Abstract

Malnutrition and PM2.5 pollution remain a pressing global public health concern, especially to vulnerable populations like children under five years old. This study aimed to investigate the correlation between undernutrition in children under five years old and air pollution (exposure to PM2.5) on a global scale. This ecological study evaluated the correlation between undernutrition (wasting and stunting) and air pollution in 123 countries. A multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify the factors significantly related to the wasting and stunting. The scatter plots were utilized to depict the prevalence of wasting and stunting in children under five years old across studied countries concerning air pollution, Human Development Index (HDI), and Socio-Demographic Index (SDI). The prevalence of wasting was higher in countries with higher exposure to PM2.5 (R2 = 0.13, p < 0.001), less HDI (R2 = 0.20, p < 0.001), and less SDI (R2 = 0.16, p = 0.005). Also, the prevalence of stunting was higher in countries with higher exposure to PM2.5 (R2 = 0.07, p = 0.003), less HDI (R2 = 0.54, p < 0.003), and less SDI (R2 = 0.52, p = 0.005). The results of multivariable linear regression indicated a direct and positive correlation between the prevalence of wasting in children under five years old and exposure to PM2.5 (β = 0.06, p = 0.003) and an indirect and negative correlation with HDI (β =-10.3, p < 0.001). Also, there was a significant association between the prevalence of stunting and HDI (β =-44, p < 0.003). There was a significant relationship between the prevalence of wasting in children under five years old and exposure to PM2.5 and HDI. Further research is required to confirm this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition presents a significant public health challenge for children worldwide1 with approximately half of all deaths in children under five years old attributed to malnutrition2. Eliminating malnutrition could potentially reduce the global disease burden by around 32%3. Undernutrition is a type of malnutrition, which includes stunting, wasting, and underweight4. Wasting usually indicates recent substantial weight loss, although it can persist for a prolonged period4. In 2020, the global prevalence of wasting in children under five years old of age was estimated at 45.4 million, with 13.6 million experiencing severe wasting5. Moreover, in 2016 the worldwide prevalence of stunting in children under five years old was 22.9%6.

In children, wasting is linked to an increased risk of mortality without proper intervention4, and can result in permanent outcomes such as impaired cognitive function, decreased muscle mass, stunted growth in adulthood, reduced efficiency, and lower income potential5,7. Also, Stunting can significantly and permanently affect a child’s physical and cognitive growth2.

In many countries, the population-weighted annual exposure to ambient particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) has increased over the last decade8. PM2.5 is present everywhere and is becoming increasingly prevalent in all kinds of environments, particularly in rapidly expanding urban areas9.

PM2.5 poses a significant environmental health concern due to its potential adverse effects on human health, especially for vulnerable groups such as children10. PM2.5 exposure has been linked with various health problems, including heart diseases, premature births, and other medical conditions10. Also, PM2.5 can favor the onset of respiratory and neurodegenerative diseases11,12,13. However, only a few studies have assessed the association between air pollution and malnutrition14,15. One study across 32 African countries revealed that exposure to PM2.5 is a significant indicator of childhood undernutrition2. Also, most existing research has investigated the adverse effects of air pollution on children under five years old in Africa2,14,15. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the association between air pollution and undernutrition among children worldwide. Therefore, acknowledging the limitations of ecological studies, this study aimed to determine the correlation between undernutrition (wasting and stunting) in children under five years old and air pollution, worldwide.

Methods

Study design and data collection

Given the ecological nature of this survey, all variables analyzed are aggregate variables. In this study a compiled dataset was created to collect data from each country regarding undernutrition, air pollution, SDI and HDI. We collected the data on undernutrition and air pollution from the WHO website (https://www.who.int) until May 19, 202316. Also, the details about SDI data was obtained from the IHME website (https://ghdx.healthdata.org)17, while the data on HDI were collected from human development reports (https://hdr.undp.org)18.

