Abstract

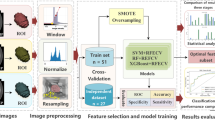

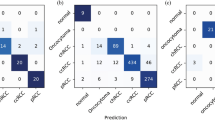

Eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma (ESC-RCC) is rare and often misdiagnosed as clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Therefore, a CT-based scoring system was developed to improve differential diagnosis. Retrospectively, 25 ESC-RCC and 176 ccRCC cases, were collected. The two groups were matched on a 1:2 basis using the propensity-score-matching (PSM) method, with matching factors including sex and age. Finally, 25 ESC-RCC and 50 ccRCC cases were included and randomly divided into a training cohort (52 cases) and a validation cohort (23 cases). Logistic regression identified significant factors, constructed the primary model, and assigned weights for the scoring model. Diagnostic performance was compared using receiver operating characteristic curves, dividing points into three intervals. Multifactorial logistic regression identified three independent factors: intra-tumour necrosis (3 points), degree of corticomedullary phase (CMP) enhancement (3 points), and pseudocapsule (2 points). The primary model’s area under the curve (AUC) value was 0.954 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.857–0.993, P < 0.001), with 85.7% sensitivity and 94.1% specificity. The scoring model’s AUC value for the training cohort was 0.950 (95% CI: 0.852–0.991, P < 0.001), with 77.1% sensitivity and 100% specificity at a cut-off of 4 points. The validation cohort’s AUC was 0.942 (95% CI: 0.759–0.997, P < 0.001). The scoring system intervals were: ≥0 to < 2 points, ≥ 2 to ≤ 3 points, and > 3 to ≤ 8 points. Higher scores correlated with increased ccRCC incidence and decreased ESC-RCC incidence.The limitation of this study is the small sample size. A CT-based scoring system effectively differentiates ESC-RCC from ccRCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma (ESC-RCC) is a rare and unique renal carcinoma, first named by Trpkov et al.1in 2016, characterised by cystic solid structures and cytokeratin 20 immunoexpression. In 2022, the World Health Organisation/International Society of Urological Pathology (WHO/ISUP) recognised it as a new type of distinct renal cell carcinoma (RCC) subtype due to its cystic solid morphology2. ESC-RCC exhibits indolent behaviour, a favourable prognosis, and infrequent recurrence or metastasis after surgery3. Its imaging shows a cystic solid mass with clear margins and a relatively rich blood supply, resembling clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), making preoperative differentiation challenging4. CCRCC, the most common RCC subtype, accounts for 70–80% of renal cancers, is more invasive, and has a poorer prognosis5 .

Multiphase contrast-enhanced CT is a convenient and rapid tool for diagnosing renal cancers, differentiating its subtypes, and predicting prognosis6,7. Given the significant differences in prognosis and treatment between ESC-RCC and ccRCC, it is crucial to distinguish between them accurately. Most previous investigators studying ESC-RCC had sample sizes of no more than ten cases, with most being single-center studies. In contrast, this study collected data from two centers, resulting in a sample size of 25 ESC-RCC cases. Additionally, studies on the differences in CT characteristics between these two subtypes of RCC are lacking in the literature. In this study, after propensity-score-matching (PSM) for sex and age between the two groups, a scoring system using preoperative multiphase contrast-enhanced CT was developed for the differential diagnosis of ESC-RCC and ccRCC. This system could serve as a valuable reference for clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and prognosis assessment.

Materials and methods

Patients

A retrospective collection of 25 cases of ESC-RCC and 176 cases of ccRCC definitively diagnosed by pathology from January 2019 to April 2024 was performed. To control for confounders, reduce study bias, and balance baseline differences between groups, the two groups were matched on a 1:2 basis, using sex and age as matching factors. Ultimately, 25 ESC-RCC cases (19 patients from Ningbo Medical Center LiHuiLi Hospital and six patients from the First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University) and 50 ccRCC cases (all from Ningbo Medical Center LiHuiLi Hospital) were enrolled. Inclusion criteria: (1) clear diagnosis by postoperative pathology; (2) preoperative multiphase contrast-enhanced CT. Exclusion criteria: (1) poor image quality; (2) prior interventional therapy (e.g., radiotherapy and chemotherapy); (3) previous history of renal cancer surgery. The ESC-RCC group comprised 12 males and 13 females, aged 26–84 years. The ccRCC group included 23 males and 27 females, aged 27–84 years. In both groups, most patients were asymptomatic and diagnosed through physical examination. Patients were randomly assigned to a training cohort (17 cases of ESC-RCC and 35 cases of ccRCC) and a validation cohort (8 cases of ESC-RCC and 15 cases of ccRCC) in a 7:3 ratio. This study was approved by the local medical ethics committee of the relevant medical unit (approval number: KY2023PJ169). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ningbo Medical Center LiHuiLi Hospital ethics committee waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Multiphase contrast-enhanced CT

