Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major global health concern, with genetic factors influencing its development. This study investigated the genomic profile of Amazonian indigenous populations (INDG) by analyzing five genes—APC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2—associated with CRC. A total of 64 healthy individuals from 12 ethnic groups were analyzed using exome sequencing and bioinformatic tools. We identified 55 genetic variants, including three novel variants exclusive to the INDG, located in the MLH1 and MSH6 genes, which may represent genetic risks for CRC in this population. Additionally, three high-impact variants, already described in the literature, were identified in the APC and MSH2 genes. The study highlights the genetic isolation of Amazonian indigenous groups, with notable differences compared to continental populations. These findings emphasize the need for further genomic research to enhance the understanding of genetic risk factors and improve early detection and targeted therapies in vulnerable populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common tumor among all cancers. Globally, an estimated 1.93 million new cases and 916,000 deaths due to colorectal cancer1,2. CRC is a heterogeneous disease characterized by diverse clinical manifestations, molecular features, treatment sensitivities, and prognostic outcomes. The progression from adenoma to carcinoma involves a gradual accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations, leading to tumor development3.

The development of CRC may result from inherited oncogenes or mutations arising from microsatellite instability (MSI), chromosomal amplification, and translocation, driving the adenoma-to-carcinoma transformation4. Familial predisposition is observed in approximately 25% of all CRC cases5, with twin studies estimating the heritability rate at around 35%6,7. Hereditary syndromes associated with CRC are phenotypically classified into polypoid and non-polypoid syndromes8. Germline mutations with high penetrance contribute to 9% to 26% of CRC cases diagnosed before the age of 509.

According to the Americas Collaborative Group on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer (CGA-IGC), investigating hereditary syndromes in patients with CRC and/or polyposis requires the analysis of 11 key genes: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM, APC, BMPR1A, MUTYH, PTEN, STK11, and SMAD4. Among these, genes associated with Lynch Syndrome (LS) include MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS210. These genes are particularly relevant due to their cumulative lifetime risk of CRC by the age of 70, which ranges from 4 to 79% for MLH1, 35–77% for MSH2, 12–50% for MSH610,111, and 10–19% for PMS210,11. For the APC gene, associated with familial adenomatous polyposis, the risk is even higher, ranging from 69 to 100%10,12.

Large geographic variations significantly influence the incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer13. In Brazil, according to the National Cancer Institute, it is estimated that 45,630 new cases of colon cancer will occur annually during the 2023–2025 triennium, corresponding to an estimated risk of 21.10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Regarding mortality, in 2020, there were 20,245 deaths, corresponding to a rate of 9.56 per 100,000 inhabitants14.

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, the indigenous population residing in Brazil in 2022 was 1,693,535 individuals, representing 0.83% of the total population15. Studies on the molecular profile of CRC in the Brazilian population are particularly important due to its high genetic diversity. Furthermore, the literature highlights associations between genetic variants and CRC mortality in Brazilian individuals16,17. However, studies focusing on the incidence and prevalence of CRC in the indigenous population of the Amazon (INDG) remain scarce.

No studies have evaluated the impact of genetic variants in high-penetrance genes on the risk of developing CRC in Amazonian Amerindian populations. This gap underscores the potential significance of this study in advancing knowledge of genetic variants associated with hereditary colon cancer syndromes in a globally understudied population. Therefore, this research aimed to investigate the genomic profile of the INDG by analyzing five key genes (APC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) that play critical roles in the development of colorectal cancer.

Methods

Ethical aspects

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Committee (CONEP) under protocols No. 1062/2006 and 123/98 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All participants were asked to sign a written informed consent voluntarily before participation in the study along with the leaders of the respective ethnic groups with the assistance of a translator. The present study was conducted over a period of 13 months from September 2017 to December 2018.

Study and reference populations

For this descriptive cross-sectional study, a total of 64 healthy individuals from the Amazon were included in the indigenous population group (INDG). These individuals belong to 12 distinct ethnic groups: five Asurini of the Koatinemo, seven Arara of the Iriri, six Arawet’, 16 Asurini of the Trocar’a, seven AwaGuaj’a, one Munduruku, two Xikrins Odj’a, five Zo’ e, five Wajãpis, six Xikrin of the Catet’, two Karipunas, and two Jurunas. Further details about this population can be found in Rodrigues et al.18. The exome results were compared with data from accessible continental populations in the phase 3 release of the 1000 Genomes Project database (assembly GRCh38.p13; The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2015). This database includes 661 Africans (AFN), 347 Americans (AMR), 504 East Asians (EAS), 503 Europeans (EUR), and 489 South Asians (SAS). For variants not present in the 1000 Genomes platform, allele frequencies were obtained from the GnomAD v.3.1.2 database, which includes 20,744 Africans (AFN), 7647 Americans (AMR), 2604 East Asians (EAS), 34,029 non-Finnish Europeans (EUR), and 2419 South Asians (SAS).