PM2.5

In this study, air pollution was defined as exposure to annual exposure to ambient particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) according (µg/m3)19. In fact, the main exposure variable in the current study was ambient PM2.5 concentrations(µg/m3).

Wasting

Environmental factors account for a greater proportion of weight variation in children under five years old than ethnic disparities. Child wasting is a widely acknowledged indicator of child nutrition. Our model utilized the weight-for-length z-score for children under five years old as the outcome variable, a standardized measure of child weights commonly used to assess wasting. This z-score was determined by comparing the child’s measurements with the median value in the reference population of the National Centre for Health Statistics International Growth Reference. Wasting was defined as a weight-for-length z-score < -2 standard deviations from the median following the criteria by WHO Expert Committee on Physical Status: the Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry20. In the present study, the prevalence of wasting was defined as the percentage of children who exhibited wasting.

Stunting

Stunting is defined as a Height-for-Age Z-score (HAZ) of less than − 2 standard deviations from the median according to the WHO Expert Committee on Physical Status: the Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry20. In this study, the prevalence of stunting was determined as the percentage of children who displayed stunting.

HDI

The HDI is widely used to measure a country’s overall development and well-being, considering not only economic factors but also education and health outcomes. Comprising three key dimensions life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators the HDI integrates various aspects into a singular index, offering a comprehensive perspective on human development beyond mere economic parameters. This holistic approach enables policymakers and researchers to better understand the complex interplay among these different facets of well-being and to monitor progress effectively over time. The HDI ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher score reflecting greater overall development18.

SDI

The SDI is a composite index that measures the developmental status of a country or region based on per capita income, educational attainment, and fertility rates. It is expressed on a scale from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating the least developed state and 1 representing the most developed. SDI serves as a tool for country rankings based on their developmental levels17.

Statistical analysis

Scatter plots were generated to visualize the relationship of wasting and stunting in children under five years old in all countries with air pollution, HDI, and SDI. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to verify the correlation between undernutrition with air pollution, HDI, and SDI. Additionally, the R-squared (R2) value was calculated to quantify the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables in the sample, as indicated by R2 values ranging between 0 and 121.

Univariate linear regression was used to determine the association between the wasting and stunting in children under five years old and the study variables. Subsequently, variables with p-values less than 0.25 in the univariate linear regression were included into the multivariable linear regression model. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted after obtaining necessary agreements and approval from the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1402.1223).

Results

Wasting

This ecological study revealed that among all the countries surveyed, India (18.7%), Yemen (16.4%) and Sudan (16.3%) reported the highest prevalence of wasting while the United States (0.10%), South Korea (0.20%), and Chile (0.30%) respectively reported the lowest prevalence of wasting in children under five years old. Western Africa, Southern Asia, and Southeastern Asia have consistently shown a significant burden of wasting.

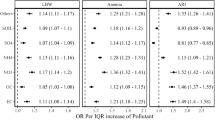

The univariate linear regression model for P.M2.5, HDI and SDI is presented in Table 1. The results showed a significant correlation between the prevalence of wasting in children under five years old and P.M2.5 (R2 = 0.13), HDI (R2 = 0.20), and SDI (R2 = 0.16).

In the next step, multivariable linear regression with a stepwise method was conducted to determine the variables correlated to the prevalence of wasting in children under five years old. Variables with p-values less than 0.25 in the univariate analysis were entered into the model. The results revealed a significant association between the prevalence of wasting and P.M2.5 (β = 0.06, p = 0.003) and HDI (β =-10.3, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

The scatter plots representing the prevalence of wasting in children under five years old in terms of P.M2.5, HDI, and SDI are shown in Fig. 1. The highest R2 was observed for HDI followed by SDI. Collinearity between the variables was also evaluated in this study revealing moderate collinearity between HDI and SDI (VIF = 6.3).

