Abstract

To address the limitations of the original algorithm, several optimization techniques are proposed. This article presents an original RRT*-Connect algorithm for the planning of obstacle avoidance paths on robotic arms. These strategies include implementing a target biasing algorithm, using elliptic space sampling to enhance the sampling process, the revision of the cost function to better guide path planning, and implementing an artificial potential field and gradient descent strategy to design adaptive step sizes. Furthermore, the use of segmented Bézier curves facilitates the generation of a more fluid trajectory when constructing the final path. The effectiveness of these augmentation strategies is corroborated by both simulations and experimental verification on a robotic arm. The simulations showed a 19.39% reduction in average run time and a 5% reduction in average path length compared to the existing RRT*-Connect algorithm. Therefore, The enhanced algorithm meets the requirement for optimal obstacle avoidance path planning by consistently finding the shortest path while avoiding obstacles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithm is a classic heuristic path-planning algorithmused in complex environments for autonomous systems such as robots, drones, and robotic arms. The core ideais to construct a tree-like structure representing feasible paths through random sampling and iterative expansion, enabling rapid exploration in high-dimensional state spaces1. RRT significantly differs from traditional path-planning algorithms like A*, as it builds a continuously growing tree structure through random sampling and expansion, efficiently exploring unknown regions. This capability RRT to handle high-dimensional state spaces and dynamic obstacles effectively, making it computationally efficient and suitable for real-time decision-making scenarios2. Unlike optimization-based algorithms, RRT’s strength lies in its randomness and adaptability, allowing it to find suitable paths in complex environments3. Given the complexities involved in robotic arm obstacle avoidance, including motion constraints and environmental distribution, RRT’s rapid random exploration and adaptive expansion characteristics make it well-suited for robotic arm path planning, leading to its extensive application and research in this field4.

Researchers have made significant stridespractical Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithms, focusing on improving convergence and sampling efficiency, path quality, adaptability to dynamic environments, obstacle avoidance, and multi-objective path planning. Approaches like Q-RRT*5, Selective Target Sampling RRT6, and metaheuristic-based RRT7have improved solution quality and convergence speed by integrating sampling strategies and graph pruning. Techniques such as RRT-Connect, RRT-Extending, and algorithms like RDP8and B-spline curves9have improved path smoothness and constraint compliance. Variants like RRT*-Smart and Informed RRT* have addressed dynamic environment adaptability10and obstacle avoidance11,12. Multi-objective path planning capabilities have been expanded through methods like Bi-RRT13and RRT*-goal-biased14,15, with researchers employing hybrid approaches and enhanced genetic algorithms. While theoretical optimality remains a challenge16, ongoing research continues to promise improvements, expanding the applicability of RRT algorithms across various robotic path planning scenarios17.

Path planning algorithms are of significant importance in current research and practical applications, particularly in the field of robot control. These algorithms help intelligent systems, such as robots, in finding optimal or suitable paths to reach goals or avoid obstacles, thereby enhancing system efficiency and safety18. In the context of robotic arm obstacle avoidance research, path planning algorithms play a crucial role in determining the motion trajectories of robotic arms in complex environments, ensuring safe and efficient operation. Commonly used path planning algorithms can be categorized into types such as search algorithms, sampling-based algorithms, and smoothing algorithms19.

In practical applications, one must consider multiple algorithm types, assess their strengths and weaknesses, and select or combine them as needed to achieve to achieve efficient path planning.The algorithm’s speed and accuracy, while stability can be assessed by its ability to handle unexpected obstacles. Safety can be evaluated based on its ability to avoid collisions20. In the realm of robotic arm obstacle avoidance path planning, the use of random sampling algorithms like RRT has become prevalent21,22,23. This article delves into the performance of Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithms in robotic arm obstacle avoidance path planning. It offers a concise introduction to the foundational principles of traditional RRT algorithms, followed by an in-depth analysis and optimization of these algorithms.

Preliminaries

The current RRT*-Connect algorithm efficiently performs dual-tree path planning, rapidly identifying the optimal path between the start and target points in complex environments24. However, the algorithm has certain limitations. For instance, the sampling process exhibits a high degree of randomness, potentially leading to redundant and inefficient search paths. Additionally, in the parent node reselection phase, cost calculations typically rely on factors like Euclidean distances between nodes in the RRT* algorithm25, which may not fully consider obstacle interactions and path complexity. Furthermore, the fixed node expansion step sizes in the current RRT*-Connect algorithm may result in the neglect of potentially effective paths during the search process.