DNA extraction and exome library preparation

The DNA extraction and exome library preparation for individuals in the INDG group were carried out according to the procedures outlined by Ribeiro-dos-Santos et al.19. For six additional individuals subsequently included in the group, the DNA extraction and exome library preparation processes are described in Rodrigues et al.18. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the phenol-chloroform method, and exome libraries were prepared using the Nextera Rapid Capture Exome (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and SureSelect Human All Exon V6 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) kits, following the manufacturers’ protocols. Sequencing was performed on the NextSeq 500® platform with the NextSeq 500 High-Output v2 kit (300 cycles)18.

Bioinformatic analysis

The sequences were initially filtered to remove low-quality reads using fastx_tools v.0.13 (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/), and then mapped and aligned to the reference genome (GRCh38) using the BWA v.0.7 tool (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Following alignment with the reference genome, the file was indexed and sorted using SAMtools v.1.2 (http://sourceforge.net/projects/samtools/). The alignment was then processed to remove duplicate sequences using Picard Tools v.1.129 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), recalibrate the mapping quality, and finalize local realignment using GATK v.3.2 (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us). Variant calling was performed with GATK v.3.2 to identify variants from the reference genome. Variant annotations were analyzed using the Variant Viewer (ViVa®) software. The variants were annotated in three databases: SnpEff v.4.3.T, Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (Ensembl version 99), and ClinVar (v.201810). For in silico prediction of pathogenicity, we used several databases: SIFT (v.6.2.1), PolyPhen-2 (v.2.2), LRT (November 2009), Mutation Evaluator (v.3.0), Mutation Provider (v.2.0), FATHMM (v.2.3), PROVEAN (v.1.1.3), MetaSVM (v.1.0), M-CAP (v.1.4), and FATHMM-MKL (http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/about.html).

Gene and variant selection

The selection of genes for this study was based on consulting the PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) database. The five selected genes (MLH1, MLH2, MSH6, PMS2 and APC) are among the most cited in the literature related to the inheritance of colorectal cancer. As for single nucleotide variants (SNVs), those that meet the following criteria were included: (i) a minimum of 10 coverage readings (determined using fastx_tools v.0.13); (ii) classification of the impact of the variant as modifier, moderate or high, predicted by the SnpEff software19; (iii) inclusion of new variants not previously documented.

Statistical analysis

The allele frequencies of genetic variants within the INDG group were determined using the allelic counting method and subsequently compared with reference populations (AFR, EUR, AMR, EAS and SAS) present in the 1000 Genomes platform and GnomaD. The variability of the interpopulation polymorphism was assessed using the Wright fixation index (TSF) and the subsequent Multidimensional Scale Analysis was performed. Comparisons of allele frequency differences between populations were conducted using Fisher’s exact test, with Hochberg’s correction applied for multiple comparisons, where a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. These statistical analyses were performed using Arlequin v.3.518 and RStudio v.4.2.3.

Results

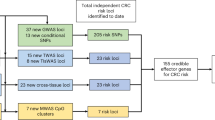

Among the 55 variants analyzed after the selection process, 15 belong to the APC gene, 10 to the MLH1 gene, 8 to the MSH2 gene, 9 to the MSH6 gene, and 13 to the PMS2 gene. Among these, 13 variants were predicted to have low impact, 28 with modifying impact, 11 with moderate impact, and three with high impact. The graph in Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the five genes across the 55 variants and presents the classification of variant impacts as low, moderate, modifier, and high.

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of variants predicted by the SnpEff software with high and moderate impact, including the affected gene, reference ID, clinical impact, and allele frequencies for the indigenous population as well as the five continental populations (AFR, AMR, EAS, EUR, and SAS) described in the 1000 Genomes and GnomAD databases. Variants with low and modifier impacts are detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

In our study, we identified variants related to colorectal cancer that have not yet been described in the literature and may be exclusive to the indigenous population of the Amazon under investigation. Table 2 presents three new variants, along with their respective genes, chromosomal positions, detailed regions, wild and mutant alleles, mutation impacts, and the type of alteration they generate in protein formation, based on in-silico predictions from SnpEff. The identified variants were classified as having modifier impact and are associated with intron-type mutations. Two of these variants are located in the MLH1 gene, and one is in the MSH6 gene.

