Abstract

In this paper, a Total Loss Minimization (TLM) modulation strategy is proposed to enhance the conversion performance of the series-resonant dual-active-bridge DC–DC converters. Unlike conventional modulations, this optimal approach targets the reduction of reactive power and circulating current, which are recognized as major contributors to conduction loss. Additionally, it addresses the switching loss, which typically results from hard-switching operations. The proposed total loss minimization modulation are select triple phase-shift control and switching frequency as the focal point of investigation to minimize the reactive power and circulating current, and maintain soft-switching operation. The effectiveness of the TLM modulation is analyzed under both buck and boost modes, showcasing its versatility. A comprehensive validation has been successfully conducted through experimental testing on a 300W laboratory prototype converter. The enhancement in conversion efficiency, a key innovative outcome of this research, is further confirmed by a comparative analysis with existing literature, underscoring the advancement in technology that this study presents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To meet the demands of societal consensus, the architecture of power generation has gradually shifted from conventional sources to renewable ones. Power electronics systems also evolve from the conventional way toward smart and sustainable way to make this paradigm of energy generation shift possible1. Among modern power electronics systems, the high-frequency(HF) isolated dc–dc converter (IDC) has received wide attention and has been widely implemented in different applications. The dual-active-bridge (DAB) dc–dc converter is a typical topology of IDC, which is characterized by bidirectional power flow, soft-switching capability, low control complexity and high conversion efficiency2. However, with traditional modulation, a DAB converter would suffer from switching and conduction loss. Several topologies modifications of the DAB converter have been proposed to eliminate the voltage ripple, reduce the circulating current and extend soft-switching region. The series-resonant dual-active-bridge (SRDAB) dc–dc converter is a resonant variant of the DAB converter which is formed by simply replacing the ac-link inductor of DAB converter with a series LC type resonant tank. The similarity in topology means that it may retain most of favorable features of DAB converter, including soft-switching capability, high power density, high efficiency and simple control. Also, the advantages offered by series-resonant tank include immunization to transformer saturation, nearly sinusoidal waveform and more flexibility of control. The phase-shifted modulation (PSM) is proposed to be controlled SRDAB converter solely on an outer phase-shift between primary and secondary inverter voltages for power regulation3. With possible arrangements of the outer phase-shifted, the SRDAB converter is able to achieve zero voltage switching (ZVS) for all switches in a wide range of load levels, which makes it suitable for photovoltaic application with medium to high output voltage. Small-signal model of a SRDAB converter is also developed for dynamic control based on the steady-state analysis of main power modes4. However, with conventional PSM or single phase-shift (SPS) control, SRDAB converter would face substantial conduction and switching loss problems, which arises from hard-switching operation, reactive power and circulating current respectively. To overcome conventional PSM apparently drawbacks, advanced phase-shifted modulation includes extended phase-shift (EPS) control5, dual-phase-shift (DPS) control6 and triple-phase-shift (TPS) control7 are investigated step by step. These advanced modulations are utilized the one or more internal phase-shifts, which is the inherent features of the SRDAB converter topology. However, the converter under EPS or DPS control still suffers from extra switching loss since the soft-switching operation can not maintained for secondary side switches at light load condition. With fundamental harmonics approximation (FHA) approach, the practical steady state of TPS control is analyzed to extend soft-switching range, but the resonant current is affected by higher order harmonics due to the limitations in fundamental component analysis.

Some modified resonant immittance network for DAB converters featuring switched-impedance-based tank were introduced in8,9. These topologies aim to minimize conduction losses by maintaining a unity power factor, thereby reducing reactive power. However, the ZVS operation is lose in most of the operating region, especially when far from the unity voltage gain. A resonant network topology with a y-type CLLC tank was discussed to ensure soft switching operation over whole load range, but it also results in a massive circulating current at lower load levels10. A interleaved connection resonant network was based on the LCLL tank was proposed to mitigate driving loss11, and a CLCLC type fifth-order resonant DAB converter was investigated to extend soft-switching region12. However, the pursuit of these high-order topologies improvements often involves increased in both control and computational complexity.

In the relevant literature, numerous optimized modulation have been proposed to overcome the aforementioned drawbacks, with most focusing on extending the range of soft-switching operation. Although the switching performance has been significantly enhanced, these optimizations cannot achieve optimal operating conditions for the converter which leads to a low power factor, high current stress, and substantial reactive power. Thus, The reactive power optimal control has gained considerable attention in recent year. The LLC type resonant DAB converter with discontinuous current modulation was proposed for hold-up applications to reduced reactive power13. But this method unable to maintain the whole range ZVS operation when the converter gain is varying. To eliminate circulating current, a boundary current modulation is proposed14. However, this modulation is inapplicable at the light load condition since a huge leakage inductance that reflected to the secondary side leads to the hard-switching operation. An advanced modulation based on the minimum current trajectory was proposed to minimize resonant current, but this method has low power factor at light load conditions15. A TPS-based optimal modulation for DAB converter is proposed, with the objective function defined by the reactive power expression. This strategy significantly enhances the converter efficiency under light load conditions and over a wide gain range.

