Abstract

In the present digital scenario, the explosion of Internet of Things (IoT) devices makes massive volumes of high-dimensional data, presenting significant data and privacy security challenges. As IoT networks enlarge, certifying sensitive data privacy while still employing data analytics authority is vital. In the period of big data, statistical learning has seen fast progressions in methodological practical and innovation applications. Privacy-preserving machine learning (ML) training in the development of aggregation permits a demander to firmly train ML techniques with the delicate data of IoT collected from IoT devices. The current solution is primarily server-assisted and fails to address collusion attacks among servers or data owners. Additionally, it needs to adequately account for the complex dynamics of the IoT environment. In a large-sized big data environment, privacy protection challenges are additionally enlarged. The data dimensional can have vague meaningful patterns, making it challenging to certify that privacy-preserving models do not destroy the efficacy and accuracy of statistical methods. This manuscript presents a Privacy-Preserving Statistical Learning with an Optimization Algorithm for a High-Dimensional Big Data Environment (PPSLOA-HDBDE) approach. The primary purpose of the PPSLOA-HDBDE approach is to utilize advanced optimization and ensemble techniques to ensure data confidentiality while maintaining analytical efficacy. In the primary stage, the linear scaling normalization (LSN) method scales the input data. Besides, the sand cat swarm optimizer (SCSO)-based feature selection (FS) process is employed to decrease the high dimensionality problem. Moreover, the recognition of intrusion detection takes place by using an ensemble of temporal convolutional network (TCN), multi-layer auto-encoder (MAE), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) models. Lastly, the hyperparameter tuning of the three models is accomplished by utilizing an improved marine predator algorithm (IMPA) method. An extensive range of experimentations is performed to improve the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique’s performance, and the outcomes are examined under distinct measures. The performance validation of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique illustrated a superior accuracy value of 99.49% over existing models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In information technology, cybersecurity is the most demanding research topic at present. It is mainly challenging to attain when evolving technology, like the IoT, is concerned1. This development poses a vast threat to data confidentiality, availability, and integrity that malicious actions might utilize. There is more attention on IoT security as several novel applications that depend on connected devices have advanced2. With the high popularity of IoT, assaults against connected devices are one of the vital issues. The IoT devices are exposed to attacks through numerous methods, such as privilege escalation, denial of service, and eavesdropping. As an outcome, the necessity to defend IoT devices from these assaults is becoming gradually significant3. Besides, numerous devices in an incorporated network trust a wireless network for realistic communication, which is vulnerable to eavesdropping; so, the network is subjected to cyberattacks. Therefore, enhanced and extremely robust intrusion detection systems (IDS) are required for IoT devices. IDS aids in observing and examining the services, data, and network and analyzing within its effectual network management and classification of exposures in the least period4. Detecting intruders is a significant stage in certifying IoT networks’ safety. Intrusion detection is the protection mechanism for handling safety intrusions5. IDS is the primary tool employed to secure conventional information systems and networks. It observes the processes of a network or a host, informing the system administrator when it identifies a security intrusion. IDS recognizes unauthorized intrusions, attacks, and malicious actions in the network and creates one of the foremost security actions in the current network6.

The development of advanced technologies like the IoT with storage resources has resulted in the invention of big data. This has resulted in huge data generation by human beings over IoT-based sensors and devices, thus altering the production of various features7. Providing privacy and protection for big data is the biggest challenge facing developers of security management systems, particularly with the prevalent usage of the internet networks and the fast evolution of data produced from multiple resources; this generates more space for intruders to commence malicious attacks. Figure 1 represents the structure of big data. New attacks are being developed frequently, while insiders take advantage of their authorization to access the system to attack, leaving restricted suspicious tracks behind8. The conventional knowledge-based IDS should give mode to intelligent and data-driven networks. Unlike other models, intrusion detection based on deep learning (DL) and ML achieves superiority over other models. The DL has robust capabilities, such as good generalization, self-adaptation, self-learning, and recognition against unknown attack behaviour9. Meanwhile, the ML models are also flexible and scalable and, in numerous ways, can meet the exclusive demands of IoT security better than any other technique presently utilized10. On the other hand, the DL techniques extract features independently, can handle vast amounts of data, and beat classical ML in accuracy and performance.

This manuscript presents a Privacy-Preserving Statistical Learning with an Optimization Algorithm for a High-Dimensional Big Data Environment (PPSLOA-HDBDE) approach. The primary purpose of the PPSLOA-HDBDE approach is to utilize advanced optimization and ensemble techniques to ensure data confidentiality while maintaining analytical efficacy. In the primary stage, the linear scaling normalization (LSN) method scales the input data. Besides, the sand cat swarm optimizer (SCSO)-based feature selection (FS) process is employed to decrease the high dimensionality problem. Moreover, the recognition of intrusion detection takes place by using an ensemble of temporal convolutional network (TCN), multi-layer auto-encoder (MAE), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) models. Lastly, the hyperparameter tuning of the three models is accomplished by utilizing an improved marine predator algorithm (IMPA) method. An extensive range of experimentations is performed to improve the performance of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique, and the outcomes are examined using distinct measures. The major contribution of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique is listed below.

-

The LSN is utilized to scale input data effectually, confirming consistent feature ranges. This preprocessing step substantially improved the performance of subsequent models by enhancing their convergence and accuracy. Furthermore, it facilitated enhanced feature interpretability and mitigated the impact of noise in the data.

-

A SCSO-based FS process is implemented to handle the dataset’s high dimensionality threats. This methodology enhanced the model’s efficiency by mitigating computational complexity and improved accuracy by retaining the most relevant features. Ultimately, it resulted in more robust and reliable model performance in intrusion detection tasks.

-

An ensemble approach was utilized, integrating a TCN, MAE, and XGBoost for robust intrusion detection. This incorporation employed the merits of every model, improving overall detection accuracy and resilience against various attack patterns. The ensemble approach portrayed superior performance related to individual models, crucially enhancing the intrusion detection capabilities.

-

Optimized performance of the models is attained via hyperparameter tuning using an IMPA technique. This methodology systematically explored the parameter space, confirming the optimal settings for every method were detected. As a result, the overall efficiency and reliability of the IDS were substantially improved.

-

Integrating several advanced methods, including LSN, SCSO, ensemble models, and IMPA, creates a unique framework for improving IDSs. This methodology emphasizes enhanced accuracy and effectiveness and cohesively addresses the threats of high dimensionality and model optimization. The novelty is in the synergistic combination of these techniques, which collectively outperform conventional models in real-world applications.

Review of literature

Haseeb et al.11 present an AI-aided route method for mobile wireless sensor networks (MWSN) to enhance energy and identify transmission link errors. Furthermore, the presented smart security technique upsurges the reliability of the restraint devices on random paths. Initially, it discovers a metaheuristic optimizer, a genetic algorithm (GA) system to identify the possible solutions, and depending upon independent metrics, it creates an optimum set of routings. Next, novel routes were recognized utilizing dynamic decisions to fulfil energy concerns. In12, a new Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based Energy-aware IDS and Safe routing method is presented to improve a secured IWSN. Primarily, the presented method performs the IDS to classify several attacks. Later, a game strategy-based decision device is incorporated with the presented ID method to decide whether security is required. In the latter stage, an energy-aware ad-hoc on-demand distance vector method is recognized to deliver a safe routing between the several nodes. Ntizikira et al.13 present the honeypot and blockchain (BC)-based ID and prevention (HB-IDP) method, in which edge computing is proposed to decrease the latency in transmission. Primarily, three-fold verification was executed utilizing the camellia encryption algorithm (CEA), which offers confidential keys. The method executes preprocessing by utilizing the min-max normalization. Signature-based ID is executed on the data preprocessed, with well-known assaults categorized into three modules utilizing the improved isolation forest (IIF) method. Kipongo et al.14 propose an improved honeycomb structure-based IDS for SDWSN that contains safe verification utilizing the 3D cube method, improved honeycomb-based network reinforcement learning (RL), clustering-based smart routing with a transfer learning (TL)-based deep Q networks (TLDQNs), and a hybrid IDS. In15, an advanced network IDS was proposed for an IoT-based intelligent home atmosphere. Separate from present methods, the overall approach offers a method and integrates IoT devices as possible vectors in the cyber attack environments, a concern frequently ignored in the preceding study. Using the harmony search algorithm (HSA), the method developed the extra trees classifier (ETC) by enhancing a widespread array of hyperparameters. Shitharth et al.16 proposed a multi-attack IDS for edge-aided IoT, which unites the backpropagation NN (BPNN) with the Radial basis function (RBF) NN. A backpropagation NN is mainly used to identify outliers and zero down on the most significant features for every attacking approach. An NN depending on RBF is utilized to identify multi-attack intrusions. Sajid et al.17 presented a hybrid method for ID with DL and ML methods to address these restrictions. The presented technique uses CNN and XGBoost methods for extracting the feature and then unites them all with the LSTM technique for identification.

