Abstract

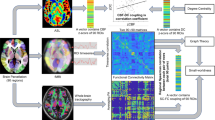

To investigate the presence of modular loss of coupling and abnormal alterations in functional and structural networks in the brain networks of patients with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). We collected resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data and diffusion tensor imaging data from 82 healthy controls (HCs) and 71 PHN patients, generated structural connectivity (SC) and functional connectivity (FC) networks, and assessed the corresponding clinical information assessment. Based on AAL(90) mapping, the brain network was divided into 9 modules, and the structural–functional connectivity (SC–FC) coupling was compared at the whole-brain level and within the modules, as well as alterations in the topological properties of the brain network in the patient group. Finally, correlation analyses were performed using the following clinical scales: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD). Compared with HCs, patients with PHN had reduced global efficiency (Eg) and local efficiency (Eloc) of structural and functional networks. The FC in the PHN group presented abnormal node clustering coefficients (NCp), local node efficiencies (NLe), and node efficiencies (Ne), and the SC presented abnormal node degrees (Dc), NCp, NLe, characteristic path lengths (NLp), and Ne. In addition, SC–FC coupling was reduced in the patient default network (DMN), salient network (SN), and visual network (VIS). Moreover, the degree of impairment of graph theory indicators was significantly positively correlated with scales such as VAS scores, and the coupling of modules was significantly negatively correlated with the early course of the patient’s disease. Large-scale impaired topological properties of the FC and SC networks were observed in patients with PHN, and SC–FC decoupling was detected in these modules of the DMN, SN, and VIS. These aberrant alterations may have led to over-transmission of pain information or central sensitization of pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can induce herpes zoster (HZ) and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN)1. VZV establishes a lifelong latent infection in the neurons of 90% of the population, and in one-third of the population, reactivation of VZV leads to HZ due to a compromised immune system; this usually presents as a characteristic unilateral rash along 1 or 2 dermatomes, which usually disappears within a few weeks2. Postherpetic neuralgia is one of the most serious complications of HZ and refers to persistent pain for more than 1 month after herpes zoster infection is cured3. Clinically, it usually manifests as localized pain of different types in the skin, which can be accompanied by sleep disorders and emotional changes, and in severe cases, it can cause depression and suicidal thoughts in patients4. Currently, the clinical diagnosis of PHN is well defined, However, there are no effective treatments for PHN, and its neuropathological mechanisms remain unclear5.

In recent years, through intensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we have shown that disease states lead to the presence of abnormal alterations in structural connectivity (SC) and functional connectivity (FC) in brain networks6,7,8. Currently, a study has applied graph theoretic analysis to calculate the topological properties of FCs for patients with PHN, and the results show that patients with PHN exhibit reduced FCs in several brain regions, including the pain substrate and precuneus and cingulate gyrus9, indicating that there are widely reduced global and nodal efficiencies, as well as increased characteristic path lengths, in the functional networks of PHN patients10,11. The above results suggest disruption of the modular organization of functional brain networks, altered functional small-world properties, and impaired functional connectivity in patients with PHN9,12; however, past studies have not much explored the effects of PHN on the topological organization of brain structural networks. Notably, patients with PHN exhibit extensive alterations in the diffusion properties of fiber bundles13. Few studies have analyzed DTI data from PHN patients with SC, and FC and SC are combined in that they can more sensitively detect changes in brain microstructure organization and better interpret abnormal alterations in brain connectivity14. Various studies have shown that both SC and FC complement each other; SC implies physiological anatomical limitations, whereas FC influences SC through brain plasticity15,16,17; i.e., greater coupling suggests that anatomical structures have limitations in functional transmission. Similarly, we can apply this approach to probe the neuropathological mechanisms of PHN in depth at the network level.