Scatter plot of correlation between prevalence of wasting in under five years old children and PM2.5, HDI, and SDI. (a) Afghanistan, ALB: Albania, DZA: Algeria, AGO: Angola, ARG: Argentina, ARM: Armenia, AZE: Azerbaijan, BGD: Bangladesh, BEL: Belgium, BLZ: Belize, BEN: Benin, BOL: Bolivia (Plurinational State of), BRA: Brazil, BGR: Bulgaria, BFA: Burkina Faso, BDI: Burundi, KHM: Cambodia, CMR: Cameroon, CAF: Central African Republic, TCD: Chad, CHL: Chile, CHN: China, COL: Colombia, COD: Congo, CRI: Costa Rica, CIV: Côte d’Ivoire, CUB: Cuba, KOR: North Korea, COD: Democratic Republic of the Cong, DJI: Djibouti, DOM: Dominican Republic, ECU: Ecuador, EGY: Egypt, SLV: El Salvador, EST: Estonia, SWZ: Eswatini, ETH: Ethiopia, FJI: Fiji, GAB: Gabon, GMB: Gambia, GEO: Georgia, DEU: Germany, GHA: Ghana, GTM: Guatemala, GIN: Guinea, GNB: Guinea-Bissau, GUY: Guyana, HTI: Haiti, HND: Honduras, IND: India, IDN: Indonesia, IRN: Iran (Islamic Republic of), IRQ: Iraq, JAM: Jamaica, JOR: Jordan, KAZ: Kazakhstan, KEN: Kenya, KIR: Kiribati, KWT: Kuwait, KGZ: Kyrgyzstan, LAO: Lao People’s Democratic Republic, LVA: Latvia, LBN: Lebanon, LSO: Lesotho, LBR: Liberia, LBY: Libya, LTU: Lithuania, MDG: Madagascar, MWI: Malawi, MYS: Malaysia, MDV: Maldives, MLI: Mali, MHL: Marshall Islands, MRT: Mauritania, MEX: Mexico, MNG: Mongolia, MNE: Montenegro, MAR: Morocco, MOZ: Mozambique, MMR: Myanmar, NAM: Namibia, NPL: Nepal, NER: Niger, NGA: Nigeria, MKD: North Macedonia, OMN: Oman, PAK: Pakistan, PAN: Panama, PRY: Paraguay, PER: Peru, PHL: Philippines, PRT: Portugal, PRK: South Korea, RWA: Rwanda, WSM: Samoa, STP: Sao Tome and Principe, SAU: Saudi Arabia, SEN: Senegal, SRB: Serbia, SLE: Sierra Leone, SLB: Solomon Islands, ZAF: South Africa, LKA: Sri Lanka, SDN: Sudan, SUR: Suriname, TJK: Tajikistan, THA: Thailand, TLS: Timor-Leste, TGO: Togo, TON: Tonga, TUN: Tunisia, TUR: Türkiye, TKM: Turkmenistan, UGA: Uganda, TZA: United Republic of Tanzania, USA: United States of America, URY: Uruguay, UZB: Uzbekistan, VUT: Vanuatu, VNM: Viet Nam, YEM: Yemen, ZMB: Zambia, ZWE: Zimbabwe. (b) All countries in (a). (c) All countries in (a).

Stunting

Worldwide, the prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years old in 2022 by countries is presented in Fig. 222. Burundi (56.5%), Libya (52.2%) and Niger (47.4%) respectively reported the highest prevalence of stunting, while Estonia (1.2%), Chile (1.6%), and South Korea (1.7%) respectively reported the lowest prevalence of stunting in children under five years old.

The univariate linear regression model for P.M2.5, HDI and SDI are presented in Table 3. The results showed a significant correlation between the prevalence of stunting in children under five years old and P.M2.5 (R2 = 0.07), HDI (R2 = 0.54), and SDI (R2 = 0.52).

