Abstract

Glyphosate (Gly) is a widely used herbicide for weed control in agriculture, but it can also adversely affect crops by impairing growth, reducing yield, and disrupting nutrient uptake, while inducing toxicity. Therefore, adopting integrated eco-friendly approaches and understanding the mechanisms of glyphosate tolerance in plants is crucial, as these areas remain underexplored. This study provides proteome insights into Si-mediated improvement of Gly-toxicity tolerance in Brassica napus. The proteome analysis identified a total of 4,407 proteins, of which 594 were differentially abundant, including 208 up-regulated and 386 down-regulated proteins. These proteins are associated with diverse biological processes in B. napus, including energy metabolism, antioxidant activity, signal transduction, photosynthesis, sulfur assimilation, cell wall functions, herbicide tolerance, and plant development. Protein-protein interactome analyses confirmed the involvement of six key proteins, including L-ascorbate peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, glutaredoxin-C2, peroxidase, glutathione peroxidase (GPX) 2, and peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase A3 which involved in antioxidant activity, sulfur assimilation, and herbicide tolerance, contributing to the resilience of B. napus against Gly toxicity. The proteomics insights into Si-mediated Gly-toxicity mitigation is an eco-friendly approach, and alteration of key molecular processes opens a new perspective of multi-omics-assisted B. napus breeding for enhancing herbicide resistant oilseed crop production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern agriculture, glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine) is a systemic non-selective herbicide valued for its broad-spectrum effectiveness against a diverse range of weeds. Since its introduction in the 1970s, Gly become an essential component of worldwide agricultural operations, especially with the rise of genetically engineered crops that are resistant to its effect1. This compatibility led to more effective weed control, reduced labor costs, and increased agricultural productivity and overall farming efficiency. Despite its widespread use and effectiveness, the indiscriminate application of Gly has raised concerns about its environmental and ecological impacts, particularly on non-target plant species2. Scientific research has linked the widespread use of Gly to potential negative impacts, including biodiversity loss, the emergence of Gly-resistant weed species, and disturbance to microbial communities in soil ecosystems3.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underpinning Gly tolerance in plants is critical in developing environmentally suitable approaches to reduce glyphosate-induced toxicity. Silicon (Si) has emerged as a promising agent for enhancing plant resistance against various abiotic and biotic stresses, counteracting the negative impacts of Gly on non-target plants4,5. Recent studies have revealed the significance of Si in modulating plant physiological responses, including those related to stress tolerance mechanisms through restoring redox homeostasis6. However, the molecular basis of Si-mediated mitigation of Gly toxicity, particularly in B. napus L., remain largely unexplored.

Brassica napus L., also commonly known as rapeseed or canola, is an economically significant oilseed crop that substantially contributes to the edible oil sector. It contains high levels of essential fatty acids, carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals and plays an important role in the human diet by providing a variety of nutritional advantages7,8. It also provides a sustainable source for biodiesel and biolubricant production. However, it has been observed to exhibit lower yield and modified physiological processes when exposed to Gly, highlighting the need for sustainable farming approaches that minimize these harmful effects9. Due to the distinct genetic makeup and the biochemical compositions, this plant is an ideal model for advanced study on the resilience mechanisms, especially when it comes to environmental stresses such as glyphosate-induced toxicity10,11. Hence, this work utilizes the resilient features of B. napus to uncover the underlying proteomic responses and adaptive mechanisms used by this plant to counteract the Gly-induced stress, integrating the physiological observations with state-of-the-art proteomic techniques.

The advent of proteomics has provided insights into the complex molecular dynamics of plant responses to various environmental stressors12. Label-free quantification is a widely used proteomic technique that enables comprehensive and unbiased assessment of protein expression changes without requiring complex labeling processes13. This contrasts with traditional gel-based approaches, which, while effective, are sometimes constrained by their lower throughput and sensitivity. Researchers may now unravel the intricate networks of protein interactions as well as modifications that help plants sustain herbicide-induced stress by exploiting the capabilities of label-free proteomics14.

Thus, our study aims to elucidate the protective implications of Si in B. napus exposed to Gly, using a label-free proteomic approach to map the protein expression landscape. We sought to understand the molecular mechanisms behind silicon’s mitigating effects by studying the differential expression of proteins involved in critical biological functions such as energy metabolism, photosynthesis, signal transduction, and antioxidant defense. Our findings reveal a considerable alteration in the proteome of B. napus leaves, as evidenced by the differential expression of key proteins involved in antioxidant responses, sulfur absorption, and herbicide tolerance. These insights not only improve our understanding of the molecular responses of B. napus to Gly treatment but also open the path towards developing targeted breeding and management techniques to enhance Gly tolerance in crops (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Plant culture and treatments

The healthy seeds of Brassica napus were obtained from the National Institute of Crop Research (NICR), Rural Development Administration (RDA), Muan, South Korea as a gift. The B. napus seeds were subjected to surface sterilization using a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 20 min, followed by thorough washing with sterile purified water three times. Subsequently, the seeds were transferred to the germination tray and placed in a controlled environment for five days, with a photoperiod of 14 h of light and 10 h of darkness, at a temperature of 25 °C. A growth chamber was used to maintain a relative humidity of 65%, and 14 h light with a light density of 150 molm− 2s− 1, 10 h darkness, with 25 °C temperature. After germination, healthy seedlings were transplanted into plastic boxes containing nutrient solutions. The seedlings were hydroponically cultivated by using the Hoagland nutrient solution15. The solution was changed every 2 days to prevent potential precipitation of nutrients, Gly and Si. The air was supplied continuously through the electric air pump in the nutrient solution for sufficient oxygen. After 21 days of cultivation, the seedlings underwent exposure to different nutrient solutions, either with or without Gly and Si: Control; Gly (40 µM); Gly (40 µM) + Si (0.5 mM), Si (0.5 mM). The experiments included three biological replicates and five technical replicates for each treatment. The plants were harvested after seven days of the treatment application. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until they were ready for molecular and biochemical analyses.

Measurement of morphological features

The shoot and root heights of the plants were measured (cm), and their fresh weights were measured with electronic balance immediately (EPG214C, Pine Brook, USA). The samples were dried and dry weights were then recorded.

Analysis of chlorophyll contents

The photosynthetic pigments concentration was determined by following a slightly modified method16. In brief, 0.04 g of plant material was homogenized with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The homogenate was incubated at 65 °C for 4 h, then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant’s absorbance was measured at 452, 644 and 663 nm. The photosynthetic pigments concentrations were calculated using the following equations17:

Measurement of ROS levels (H2O2 and O2•−)

The concentration of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was determined according to previously described method18. Superoxide (O2•−) levels were determined using the previously described extinction coefficient method19.