In addition to PSM, Frequency Modulation (FM) can also be utilized for a SRDAB converter to achieve soft-switching operation across the entire load range16. However, this approach necessitates a significant variation in the switching frequency, which may be impractical for implementation. A complex frequency modulation scheme was proposed17, which not only ensures ZVS operation across the full range but also eliminates circulating current. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of this modulation under light load conditions has not been verified, and the output voltage may fail to track the reference value amidst substantial load variations. A comprehensive frequency-domain analysis of the conventional PSM was conducted18, suggesting an optimal design procedure for the SRDAB converter. Yet, this method does not guarantee ZVS across the entire range, and achieving minimum resonant current operation remains a challenge. To harness the advantages of both PSM and FM, a multi-mode control strategy with diverse control paths has been proposed, leveraging artificial intelligence-based methods19,20,21,22. While these methods can significantly enhance converter efficiency, they also present a notable drawback: the absence of straightforward analytical solutions.

According to the review, the reported solutions are either too complicated or exhibit weak performance under light load conditions. This work focuses on Total Loss Minimization (TLM) modulation for a series-resonant dual-active-bridge DC–DC converter. The primary objectives of TLM modulation are to minimize reactive power, eliminate circulating current, and ensure soft-switching operation across a broad range of loads and converter gains. The main contributions of this work include: (1) An optimal modulation strategy with minimum reactive power, zero circulating current, and soft-switching features is proposed, which reduces both conduction loss and switching loss over a wide range of load and converter gains. (2) Although the proposed modulation is a multi-dimensional approach, it can be simplified, making the calculation of control parameters straightforward. (3) The typical steady-state operation of an SRDAB converter with TPS and FM is analyzed, providing guidance for the selection of specific control strategies. These contributions significantly lower economic costs and design complexity, leading to high-efficiency performance in a cost-efficient manner.

The paper is organized as follows: First, a steady-state analysis of TPS control using the FHA approach is conducted to reveal the control features. Then, under the proposed TLM modulation, minimum reactive power operation with zero circulating current is achieved, resulting in minimized reactive-power-induced conduction loss. Furthermore, switch behavior is evaluated through a comprehensive consideration of the dead-band interval, and the range of switching frequency is determined using an adaptable method. The detailed design procedure customized for TLM modulation is explained in Section “Total loss minimization modulation”. Verification based on a 300W prototype converter, extensive experimental tests are presented, along with a comparison with previous related works, including both simulation and experimental results. Finally, conclusions and contributions are summarized in the final section.

Operation of SRDAB converter with TPS control

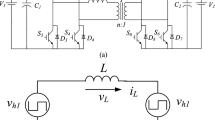

The schematic diagram of a SRDAB converter is depicted in Fig. 1. The primary side and secondary side inverter adopts two full bridge topology with eight active switches \(S_1 - S_8\). \(D_{S1} - D_{S8}\) are eight parasitic diodes of each switches. \(C_{S1} - C_{S8}\) are eight junction capacitors or snubber. Those parasitic diodes and junction capacitors are parallel connected with active switches. \(V_{in}\) is a DC source. \(C_{in}\) and \(C_{out}\) are high frequency filter capacitors. The series resonant tank includes an resonance inductor \(L_r\) and a resonance capacitor \(C_r\) which is connected to the primary side as the main energy transfer device. \(i_{r}\) and \(V_r\) are resonant current and resonant voltage across the resonant tank. \(r_k\) is the sum value of the equivalent resistance of \(L_k\) and the winding resistance of the HF transformer. \(v_{p}\) and \(v_{s}\) are HF output voltages on the primary and the secondary side, respectively. The turn ratio of HF transformer is defined as \(n_t: 1\). The voltage gain of the SRDAB converter is defined as \(G = n_tV_{out} / V_{in}\).