In the following step, multivariable linear regression using a stepwise approach was used to identify the variables associated with the prevalence of stunting in children under five years old. The variables with p-values less than 0.25 in the univariate analysis were included into the model. The results revealed no significant association between the prevalence of stunting and P.M2.5 (β = 0.01, p = 0.79) and SDI (β =-23.3, p < 0.07), however, there was a significant association between the prevalence of stunting in children under five years old and HDI(β =-44, p < 0.003) (Table 4).

The scatter plots depicting the prevalence of stunting in children under five years old in terms of P.M2.5, HDI, and SDI are presented in Fig. 3. Notably, the highest R2 was observed for HDI followed by SDI.

Scatter plot of correlation between prevalence of stunting in under five years old children and PM2.5, HDI, and SDI. (a) Afghanistan, ALB: Albania, DZA: Algeria, AGO: Angola, ARG: Argentina, ARM: Armenia, AZE: Azerbaijan, BGD: Bangladesh, BEL: Belgium, BLZ: Belize, BEN: Benin, BOL: Bolivia (Plurinational State of), BRA: Brazil, BGR: Bulgaria, BFA: Burkina Faso, BDI: Burundi, KHM: Cambodia, CMR: Cameroon, CAF: Central African Republic, TCD: Chad, CHL: Chile, CHN: China, COL: Colombia, COD: Congo, CRI: Costa Rica, CIV: Côte d’Ivoire, CUB: Cuba, KOR: North Korea, COD: Democratic Republic of the Cong, DJI: Djibouti, DOM: Dominican Republic, ECU: Ecuador, EGY: Egypt, SLV: El Salvador, EST: Estonia, SWZ: Eswatini, ETH: Ethiopia, FJI: Fiji, GAB: Gabon, GMB: Gambia, GEO: Georgia, DEU: Germany, GHA: Ghana, GTM: Guatemala, GIN: Guinea, GNB: Guinea-Bissau, GUY: Guyana, HTI: Haiti, HND: Honduras, IND: India, IDN: Indonesia, IRN: Iran (Islamic Republic of), IRQ: Iraq, JAM: Jamaica, JOR: Jordan, KAZ: Kazakhstan, KEN: Kenya, KIR: Kiribati, KWT: Kuwait, KGZ: Kyrgyzstan, LAO: Lao People’s Democratic Republic, LVA: Latvia, LBN: Lebanon, LSO: Lesotho, LBR: Liberia, LBY: Libya, LTU: Lithuania, MDG: Madagascar, MWI: Malawi, MYS: Malaysia, MDV: Maldives, MLI: Mali, MHL: Marshall Islands, MRT: Mauritania, MEX: Mexico, MNG: Mongolia, MNE: Montenegro, MAR: Morocco, MOZ: Mozambique, MMR: Myanmar, NAM: Namibia, NPL: Nepal, NER: Niger, NGA: Nigeria, MKD: North Macedonia, OMN: Oman, PAK: Pakistan, PAN: Panama, PRY: Paraguay, PER: Peru, PHL: Philippines, PRT: Portugal, PRK: South Korea, RWA: Rwanda, WSM: Samoa, STP: Sao Tome and Principe, SAU: Saudi Arabia, SEN: Senegal, SRB: Serbia, SLE: Sierra Leone, SLB: Solomon Islands, ZAF: South Africa, LKA: Sri Lanka, SDN: Sudan, SUR: Suriname, TJK: Tajikistan, THA: Thailand, TLS: Timor-Leste, TGO: Togo, TON: Tonga, TUN: Tunisia, TUR: Türkiye, TKM: Turkmenistan, UGA: Uganda, TZA: United Republic of Tanzania, USA: United States of America, URY: Uruguay, UZB: Uzbekistan, VUT: Vanuatu, VNM: Viet Nam, YEM: Yemen, ZMB: Zambia, ZWE: Zimbabwe. (b) All countries in (a). (c) All countries in (a).