Analysis of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX and GST)

Leaf tissue was homogenized individually using a mortar and pestle with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The homogenate was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for enzyme activity analysis. SOD activity was measured by adding 100 µL of plant extract to a mixture containing 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.8), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.6 mM epinephrine, following the previously described protocol20. After four min, the formation of adrenochrome was recorded at 475 nm. To determine CAT activity, a mixture of 100 µL of plant extract and 6% H2O2, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was used. The absorption of the solution was measured at 240 nm at 30-second intervals, using an extinction coefficient of 0.036 mM⁻¹cm⁻¹. APX activity was assessed by mixing 0.1 mL of plant extract with 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM H2O2, 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 0.5 mM ascorbic acid with, according to the previously described method21. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 290 nm, with APX activity calculated using an extinction coefficient of 2.8 mM⁻¹cm⁻¹. GST activity was determined by adding 100 µL of the sample extract in 1.5 mM GSH, 1 mM 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) and 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.5), following the previously described method22. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 340 nm.

Extraction and measurement of proteins

Protein extraction from the tissue was conducted using a TCA/acetone-based previously described method23. Leaf samples were ground with liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. A 0.5 g sample was homogenized in a solution of 10% TCA, 0.07% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol and ice-cold acetone. The mixture was sonicated for 10 min, incubated at -20 °C for 1 h., and centrifuged at 9000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The protein pellet was washed with cold acetone, dried and reconstituted in a buffer. After 1 h at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min at 25 °C, and the protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay24.

Purification and digestion

The leaf proteins of B. napus were purified using the methanol-chloroform method25. Initially, 450 µL of water with 150 µL of chloroform were added, vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. After removing the aqueous phase, the organic phase was mixed with 450 µL of methanol. After another centrifugation under the same conditions, the supernatant was discarded. The resulting pellet was air-dried for 10 min and re-dissolved in 50 mM NH4CO3. Each sample was reduced by incubating with 50 mM DTT at 56 °C for 30 min. IAA was then added, and the samples were kept at 37 °C temperature for 30 min. Trypsin was added to the sample and incubated for 16 h, following previously described method26. To prepare the trypsin solution, 200 µL of Trypsin Resuspension Buffer (PROMEGA) was added to a vial containing 20 µg of sequencing-grade modified trypsin (porcine). The samples were purified using previously described method23, transferred to new tubes and prepared for MS analysis.

LC MS analysis

The extracted peptides were analyzed using a mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher LTQ Orbitrap, Germany) combined with an Agilent 1100 nano-flow HPLC system with a standard ion source. The setup involved two columns. A three-way tee connector was used to connect the pre-column, waste line, and analytic column (C18 AQ, 3 m, 100 m x 15 cm, Nano LC, USA). A 10 µL volume of peptide solution was loaded onto the trap column (75 μm x 2 cm, nano Viper C18, 3 μm, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two distinct solvent phases, A and B, were utilized, consisting of 0.1% formic acid (FA) in water (solvent A) and 0.1% FA in 100% ACN (solvent B). The peptides were desalted and concentrated on the trap column for 10 min using solvent (A) A fixed linear gradient over 150 min was used to elute the peptides with solvent B at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. To ensure cleanliness, the column was washed with at least ten column volumes of 100% solvent (B) Peak validity was confirmed using a standard peak shape method, considering only those peaks with well-defined symmetrical shapes as valid27. In full MS scans, the top five peaks were fragmented using data-dependent acquisition with 35% normalized collision energy. Peptide ions were introduced at 2.2 kV capillary voltage. The MS settings included a 0.5 Da mass exclusion width, 180 s dynamic exclusion, and spectra were recorded from 50 to 2000 m/z.

Validation of peptide

The MS/MS spectra were analyzed using Mascot Daemon, against the GPR database (http://www.uniprot.org.). Search parameters included a ± 1.5 Da precursor mass tolerance, ± 0.8 Da fragment mass tolerance, up to two missed trypsin cleavages, and carbamidomethyl cysteine modification. Mascot’s ion score threshold was set at 0.05, and peptide identification was validated with a 1% FDR (false discovery rate) threshold. The peptide score, calculated as -10 Log, this peptide needed a homology score with P < 0.01. Label-free quantification followed the previously described protocol28, excluding reverse decoy matches and impurities. Proteins required identification with at least two distinct peptides and quantification in at least two technical replicates across four biological replicates, with average intensities calculated for each group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used a two-sided t-test, with FDR (false discovery rate) correction for multiple comparisons, conducted in Perseus statistical software with default settings. Data were normalized by linear regression and transferred to excel for detailed analysis. Peptides matching common impurities were filtered out and at least three biological replicates were used for relative quantification and protein identification.

Analysis of bioinformatics

Gene-encoded proteins were analyzed for their cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes using the DAVID Bioinformatics (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). This DAVID tool provides a comprehensive platform for the analysis of gene lists and functional annotation, integrating various genomic resources to elucidate gene functions and their biological significance. The abundance pattern of proteins were visualized with a heatmap generated by ClustVis (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/). Fold change in protein levels between the control and the treatments was calculated by comparing the average normalized values, with p-value analysis determining significance. Upregulation and downregulation patterns were analyzed using the previously described methodology29, with a significance threshold of ≤ 0.05. Furthermore, the KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) was used to confirm the involvement of these proteins in plant molecular processes30.

Interactome analyses

Protein-protein interactions were examined with STRING database (https://string-db.org/), which classified the interactions according to the primary functions of the candidate proteins. The resulting network was visualized by Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/)31. The 3D structures of key proteins related to sulfur assimilation, antioxidant activity, and Gly tolerance were modeled using the SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) web tool. Models were chosen based on the Global Model Quality Estimation (GMQE) score, which ranges from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater confidence and accuracy in the protein models.

Data analyses

Data analysis was conducted using ANOVA, and the results are displayed as the mean of three biological replicates with standard error (SE). Comparisons between treatments were performed using Student’s t-test, considering a p-value of ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant.

Graphical presentations were generated using GraphPad Prism software (Version 9.0).