All patients underwent imaging using a 256-row Revolution CT (GE Healthcare) and a 320-row CT (Toshiba Aquilion One). The scanning area extended from the upper pole of both kidneys to the lower edge of the pubic symphysis. Scanning parameters included a tube voltage of 120 kVp, a tube current of 250 mA, and a layer thickness and spacing of 5 mm. Enhancement scans were performed using a non-ionic contrast agent (Omnipaque 350 mg I/mL) injected into the middle cubital vein at a volume of 1.2–1.5 mL/kg and a rate of 2.5–3.0 mL/s. The renal corticomedullary phase (CMP), nephrographic phase (NP), and excretory phase (EP) scans were obtained at 25–30 s, 90–100 s, and 180 s after contrast injection, respectively.

CT features

The CT imaging findings were evaluated independently by two experienced radiologists specialising in abdominal disease diagnosis, who were blinded to the pathological findings. Any disagreements will be settled through consultation. Key observations included: (1) tumour characteristics, such as location (left/right kidney), solitary or multiple status, and maximum diameter; (2) tumour morphology (round with clear borders, lobulated with clear borders, or infiltrative with unclear borders) and the growth pattern of the tumour: tumour endogenous, < 50% extrarenal or ≥ 50% extrarenal; (3) unenhanced CT density of the solid tumour portion categorised as hypodense, slightly hyperdense (> 5 Hounsfield units different from the renal cortex), or isodense; tumour cystic changes (well-defined and morphologically regular areas of non-enhancement) were classified by the proportion of cystic to solid components (> 75% cystic, equal cystic-solid, or > 75% solid), and intra-tumour necrosis was identified by non-enhanced areas with unclear borders and irregular morphology. Additionally, the presence of a pseudocapsule (a low-density ring surrounding the tumour), calcifications, haemorrhage, etc.; (4) degree of CMP enhancement, categorised as lower or equal to/slightly higher than the renal cortex in the solid tumour portion; (5) enhancement pattern, either fast-in-fast-out (CMP enhancement followed by reduction in NP and further reduction in EP) or persistent enhancement (significant CMP enhancement without reduction in NP enhancement). CT values in the solid tumour portion, avoiding cystic changes, necrosis, and haemorrhagic areas, were measured twice within a 20 mm² region of interest, and the average was used for analysis. The κ coefficients were used to assess the agreement between two radiologists who independently evaluated the CT images of the two renal cancer types (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The analysis were performed using SPSS 27.0 and MedCalc 18.6. Nearest neighbour matching was used for 1:2 matching with a caliper value of 0.02. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality of continuous variables. Continuous variables following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and comparisons between groups were performed using independent samples t-tests. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages (%) and compared using the χ² test, the corrected χ² test, or Fisher’s exact test. The agreement between the results of the two observers was assessed using the κcoefficients. Data from the training cohort were used for model development. Due to the large number of variables, a univariate analysis was performed first. A multiple multicollinearity test was conducted for variables with one-way significance, followed by a multifactorial logistic backward stepwise analysis. Scores from the multifactorial analysis were determined based on the B-values from logistic regression using the formula by Ben et al.8 (B/Bmin×2, where B is the regression coefficient of each factor and Bmin is the minimum regression coefficient), rounding up to the nearest integer for the weight score of each factor. Independent factor scores were summed to obtain total points for each patient, forming the scoring model. Stability validation of the models was performed using the bootstrap and Lasso methods. ROC curves assessed the model’s diagnostic performance, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test evaluated the agreement between the predicted and actual probabilities. The Delong test compared the differences between the two models. Data points were categorised into three intervals for clinical applicability. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Before and after PSM in two groups

The male rate was 48% (12/25) in the ESC-RCC group and 60.8% (107/176) in the ccRCC group before PSM, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.223). After PSM, 48% of the ESC-RCC group and 46% of the ccRCC group were male, showing no statistically significant difference (P = 0.870). The mean age of the ESC-RCC group before PSM was (56.0 ± 15.9) years, while the ccRCC group had a mean age of (59.2 ± 11.8) years, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.338). After PSM, the mean age of the ESC-RCC group was (56.0 ± 15.9) years, and the ccRCC group had a mean age of (56.2 ± 12.6) years, again with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.934).