The human brain is a complex network that can operate efficiently due to its ability to simultaneously separate and integrate functionally through specific connectivity patterns, thus ensuring information transmission efficiency and information integration18. Therefore, it is not comprehensive enough for us to focus only on structural–functional connectivity (SC–FC) coupling at the whole-brain level, and the analysis of SC–FC coupling can link structural networks and functional networks for integrated consideration, which can reveal the mechanism of the disease in a more comprehensive and deeper way than studies using one imaging method alone14. The modular structure of the human brain network contains many relevantly connected nodes, which are usually the basic units for processing information. In addition, modularity is an important feature of brain networks; i.e., brain regions are tightly connected within groups and sparsely connected between groups19,20,21. Functionally coupled modules contribute to a balance between functional separation and integration, ensuring efficient intra-module information processing along with fast inter-module information exchange and high resilience to network nodes and impaired connectivity22,23,24. Human brain networks have a well-defined modular organization, and this study classified human brain networks into nine sub-networks based on past literature: visual, auditory, default, salience, sensorimotor, frontoparietal, cingulate insula-covered, attentional, and subcortical networks25. Chronic pain and physical or psychological stressors may lead to progressive functional and structural changes in brain networks and maintain or enhance cognitions/emotions about the pain experience26; however, it remains unclear whether the altered organization of structural and functional connectivity is selectively disrupted in chronic pain patients. We will analyze whether there are selective SC–FC coupling alterations in the above nine modules at the module level.

The aims of our analyses were as follows: (i) to explore the altered nature of structural versus functional network graph theory in patients with PHN, (ii) to explore whether SC–FC coupling is altered in patients at the whole-brain level, (iii) to further explore whether the modular organization of the 9 major sub-networks exhibits abnormal SC–FC coupling, and (iv) to further analyze the relationship between the relevant alterations and the clinical information, assuming that the above studies revealed abnormal alterations in the brain networks of the patients. Our hypothesized SC–FC coupling was altered at the multi-scale network level (i.e., at the whole-brain and modular levels). The above studies could further improve the knowledge of the central neuropathological mechanisms of PHN.

Materials and methods

Subjects and data collection

Patients with PHN in the pain department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from March 2018 to December 2023 were collected for magnetic resonance scanning and subjects were assessed for physical condition and completed clinical scales by an experienced pain physician. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) right-handed, (2) persistent pain for 1 month or longer after the healing of herpes zoster rash, (3) An experienced pain physician will assess the patient’s pain level using the VAS (Visual Analog Pain Score), and patients with a VAS score greater than 4 will be selected, and (4) patients with herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia with herpes zoster occurring mostly in the anterior and posterior chest regions. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) herpes zoster in specific areas (eyes, ears), (2) suffering from other persistent acute or chronic pain, (3) suffering from neurologic or psychiatric disorders, (4) history of head trauma or alcohol or drug abuse, or (5) contraindications to MRI. We initially included 100 PHN and 100 HC subjects and excluded 47 subjects with poor image quality (e.g., significant head movement, motion artifacts, and preprocessing failures and poor spatial alignment of the images); ultimately, 71 PHN and 82 HC subjects were included in this study, the PHN group included 36 males and 35 females; the HC group included 40 males and 42 females. We used Gpower 3.1.9.7 software to demonstrate our sample size.

All the subjects completed the VAS (patient group), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) before the MRI scan.

Image acquisition and preprocessing

Data acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a 3.0T Siemens Trio TIM scanner (Erlangen, Bavaria, Germany) and an 8-channel phased-array head quadrature coil in the Department of Radiology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. The fMRI data were obtained using an echo planar imaging sequence. The scanning parameters were as follows: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view (FOV) = 220 × 220 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, 30 interleaved axial slices, layer thickness = 4.0 mm, and scanning time point = 240. 3D high-resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired with TR = 1900 ms, TE = 2.26 ms, flip angle = 9°, FOV = 215 × 230 mm, matrix = 240 × 256, 176 sagittal slices, and 1-mm layer thickness. During the MRI scan, patients were asked to close their eyes, try not to think, and avoid falling asleep while the MRI scan was performed.