Salama and Ragab18 present a new BC with an Explainable AI-driven ID for the IoT-driven Ubiquitous Computing System (BXAI-IDCUCS) method. The BXAI-IDCUCS method primarily groups the IoT nodes using an energy-aware duck swarm optimizer (EADSO). DNN is also used to classify and detect data. Finally, the BC technique is used for safe inter-cluster data communication procedures. Vakili et al.19 propose a service composition methodology by utilizing Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) and MapReduce framework to compose services with optimized QoS. Ntizikira et al.20 present the Secure and Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection and Prevention for UAVS (SP-IoUAV) model by using federated learning (FL), differential privacy, and CNN-LSTM for real-time anomaly detection. Heidari et al.21 present an algorithm for constructing an optimal spanning tree by incorporating an artificial bee colony (ABC), genetic operators, and density correlation. Heidari, Navimipour, and Unal22 propose a BC-based RBF neural networks (RBFNNs) model. Heidari et al.23 present a model using fault trees and Markov chain analysis. Wang et al.24 introduce the DL-BiLSTM lightweight IoT intrusion detection model, which integrates deep neural networks (DNNs) and bidirectional LSTMs (BiLSTMs) for effectual feature extraction. The method employs an incremental principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction. Zanbouri et al.25 propose a Glowworm Swarm Optimization (GSO) model to optimize performance in BC-based Industrial IoT (IIoT) systems. Zhang et al.26 introduce a dispersed privacy-preserving energy scheduling methodology using multi-agent deep RL (DRL) for energy harvesting clusters. Amiri, Heidari, and Navimipour27 introduce a novel taxonomy of the DL method. Devi and Arunachalam28 present a method that utilizes DL to detect attack nodes with a deep LSTM classifier. The Improved Elliptic Curve Cryptography (IECC) approach is employed for prevention, with hybrid MA-BW optimization for optimal key selection. Wang et al.29 propose a high-dimensional temporal data publishing methodology by utilizing dynamic Bayesian networks and differential privacy. The approach constructs a network based on mutual data, assesses edge sensitivity with Coherent Neighborhood Propinquity, and adds noise to attributes to meet ε-differential privacy standards. Younis et al.30 introduce FLAMES2Graph, a horizontal FL framework. Zhao et al.31 present the Variational AutoEncoder Gaussian Mixture Model Clustering Vertical FL Model (VAEGMMC-VFL) model. Chougule et al.32 introduce a Privacy-Preserving Asynchronous FL model. El-Adawi et al.33 propose a model using Gramian angular field (GAF) and DenseNet. The approach comprises preprocessing signals through artefact removal and median filtering (MF), then converting time series data into 2D images utilizing the GAF approach. Zainudin et al.34 present an FL framework employing Chi-square and Pearson correlation coefficient methods. Bushra et al.35 introduce the attention-based random forest (ABRF) with stacked bidirectional gated recurrent unit (stacked Bi-GRU) methodology.

Hou et al.36 propose the adaptive training and aggregation FL (ATAFL) framework through a joint optimization problem. The model also incorporates the digital twin and DRL model for optimal node selection and resource allocation. Jiang et al.37 propose a FL framework utilizing a conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) method. Additionally, the model suggests an FL scheme, namely FedDWM, which effectually combines local model parameters from terrestrial clients to satellite servers. Feng et al.38 present a model sparsification strategy by employing contrastive distillation; the framework enhances local-global model alignment and maintains performance. Abdallah et al.39 explore existing ML and DL methods for detecting anomalies. Shan et al.40 introduce the CFL-IDS framework by employing local models’ evaluation metrics. An intelligent, cooperative model aggregation mechanism (ICMAM) method optimizes local model weights and reduces interference from subpar models. Babu, Barthwal, and Kaluri41 propose a trusted BC system for edge-based 5G networks. Begum et al.42 improve data safety by utilizing a secret key to scramble input, applying the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT), and compressing the result with Move-To-Front and Run-Length Encoding, integrating cryptographic principles to improve performance. Babu et al.43 introduce a cooperative flow in fog-enabled IoT networks utilizing a permissioned BC system. Devarajan et al.44 present the adapted particle swarm optimization integrated FL-based sentiment analysis integrated deep learning (aPSO-FLSADL) for sentiment analysis. The method also utilizes SentiWordNet for sentiment scoring and BERT for word embedding, with a CNN-BiLSTM model for training. Yenduri et al.45 explore how BC technology enhances protection and transparency. Hao et al.46 propose a protocol for wireless applications in the multi-server environment. Saheed et al.47 present a hybrid model by integrating Autoencoder and Modified Particle Swarm Optimization (HAEMPSO) for feature selection, with a DNN for classification by optimizing DNN parameters by utilizing a modified inertia weight in PSO. Saheed, Abdulganiyu, and Tchakoucht48 introduce the IoT-Defender framework integrating a Modified Genetic Algorithm (MGA) with a deep Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network for cyberattack detection in IoT networks. Saheed, Omole, and Sabit49 present the GA-mADAM-IIoT model by integrating a GA, attention mechanism, and modified Adam-optimized LSTM across six modules.

Heidari et al.50 provide insights into the generation and detection of deepfakes, explore recent improvements, detect weaknesses in current security methods, and emphasize areas needing additional research. Heidari et al.51 introduce a BC-based FL solution incorporating SegCaps, CNN, and capsule networks for enhanced image feature extraction, data normalization, and confidentiality in global model training. Boopathi et al.52 propose a strategy to improve edge computing data privacy by utilizing secure transfer, DL optimization, and trust-based encryption with hybrid federated networks. Heidari, Navimipour, and Otsuki53 review the challenges and merits of Cloud Non-destructive Characterization Testing (CNDCT), comparing cloud-based testing environments with conventional system testing techniques. Asadi et al.54 provide a comprehensive overview of botnets, their evolution, detection methods, and evasion techniques while underscoring future research directions for combating these security threats. Ramkumar et al.55 propose the GACO-MLF framework, using ML and an enhanced ant colony optimization (ACO) model for balancing loads efficiently across IoT-PCN data centres. Heidari, Jamali, and Navimipour56 propose fuzzy multicriteria decision-making (MCDM)--based re-broadcasting scheme (FMRBS) for VANETs to reduce broadcast storms and improve data distribution. Saini et al.57 propose a trust-based, hybrid privacy-preserving strategy for cloud computing. Dansana, Kabat, and Pattnaik58 introduce an ML-based perturbation approach utilizing clustering, IGDP-3DR, and SVD-PCA for dimensionality reduction, followed by classification with KSVM-HHO for improved accuracy. Zhang and Tang59 propose the VPPLR framework for secure logistic regression training, utilizing secret sharing and a vectorization approach for effectual global parameter updates, bypassing homomorphic encryption. Jadhav and Borkar60 developed a data sanitization technique using the Marine Predator Whale Optimization (MPWO) approach to generate optimal keys, preserving the privacy of sensitive data. Vasa and Thakkar61 explore methods for protecting privacy in DL models for big data, discussing potential attacks and privacy protection approaches and proposing an effectual solution for enhancing privacy in DL models. Jahin et al.62 highlight the requirement for varied forecasting based on SC objectives, optimizing models using KPIs and error measurements. Bajpai, Verma, and Yadav63 propose a novel methodology integrating extended PCA and reinforcement learning to enhance clustering, data reduction, network service life, energy efficiency, and data aggregation. Song et al.64 present a GCNN-IDS approach that uses gene expression programming (GEP) to optimize CNN parameters, preventing local optima through global search capabilities.