Comparison of CT features

All κ coefficients between the two observers were greater than 0.85, indicating high consistency. Theκcoefficients for the variables intra-tumour necrosis, pseudocapsule, and degree of CMP enhancement were all greater than 0.92, indicating extremely high consistency (Table 1). In the training cohort, both types of renal cancer were solitary. There were no statistically significant differences between the two types in terms of maximum diameter, location, growth pattern, morphology and boundaries, cystic changes, calcification and haemorrhage (P > 0.05). On unenhanced CT scans, 70.6% of ESC-RCC cases appeared slightly hyperdense, whereas most ccRCC cases were isodense or hypodense. Only one case of ESC-RCC showed intra-tumour necrosis, with a pseudocapsule present in 23.5% of cases. In contrast, intra-tumour necrosis was observed in 65.7% of ccRCC cases, with a pseudocapsule present in 74.3% of cases. In addition, 88.2% of ESC-RCC cases showed CMP enhancement lower that of the renal cortex, with most showing persistent enhancement. In ccRCC, 68.6% of cases showed a degree of CMP enhancement equal to or slightly higher than that of the renal cortex, with a pattern of fast-in and fast-out enhancement. The comparison of CT findings between ESC-RCC and ccRCC revealed statistically significant differences in five factors: unenhanced CT density, intra-tumour necrosis, degree of CMP enhancement, pseudocapsule, and enhancement pattern (P < 0.05, Table 2. Representative diagrams are presented in Figs. 1 and 2.

A 69-year-old man presented with a round, well-defined mass approximately 3.5 cm in diameter located in the lower pole of the left kidney. Another small non-enhancing cyst in the left kidney. On the unenhanced CT, the solid portion of the tumour appears slightly hyperdense (A). In the corticomedullary phase, the solid component of the tumour shows greater enhancement compared to the renal cortex (B, 3 points), with necrotic components of irregular morphology indicated (red arrow, 3 points). The enhancement in the nephrographic phase is reduced and lower than that in the renal cortex (C). The tumour exhibits a fast-in-fast-out enhancement pattern, with a pseudocapsule surrounding the tumour (yellow arrow, 2 points). The total score of 8 points in this case strongly suggested clear cell renal cell carcinoma, which was confirmed by the final pathological findings.

A 38-year-old man with a round, well-circumscribed and predominantly solid mass of approximately 4 cm in diameter in the lower pole of the right kidney. On unenhanced CT the tumour exhibited a slightly high density (A). In the corticomedullary phase, the solid portion of the tumour demonstrated less intense enhancement compared to the renal cortex (B, 0 points). In the nephrographic phase, the enhancement persisted but remained lower than the renal cortex (C). The tumour was homogeneous in density, with no necrotic components observed (0 points), and displayed a persistent enhancement pattern without a surrounding pseudocapsule (0 points). The total score of 0 points strongly indicated eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma, which was confirmed by the final pathological findings.

Building the primary model

The variance inflation factors (all < 10) and tolerances > 0.1 for the five factors identified in the univariate analysis indicated no multicollinearity. Multifactorial logistic regression analysis identified three statistically significant factors: intra-tumour necrosis (odds ratio [OR] = 72.587; 95% CI: 4.032–1306.820; P = 0.004), degree of CMP enhancement (OR = 29.130; 95% CI: 2.541–333.882; P = 0.007), and pseudocapsule (OR = 13.734; 95% CI: 1.347–140.004; P = 0.027). These factors independently distinguished ESC-RCC from ccRCC, forming the primary model (Table 2). The Hosmer–Lemeshow confirmed a good model fit (P = 0.974). The primary model achieved an AUC of 0.954 (95% CI: 0.857–0.993, P < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 94.1%.