Functional magnetic resonance data preprocessing

All pre-processing of functional data was performed via Statistical Parametric Plotting (SPM12). Statistical parametric mapping (SPM12) and brain imaging data processing and analysis were performed on a MATLAB platform. The first 10 volumes were discarded to stabilize the magnetic field. The usual step slice timing was omitted because we used a short TR (800 ms) to avoid diffusion effects. Slice timing was omitted. Head motion correction motion was performed on the remaining images and realigned with the first image. To minimize unwanted motion-related effects, subjects with head movement motion above a 2.5 mm threshold were excluded. Regressions were then performed on the interfering covariates, including Friston-24 partial motion parameters and white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals. Afterward, the functional images were spatially normalized to standard stereotaxic space (Montreal Neurological Institute [MNI] template) for spatial normalization. Anatomical alignment by power series algebra was performed according to the corresponding co-registration and spatial segmentation of the T1-weighted images. In addition, 4-mm isotropic Gaussian kernel smoothing and bandpass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) were used.

DTI data preprocessing

All DTI data were preprocessed using FMRIB’s diffusion tensor imager and FMRIB’s software library. The specific steps for DTI data preprocessing were as follows: (1) convert DICOM images to the NIFTI format, (2) perform b0 image extraction, (3) perform brain extraction, (4) correct for vorticity and head motion, and (5) compute fractional anisotropy (FA) using linear least squares fitting method.

Network construction

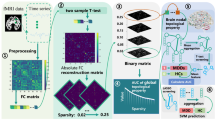

To construct the functional and structural networks, an automated anatomical atlas, AAL90, was used as a profile of the entire brain, through which each node was defined as one of 90 regions of interest. Functional and structural networks are constructed of uniformly weighted types.

Construction of the FC network

Regional blood oxygen level-dependent signal time series of rs-fMRI data were extracted by averaging voxel time series data. The FC value between any two nodes was calculated based on the Pearson correlation between the regional time series. A weighted functional network with a 90 × 90 FC matrix was constructed for each subject.

Construction of the SC network

Based on the “Pipeline for Analyzing Brain Diffusion Images” software on Linux and MATLAB for brain network construction, the specific steps for defining the nodes and edges of the network were as follows. (1) Definition of network nodes: Briefly, 3D T1-weighted images of each subject were aligned with b 0 images in DTI space (nondiffusion-weighted gradient direction), and then the transformed T1 images were further nonlinearly aligned to the MNI-ICBM 152 template. The auto-anatomical labeling template was then warped from MNI space to DTI space using an inverse transformation. In this way, a structured brain network with 90 nodes (45 per cerebral hemisphere) was obtained. (2) Network edge definition: Fiber tracking and whole-brain fiber construction were performed by fiber assignment based on the continuous tracking (FACT) algorithm. Fiber bundle tracking stopped when the fractional anisotropy (FA) was less than 0.2 or the tracking steering angle between two connections was greater than 45°. We chose a threshold for fiber bundles to reduce the effect of misconnections. Two regions were considered to be structurally connected (network edges) if at least three fibers were present (T = 3). We defined the weight of the edge (wij) as the product of the number of fiber bundles (FNs) in the white matter fiber tracts between any two brain regions and the average FA value of the fiber tracts (wij = FNij × FAij). A weighted brain structural network (90 × 90) with the composite properties of the fiber bundles can thus be constructed for each subject.

Application of graph theoretic analysis

The Graphical Theoretical Network Analysis Toolkit (GRETNA) was used to measure functional and structural network properties through theoretical graphical analysis. Global (network efficiency and small-world properties) and node topology metrics were calculated for each participant. The global network efficiency metrics include global efficiency (Eglob) and local efficiency (Eloc). For small-world characteristics, five evaluation metrics were used: the clustering coefficient (Cp), characteristic path length (Lp), normalized clustering coefficient (γ = Creal/Cmean random), normalized characteristic path length (λ = Lreal/Lmean random) and small-world characteristics (σ = γ/λ). The node-to-topology metrics include betweenness centrality (BC), degree centrality (DC), node efficiency (NE), node local efficiency (NLE), and the node clustering coefficient (NCP). The functional network analysis employed a series of sparsity thresholds (ranging from 0.04 to 0.4 with an interval of 0.01) to ensure that the generated networks could be used for small-world estimation with sparse properties while minimizing the number of spurious edges.