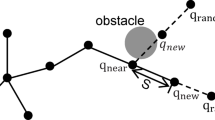

Abhishek Kumar Kashyap et al.26 proposed a hybrid approach combining DWA and TLBO algorithms to optimize path planning and obstacle avoidance in complex dynamic environments, focusing on achieving efficient obstacle avoidance under multiple constraints. Inspired by their work, this paper seeks to enhance the RRT*-Connect algorithm through several key strategies. Firstly, the sampling process is optimized using goal-biased sampling and restricting random sampling to specific regions. Secondly, a redesigned cost function is introduced for parent node reselection, incorporating considerations such as obstacle intersection areas and the mechanical constraints of robotic arm motion. This enhanced cost function enables a more comprehensive and accurate evaluation of the cost between nodes, ensuring the selection of superior parent nodes. Additionally, a node expansion algorithm guided by repulsive fields is implemented, allowing for variable step-size node expansion. Finally, a path smoothing algorithm based on Bézier curves is applied to refine the final path, ensuring smoother and more efficient trajectories. The principles of the enhanced algorithm are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Sampling method optimization

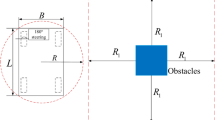

In the RRT*-Connect algorithm, random sampling is typically employed to generate sampling points across the entire workspace. However, this random sampling approach presents several issues, including an abundance of discrete sampling points and a lack of clear search direction, leading to decreased path search efficiency. To address these challenges, this study introduces an innovative target bias sampling algorithm. In this algorithm, the target point is selected with a specified probability during the generation of random sampling points27. This approach allows new nodes to expand towards the target point along straight lines, significantly enhancing the likelihood of discovering the shortest path. To manage sampling efficiency, the generation of random points is confined within an ellipsoidal space28. This ellipsoidal space features two focal points corresponding to the starting and target points. By effectively scaling the sampling space, the sampling efficiency and quality of path planning can be further optimized. The schematic diagram illustrating the improved sampling method is presented in Fig. 2.

The setting of the ellipsoidal sampling space in the figure takes into account the distance and direction between the two points, as well as the sampling range you want to control. Taking the ellipse space in the two-dimensional plane in the figure as an example, a common way to set the ellipse sampling space is to use the two points as the two focal points of the ellipse, and set the length of the ellipse’s major axis and minor axis to control the shape and size of the sampling space. Assuming that the start point is Xstart (xa, ya), the target point is Xgoal (xb, yb), the distance between the two points is d, the length of the major axis L is 3d, and the length of the minor axis W is 0.8d, then the semi-major axis a = 1.5d, the semi-minor axis b = 0.4d, and the ellipse is the length of the main axis. The distance is:

Sampling inside the ellipse generates Angle θ and radius r at random in polar coordinates, where 0 ≤ θ < 2π, 0 ≤ r ≤ 1. Convert polar coordinates to cartesian coordinates to obtain the coordinates of the sampling point (x, y) :

Pseudocode for‘Ellipsoidal space limits sampling points’is given in Algorithm 1.

The basic principle of the proposed target bias sampling algorithm is as follows: before sampling the random tree, random probability P in the range of [0 1] is introduced, and an adaptive threshold function Pa is introduced. Before each sampling, the probability value P is compared with the threshold function. If P is less than Pa, it indicates that the target point can be used as a random point for node expansion; if P is greater than Pa, it indicates that the original random sampling function is used for sampling. The random probability value P is essentially used to determine whether the current sampling point is sampled in the direction of the target point or in a specified random space. By generating a new probability value P each time, the algorithm can have certain randomness and diversity in the search process, which helps to avoid the local optimal solution, so as to better explore the whole search space.

Pseudocode for‘Target bias strategy’is given in Algorithm 2.

The mathematical expression for this process is as follows:

The proposed approach integrates the Linear Descending Inertia Weight (LDIW) and Adaptive Inertia Weight (AIW) strategies. The integration utilizes the advantages of LDIW to enhance global search and accelerate convergence29. The integration leverages the advantages of AIW to enable dynamic weight adjustment in response to environmental feedback30. The combination enables efficient global search while adapting to varying datasets and environmental changes. The combined method enhances overall efficiency through dynamic adjustment and adaptability.

LDIW is represented by the equation (depicted by Eq. (4))

AIW is represented by the equation (depicted by Eq. (5))

The adaptive threshold function Pa in Formula can be obtained by formula (6) :

Where, Pmax and Pmin are the maximum and minimum probability values respectively. In this article, Pmax = 0.9 and Pmin = 0.4 will be set. MAXitr means the maximum number of iterations, and Itr means the current number of iterations. The calculation formula of PS is shown in Eq. (7) :

Where N is the total random points currently generated, SSi is used to record whether the generated random node collides with obstacles. The mathematical expression of SSi is as follows:

According to Eq. (7), PS represents the proportion of random points that can successfully grow new nodes in all generated random points in each iteration. In this way, the quality of generated random points is quantified and the threshold function is dynamically adjusted. In addition, formula (6) will adaptively increase during the growth of random trees, so the closer the tree is to the target point, the easier it is to take the target point as the sampling point, which can also improve the search efficiency of the algorithm and avoid the local optimal solution. From the above formula, it can be seen that the adaptive threshold function can dynamically adjust the probability value of target bias according to the distance between the sampling point and the obstacle.

Cost function optimization

For the operation of parent node re-selection and path re-optimization, the original RRT*-Connect algorithm uses the path cost function defined as the Euclidean distances of each path to judge whether the new path is superior. This evaluation method is a simple and intuitive, performing well in straightforward scenarios. However, solely using the Euclidean distance sum evaluation method does not fully consider obstacle interaction and path complexity, This may cause the generated path to be excessively biased towards straight lines, ignoring environmental obstacles, and resulting in suboptimal paths31.