Two switches in one bridge leg are controlled complementarly with a 50% duty cycle and necessary dead band time. The fixed switching frequency \(f_s\) with high frequency period is \(T=\pi\). The SRDAB converter is regulated in TPS control with three independent phase-shifts for power delivery. An outer phase-shift \(\varphi\) exists between the gating signal of \(S_1\) and \(S_5\). And, two independent interval bridge phase-shift \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) are defined as the turn on moment of \(S_1\) and \(S_5\) leads that of \(S_4\) and \(S_8\). In this work, all the optimization were performed in the forward power mode(power flowing from \(V_{in}\) to \(V_{out}\)). And, the reverse power mode(power flowing from \(V_{out}\) to \(V_{in})\) can be concluded as similar method as forward power mode. The range of phase-shift are \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\), \(\varphi \in [0,\pi ]\). Hence, both \(v_{p}\) and \(v_{s}\) are became a quasi-square wave HF voltage where the pulse width of \(v_p\) corresponds to \(\delta _1\) and that of \(v_s\) corresponds to \(\delta _2\). Before detail performing the operation analysis, all assumptions regarding the switches, diodes, inductors, capacitors, and transformers are ideal.

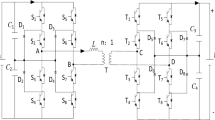

In Fig. 2, the typical TPS control mode of SRDAB converter is presented, which has gained considerable attention due to soft-switching capability and conversion efficiency performance. This mode comprises ten distinctive time intervals in a HF switching period where the \(v_p\), \(v_s\) and \(i_r\) of each time interval are different. Before a new HF period, the \(v_{p}\), \(v_{s}\) and \(i_{r}\) are assumed to be negative. Then, the equivalent circuits with current flowing path of first five interval are shown as Fig. 3.

Interval 1 [\(0\sim t_1\)] (as Fig. 3a): After \(S_2\) turn-off instant, the body diode \(d_1\) begin to conduct naturally since \(i_r\) is negative. Hence, \(S_1\) can turn-on with zero voltage once gating signal is applied. The primary side voltage \(v_p\) changes to zero as both \(S_1\) and \(S_3\) are conducting. The current path in the secondary side flows through from \(S_7\) to \(S_6\) so that \(v_s\) remains at \(V_{out}\).

Interval 2 [\(t_1\sim t_2\)] (as Fig. 3b):The gating signal of \(S_4\) is applied at the initial of second interval. The negative \(i_r\) is instinctively tended to flow through \(d_4\) which ensure zero voltage turn-on of \(S_4\). With conduction between \(S_1\) and \(S_4\), \(v_p\) is clamped to \(V_{in}\), and the secondary side current flow remains unchanged. Interval 2 ends when \(i_r\) reaches zero.

Interval 3 [\(t_2\sim t_3\)] (as Fig. 3c): This interval starts with the resonant current turns to zero. The \(i_r\) changes its polarity from negative to positive, where the conduction route of both side are no change.

Interval 4 [\(t_3\sim t_4\)] (as Fig. 3d): This interval begins with \(S_5\) turn-on instant. The \(S_5\) is turn-on with ZVS operation due to the similarly \(i_r\) flowing path. The secondary inverter voltage \(v_s\) commutates to zero as both \(S_5\) and \(S_7\) are conducting. Electric energy is stored in the resonant tank during this interval.

Interval 5 [\(t_4\sim \pi\)] (as Fig. 3e): The fifth interval starts when \(S_7\) gating signal is removed. \(S_8\) can be turn-on with soft-switching easily. The primary inverter voltage \(v_p\) maintains in \(V_{in}\). The electric energy is delivered to load via the secondary side through \(S_5\) and \(S_8\), which the secondary side voltage \(v_s\) clamps to \(V_{out}\).

The subsequent five intervals (from \(\pi\) to \(2\pi\)) are symmetric to the first five intervals with reversed polarities of \(v_{p}\), \(v_{s}\) and \(i_{r}\), which can be easily obtained by regarding to Fig. 2.

Steady state analysis

In the following steady state analysis, normalized variables are used so that generalized results are obtained and applicable to all power levels. All quantities would be normalized by the following base values as shown in (1).

where \(R_F\) is the full-load output resistance and \(\omega _r\) is the resonant frequency. Hence, the normalized voltage phasor expressions are obtained as (2) and (3).

where \(\omega _s\) is switching angular frequency. The per-unit impedance of the resonance tank is given as (4).

Where the normalized resonant tank impedance K and F are given as \(F=\frac{\omega _s}{\omega _r}\), \(K=\frac{\omega _rL_r}{R_L}\).

Assuming that higher order voltage and current harmonics components are blocked by resonant tank, FHA approach is applied with acceptable accuracy.

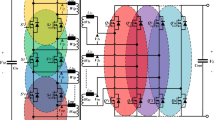

The time domain equivalent circuit of SRDAB converter with fundamental harmonics components is presented as Fig. 4. The normalized inverter voltages \(v_p\) and \(v_s\) in first terms of fourier series are given as (5) and (6).