Chen and Huang65 developed a privacy-preserving FL methodology to predict airline passengers’ willingness to pay for upgrades by securely incorporating multi-source data without compromising customer privacy. Dodda et al.66 examine three privacy-preserving algorithms—regularized logistic regression with DP, SGD with private updates, and distributed Lasso—underscoring the impact of training data volume on error rates and privacy. Kamatchi and Uma67 present an FL approach for detecting and reducing insider threats in IoT devices. It utilizes hybrid RSA and elliptic curve digital signatures for user registration, node clustering for privacy, and federated optimization with secure hashing for improved protection. Dhavamani et al.68 propose an enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) approach for achieving differential privacy in IoT data sharing, optimizing privacy-preserving mechanisms while maintaining data utility through improved fitness functions, dynamic inertia weight, and adaptive coefficients. Xia69 propose Split Federated Mutual Learning (SFML), an FL approach for traffic classification that uses split and mutual learning, where clients maintain privacy and public models, sharing knowledge through distillation while offloading computation to the server. Liu70 present Hilbert-ConvLSTM, a novel DL method for location data prediction that enhances data availability and user privacy. It also utilizes Hilbert curve partitioning, spatio-temporal feature extraction, and differential privacy with Laplace noise to protect user information. Chowa et al.71 present a privacy-preserving self-supervised framework for COVID-19 classification from lung CT scans utilizing FL and Paillier encryption, ensuring secure decentralized training with unlabeled datasets from multiple hospitals. Huang et al.72 present GeniBatch, a batch compiler that optimizes PPML programs with PHE for efficiency, ensuring result consistency and preventing bit-overflow. Integrated into FATE, it utilizes SIMD APIs for hardware acceleration. Hossain et al.73 propose a privacy-preserving SSL-based Intrusion Detection System for 5G-V2X networks, using unlabeled data for pre-training and minimal labelled data for post-training, improving cyber-attack protection without compromising privacy.

Bezanjani et al.74 propose a three-phase methodology: blockchain-based encryption for secure transactions, request pattern recognition to detect unauthorized access, and BiLSTM-based feature selection for enhanced intrusion detection accuracy. Deebak and Hwang75 introduce a privacy-preserving learning mechanism for failure detection, using lightweight model aggregation at the edge and a 2D-CNN for improved privacy protection and accuracy without extra verifiability. Zhou et al.76 propose PPML-Omics, a secure ML method using decentralized differential private FL, ensuring privacy protection while analyzing omic data across diverse sequencing technologies and DL techniques. Babu et al.77 explore the challenges and solutions in managing IoT data, focusing on scalable modelling, real-time processing, and security. It highlights the significance of feature engineering and model selection for effectual IoT data analysis, contributing to improved decision-making and operational efficiency in IoT applications. Li et al.78 present a lightweight privacy-preserving predictive maintenance technique using binary neural networks (BNNs) and homomorphic encryption for privacy protection in 6G-IIoT scenarios. Li et al.79 propose a new training metric, Intra-modal Consistent Contrast Loss, to improve image-text retrieval accuracy. A quadtree index structure with hybrid representation vectors mitigates retrieval overhead, while encrypted feature vectors enable secure image-text matching in a large-scale ciphertext environment. Yang et al.80 propose a privacy-preserving ML model using a cloud-edge-end architecture, optimizing IoT systems by offloading tasks to edge servers and using homomorphic encryption, secret sharing, and differential privacy for improved privacy and reduced computational burden. Mumtaz et al.81 explore privacy-preserving data analysis methods utilizing AI-based approaches like differential privacy, FL, GANs, and VAEs, emphasizing their efficiency in protecting privacy while analyzing data. Keerthana82 examine the tactics and methods utilized in FL to preserve privacy during cooperative model training across dispersed devices, ensuring data security in ML workflows. Zhang et al.83 introduce SensFL, a privacy-enhancing methodology for protecting against privacy inference attacks in VFL by regularizing embedding sensitivity, preventing data reconstruction. Iam-On et al.84 propose a bi-level ensemble clustering framework that ensures data privacy and mitigates complexity by choosing multiple clusterings from each segment.

The existing studies present diverse enhancements in intrusion detection and prevention systems across various contexts. One approach improves mobile WSNs by employing a GA to optimize routing and enhance energy efficiency. Another technique concentrates on AI-based IDSs that classify attacks and integrate game theory for secure routing. A honeypot and BC-based strategy is presented to mitigate latency in data transmission, while an en enhanced honeycomb structure integrates RL and clustering for robust security. Methods utilizing DL classifiers and hybrid methods aim to address threats safeguarding IoT devices, including using optimized algorithms for feature extraction and improving model performance. Additionally, FL frameworks are presented to ease secure data sharing and decision-making, incorporating real-time anomaly detection mechanisms. Other proposals accentuate energy-aware scheduling and the usage of dynamic models to manage data privacy efficiently. At the same time, some frameworks explore the application of advanced DL methodologies to detect and classify threats in diverse environments. These innovations enhance security, efficiency, and reliability in increasingly intrinsic networked systems. Despite crucial enhancements in intrusion detection and prevention systems, a notable research gap remains in incorporating diverse models to improve adaptability and scalability in real-time environments. Many existing models need help with resource constraints and need to maintain performance across varying data dispersions. This underscores the requirement for more holistic solutions that effectively address modern cyber threats’ complexities in dynamic settings.

Materials and methods

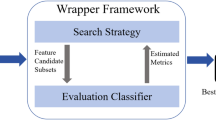

This manuscript presents a novel PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology. The primary purpose of the PPSLOA-HDBDE model is to leverage advanced optimization and ensemble techniques to ensure data confidentiality while maintaining analytical efficacy. It encompasses four processes involving data preprocessing, SCSO-based FS, ensemble classification models, and an IMPA-based parameter optimizer. Figure 2 portrays the entire flow of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology.

Data preprocessing: LSN

In the first stage, the PPSLOA-HDBDE model utilizes LSN to measure the input data. This normalization technique is specifically beneficial for algorithms sensitive to feature ranges, namely gradient-based approaches. By employing LSN, the model enhances convergence rates during training and improves overall performance, as it reduces the influence of outliers and scales the data to a uniform range. LSN is an ideal choice to implement and interpret compared to other normalization methodologies, making it an accessible option for practitioners. Its capacity to retain the associations between features while standardizing their scales additionally contributes to the accuracy and reliability of the model. Overall, LSN is a valuable preprocessing step that improves the effectiveness of the PPSLOA-HDBDE model in handling diverse datasets. LSN, also called min-max normalization, rescales features to a definite range, usually [0, 1]. This model certifies that every feature donates similarly to the study by removing the effects of opposing units and magnitudes. Converting the data linearly improves the performance of ML techniques, chiefly those delicate to feature measures, like gradient descent-based approaches. Linear scaling enhances the rate of convergence and complete accuracy of the model. This method is mainly valuable in high-dimensional databases, certifying that no feature excessively affects the outcomes.

FS using SCSO model

Besides, the SCSO-based FS process is applied to decrease the high dimensionality problem85. This model is chosen for its efficiency in handling high dimensionality, a common threat in ML techniques. SCSO replicates the hunting behaviour of sand cats, allowing it to effectually explore the feature space and detect the most relevant features while averting overfitting. Unlike conventional models, SCSO balances exploration and exploitation, producing a more robust FS. This adaptability makes it appropriate for intrinsic datasets where irrelevant or redundant features can affect the model’s performance. Furthermore, the SCSO approach underscores superior convergence speed related to other optimization methods, confirming quicker processing times (PTs) without sacrificing accuracy. Its innovative mechanism and proven efficacy make SCSO ideal for FS in IDSs. Figure 3 portrays the working flow of the SCSO model.

In the problem of dimension optimize\(\:d\), a \(\:SandCat\)is a \(\:1\times\:d\) array demonstrating the problem solving, described as \(\:Sand\)\(\:Ca{t}_{i}=\)\(\:\dots\:,{x}_{d};i\in\:population\left(1,n\right)\). All \(\:x\) should be among the lower and upper limits: \(\:\forall\:{x}_{i}\in\:\) [upper, lower]. If the SCSO model has been applied, it primarily makes a matrix of initialization \(\:\left({N}_{pop}\times\:{N}_{d}\right)\) based on the size of the difficulty. The fitness cost of every \(\:SandCat\) has been gained by calculating the clear fitness function (FF). If an iteration is accomplished, the \(\:SandCat\) is designated using the optimal cost still in that iteration. When no improved solution is initiated in the following iteration, keeping it in the memories is redundant.