To address this, this article proposes an improved cost function that further evaluates the path cost by considering the area around the parent node and the obstacle cross area. This enhanced cost function better guides tree growth and path planning by considering the interaction between the path and environmental obstacles, thus more comprehensively measuring path feasibility and safety. The improved cost function effectively prevent the generated path from colliding or interfering with obstacles, making the search process more efficient. The improved cost function is shown in Fig. 3.

Node 8 in the figure is the target node for the parent operation of new node 9. The cost function obtained in the RRT*-Connect algorithm should be the sum of distances of all paths on the path 0–1-5–8-9. In the improved evaluation function, the cross area between the target node and the obstacle will be increased in the cost function on this basis. Take node 8 as an example, with its coordinates as the center of the circle, set within a radius to calculate the sum of the areas of obstacles contained within the range, that is, the filled area in the red circle in the figure. The new cost function is based on the original cost function plus the sum of the areas of all the filled regions. Accordingly, the new path cost function C(X) can be obtained by the following formula:

Where C(X) is the path cost of node X, C(Xparent) is the path cost of parent Xparent, and d(Xparent, X) is the Euclidean distance between parent Xparent and node X. Intersection (Xparent, X) is a function used to calculate the cross area of a circle drawn with the parent Xparent as the center of the circle and warea as the radius. The new cost function introduces a parameter warea, which is used to balance the weight of Euclidean distance and obstacle cross area in the path cost. By adjusting the value of warea, we can control how much attention the algorithm pays to obstacle avoidance in the course of path planning. When the warea is large, the algorithm is more inclined to select nodes with small cross area between the path and the obstacle, so as to avoid too many paths intersecting with the obstacle, and thus improve the quality of the path and the obstacle avoidance ability.

Pseudocode for‘Path Planning with Cost Calculation’is given in Algorithm 3.

Optimization of node expansion algorithm

In the RRT*-Connect algorithm, the choice of step size significantly affects the growth behavior of RRT* trees. A smaller step size generates a smooth path with dense waypoints, but it may cause the tree to inadequately fill the space. To fully explore unsearched space, a smaller step size needs to generate more nodes, thus increasing the execution time. On the other hand, setting a larger step size helps the tree branch converge to the target faster. This rough path with potential singularities can degrade the manipulator’s path tracking performance. In theory, when the number of nodes approaches infinity, any step size can solve the problem and achieve path exploration. However, in practice, number of vertices is limited, so the research focus should be placed on determining the adaptive strategy of variable step size32.

To achieve step size adaptability, Artificial Potential Field (APF) gradient descent strategy can adjust the step size. An artificial potential field represents environmental information based on the position and shape of obstacles, introducing attractive and repulsive forces. Obstacles create repulsive effect on the potential function, while the target region has has an attractive effect. By calculating the gradient of the potential energy function, nodes can be guided along direction of the potential energy reduction, enabling adaptive step size adjustment. The working principle of the adaptive step size algorithm is shown in Fig. 4.

The specific design steps are as follows:

1) Define a potential function: First, you need to define a potential function that represents information about obstacles in the environment and the location of the target area. The form of the potential function will be selected, usually the obstacle will have a negative effect on the potential function, while the target region will have a positive effect on the potential function. The potential energy function U contains the gravitational field function Uattract and the repulsive field function Urepulsion, and the potential energy function is expressed as Eq. (10) and Eq. (11).

Where ka and kr represent the gain factor of the gravitational field generated by the target point and the gain factor of the repulsive field generated by the obstacle respectively, the influence of the gravitational field and the repulsive field can be changed by adjusting these two parameters. dgoal(Xnear) and d(Xnear) represent the Euclidean distance respectively. d* represents the maximum safe distance between the node and the center point of the obstacle, that is, the collision space shown in Fig. 4. In the collision space, the repulsive force field will act and adjust the step size adaptively, while when the node is outside the safe distance, it will grow at the normal step size.

2) Calculate potential energy gradient: In the node expansion process of RRT*-Connect algorithm, the potential energy function can be used to calculate the gradient of the newly generated node to obtain the potential field generating force. The gradient can be regarded as the force, indicating that at the current position, the direction of the potential energy reduction should be advanced, and the advance length of the node can be adjusted according to the size and direction of the gradient.

Pseudocode for‘Node Expansion’is given in Algorithm 4.

The expression of the gravitational and repulsive values is as follows:

3) Adjust the step size according to the gradient: the step size of the current node can be adjusted adaptively according to the calculated potential energy gradient. In the unfavorable region, the potential function gradient is large, so the step size can be reduced to carefully avoid singularity and obstacles. In the open area, the gradient of the potential energy function is small, and the step size can be increased to speed up space exploration. The expression for calculating the adaptive step size S in different regions is as follows:

Where s represents a fixed step length at a safe distance, and scalar values are taken for both Fattract and Frepulsion.