Results

Morphological features

Gly toxicity significantly inhibited the growth of B. napus, causing notable reductions in root and shoot lengths, as well as a substantial decrease in overall plant biomass. However, the addition of Si restored these characteristics (Fig. 2). Specifically, Gly toxicity reduced shoot length by 28.27% and root length by 53.13% compared to control plants. Similarly, shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, shoot dry weight, and root dry weight decreased by 53.63%, 41.29%, 27.21%, and 50.76%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Graphical abstract of Si-mediated Gly toxicity tolerance in Brassica napus. Glyphosate application inhibits the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPs), triggering mitochondrial dysfunction, the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and consequent cellular damage manifested as chlorosis, necrosis and impaired growth. In contrast, Si application under Gly stress boosts photosynthesis, biomass accumulation, growth, and nutrient uptake while alleviating chlorosis and necrosis. Proteomic analysis reveals that Si treatment activates some diverse protective mechanisms, including energy and metabolism, photosynthesis, signal transduction, antioxidant defense, cell wall and cytoskeleton, herbicide tolerance and sulfur assimilation, and plant developmental processes. Among these mechanisms, several key proteins related to antioxidant activity, sulfur assimilation, and herbicide tolerance contribute to glyphosate tolerance as confirmed by interactome analysis in the main text. The proteomic alterations enhance Gly-tolerance in Brassica napus under Si supplementation. Abbreviation, EPSPs, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Si; silicon; Gly, glyphosate.

Effect of exogenous Gly and Si on shoot length (A), Root length (B), shoot fresh weight (C), root fresh weight (D), shoot dry weight (E) and root dry weight (F) in Brassica napus seedlings with 40 µM Gly and 0.5 mM Si. Abbreviation, Gly, glyphosate, Si, silicon. Each value represents the mean of three replicates ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 among treatments by Tukey’s test.

Chlorophyll contents

Due to Gly toxicity, photosynthetic pigments, including chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll and carotenoids were drastically reduced by 62.30%, 73.56%, 65.47% and 88.50% respectively compared to seedlings under control treatments (Fig. 3A-D). Alternatively, the addition of Si to Gly (40 µM) treatment significantly restored these pigments in B. napus. Specifically, Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, total Chlorophyll and carotenoids increased by 90.68%, 73.54%, 86.97% and 191.76%, respectively, compared to Gly-treated seedlings (Fig. 3A-D).

Effect of exogenous Gly and Si on chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), total chlorophyll a + b (C), carotenoids (D), H2O2 content (E), O2•− content (F) in Brassica napus leaves. The normal growth condition (absence of Gly and Si; control), Gly (40µM), Gly + Si (40µM Gly + 0.5 mM Si), and Si (0.5 mM Si). Abbreviation, Gly, glyphosate; Si, silicon. Each value represents the mean of three replicates ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 among treatments by Tukey’s test.

Changes of H2O2 and O2•-

Under Gly stress, the H2O2 content in B. napus increased by 63.82% compared to control plants (Fig. 3E). Exogenous supplementation of Si significantly reduced H2O2 and O2•-. Additionally, the concentration of O2•- raised by 45.67% under Gly-treated plants compared to the plants under control treatments (Fig. 3F). However, the addition of Si considerably decreased O2•-, indicating that Si effectively mitigates the overproduction of O2•- under Gly stress. No significant difference was detected between the control plants and those treated exclusively with Si. These findings suggest that Si was active in response to Gly-toxicity that significantly mitigated oxidative stress in B. napus.

Changes in antioxidant enzyme activity

Compared to the control plants, Gly treatment resulted in a prominent elevation in SOD activity (Fig. 4A). Si supplementation remarkably reduced this SOD activity, whether or not Gly was present (Fig. 4A). Under Gly treatment, CAT and APX activities significantly increased compared to control plants (Fig. 4B, C). However, these activities decreased following Si supplementation, both with and without Gly treatment (Fig. 4B, C). Additionally, GST activity consistently increased under Gly treatment compared to the control (Fig. 4D). Notably, the addition of Si to Gly treatment further enhanced GST activity, whereas Si treatment alone resulted in a reduction in GST activity (Fig. 4D).

Gly-induced alterations of B. napus proteome

In B. napus, Gly-toxicity substantially altered the responses of the global leaf proteome. A proteomic approach was used to identify a total of 4407 proteins, from which many key functional proteins were screened. A proteomic approach identified a total of 4,407 proteins, among which several key functional proteins were screened. Across all treatment groups, 594 differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) were identified (Fig. 5A, Suppli. Table S3). Comparison between the control plants and the Gly-treated plants (C vs. Gly), we identified 208 DAPs, with 75 proteins showing increased abundance and 133 showing decreased abundance. In the C vs. Gly + Si comparison, 106 and 192 proteins were differentially abundant, respectively, while in the C vs. Si comparison, 27 and 61 proteins were differentially abundant (Fig. 5A).

Identification and statistics analysis of identified proteins under different treatment groups. (A) number of up or downregulated proteins between the control group and different treatments, (B) venn diagram analysis for common proteins (CP), and (C) venn diagram analysis for upregulated and downregulated proteins. Abbreviation, C, control; Gly, glyphosate; Si, silicon.

We identified a total of 2004 differentially abundant common proteins across the control, Gly, Gly + Si, and Si groups (Fig. 5B). A Venn diagram was used to display the protein abundance patterns, highlighting the upregulated and downregulated DAPs for thorough understanding (Fig. 5C, Suppli. Table S3). Particularly, the commonly identified proteins were 16 DAPs among C vs. Gly, C vs. Gly + Si, and C vs. Si treatment groups. Gly stress induced a total of 75 proteins, while Gly + Si altered 106 DAPs in B. napus. The quantified protein profile differences were visually displayed using a heatmap. These proteins were classified according to their functions within cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes (Fig. 6).

Heatmap of differentially abundant candidate proteins. The zero (0) indicates the neutral or no significant changes, while 2 value indicate the highest significant upregulation, -2 value indicates the lowest significant downregulation of candidate proteins. Abbreviation, Gly, glyphosate; Si, silicon.

GO analysis of commonly identified proteins (CIPs)

Biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components of frequently discovered proteins were displayed by Gene Ontology (GO) findings (Fig. 7A-C). In the category of biological process, proteins were associated with some functions, including translation (34%), protein folding (11%), proteasomal protein catabolic process (10%), Photosynthesis (8%), response to oxidative stress (8%), protein refolding (7%), photorespiration (6%), chaperone mediated protein folding requiring cofactor (6%), protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization 5%) and ATP synthesis coupled proton transport (5%) (Fig. 7A, Suppli. Table S4). Likewise, in cellular component analyses category, the proteins showed the significant association, including cytoplasm (29%), chloroplast (16%), cytosol (12%), nucleosome (10%), mitochondrion (8%), cytosolic large ribosomal subunit (6%), cytosolic small ribosomal subunit (5%), chloroplast thylakoid membrane (5%), ribosome (5%) and proteasome core complex (4%) (Fig. 7B, Suppli. Table S4). In molecular function category, the identified proteins were associated with some functions, including structural constituent of ribosome (22%), RNA binding (15%), protein heterodimerization activity (15%), oxidoreductase activity (9%), ATPase activity (8%), mRNA binding (8%), peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity (6%), hydrolase activity, acting on ester bonds (6%), pyridoxal phosphate binding (6%), and serine-type endopeptidase activity (5%) (Fig. 7C, Suppli. Table S4).