Building the scoring model

Points were assigned based on the regression coefficient B values from the multifactorial logistic regression analysis: intra-tumour necrosis (3 points), degree of CMP enhancement (3 points), and pseudocapsule (2 points), resulting in a score range of 0 to 8 points. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated a good fit for the scoring model (P = 0.884). The AUC for the scoring model in the training cohort was 0.950 (95% CI: 0.852–0.991, P < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 77.1% and a specificity of 100% at a cut-off value of 4 points. The Delong test showed no significant difference between the primary and scoring models (Z = 0.664, P > 0.05), suggesting high compatibility between the models (Fig. 3). The positive and negative likelihood ratios of the scoring system are provided in the supplementary material (Table S1).

Validation of the scoring model

To facilitate clinical assessment and application, the final scores were divided into three intervals: ≥0 to < 2 points, ≥ 2 to ≤ 3 points, and > 3 to ≤ 8 points. As the score increases, the incidence of ESC-RCC decreases while the incidence of ccRCC increases. In the three score intervals, the incidence of ESC-RCC was 90.9% (10/11), 50.0% (7/14), and 0% (0/30), respectively. In the validation cohort, which included eight cases of ESC-RCC and 15 cases of ccRCC, the incidence of ESC-RCC was 100% (4/4), 57.1% (4/7), and 0% (0/12) in the three intervals, respectively (Table 3). The AUC value for the validation cohort was 0.942 (95% CI: 0.759–0.997, P < 0.001), indicating high predictive accuracy. The stability of the model was verified using the bootstrap method (AUC of 0.928 for the training cohort and 0.917 for the validation cohort) and the Lasso method (AUC of 0.934 for the training cohort and 0.925 for the validation cohort). These results are similar to those of this study, suggesting that the model is stable.

Discussion

RCC is a malignant tumour originating from the renal tubule epithelium, recognised as one of the more malignant tumours in the urological tract9. ccRCC is the most prevalent pathological subtype of RCC, whereas ESC-RCC is a rare and newly recognised subtype, comprising approximately 0.2% of renal epithelial tumours10. Imaging, particularly multiphase contrast-enhanced CT scans—including CMP, NP, and EP—is crucial for identifying RCC subtypes. These scans provide comprehensive imaging features of RCC, aiding early diagnosis, staging, grading, treatment selection, and prognosis assessment11,12. Some researchers have developed CT-based scoring systems to differentiate between ccRCC and angiomyolipoma without visible fat, achieving an AUC of 0.978 in the training cohort for predicting ccRCC13. In this study, two types of renal cancers were matched 1:2 for sex and age and multiphase contrast-enhanced CT was used to develop a scoring model for distinguishing between ccRCC and ESC-RCC. This scoring model is simple, easy to implement, and practical, making it convenient for radiologists and clinicians.

In this study, 75 cases of ccRCC and ESC-RCC were randomly divided into a.

training cohort and a validation cohort. In the training cohort, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identified intra-tumour necrosis, the degree of CMP enhancement, and pseudocapsule as statistically significant factors distinguishing between the two renal cancer types (P < 0.05). These three independent factors were deemed critical CT features for differentiating ccRCC from ESC-RCC. The primary model achieved an AUC of 0.954, with a sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 94.1%, indicating high diagnostic efficacy. To further refine diagnostic accuracy, In this study, the three independent factors—intra-tumour necrosis, degree of CMP enhancement, and pseudocapsule—were assigned points based on their B-values to construct a scoring model ranging from 0 to 8 points. This scoring model achieved an AUC of 0.950, with a cut-off value of 4 points, demonstrating a sensitivity of 77.1% and a specificity of 100%. The close alignment of the diagnostic efficacy between the scoring model and the primary model underscores the scoring model’s robustness and suitability for clinical application. Moreover, the AUC value for the validation cohort was exceptionally high at 0.942, demonstrating minimal deviation from the AUC values of both the primary and scoring models. This consistency suggests that the scoring model is not only highly effective for distinguishing the two renal cancer types but also exhibits excellent generalisability, making it a valuable tool for clinical use. After bootstrap and Lasso validation, the AUCs of the training and validation cohorts were similar to those of this study, indicating that the model is stable and worthy of clinical application.

The present study further revealed that within the first scoring interval (≥ 0 to < 2 points), the incidence of ESC-RCC was 90.9% and 100% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively. This interval strongly indicated a predilection for diagnosing ESC-RCC, with very few cases of ccRCC when all three independent factors scored 0 points. Conversely, in the third interval (> 3 to ≤ 8 points), the incidence of ESC-RCC was 0% in both cohorts, indicating that all cases in this interval were diagnosed as ccRCC. As the score increased within this interval, indicating the positive expression of at least two independent factors, the diagnosis increasingly favoured ccRCC. Overall, as the total points increased from the first to the third interval, there was a corresponding increase in the incidence of ccRCC and a decrease in the incidence of ESC-RCC. These findings underscore the effectiveness of the scoring model in differentiating between ESC-RCC and ccRCC based on the identified CT imaging features.