Final path optimization

In this study, Bézier curves will be used to smooth the paths generated by the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm. A Bézier curve is a mathematical curve defined by a set of control points, known for its smooth interpolation between these points. Bézier curves possess the capability to adjust the weighting of control points, enabling a closer fit to specific requirements in crucial areas of the path. Additionally, they facilitate local path reconstruction without compromising the overall trajectory, thereby offering excellent controllability for path tracking and obstacle avoidance.

When using Bézier curve to smooth the path, we first need to select a set of critical path points from the path generated by the improved algorithm as the control points of the Bézier curve, which will determine the shape and direction of the curve. Control points on the curve represents the order of the Bezier curve, and the curve of the polynomial of degree N indicates that there are N + 1 control points on the curve. The mathematical expression is as follows:

Where Pi represents the position information of the i th control point in space, and Bni(t) represents the Bernstein-based function, which controls the curve shape by adjusting the weights of each control point. Each control point has a corresponding Bernstein-based function, which determines the curvature and smoothness of the curve in each part through interpolation and superposition, and its calculation formula is as follows:

In view of the characteristics of Bézier curve in local optimization, this study aims to further improve the smoothness and controllability by optimizing the path. Therefore, the third order Bézier curve is used to optimize the path segment composed of every four adjacent nodes on the path. In this segmented way, the shape of the path can be adjusted more finely, so that the local path quality can be further improved while maintaining the overall characteristics of the path. The segmented Bézier curve optimization can optimize the local details on the basis of preserving the overall trend of the path, thus improving the smoothness and controllability of the path. The parametric equation of the third-order Bézier curve is defined as follows:

Pseudocode for‘Final Path Optimization’is given in Algorithm 4.

The effect of the segmented Bézier curve optimization is shown in Fig. 5, from which the smooth change of the path can be clearly observed. Through the above segmented Bézier curve optimization strategy, finer adjustment can be achieved on each small segment of the path, so as to obtain smoother and more in line with the actual demand of the path planning results.

Theoretical analysis of time and space complexity

Time complexity analysis

The time complexity of the original Rapidly-exploring Random Tree Star Connect (RRT*-Connect) algorithm is primarily determined by four key stages. The sampling stage involves the random generation of points, which has a time complexity of \(\:O\left(n\right)\), where nn is the number of sampled points. The nearest neighbor search stage identifies the closest node to the sampled point, typically using a k-dimensional (K-D) tree, resulting in a time complexity of \(\:O\left(\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\). The tree expansion stage involves adding new nodes to the tree and updating path costs, with a complexity of \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\). Finally, the reconnection optimization stage re-evaluates and reconnects nearby nodes to optimize the path, also having a time complexity of \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\). Combining these stages, the overall time complexity of the original algorithm is \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\). The proposed improvements introduce several modifications that affect the time complexity. Target-biased sampling increases the probability of sampling near the goal, reducing unnecessary random sampling but requiring an additional probability computation step, resulting in a time complexity of \(\:O\left(n\right)\). Elliptical space sampling limits the sampling area to a specific elliptical region, which reduces the search space but introduces negligible computational cost at \(\:O\left(1\right)\). The cost function optimization enhances path quality by incorporating obstacle intersection area calculations, increasing the complexity of this step from \(\:O\left(\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\) to \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\). Additionally, the variable step-size expansion mechanism dynamically adjusts the step size using gradient-based potential fields, which introduces iterative computations with a time complexity of \(\:O\left(k\right)\), where kk is the number of gradient descent iterations. Overall, the improved algorithm maintains the asymptotic time complexity of \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\), though with an increase in constant factors due to these additional computations. Nevertheless, these optimizations result in a significant reduction in average runtime in practical scenarios.

Space Complexity Analysis

The space complexity of the original Rapidly-exploring Random Tree Star Connect (RRT*-Connect) algorithm is influenced by two main factors. First, the storage of all nodes in the tree, including their positions and connections, has a space complexity of \(\:O\left(n\right)\), where nn is the total number of nodes. Second, auxiliary data structures, such as a k-dimensional (K-D) tree used for nearest neighbor searches, also require a space complexity of \(\:O\left(n\right)\). The proposed improvements introduce additional storage requirements to accommodate the new functionalities. Target-biased sampling necessitates storing parameters related to sampling probabilities and elliptical regions, which adds a fixed storage cost of \(\:O\left(1\right)\). The cost function optimization requires storing intermediate results for obstacle intersection area calculations, which increases the storage complexity by \(\:O\left(m\right)\), where mm is the number of obstacles in the environment. Furthermore, the variable step-size expansion mechanism involves storing gradient information for dynamic step-size adjustments, contributing an additional fixed cost of \(\:O\left(1\right)\). Despite these additional requirements, the overall space complexity of the improved algorithm remains \(\:O\left(n\right)\), with only minor increases in constant factors due to the inclusion of these new parameters.