Figure 2 presents a graph demonstrating Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) analysis using FST values and population genotypes to compare the 55 variants in the genes. The genotypic differences of the indigenous population are evident when compared to other populations. Considering only the exomes of the genes studied, genomic similarities are observed between the AMR, EUR, and SAS populations. In contrast, the other groups (INDG, EAS, and AFR) are positioned at the extremes of the graph, with the INDG, AFR, and EAS populations showing greater genetic difference for the genes investigated in this study.

Discussion

Considering the limited studies involving indigenous populations, the high global incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC), and the need to assess the susceptibility of the studied population to hereditary forms of the disease, our research constitutes the first genomic investigation into CRC heritability in Amazonian Amerindian populations. Genetic variants already described in the literature have been firmly associated with hereditary colorectal cancer4.

Hereditary colorectal cancer is most commonly represented by familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC). In both conditions, disease predisposition is linked to gene mutations inherited in an autosomal dominant manner20. In FAP, mutations in the APC gene lead to the development of numerous colorectal polyps, with an almost 100% risk of malignant transformation within 10 to 15 years of polyp formation. In HNPCC, mutations in DNA repair genes such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 are associated with a roughly 80% risk of malignant transformation4,21. Our study analyzed these five genes, identifying 55 variants, the general characteristics of which are described in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Notably, three of these variants were exclusive to the indigenous population of the Amazon (Table 2).

We evaluated the variability of these variants among the indigenous populations of the Amazon and the five populations from the 1000 Genomes Project associated with the genes investigated. The isolation of the African population (Fig. 2) is expected due to its high genetic diversity compared to non-African populations, as it represents the formative population22. The INDG and AMR groups did not show the genetic similarity among the five genes analyzed, despite the common ancestry shared between Amerindians and Latin Americans. This divergence reflects the different historical contexts in the formation and genetic composition of Latin American populations, which were shaped by the ancestral contributions of Amerindians23. The genetic isolation of the Amazonian indigenous group from other global populations is known, as other studies have also found this distinction in different contexts24.

The work by dos Santos (2019) is important in tracing the molecular profile of CRC patients, examining several genes and profiling patient ancestry. However, it differs from our findings in that the sample studied in the southeastern region of Brazil has only an estimated 4% Native American ancestry17. In contrast, our samples represent indigenous patients and highlight the presence of three new variants—two in the MLH1 gene and one in the MSH6 gene. This variation underscores the divergence in gene profiles across regions of Brazil, especially in the Amazon, which has a high degree of miscegenation with Amerindian populations.

Functional deficiency of DNA repair protein (MMR) is one of the factors that favors the development of neoplasms and is associated with Lynch Syndrome25. Studies carried out by Brazilian researchers have highlighted the role that the association of the MMR mutation in the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 genes exert in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer and clinical characteristics suggestive of Lynch Syndrome, the patients studied belong to three regions of Brazil in the south region, southeast region and north region26,27. The results found by Shneider (2018) suggest that the variants present in the MSH6 gene are not common among Brazilian patients with Lynch Syndrome diagnosed with CRC26. In addition, the strategies adopted by Soares (2020) to identify the variants present in the MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 genes reduced the time to diagnosis for colorectal cancer26.

An important result in our analyses was the discovery of three novel variants localized to important DNA repair genes in our study population. Two of these variants were in the MLH1 gene, an important tumor suppressor involved in DNA derangement repair28,29. The third variant was found in the MSH6 gene, a protein-coding gene that is related to DNA repair pathways30. These variants require further characterization in functional studies to allow more information about colorectal cancer in the Amazonian indigenous population.

Regarding the high-impact variants identified in our study population, two are present in the APC gene (rs2229992 and rs41115), one in the MSH2 gene (rs1060502002), an important DNA repair gene. In several studies APC has been considered a gatekeeper gene for most colorectal cancer cases, this gene may also be involved in other cellular processes, including cell migration and adhesion, transcriptional activation, apoptosis, and DNA repair31,32,33,34. Studies indicate that APC inactivation is an event that occurs early in the development of CRC and may play a key role in the initiation of the adenoma-carcinoma pathway31,35. In addition, several studies on the molecular classification of CRC have been reported16,32,36,37. However, although APC is the most frequently mutated and known driver gene in CRC31, it is generally not included as a factor in the clinical prognostic classification and standard sequencing panels of colorectal cancer32.

