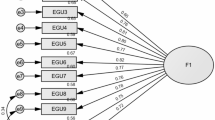

CFA indicated that fit of the one-factor model of EBRIQ scores was modest: RMSEA = 0.251 (90% CI 0.235, 0.267), SRMR = 0.057, CFI = 0.896, TLI = 0.845. When adding correlations between items 5–6, 6–7 and 5–7, the results improved as follows: RMSEA = 0.066 (90% CI 0.047, 0.086), SRMR = 0.014, CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.989. The standardized estimates of factor loadings were all adequate (Fig. 1). Internal reliability was excellent (ω = 0.96; α = 0.96). The AVE value was excellent = 0.75.

Sex invariance

Invariance across sex was proven on the configural, metric, and scalar levels; this was reflected by indices (Table 2). EBRIQ scores between males (M = 10.37, SD = 7.80) and females (M = 10.52, SD = 7.99) showed no difference in the total sample, t(753) = − 0.22, p = .830.

The highest EBRIQ scores were found in Jordanian participants (12.55 ± 6.94), followed by Emirati (12.23 ± 8.20), Lebanese (11.12 ± 7.69), Egyptian (8.96 ± 8.05) and Kuwaiti (8.20 ± 7.75) participants, F(4, 750) = 10.36, p < .001. A significant variance was found between Lebanon and Kuwait (p = .006), UAE and Kuwait (p < .001), Kuwait and Jordan (p < .001), Egypt and Jordan (p = .005), and UAE and Egypt (p = .008) through the post-hoc Bonferroni analysis.

Concurrent validity

Higher cognitive confidence (r = .39; p < .001), positive beliefs (r = .33; p < .001), cognitive self-consciousness (r = .22; p < .001), negative beliefs (r = .57; p < .001) and need to control thoughts (r = .48; p < .001) were significantly associated with higher EBRIQ scores.

Discussion

In this study the EBRIQ scale in Arabic was validated through samples from Lebanon, UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Egypt. The results supported a one-factor structure and the scale exhibited excellent internal reliability (α = 0.96) in comparison with the original scale, which showed a better fit for a two-factor structure and good reliability (r= .68)15. The difference in factor structure can be explained by cultural differences: the first scale was developed in the University of Sheffield, England, an English-speaking sample15 while the current scale was translated for 5 Arabic-speaking countries: Lebanon, UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Egypt.

Also, EBRIQ scores between males and females showed no significant differences. Meanwhile in the original scale15, men showed higher EBRIQ scores. In contrast with the WBSI, women scored higher in thought suppression35,36. These conflicts might be attributed to cultural differences in how men and women feel and act about intrusive thoughts37given that the content of intrusive thoughts depends on social norms and personal values, which are influenced by cultural factors38.

The highest EBRIQ scores were found in Jordanian participants, followed by Emirati, Lebanese, Egyptian and Kuwaiti participants. As previously mentioned, the Arabic-speaking populations are very diverse ethnically and culturally39, with some countries being advanced and others being developing40. Therefore, it is natural that EBRIQ scores are different among Arab countries despite speaking the same language. We can hypothesize that some populations might report higher EBRIQ scores compared to others due to cultural stigmas associated with mental health, subsequently influencing how individuals acknowledge and seek help for intrusive thoughts. For example, stigma and lack of availability of mental health resources were identified as major hurdles for psychological care in Jordan41. In the UAE, residents showing stronger traditional values had a higher probability of having a negative attitude towards mental health issues42. As for Lebanon, research shows that stigma still exists to a lower extent but no explicit discrimination is expressed43. Meanwhile, seeking mental health aid mostly depended on socioeconomic status and availability of financial resources in Egypt44. In Kuwait, a multitude of factors impacted the people’s perception of psychological care including stigma, religious beliefs and the traits of the mental health professional45.