Search for prey

The SCSO model uses SandCats’ auditory ability to detect lower frequencies. \(\:SandCats\) can observe lower frequency under 2 kHz. During this model, this search range has been described as \(\:{r}_{G}\). Based on the algorithmic working principle, these values will linearly reduce from 2 -\(\:0\) in the iteration process, slowly moving toward the prey without skipping or missing. The \(\:{S}_{m}\) pretends the sand cat’s auditory features are two using the statement. The mathematical reproduction is described in the following:

On the other hand, \(\:ite{r}_{c}\) represents the present iteration amount, and \(\:ite{r}_{Max}\) denotes maximal iteration.

The leading parameter that controls the conversion in the middle of the development and the exploration stage is \(\:R\). Owing to these adaptable strategies, the possibility and transition between the dual stages should be more stable. \(\:R\) is described as demonstrated:

To prevent dropping into a local best, every sand cat’s range of sensitivity has been changed, well-defined as:

During the SCSO model, the \(\:SandCat\) upgrades its position according to the best solution, its present position, and the range of sensitivity, looking for another possible optimal position of prey. This searching behaviour is delineated as follows:

\(\:Po{s}_{bc}\) represents the best candidate position, and \(\:Po{s}_{c}\) denotes the present position.

Attacking prey

If a \(\:SandCat\) attacks its prey, it initially utilizes the\(\:Po{s}_{b}\) ideal and \(\:Po{s}_{c}\)present positions to create a \(\:Po{s}_{rnd}\) randomly formed position. Assume that the \(\:SandCats\) range of circle sensitivity, to prevent dropping into the local optimal, the Roulette model has been applied to pick at random an angle for every \(\:SandCat\), such that the \(\:SandCat\) can tactic the searching position:

The attack and search stages from the SCSO Model are guaranteed by adaptability. \(\:{r}_{G}\) and \(\:R.\) This parameter permits SCSO to change effortlessly among the dual stages. If \(\:R\vee\:1,\) the \(\:SandCats\) hunt for prey; If \(\:R\vee\:\le\:1\), the \(\:SandCats\) attack prey. The pseudocode of the SCSO model is demonstrated in Algorithm 1.

The FF used in the SCSO technique is projected to balance the number of chosen features in every solution and the classifier accuracy gained by utilizing these preferred features. Equation (7) denotes the FF for estimating solutions.

Here, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{R}\left(D\right)\) signifies the classifier rate of error. \(\:\left|R\right|\) means the cardinality of the nominated sub-set, \(\:C\vee\:\) represents the total no. of features in the database, \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) signify the dual parameters equivalent to the significance of classifier quality and sub-set length. ∈ [1,0] and \(\:\beta\:=1-\alpha\:.\)

Ensemble classification models

Moreover, the recognition of intrusion detection is accomplished by using an ensemble of TCN, MAE, and XGBoost models. These methods are chosen for their complementary merits. TCN outperforms in capturing temporal patterns in data, making it ideal for detecting time-dependent attacks. MAE efficiently learns intrinsic feature representations, improving the technique’s capability to detect anomalies. XGBoost, known for its high performance in structured data, provides robust predictions with robust generalization capabilities. Integrating these models employs their advantages, enhancing accuracy and resilience against various attack types. Moreover, the ensemble approach mitigates the risk of overfitting and improves overall reliability, making it more significant than using any single model alone. This integrated strategy confirms a more comprehensive and effectual IDS.

TCN classifier

TCN is one of the new neural networks that depend upon the structure of CNN86. TCN utilizes structures like dilated causal convolution (DCC) and residual blocks. When equated to conventional CNN, DCC concentrates only on historical and present data without seeing prospect data. This indicates that the output value \(\:{y}_{t}\) at \(\:t\)-\(\:th\) time was formed only by the value of the input at a \(\:t\)-\(\:th\) time and former, up to input \(\:\left\{{x}_{0},{x}_{1},\ldots\:{x}_{t-1},{x}_{t}\right\}\). Conventional CNN upsurges the receptive area by including a pooling layer foremost in data loss. Unlike, TCN presents DCC to enlarge the receptive area, permitting it to take dependences through a higher range without misplacing data. The mathematical formulation is computed below:

Here, \(\:t\) signifies the sequence part index, \(\:p\) represents the dilation factor, \(\:{x}_{i}\in\:{R}^{n}\) denotes the sequence element, \(\:F\left(t\right)\) refers to a dilated convolution of element \(\:{x}_{t}\), and \(\:k\) denotes the dimension of the convolutional kernel. The residual connection inserts an input \(\:x\) to the output \(\:f\left(x\right)\). \(\:f\left(x\right)\) is stated below:

The extension of causal convolutional in TCN certifies that data flows precisely from the earlier to the future, thereby averting data leakage from the upcoming to the previous. Even with fewer layers, the DCC application permits TCN to hold a greater receptive area, permitting it to procedure lengthier time-series data. Besides, DCC includes methods like dropout regularization, weight normalization, and\(\:ReLU\) activation function. These models improve the model’s non-linear representation abilities and recover its constancy and generalization performance, eventually increasing its efficiency.

MAE classifier

MAE is a neural network that removes the unseen feature from input data87. The MAE architecture comprises two sections: a decoder and an encoder. The encoding and decoding part contains input and output layers with some fully connected (FC) layers. An FC layer has accompanied the ReLU or sigmoid. The FC layer handling from \(\:x\in\:{R}^{\varOmega\:}\) to \(\:y\in\:{R}^{\varPsi\:}\) is calculated as:

whereas \(\:\delta\:\left(\bullet\:\right)\) refers to the activation function, \(\:W\in\:{R}^{\varPsi\:\times\:\varOmega\:}\) represents the weighting coefficients matrix, and \(\:b\in\:{R}^{\varPsi\:}\) denotes the biased term.

In training, the auto-encoder reduces the loss function to discover the biases and optimum weighting coefficients. The function of loss is considered as follows:

Here, \(\:{x}_{i}\) represents the \(\:i‐th\) input neuron, and \(\:{z}_{i}\) signifies the equivalent output neuron of the auto-encoder; correspondingly, \(\:H\) stands for neuron counts in the input layer.

The network encoding part usually converts the data input into a low-dimensional space, and these lower-dimensional representations are applied to minimize the data input. Hence, the auto-encoder is a non-linear Karhunen-Loeve transform (KLT) form.

XGBoost classifier

XGBoost combines linear scale determination with a definite regression tree learning method88. The technique integrates architectures with decreased accuracy by employing specific approaches. The aim is to make a combined architecture that must be highly accurate. In the model training procedure, XGBoost improves the boosting method. All iterations produce an updated DT to fit the residuals created in the prior rounds. XGBoost could constantly increase its accuracy and generalization capacity with the iterative optimizer. But, conventional gradient boosting-DT (GBDT) techniques employ only 1st order derivative; XGBoost is a 2nd order Taylor extension of the loss function, tackles the complexity of the method by presenting regularization relationships for avoiding overfit issues as well and implements a highly refined estimation method while dividing nodes for significantly capturing the non-linear correlations among features. Figure 4 depicts the infrastructure of the XGBoost technique. This method is dependent upon the resulting mathematical values:

An incorporation model for the DT is represented as given below:

Here, \(\:{x}_{i}\) denotes the first \(\:i\) input feature; \(\:M\) represents the DT counts; F describes the tree collection space; \(\grave{y}_{i}\) denotes the predictable value.

XGBoost’s loss function is given as:

The primary portion of the operation is the predictable error among the evaluated values as well as actual training values of the XGBoost framework, and the secondary part signifies the intricacy of the tree that is mainly employed for controlling the regularization of the model complexity:

Where\(\:\tau\:\) and \(\:\gamma\:\) describe penalty factors.