In addition, APC mutations are more frequent in MSI-negative tumors38,39. In order to evaluate the long-term outcome of the MSI status of more than a thousand Brazilians with colorectal cancer and associate them with genetic ancestry and molecular and clinical-pathological characteristics, a study by Berardinelli (2022) observed a 10% frequency of MSI, tumors preferentially located in the right colon, of less aggressiveness and with significant differences in the survival of these patients, who had alterations in several MSI target genes, especially those related to functions such as DNA repair, DNA damage sensor, and cell signaling, demonstrating the genetic heterogeneity present in these patients39.

Torrezan (2013) evaluated the mutational spectrum of the APC gene and genotype–phenotype correlations in Brazilian patients with classic or attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. The self-declared ethnic origin of most of the families evaluated in this study is of European descent, except for two Japanese families and one Arab40. However, we highlight that Brazilians represent an extremely mixed population, with most individuals showing some degree of indigenous ancestry, especially in the northern region of the country.

Notably, no previous studies have established a direct link between these variants and colorectal cancer susceptibility in the INDG population. This highlights that research findings from other populations cannot be directly applied to the Amazonian Amerindian population, emphasizing its distinct genetic profile in relation to various aspects, including CRC. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more genomic research involving this population to identify potential markers for early diagnosis and even molecular targets for therapeutic purposes in Northern Brazil’s population.

In conclusion, this study highlights the presence of high-impact variants, specifically APC rs2229992 and rs41115, and MSH2 rs1060502002, alongside novel modifier-impact variants in the MLH1 and MSH6 genes within indigenous populations. These findings suggest that these variants may significantly influence colorectal cancer (CRC) susceptibility. As the first investigation into the genomic profile of CRC in Amazonian Amerindians, this research provides valuable insights that may guide future studies aimed at identifying populations with higher susceptibility to CRC. This work underscores the importance of further genomic research to enhance our understanding of genetic risk factors and inform strategies for early detection and targeted therapies in vulnerable populations.

Data availability

The data from the public domain are available at 1000 Genomes Project database (assembly GRCh38.p13; The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2015) and gnomAD (broadinstitute.org), and the sequencing data of the Amazonian Ameridian populations are available at the ENA database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB35045) under the accession number PRJEB35045.

References

WHO. Cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed 14 Jan 2024. (2024).

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.fr/today. Accessed 04 May 2024. (2024).

Rodriguez-Salas, N. et al. Clinical relevance of colorectal cancer molecular subtypes. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 109, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.11.007 (2017).

Figueiredo, E. M. A., Correia, M. M. & Oliveira, A. F. Tratado de Oncologia 833–861 (Revinter, 2013).

Mork, M. E. et al. High prevalence of hereditary cancer syndromes in adolescents and adults with colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3544–3549 (2015).

DeRycke, M. S. et al. Targeted sequencing of 36 known or putative colorectal cancer susceptibility genes. Mol. Gene Genom. Med. 5, 553–569 (2017).

Pearlman, R. et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 3, 464–471 (2017).

Daca Alvarez, M. et al. The inherited and familial component of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cell 10, 710 (2021).

Stoffel, E. M. et al. Features germline genetics of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 154, 897-905.e1 (2018).

Heald, B. et al. Collaborative group of the Americas on inherited gastrointestinal cancer. Collaborative group of the Americas on inherited gastrointestinal cancer position statement on multigene panel testing for patients with colorectal cancer and/or polyposis. Fam. Cancer 19(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-020-00170-9 (2020).

Riley, B. D. et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 21(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x (2012).

Syngal, S. et al. American college of gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110(2), 223–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.435 (2015).

Morgan, E. et al. The global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327736 (2022).

José Alencar Gomes da Silva National Cancer Institute (INCA). 2023 Estimate: Cancer Incidence in Brazil. Ministry of Health: Brasilia, Brazil. (2022).

Indigenous Brazil. https://indigenas.ibge.gov.br/images/pdf/indigenas/folder_indigenas_web.pdf. Accessed on 13 June 2023. (2023).

Gomes-Fernandes, B. et al. Association between KRAS mutation and alcohol consumption in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 14, 26445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75048-2 (2024).

dos Santos, W. et al. Mutation profile of cancer factors in Brazilian colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 9, 13687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-496 (2019).

Rodrigues, J. C. G. et al. Identification of NUDT15 genetic variants in Amazonian Amerindians and mixed individuals from northern Brazil. PLoS One 15(4), e0231651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231651 (2020).