The result of GO analysis showed the commonly identified differentially abundant proteins were significantly affected by Gly stress. According to the DAVID Bioinformatics analysis, a total of 2004 proteins exhibited alterations with 43 KEGG pathways correspondence (Suppli. Table S2). These proteins were associated with various metabolic pathways, including general metabolic pathways (bna01100) involving 817 proteins, carbon metabolism (bna01200) involving 214 proteins, amino acid biosynthesis (bna01230) involving 142 proteins, ribosome function (bna03010) involving 279 proteins, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis (bna01110) involving 419 proteins (Suppli. Table S2).

GO analysis of differentially abundant proteins (DAPs)

The relation of DAPs to various biological process were revealed through GO analysis (Suppli. Table S1). In the category of biological process, the DAPs were associated with some processes, including translation (40 DAPs), protein folding (13 DAPs), proteasomal protein catabolic process (12 DAPs), photosynthesis (10 DAPs), response to oxidative stress (9 DAPs), protein refolding (8 DAPs), and photorespiration (7 DAPs). (Fig. 8, Suppli. Table S5). In cellular component category, cytoplasm (82 DAPs), chloroplast (44 DAPs), cytosol (33 DAPs), nucleosome (29 DAPs), mitochondrion (21 DAPs), cytosolic large ribosomal subunit (16 DAPs), cytosolic small ribosomal subunit (15 DAPs), chloroplast thylakoid membrane (13 DAPs) and ribosome (13 DAPs) displayed the leading categories (Fig. 8, Suppli. Table S5). In the category of molecular functions, GO terms of DAPs displayed important enrichment, including structural constituent of ribosome (41 DAPs), RNA binding (28 DAPs), protein heterodimerization activity (27 DAPs), oxidoreductase activity (16 DAPs), ATPase activity (14 DAPs), mRNA binding (14 DAPs), peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity (12 DAPs), hydrolase activity, acting on aster bonds (12 DAPs), and pyridoxal phosphate binding (12 DAPs) (Fig. 8, Suppli. Table S5).

The GO functions of differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) involved in different physiological process in Brassica napus leaves in response to Gly and Si. Abbreviation, BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; and MF, molecular function. The bar chart was constructed through the DAVID bioinformatics platform.

KEGG pathways of CIPs and DAPs

The impact of Gly stress on leaf metabolism in B. napus seedlings was examined by constructing a potential metabolic pathway using the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/; accessed on January 24, 2024). DAPs and CIPs were the key components for developing this pathway. The dot plot visualized the KEGG pathways with the highest enrichment (Fig. 9A, B).

Dot plot of the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for (A) common identified proteins (CIPs) and (B) differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) in Brassica napus seedlings in response to Si-mediated Gly stress. The horizontal axis represents the enrichment rate of the input proteins in the pathway, while the vertical axis represents the name of pathways. The color scale indicates different thresholds of the p-value, and the size of the dot indicates the number of proteins corresponding to each term. The bubble map was constructed through the Science and Research Plot platform (https://tinyurl.com/pve3dtnw).

In all treatment groups of CIPs, the KEGG pathways that showed the highest enrichment were identified as follows: metabolic pathways (bna01100) with 817 proteins, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (bna01110) with 419 proteins, ribosome (bna03010) with 279 proteins, carbon metabolism (bna01200) with 214 proteins, biosynthesis of amino acids (bna01230) with 142 proteins, photosynthesis (bna00195) with 96 proteins, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (bna00710) with 90 proteins, biosynthesis of cofactors (bna01240) with 87 proteins, oxidative phosphorylation (bna00190) with 85 proteins, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (bna00010) with 84 proteins, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (bna00630) with 80 proteins, cysteine and methionine metabolism (bna00270) with 67 proteins, and pyruvate metabolism (bna00620) with 62 proteins. (Suppli. Table S2).

In all DAPs treatment groups, the pathways that showed the highest enrichment were identified as follows: metabolic pathways (bna01100) with 69 proteins, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (bna01110) with 41 proteins, ribosome (bna03010) with 23 proteins, carbon metabolism (bna01200) with 17 proteins, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (bna00630) with 11 proteins, biosynthesis of amino acids (bna01230) with 11 proteins, proteasome (bna03050) with 8 proteins, cysteine and methionine metabolism (bna00270) with 8 proteins, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism (bna00250) with 6 proteins, fatty acid metabolism (bna01212) with 6 proteins, glycine, serine and threonine metabolism (bna00260) with 6 proteins, peroxisome (bna04146) with 6 proteins, and arginine biosynthesis (bna00220) with 5 proteins (Suppli. Table S6).

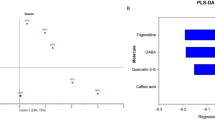

Protein network

Interactions between proteins offer crucial biological insights into the processes occurring within B. napus. The analysis of these interactions was facilitated by the tool STRING, which categorized the proteins based on their functions. Within the category of energy-metabolism-related proteins (Table 1), the protein ATP synthase subunit O (BnaC09g43620D, A0A078F9W7) was found to interact within a network that A0A078DNQ5, A0A078FXT7, A0A078FR19, A0A078GFM5, A0A078H5Q9 and A0A078FQR6 (Fig. 10A). The photosynthesis category (Table 1) exhibited that photosystem I reaction center subunit II (BnaA09g01080D, A0A078G9Q8) sharing the protein network with A0A078J8I6, A0A078G7F6, A0A078I263, A0A078GY42 and A0A078GLT1 (Fig. 10B). The category of signal transduction (Table 1) displayed a significant interactions, where the protein (BnaA04g15900D, A0A078H195) exhibited a protein network sharing with A0A078FWF3, A0A078IT30, A0A078HEE7, A0A078HCR8, A0A078F7P2, A0A078FXI3, A0A078IMT1, A0A078F1F5, A0A078FJL5, A0A078GTV5, A0A078F3D0 and D1L8S1 (Fig. 10C). In protein categories (Table 1) antioxidant, sulfur assimilation and herbicide tolerance, the L-ascorbate peroxidase (BnaAnng04450D, A0A078HFK7) protein showed a share network with GPX 2 (BnaCnng27540D, A0A078IXA9), superoxide dismutase (BnaC03g16120D, A0A078H5C3), and probable phospholipid hydroperoxide GPX 6 (BnaA02g21680D, A0A078GL08) (Fig. 10D). Interactome of six candidate proteins related with sulfur assimilation and herbicide tolerance, and antioxidant, including L-ascorbate peroxidase (A0A078HFK7, BnaAnng04450D), superoxide dismutase (A0A078H5C3, BnaC03g16120D), glutaredoxin-C2 (A0A078HHH4, BnaC04g32420D), peroxidase (A0A078IWR4, BnaAnng12900D), GPX 2 (A0A078IXA9, BnaCnng27540D) and peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase A3 (A0A078JHR9, BnaC09g47890D) were shared protein networks by being mapped and analyzed within different protein interaction networks. This approach facilitated the identification of key interactions and functional roles across multiple biological contexts (Fig. 11A-F).

