Abstract

It is well recognised that endothermic processes such as dehydration and partial melting have the potential to exert measurable effects on the maximum temperatures reached in metamorphic rock systems. We show migmatitic metapelitic and mafic granulites record temperatures of ~ 820 °C, while spatially associated refractory Mg–Al-rich granulites record temperatures between 865 °C and > 920 °C. These thermally contrasting samples are separated by ~ 1500 m, with no apparent intervening faults or shear zones to explain the apparent difference in peak metamorphic conditions. Temperature versus enthalpy modelling of these samples along simple prograde P–T paths imply migmatisation slows the rate of temperature increase relative to rocks that do not melt. We speculate refractory rocks in the present study are created through early hydrothermal alteration and metamorphism, resulting in melt-resistant bulk compositions. There are many potential geological contexts where neighbouring rocks may have contrasting melt fertility; the deposition of a cover sequence, pre-metamorphic alteration, and the intrusion of igneous protoliths are all possibilities. With this in mind, variations in maximum modelled temperatures in granulite facies domains should be relatively common.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamorphism is the direct response and transformation of rocks to changes in their physical and chemical environment, primarily pressure and temperature. Typically, the temperatures recorded by mineral assemblages are assumed to be directly proportional to the heat flow through the rock volume, where variations in temperature are interpreted to reflect differences in heat flow. Although temperature change recorded by mineral assemblages is the direct record of energy input, the energy requirements associated with mineral reactions – both endothermic and exothermic – mean that mineral reactions potentially influence the rate of temperature change even when there is no change to the externally applied heat flow1,2,3,4,5,6. Melt crystallisation and the progress of hydration reactions are known to influence the rate of cooling in metamorphic rocks e.g5,7. However, processes associated with prograde metamorphism may have the most significant thermodynamic control over rates of temperature change. Sub-solidus dehydration and supra-solidus melting occur when the rock still has a high molar proportion of volatiles, relative to retrograde metamorphism where the system has lost a significant amount of fluid and melt.

In fertile bulk compositions that are prone to partial melting, the rate of temperature rise will slow until the reaction has run to completion e.g4,5. Therefore, temperature rise in fertile rocks can be inhibited relative to refractory rocks in the same thermal regime that are not melt fertile1,2,3,4,5. Indeed, there are many examples of rocks apparently ‘stalling’ their thermal evolution, where peak conditions have been constrained by mineral assemblages located directly above the solidus e.g8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. In these scenarios, it could be speculated that insufficient energy was available for the system to overcome the hurdle associated with thermal buffering. Correspondingly, many (U)HT terranes have been identified through mineral equilibria forward modelling of refractory rock types17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

Thermal buffering has been demonstrated experimentally and numerically2,4,5,24,25, as well as argued for in a number of case studies from geological terrains3,26,27,28. Most recently, apparent temperature disparities of 60–70 °C associated with spatial length scales ranging from tens to hundreds of metres in the Namaqua-Natal Metamorphic Complex have been suggested to reflect thermal buffering3. More generally, Diener and Macey28 interpreted regional-scale, temperature differences in the order of 25 °C to also reflect variations in the intensity of thermal buffering associated with melting, suggesting the thermal character of metamorphic terrains may in part reflect the thermodynamic demands of mineral reactions. However, at a regional scale, modest temperature variations could also simply reflect variations in heat flow, diachroneity in the development of mineral assemblages, or structural offsets. Notably, the absence of obvious evidence for structural discontinuities does not mean they do not exist, and metapelites in particular can respond to deformation subtly, meaning that structural dislocations can be hard to recognise e.g29. This could feasibly lead to the juxtaposition of thermally contrasting mineral assemblages. In order to demonstrate the potential magnitudes of temperature variation that could arise from thermal buffering, ideally thermal comparison needs to be made between rocks that are: (1) broadly similar in composition; (2) relatively close to each other; (3) part of a metamorphic system with a duration that allows the different rates of temperature change to result in recordable temperature disparity; and (4) not be separated by obvious structural boundaries. Additionally, the comparatively unbuffered rock composition cannot be completely or substantially enclosed – and therefore thermally isolated within the thermally buffered rock composition—and should be large enough in scale to respond to the external heat flow field.