In addition to an increment function \(\:{f}_{t}\left(X\right)\) to Eq. (14), the loss function value will be decreased. The \(\:t-th\) time is mentioned below:

The 2nd -order Taylor expansion of Eq. (16) has been utilized to estimate the primary function, and the set of instances in every branch of the \(\:j\) tree could be described as \(\:{I}_{j}=\left\{i|q\left({x}_{i}=j\right)\right)\). the \(\:{Q}_{\left(t\right)}\) could be represented,

Now, \(\:{g}_{i}={\partial\:}_{{\stackrel{\prime }{y}}_{i}^{t+1}}l\left({y}_{i},{\stackrel{\prime }{y}}_{i}^{t+1}\right)\), and \(\:{h}_{i}={\partial\:}_{{\stackrel{\prime }{y}}_{i}^{t+1}}^{2}l\left({y}_{i},{\stackrel{\prime }{y}}_{i}^{t+1}\right)\) denotes the loss function’s 1st and 2nd order derivative, respectively. Define \(\:{G}_{i}={\sum\:}_{}^{}i\in\:{I}_{j}{g}_{i},{H}_{i}={\sum\:}_{i\in\:{I}_{j}}^{}{h}_{i}\):

The partial derivative of \(\:\omega\:\) yields

By integrating weights to the main function as given below,

Parameter optimizer: IMPA

Finally, the hyperparameter tuning of three models is performed using an IMPA technique89. This method is chosen for its efficiency in navigating intrinsic optimization landscapes. IMPA replicates the foraging behaviour of marine predators, allowing it to efficiently balance exploration and exploitation during the tuning process. This results in a more thorough search for optimum hyperparameter settings related to conventional techniques, which may converge prematurely. The model’s adaptability makes it appropriate for high-dimensional parameter spaces commonly found in ML approaches. Furthermore, IMPA has achieved excellent performance using convergence speed and solution quality, outperforming other optimization models such as grid or random search. Overall, the usage of IMPA improves the performance of the model by confirming that hyperparameters are finely tuned, resulting in improved predictive accuracy and robustness in intrusion detection tasks. Figure 5 depicts the structure of the IMPA model.

The main feature of MPA is using the social behaviour of marine animals to efficiently balance exploitation and exploration. Both prey and predators are considered searching individuals for prey and hunting for food. The MPA first generates a randomly generated population by describing the lower and upper bounds, and the initialization process is exposed in Eq. (20).

The \(\:Prey\) matrix presents the location vector.

whereas \(\:m\) denotes a population dimension; \(\:n\) refers to the location of every dimension. The \(\:Elite\) matrix depends upon the victim’s fitness assessment, choosing the finest individual as the hunter vector and repeating it \(\:n\) times to generate the \(\:Elite\).

The MPA is separated into 3 stages dependent upon the victim and predator speed ratio, each equivalent to dissimilar iterative procedures.

Stage 1: This stage is called an exploration phase. It happens in the 1st 1/3 of the iteration procedure. The prey is uniformly spread all over the exploration area in the early iteration, and the distance between the prey and predator will be moderately great; Brownian motion simplifies fast survey of the target’s location. The mathematic formulation is mentioned below:

Here, \(\:{\overrightarrow{R}}_{B}\) means a vector of randomly produced values by Brownian motion that follows a Gaussian distribution. \(\:{\overrightarrow{S}}_{i}\) denotes a step size. The constant value \(\:P\) is set as \(\:5\), and \(\:\overrightarrow{R}\) refers to a randomly generated vector uniformly distributed among \(\:0\) and 1.

Stage 2: This stage aims to attain a competitive changeover from the exploration to exploitation stages, which arise between \(\:1/3\) and \(\:2/3\) of the iterative method. The individuals are divided into dual equivalent parts, and one portion is upgraded depending upon Eqs. (25) and (26).

Here, \(\:{\overrightarrow{R}}_{L}\) denotes a vector of randomly produced values by Levy motion. The remaining part of the population is upgraded depending upon Eqs. (27) and (28).

Whereas \(\:CF\) denotes an adaptive control parameter that is definite as:

The variable \(\:Iter\) specifies the present count of iterations, whereas \(\:{Max}_{Iter}\) signifies the maximum iteration count. In the second stage, exploitation and exploration operations happen simultaneously as the hunter and victim technique each other, with a decreased step size compared to the preceding stage.

Stage 3 happens in the previous \(\:1/3\)th of the iterative procedure. The hunters start changing from Brownian to Levy motions using the upgrading formulation mentioned below.

Then, there are Eddy Formation and Fish Aggregating Device (FAD) effects in the real predator method, and FAD is considered a local goal. So, these cases want to pretend in the iterative procedure to avoid dropping into local goals. The depiction of FADs is given below:

The FAD constant value is fixed as 2. \(\:r\in\:\left(\text{0,1}\right).\overrightarrow{U}\), which means a dual vector, with every element described in Eq. (33). The norm of marine memory storage is parallel to the greedy tactic, which equates the outcomes beforehand and after the iteration and only recollects the solution with superior fitness. Its calculation is mentioned below:

Meanwhile, \(\:{X}_{i}^{t+1}\) signifies the location of the optimum candidate solution taken by an \(\:ith\) individual after the \(\:\left(t+1\right)th\) iteration. \(\:f\) indicates the FF.

A new MPA separates optimizer iterations into 3 distinct stages. The 1st stage concentrates on exploration, the 2nd changeovers from exploration to exploitation, and the 3rd is only for exploitation. This tactic permits every stage to focus on dissimilar tasks, improving the exploration ability. If the early matrix quality is lower, then it will gradually converge. Also, transferring among dissimilar stages might present transition costs. For instance, certifying the effectual transfer of outcomes without data loss is vital when transitioning from the global to local search phases.

Opposition-based learning (OBL) is an enhanced optimizer tactic in searching. Its main thought is to produce an opposite solution and use it for the optimizer procedure. The IMPA is demonstrated in Eq. (35) to incorporate the OBL technique into the initialize and FF computation phases.

-

Initialize stage: Employ Eq. (35) to produce the opposite initialize matrix of Prey, intensifying individuals’ distribution range within matrix form. The enhanced tactic upsurges the likelihood of an initial result covering the optimum solution, increases the range and excellence of the early matrix, and quickens convergence speed.

-

FF computation stage: Throughout the optimizer procedure, the FF is computed at the end of every iteration to discover and maintain the optimum solution. Conversely, owing to a stochastic method, the calculated fitness value might vary considerably from the real optimum solution. Then, this enhanced plan uses Eq. (20) to produce an opposite result of equivalent extent to the present individual result after every iteration.

Fitness choices significantly influence the efficiency of IMPA. The hyperparameter range method encompasses the encoded method for considering the effectiveness of candidate results. The IMPA reflects accuracy as the primary standard for projecting the FF in this work.

Here, \(\:TP\) and \(\:FP\) denote true and false positive values, respectively.

Experimental validation

The performance evaluation of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology is studied under the BoT-IoT dataset90. The database comprises 2056 samples under five classes, as represented in Table 1. The BoT-IoT dataset was developed in the Cyber Range Lab of UNSW Canberra, simulating a realistic network environment that integrates normal and botnet traffic. It encompasses diverse source files, comprising original pcap files, generated argus files, and CSV files, all organized by attack category and subcategory to ease labelling. The captured pcap files total 69.3 GB, containing over 72 million records, while the extracted flow traffic in CSV format is 16.7 GB. The dataset features a range of attacks, including DDoS, DoS, OS and Service Scan, Keylogging, and Data Exfiltration, with DDoS and DoS attacks also classified by protocol. To streamline dataset handling, a 5% sample was extracted using MySQL queries, resulting in four files totalling approximately 1.07 GB and containing about 3 million records. The suggested technique is simulated using the Python 3.6.5 tool on PC i5-8600k, 250GB SSD, GeForce 1050Ti 4GB, 16GB RAM, and 1 TB HDD. The parameter settings are provided: learning rate: 0.01, activation: ReLU, epoch count: 50, dropout: 0.5, and batch size: 5.

Figure 6 determines the confusion matrices produced by the PPSLOA-HDBDE model over different epochs. The results state that the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique precisely has effectual identification and recognition of all 5 class labels.

The intrusion detection result of the PPSLOA-HDBDE method is identified under dissimilar epochs in Table 2; Fig. 7. The table values indicate that the PPSLOA-HDBDE method appropriately identified all the samples. On 500 epoch counts, the PPSLOA-HDBDE method offers an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.89%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.43%,\(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.64%, \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 96.53%, and MCC of 95.82%. Also, on 1000 epoch counts, the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology offers an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.11%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.76%,\(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.72%, \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 97.22%, and MCC of 96.66%. Furthermore, on 2000 epochs, the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology provides an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.47%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 93.37%,\(\:\mathfrak{R}c{a}_{l}\) of 89.85%, \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 91.33%, and MCC of 89.85%. Eventually, on 3000 epochs, the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology delivers an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 96.96%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 92.90%,\(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 84.95%, \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 87.38%, and MCC of 86.25%.