Higher cognitive confidence (r = .39; p < .001), positive beliefs (r = .33; p < .001), cognitive self-consciousness (r = .22; p < .001), negative beliefs (r = .57; p < .001) and need to control thoughts (r = .48; p< .001) were significantly associated with higher EBRIQ scores. Cognitive confidence can contribute to intrusive thoughts, subsequently making symptoms more severe in OCD patients, a population prone to unwanted ideas46. Similarly, cognitive self-consciousness, which is being alert and focused on one’s cognitions, was associated with more intrusive thoughts in nonclinical individuals but also predicted later OCD symptomatology47. In another research, belief that intrusive thoughts are meaningful reinforced the reoccurrence of intrusive ideas later on48. On the other hand, individuals who experienced negative cognitions were more likely to perceive their intrusive thoughts negatively49. In a past study, unsuccessful thought suppression, characterized by reoccurrence of intrusive thoughts, was associated with rumination and neuroticism50. Evidently, failure to control thoughts is related to unsuccessful thought suppression51. In addition, future intrusive thoughts predicted the need to control thoughts52. All of these cognitive factors might increase the probability of engaging in emotional and behavioral reactions to intrusive thoughts in the Arabic-speaking samples presented in the study.

Strengths and limitations

The current study addresses a linguistic gap by translating and validating the EBRIQ for different Arabic-speaking populations. In addition, the sizeable sample employed in the study strengthens the generalizability of the results. It is also important to mention the EBRIQ’s excellent internal reliability demonstrated in the study’s sample (ω = 0.96; α = 0.96). To the best of our knowledge, there are no other validation studies that exist of the EBRIQ, or access is not available. As a result, comparison of the current findings with previous studies is limited. The sample consists of females predominantly, making the current study results less inclusive. Another sample limitation is that the majority of individuals from all participating countries come from a medical background, except from Egypt, which could limit the ability to accurately contrast the results between the samples. Also, the translation of the EBRIQ might require further cross-language validation among other Arabic-speaking populations to ensure language invariance. Lastly, test-retest reliability was not evaluated, which can deter the acknowledgment of the temporal stability of the validated EBRIQ scores.

Future directions

Following the validation of the EBRIQ in Lebanon, UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Egypt, future studies should aim to validate the tool among other diverse Arabic-speaking populations. Future studies should assess the practicality and usefulness of the EBRIQ within clinical samples of different age groups diagnosed with psychopathology that includes intrusive thoughts. The EBRIQ could also be used to evaluate the efficacy of interventions and management techniques aimed at reducing intrusive thoughts.

Conclusion

The EBRIQ scale in the Arabic version was validated for Lebanon, UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Egypt. The results showed no variances between men and women in regards to EBRIQ scores. Higher cognitive confidence, positive beliefs, cognitive self-consciousness, negative beliefs and need to control thoughts were significantly associated with higher EBRIQ scores. Therefore, this study suggests that our Arabic translation of the EBRIQ is psychometrically proven to be reliable for use in Lebanon, UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Egypt, where this validated tool can allow researchers and practitioners to assess emotions and behaviors related to intrusive thoughts.

Data availability

Because of ethical committee constraints, none of the data collected or analyzed during this study are publicly available. However, the corresponding author (SH) may make the data available upon reasonable request.

Change history

23 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99081-x

References

Clark, D. A. Intrusive Thoughts in Clinical Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 1 edn (Guilford, 2004).

Berry, L-M. & Laskey, B. A review of obsessive intrusive thoughts in the general population. J. obsessive-compulsive Relat. Disorders. 1 (2), 125–132 (2012).

Arnáez, S., García-Soriano, G., López‐Santiago, J. & Belloch, A. Illness‐related intrusive thoughts and illness anxiety disorder. Psychol. Psychother. 94 (1), 63–80 (2021).

Bomyea, J. & Lang, A. J. Accounting for intrusive thoughts in PTSD: contributions of cognitive control and deliberate regulation strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 192, 184–190 (2016).

Gay, P., Schmidt, R. E. & Van der Linden, M. Impulsivity and intrusive thoughts: related manifestations of self-control difficulties? Cogn. Therapy Res. 35 (4), 293–303 (2011).

Batey, H., May, J. & Andrade, J. Negative intrusive thoughts and dissociation as risk factors for self-harm. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 40 (1), 35–49 (2010).

Donaghey, C., Egan, J. & O’Súilleabháin, P. S. J. C. P. T. Psychological factors of intrusive thoughts in an Irish student population. Clin. Psychol. Today. 1(1), 24–41 (2018).

Hassan, W. et al. Variations in obsessive compulsive disorder symptomatology across cultural dimensions. Front. Psychiatry. 15, 1329748 (2024).