In this study, we present contrasting temperature estimates from adjacent metasedimentary lithologies in the Warumpi Province, central Australia. These rocks have compositional variations which resulted in contrasting records of anatexis, presenting a potential natural laboratory to investigate the consequences of thermal buffering. Mg–Al-rich rocks record HT-UHT conditions and underwent little to no partial melting as evidenced by the lack of leucosomes, felsic segregations, veins, or even any appreciable feldspar. In contrast, adjoining migmatitic rocks that experienced voluminous partial melting record lower temperatures. Despite this perceived temperature discrepancy, these rocks are spatially close, have similar barometric character, and all experienced metamorphism during the Musgrave Orogeny. The contrast in apparent maximum temperature and record of partial melting between the neighbouring lithologies suggests melting-induced thermal buffering may have played an important role in their thermal evolution. More broadly, these results – and those presented in past studies – emphasise the significant impediment melting represents in the formation of granulite facies rocks3,4,5,28. The production of HT-UHT mineral assemblages either requires (1) an energy-intensive process in which both crustal anatexis and significant temperature rise can be accommodated, or (2) a preexisting refractory bulk composition which inhibits subsequent melting and increases the likelihood of (U)HT metamorphism.

Geological background

The Warumpi Province is located along the southern margin of the North Australian Craton (NAC), immediately south of the Aileron Province (Fig. 1), and can be separated into three domains: the Yaya, Haasts Bluff, and Kintore30,31. The present work focuses on samples from the Yaya Domain. The Warumpi Province records two major events, the c. 1640 Ma Liebig Orogeny, and the c. 1150 Ma Musgrave Orogeny18,30,31,32,33,34.

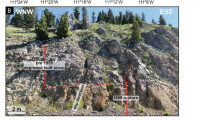

Samples were collected in the Yaya Hills in the western Warumpi Province (Fig. 1). In this area, there are two granulite-grade metapelitic rock systems. The first is a dark-coloured, massive to weakly foliated cordierite–orthopyroxene–sillimanite-rich granulite. Relic quartzite layers, detrital zircon spectra, and abundant sillimanite confirm that it has a sedimentary protolith18,30,35. Compositionally, this metasedimentary unit is characterised by low silica, low Ca and Na, and high Mg–Al relative to an average metapelite. Despite containing biotite, it does not contain leucosomes or K-feldspar-bearing segregations, suggesting the rock did not undergo biotite-breakdown partial melting and peritectic K-feldspar formation (Fig. 2a). The second metapelitic rock system is a strongly layered, quartz-bearing migmatite with abundant leucosomes dominated by K-feldspar (Fig. 2b). The interface between the two domains is marked by an increase in the volume of migmatisation, and a decrease in cordierite and orthopyroxene over an interval of approximately 25 m, leading to orthopyroxene-free, cordierite-poor migmatitic mineral assemblages. These rocks are mostly comprised of garnet, biotite, sillimanite, plagioclase, K-feldspar, quartz, and ilmenite, with minor cordierite. The region has experienced two episodes of HT metamorphism: M1 and M2. M1 metamorphism was associated with the c. 1640 Ma Liebig Orogeny. This was first recognised by Scrimgeour, et al.31 in the Warumpi Province and was initially described as a moderate-pressure HT–UHT event. Subsequent work has established the polymetamorphic nature of Mg–Al-rich metapelites in the Warumpi Province where Lu–Hf garnet geochronology has shown HT–UHT metamorphism is instead associated with the c. 1150 Ma Musgrave Orogeny (M2)18. The Liebig Orogeny has since been redefined as a low-pressure HT event and is recorded in the unmigmatised Mg–Al-rich rocks by coarse-grained orthopyroxene–cordierite–biotite assemblages that formed at 4–5 kbar and 760–850 °C35. There is little mineralogical record of M1 in the migmatitic rocks. M2 metamorphism occurred at 1150 Ma and formed part of the continental-scale Musgrave-Albany Fraser orogenic belt36. In the Mg–Al-rich rocks, M2 metamorphism resulted in the formation of M2 garnet, sillimanite, orthopyroxene, and sapphirine, primarily at the expense of M1 cordierite. Cordierite is still abundant, indicating it forms part of the M2 assemblage, but with a lower modal abundance relative to M118. In contrast, in the migmatitic rocks M2 is characterised by garnet-leucosome-bearing assemblages. M2 metamorphism is associated with pressures between 7 and 10 kbar, however the thermal conditions in Mg–Al-rich rocks (> 850–915 °C) contrast with those of the migmatitic rocks (710–850 °C)18. This presents a prima faci case for partial melting to have slowed the rate of temperature increase in migmatitic rocks relative to the nearby refractory Mg–Al-rich rocks.