Protein interactome analysis of differentially abundant proteins (A) energy and metabolism, (B) photosynthesis, (C) signal transduction and (D) antioxidant, sulfur assimilation and herbicide tolerance related proteins identified in leaves of Brassica napus seedlings exposed to Si-mediated Gly stress.

Protein-protein interaction of candidate proteins involving antioxidant, sulfur assimilation and herbicide tolerance processes in Brassica napus. (A) L-ascorbate peroxidase (A0A078HFK7, BnaAnng04450D), (B) Superoxide dismutase (A0A078H5C3, BnaC03g16120D), (C) glutaredoxin-C2 (A0A078HHH4, BnaC04g32420D), (D) peroxidase (A0A078IWR4, BnaAnng12900D), (E) glutathione peroxidase 2 (A0A078IXA9, BnaCnng27540D) and (F) peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase A3 (A0A078JHR9, BnaC09g47890D).

Discussion

The study offers proteome insights into the mechanisms underlying Si-mediated protection against Gly toxicity in B. napus. We observed Gly-induced toxicity leads to the generation of excess ROS consequently increasing the oxidative stress, and negatively affecting the morphological and physiological characteristics of the B. napus seedlings. However, addition of Si restored the oxidative stress. In our study, Si restored the pigments of photosynthesis as well as increased GST activity. A relationship exists between the pigments of light-harvest and efficiency of photosynthesis, which in turn enhances growth and development in B. napus32. Therefore, Si is crucial in restoring the pigments of photosynthesis in B. napus under Gly-toxicity. Additionally, the minimization of Gly-induced oxidative stress indicators (O2•−, H2O2) in response to Si supplementation indicates that Si actively reduces oxidative stress in plants under Gly stress. This reduction in oxidative stress is achieved through the ability of Si to enhance antioxidant activity, thereby improving plant tolerance to abiotic stress33.

GO and KEGG analysis are vital for proteomic studies as they provide comprehensive insights into the functional roles and pathways associated with identified proteins. The analysis of functional categories for 130 DAPs suggests their involvement in diverse biological processes, including energy and metabolism, photosynthesis, signal transduction, antioxidant, cell wall functions, herbicide tolerance and sulfur assimilation, and plant development. In the subsequent categories, we explored all mechanisms and interpretations, highlighting results that either align or differ from those observed in other plant species when compared to B. napus.

Energy and metabolism-related proteins

Plants produce carbohydrates through photosynthetic CO2 fixation, which serve as substrates for various functions, including energy metabolism, secondary metabolism, growth, development, and stress responses. Proper regulation of photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism is crucial for plant growth, development, and stress adaptation, especially in a changing environment34. Energy production from carbohydrates is vital for supporting metabolic processes and the growth of plants. Studies have demonstrated a connection between elevated glucose storage and improved resilience to metal stress in several plant species35.

In this research, we identified 35 DAPs engaged in citric acid cycle and the metabolism of carbohydrate. Plants have developed intricate regulatory mechanisms to regulate glycolysis pathways and the TCA cycle, ensuring efficient energy production and metabolic adaptation during environmental stress. These pathways are fine-tuned to optimize resource utilization and maintain cellular homeostasis under abiotic stresses36. The increase in proteins associated with glycolysis suggests the B. napus seedlings can maintain critical respiration processes and produce more ATP through enhanced glycolytic activity under Gly stress. Si application enhances the ability of plants to mitigate toxic effects on cellular components through cellular homeostasis.

Proteins such as NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12, NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit U, and pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit, which are engaged in the citric acid cycle, help maintain cellular energy production and metabolic balance under Gly stress. These results align with findings from a proteomic study on the roots of Oenothera glazioviana under the stress of Cu37. Collectively, these proteins engaged in the citric acid cycle, along with the beneficial effects of Si supplementation on antioxidant activity, metabolic pathways, and plant physiology, contribute to Gly stress tolerance in B. napus.

Photosynthesis-related proteins

Plants regulate their photosynthetic capacity in response to environmental conditions, optimizing yield and overall growth and development34. Gly-toxicity markedly inhibits photosynthesis and plant growth by immobilizing essential micronutrients required for chlorophyll formation and photosynthesis and disrupting physiological processes and cell metabolism38,39. In our study, we observed unique response patterns of differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) associated with photosynthesis, particularly those involved in the Calvin cycle and the electron transport chain, under Gly stress. The detrimental effects of Gly on photosynthesis have also been documented in willow plants38.

The reduced abundance of leaf proteins, such as ribulose bisphosphate, indicates that energy metabolism and carbon fixation processes are significantly impaired in B. napus Gly toxicity, likely due to diminished gas exchange capacity40. These findings indicate that Gly toxicity impairs photosynthetic machinery. Additionally, our study suggests that Gly or Gly + Si induced proteomic regulations did not show similar abundance patterns. However, physiological analysis confirmed that Si restored the content of photosynthetic pigments.

Thus, the proteomic alterations induced by Gly + Si suggest that Si actively responds even under Gly stress. The findings suggest that increased energy generation is necessary for B. napus under Gly stress in order to activate carbon fixation. The higher abundance of these potential proteins under Gly stress indicates that they may have a role in supporting B. napus plants by encouraging better growth and development.

Signal transduction

Signaling pathway is crucial for mobilizing defense mechanisms against toxic substances in the plants41. This proteomic study examines Gly-associated signal alterations and the metabolism of differentially abundant proteins. We discovered that the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP28 is upregulated, while CYP18-3 is downregulated. Both of these enzymes play a crucial role in speeding up the cis-trans isomerization of proline imidic peptide bonds in oligopeptides, aiding in protein folding. Stress signals triggered by protein kinases lead to changes in gene expression, resulting in the upregulation of CYP28 and downregulation of CYP18-3, contributing to Gly stress tolerance in B. napus. Additionally, we identified an upregulated GTP-binding protein SAR1A. The upregulation of SAR1A by Gly treatment suggests it functions as a molecular switch in signal transduction cascades, contributing to Si-mediated Gly stress tolerance in B. napus. Comparable results were found in a proteomic study of glyphosate-induced oxidative stress in rice leaves42.

