Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains a significant global public health issue with high mortality rates and challenges posed by drug-resistant strains, emphasizing the continued need for new therapeutic targets and effective treatment strategies. Transcriptomics is a highly effective tool for the development of novel anti-tuberculosis drugs. However, most studies focus only on changes in gene expression levels at specific time points. This study screened for genes with altered expression patterns from available transcriptomic data and analysed their association with the TB progression. Initially, a total of 1228 genes with altered expression patterns were identified through two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We define genes with a P-value less than 0.05 for the combined effect of infection and time on gene expression as those with altered expression patterns. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that the biological functions of these genes mainly involve DNA translation, RNA processing, and transcriptional regulation. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis indicated that these genes are primarily associated with fatty acid degradation, pyruvate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, as well as cholesterol metabolism signaling pathways. Subsequent Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis identified four core genes closely associated with TB progression, namely Rac Family Small GTPase 1 (RAC1), Ring-Box 1 (RBX1), Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L33 (MRPL33), and ELAV Like RNA Binding Protein 1 (ELAVL1). Q-PCR experiments confirmed that Mtb infection led to changes in the gene expression patterns of RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL1 in THP-1 cells. These four genes may serve as core biomarkers for TB progression and can be utilized in the development of more effective anti-tuberculosis drugs and host therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), a severe infectious disease caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), has an annual global incidence of up to 7.5 million new cases. If left untreated, TB can result in a mortality rate of up to 50%, making it one of the leading infectious cause of death worldwide. Despite the existence of numerous effective anti-tuberculosis drugs, TB remains a significant global public health issue1,2. Moreover, the emergence of drug-resistant TB poses a significant challenge to healthcare resources, particularly in developing countries, where the high mortality rate and economic burden associated with drug-resistant TB have become serious issues3,4. Mtb has developed resistance to almost all anti-tuberculosis drugs, including the new drug bedaquiline5,6. Therefore, there is still a need to develop novel therapeutic targets and to pursue research on more effective anti-tuberculosis drugs and treatment strategies.

Transcriptomics, as an emerging discipline that studies the overall cellular gene transcription and regulatory patterns, plays a crucial role in the discovery of new antimicrobial targets7. In the development of anti-tuberculosis drugs, the application of transcriptomics aids in the identification of potential targets, the discovery of new drug targets, the evaluation of drug efficacy, and the achievement of personalized treatment, thereby accelerating the drug development process8. Moreover, transcriptomics is widely applied in the identification of drug-resistant targets in Mtb9. By analyzing the gene expression patterns in bacteria in-depth, transcriptomics provides researchers with a more comprehensive and effective approach, supporting the improvement of diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases such as TB8,10.

In the research process, researchers frequently concentrate on the upregulation or downregulation of genes at certain time points, overlooking the temporal factor and the alterations in gene expression patterns11. This approach may lead to a biased study and make it difficult to identify core biomarkers that drive disease progression. Therefore, this study pioneered the comparison of the trends in gene expression over time between two cell groups in transcriptomics, with the objective of identifying genes with altered expression patterns and associate them with disease progression, thus selecting core gene biomarkers that promote the occurrence and development of TB. This study is expected to identify core biomarkers that drive TB progression and provide a solid theoretical basis for the development of more effective anti-tuberculosis drugs and treatment strategies.

Materials and methods

Data sources

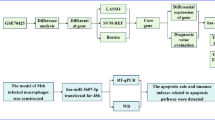

The original gene expression profiles (GSE112104, GSE108731) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The workflow of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Analysis of gene sets with altered expression patterns

The curve graph depicting the expression levels of all genes in GSE108731 as a function of infection time was generated using the “ggplot2” package and “dplyr” package in R. Genes with significant changes in expression patterns were identified through variance analysis. Specifically, genes with a combined infection and time effect P-value of less than 0.05 were preliminarily considered as genes with altered expression patterns.