Field photographs from the Warumpi Province highlighting M2 mineralogy. (a) Mg–Al-rich metapelite from the 830-4 sample location showing dark massive cordierite-orthopyroxene-garnet bearing rock with layers of quartzite interpreted to represent relic bedding (March et al. 2024a). (b) Migmatitic metapelite from the sample 830 − 20 location.

In this study, we have selected three samples from the migmatised domain, and three samples from the non-migmatised Mg–Al-rich domain to model and compare their respective temperature constraints. These were initially selected with the overarching aim of better understanding the Musgrave Orogeny in the southern part of the North Australian Craton. In total, the samples are separated by ~ 2 km with no apparent structural offsets. However we note the apparent absence of structural discontinuities does not mean they don’t exist, and instead may have been recrystallised and now obscured29. However, in the absence of evidence for notable separation between samples, we assume in this study that they are structurally equivalent and comparable.

Methods

Bulk composition determination

Whole-rock chemical compositional data was collected for all samples at Bureau Veritas, Adelaide to aid in the construction of mineral equilibria forward models. (Supplementary Table S1)18. Chemical compositions were measured using ~ 25 g of crushed material from representative billets cut adjacent to the thin section surface. This ensured mineralogical modes within the thin section were comparable to the measured bulk composition. Lithium metaborate was used to fuse the sample material, with the resultant fused glass then digested in nitric acid. Major and trace element concentrations were measured using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis.

Sample 830-4 is compositionally heterogenous on the thin section scale, so a bulk composition for this sample was calculated using modal proportions from a representative subdomain (Supplementary Fig. S1), in combination with major element mineral compositions acquired using a CAMECA SXFive Electron Probe Microanalyser (EPMA) at Adelaide Microscopy. Minerals were analysed using a 20nA beam current, 15 kV accelerating voltage, and a 5 μm spot size. Representative oxide and cation calculations are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Mineral Equilibria forward modelling

GeoPS v3.2 software was used in the calculation of P–T diagrams for all samples. P–T diagrams were calculated in the model system MnNCKFMASHTO (MnO-Na2O-CaO-K2O-FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O-TiO2-O)37, with ‘HP622’ used as an internally-consistent thermodynamic dataset38, along with relevant metapelitic activity-composition (a-x) models39,40,41,42,43.

Prior to calculating P–T models, pressure–oxidation state (P–MO) and temperature–H2O (T–MH2O) models were constructed as a preliminary investigation into the sensitivity of mineral assemblages to these additional variables (Supplementary Fig. S2, S3). During preliminary modelling for refractory sample 830-4, temperature was fixed at 850 °C and pressure was fixed at 8 kbar, as was the case during modelling for the comparable samples 830-6 and 830-7 in March, et al.18. Similarly, temperature was fixed at 750 °C and pressure at 8 kbar for preliminary modelling of migmatitic sample 830 − 16, as was the case for migmatitic samples 830 − 20 and 830 − 23 in March, et al.18. The results of these models were used to constrain appropriate FeO, Fe2O3, and H2O concentrations for subsequent P–T modelling.

Enthalpy-temperature calculations were also determined for samples 830-4, 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 using GeoPS v3.2 software. Samples 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 show evidence for extensive partial melting. Because melting not only buffers the rate of temperature rise3,4,5, but also results in changes in rock composition due to melt loss, it is necessary to reconstruct plausible bulk compositions prior to melt loss to evaluate the extent of thermal buffering associated with the formation of the present composition. To accommodate for melt loss in samples 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23, melt reintegration modelling following the method of Korhonen, et al.44 was undertaken using the original residual bulk composition as a starting point. The composition of melt directly above the solidus at 8 kbar was multiplied and used to generate a melt-rich bulk composition. To determine the position of the wet solidus, a temperature–composition (T–X) diagram was calculated, with the residual bulk composition at X = 0, and a melt-rich bulk composition at X = 1. Melt reintegrated P–T models were then calculated for samples 830 − 16 and 830 − 20 using the earliest bulk composition from the T–X model where H2O and melt co-crystallised (Supplementary Fig. S4). Line calculations from 6 to 9 kbar and 650–900 °C were determined for each sample and results then exported to generate enthalpy versus temperature diagrams (Supplementary Table S3).