Antioxidant-related proteins

Several stress-related and defensive proteins, along with vital antioxidant enzymes, play crucial roles in defending plant mechanisms, and enhancing stress tolerance43. In this current study, nine DAPs were identified under the stress of Gly. Among these, one SOD, one CAT, and one APX showed notable upregulation in response to Gly and Si exposure. SOD and APX are key players in ROS detoxification in plant cells. SOD, the first enzyme in the detoxification process, converts superoxide anion (O2•−) to H2O2, while APX reduces H2O2 to water using ascorbic acid as an electron donor44. Comparable results were found in a proteomic study of glyphosate-induced oxidative stress in rice leaves42.

Two possible ways that Si reduces abiotic stress are by controlling ROS levels and enhancing antioxidant metabolism45. Our results revealed that Gly induced ROS were successfully regulated by enhanced activities of DAPs and key antioxidants (SOD, APX, CAT). This indicates that the antioxidant defense system was completely operational under Gly stress, further enhancing Gly tolerance in B. napus through exogenous Si supplementation.

Cell wall-related proteins

Cell wall and cytoskeleton related proteins cause rapid changes due to Gly exposure. The cell wall acts as the primary mechanism against abiotic stressors such as Gly toxicity, acting as a barrier and undergoing modifications when under stress. We identified eight differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) under Gly stress. Among these proteins, the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein family, which cleaves and reconnects xyloglucan molecules, plays a crucial role in cell wall synthesis, reconstruction, and stress resistance. This supports findings in poplar plants that show tolerance to abiotic stress, such as salt stress46. Our results indicate that Si-mediated tolerance to Gly stress involves the processing of proteins associated with the cell wall.

Herbicide tolerance and sulfur assimilation

Sulfur (S) is crucial for regulating plant tolerance to glyphosate47. In our B. napus proteome research, we identified thirteen key proteins involved in herbicide tolerance and sulfur assimilation processes, which enhance development and growth of B. napus under Gly toxicity. We noted increased levels of proteins associated with sulfur assimilation, which aid in incorporating sulfur into compounds such as methionine and GSH, thereby enhancing Gly tolerance in B. napus. The role of Si in mitigating Gly toxicity has also been observed in tomato plants, highlighting its protective effects against Gly-induced stress5. Among these proteins, three peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase proteins, which catalyze the reduction of methionine sulfoxide to methionine, play a protective role against oxidative stress48. In this current study, the minimization of H2O2 and O2•− in response to Si supplementation suggests that involvement of Si in Gly tolerance is linked to its availability in B. napus. Additionally, the significant upregulation of these three DAPs indicate the role of Si in facilitating sulfur-mediated Gly tolerance in B. napus.

Plant development-related proteins

We identified seven DAPs associated with plant growth and development. Notably, early nodulin-like protein 1 was significantly upregulated, which plays a critical role in regulating translation processes within plants. This protein plays the crucial role under stress responses, as validated by a combined transcriptome and proteome approach in pigeon pea49. In our investigation, this heightened synthesis of protein, activated by silicon, enhances the cellular defensing ability against Gly toxicity and promotes overall growth of the plants.

Unknown proteins

Several unknown proteins, such as uncharacterized protein At5g39570-like, uncharacterized BNAA03G49580D, and uncharacterized LOC106361260, showed increased responses, while uncharacterized LOC106429057, uncharacterized BNAC06G13920D, uncharacterized LOC106452857, and uncharacterized LOC106433592 exhibited decreased responses under Gly stress. The precise biological functions of these proteins are currently unknown. However, our research observed their responses to Gly and/or Si supplementation. Further investigation is necessary to uncover their specific biological functions related to Gly-stress tolerance.

Protein interactome analysis

The activity of a protein is often significantly influenced by its interactions with other proteins and regulatory modifications50. Protein-protein interactions are crucial for various biological processes, such as cell-to-cell communication and the regulation of metabolic processes51. The functions of the target protein can be predicted by examining its co-expression patterns and interactome analysis. Typically, the desired phenotypic traits are often produced by a series of molecular alterations caused by the interaction of genes and proteins52. Gaining insight into the protein interactome helps to understand the biochemical interactions, cellular signaling and signal transduction among B. napus leave’s diverse protein composition. Within the energy and metabolism category, some proteins, including pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit, acetyl-CoA carboxytransferase, NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit U, and NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit M are interconnected, contributing to the overall energy balance and metabolic activities within plant cells during the stress conditions. This method highlights their important contribution to plant’s metabolic processes and energy53.

The proteins related to photosynthesis, such as chlorophyll a-b binding protein, chlorophyll a-b binding protein 1, chlorophyll a-b binding protein CP26, photosystem I reaction center subunit II and subunit VI-1, photosystem II stability/assembly factor HCF136, and RuBisCo small subunit, are directly related with photosynthesis process and CO2 assimilation through the mutual interactions of that proteins.

Some proteins such as 60 S ribosomal protein L7-3, L13a-4, L18a-2-like, and 40 S ribosomal protein S3-2-like, S5-1, S16-3-like, and S7 are engaged with the process of metabolism and signal transduction. Additionally, the interactome analysis of antioxidant, sulfur assimilation, and herbicide tolerance proteins, counting L-ascorbate peroxidase, GPX 2, superoxide dismutase, and phospholipid hydroperoxide GPX 6, facilitated functional protein interactions associated with stress defense, translation, and sulfur assimilation processes in Brassica juncea54.

Determining how interrelated protein networks react to Gly toxicity reveals their possible functions and connections in plants facing Gly stress. This investigation reveals shared networks among candidate proteins involved in mitigating Gly stress in B. napus. The widespread use of herbicides causes oxidative stress in plants despite their weed control benefits. However, they also have negative side effects on main crops. Interactome analysis of key antioxidant defense and herbicide (Gly) tolerance proteins in B. napus showed that L-ascorbate peroxidase and superoxide dismutase interact with proteins involved in ascorbate and Si metabolism, enhancing the plant’s antioxidant capacity and mitigating Gly-induced oxidative stress. These enzymes play a crucial role in scavenging ROS43. Peroxidase degrades H2O2 to alleviate oxidative stress, while GPX utilizes peroxidase as electron acceptors to reduce oxidative damage55.