P.M2.5، HDI and SDI

The average annual population-weighted P.M2.5 concentration(µg/m3) in 2019 is presented in Fig. 423. Among all countries surveyed, the lowest values of P.M2.5 were reported in Estonia (6.6), America (7.4) and Marshall Islands (7.5), while the highest were reported in Afghanistan (75.2), Kuwait (67.2) and Egypt (64.1), respectively. The lowest HDI scores were observed in Chad (3.9), Central African Republic (4.0) and Burundi (4.3), while the highest HDI was observed China (0.95), Germany (0.94) and Belgium (0.94). Also, the lowest SDI was reported in Niger (0.16), Chad (0.24), and Burkina Faso (0.26) and the highest in Germany (0.90), South Korea (0.88) and America (0.86), respectively.

Discussion

This ecological study was performed to assess the correlation between air pollution and undernutrition in children under five years old. The results revealed a positive and direct correlation between the undernutrition in children under five years old and exposure to P.M2.5. Additionally, the study showed a negative and indirect correlation between undernutrition with HDI and SDI globally. Specifically, with an increase in exposure to P.M2.5, the prevalence of undernutrition (wasting) in children under five years old increases, while with an increase in both HDI and SDI, the prevalence of wasting decreases. Many studies have shown differences in the health associations for particulate matter across different countries, this highlights the need to prioritize clean air initiatives as a vital part of a broader strategy aimed at reducing pollution and preventing childhood undernutrition2,24,25. High HDI and high SDI countries generally exhibit better healthcare systems, more effective pollution control measures, and higher educational standards, collectively mitigating the adverse impacts of air pollution on child health26,27. Conversely, countries with medium to low HDI and low SDI face significant challenges due to weaker regulations, limited healthcare resources, and reliance on polluting fuels for cooking and heating26,27. This situation exacerbates the negative effects of air pollution, leading to higher malnutrition rates and related health issues among children26,27.

Combating malnutrition in all its forms is one of the biggest global health challenges28. PM2.5 was significantly associated with prevalence of wasting among children under five years old across all countries considered in our analysis. Previous studies also demonstrated the relationship between ambient PM2.5 exposure and adverse health outcomes14,29,30. A study by Unnati et al. in India showed that ambient PM2.5 exposure could be linked to anemia among children under five years old29. Odo et al. demonstrated that PM2.5 was associated with lower hemoglobin levels and increased odds of anemia in children under five years old residing in 36 countries30. Additionally, Exposure to PM2.5 air pollution is associated with respiratory symptoms, all-cause mortality, low birth weight, growth impairment, and undernutrition prevalence among children31,32,33,34.

This study revealed no significant association between stunting and exposure to P.M2.5. In contrast, Clarke et al. demonstrated that ambient PM2.5 is an environmental risk factor for lower height-for-age in young children across six East African countries14. This inconsistency may be due to adjustments for various confounders in the current studies or from differences in the countries studied.

Air pollution exposure, particularly to PM2.5, can lead to various disorders, including metabolic disorders, increased susceptibility to infections and nutritional imbalances35,36. Pollutants may alter how the body processes nutrients and manages energy balance, as they can disrupt metabolic functions by inducing inflammation and oxidative stress35. Also, air pollution can weaken the immune function, raising infection risk36,37. In children, this may cause frequent illnesses that lead to weight loss due to anorexia and higher metabolic demands36,37. This cycle worsens acute malnutrition and weight loss36,37. In addition, air pollution can interfere with the metabolism of vital nutrients such as retinol and iron37. This disruption causes these nutrients to be diverted to support immune responses instead of their usual functions37. This nutrient imbalance may lead to weight loss instead of stunting. HDI is associated with greater income per person, enabling families to access improved nutrition and healthcare services38. In contrast, regions with lower HDI frequently experience poverty, resulting in food insecurity and insufficient dietary quality, key contributors to stunting in children38. It seems that stunting is more common in children from countries with lower SDI due to limited access to healthcare, poor nutrition, and inadequate sanitation facilities39.