Results

Petrography

The mineralogy of samples 830-4, 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 are summarised in Table 1 and depicted in Fig. 3. In-depth petrographic descriptions are given below for samples 830-4 and 830 − 16 and mineral compositions are provided in Supplementary Table S4. Samples 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 are described briefly here, but in full detail in March, et al.18. A different set of representative photomicrographs for these samples compared to those shown in March, et al.18 have been compiled for the present study.

Photomicrographs from samples 830-4, 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23. (a) 830-4: Fine-grained M2 sillimanite, orthopyroxene, and biotite pseudomorphing M1 cordierite. (b) 830-4: Abundant sillimanite inclusions inside garnet porphyroblasts partially replaced by sapphirine. (c) 830-6: M2 orthopyroxene coronas around M1 orthopyroxene, and fine-grained M2 orthopyroxene, sillimanite, ilmenite, magnetite, and biotite pseudomorphing M1 cordierite. (d) 830-6: M2 garnet enclosing M1 orthopyroxene. (e) 830-7: Cordierite–orthopyroxene symplectite around garnet. (f) 830-7: Intergrown ilmenite, sapphirine, biotite, and quartz inside cordierite. (g) 830 − 16: Garnet porphyroblasts inside a K-feldspar–plagioclase–quartz leucocratic lens. Biotite occurs in association with garnet. (h) 830 − 20: Quartz-plagioclase leucosome and garnet porphyroblasts wrapped by sillimanite–biotite–quartz–plagioclase–ilmenite foliation. (i) 830 − 23: Coarse-grained garnet porphyroblast partially replaced by plagioclase, hornblende, biotite, K-feldspar, ilmenite, and magnetite.

Mg–Al-rich metapelite: 830-4

Sample 830-4 consists of two mineral assemblages. The first-generation assemblage (M1) comprises coarse-grained orthopyroxene (Xopx = 0.26–0.29), cordierite, biotite (Xbi = 0.09–0.10), quartz, and ilmenite. This assemblage is partially replaced by second-generation (M2) garnet, cordierite, biotite (Xbi = 0.15–0.16), sillimanite, orthopyroxene (Xopx = 0.31–0.32), quartz, and sapphirine. M1 orthopyroxene is elongated (up to 5 by 1 mm) and defines a rough layering in the rock. It contains inclusions of biotite, quartz, plagioclase, and ilmenite. Fine- to coarse-grained M1 cordierite (up to 2 mm) is abundant. M2 minerals form the majority of sample 830-4 and are the focus of the present study. The M2 assemblage can be differentiated from M1 by the occurrence of fine to coarse-grained garnet (up to 1 mm), clusters of biotite laths (~ 250 μm), prismatic sillimanite (~ 250 μm), and otherwise fine-grained, intergrown minerals. Fine-grained M2 sillimanite, orthopyroxene, and biotite primarily crystallised via the mode adjustment and resultant pseudomorphing of M1 cordierite (Fig. 3a). Garnet porphyroblasts contain abundant inclusions of fine-grained sillimanite and are partially replaced by fine-grained sapphirine (Fig. 3b). Medium-grained sillimanite (~ 250 μm) is also partially to completely replaced by sapphirine or by fine-grained orthopyroxene.

Mg–Al-rich metapelite: 830-6

The full petrographic description for sample 830-6 can be found in March, et al.18. In brief, sample 830-6 is a polymetamorphic rock. The M1 assemblage is composed of orthopyroxene, cordierite, quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar, and biotite. M2 mineralogy formed primarily via the modal decrease of M1 cordierite. Fine-grained M2 orthopyroxene, sillimanite, ilmenite, magnetite, and biotite occur abundantly throughout M1 cordierite (Fig. 3c). M2 orthopyroxene coronas occur between cordierite and quartz, as well as around coarse-grained M1 orthopyroxene (Fig. 3c). M2 garnet often encloses M1 orthopyroxene and contains inclusions of sillimanite, biotite, cordierite, and quartz (Fig. 3d). Garnet is in contact with all minerals in the rock, including cordierite, suggesting cordierite is also a constituent of the M2 mineral assemblage.