Summary

The improved Rapidly-exploring Random Tree Star Connect (RRT*-Connect) algorithm retains the theoretical time complexity of \(\:O\left(n\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}n\right)\) and space complexity of \(\:O\left(n\right)\) associated with the original algorithm. However, the proposed modifications, including target-biased sampling, elliptical space constraints, cost function optimization, and variable step-size expansion, introduce enhancements that optimize the sampling, expansion, and cost evaluation processes. While these improvements slightly increase the computational overhead in terms of constant factors, they significantly reduce the average runtime and improve the overall path quality in practical applications. As a result, the enhanced algorithm is better suited for solving complex path planning problems in high-dimensional environments with intricate obstacle configurations.

Simulation and discussion

Two-dimensional space simulation

In this section, we’ll compare the performance of the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm with three other algorithms: the basic RRT algorithm, RRT* algorithm, and RRT*-Connect algorithm. We’ll evaluate each algorithm in various two-dimensional environments and three-dimensional spaces, analyzing differences in indicators like the number of iterations, path length, and running time. The goal is to demonstrate how the improved algorithm performs in different scenarios. These simulation experiments will be conducted using MATLAB R2020b on a Windows 10 64-bit operating system, with an Intel Core i7-7700HQ CPU @ 2.80 GHz and 8.00GB of RAM.

In order to verify the adaptability and effectiveness of the improved algorithm, four different obstacle environments, namely general obstacle distribution environment, narrow environment, multi-obstacle environment and labyrinth environment, are set up in a two-dimensional plane to simulate each algorithm. The two-dimensional space is set to 1000 × 1000, the start point of the path is set to (100, 100), the target point is set to (900, 900), the fixed step size used in each algorithm is set to 15, and the maximum number of iterations of the algorithm is set to 4000. The simulated paths obtained by each algorithm in different environments are shown in Fig. 6.。.

In Fig. 6, obstacles are depicted as black rectangles, while paths generated by different algorithms are represented by various colored lines. The performance analysis across different environments is summarized as follows:

-

(1)

General Environment: Fig. 6 (b) shows a scenario with six rectangular obstacles, reflecting a relatively simple spatial layout. All algorithms produce similar paths, closely approximating the shortest route and meeting basic obstacle avoidance requirements.

(2) Narrow Environment: In a narrow environment with two 10-unit-long channels (Fig. 6 (b)), the RRT algorithm, limited by random sampling and path refinement, fails to find shorter paths in narrow spaces. In contrast, the other three algorithms efficiently plan superior paths, successfully navigating the narrow channels. The improved RRT*-Connect algorithm stands out with smoother paths and improved safety margins at turning points due to its adaptive step expansion and node rewriting strategy.

(3) Multi-Obstacle Environment: Fig. 6 (c) displays an environment with numerous obstacles, posing a challenging obstacle avoidance scenario. RRT and RRT* algorithms, constrained by unidirectional growth, may not generate optimal paths. The bidirectional growth of the RRT*-Connect algorithm and its enhanced version excel in multi-obstacle environments, providing flexibility and comprehensive exploration capabilities, increasing the likelihood of finding near-optimal paths.

(4) Labyrinth Environment: Fig. 6 (d) presents a labyrinthine environment with narrow passages and dense obstacles. The improved RRT*-Connect algorithm effectively shortens path lengths by crafting paths aligned with maze walls. It achieves this through adaptive step expansion and node rewriting, ensuring smooth, collision-free paths. Other algorithms may introduce unnecessary twists and turns during path planning due to limitations in node expansion, reducing path optimization.

In Fig. 7, paths generated by different algorithms illustrate their performance in various environments. To assess and compare these algorithms more precisely, we conducted detailed analysesfocusing on key parameters like iterations, path length, and runtime. The optimized RRT*-Connect algorithm and three others were simulated in the four environments, each undergoing 100 simulations. Data from these simulations are depicted in Fig. 7, with the following observations for these algorithms:

-

(1)

Iterations: In Fig. 7(a), the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm consistently requires significantly fewer iterations across all environments. For instance, in the general environment, it averages 373 iterations, whereas other algorithms fluctuate between 500 and 1000 iterations. Note that in narrow environments, the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm’s iteration count is slightly higher, attributed to its adaptive step size, which adjusts in tight spaces, slowing tree expansion.

-

(2)

Runtime: Fig. 7(b) shows the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm’s relatively short runtime in various environments. However, the gap narrows in general environments due to simpler obstacle layouts. In maze-like settings, the improved algorithm reduces runtime by up to 46% compared to the shortest among the other three algorithms, RRT*-Connect.

(3) Path Length: As seen in Fig. 7(c), the improved algorithm consistently generates the shortest paths in diverse environments. Its minimal path standard deviation indicates its ability to consistently produce near-optimal paths in various settings. This performance stems from the introduction of gravitational and repulsive fields, enhancing node expansion. Gravitational fields guide the search towards the target, while repulsive fields prevent collisions, making the improved RRT*-Connect more likely to find the shortest path, improving algorithm robustness and stability.

(4) Number of Nodes: In path planning, fewer nodes typically indicate a more direct path. Figure 7(d) reveals a slightly higher average node count for the improved algorithm in maze environments due to its adaptive node expansion strategy, which requires additional circumnavigation to avoid obstacles in maze corners.