To obtain the complex power with phasor, the fundamental components of \(v_p\) and \(v_s\) are represented in phasor from as \(\varvec{U_p}\) and \(\varvec{U_s}\) which can be rewritten as (7) and (8).

Then the resonant current \(i_r\) can be presented in phasor from \(\varvec{I_{r}}\) as (9).

Regarding to (7) and (9), the complex power in primary HF inverter can be obtain as (10).

The the normalized active power \(P_{pu}\) and reactive power \(Q_{pu}\) can be expressed as (11) and (12).

Referring to the (9) and (11), the rms resonant current \(I_{r,rms}\) can be solved as (13).

The resonant tank capacitance rms voltage can be given as (14).

With (11), the converter gain can represented as (15).

Where \(P_{pu}=G^2L_d\). And, \(L_d\) is Load level, which \(L_d\in (0,1]\).

Total loss minimization modulation

With the aforementioned steady state analysis, the total loss minimization (TLM) modulation is proposed which is expected to realize three objectives: minimum reactive power, zero circulating current, and soft-switching operation.

Reactive power minimization

The first objective of TLM modulation is to minimize the reactive power for conversion efficiency improvement. The relationship of the reactive power with the \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) and converter gain G with fixed \(\varphi\) is shown in Fig. 5, which considers both buck mode (\(G<1\)) and boost mode (\(G>1\)). It illustrates that a large inner bridge phase-shift \(\delta _2\) and converter gain G will lead to an increase in reactive power. As \(\delta _1\) varies, a higher G causes a higher initial reactive power, indicating that reactive power exhibits a negative correlation with \(\delta _1\). Therefore, the reactive power can reach minimum value by appropriate \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) and G combination.

To minimize reactive power with required active power, the Lagrangian multiplier method is adopted to solve minimum relationship of \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) and \(\varphi\). The Lagrangian multiplier method is defined as (16).

where \(\lambda\) is Lagrangian multiplier constraint and \(P^*_{pu}\) is a specified power level. Mathematically, the expected minimum solution of \(Q_{pu}\) demands to solve the first partial derivatives of \(\varvec{L}_{\delta _1,\delta _2,\varphi }\) to zero, with respect to \(\delta _1,\delta _2,\varphi\), respectively. Thus, the required conditions of Lagrangian multiplier method can be given as (17).

By solving (17), the relationship of minimum solution of \(Q_{pu}\) are obtained as (18).

With complication of (18), there are two groups of possible solutions available. The required conditions for minimum \(Q_{pu}\) are presented as (19)for buck mode (\(G\leqslant 1\)) and (20) for boost mode (\(G>1\)).

Circulating current minimization

High conduction loss always arises from circulating current. In the light blue region of Fig. 2, the resonant current \(i_{r}\) has an opposite polarity with \(v_{p}\), which results in a low power factor. The low power factor leads to substantial circulating current. Consequently, the conduction loss in the winding resistance of components are considerable. To improve the conversion efficiency, the circulating current should be minimized and soft-switching operation should be maintained.

To completely operate without the circulating current, the turn-on instant of \(S_4\) and \(S_5\) should be aligned with zero-crossing point of resonant current \(i_r\), which can be described as (21) and (22).

Referring to the (21), the (22) can be reformatted as (23).

By substituting (23) into (19) and (20), two solutions can be found for buck and boost operation respectively through careful analysis.

The first solution is valid for the buck mode only (\(G\leqslant 1\)), which is shown as (24).

The second solution is for applicable for the boost mode (\(G>1\)), which is shown as (25).

Then, the TLM modulation waveform of SRDAB converter with minimum reactive power and circulating current are given as Fig. 6.

For a better explanation of this optimization, the fundamental phasor diagrams of the two optimal solutions are given in Fig. 7. In any case of phasor, \({\varvec{U_p}}\) leads the transformer voltage \({\varvec{U_s}}\) by \(\varphi\) as illustrated in Fig. 6. Due to zero circulating current, the resonant current phasor is always perpendicular to the phasor \(V_{Cr}\). Hence, the current phasor should be aligned with either of the adjacent voltage phasors \({\varvec{U_p}}\) or \({\varvec{U_s}}\).

With minimized reactive power, the phasor form becomes a right-angle triangle for both solutions as shown in Fig. 7. When \(G<1\), the minimum reactive power \({\varvec{I_r}}\) is in phase with \({\varvec{U_s}}\). Due to \(\varphi =0\), the magnitude of \({\varvec{U_s}}\) reaches its maximum which is perpendicular with \(V_{Cr}\). When \(G>1\), the minimum reactive power \({\varvec{I_r}}\) is in phase with \({\varvec{U_p}}\), which indicates the phase angle of \({\varvec{I_r}}\) is zero, i.e. \(\delta _1=\pi\). Consequently the magnitude of \({\varvec{U_p}}\) is its maximum. The phasor diagram will always be a right-angle triangle regardless of load level or gain. When the gain is fixed, the shape of the phasor triangle does not change under any condition. When the gain changes, a new right-angle triangle with different angles is formed.