Momani, M. A. A., Abdalrahim, M. S., Shoqirat, N., Zeilani, R. S. & Dardas, L. A. In the shadows of OCD: Jordanian patients’ experiences during the COVID-19 quarantine. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 32(1), (2024).

Algadeeb, J., Alramdan, M. J., AlGadeeb, R. B. & Almusawi, K. N. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Gulf countries: a narrative review. Cureus 16 (8), e67381 (2024).

Abd-Elhamed, M. E. M., Ghaith, R. F. A. H., Mohamed, B. E. S. & Mohammed, S. F. M. Alexithymia and suicidal ideation among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Zagazig Nurs. J. 20 (2), 346–358 (2024).

Moss, A. C., Erskine, J. A. K., Albery, I. P., Allen, J. R. & Georgiou, G. J. To suppress, or not to suppress? That is repression: Controlling intrusive thoughts in addictive behaviour. Addict. Behav. 44, 65–70 (2015).

Wegner, D. M. & Zanakos, S. Chronic thought suppression. J. Pers. 62 (4), 615–640 (1994).

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H. & Horselenberg, R. Individual differences in thought suppression. The White Bear suppression inventory: factor structure, reliability, validity and correlates. Behav. Res. Ther. 34 (5), 501–513 (1996).

Berry, L-M., May, J., Andrade, J. & Kavanagh, D. Emotional and behavioral reaction to intrusive thoughts. Assess. (Odessa Fla). 17 (1), 126–137 (2010).

Takarangi, M. K. T., Nayda, D., Strange, D. & Nixon, R. D. V. Do meta-cognitive beliefs affect meta-awareness of intrusive thoughts about trauma? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 54, 292–300 (2017).

Myers, S. G. & Wells, A. An experimental manipulation of metacognition: a test of the metacognitive model of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 51 (4–5), 177–184 (2013).

Barnes, R. D., Klein-Sosa, J. L., Renk, K. & Tantleff-Dunn, S. RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THOUGHT SUPPRESSION, INTRUSIVE THOUGHTS, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS. J. Cogn. Behav. Psychotherapies. 10 (2), 131 (2010).

Beydoun, H. & Mehling, W. Traumatic experiences in Lebanon: PTSD, associated identity and interoception. Eur. J. Trauma. Dissociation. 7, 4 (2023).

D’Raven, L. L. & Pasha–Zaidi, N. Happiness in the United Arab Emirates: conceptualisations of happiness among Emirati and other arab students. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2 (1), 1–21 (2015).

van Widenfelt, B. M., Treffers, P. D. A., de Beurs, E., Siebelink, B. M. & Koudijs, E. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of Assessment instruments used in Psychological Research with children and families. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 8 (2), 135–147 (2005).

Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Psychometric properties of the arabic version of the intuitive eating Scale-2 (IES-2) in a sample of community adults. J. Eat. Disorders. 11 (1), 53–53 (2023).

Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Psychometric properties of the arabic versions of the three-item short form of the modified Weight Bias internalization scale (WBIS-3) and the Muscularity Bias internalization scale (MBIS). J. Eat. Disorders. 11 (1), 82–82 (2023).

Azzi, N. M. et al. Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the short form of Weinstein noise sensitivity scale (NSS-SF) in a community sample of adolescents. BMC Psychol. 11 (1), 1–384 (2023).

Fenn, J., Tan, C-S. & George, S. Development, validation and translation of psychological tests. BJPsych Adv. 26 (5), 306–315 (2020).

Ambuehl, B. & Inauen, J. Contextualized measurement scale adaptation: a 4-Step tutorial for health psychology research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (19), 12775 (2022).

Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the short form of the metacognition questionnaire (MCQ-30) in a non-clinical adult sample. BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1), 1–795 (2023).

Wells, A. & Cartwright-Hatton, S. A short form of the metacognitions questionnaire: properties of the MCQ-30. Behav. Res. Ther. 42 (4), 385–396 (2004).

Mundfrom, D. J., Shaw, D. G. & Ke, T. L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test. 5 (2), 159–168 (2005).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6 (1), 1–55 (1999).

Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14 (3), 464–504 (2007).

Vandenberg, R. J. & Lance, C. E. A review and synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for Organizational Research. Organizational Res. Methods. 3 (1), 4–70 (2000).

Hair, J. F. Jr et al. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 1st 2021;1st 2021; edn (Springer International Pub, 2021).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 (1), 155–159 (1992).