Enrichment analysis of Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways in gene sets with altered expression patterns

The GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05. The GO analysis encompassed cellular component (CC), biological process (BP), and molecular function (MF) categories.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis of gene sets with altered expression patterns

The PPI network was established utilizing the STRING database (http://string-db.org). Subsequently, the Hubba plugin in Cytoscape (3.9.1) was employed for the analysis and identification of the highest-ranking hub genes, based on their respective scores.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

The diagnostic utility of hub genes in GSE112104 was evaluated by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) using ROC curve analysis. Clinical information of GSE112104 was provided in Supplementary File 3. Gene expression data from the “pROC” package was employed for this evaluation. Candidate genes were identified based on an AUC threshold of greater than 90%.

Immune infiltration analysis

The proportions of 28 immune cells in the samples of the GSE112104 dataset were obtained from an online website (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/data/download/CellReports.txt) and provided in Supplementary File 2. Box plots depicting the levels of immune cell infiltration between progressive and non-progressive infections, as well as a heatmap for correlation analysis, were generated with the “ggplot2” and “pheatmap” package.

Macrophage polarization

The THP-1 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection, (ATCC) (ATCC-TIB-202). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Logarithmic phase cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells per well. THP-1 cells were differentiated into naïve (M0) macrophages by the treatment with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma) for 24 h.

H37Ra infection of macrophages

H37Ra strain was cultured in 7H9 medium until logarithmic phase. M0 macrophages were then infected with H37Ra at an MOI of 10 and sequentially incubated for 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 48 h. The control group received a similar volume of PBS. At each time point, the cells were harvested and subjected to three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove extracellular bacteria for subsequent experiments. Each time point was performed in triplicate experiments.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from macrophages with the UNIQ-10 column-based total RNA extraction kit (Sangon Biotech, China). The mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the EasyScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis kit. Q-PCR was performed in a 96-well qPCR-specific plate using the TransStart® Tip Green q-PCR SuperMix. GAPDH served as the housekeeping gene in this experiment, with uninfected THP-1 cells at each time point designated as the control group. The relative expression levels of the genes were calculated using the 2 − ΔΔCT method. The q-PCR oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 1. Each time point was performed in triplicate experiments.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for multiple comparisons, and paired t-tests were used to determine the P-values for two-sample data. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, where P-values were assigned as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Results

Identification of pattern change genes between normal M0 and M0 infected with H37Ra

The GSE108731 database was downloaded, which included the mRNA expression levels of M0 macrophages in the infected group and control group at 1, 4, 12, 24, and 48 h after infection. Subsequently, a two-way ANOVA was performed to investigate the impact of infection and time on gene expression levels. Genes that showed a combined effect of infection and time on expression levels were temporarily designated as genes with altered expression patterns, and a total of 1228 genes with altered expression patterns were identified. Temporal changes in the gene expression levels for these genes were then depicted in line graphs. A small part of the line graphs and ANOVA results are shown in Fig. 2, while the line graphs and ANOVA results for all 1228 genes are provided in Supplementary File 1.

Gene expression in THP-1 macrophages after Mtb infection. The downloaded GSE108731 data was subjected to secondary analysis. R language packages “dplyr” and “broom” were used to perform two-way ANOVA on all downloaded genes. Genes with a P-value less than 0.05, indicating a joint effect of infection and time on gene expression, were considered as genes with altered expression patterns. The “ggplot2” and “dplyr” packages were used to plot the curve of gene expression changes over time

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of genes with altered expression patterns

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were applied for identification of 1228 genes with altered expression patterns to determine their potential functions involved in Mtb infection. The GO-MF enrichment analysis of these genes revealed that their molecular functions are primarily associated with protein binding, identical protein binding, RNA binding, and RNA polymerase II core promoter proximal region sequence-specific DNA binding (Fig. 3C). The GO-BP enrichment analysis of these genes showed that their biological processes mainly involve regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, RNA processing, regulation of transcription, and DNA-templated (Fig. 3A). The GO-CC enrichment analysis of these genes identified that they were involved in the cellular components related to cytosol, mitochondrion, nucleolus, and chromatin (Fig. 3B). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of these genes indicated that they were associated with signaling pathways such as lysosome, fatty acid degradation, pyruvate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and cholesterol metabolism (Fig. 3D).