A simulated comparison among the proposed TLM modulation and conventional phase-shift modulations with varying normalized reactive power and normalized active power is shown in Fig. 8. As active power level grows, the reactive power indicates growth trend. Furthermore, the phase-shift control with inner bridge phase-shift \(\delta _1\) or \(\delta _2\) would result in a lower reactive power. Thus, the proposed modulation has apparent lower reactive power than other conventional PSM under all load regions.

Switching behavior evaluation

It can be concluded from operation analysis (as Fig. 3 and describe in Section “Operation of SRDAB converter with TPS control”) that to ensure soft-switching operation in the primary side inverter, \(i_r\) should be negative at the turn-on instances of S1 and S4. As for secondary side, it can be deduced that \(i_r\) should be positive at the turn-on instances \(S_8\) and negative for that of \(S_7\). The \(i_r\) can be evaluated when \(\omega _st=(0, \pi -\delta _1)\) at the buck mode and \(\omega _st=(0,\varphi )\) at the boost mode. So that the soft-switching necessary condition for the converter with TLM modulation can be concluded as (26) for \(G\leqslant 1\) and (27) for \(G>1\).

However, Eqs. (26) and (27) are not a sufficient condition for soft-switching operation. It is necessary to provide sufficient tank current and dead-band interval to charge/discharge the parasitic capacitances of the switches in same switch leg, which is displayed as Fig. 9. The required soft-switching operation to charge/discharge parasitic capacitances are list at (28).

Where \(Q_{C,max}=\int _{0}^{v}2C_{max}(v)dv=2vC_{max}(v)\) which is the required maximum charge for the parasitic capacitances of two complementary switches in the both side. \(Q_{C,max}\) are determined by the total switch output capacitance and the switch voltage. Assuming that \(T_p\) and \(T_s\) are the effective minimum dead-band phase-shift required for the switches to achieve complete soft-switching transitions. To maintain soft-switching on both side, the resonant current is expected to remain at zero when \(S_4\) turn-on and \(S_6\) turn-off. Hence, for both \(T_p\) and \(T_s\) has long enough duration to charge/discharge parasitic capacitances. However, if the dead-band is larger than the necessary value, the reactive power becomes large.

Based on (28), an appropriate compensated \(T_p\) and \(T_s\) can be selected to ensure the ZVS for all the switches in a wide power range. Meanwhile, an appropriated dead band should be added to prevent the occurrence of short circuit.

Range of switching frequency

By combining the required conditions for reactive power minimization, circulating current minimization and soft-switching operation, the \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) and \(\varphi\) cannot be varied arbitrarily. By changing \(X_{pu}\) according to (11), the effects on active and reactive power are observed when G, \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\), and \(\varphi\) are fixed. Varying the switching frequency changes the resonant frequency \(f_r\), allowing the converter load level to be regulated. Thus, switching frequency modulation can overcome the limitation, as it allows \(f_s\) to become a control variable.

With (11) and (12), the variation of converter gain G respect to \(X_{pu}\) with different \(P_{pu}\) and \(Q_{pu}\) is given as Fig. 10. It is seen from Fig. 10a that increasing the \(X_{pu}\) will reduce the load level when the converter gain G is fixed. Besides, as shown in Fig. 10b, \(Q_{pu}\) has minimal impact on \(X_{pu}\) due to optimization limitations on variables. Hence, the \(P_{pu}\) dominates the value of \(X_{pu}\).

According to (11) and (12), the SRDAB converter cannot be regulated with \(G=0\) which cannot provide the sufficient condition of soft-switching operation. By analyzing (28), the most appropriate dead-band intervals \(T_p\) and \(T_s\) to ensure the soft-switching operation is determined. However, the parasitic capacitances of switches are unable to be completely discharged with the appropriate dead-band interval when \(P_{pu}\) is below 0.3. Hence, the \(P_{pu}\) is limited between 0.25 and 1. At the minimum \(P_{pu}\), the converter is supposed to fix phase-shift and change switching frequency. According to (11), the switching frequency F can be calculated as (29).

where the constant \(N = \frac{{\sin \frac{{\delta _{1} }}{2}\sin \frac{{\delta _{2} }}{2}\sin \left( {\varphi + \frac{{\delta _{2} }}{2} - \frac{{\delta _{1} }}{2}} \right)}}{{2GK}}\).