Coupling of the FC and SC networks

First, we generated the FA * FN network via dot-production of the FA matrix with the FN matrix on the basis of previous studies, considering both dimensions of the microstructure. We subsequently calculated the coupling values between the SC network (FA * FN network) and the FC network separately. SC–FC coupling analysis, which refers to the correlation analysis between the strength of structural connections and functional connections, has been described in previous studies. In this study, we not only performed SC–FC coupling analysis at the whole-brain level but also explored the relationship between FC and SC matrices and networks at the modular level. Modularity is a feature of complex networks that reflects the subspecialization of the network into smaller modules. Each module contains several densely interconnected nodes, whereas connections between nodes in different modules are relatively sparse27. The modular SC–FC coupling was computed by the Spearman rank correlation between a row of the SC matrix and the corresponding row of the FC matrix (excluding self-connections). For the nine modules, which include the visual, auditory, default-mode, salience, sensorimotor, frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular, attention and subcortical subnetworks, the intra-module SC–FC coupling was computed as the Spearman correlation of the structural and functional connections between the module and the other modules.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 23.0). Sex differences were compared using the χ2 test, continuous variables were tested for conformity to a normal distribution, conformity to a normal distribution was tested using the independent samples t test, and non-conformity was tested using non-parametric tests and post hoc Bonferroni correction. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Correlation analyses were used to explore the relationships between clinical assessments (total VAS, HAMD, and HAMA scores) and network attributes after controlling for sex, age, and education level (p < 0.05).

The broad research process is shown in Fig. 1.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1

See Table 1.

Nature of functional and structural network graph theory in PHN patients

In all subject groups, we observed small-world properties. Compared with those of the HCs, the Sigma and Gamma values of the SC network in the PHN group were greater; the Sigma and Gamma values of the FC network were lower, but the difference was not statistically significant. The FC and SC networks in the PHN group presented a decrease in global efficiency (Eg) and local efficiency (Eloc), as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. In addition, the patients in the PHN group showed a significant decrease in the two networks and showed significant decreases in DC, Ne, NCp, and NLe in some nodes, as well as elevated NLp, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. After testing the obtained difference nodes we performed a multiple test using the Bonferroni correction and the results were still significantly different. For details, see Table 2.

SC–FC coupling results in PHN patients at the whole-brain level

There was no significant difference in SC–FC coupling between the PHN and HC groups at the level of the whole-brain network (p = 0.21 > 0.05), as shown in Fig. 6.

SC–FC coupling results for PHN patients at the module level

Among the nine modules, the PHN patients presented significantly lower coupling within the default mode network, salience network, and visual network modules than the HCs, as shown in Fig. 7. After testing the obtained difference modules we performed a multiple test using the Bonferroni correction and the results were still significantly different. The differences in coupling within each module are detailed in Table 3.

Clinical relevance

We correlated the difference graph theory metrics as well as the three different subnetwork coupling values with the clinical scales, as shown in Fig. 8.

We found a significant negative correlation between disease duration and SC–FC coupling of default and salient network modules in patients with early PHN (30–90 days), as shown in Fig. 9.

Discussion

This is the first time that DTI and rs-fMRI methods have been combined to explore the central neuropathological mechanisms of PHN from the perspective of structure–function coupling. The main findings of this study are as follows: (1) Compared with those of HCs, the brain network graph theory topology metrics of the PHN group exhibited significant and extensive attenuation, as evidenced by the global efficiency, node efficiency, local node efficiency, degree centrality, and clustering coefficient. (2) Compared with HCs, some subnetwork couplings in the PHN group exhibited attenuated alterations. (3) The module-level SC–FC coupling values of PHN patients were significantly negatively correlated with their disease duration (within 90 days), and some graph-theoretic topology metrics were significantly correlated with clinical metrics, such as the VAS, HAMA, and HADA.