Figure 8 shows the training \(\:acc{u}_{y}\)(TRAAC) and validation \(\:acc{u}_{y}\)(VLAAC) outcomes of the PPSLOA-HDBDE method under different epochs. The \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) values are estimated for 0-3000 epoch counts. The figure underlined that the TRAAC and VLAAC values display an increasing trend, which reported the capability of the PPSLOA-HDBDE method to have enhanced performance over various iterations. Furthermore, the TRAAC and VLAAC remain adjacent over epochs, which specifies lower minimum overfitting and shows superior performances of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique, promising constant prediction on unnoticed samples.

Figure 9 shows the TRA loss (TRALS) and VLA loss (VLALS) graph of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique under different epochs. The loss values are estimated for 0-3000 epoch counts. The TRALS and VLALS curves indicate a decreasing trend, reporting the proficiency of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology in balancing a trade-off between generalized and data fitting. The constant reduction in loss values furthermore possibilities the more outstanding performances of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology and tuning of the predictive outcomes over time.

In Fig. 10, the precision-recall (PR) curve analysis of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique under different epochs interprets its performances by plotting Precision against Recall for all 5 class labels. The figure demonstrates that the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique consistently achieves improved PR values across various classes, indicating its ability to maintain high precision and recall by balancing true positive predictions with actual positives. The constant increase in PR results between all 5 class labels represents the effectiveness of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology in the classification procedure.

In Fig. 11, the ROC curve of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique under different epochs is examined. The outcomes denote that the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique attains superior ROC results over every class, representing the vital ability to discriminate the class labels. This consistent tendency of better ROC values over several class labels indicates the efficient performances of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology in predicting class labels, emphasizing the robust nature of the classifier process.

The comparison of the PPSLOA-HDBDE approach with current methods is demonstrated in Table 3; Fig. 1291,92,93. Regarding \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology has a greater \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.49%. In contrast, the AROMA, Dynamic Bandwidth Allocation(DBA), SOM-SVM, CNN-BiLSTM, CANET, RFS-1, CNN-Focal, Dense Convolutional Network with Discrete Wavelet Transform (DenseNet-DWT), Linear Discriminant Analysis with Discrete Cosine Transform (LDA-DCT), and Robust Linked List with Steganography Without Embedding(RLL-SWE) models have lower \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 95.02%, 96.99%, 96.12%, 99.15%, 98.85%, 98.51%, 98.32%, 96.11%, 97.68%, and 95.51%, correspondingly. Also, for \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique has a greater \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.74%, whereas the AROMA, DBA, SOM-SVM, CNN-BiLSTM, CANET, RFS-1, CNN-Focal, DenseNet-DWT, LDA-DCT, and RLL-SWE techniques have lower \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 95.69%, 95.00%, 91.18%, 96.89%, 97.12%, 97.65%, 96.81%, 96.04%, 96.89%, and 95.86%, correspondingly. Finally, for the \(\:{F1}_{score}\), the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique has a better \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 98.52%, while the AROMA, DBA, SOM-SVM, CNN-BiLSTM, CANET, RFS-1, CNN-Focal, DenseNet-DWT, LDA-DCT, and RLL-SWE models have minimum \(\:{F1}_{score}\) of 93.97%, 95.12%, 94.27%, 96.68%, 98.00%, 97.89%, 96.99%, 96.39%, 94.13%, and 95.56%, respectively. The table values indicated that the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique outperformed existing models.

Table 4; Fig. 13 state the comparative outcomes of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology based on PT. The result indicates that the PPSLOA-HDBDE model achieved superior performance. In terms of PT, the PPSLOA-HDBDE model offers a lower PT of 8.48s, while the AROMA, DBA, SOM-SVM, CNN-BiLSTM, CANET, RFS-1, CNN-Focal, DenseNet-DWT, LDA-DCT, and RLL-SWE models attain improved PT values of 17.84s, 16.09s, 13.41s, 15.10s, 14.20s, 15.27s, 16.63s, 14.99s, 16.23s, and 15.02s, correspondingly.

Conclusion

In this manuscript, a novel PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology is presented. The primary purpose of the PPSLOA-HDBDE methodology is to utilize advanced optimization and ensemble techniques to ensure data confidentiality while maintaining analytical efficacy. It encompasses four processes involving data preprocessing, SCSO-based FS, ensemble classification models, and IMPA-based parameter optimizer. At the primary stage, LSN is utilized to scale the input data. Besides, the SCSO-based FS process is employed to diminish the high dimensionality problem. Moreover, intrusion detection recognition is performed using an ensemble of TCN, MAE, and XGBoost classifiers. Lastly, the three models’ hyperparameter tuning is accomplished using an IMPA model. An extensive range of experimentations is performed to improve the performance of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique, and the outcomes are examined using distinct measures. The performance validation of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique illustrated a superior accuracy value of 99.49% over existing models. The limitations of the PPSLOA-HDBDE technique comprise potential threats in data heterogeneity across diverse devices, which may affect the accuracy of the FL results. Furthermore, the computational overhead associated with real-time sentiment analysis can strain resource-constrained edge devices. Privacy concerns regarding data sharing, even in a federated setting, remain a critical issue. Future studies may explore advanced privacy-preserving models to improve data safety further. Moreover, investigating adaptive mechanisms to optimize model training depending on varying device capabilities and network conditions would be beneficial. Expanding the model’s applicability to diverse domains beyond consumer electronics could also give broader insights into its efficiency. Lastly, incorporating user feedback into the recommendation process could enhance personalization and user satisfaction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vigneshvenkateswaran/bot-iot.

References

Hazman, C., Guezzaz, A., Benkirane, S. & Azrour, M. Toward an intrusion detection model for IoT-based smart environments. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83 (22), 62159–62180 (2024).

AbdelMouty, A. M. An advanced optimization technique for integrating IoT and Cloud computing on manufacturing performance for supply chain management. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things, 7(2). (2022).

Sadia, H. et al. Intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks: A machine learning based Approach. IEEE Access. (2024).

Rajawat, A. S., Goyal, S. B., Bedi, P., Kautish, S. & Shrivastava, D. P. Analysis assaulting pattern for the security problem monitoring in 5G-enabled sensor network systems with big data environment using artificial intelligence/machine learning. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. (2023).

Varastan, B., Jamali, S. & Fotohi, R. Hardening of the internet of things by using an intrusion detection system based on deep learning. Cluster Comput. 27 (3), 2465–2488 (2024).

Kathirvel, A. & Maheswaran, C. P. Enhanced AI-Based intrusion detection and response system for WSN. In Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems 155–177 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023).

Indra, G., Nirmala, E., Nirmala, G. & Senthilvel, P. G. An ensemble learning approach for intrusion detection in IoT-based smart cities. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl., pp.1–17. (2024).

Kaushik, A. & Al-Raweshidy, H. A novel intrusion detection system for internet of things devices and data. Wirel. Netw. 30 (1), 285–294 (2024).

Shah, H. et al. Deep learning-based malicious smart contract and intrusion detection system for IoT environment. Mathematics, 11(2), 418. (2023).

Sai, N. R., Kumar, G. S. C., Kumar, D. L. S., Praveen, S. P. & Bikku, T. Enhancing intrusion detection in IoT-Based vulnerable environments using federated learning. In Big data and edge intelligence for enhanced cyber defense 103–126 (CRC, 2024).

Haseeb, K. et al. AI assisted energy optimized sustainable model for secured routing in mobile wireless sensor network. Mobile Netw. Appl., pp.1–9. (2024).

Aruchamy, P., Gnanaselvi, S., Sowndarya, D. & Naveenkumar, P. An artificial intelligence approach for energy-aware intrusion detection and secure routing in internet of things‐enabled wireless sensor networks. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp.. 35 (23), e7818 (2023).

Ntizikira, E., Wang, L., Chen, J. & Saleem, K. Honey-block: Edge assisted ensemble learning model for intrusion detection and prevention using defense mechanism in IoT. Comput. Commun. 214, 1–17 (2024).