In this study, the presence of necrotic components within the tumour emerged as the most crucial independent factor for distinguishing between the two types of renal cancer, with an OR value of 72.587. The presence of necrotic components was strongly indicative of ccRCC. In the training cohort, necrotic components were observed in 65.7% of ccRCC cases. Due to the unstable biological behaviour of ccRCC, characterised by high invasiveness and rapid growth, the tumour’s increased neovascularisation cannot meet its growth and metabolic demands, resulting in inadequate internal blood supply and the appearance of necrotic components with irregular morphology and unclear borders. In contrast, necrosis was observed in only one case of ESC-RCC, and the diameter of this tumour was 11.5 cm, the largest among the 25 cases of ESC-RCC. Research indicates that when the diameter of ESC-RCC exceeds 10 cm and necrosis is present, the tumour’s malignancy increases, making it more prone to recurrence and metastasis after surgery10. Furthermore, studies have validated intratumoural necrosis as an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in ccRCC, providing significant prognostic information that complements the WHO/ISUP classification of renal cancer14,15. This highlights the critical role of intra-tumour necrosis in assessing the aggressiveness and potential clinical outcomes of renal tumours.

The findings of this study demonstrated that the degree of CMP enhancement (OR = 29.130) was a significant independent factor in differentiating between the two renal cancer types. In the training cohort, 68.6% of ccRCC cases exhibited CMP enhancement equal to or greater than that of the renal cortex, while 31.4% showed CMP enhancement lower than that of the renal cortex. Conversely, 88.2% of patients with ESC-RCC exhibited CMP enhancement lower than that of the renal cortex. ccRCC is characterised by a rich blood supply and typically displays a “fast-in-fast-out” enhancement pattern. The degree of CMP enhancement in ccRCC is associated with the structural parameters of the microvasculature, including density, area, diameter, and circumference, as well as tumour haemodynamics16. Coy H et al.17found that the degree of early CMP enhancement in ccRCC was positively correlated with MVD and closely related to WHO/ISUP grading: lower-grade ccRCCs have higher microvessel density (MVD) and thus higher CMP enhancement. Consequently, lower-grade ccRCCs tend to show significant enhancement equal to or higher than that of the renal cortex. In this study, 50 patients with ccRCC after PSM were included. In the randomly assigned training cohort, low-grade ccRCC was predominant and showed CMP enhancement that was slightly higher than or equal to the renal cortex (68.6% of cases). In contrast, ESC-RCC is less vascularised than ccRCC and typically exhibits a lower degree of CMP enhancement compared to the renal cortex (88.2% of cases), often exhibiting “persistent enhancement”4. This difference in enhancement patterns might be attributed to variations in microvascular structure and haemodynamics between the two renal cancer types, warranting further investigation.

Most scholars believe that the pseudocapsule in renal cancer is a fibrous membrane structure comprising collagen fibres and smooth muscle bundles, formed due to the outward growth and compression of the surrounding renal parenchyma during tumour development. The pseudocapsule is considered a hallmark of renal malignancy18. In this study, the presence of a tumour pseudocapsule was identified as an independent factor in differentiating between the two RCC types, with an OR of 13.734. Specifically, a pseudocapsule was present in 74.3% (26/35) of ccRCC cases, suggesting that the diagnosis of a pseudocapsule strongly favours ccRCC. Pathologically, ESC-RCC is characterised by cystic-solid components and lacks the peripheral structures around the tumour19. On CT imaging, a pseudocapsule was present in only 23.5% (4/17) of ESC-RCC cases in the training cohort. ESC-RCC grows expansively with inert biological behaviour, resulting in slower growth and less pressure on the surrounding renal tissue. This might account for the lower incidence of pseudocapsule formation compared to other renal cancer types.