Glutaredoxins are oxidoreductases with electrostatic properties relevant for protein-protein interactions required for oxidoreductase activity56. These enzymes catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions by facilitating electron transfer between donor and acceptor molecules, participating in metabolic processes such as cellular respiration, photosynthesis, and detoxification. GRX plays a critical role in maintaining thiol-redox homeostasis and mediating redox signal transduction. Disruptions in the Grx system have been linked to the development and progression of various oxidative stress-related diseases, highlighting its importance in cellular redox balance and signaling pathways57. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase interacts with proteins that protect against oxidative stress by inactivating methionine oxidation48. In this current study, we found that these proteins are essential for reducing oxidative stress caused by Gly and improving Gly tolerance in B. napus by exogenous addition of Si.

Conclusion

The research impact explores the proteomic insights of Si-mediated Gly-toxicity mitigation in B. napus. This study further highlights the urgent need for environmentally sustainable strategies to address Gly toxicity. In this study, the Si supplementation as a potential method to mitigate Gly toxicity in B. napus leaves provided promising results, revealing substantial alterations in protein expression profiles. Particularly the identification of key target proteins connected to antioxidant defense, herbicide tolerance and sulfur assimilation processes through interactome analyses. These findings enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying plant responses to Gly stress and offer valuable insights into tolerance pathways. Collectively, these results lay the groundwork for further in-depth field studies to elucidate the molecular basis of Gly stress responses and explore the potential of Si in mitigating Gly toxicity in B. napus.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis used a two-sided t-test, with FDR (false discovery rate) correction for multiple comparisons, conducted in Perseus statistical software with default settings. Data were normalized by linear regression and transferred to Excel for detailed analysis. Peptides matching common impurities were filtered out, and at least three biological replicates were used for relative quantification and protein identification.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Benbrook, C. M. Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environ. Sci. Eur. 28(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-016-0070-0 (2016).

Sang, Y., Mejuto, J. C., Xiao, J. & Simal-Gandara, J. Assessment of glyphosate impact on the agrofood ecosystem. Plants 10(2), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020405 (2021).

Kanissery, R., Gairhe, B., Kadyampakeni, D., Batuman, O. & Alferez, F. Glyphosate: its environmental persistence and impact on crop health and nutrition. Plants 8(11), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8110499 (2019).

Ahmed, S. R. et al. Potential role of silicon in plants against biotic and abiotic stresses. Silicon 15, 3283–3303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-022-02254-w (2023).

Soares, C. et al. Silicon improves the redox homeostasis to alleviate glyphosate toxicity in tomato plants- are nanomaterials relevant? Antioxidants 10(8), 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10081320 (2021).

Basu, S. & Kumar, G. Exploring the significant contribution of silicon in regulation of cellular redox homeostasis for conferring stress tolerance in plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 166, 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.005 (2021).

Jia, H. et al. Proteome dynamics and physiological responses to short-term salt stress in Brassica napus leaves. PLoS One. 10(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144808 (2015). e0144808.

Raboanatahiry, N., Li, H., Yu, L. & Li, M. Rapeseed (Brassica napus): processing, utilization, and genetic improvement. Agronomy 11(9), 1776. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11091776 (2021).

Kashyap, A. et al. Morpho-biochemical responses of Brassica coenospecies to glyphosate exposure at pre- and post-emergence stages. Agronomy 13(7), 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13071831 (2023).

Koh, J. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of Brassica napus in response to drought stress. J. Proteome Res. 14(8), 3068–3081. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr501323d (2015).

Hu, M. et al. Comparative proteomic and physiological analyses reveal tribenuron-methyl phytotoxicity and nontarget‐site resistance mechanisms in Brassica napus. Plant. Cell. Environ. 46(7), 2255–2272. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14598 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Proteomics: a powerful tool to study plant responses to biotic stress. Plant. Methods. 15(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0515-8 (2019).

Fu, J. et al. Label-free proteome quantification and evaluation. Brief. Bioinform. 24, bbac477. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac477 (2023).

Yan, S., Bhawal, R., Yin, Z., Thannhauser, T. W. & Zhang, S. Recent advances in proteomics and metabolomics in plants. Mol. Hortic. 2, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43897-022-00038-9 (2022).

Hoagland, D. R. & Arnon, D. I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Circular Calif. Agricultural Exp. Stn. 347 (1950).

Ritchie, R. J., Sma-Air, S. & Phongphattarawat, S. Using DMSO for chlorophyll spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phycol. 33, 2047–2055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-021-02438-8 (2021).

Metzner, H., Rau, H. R. & Senger, H. Untersuchungen zursynchronisierbar kein einzelner pigment-mangelmutanten Von Chlor-Ella. Planta 65, 186–194 (1965). http://www.jstor.org/stable/23365689

El-Shehawi, A. M., Rahman, M. A., Elseehy, M. M. & Kabir, A. H. Mercury toxicity causes iron and sulfur deficiencies along with oxidative injuries in alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Plant. Biosyst. 156, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2021.1985005 (2022).

Hu, L., Li, H., Pang, H. & Fu, J. Responses of antioxidant gene, protein and enzymes to salinity stress in two genotypes of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) differing in salt tolerance. J. Plant. Physiol. 169(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2011.08.020 (2012).

Goud, P. B. & Kachole, M. S. Antioxidant enzyme changes in neem, pigeonpea and mulberry leaves in two stages of maturity. Plant. Signal. Behav. 7, 1258e1262. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.21584 (2012).

Almeselmani, M., Deshmukh, P. S., Sairam, R. K., Kushwaha, S. R. & Singh, T. P. Protective role of antioxidant enzymes under high temperature stress. Plant. Sci. 171, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.04.009 (2006).

Hossain, M. A., Hossain, M. Z. & Fujita, M. Stress-induced changes of methylglyoxal level and glyoxalase I activity in pumpkin seedlings and cDNA cloning of glyoxalase I gene. Aust J. Crop Sci. 3, 53–64 (2009). https://www.cropj.com/Fujita_3_2_2009.pdf

Roy, S. K. et al. Proteome characterization of copper stress responses in the roots of sorghum. BioMetals 30, 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-017-0045-7 (2017).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Komatsu, S. et al. Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis of abscisic acid effect in early-stage soybean under flooding. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4769–4784. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr4001898 (2013).

Sharmin, S. A. et al. Mapping the leaf proteome of Miscanthus sinensis and its application to the identification of heat-responsive proteins. Planta 238, 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-013-1900-6 (2013).

Pasrawin, T., Kazuyoshi, Y. & Yasushi, I. Peak identification and quantification by proteomic mass spectrogram decomposition. J. Proteome Res. 20(5), 2291–2298. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00819 (2021).

Shinoda, K., Tomita, M. & Ishihama, Y. emPAI calc—for the estimation of protein abundance from large-scale identification data by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Bioinformatics 26, 576–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp700 (2010).

Aguilan, J., Kulej, K. & Sidoli, S. Guide for protein fold change and p-value calculation for non-experts in proteomics. Mol. Omics. 16, 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0MO00087F (2020).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishigoro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acid Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D607–D613. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1131 (2019).