Three-dimensional space simulation

As shown in Fig. 7, in a low-complexity environment, the performance of the algorithms is not significantly different. To make the performance comparison more intuitive, simulation tests were conducted on the four algorithms in a three-dimensional space. The three-dimensional space is set to 1000 × 1000 × 1000, the starting point of the path is set to (100, 100, 100), the target point is set to (900, 900, 900), the maximum number of iterations is 8000, and 15 rectangular obstacles of different sizes are placed in the space. Each algorithm conducted 50 simulation experiments. The simulation path comparison of each algorithm in a three-dimensional environment is shown in Fig. 8, and the algorithm comparison results are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Fig. 8, the search and final paths generated by each algorithm for obstacle avoidance path planning in a three-dimensional environment are displayed. The search path starting from the starting point is represented by the blue curve, the search path starting from the target point is represented by the orange curve, and the final optimal path is represented by the red curve. Table 1 successively shows the iteration times N, running time T, path length L, number of nodes P and planning success rate of each algorithm after obstacle avoidance path planning in three-dimensional space, where µ and σ respectively represent the mean and standard deviation of each data.

Table 1 highlights significant differences in iteration counts and runtime, particularly in complex three-dimensional environments. The Traditional RRT algorithm (Fig. 8a) falls behind other algorithms, generating widely distributed and dense search paths, reducing search efficiency. Its average path length of 1872 exceeds the shortest path by 19.55%, occasionally resulting in planning failures, especially in complex 3D settings. The RRT* algorithm (Fig. 8b) improves search efficiency and reduces runtime by altering node distribution but still produces dense search paths after rerouting, resulting in a path length of 1795. Both RRT and RRT* exhibit high randomness, with path length standard deviations of 130.99 and 133.01, and occasional planning failures, indicating a need for stability improvements. The RRT*-Connect algorithm (Fig. 8c), with its bidirectional search strategy, significantly enhances performance. It generates concentrated search paths, efficiently explores three-dimensional space, maintains planning success, and results in a shorter optimal path than RRT and RRT*.In Fig. 8d, the improved algorithm surpasses RRT*-Connect, generating concise and smoother search paths. It outperforms other algorithms with an average path length of 1506 and a low standard deviation of 100.51, demonstrating stability and efficiency in three-dimensional environments.

Experiment

To verify whether the improved algorithm can realizeobstacle avoidance path planning in a real environment, this chapter designs an obstacle avoidance grasping system for a three-degree of freedom robotic arm based on a binocular camera for visual positioning. The experimental platform and the hardware equipment used are shown in Fig. 9. The experimental platform consists offour main parts: a host computer, a manipulator controller, a manipulator and a binocular camera. The binocular camera identifies the environment and locates the obstacles. After obtaining the obstacle coordinates, the host computer runs the path planning algorithm to plan the optimal path. The algorithm model obtained by the host computer is compiled by the manipulator controller to control the manipulator to grasp and move the object. The captured object used in the experiment is shown in Fig. 9 (f). The end effector used for grasping is a single-port flexible suction cup. The object is captured by negative pressure adsorption and transported to the placing platform shown in Fig. 9 (g).

Using the obstacle information obtained from MATLAB software, a complete robotic arm model was constructed in the simulation environment. After configuring the simulation environment of the experimental platform, the improved algorithm generated the obstacle avoidance path, The robotic arm then moved from the starting point to the coordinate position of the captured object. After successfully capturing the target, the obstacle avoidance plan was carried out, and the robotic arm \moved to the specified position. Figure 10 shows the obstacle avoidance path in the simulation environment.

The process of obstacle avoidance movement of the mechanical arm in an environment with obstacles is shown in Fig. 11. In the figure, after successfully grasping the target object, the robotic arm first lifts the target object vertically. At this time, there are obstacles near the target object and the connecting rod at the end of the robotic arm. To avoid these obstacles, the robotic arm lifts the captured object to a higher position and then moves towards the target point. During the movement, the object is kept at a safe distance from the obstacles to avoid collisions. When the robotic arm passes over an obstacle, it moves downward vertically while moving horizontally to shorten the path length. This continues until the robotic arm successfully avoids the obstacle and reaches the target position. Finally, the robotic arm places the captured object, marking the completion of the obstacle avoidance path planning.

In conclusion, the improved algorithm and the other three algorithms mentioned above were used in the robotic arm experiment. Each algorithm conducted 20 path planning experiments, and the results are shown in Table 2. As can be seen from the table, in terms of the number of algorithm iterations and average planning time, the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm performed excellently. It was significantly better than the traditional RRT algorithm, showing an improvement of 41.49%. Compared to the standard RRT*-Connect algorithm, the improvement was 19.39%.

Additionally, the average path length generated by the improved algorithm was shorter by 11.86%, 4.29%, and 5.2% compared to other algorithms. No collisions occurred during the experiments, verifying that the improved RRT*-Connect algorithm has enhanced performance over the original algorithm and meets the obstacle avoidance planning needs of the robotic arm in experimental motion.