Identification of hub genes

To determine the interactions between genes exhibiting altered expression patterns in response to Mtb infection, a PPI analysis was conducted on 1228 differentially genes. The PPI networks were further analyzed using the CytoHubba plugin to identify hub genes. Figure 4B presents a bar graph of the top 40 ranked proteins based on their interaction scores, while Fig. 4A shows the PPI network of the top 40 genes ranked by degree. These 40 genes were initially identified as hub genes.

ROC curve analysis

The expression data from peripheral blood samples of 16 patients with progressive tuberculosis and 21 healthy individuals infected with Mtb (GSE112104) were analysed. These data were used to perform ROC curve analysis on the aforementioned hub genes in order to further validate their relevance to TB progression (Fig. 5). Hub genes with AUC > 90% may exhibit excellent specificity and sensitivity for validation in future experiments, including Rac Family Small GTPase 1 (RAC1), Ring-Box 1 (RBX1), Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L33 (MRPL33), and ELAV Like RNA Binding Protein 1 (ELAVL1).

Immune infiltration analysis and correlation analysis

In the GSE112104 dataset, compared to non-progressors, individuals with progressive Mtb infection exhibited decreased relative abundance of Type 2 T helper cells, T follicular helper cells, neutrophils, natural killer cells, immature dendritic cells, mast cells, macrophages, gamma delta T cells, effector memory cluster of differentiation (CD)4 T cells, CD56bright natural killer cells, activated dendritic cells, and activated CD8 T cells (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B demonstrates a significant positive correlation between macrophages and RAC1, RBX1, and MRPL33, while monocytes and ELAVL1 displayed a negative correlation. Therefore, we will assess the expression of these four key genes in THP-1 macrophages through q-PCR.

Immune infiltration analysis was performed. A Box plots depicting the differential immune cell infiltration between progressive Mtb-infected patients and non-progressor healthy individuals. The P-values between the two sample groups were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, where *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. B Heatmap illustrating the correlation between M0-Hub and the 28 immune cells.

Validation of key mode changed gene expression levels in THP-1 macrophages infected with H37Ra

The q-PCR was performed to explore the expression of RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL1 in the two groups (Fig. 7). In THP-1 macrophages, Mtb infection resulted in altered expression patterns of RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL1 (time × treatment P < 0.05). The expression level of RBX1 in the infection group was significantly higher than that in the control group at 8, 12, and 16 h, while the expression level of MRPL3 in the infection group was significantly elevated compared to the control group at 4 and 8 h. Except at 16 h, the expression level of RAC1 in the infection group was significantly higher than that in the control group at all other time points. Infection of THP-1 cells with H37Ra resulted in a significant increase in ELAVL1 expression at 4, 8, 24, and 48 h (All P < 0.05).

The expression of hub genes in THP-1 macrophages following Mtb infection. The expression of hub genes was measured by q-PCR in M0 macrophages collected at 4-hour intervals within 24 h. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All data met the requirements for two-way analysis of variance and wilcoxon test (Each group has a sample size of 3). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, *Significant at P < 0.05, ***Significant at P < 0.001 and ****Significant at P < 0.0001

Discussion

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), TB remains one of the major global health threats1. Despite the availability of anti-tuberculosis drugs and known targets, the continued development of new targets is crucial. This will help address drug resistance issues, improve treatment efficacy, reduce side effects, increase treatment durability, and deepen understanding of the mechanisms of TB, thus promoting research progress12,13,14. Transcriptomics is an indispensable and extremely important tool for developing new therapeutic targets for TB8. In this study, we conducted a secondary analysis of existing transcriptomic data to fully explore valuable information within the data. We identified 1228 genes with altered expression patterns in THP-1 macrophages following Mtb infection through two-way ANOVA. GO enrichment analysis showed these genes are related to DNA translation, RNA processing, and transcriptional regulation. KEGG analysis revealed these genes are associated with fatty acid degradation, pyruvate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and cholesterol metabolism signaling pathways. Through PPI analysis and ROC curve analysis, 4 hub genes (RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL) that are closely associated with the progression of TB were obtained. Finally, q-PCR validation revealed that the relative expression levels of these 4 genes were generally elevated in Mtb-infected THP-1 macrophages for the majority of the time, and their expression patterns were altered compared to the control group.