In the present study, our topological results revealed that patients in the PHN group had lower Eg and Eloc values, as well as longer characteristic paths Lp, suggesting that the overall and local nodes of the human brain network have reduced transmission capacity and slower transmission of information in the network28. The elevated Sigma of SC networks in PHN patients indicates a greater degree of local specialization and overall integration of structural networks. However, Gamma is usually interpreted as an indicator of the strength of network segregation or specialization29. The diametrically opposite changes in these two metrics, the FC network and SC network, may be related to structural compensatory mechanisms. DC values can be a good response to the connectivity of a certain brain region or node in the whole-brain network hub, and its response to the degree of node centrality is more reliable for specifically evaluating the alteration of the brain network30. The Cp is usually used to assess the information processing efficiency of brain networks, whereas the Ne, NLe, and NCp are related to the efficiency of local node information transfer27. All of the above metrics are reduced in response to the impaired structural and functional networks in PHN patients. These abnormal nodes with reduced topological properties were mostly distributed in the default, salient, and visual networks. Moreover, we found that the SC–FC coupling of these subnetworks was abnormally altered. Our study suggested that the DMN, SN, and VIS modules are more detached from anatomical channels in PHN patients.

SC–FC coupling represents a pairwise relationship between structural and functional networks and has been widely used to explore changes in the progression of neurological diseases31,32,33. We failed to analyze SC–FC coupling at the whole-brain level to show that there was a between-group difference between the PHN and HC groups, suggesting that intact SC–FC associations are still present in the brain integration of PHN patients. Whereas abnormal alterations in SC–FC coupling were found at the level of modular networks, we hypothesized that there may be several reasons for this. On the one hand, module-dependent SC–FC coupling must preferentially capture subtle changes in neural activity in the PHN. We found a significant negative correlation between disease duration and SC–FC coupling of default and salient network modules in patients with early PHN (30–90 days), demonstrating that reorganization of brain networks is absent in the early stages of PHN and that the worsening of the disease state with the progression of the disease leads to accelerated changes in the SC–FC coupling of the modules; however, a more detailed mechanism needs to be confirmed by further longitudinal studies. On the other hand, SC–FC coupling represents the asynchronous nature of functional and structural connectivity; i.e., aberrant SC–FC coupling may result from inconsistent changes in structural and functional networks34. In the early lesioned brain, to maintain the diversity of functional organization and the interplay of neural activity, structural deficits may lead to the diversification of large-scale coherent functional network patterns and highly dynamic properties, resulting in the disruption of SC–FC coupling35,36,37. Therefore, we believe that the results of the modular level study may be superior to those of the whole-brain level, and previous studies have noted that regional SC–FC coupling is a specific feature of brain organization, and that the strength of its coupling varies greatly between brain regions and is influenced by genetic factors38, which also illustrates the need for analysis at the module level.