Kipongo, J., Swart, T. G. & Esenogho, E. Artificial intelligence-based intrusion detection and prevention in edge-assisted SDWSN with modified honeycomb structure. IEEE Access. (2023).

Abdusalomov, A., Kilichev, D., Nasimov, R., Rakhmatullayev, I. & Cho, I. Y., Optimizing smart home intrusion detection with harmony-enhanced extra trees. IEEE Access. (2024).

Shitharth, S., Mohammed, G. B., Ramasamy, J. & Srivel, R. Intelligent intrusion detection algorithm based on multi-attack for edge-assisted internet of things. In Security and risk analysis for intelligent edge computing 119–135 (Springer, 2023).

Sajid, M. et al. Enhancing intrusion detection: A hybrid machine and deep learning approach. J. Cloud Comput., 13(1), 123. (2024).

Salama, R. & Ragab, M. Blockchain with explainable artificial intelligence driven intrusion detection for clustered IoT driven ubiquitous computing system. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng., 46(3). (2023).

Vakili, A. et al. A new service composition method in the cloud‐based internet of things environment using a grey wolf optimization algorithm and MapReduce framework. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 36 (16), e8091 (2024).

Ntizikira, E., Lei, W., Alblehai, F., Saleem, K. & Lodhi, M. A. Secure and privacy-preserving intrusion detection and prevention in the internet of unmanned aerial vehicles. Sensors, 23(19), 8077. (2023).

Heidari, A., Shishehlou, H., Darbandi, M., Navimipour, N. J. & Yalcin, S. A reliable method for data aggregation on the industrial internet of things using a hybrid optimization algorithm and density correlation degree. Cluster Comput., pp. 1–19. (2024).

Heidari, A., Navimipour, N. J. & Unal, M. A secure intrusion detection platform using blockchain and radial basis function neural networks for internet of drones. IEEE Internet Things J. 10 (10), 8445–8454 (2023).

Heidari, A., Amiri, Z., Jamali, M. A. J. & Jafari, N. Assessment of reliability and availability of wireless sensor networks in industrial applications by considering permanent faults. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp., p.e8252. (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. A lightweight intrusion detection method for IoT based on deep learning and dynamic quantization. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9, e1569 (2023).

Zanbouri, K. et al. A GSO-based multi‐objective technique for performance optimization of blockchain‐based industrial internet of things. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 37 (15), e5886 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. A multi-agent deep-reinforcement-learning-based strategy for safe distributed energy resource scheduling in energy hubs. Electronics, 12(23), 4763. (2023).

Amiri, Z., Heidari, A. & Navimipour, N. J. Comprehensive survey of artificial intelligence techniques and strategies for climate change mitigation. Energy, 132827. (2024).

Devi, R. A. & Arunachalam, A. R. Enhancement of IoT device security using an improved elliptic curve cryptography algorithm and malware detection utilizing deep LSTM. High-Confid. Comput., 3(2), p.100117. (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Qian, H., Gao, Y. & Wang, Q. June. A high-dimensional temporal data publishing method based on dynamic bayesian networks and differential privacy. In 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. (2024).

Younis, R., Ahmadi, Z., Hakmeh, A. & Fisichella, M. August. Flames2graph: An interpretable federated multivariate time series classification framework. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 3140–3150). (2023).

Zhao, Z., Liang, X., Huang, H. & Wang, K. Deep federated learning hybrid optimization model based on encrypted aligned data. Pattern Recognit., 148, 110193. (2024).

Chougule, A., Chamola, V., Hassija, V., Gupta, P. & Yu, F. R. A novel framework for traffic congestion management at intersections using federated learning and vertical partitioning. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70 (1), 1725–1735 (2023).

El-Adawi, E., Essa, E., Handosa, M. & Elmougy, S. Wireless body area sensor networks based on human activity recognition using deep learning. Sci. Rep., 14(1), 2702. (2024).

Zainudin, A., Akter, R., Kim, D. S. & Lee, J. M. Federated learning inspired low-complexity intrusion detection and classification technique for sdn-based industrial cps. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. (2023).

Bushra, S. N., Subramanian, N., Shobana, G. & Radhika, S. A novel Jarratt butterfly Ebola optimization-based attentional random forest for data anonymization in cloud environment. J. Supercomput.. 80 (5), 5950–5978 (2024).

Hou, W. et al. Adaptive training and aggregation for federated learning in multi-tier computing networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 23 (5), 4376–4388 (2023).

Jiang, W., Han, H., Zhang, Y., Mu, J. & Shankar, A. Intrusion detection with federated learning and conditional generative adversarial network in satellite-terrestrial integrated networks. Mobile Netw. Appl., pp. 1–14. (2024).

Feng, K. Y. et al. Model sparsification for communication-efficient multi-party learning via contrastive distillation in image classification. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 8 (1), 150–163 (2023).

Abdallah, A. et al. Cloud network anomaly detection using machine and deep learning techniques-recent research advancements. IEEE Access. (2024).

Shan, Y. et al. CFL-IDS: An effective clustered federated learning framework for industrial internet of things Intrusion detection. IEEE Internet Things J. (2023).

Babu, E. S., Barthwal, A. & Kaluri, R. Sec-edge: Trusted blockchain system for enabling the identification and authentication of edge based 5G networks. Comput. Commun. 199, 10–29 (2023).

Begum, M. B. et al. An efficient and secure compression technique for data protection using burrows-wheeler transform algorithm. Heliyon, 9(6). (2023).

Babu, E. S., Rao, M. S., Swain, G., Nikhath, A. K. & Kaluri, R. Fog-Sec: Secure end‐to‐end communication in fog‐enabled IoT network using permissioned blockchain system. Int. J. Network Manag. 33 (5), e2248 (2023).

Devarajan, G. G., Nagarajan, S. M., Daniel, A., Vignesh, T. & Kaluri, R. Consumer product recommendation system using adapted PSO with federated learning method. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. (2023).

Yenduri, G. et al. Blockchain for handling the data in higher education. In Applied Assistive Technologies and Informatics for Students with Disabilities 1–16 (Springer, 2024).

Hao, Y., Kumari, S., Lakshmanna, K. & Chen, C. M. Privileged insider attacks on two authentication schemes. In Advances in Smart Vehicular Technology, Transportation, Communication and Applications: Proceedings of VTCA 2022 515–524 (Springer, 2023).

Saheed, Y. K., Usman, A. A., Sukat, F. D. & Abdulrahman, M. A novel hybrid autoencoder and modified particle swarm optimization feature selection for intrusion detection in the internet of things network. Front. Comput. Sci., 5, 997159. (2023).

Saheed, Y. K., Abdulganiyu, O. H. & Tchakoucht, T. A. Modified genetic algorithm and fine-tuned long short-term memory network for intrusion detection in the internet of things networks with edge capabilities. Appl. Soft Comput., 155, p.111434. (2024).

Saheed, Y. K., Omole, A. I. & Sabit, M. O. GA-mADAM-IIoT: A new lightweight threats detection in the industrial IoT via genetic algorithm with attention mechanism and LSTM on multivariate time series sensor data. Sensors Int., 6, 100297. (2025).

Heidari, A., Jafari Navimipour, N., Dag, H. & Unal, M. Deepfake detection using deep learning methods: A systematic and comprehensive review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 14 (2), e1520 (2024).

Heidari, A., Navimipour, N. J., Dag, H., Talebi, S. & Unal, M. A novel blockchain-based deepfake detection method using federated and deep learning models. Cogn. Comput., pp.1–19. (2024).

Boopathi, M. et al. Optimization algorithms in security and privacy-preserving data disturbance for collaborative edge computing social IoT deep learning architectures. Soft. Comput., pp. 1–13. (2023).

Heidari, A., Navimipour, N. J. & Otsuki, A. Cloud-based non-destructive characterization. Non-destructive material characterization methods, pp. 727–765. (2024).

Asadi, M., Jamali, M. A. J., Heidari, A. & Navimipour, N. J. Botnets unveiled: A comprehensive survey on evolving threats and defense strategies. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 35 (11), e5056 (2024).

Ramkumar, J., Vadivel, R., Narasimhan, B., Boopalan, S. & Surendren, B. March. Gallant Ant Colony Optimized Machine Learning Framework (GACO-MLF) for Quality of Service Enhancement in Internet of Things-Based Public Cloud Networking. In International Conference on Data Science and Communication 425–438 (Springer, 2023).