Stunting in childern is a complex issue that may need a multifaceted approach to address the high undernutrition rates in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups40. Socioeconomic Status (SES) plays a crucial role in moderating stunting, with significantly lower prevalence rates observed among children in the wealthiest quartile compared to those in the poorest quartile40. SES inequalities in stunting are highly persistent over time40,41. Our results suggest that stunting is less affected by acute environmental factors such as air pollution. It seems the stunting may be influenced by social and economic factors that modulate air pollution’s impact on growth.

While we observed that countries with higher HDI had a lower prevalence of wasting and stunting while countries with lower HDI had a higher prevalence of wasting and stunting. However, Interpreting the results of this study requires caution, as PM2.5 exposure might not be a direct cause of undernutrition but rather a symptom of adverse environmental and socioeconomic conditions. Countries with lower HDI and SDI often experience higher air pollution levels due to industrial activities, urbanization, and dependence on polluting fuels, for example, rising PM2.5 levels in sub-Saharan Africa are associated with increased childhood stunting, underscoring how economic constraints associated with health outcomes2,37.

The GNI is one component of HDI18. Thus, countries with lower GNI had a higher prevalence of wasting and stunting. Poverty disproportionately affects children, especially those residing in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia42. As a result, low- and middle-income countries such as India, Yemen, Burundi, Libya, Niger, and Sudan bear the highest burden of wasting and stunting worldwide. Ssentongo et al. showed a moderate association between a country’s HDI and undernutrition. Countries with lower HDI had a higher prevalence of undernutrition, including stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under five years old43. According to WHO, achieving undernutrition reduction targets in high-burden countries requires assessing current prevalence, projected population growth, underlying causes, available resources, setting annual reduction rates, mobilizing resources, and implementing systematic reduction plans44. Moreover, countries with higher welfare status and HDI tend to have a lower prevalence of wasting and stunting. Therefore, efforts to reduce PM2.5 air pollution exposure and enhance HDI at a country level can contribute to reducing undernutrition in young children. This research indicates high HDI and SDI significantly contributes to decreasing the prevalence of undernutrition among children under five years old. Policymakers must prioritize actions to address social inequality and vulnerability, particularly by minimizing community exposure to air pollution. This approach is crucial for promoting healthy development and preventing malnutrition in children under five years old.

Study strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge until the writing of this manuscript, one of the strengths of the present study was that it examined, for the first time, the relationship between air pollution and undernutrition in under five years old children in 123 countries. However, being an ecological study, researchers may encounter challenges in generalizing the results to the individual level due to the ecological fallacy. Because associations observed at the population level may not accurately represent those at the individual level. Additionally, since the study was conducted at the aggregate level rather than the individual level, researchers are unable to estimate the causal association between risk factors and outcomes. In addition, data quality may vary by country. It should also be noted that data on exposure to P.M2.5 were available for urban areas, while data on undernutrition were for all areas. Another limitation was that although SDI and HDI were considered as confounding factors, due to lack of access to data, the effects of other confounding factors such as the maternal education level, the occurrence of repeated infections, basic sanitation levels, access to healthcare, and food quality were not adjusted.

Conclusion

In this study, there was a positive correlation between exposure to PM2.5 air pollution and wasting in children under five years old. Also, there was a negative correlation between wasting and HDI. Additionally, there was a negative correlation between SDI and wasting. This study revealed that stunting had a significant inverse association with HDI and SDI, but it did not have a significant association with PM2.5 air pollution. Therefore, it is necessary to develop strategies for promoting HDI, SDI, air quality, and reducing exposure to PM2.5 on both national and international scales to reach sustainable development objectives, and eradicate malnutrition in children under five years old. Moreover, It is recommended to investigate the relationship between PM2.5 air pollution and undernutrition among children under five years old through studies conducted at various regional levels.