Cichoń, E., Szczepanowski, R. & Niemiec, T. Polish version of the White Bear suppression inventory (WBSI) by Wegner and Zanakos: factor analysis and reliability. Psychiatr. Pol. 54 (1), 125 (2020).

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N. & Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish Version of the White Bear suppression inventory. Psychol. Rep. 94 (3), 782–784 (2004).

Clark, D. A. & İnözü, M. Unwanted intrusive thoughts: cultural, contextual, covariational, and characterological determinants of diversity. J. Obsessive-Compulsive Relat. Disorders. 3 (2), 195–204 (2014).

Radomsky, A. S. et al. Part 1—You can run but you can’t hide: intrusive thoughts on six continents. J. obsessive-compulsive Relat. Disorders. 3 (3), 269–279 (2014).

Kilian-Yasin, K. & Al Ariss, A. J. G. L. P. A. C. C. M. P. Understanding the culture of Arab countries: diversity and commonalities. 253. (2014).

Kamal, R. & Moukaddem, S. The Arab world: Advance amid diversity. In: The New Third World 184–200 (Routledge, 2019).

Al-Qerem, W. et al. Assessing mental health literacy in Jordan: a factor analysis and Rasch analysis study. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1396255 (2024).

Andrade, G. et al. Attitudes towards mental health problems in a sample of United Arab Emirates’ residents. Middle East. Curr. Psychiatry. 29 (1), 88 (2022).

Abi Hana, R. et al. Mental health stigma at primary health care centres in Lebanon: qualitative study. Int. J. Mental Health Syst. 16 (1), 23 (2022).

Ibrahim, N., Ghallab, E., Ng, F., Eweida, R. & Slade, M. Perspectives on mental health recovery from Egyptian mental health professionals: a qualitative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 29 (3), 484–492 (2022).

Scull, N. C., Khullar, N., Al-Awadhi, N. & Erheim, R. A qualitative study of the perceptions of mental health care in Kuwait. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 3 (4), 284–299 (2014).

Nedeljkovic, M., Moulding, R., Kyrios, M. & Doron, G. The relationship of cognitive confidence to OCD symptoms. J. Anxiety Disord. 23 (4), 463–468 (2009).

Cohen, R. J. & Calamari, J. E. Thought-focused attention and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: an evaluation of cognitive self-consciousness in a nonclinical samples. Cogn. Therapy Res. 28 (4), 457–471 (2004).

Teachman, B. A., Woody, S. R. & Magee, J. C. Implicit and explicit appraisals of the importance of intrusive thoughts. Behav. Res. Ther. 44 (6), 785–805 (2006).

Wilksch, S. R. & Nixon, R. D. V. Role of prior negative cognitions on the development of intrusive thoughts. Australian J. Psychol. 62 (3), 121–129 (2010).

Ryckman, N. A. & Lambert, A. J. Unsuccessful suppression is associated with increased neuroticism, intrusive thoughts, and rumination. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 73, 88–91 (2015).

Clark, D. A. & Purdon, C. Mental Control of unwanted intrusive thoughts: a phenomenological study of nonclinical individuals. Int. J. Cogn. Therapy. 2 (3), 267–281 (2009).

Wahl, K., Hofer, P. D., Meyer, A. H. & Lieb, R. Prior beliefs about the importance and control of thoughts are predictive but not specific to subsequent intrusive unwanted thoughts and neutralizing behaviors. Cogn. Therapy Res. 44 (2), 360–375 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FFR, SO, SH, DM designed the study; EA drafted the manuscript; SH carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; AA, MH, MR, SAR, RA, NF, REH, and JM collected the data. DM, RH, MB and SEK reviewed the paper for intellectual content; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and gave their consent.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human Ethics and Consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board in the Faculty of Pharmacy at Applied Science Private University (Jordan) with an approval number of 2023-PHA-43. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects; the online submission of the soft copy was considered equivalent to receiving a written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this article, the author name ‘Rita El Hajjar’ was duplicated and given as ‘Rita El Hagar’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awad, E., Malaeb, D., Alhuwailah, A. et al. Psychometric properties of the Arabic emotional and behavioral reaction to intrusions questionnaire among sample of Arabic speaking adults. Sci Rep 15, 4728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86786-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86786-2