Jin, H. et al. Optimization of light harvesting pigment improves photosynthetic efficiency. Plant. Physiol. 172(3), 1720–1731. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.16.00698 (2016).

Kim, Y. H., Khan, A. L., Waqas, M. & Lee, I. J. Silicon regulates antioxidant activities of crop plants under abiotic-induced oxidative stress: a review. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 510. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00510 (2017).

Herrmann, H. A., Schwartz, J. M. & Johnson, G. N. Metabolic acclimation- a key to enhancing photosynthesis in changing environments? J. Exp. Bot. 70(12), 3043–3056. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erz157 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Dissecting root proteome changes reveals new insight into cadmium stress response in radish (Raphanus sativus L). Plant. Cell. Physiol. 58, 1901–1913. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcx131 (2017).

Yu, W., Gong, F., Cao, K., Zhou, X. & Xu, H. Multi-omics analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms of the glycolysis and TCA cycle pathways in Rhododendron Chrysanthum Pall. Under UV-B stress. Agronomy 14, 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14091996 (2024).

Wang, C., Wang, J. & Wang, X. Proteomic analysis on roots of Oenothera glazioviana under copper-stress conditions. Sci. Rep. 7, 10589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10370-6 (2017).

Gomes, M. P. et al. Differential effects of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) on photosynthesis and chlorophyll metabolism in willow plants. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 130, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.11.010 (2016).

Luiz, H. S. Z., Robert, J. K., Rubem, S. O. J. & Jamil, C. Glyphosate affects chlorophyll, nodulation and nutrient accumulation of second generation glyphosate-resistant soybean (Glycine max L). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 99(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.11.010 (2011).

Mateos-Naranjo, E., Redondo-Gómez, S., Cox, L., Cornejo, J. & Figueroa, M. E. Effectiveness of glyphosate and imazamox on the control of the invasive cordgrass Spartina densiflora. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 72(6), 1694–1700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2009.06.003 (2009).

Lin, C. Y. et al. Comparison of early transcriptome responses to copper and cadmium in rice roots. Plant. Mol. Biol. 81, 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-013-0020-9 (2013).

Ahsan, N. et al. Glyphosate-induced oxidative stress in rice leaves revealed by proteomic approach. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 46(12), 1062–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.07.002 (2008).

Singh, D. et al. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide alleviates chromium toxicity by modulating chromium, nutrients and reactive oxygen species accumulation, and antioxidant defence system in mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) seedlings. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 200, 107767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107767 (2023).

Sharma, P., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S. & Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/217037 (2012).

Van Bockhaven, J. et al. Silicon induces resistance to the brown spot fungus Cochliobolus miyabeanus by preventing the pathogen from hijacking the rice ethylene pathway. New. Phytol. 206(2), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2023.2236105 (2015a).

Cheng, Z. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene family in poplar. BMC Genom. 22(1), 804. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-08134-8 (2021).

Petineli, R., Moraes, L. A. C., Heinrichs, R., Moretti, L. G. & Moreira, A. Conventional and transgenic soybeans: physiological and nutritional differences in productivity under sulfur fertilization. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2020.1822387 (2020).

Zhao, W. et al. Interaction of wheat methionine sulfoxide reductase TaMSRB5.2 with glutathione S-transferase TaGSTF3-A contributes to seedling osmotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 194, 104731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104731 (2022).

Awana, M. et al. Protein and gene integration analysis through proteome and transcriptome brings new insight into salt stress tolerance in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 3589–3602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.223 (2020).

Alaeddine, S. et al. Phase separation-based visualization of protein–protein interactions and kinase activities in plants. Plant. Cell. 35(9), 3280–3302. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koad188 (2023).

Braun, P. & Gingras, A. C. History of protein-protein interactions: from egg-white to complex networks. Proteomics 12, 1478–1498. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201100563 (2012).

Rao, V. S., Srinivas, K., Sujini, G. N. & Kumar, G. N. S. protein-protein interaction detection: methods and analysis. Int. J. Proteom. 2014, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/147648 (2014).

Sato, M., Torres-Bacete, J., Sinha, P. K., Matsuno-Yagi, A. & Yagi, T. Essential regions in the membrane domain of bacterial complex I (NDH-1): the machinery for proton translocation. J. Bioenerg Biomembr. 46, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10863-014-9558-8 (2014).

Sehrawat, A., Sougrakpam, Y. & Deswal, R. Cold modulated nuclear S-nitrosoproteome analysis indicates redox modulation of novel Brassicaceae specific, myrosinase and napin in Brassica juncea. Environ. Exp. Bot. 161, 312–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.010 (2019).

Pandey, V. P., Awasthi, M., Singh, S., Tiwari, S. & Dwivedi U.N. A comprehensive review on function and application of plant peroxidases. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 6(1), 308. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1009.1000308 (2017).

Couturier, J., Jacquot, J. P. & Rouhier, N. Toward a refined classification of class I dithiol glutaredoxins from poplar: biochemical basis for the definition of two subclasses. Front. Plant. Sci. 4, 518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00518 (2013).

Chai, Y. C. & Mieyal, J. J. Glutathione and glutaredoxin-key players in cellular redox homeostasis and signaling. Antioxidants 12(1553). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2014.12.014 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge to NIIED (National Institute for International Education), Ministry of Education, Republic of Korea for supporting as Global Korea Scholarship (GKS-2020). This work was supported by a funding for the academic research program of Chungbuk National University in 2024. The work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Project no. 2018R1D1A1B07050661).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K.M, S.-H.W., M.A.R. and S.K.R. Conceptualization, Design of the study. S.H.Y. and K.C. LC MS/MS analysis. P.K.M. Data analysis, write the original draft. S.-J.K. Technical assistance. P.K.M, M.A.R. and S.K.R. Data visualization. A.M., M.A.R. and S.K.R. Writing, reviewing, and editing the original draft. P.K.M, M.Z., T.K.-T., S.W.C and S.-H.W. subsequent revisions of the drafts and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Brassica napus variety ‘jungmo7001’ was provided by National Institute of Crop Research (NICR), Rural Development Administration (RDA), Muan, South-Korea. The variety, which was developed by NICR, RDA and registered as the registration number of 5782, was used in accordance with the plant variety protection and seed act of South-Korea. The plant resource can be accessed via KOREA SEED & VARIETY SERVICE (https://tinyurl.com/49c629av).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mittra, P.K., Rahman, M.A., Roy, S.K. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals the roles of silicon in mitigating glyphosate-induced toxicity in Brassica napus L.. Sci Rep 15, 2465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87024-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87024-5