Data availability

Abbreviations

- PM2.5 :

-

Particulate Matter 2.5

- WLZ:

-

Weight-for-length z-score

- SDI:

-

Socio-Demographic Index

- HDI:

-

Human Development Index

- GNI:

-

Gross National Income

- IHME:

-

Health Metrics and Evaluation

- UNDP:

-

United Nations Development Programme

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic Status

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Malnutrition [Internet] 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition

Desouza, P. N. et al. Impact of air pollution on stunting among children in Africa. Environ. Health. 21, 128 (2022).

World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrition [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/2_background/en/index1.html

World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrition [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1

Khara, T. The relationship between wasting and stunting: policy, programming and research implications. Field Exch. 50, 23 (2016).

Unicef. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition (Esocialsciences, 2018).

Aguayo, V. M., Badgaiyan, N. & Dzed, L. Determinants of child wasting in Bhutan. Insights from nationally representative data. Public Health. Nutr. 20, 315–324 (2017).

Keel, J., Walker, K. & Pant, P. Air Pollution and its impacts on health in Africa-insights from the state of Global Air 2020. Clean. Air J. 30, 1–2 (2020).

Zhang, L., Wilson, J. P., MacDonald, B., Zhang, W. & Yu, T. The changing PM2. 5 dynamics of global megacities based on long-term remotely sensed observations. Environ. Int. 142, 105862 (2020).

Thangavel, P., Park, D. & Lee, Y. C. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2. 5)-mediated toxicity in humans: an overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 7511 (2022).

Wen, H. J., Wang, S. L., Wu, C. D. & Liang, M. C. Association of Asian dust storms and PM2. 5 with clinical visits for respiratory diseases in children. Atmospheric Environment, 120631 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Chronic exposure to ambient PM2. 5/NO2 and respiratory health in school children: a prospective cohort study in Hong Kong. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 252, 114558 (2023).

Cristaldi, A. et al. In vitro exposure to PM2. 5 of olfactory ensheathing cells and SH-SY5Y cells and possible association with neurodegenerative processes. Environ. Res. 241, 117575 (2024).

Clarke, K., Rivas, A. C., Milletich, S., Sabo-Attwood, T. & Coker, E. S. Prenatal exposure to ambient PM2. 5 and early childhood growth impairment risk in East Africa. Toxics 10, 705 (2022).

Amegbor, P. M., Sabel, C. E., Mortensen, L. H., Mehta, A. J. & Rosenberg, M. W. Early-life air pollution and green space exposures as determinants of stunting among children under age five in Sub-saharan Africa. Journal Exposure Sci. & Environ. Epidemiology, 1–15 (2023).

World Health Organization (WHO)/World Health Statistics. / Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/world-health-statistics

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. / IHME/ IHME Data/ Available from: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/ihme_data. [.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)/ Human Development Index (HDI)/ Available from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI..

Hayes, R. B. et al. PM2. 5 air pollution and cause-specific cardiovascular disease mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 25–35 (2020).

WHO Expert Committee on Physical Status: the Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. : Geneva, S., & Organization, W. H. (1995). Physical status: The use of and interpretation of anthropometry, report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva: World Health Organization. (1993). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37003.

Miles, J. R-squared, adjusted R‐squared. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (2005).

World Health Organization (WHO). Data. Prevalence of stunting in children under 5 (%) in 2022. Overview. Available from: https://data.who.int/indicators/i/5F8A486

Sokhi, R. S. et al. Advances in air quality research–current and emerging challenges. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions 1-133 (2021). (2021).

Kioumourtzoglou, M. A., Schwartz, J., James, P., Dominici, F. & Zanobetti, A. PM2. 5 and mortality in 207 US cities: modification by temperature and city characteristics. Epidemiology 27, 221–227 (2016).

Masselot, P. et al. Differential mortality risks associated with PM2. 5 components: a multi-country, multi-city study. Epidemiology 33, 167–175 (2022).