The protein encoded by the RAC1 gene is a Guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) belonging to the RAS superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins, which regulates cellular processes such as cell growth, cytoskeletal reorganization, and protein kinase activation. This gene exists in two transcript variants encoding different isoforms and is associated with the third most prevalent protein hotspot mutation in melanoma, RAC1 P29S15,16. Limited studies have revealed the relationship between RAC1 and mycobacterium. According to one study, infection of airway epithelial cells with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) upregulated RAC1, leading to actin redistribution and suppression of inflammatory response via C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor (CXCR)1 and CXCR217. Actin polymerization resulted in membrane folding and ruffling, facilitating the engulfment of bacteria and surrounding extracellular fluid into the cells. However, blocking these G protein-coupled receptors prior Mtb infection abolished the actin redistribution induced by Mtb and the inhibition of NF-kappa-B (NF-κB)17,18. These results suggested that BCG may invade host cells and inhibit inflammatory response through manipulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Integrins are widely expressed adhesion receptors involved in cell migration and are associated with bacterial adhesion and cytoskeletal rearrangement19. Among them, β1 integrin mediates Mtb invasion of macrophages and controls granuloma formation through cell fusion mechanisms. Studies have shown that BCG infection activates β1 integrin and Rac1 on the surface of macrophages, leading to macrophage migration and granuloma formation. RAC1 is connected to β1 integrin, and its activation can affect cell adhesion, migration, and signal transduction, thereby regulating granuloma formation and the survival of Mtb20,21. However, another study found that Mtb nucleoside diphosphate kinase (Ndk) interacts with Rac1 and inactivates it, resulting in NADPH Oxidase (NOX)2 assembly defects. NOX2 assembly transfers electrons from cytoplasmic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to phagosome oxygen, contributing to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other superoxides22. As a conclusion, Mtb may promote host cell invasion, macrophage migration, and granuloma formation, while inhibiting the production of ROS by manipulating the activity of RAC1.The results of this study indicate that THP-1 macrophages infected with H37Ra alters the expression pattern of RAC1 and is closely associated with disease progression caused by Mtb infection. Therefore, RAC1 is likely to be a crucial puppet gene manipulated by Mtb in host macrophages, and Mtb may promote TB progression by activating the activity of RAC1.However, studies on this topic are very limited. In the future, we should further design experiments to validate the important role and specific mechanisms of RAC1 in Mtb infection and granuloma progression, as well as to screen RAC1 inhibitors and evaluate their therapeutic efficacy.

RBX1 is a protein containing a RING finger-like domain and serves as an E3 ubiquitin ligase component of multiple cullin-RING-based E3 ubiquitin ligase (CRLs) complexes. It mediates ubiquitination and subsequent protein degradation of target proteins, participating in the regulation of cell cycle progression, signal transduction, transcription, and transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair, among other biological processes23,24. A study of Mycobacterium avium infection of human macrophages indicated that Kelch Like ECH Associated Protein 1 (Keap1) was recruited to phagosomes in large quantities. Keap1, as part of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex with Cul3 and RBX1, promotes ubiquitination and degradation of IκB kinase (IKK)-β, thereby facilitating the intracellular growth of Mycobacterium avium. IKK-β initiates inflammatory responses and promotes the production of interferon (IFN)s25. In another experiment on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, it was found that the SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF10 hijacks E3 ubiquitin ligases containing Cullin-2, RBX1, ZYG11B to ubiquitinate and degrade host cell antiviral proteins26. Therefore, we speculate that when Mtb infects host macrophages, Mtb and its virulent molecules may also modulate RBX1 to degrade inflammation-related proteins to ensure their own survival. This view is supported by our findings that Mtb infection changes the expression pattern of RBX1 gene in THP-1 macrophages. Currently, there are no studies linking RBX1 to TB, which is regrettable because ubiquitination and degradation are important areas of research. Pathogens often manipulate ubiquitination to degrade inflammatory proteins, ultimately to achieve immune evasion27. Therefore, inhibiting the expression of RBX1 may enhance the inflammatory response against the pathogen. The design and development of antibodies targeting ubiquitination could open up a new direction for immunotherapy against TB, with RBX1 being a valuable core biomarker.