Implementation might be impractical with a wide range of switching frequency variations. It is assumed in frequency design that the maximum switching frequency \(F_{max}\) is limited to twice of the normalized switching frequency, and \(F_{max}\) occurs at light load of minimum voltage gain \(G_{min}\).

Thus, the normalized switching frequency F is solved to be 1.21, and the rated power quality factor K is set to 1.43.

Design procedure and experimental results

To validate the theoretical analysis above, the specifications for the prototype are designed. The detailed specifications of the prototype converter are listed at Table 1. The converter has a rated power \(P_{rated} =300\) W with a fixed switching frequency at \(f_s=50\) kHz. The input voltage \(V_{in}\) changes from 90 V to 120 V with a unity gain at a rated input voltage of 100 V, an output voltage \(V_{out}\) is fixed at 100 V. Turn ratio of transformer is \(n_t=5:6\). Then, with \(F = 1.21\) and \(K = 1.43\), the resonant tank specifications \(L_r\) and \(C_r\) are calculated as (31).

Using the specifications provided in Table 1, simulation experiments were conducted in MATLAB Simulink, where TLM modulation was comparatively verified. Figure 11 shows the reactive power under different control schemes at the same output power level \(P_o=300\) W. The comparison results of Figs. 8 and 11 indicate that TLM modulation has the lowest reactive power among all control schemes. Therefore, the TLM modulation proves that it can effectively reduce the reactive power both theoretically and in simulation.

A lab prototype of a SRDAB converter was built and tested for validation of the proposed TLM modulation as well. The Experimental prototype converter layout is setup as Fig. 12 shown. All the switches on H-Bridge are implemented with IPP320N20N (200V, 34A, \(R_{ds}\)=32 \(m\Omega\), \(Q_{C,max} =55\) nC at \(V_{ds}=250\) V) from Infineon. The dead-band \(T_p\) and \(T_s\) are determined with detail \(Q_{C,max} =55\) nC. An EA 8360-15T bench power supply is used as the input DC source, and the load is a BK 8510 programmable DC electronic load. The HF transformer is made from an ETD49 ferrite core with a material type of N97. The actual turn ratio of windings is 20:24 (\(n_t=5:6\)) and the resulted magnetizing inductance is 4 mH. An EP4CE115F23I7N FPGA board from Altera is applied as the PWM generator to generate the gating signals of converter. The detail implementations of prototype are listed in Table 2.

The closed-loop control realization of the proposed TLM modulation is shown in Fig. 13. The secondary side voltage \(V_{out}\) is stabilized by a proportional-integral (PI) compensator. The switching frequency \(f_s\) are determined by PI regulator from feedback loop, balancing input and output power of converter. Then, the voltages \(V_{in}\) and \(V_{out}\) are sampled online to calculate the converter gain G. This gain is fed to a PWM generator which generates appropriate gating signals for SRDAB converter.

The prototype converter is tested under TLM modulation for buck mode at input voltage \(V_{in}\)=110V (correspond to \(G=0.9\)) and boost mode \(V_{in}\)=90V (correspond to \(G=1.1\)) in which total of 28 operating points have been validated. For both buck mode and boost mode, the full load condition (\(P_{pu}\) = 300 W) and light load condition (\(P_{pu}\) = 100 W) are depicted in Fig. 14, which recording primary side voltage \(v_p\), secondary side voltage \(v_s\), resonant tank voltage \(V_{cr}\) and resonant current \(i_r\) in each plot. All waveform of each load conditions match the predicted ones as Fig. 6. For the buck mode, the phase-shifts is \(\delta _1 = 144.9^\circ\), \(\delta _2=180^\circ\) and \(\varphi =0^\circ\). For the boost mode, the phase-shifts is \(\delta _1 = 180^\circ\), \(\delta _2=143.3^\circ\) and \(\varphi =36.7^\circ\). Varying frequency method is adopted for power regulation. So that, in same converter gain, the different load levels has similar waveform since it shares the phase-shifts \(\delta _1\), \(\delta _2\) and \(\varphi\). The deference is that the case of full load condition use a rated switching frequency of \(f_s=50\) kHz, and the light load obtains with a higher switching frequency \(f_s = 70.8\) kHz for buck mode and \(f_s = 63.5\) kHz for boost mode.Although, a small deviations exists at light load due to high order harmonics, the theoretical results and experimental results can be identified from the data for most of cases. Therefore, with TLM modulation, the reactive power is minimized and the circulating current is eliminated successfully.

As Fig. 15 illustrates the details of the behavior associated with the switches for buck mode and boost mode at light load conditions. ZVS operation of each switch is observed by comparing its gate-source voltage and drain-source voltage together. As predicted, all the switches are operates in under TLM modulation with sufficient margin. Due to waveform consistency for a fixed input voltage, the switching behavior with different load level are similar, therefore all switches have realized soft-switching operation in all design voltage gain range.