Cai, Y. S., Gibson, H., Ramakrishnan, R., Mamouei, M. & Rahimi, K. Ambient air pollution and respiratory health in sub-saharan African children: a cross-sectional analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 9729 (2021).

children’s Environmental Health Collaborative. Air pollution. The problem. Available from: https://ceh.unicef.org/spotlight-risk/air-pollution

World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrition [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_2

Mehta, U. et al. The association between ambient PM2. 5 exposure and anemia outcomes among children under five years of age in India. Environ. Epidemiol. 5, e125 (2021).

Odo, D. B. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) exposure and haemoglobin levels in children aged under 5 years living in 36 countries. Environ. Res. 227, 115734 (2023).

Pun, V. C., Dowling, R. & Mehta, S. Ambient and household air pollution on early-life determinants of stunting—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 26404–26412 (2021).

Chaudhary, E. et al. Cumulative effect of PM2. 5 components is larger than the effect of PM2. 5 mass on child health in India. Nat. Commun. 14, 6955 (2023).

Egondi, T., Ettarh, R., Kyobutungi, C., Ng, N. & Rocklöv, J. Exposure to outdoor particles (PM2. 5) and associated child morbidity and mortality in socially deprived neighborhoods of Nairobi, Kenya. Atmosphere 9, 351 (2018).

Bora, K. Air pollution as a determinant of undernutrition prevalence among under-five children in India: an exploratory study. J. Trop. Pediatr. 67, fmab089 (2021).

Luo, C. et al. The association between air pollution and obesity: an umbrella review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1856 (2024).

Mulat, E., Tamiru, D. & Abate, K. H. Impact of indoor Air Pollution on the Linear growth of children in Jimma, Ethiopia. BMC Public. Health. 24, 488 (2024).

Sinharoy, S. S., Clasen, T. & Martorell, R. Air pollution and stunting: a missing link? Lancet Global Health. 8, e472–e475 (2020).

Kismul, H., Acharya, P., Mapatano, M. A. & Hatløy, A. Determinants of childhood stunting in the Democratic Republic of Congo: further analysis of demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. BMC Public. Health. 18, 1–14 (2018).

Regassa, R., Belachew, T., Duguma, M. & Tamiru, D. Factors associated with stunting in under-five children with environmental enteropathy in slum areas of Jimma town, Ethiopia. Front. Nutr. 11, 1335961 (2024).

Bommer, C., Vollmer, S. & Subramanian, S. How socioeconomic status moderates the stunting-age relationship in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 4, e001175 (2019).

Bredenkamp, C., Buisman, L. R. & Van de Poel, E. Persistent inequalities in child undernutrition: evidence from 80 countries, from 1990 to today. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 1328–1335 (2014).

Jensen, S. K., Berens, A. E. & Nelson, C. A. Effects of poverty on interacting biological systems underlying child development. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 1, 225–239 (2017).

Ssentongo, P. et al. Global, regional and national epidemiology and prevalence of child stunting, wasting and underweight in low-and middle-income countries, 2006–2018. Sci. Rep. 11, 5204 (2021).

WHO. Global Nutrition Targets. : Policy Brief Series (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.2). Geneva: World Health Organization2014. (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Student Research Committee, Iran University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support for this study (Grant number: 27299; Ethics Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.1223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rozhan Khezri: data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and editing. Fatemeh Rezaei: project development and data analysis. Mitra Gholami: data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and editing. Sepideh Jahanian: manuscript writing, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khezri, R., Jahanian, S., Gholami, M. et al. The global air pollution and undernutrition among children under five. Sci Rep 15, 2935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87217-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87217-y

This article is cited by

-

Global occurrence of particulate matter 2.5 and its toxicological effects on human health: A systematic review

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2026)

-

Exposure to Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Risk of Adverse Health Outcomes in Women and Children in Bangladesh

Current Environmental Health Reports (2025)