This study has several limitations. Being retrospective, it introduces the possibility of selection bias. The low incidence of ESC-RCC and the small sample size also limit the study’s generalisability and may impact the stability of the model, highlighting the need for a subsequent prospective study with a larger cohort for validation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, intra-tumour necrosis, the degree of CMP enhancement, and the presence of a pseudocapsule are independent factors for differentiating ESC-RCC from ccRCC after PSM for sex and age in the two groups. A scoring model based on these three CT features is simple, convenient, and demonstrates high diagnostic efficacy. In clinical practice, this scoring system could be valuable for radiologists and clinicians, facilitating a more accurate preoperative diagnosis. This, in turn, aids in selecting appropriate treatment options and assessing the prognosis for patients with renal tumours.

Data availability

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Trpkov, K. et al. Eosinophilic, solid, and cystic renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 16 unique, sporadic neoplasms Occurring in Women. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40 (1), 60–71 (2016).

Moch, H. et al. The 2022 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-Part A: renal, Penile, and testicular tumours. Eur. Urol. 82 (5), 458–468 (2022).

Kamboj, M. et al. Eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma: a rare under-recognized indolent entity. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 64 (4), 799–801 (2021).

Fu, S. et al. Analysis of imaging and pathologic features in Eosinophilic Solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 22 (4), 102124 (2024).

Warren, A. Y. & Harrison, D. WHO/ISUP classification, grading and pathological staging of renal cell carcinoma: standards and controversies. World J. Urol. 36 (12), 1913–1926 (2018).

Al Nasibi, K. et al. Development of a multiparametric renal CT algorithm for diagnosis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma among Small (= 4 cm) solid renal Masses</at. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 219 (5), 814–823 (2022).

Nie, P. et al. A CT-based deep learning radiomics nomogram outperforms the existing prognostic models for outcome prediction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 33 (12), 8858–8868 (2023).

Ben, A. H. et al. Performance of an easy and simple New Scoring Model in Predicting Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Community-acquired urinary tract infections. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 6 (4), ofz103 (2019).

Bahadoram, S. et al. Renal cell carcinoma: an overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. G Ital. Nefro. 39 (3), 2022–vol3 (2022).

Yi, M. et al. Eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma: a review of literature focused on radiological findings and differential diagnosis. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 48 (1), 350–357 (2023).

Zheng, Z., Chen, Z., Xie, Y., Zhong, Q. & Xie, W. Development and validation of a CT-based nomogram for preoperative prediction of clear cell renal cell carcinoma grades. Eur. Radiol. 31 (8), 6078–6086 (2021).

Mahootiha, M., Qadir, H. A., Bergsland, J., Zhong, Q. & Xie, W. Multimodal deep learning for personalized renal cell carcinoma prognosis: integrating CT imaging and clinical data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 244, 107978 (2024).

Wang, X. J. et al. A non-invasive scoring system to Differential diagnosis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) from renal Angiomyolipoma without visible Fat (RAML-wvf) based on CT features. Front. Oncol. 11, 633034 (2021).

Khor, L. Y. et al. Tumor necrosis adds prognostically significant information to Grade in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: a study of 842 consecutive cases from a single Institution. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40 (9), 1224–1231 (2016).

Syed, M. et al. Prognostic significance of percentage necrosis in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 157 (3), 374–380 (2022).

Ouyang, A. M. et al. Relative computed tomography (CT) enhancement value for the Assessment of Microvascular Architecture in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 23, 3706–3714 (2017).

Coy, H. et al. Association of tumor grade, enhancement on multiphasic CT and microvessel density in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 45 (10), 3184–3192 (2020).

Dong, X. et al. Characteristics of peritumoral pseudocapsule in small renal cell carcinoma and its influencing factors. Cancer Med. 12 (2), 1260–1268 (2023).

Trpkov, K. et al. Eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma (ESC RCC): further morphologic and molecular characterization of ESC RCC as a distinct entity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 41 (10), 1299–1308 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript. Thanks to Xiao Yu for clinical and technical support, Philips Healthcare.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuqin Zhang and Dawei Chen: Methodology, Writing–original draft. Sunya Fu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. Yuguo Wei: Data curation, Writing–original draft. Yuning Pan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing–review & editing. All authors contributed to the study conception and design.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Ningbo Medical Center LiHuiLi Hospital ethics committee (approval number: KY2023PJ169). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ningbo Medical Center LiHuiLi Hospital ethics committee waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Authorship

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, S., Chen, D., Zhang, Y. et al. CT-based scoring system for diagnosing eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma versus clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 2736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86932-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86932-w