The comparative analysis of key parameters across various output power levels is systematically presented in Tables 3 and 4, corresponding to input voltages of \(V_{in}=110\) V and \(V_{in}=90\) V, respectively. A close correlation between the calculated and measured values is discernible from the data in the majority of the cases.

The transient experimental result for the load step response is evaluated too. To setup a feedback loop, a simple PI controller is applied with \(K_p=2.29\) and \(K_i=66\). The load step response is presented at Fig. 16 with load step changed from 150 W \(\rightarrow\) 200W \(\rightarrow\) 150 W. It can be seen that there is no obvious current and voltage overshoot. The transient performance demonstrates the stability of the proposed modulation in the converter.

An efficiency comparison between the proposed modulation and other two previous related modulations are given in Fig. 17a and b. It is seen that the efficiency of proposed modulation (square marks) outperforms the other two modulations. This maximum efficiency reaches 95.2% which is achieved at full load conditions of buck mode, and even at light load the efficiency is kept over 92% in the experimental test. Thus, The efficiency result also shows that TLM modulation is the most effective method for the light-load condition. Figure 17c and d show the reactive power in both buck mode and boost mode. It can be seen that the measured reactive power with all these control methods is increasing along with the load level, while the proposed modulation has the lowest reactive power across the entire range. The proposed modulation indeed provides more efficient since the ZVS operation are maintained, and reactive power and circulating current are minimized. It can be concluded that both the reactive power and the conversion efficiency under the proposed modulation are improved and the overall improvement is valid for a variation of converter gain.

The total loss breakdown of the proposed TLM modulation is illustrated in Fig. 18 in which \(V_{in} = 110\) V is selected as an example. For simplicity, the general expression for calculating the total loss can be given as follows (32):

where \(P_{cond}\), \(P_{sw}\), and \(P_{core}\) are the conduction loss, switching loss, and core loss, respectively.

To perform loss analysis and modeling of the proposed converter, the conduction loss is calculated using (33):

where \(R_X, R_T, R_{on,p}\), and \(R_{on,s}\) are the parasitic resistances of the resonant tank \(X_{pu}\), HF transformer winding, and primary-/secondary-side MOSFETs, respectively. The phasor from of \(I_r\) is provided by (13).

With switching behavior, it can be concluded that the switching losses of \(S_1, S_2, S_5, and S_6\) are negligible due to soft-switching operation. Thus, the switching loss is only considered for \(S_3\) or \(S_4\) in the soft-switching boundary cases, for which the switching loss is obtained as follows (34):

where \(T_r\) and \(T_f\) are the respective rise and fall times of the current and voltage of the MOSFETs on both sides. As Fig. 9 shows, the sufficient conditions (boundary case) of ZVS operation with our proposed strategy are \(T_r = T_f = T_{DB}\).

The core loss is usually related to the materials, and is provided by (35):

where \(K_f\) is the basic loss coefficient, \(A_{lm}\) is the volume, b is the magnetic core loss exponent, and \(\Delta B_T\) and \(\Delta B_X\) are the respective magnetic flux densities of the HF transformer magnetic core and resonant magnetic core with actual turns \(n_t\) and \(n_X\).

Thus, it is clearly seen from the Fig. 18 that the loss is mainly contributed by transformer loss over the whole load range. Admittedly, there may be some measurement errors on loss breakdown, but this does not adversely affect the conclusion that the converter works efficiently.

Conclusions

In the presented work, a series-resonant dual-active-bridge converter with the total loss minimization modulation is investigated comprehensively to achieve complete soft switching operation, minimum reactive power, and zero circulating current operation. Firstly, the typical steady state of the SRDAB converter is discussed in detail, including operating waveform, switching intervals, resonant current characteristics and power characteristics. The TPS control is selected as target scheme to minimize reactive power. On the basis of minimum reactive power, the zero circulating current operation under TLM modulation for both buck and boost mode are identified. The switching frequency is manipulated to control the output power. To verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed total loss minimization modulation, the simulation and experimental results are presented, comparing the proposed modulation with the conventional one. With a voltage feedback loop, the proposed topology and modulation is also demonstrated to have high control stability in experimental test. The conclusion can be drawn that the SRDAB converter with the proposed TLM modulation can effectively reduce the total losses and successfully enhances overall performance.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article. For further detail data analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

De Doncker, R. W., Divan, D. M. & Kheraluwala, M. H. A three-phase soft-switched high power density DC/DC converter for high power applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 27, 63–73 (1991).