Generalizability and future applications

The modular design of the proposed RRT*-Connect algorithm, incorporating features such as target-biased sampling, variable step-size expansion, and an enhanced cost function, makes it adaptable to a wide range of robotic systems. Beyond the three-degree-of-freedom robotic arm used in this study, the algorithm can potentially be extended to six-degree-of-freedom industrial manipulators or even mobile robotic platforms, addressing diverse path planning challenges.

The integration of elliptical space sampling and repulsive potential fields demonstrates robustness in environments with dense or irregularly shaped obstacles. These features suggest that the algorithm could perform effectively in highly complex scenarios, such as maze-like structures or configurations with numerous dynamic obstacles.

Additionally, the algorithm’s modularity enables potential applications in dynamic environments and multi-robot systems. For instance, incorporating real-time sensor data could allow for adaptive updates to planned paths in response to moving obstacles. In multi-robot systems, the algorithm could be used to optimize collaborative path planning, minimizing the risk of collision while improving overall efficiency.

Future improvements may involve integrating machine learning-based modules to enhance adaptability and leveraging predictive models for better handling of highly dynamic scenarios. Real-world testing on high-degree-of-freedom robotic arms, mobile robots, and complex industrial environments will further validate and expand the algorithm’s applicability.

Conclusion

This article focuses on optimizing the obstacle avoidance path planning algorithm for a robotic arm, building upon the RRT*-Connect algorithm. After identifying deficiencies in existing algorithms, a series of optimization strategies are proposed to address these issues. These strategies include introducing the target bias algorithm and elliptic space sampling to improve the sampling process, using the cross area between parent nodes and obstacles to refine the cost function for evaluating path cost, and implementing an adaptive step size by artificial potential field and gradient descent strategy to enhance node expansion. Finally, a piecewise Bezier curve is used to smooth the final path and ensure stability.

Subsequently, simulation experiments are conducted to validate each algorithm using MATLAB software. Initially, four different environments are set up in a two-dimensional plane, and algorithm performance is analyzed by comparing various algorithms. These results are then extended to three-dimensional space simulations, evaluating performance indices such as average iteration count, runtime, path length, and number of nodes on the final path. The findings indicate that the improved algorithm achieves an average runtime of only 5.01 s in three-dimensional space, with a path length of 1506. This demonstrates that the improved algorithm effectively meets the requirement of finding optimal obstacle avoidance paths and boasts significant performance advantages.

To further validate the performance of the proposed improved RRT*-Connect algorithm in practical applications, we constructed a three-degree-of-freedom robotic arm obstacle-avoiding grasping system experiment platform. This platform utilizes a binocular camera for visual positioning. We then conducted a robotic arm obstacle-avoiding motion planning experiment using the improved algorithm. In order to thoroughly test the algorithm, we also conducted 20 obstacle avoidance tests for each algorithm. Through a comparative analysis of the experimental results, we confirmed that the improved algorithm outperforms the original algorithm, meeting the requirements for robotic arm obstacle avoidance planning.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cheng, X. et al. An improved RRT-Connect path planning algorithm of robotic arm for automatic sampling of exhaust emission detection in industry 4.0. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 33 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jii.2023.100436 (2023).

Luan, P. G. & Thinh, N. T. Hybrid genetic algorithm based smooth global-path planning for a mobile robot. Mech. Based Des. Struc. 513, 1758–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2021.1876569 (2023).

Lin, S. W., Liu, A., Wang, J. G. & Kong, X. Y. An intelligence-based hybrid PSO-SA for mobile robot path planning in warehouse. J. Comput. Sci-Neth. 67 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2022.101938 (2023).

Loganathan, A. & Ahmad, N. S. A systematic review on recent advances in autonomous mobile robot navigation. Eng. Sci. Technol. 40 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2023.101343 (2023).

Jeong, I. B., Lee, S. J. & Kim, J. H. Quick-RRT*: triangular inequality-based implementation of RRT* with improved initial solution and convergence rate. Expert Syst. Appl. 123, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.01.032 (2019).

Noh, G., Park, J., Han, D. & Lee, D. Selective goal aiming rapidly exploring Random Tree path planning for UAVs. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space. 226, 1397–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42405-021-00406-7 (2021).

Kiani, F. et al. Adapted-RRT: novel hybrid method to solve three-dimensional path planning problem using sampling and metaheuristic-based algorithms. Neural Comput. Appl. 3322, 15569–15599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06179-0 (2021).

Gültekin, A., Diri, S. & Becerikli, Y. Simplified and smoothed rapidly-exploring Random Tree Algorithm for Robot path planning. Vjesn. 303, 891–898. https://doi.org/10.17559/tv-20221015080721 (2023).

Eshtehardian, S. A. & Khodaygan, S. A continuous RRT*-based path planning method for non-holonomic mobile robots using B-spline curves. J. Amb Intel Hum. Comp. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-021-03625-8 (2022).

Schmid, L. et al. An efficient sampling-based method for online informative path planning in unknown environments. Ieee Robot Autom. Let. 52, 1500–1507. https://doi.org/10.1109/lra.2020.2969191 (2020).

Arab, F., Shirazi, F. A. & Yazdi, M. R. H. Planning and distributed control for cooperative transportation of a non-uniform slung-load by multiple quadrotors. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 117 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2021.106917 (2021).