ELAVL1, a member of the ELAVL RNA-binding protein family, selectively binds to AU-rich elements (AREs) in the 3’ untranslated region of mRNA to promote the stability of ARE-containing mRNA and participate in the regulation of gene expression. It plays a role in various biological processes. Additionally, ELAVL1 acts in a pleiotropic manner in inflammation by interacting with specific mRNA subsets and negative transcriptional regulators, playing an essential role in the immune response of mice, and interacting with mRNA encoding various immune factors such as CD3, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Interleukin (IL)-3, IL-4, and IL-1328,29,30. There has been no research on the association between ELAVL1 and Mtb, making it a novel biomarker. Only one study has explored the role of ELAVL1 in anti-infection. This study found that Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment significantly induced the expression of ELAVL1 in zebrafish. ELAVL1b can directly kill both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria by inducing membrane depolarization and intracellular ROS generation. ELAVL1 may also act as a pattern recognition receptor, binding to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and their characteristic molecules, including LPS and lipopeptides31. It is found in this study that Mtb infection alters the expression pattern of the ELAVL1 gene in THP-1 macrophages, with higher levels of ELAVL1 expression in the infected group. This may be a host cell’s own anti-infection response. The abundant production of ELAVL1 may be used to activate more inflammatory factors and generate more ROS to eliminate invading pathogens. Accordingly, ELAVL1 deserves to be developed as an anti-TB and other infections drug. There is a possibility that in the future, we can further explore and validate the special role of ELAVL1 in anti-Mtb infection and optimize the structure and function of ELAVL1 protein to develop more effective anti-tuberculosis drugs.

This study also revealed that Mtb infection in THP-1 macrophages leads to altered expression patterns of the MRPL33 gene which encodes a mitochondrial ribosomal protein involved in protein synthesis within the mitochondria, belonging to the 39 S subunit protein32. Currently, there is a lack of research on the involvement of MRPL33 in infectious diseases, which presents a novel research direction. Previous studies have shown that immune cells enhance mitochondrial protein synthesis, promoting immune response against pathogens33. Enhanced immune response is concomitant with increased cellular metabolic activity34, consistent with the enrichment of metabolic pathways observed in KEGG enrichment analysis. Therefore, we hypothesised that Mtb infection in macrophages may enhance their own immune response, which requires more active mitochondrial protein synthesis. In fact, many antibacterial drugs, such as rifampicin, act by targeting bacterial ribosomal protein synthesis35. However, these drugs may also inhibit mitochondrial translation in immune cells, leading to toxic side effects and drug resistance. Thus, the upregulation of MRPL33 expression may alleviate the toxic side effects of antibiotics and decrease the development of drug resistance. MRPL33 may serve as a valuable target for studying the toxic side effects and drug resistance mechanisms of anti-tuberculosis drugs, as research in this area is currently lacking.

Currently, the antibiotic treatment of TB is limited by widespread drug resistance and a range of adverse effects36,37. Host-directed therapy effectively compensates for the shortcomings of existing antibiotic treatments by reducing pulmonary inflammatory damage, shortening treatment duration, and lowering the cytotoxicity of conventional chemotherapeutics while simultaneously minimizing resistance and promoting synergistic interactions with antibiotics13,14,38. In this study, four genes (RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL1) identified exhibited AUC values greater than 90%, indicating a close association with the progression of TB. These four host cell-targeted genes possess significant potential for the development of novel host-directed therapies for the treatment of TB, particularly multidrug-resistant strains.

This study has certain limitations. On one hand, due to experimental constraints, we were unable to validate our findings using the H37Rv strain. On the other hand, we did not manage to collect a larger clinical sample for validation and ROC analysis, nor could we conduct in-depth mechanistic studies or animal experiments. In future work, we plan to collect macrophages from clinical patients for validation and analysis, and to perform more comprehensive mechanistic investigations and animal studies.