The default network (DMN) plays an important role in maintaining the efficiency of pain inhibition in healthy states and painful conditions, and disturbances in DMN dynamics are associated with chronic pain states39,40. A previous study revealed that DMN disorder from the acute herpes zoster period was a long-term phenomenon that persisted after the characteristic pain disappeared. This is consistent with our finding that abnormal alterations in SC–FC coupling of DMN subnetworks occurred in line with the above results and that the posterior cingulate gyrus, as a core hub of the DMN, showed a significant negative correlation between its DC and Ne values and VAS scores. Additionally, its NLp showed a significant positive correlation with VAS scores, which, from an information flow perspective, implies that pain generation and pain sensitization may be closely related to the disturbance of information exchange in this node. The above results may provide some clues for further research on the neural mechanisms of PHN. Our study also revealed that the SC–FC coupling of the synaptic network module was reduced, suggesting that the coherence of the functional and structural connectivity network within this module was altered. The synaptic network, with the ACC and insula as core nodes, is thought to be involved in directing attention to salient stimuli, such as pain41, and in patients with intractable tumor pain who have undergone cordotomy or cingulotomy, the connectivity of the prominence network is reduced42. In addition, increased connectivity in parts of the synaptic network (insula and anterior cingulate gyrus) is observed in patients with chronic pain syndromes, low back pain, and migraines43,44,45. These results invariably suggest that the resting-state connectivity of the salience network is a hallmark of chronic pain perception. In the present study, we found that the SC‒FC coupling of the salient network was reduced in patients with PHN, suggesting that the function of patients with PHN is detached from the structure to a certain extent in the painful state. The significant negative correlation between patients’ VAS scores and the coupling values at the level of the DMN and SCN modules in this study also suggested that the degree of coupling within the two subnetworks of the DMN and SCN severely affects patients’ ability to perceive pain. A number of studies have reported that visually related brain regions are involved in pain modulation, but the exact mechanism remains unclear, which may be related to the fact that visual distraction can improve pain tolerance by diverting attention away from pain, thus reducing the intensity of perception46. Vision is an important part of the selective attention process47, and vision is involved in the integration of brain functions in chronic pain through central neural cross-modal integration48. In patients with PHN, scholars have reported alterations in neural activity involving parts of the visual network as well as in gray matter volume49, which is similar to our findings. The reduced SC–FC coupling in the visual network of PHN patients may be a result of long-term adaptation to pain. We understand that the disruption of structure–function relationships in the sensory cortex of PHN patients is due to increased degradation of myelin as well as axons13, which in turn affects the biased perception of pain-related visual stimuli.

Many previous studies have confirmed substantial congruence between SC–FC coupling and the hierarchical, cytoarchitectural, and evolutionary expansion of cortical function and have also shown that flexible functional reconstruction and efficient multifunctional integration rely on fewer anatomical constraints50,51,−52. Therefore, anatomically, too few constraints (i.e., SC–FC uncoupling) may lead to over-transmission of information, which also includes nociception perception. PHN is often thought to result from abnormal hyperexcitability of neurons associated with pain or enhanced synaptic transmission, which amplifies pain signaling53; this idea highly overlaps with our findings.

In conclusion, our study identified changes in specific sub-networks in patients with PHN, and these findings differ from those of previous pain-related studies, reveal that the DMN, SCN, and VIS may play a synergistic role in different stages of pain information processing through multi-level structural connections and functional interactions. The observed structural-functional decoupling of these three networks in PHN patients may reflect the disruption of dynamic balance in brain networks during pain adaptation, leading to the maintenance and amplification of pain. Further investigation into the decoupling mechanisms of these networks is crucial for understanding the neuropathological basis of PHN.

Several limitations should be noted in this study. First, in constructing structural and functional brain networks, we divided the entire brain into 90 regions based on previously published maps. Future studies could select nodes based on different brain anatomical or functional templates. Second, the cross-sectional design of the present study did not allow us to assess the dynamic evolution of structural and functional network changes; therefore, future longitudinal studies are necessary. This experiment only examined the sub-network of PHN patients and the HC group that differed in coupling at the module level, and did not address other chronic pain; in the future, we will compare PHN pain with other types of pain to discover the most characteristic indicators of PHN pain. Finally, the sample size of this group was small; therefore, future studies need to be supported by larger sample sizes.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that patients with PHN show large-scale network topological property impairments in functional and structural networks, as well as abnormal alterations in selective SC–FC coupling at the modular level, compared with HCs. These impairments may be related to symptoms of persistent pain in PHN patients. Our findings provide a neural basis for large-scale brain network alterations in PHN patients and provide valuable information for elucidating the neuropathologic mechanisms of PHN.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Peng, Q. et al. Dynamic immune landscape and VZV-specific T cell responses in patients with herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Front. Immunol. 13, 887892 (2022).

Curran, D. et al. Healthy ageing: Herpes zoster infection and the role of zoster vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 8 (1), 184 (2023).

Giannelos, N. et al. The incidence of herpes zoster complications: A systematic literature review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 13 (7), 1461–1486 (2024).