Ribeiro-dos-Santos, A. M. et al. Exome sequencing of native populations from the Amazon reveals patterns on the peopling of South America. Front. Genet. 11, 548507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.548507 (2020).

Deen, K. I., Silva, H., Deen, R. & Chandrasinghe, P. C. Colorectal cancer in young people, too many questions, too few answers. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 8(6), 481–488 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. Selective targeting of mutant adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in colorectal cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8127 (2016).

Hollfelder, N., Breton, G., Odin, P. & Jakobsson, M. The deep population history in Africa. Hum. Mol. Genet. 30(R1), R2–R10. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddab005 (2021).

Skoglund, P. & Reich, D. A. Genomic view of the peopling of the Americas. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 41, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2016.06.016 (2016).

Rodrigues, M. M. O. et al. Blood groups in native Americans: A look beyond ABO and Rh. Genet. Mol. Biol. 44(2), e20200255. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2020-0255 (2021).

Bateman, A. C. DNA mismatch repair proteins: scientific update and practical guide. J. Clin. Pathol. 74(4), 264–268. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2020-207281 (2021).

Schneider, N. B. et al. Germline MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 variants in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer and clinical features suggestive of Lynch Syndrome. Cancer Med. 7(5), 2078–2088. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1316 (2018).

Soares, B. L. et al. Screening for germline mutations in mismatch repair genes in patients with Lynch syndrome by next generation sequencing. Fam. Cancer 17, 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-017-0043-5 (2018).

Caspers, I. A. et al. Netherlands foundation for detection of hereditary tumours collaborative investigators. Gastric and duodenal cancer in individuals with Lynch syndrome: a nationwide cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 69, 102494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102494 (2024).

Yamamoto, G. et al. Concordance between microsatellite instability testing and immunohistochemistry for mismatch repair proteins and efficient screening of mismatch repair deficient gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 26(5), 494 (2023).

Idos, G. & Valle, L. Lynch Syndrome. In GeneReviews® (eds Adam, M. P. et al.) 1993–2024 (University of Washington, 2004).

Fearon, E. R. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 6(1), 479–507. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235 (2011).

Schell, M. et al. A multigene mutation classification of 468 colorectal cancers reveals a prognostic role for APC. Nat. Commun. 7, 11743. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11743 (2016).

Nallamilli, B. R. R. & Hegde, M. Detecting APC gene mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphg.29 (2017).

Torrezan, G. T. et al. Mutational spectrum of APC and MUTYH genes and genotype-phenotype correlations in Brazilian patients with FAP, AFAP and MAP. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-54 (2013).

Cross, W. et al. The evolutionary landscape of colorectal tumorigenesis. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2(10), 1661–1672. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0642-z (2018).

De Sousa, M. F. et al. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat. Med. 19, 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3174 (2013).

Sadanandam, A. et al. A colorectal cancer classification system that associates cellular phenotype and responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 19, 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3175 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Comparative molecular analysis of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell 33(4), 721-735.e8 (2018).

Berardinelli, G. N. et al. Advantage of HSP110 (T17) marker inclusion for microsatellite instability (MSI) detection in colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget 9(47), 28691–28701. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25611 (2018).

Torrezan, G. T. et al. Mutational spectrum of the APC and MUTYH genes and genotype-phenotype correlations in Brazilian FAP, AFAP, and MAP patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 5(8), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-5 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.d.S., A.C.A.d.C. and N.P.C.d.S.; Methodology, A.M.R.-d.-S. and J.C.G.R.; Formal Analysis, J.C.G.R., N.M. and L.W.M.S.V.; Resources, M.R.F., R.M.R.B., S.E.B.d.S. and Â.R.- d.-S.; data curation, J.F.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, I.B.d.S. and A.C.A.d.C., Writing—review and editing, L.P.A.G., L.L.S.S., F.C.A.d.M., T.C.d.B.A. and M.O.M.S.; supervision, N.P.C.d.S. and S.E.B.d.S.; project administration, A.M.R.-d.-S., Â.R.-d.-S., M.R.F., N.P.C.d.S. and S.E.B.d.S.; funding acquisition, Â.R.-d.-S., P.P.d.A., N.P.C.d.S. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, I.B., da Costa, A.C.A., Gellen, L.P.A. et al. Identification of genomic variants associated with colorectal cancer heredity in indigenous populations of the Amazon. Sci Rep 15, 14616 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87401-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87401-0