Summary

In this study, a secondary analysis of existing transcriptomic data was conducted to reveal the altered gene expression patterns in THP-1 macrophages following Mtb infection. A total of 1228 genes with altered expression patterns were identified through two-way ANOVA. Enrichment analysis indicated that these genes are involved in DNA translation, RNA processing, transcriptional regulation, as well as fatty acid degradation, pyruvate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and cholesterol metabolism signaling pathways. Through PPI analysis and ROC curve analysis, four core genes (RAC1, RBX1, MRPL33, and ELAVL) that are strongly associated with TB progression were identified and subsequently validated using q-PCR. Inhibition of RAC1 expression can attenuate the invasion of Mtb into host cells and hinder granuloma formation, while suppression of RBX1 expression can decrease the degradation of inflammation-related proteins, thereby preventing the immune evasion of Mtb. ELAVL1, as a pro-inflammatory factor, exhibits anti-infective properties and holds potential therapeutic value. Furthermore, the enhancement of MRPL33 expression may mitigate the toxic side effects of antibiotics and reduce drug resistance. In summary, these four genes are closely related to the progression of TB and may serve as potential targets for the development of host-directed therapies for the treatment of this disease.

Data availability

The original gene expression profiles (GSE112104, GSE108731) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). All data generated or analysed during this study are included in its supplementary information files.

References

Organization, W. H. Global tuberculosis report 2023 (2023). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851

Furin, J., Cox, H. & Pai, M. Tuberculosis. Lancet, 393(10181): 1642–1656. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30308-3 (2019).

Mirzayev, F. et al. World Health Organization recommendations on the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2020 update. Eur. Respir J. 57 (6). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.03300-2020 (2021).

Bahuguna, A., Rawat, S. & Rawat, D. S. QcrB in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: the new drug target of antitubercular agents. Med. Res. Rev. 41 (4), 2565–2581. https://doi.org/10.1002/med.21779 (2021).

Dheda, K. et al. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, diagnosis, and management of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and incurable tuberculosis. Lancet Respir Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(17)30079-6 (2017).

Dookie, N. et al. The changing paradigm of drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment: successes, pitfalls, and future perspectives. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 35 (4). https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00180-19 (2022). e0018019.

Domínguez, Á. et al. Transcriptomics as a tool to discover new antibacterial targets. Biotechnol. Lett. 39 (6), 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-017-2319-0 (2017).

van Rensburg, I. C. & Loxton, A. G. Transcriptomics: the key to biomarker discovery during tuberculosis? Biomark. Med. 9 (5), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm.15.16 (2015).

Putim, C. et al. Secretome profile analysis of multidrug-resistant, monodrug-resistant and drug-susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch. Microbiol. 200 (2), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-017-1448-0 (2018).

Kaforou, M. et al. Transcriptomics for child and adolescent tuberculosis. Immunol. Rev. 309 (1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.13116 (2022).

Popov, D., Jain, L., Alhilali, M., Dalbeth, N. & Poulsen, R. C. Monosodium urate crystals alter the circadian clock in macrophages leading to loss of NLRP3 inflammasome repression: implications for timing of the gout flare. Faseb J. 37 (6). https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202202035R (2023). e22940.

Campaniço, A., Moreira, R. & Lopes, F. Drug discovery in tuberculosis. New drug targets and antimycobacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 150, 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.020 (2018).

Krug, S., Parveen, S. & Bishai, W. R. Host-directed therapies: modulating inflammation to treat tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 12, 660916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.660916 (2021).

Udinia, S., Suar, M., Kumar, D. Host-directed therapy against tuberculosis: concept and recent developments. J. Biosci. 48, 54 (2023).

Matos, P. et al. Small GTPase Rac1: structure, localization, and expression of the human gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 277 (3), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2000.3743 (2000).

Lodde, G. C. et al. Characterisation and outcome of RAC1 mutated melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 183, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2023.01.009 (2023).

Alaridah, N. et al. Mycobacteria manipulate G-Protein-coupled receptors to increase mucosal Rac1 expression in the lungs. J. Innate Immun. 9 (3), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1159/000453454 (2017).

Redelman-Sidi, G., Iyer, G., Solit, D. B. & Glickman, M. S. Oncogenic activation of Pak1-dependent pathway of macropinocytosis determines BCG entry into bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 73 (3), 1156–1167. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-12-1882 (2013).