Fan, H. R. et al. Early diagnosis of herpes zoster neuralgia: A narrative review. Pain Ther. 12 (4), 893–901 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. PROCESS trial: Effect of duloxetine premedication for postherpetic neuralgia within 72 hours of herpes zoster reactivation-a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 78 (4), 880–888 (2024).

Xu, M. et al. Reconfiguration of structural and functional connectivity coupling in patient subgroups with adolescent depression. JAMA Netw. Open 7 (3), e241933 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Effects of computerized cognitive training on structure–function coupling and topology of multiple brain networks in people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15 (1), 158 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Disrupted rich-club network organization and individualized identification of patients with major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 108, 110074 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Decreased functional connectivity of the core pain matrix in herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia patients. Brain Sci. 13 (10), (2023).

Li, J. et al. Greater functional connectivity between the ventral frontal cortex and occipital cortex in herpes zoster patients than post-herpetic neuralgia patients. Br. J. Radiol. 96 (1141), 20220762 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. A study on small-world brain functional networks altered by postherpetic neuralgia. Magn. Reson. Imaging 32 (4), 359–365 (2014).

Jiang, X. et al. Aberrant functional and causal connectivity of the amygdala in herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia patients. Br. J. Radiol. 96 (1152), 20230338 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Altered white matter microstructure in herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia determined by automated fiber quantification. Brain Sci. 12 (12). (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Understanding structural-functional relationships in the human brain: A large-scale network perspective. Neuroscientist 21 (3), 290–305 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Altered functional-structural coupling of large-scale brain networks in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Brain 134 (Pt 10), 2912–2928 (2011).

Koenis, M. M. G. et al. Associations of cannabis use disorder with cognition, brain structure, and brain function in African americans. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42 (6), 1727–1741 (2021).

Feng, G. et al. Spatial and temporal pattern of structure-function coupling of human brain connectome with development. Elife 13 (2024).

Sporns, O. Network attributes for segregation and integration in the human brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23 (2), 162–171 (2013).

Park, H. J. & Friston, K. Structural and functional brain networks: From connections to cognition. Science 342 (6158), 1238411 (2013).

Sporns, O., Tononi, G. & Edelman, G. M. Theoretical neuroanatomy: Relating anatomical and functional connectivity in graphs and cortical connection matrices. Cereb. Cortex 10 (2), 127–141 (2000).

Kötter, R. & Stephan, K. E. Network participation indices: Characterizing component roles for information processing in neural networks. Neural Netw. 16 (9), 1261–1275 (2003).

Latora, V. & Marchiori, M. Efficient behavior of small-world networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87 (19), 198701 (2001).

Han, J. D. et al. Evidence for dynamically organized modularity in the yeast protein-protein interaction network. Nature 430 (6995), 88–93 (2004).

van den Heuvel, M. P. & Sporns, O. Network hubs in the human brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 (12), 683–696 (2013).

Long, Y. et al. Psychological resilience negatively correlates with resting-state brain network flexibility in young healthy adults: A dynamic functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann. Transl. Med. 7 (24), 809 (2019).

Apkarian, V. A., Hashmi, J. A. & Baliki, M. N. Pain and the brain: Specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 152 (3 Suppl), S49–s64 (2011).

Bullmore, E. & Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: Graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10 (3), 186–198 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Shorter TR combined with finer atlas positively modulate topological organization of brain network: A resting state fMRI study. Network 34 (3), 174–189 (2023).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52 (3), 1059–1069 (2010).

Cornelis, I. et al. Clinical presentation, diagnostic findings, prognostic factors, treatment and outcome in dogs with meningoencephalomyelitis of unknown origin: A review. Vet. J. 244, 37–44 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Aberrant dynamic functional-structural connectivity coupling of large-scale brain networks in poststroke motor dysfunction. Neuroimage Clin. 37, 103332 (2023).

Bi, K. et al. Dynamic functional-structural coupling within acute functional state change phases: Evidence from a depression recognition study. J. Affect. Disord. 191, 145–155 (2016).