Zhao, B. et al. Overview of dual-active-bridge isolated bidirectional dc–dc converter for high-frequency-link power conversion system. Trans. Power Electr. 8, 4091–4106 (2014).

Rathore, A. K. & Prasanna, U. R. Analysis, design, and experimental results of novel snubberless bidirectional naturally clamped ZCS/ZVS current-fed half-bridge DC/DC converter for fuel cell vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 60, 4482–4491 (2013).

Malan, W., Vilathgamuwa, D. M. & Walker, G. Modeling and control of a resonant dual active bridge with a tuned CLLC network. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 31(10), 7297–7310 (2016).

Zhao, B., Yu, Q. & Sun, W. Extended-phase-shift control of isolated bidirectional DC–DC converter for power distribution in microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27, 4667–4680 (2012).

Zhao, B., Song, Q. & Liu, W. Power characterization of Isolated bidirectional dual-active-bridge DC–DC converter with dual-phase-shift control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27, 4172–4176 (2012).

Wu, K., de Silva, C. W. & Dunford, W. G. Stability analysis of isolated bidirectional dual active full-bridge DC–DC converter with triple phase-shift control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27, 2007–2017 (2012).

Twiname, R. P., Thrimawithana, D. J., Madawala, U. K. & Baguley, C. A. A dual-active bridge topology with a tuned CLC network. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 30(12), 6543–6550 (2015).

Yaqoob, M., Loo, K. & Lai, Y. M. Fully soft-switched dual-active-bridge series-resonant converter with switched-impedance-based power control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(11), 9267–9281 (2018).

Chan, Y. P., Loo, K. H., Yaqoob, M. & Lai, Y. M. A structurally reconfigurable resonant dual-active-bridge converter and modulation method to achieve full-range soft-switching and enhanced light-load efficiency. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34(5), 4195–4207 (2019).

Muthuraj, S. S., Kanakesh, V. K., Das, P. & Panda, S. K. Triple phase shift control of an LLL tank based bidirectional dual active bridge converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32(10), 8035–8053 (2017).

Yaqoob, M., Loo, K., Chan, Y. P. & Jatskevich, J. Optimal modulation for a fifth-order dual-active-bridge resonant immittance dc–dc converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35(1), 70–82 (2020).

Chen, W., Rong, P. & Lu, Z. Snubberless bidirectional dc–dc converter with new CLLC resonant tank featuring minimized switching loss. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 57(9), 3075–3086 (2010).

Xu, G., Sha, D., Xu, Y. & Liao, X. Hybrid-bridge-based dab converter with voltage match control for wide voltage conversion gain application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(2), 1378–1388 (2018).

Corradini, L. et al. Minimum current operation of bidirectional dual-bridge series resonant DC/DC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27(7), 3266–3276 (2012).

Zhou, S., Li, X., Zhong, Z. & Zhan, X. Wide ZVS operation of a semi dual-bridge resonant converter under variable-frequency-phase-shift control. IET Power Electron. 33(8), 867–881 (2020).

Riedel, J., Holmes, D. G., McGrath, B. P. & Teixeira, C. ZVS soft switching boundaries for dual active bridge DC–DC converters using frequency domain analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32(4), 3166–3179 (2017).

Kundu, U., Pant, B., Sikder, S., Kumar, A. & Sensarma, P. Frequency domain analysis and optimal design of isolated bidirectional series resonant converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 54(1), 356–366 (2018).

Sha, D., Zhang, J. & Sun, T. Multi-mode control strategy for SiC MOSFETs based semi dual active bridge dc–dc converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34(6), 5476–5486 (2019).

Baldan, M., Di Barba, P. & Lowther, D. A. Physics-informed neural networks for inverse electromagnetic problems. IEEE Trans. Magn. 59(5), 1–5 (2023).

Li, X., Zhang, X., Lin, F., Sun, C. & Mao, K. Artificial-intelligence based triple phase shift modulation for dual active bridge converter with minimized current stress. IEEE. J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 11(4), 4430–4441 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Data-driven modeling with experimental augmentation for the modulation strategy of the dual-active-bridge converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 71(3), 2626–2637 (2024).

Funding

This research work were funded by “GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation No. 2022A1515111037” and “Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou No. 2023A04J2019”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Zhou did most of the theoretical analysis, derivation, circuit implementation, experimental testing and paper writing. J.Wang was responsible for simulation implementation, experimental testing and data proof reading. J.Tang was responsible for theoretical analysis, planning, coordination and proof reading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, S., Wang, J. & Tang, J. A total loss minimization modulation for series-resonant dual-active-bridge dc–dc converter with triple phase shift control. Sci Rep 15, 5932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86964-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86964-2