Takada, Y., Ye, X. & Simon, S. The integrins. Genome Biol. 8 (5), 215. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215 (2007).

Wu, Y. et al. Mycobacterial infection is promoted by neutral sphingomyelinase 2 regulating a signaling cascade leading to activation of β1-Integrin. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 51 (4), 1815–1829. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495683 (2018).

Borza, C. M. et al. The collagen receptor discoidin domain receptor 1b enhances integrin β1-mediated cell migration by interacting with talin and promoting Rac1 activation. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 836797. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.836797 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nucleoside diphosphate kinase inactivates small GTPases leading to evasion of innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 9 (7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003499 (2013). e1003499.

Sarvari, P. et al. The E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Rbx1 regulates cardiac wall morphogenesis in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 480, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2021.07.019 (2021).

Migita, K. et al. Prognostic impact of RING box protein-1 (RBX1) expression in gastric cancer. Gastr. Cancer. 17 (4), 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0318-y (2014).

Awuh, J. A. et al. Keap1 regulates inflammatory signaling in Mycobacterium avium-infected human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112 (31), E4272–E4280. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1423449112 (2015).

Mena, E. L. et al. ORF10-Cullin-2-ZYG11B complex is not required for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (17). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023157118 (2021).

Mukherjee, R. & Dikic, I. Regulation of host-pathogen interactions via the ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 76, 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-041020-025803 (2022).

Atasoy, U., Watson, J., Patel, D. & Keene, J. D. ELAV protein HuA (HuR) can redistribute between nucleus and cytoplasm and is upregulated during serum stimulation and T cell activation. J. Cell. Sci. 111 (Pt 21), 3145–3156. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.111.21.3145 (1998).

Wang, J. G. et al. LFA-1-dependent HuR nuclear export and cytokine mRNA stabilization in T cell activation. J. Immunol. 176 (4), 2105–2113. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2105 (2006).

Papadaki, O. et al. Control of thymic T cell maturation, deletion and egress by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J. Immunol. 182 (11), 6779–6788. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0900377 (2009).

Zhou, Y., Chen, L. & Ni, S. Identification and functional characterization of zebrafish ELAVL1b as a new member of antimicrobial protein. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 135, 108671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108671 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. MRPL33 and its splicing regulator hnRNPK are required for mitochondria function and implicated in tumor progression. Oncogene 37 (1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2017.314 (2018).

Almeida, L. et al. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics impair T cell effector function and ameliorate autoimmunity by blocking mitochondrial protein synthesis. Immunity 54 (1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.11.001 (2021).

Pearce, E. L. & Pearce, E. J. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity 38 (4), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005 (2013).

Hamouche, L., Poljak, L. & Carpousis, A. J. Ribosomal RNA degradation induced by the bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor rifampicin. Rna 27 (8), 946–958. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.078776.121 (2021).

Hemeda, L. R. et al. Discovery of pyrimidine-tethered benzothiazole derivatives as novel anti-tubercular agents towards multi- and extensively drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 38 (1), 2250575. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2023.2250575 (2023).

Aouam, K. et al. Adverse effects of antitubercular drugs: epidemiology, mechanisms, and patient management. Med. Mal Infect. 37 (5), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2006.12.006 (2007).

Rankine-Wilson, L. I., Shapira, T., Emani, C. S. & Av-Gay, Y. From infection niche to therapeutic target: the intracellular lifestyle of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. (Reading). 167 (4). https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001041 (2021).

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Shenzhen Basic Research Special Projects (Natural Science Foundation) (No.JCYJ20220530163212027), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 32394014 and 32260883) and Shenzhen Science and Technology Project (No.JCYJ20230807153604010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZC: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. QW: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. QM, JC, XK, YZ, LL: Writing - review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. XW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Wang, Q., Ma, Q. et al. Identification of core biomarkers for tuberculosis progression through bioinformatics analysis and in vitro research. Sci Rep 15, 3137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86951-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86951-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring T-cell metabolism in tuberculosis: development of a diagnostic model using metabolic genes

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)