Martino, M. et al. Abnormal functional-structural cingulum connectivity in mania: Combined functional magnetic resonance imaging-diffusion tensor imaging investigation in different phases of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 134 (4), 339–349 (2016).

Lim, S. et al. Discordant attributes of structural and functional brain connectivity in a two-layer multiplex network. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2885 (2019).

van den Heuvel, M. P. et al. Abnormal rich club organization and functional brain dynamics in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 70 (8), 783–792 (2013).

Li, K. et al. Abnormal rich club organization and impaired correlation between structural and functional connectivity in migraine sufferers. Brain Imaging Behav. 11 (2), 526–540 (2017).

Zhao, S. et al. Sex differences in anatomical rich-club and structural-functional coupling in the human brain network. Cereb. Cortex 31 (4), 1987–1997 (2021).

Gu, Z. et al. Heritability and interindividual variability of regional structure-function coupling. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 4894 (2021).

Dehghan Nayyeri, M. et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of default mode network in brachioradial pruritus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 36 (11), 2214–2223 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of resting-state brain networks are associated with migraine disability. J. Headache Pain 24 (1), 13 (2023).

Fedeli, D. et al. Longitudinal neurofunctional changes in medication overuse headache patients after mindfulness practice in a randomized controlled trial (the MIND-CM study). J. Headache Pain 25 (1), 97 (2024).

Jalon, I. et al. Lesions to both somatic and affective pain pathways lead to decreased salience network connectivity. Brain 146 (5), 2153–2162 (2023).

Garcia-Larrea, L. & Peyron, R. Pain matrices and neuropathic pain matrices: A review. Pain 154 (Suppl 1), S29–s43 (2013).

Cauda, F. et al. Altered resting state attentional networks in diabetic neuropathic pain. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 81 (7), 806–811 (2010).

Cauda, F. et al. Altered resting state in diabetic neuropathic pain. PLoS One 4 (2), e4542 (2009).

Haggard, P., Iannetti, G. D. & Longo, M. R. Spatial sensory organization and body representation in pain perception. Curr. Biol. 23 (4), R164–R176 (2013).

Senkowski, D., Höfle, M. & Engel, A. K. Crossmodal shaping of pain: A multisensory approach to nociception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18 (6), 319–327 (2014).

Pomper, U. et al. Crossmodal bias of visual input on pain perception and pain-induced beta activity. Neuroimage 66, 469–478 (2013).

Cao, S. et al. Herpes zoster chronification to postherpetic neuralgia induces brain activity and grey matter volume change. Am. J. Transl. Res. 10 (1), 184–199 (2018).

Paquola, C. et al. Microstructural and functional gradients are increasingly dissociated in transmodal cortices. PLoS Biol. 17 (5), e3000284 (2019).

Medaglia, J. D. et al. Functional alignment with anatomical networks is associated with cognitive flexibility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2 (2), 156–164 (2018).

Vázquez-Rodríguez, B. et al. Gradients of structure-function tethering across neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (42), 21219–21227 (2019).

Baron, R., Binder, A. & Wasner, G. Neuropathic pain: Diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 9 (8), 807–819 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the participants of this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China(2022YFC3602202), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81960313), the Clinical Research Center For Medical Imaging In Jiangxi Province (No.20223BCG74001) and the Key research and development plans of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant No. S2020ZPYFB2343).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, S.H.; resources, J.J.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, J.J.; funding acquisition, L.G., J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study strictly adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (ethics approval code:20200145).

Informed consent

All participants provided informed written consent before participating and were able to understand the questionnaire in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Jiang, J., Jiang, X. et al. Abnormal alterations in structure-function coupling at the modular level in patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Sci Rep 15, 2377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86908-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86908-w

This article is cited by

-

Analysis of correlation between structural changes and functional response in post-stroke motor recovery after cM1 LF-rTMS: an exploratory randomized trial

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Genetically predicted the causal relationship between gut–brain axis and chronic pain: a Mendelian randomization study

Human Genomics (2025)