Mohammed, H., Romdhane, L. & Jaradat, M. A. RRT*N: an efficient approach to path planning in 3D for static and dynamic environments. Adv. Rob. 353-4, 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01691864.2020.1850349 (2021).

Ma, G. J., Duan, Y. L., Li, M. Z., Xie, Z. B. & Zhu, J. A probability smoothing Bi-RRT path planning algorithm for indoor robot. Future Gener Comp. Sy. 143, 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2023.02.004 (2023).

Nazarahari, M., Khanmirza, E. & Doostie, S. Multi-objective multi-robot path planning in continuous environment using an enhanced genetic algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 115, 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2018.08.008 (2019).

Qi, J., Yang, H. & Sun, H. X. A sampling-based algorithm for Robot path planning in dynamic environment. Ieee T Ind. Electron. 688, 7244–7251. https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2020.2998740 (2021).

Liu, L. X. et al. Path planning techniques for mobile robots: review and prospect. Expert Syst. Appl. 227 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120254 (2023).

Qadir, Z., Ullah, F., Munawar, H. S. & Al-Turjman, F. Addressing disasters in smart cities through UAVs path planning and 5G communications: a systematic review. Comput. Commun. 168, 114–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2021.01.003 (2021).

Kumar, B. P., Hariharan, K. & Manikandan, M. S. K. Hybrid long short-term memory deep learning model and Dijkstra’s Algorithm for fastest travel route recommendation considering eco-routing factors. Transp. Lett. 158, 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/19427867.2022.2113273 (2023).

Kang, M. et al. A RRT based path planning scheme for multi-DOF robots in unstructured environments. Comput. Electron. Agr. 218 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108707 (2024).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Model-based safe reinforcement learning with time-varying constraints: applications to Intelligent vehicles. Ieee T Ind. Electron. https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2023.3317853 (2024).

Dudeja, C. & Kumar, P. An improved weighted sum-fuzzy Dijkstra’s algorithm for shortest path problem (iWSFDA). Soft Comput. 267, 3217–3226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-06871-w (2022).

Kang, N. K., Son, H. J. & Lee, S. H. Modified A-star algorithm for modular plant land transportation. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 3212, 5563–5571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-018-1102-z (2018).

Kurosawa, K., Uchiyama, Y. & Kosako, T. Development of a numerical marine weather routing system for coastal and marginal seas using regional oceanic and atmospheric simulations. Ocean. Eng. 195 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106706 (2020).

Ding, J. et al. An improved RRT* algorithm for robot path planning based on path expansion heuristic sampling. J. Comput. Sci-Neth. 67 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2022.101937 (2023).

Przybylski, M. Asymptotically optimal A* for Kinodynamic Planning. Ieee Robot Autom. Let. 95, 4353–4360. https://doi.org/10.1109/lra.2024.3379847 (2024).

Kashyap, A. K., Parhi, D. R., Muni, M. K. & Pandey, K. K. A hybrid technique for path planning of humanoid robot NAO in static and dynamic terrains. Appl. Soft Comput. 96 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106581 (2020).

Xiao, G. Z. et al. NA-OR: A path optimization method for manipulators via node attraction and obstacle repulsion, Sci. China. Technol. Sc. 665 1205–1213, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11431-022-2238-1

Qi, J. Y. et al. Path planning and collision avoidance based on the RRT*FN framework for a robotic manipulator in various scenarios. Complex. Intell. Syst. 96, 7475–7494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-023-01131-2 (2023).

Huang, X. W., Li, C. P., Chen, H. F. & An, D. Task scheduling in cloud computing using particle swarm optimization with time varying inertia weight strategies. Cluster Computing-the J. Networks Softw. Tools Appl. 232, 1137–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-019-02983-5 (2020).

Nickabadi, A., Ebadzadeh, M. M. & Safabakhsh, R. A novel particle swarm optimization algorithm with adaptive inertia weight. Appl. Soft Comput. 114, 3658–3670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2011.01.037 (2011).

Shen, H. H., Xie, W. F., Tang, J. Y. & Zhou, T. Adaptive manipulability-based path planning strategy for Industrial Robot manipulators. Ieee-Asme T Mech. 283, 1742–1753. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmech.2022.3231467 (2023).

Yi, J. H., Yuan, Q. N., Sun, R. T. & Bai, H. Path planning of a manipulator based on an improved P_RRT* algorithm. Complex. Intell. Syst. 83, 2227–2245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-021-00628-y (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Miaolong Cao: Conceptualized the research problem, supervised the overall writing process, and contributed to the manuscript revisions.Huawei Mao: Led the writing and revision of the manuscript, created figures and charts, and assisted with overall article revision.Xiaohui Tang: Collected the data.Yuzhou Sun: Analyzed the data.Tiandong Cheng: Provided feedback and reviewed the manuscript.All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, M., Mao, H., Tang, X. et al. A novel RRT*-Connect algorithm for path planning on robotic arm collision avoidance. Sci Rep 15, 2836 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87113-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87113-5