Heidari, A., Jamali, M. A. J. & Navimipour, N. J. Fuzzy logic multicriteria decision-making for broadcast storm resolution in vehicular ad hoc networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst., p.e6034. (2024).

Saini, H. et al. Enhancing cloud network security with a trust-based service mechanism using k-anonymity and statistical machine learning approach. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl., pp.1–26. (2024).

Dansana, J., Kabat, M. R. & Pattnaik, P. K. Improved 3D rotation-based geometric data perturbation based on medical data preservation in big data. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., 14(5). (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Tang, M. VPPLR: Privacy-preserving logistic regression on vertically partitioned data using vectorization sharing. J. Inf. Secur. Appl., 82, p.103725. (2024).

Jadhav, P. S. & Borkar, G. M. Optimal key generation for privacy preservation in big data applications based on the marine predator whale optimization algorithm. Ann. Data Sci., pp. 1–31. (2024).

Vasa, J. & Thakkar, A. Deep learning: Differential privacy preservation in the era of big data. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 63 (3), 608–631 (2023).

Jahin, M. A., Shovon, M. S. H., Shin, J., Ridoy, I. A. & Mridha, M. F. Big data—supply chain management framework for forecasting: Data preprocessing and machine learning techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng., pp.1–27. (2024).

Bajpai, A., Verma, H. & Yadav, A. Optimizing data aggregation and clustering in internet of things networks using principal component analysis and Q-learning. Data Sci. Manag. 7 (3), 189–196 (2024).

Song, D. et al. Intrusion detection model using gene expression programming to optimize parameters of convolutional neural network for energy internet. Appl. Soft Comput., 134, p.109960. (2023).

Chen, S. & Huang, Y. A privacy-preserving federated learning approach for airline upgrade optimization. J. Air Transp. Manag., 122, p. 102693. (2025).

Dodda, S., Kumar, A., Kamuni, N. & Ayyalasomayajula, M. M. T. May. Exploring strategies for privacy-preserving machine learning in distributed environments. In 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence For Internet of Things (AIIoT) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024).

Kamatchi, K. & Uma, E. Securing the edge: Privacy-preserving federated learning for insider threats in IoT networks. J. Supercomput.. 81 (1), 1–49 (2025).

Dhavamani, L., Ananthavadivel, D., Akilandeswari, P. & Nanajappan, M. Differential privacy-preserving IoT data sharing through enhanced PSO. J. Comput. Inform. Syst., pp. 1–17. (2024).

Xia, J., Wu, M. & Li, P. SFML: A personalized, efficient, and privacy-preserving collaborative traffic classification architecture based on split learning and mutual learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst., 162, p.107487. (2025).

Liu, C., Li, J. & Sun, Y. Deep learning-based privacy-preserving publishing method for location big data in vehicular networks. J. Signal. Process. Syst., pp. 1–14. (2024).

Chowa, S. S. et al. An automated privacy-preserving self-supervised classification of COVID-19 from lung CT scan images minimizing the requirements of large data annotation. Sci. Rep., 15(1), p. 226. (2025).

Huang, X. et al. Accelerating privacy-preserving machine learning with GeniBatch. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth European Conference on Computer Systems (pp. 489–504). (2024).

Hossain, S., Senouci, S. M., Brik, B. & Boualouache, A. A privacy-preserving self-supervised learning-based intrusion detection system for 5G-V2X networks. Ad Hoc Netw., 166, p. 103674. (2025).

Bezanjani, B. R., Ghafouri, S. H. & Gholamrezaei, R. Fusion of machine learning and blockchain-based privacy-preserving approach for healthcare data in the internet of things. J. Supercomput.. 80 (17), 24975–25003 (2024).

Deebak, B. D. & Hwang, S. O. Privacy-preserving learning model using lightweight encryption for visual sensing Industrial IoT devices. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. (2025).

Zhou, J. et al. PPML-Omics: A privacy-preserving federated machine learning method protects patients’ privacy in omic data. Sci. Adv., 10(5), eadh8601. (2024).

Babu, C. S., AV, G. M., Lokesh, S., Niranjan, A. K. & Manivannan, Y. Unleashing IoT data insights: Data mining and machine learning techniques for scalable modeling and efficient management of IoT. In Scalable Modeling and Efficient Management of IoT Applications (153–188). IGI Global. (2025).

Li, H., Li, S. & Min, G. Lightweight privacy-preserving predictive maintenance in 6G enabled IIoT. J. Ind. Inf. Integr., 39, p. 100548. (2024).

Li, M., Zhu, Y., Du, R. & Jia, C. LPCR-IoT: Lightweight and privacy-preserving cross-modal Retrieval in IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. (2025).

Yang, W. et al. Privacy-preserving machine learning in cloud-edge-end collaborative environments. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Mumtaz, M., Tayyab, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Muzammal, S. M. & Hameed, K. Privacy preserving data analysis with generative AI. In AI Techniques for Securing Medical and Business Practices 391–410 (IGI Global, 2025).

Keerthana, P., Kavitha, M. & Subburaj, J. Privacy preservation in federated learning. In Federated Learning 127–144 (CRC, 2025).

Zhang, C. et al. SensFL: Privacy-preserving vertical federated learning with sensitive regularization. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci., 142(1). (2025).

Iam-On, N., Boongoen, T., Naik, N. & Yang, L. Leveraging ensemble clustering for privacy-preserving data fusion: Analysis of big social-media data in tourism. Inf. Sci., 686, 121336. (2025).

Sun, Z., Yang, Q., Liu, J., Zhang, X. & Sun, Z. A path planning method based on hybrid sand cat swarm optimization algorithm of green multimodal transportation. Appl. Sci., 14(17), 8024. (2024).

Yang, M. et al. A short-term power load forecasting method based on SBOA–SVMD-TCN–BiLSTM. Electronics, 13(17), p. 3441. (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. A novel asymmetrical autoencoder with a sparsifying discrete cosine stockwell transform layer for gearbox sensor data compression. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., 127, p. 107322. (2024).

Feng, M., Duan, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, J. & Ma, L. Carbon price prediction based on decomposition technique and extreme gradient boosting optimized by the grey wolf optimizer algorithm. Sci. Rep., 13(1), p. 18447. (2023).

Zhang, H., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Ge, Y. & Wang, L. MPPT control of photovoltaic array based on improved marine predator algorithm under complex solar irradiance conditions. Sci. Rep., 14(1), p. 19745. (2024).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vigneshvenkateswaran/bot-iot

Rao, G. S. et al. DDoSNet: Detection and prediction of DDoS attacks from realistic multidimensional dataset in IoT network environment. Egypt. Inf. J., 27, p. 100526. (2024).

Xu, B., Sun, L., Mao, X., Ding, R. & Liu, C. IoT intrusion detection system based on machine learning. Electronics, 12(20), p. 4289. (2023).

Zhao, P. et al. RLL-SWE: A robust linked list steganography without embedding for intelligence networks in smart environments. J. Netw. Comput. Appl., 234, p. 104053. (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/243/45. Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R319), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2903-02. The Author would also like to thank Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST), and GUST Engineering and Applied Innovation Research Center (GEAR), for supporting this project. The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatma S. Alrayes: Conceptualization, methodology development, experiment, formal analysis, investigation, writing. Mohammed Maray: Formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing. Asma Alshuhail: Formal analysis, review and editing. Khaled Mohamad Almustafa : Methodology, investigation. Ali M. Al-Sharafi: Review and editing.Shoayee Dlaim Alotaibi: Discussion, review and editing. Abdulbasit A. Darem: Conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, supervision, review and editing.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article contains no studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alrayes, F.S., Maray, M., Alshuhail, A. et al. Privacy-preserving approach for IoT networks using statistical learning with optimization algorithm on high-dimensional big data environment. Sci Rep 15, 3338 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87454-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87454-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Artificial intelligence-driven cybersecurity: enhancing malicious domain detection using attention-based deep learning model with optimization algorithms

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

End-to-end deep learning for smart maritime threat detection: an AE–CNN–LSTM-based approach

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

An efficient intrusion detection method based on Rime-NeoEvo Optimizer algorithm

Cluster Computing (2025)