Mg–Al-rich metapelite: 830-7

As described in March, et al.18, sample 830-7 contains two distinct mineral assemblages. The M1 assemblage comprises orthopyroxene, cordierite, biotite, quartz, ilmenite, and magnetite. The M1 assemblage is extensively overprinted by M2 garnet, sillimanite, orthopyroxene, cordierite, biotite, sapphirine, ilmenite, and magnetite. Garnet forms coarse-grained coronas around M1 orthopyroxene. Garnet contains inclusions of cordierite, biotite, plagioclase, magnetite, ilmenite, and sillimanite. Garnet is separated from M1 biotite by symplectitic cordierite, magnetite, and minor K-feldspar. M2 cordierite and orthopyroxene form symplectites around garnet (Fig. 3e). M2 orthopyroxene forms coronas around quartz and biotite. Ilmenite, sapphirine, biotite, and quartz all occur inside M2 cordierite (Fig. 3f). Sapphirine is rarely in contact with garnet. For more detailed petrography, see March, et al.18.

Migmatite: 830 − 16

Sample 830 − 16 only records M2 metamorphism and contains garnet, sillimanite, biotite, K-feldspar, plagioclase, quartz, magnetite, and ilmenite (Fig. 3g). K-feldspar, plagioclase, and quartz commonly form leucocratic patches wrapped by a foliation defined by sillimanite, biotite, K-feldspar, plagioclase, quartz, and minor ilmenite. Garnet is commonly porphyroblastic and coarse-grained (~ 1.5 mm) but may be elongate and aligned with the foliation. Garnet porphyroblasts are moderately fractured and contain inclusions of quartz and biotite. Garnet in the leucocratic segregations is commonly in contact with biotite (Fig. 3g), but garnet zoning profiles do not show evidence for significant resorption (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Migmatite: 830 − 20

Sample 830 − 20 is foliated and only records M2 metamorphism. Garnet is fine- to coarse-grained, where coarse-grained garnet contains abundant inclusions of sillimanite and rare kyanite. Along with aluminosilicates, garnet contains inclusions of quartz, staurolite, rutile, biotite, and magnetite. Garnet porphyroblasts and plagioclase–quartz-bearing leucosomes are wrapped by a sillimanite–biotite–quartz–plagioclase–ilmenite foliation (Fig. 3h). Coarse-grained sillimanite is rimmed by fine-grained intergrowths of biotite and sillimanite. Matrix biotite mostly grows around the margins of sillimanite, suggesting it postdates sillimanite within the foliation. Biotite and sillimanite may be separated from garnet by cordierite and lesser K-feldspar. In some places, cordierite separates sillimanite from biotite. For more detailed petrography, see March, et al.18.

Migmatite: 830 − 23

Sample 830 − 23 is described in detail in March, et al.18. The metamafic sample only records M2 metamorphism and contains garnet-bearing leucocratic segregations comprising plagioclase with lesser hornblende and biotite. Garnet porphyroblasts (up to 3 cm) contain inclusions of plagioclase, magnetite, and titanite. Garnet has been partially replaced by symplectitic plagioclase–hornblende–biotite–K-feldspar–ilmenite–magnetite (Fig. 3i). The matrix of the rock is dominated by plagioclase as well as minor quartz, K-feldspar, ilmenite, magnetite, and titanite.

Mineral Equilibria forward modelling

Warumpi province samples

Samples 830-4 and 830 − 16 are modelled in the present study, and P–T conditions for samples 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 have been previously constrained in March, et al.18. In that study, metapelitic samples 830-6 and 830-7 gave peak M2 temperatures of 870–915 °C. Previous P–T modelling of a migmatitic metapelite (sample 830 − 20) and metamafic (830 − 23) revealed peak temperatures between 700 and 830 °C18. All samples have overlapping peak pressure constraints between 7 and 10 kbar.

Mineral equilibria forward modelling of samples 830-4 and 830 − 16 are detailed below (Fig. 4a, b). A melt reintegrated P–T diagram for sample 830 − 16 is presented in Supplementary Figure S4a. Table 2 is a compilation of peak M2 P–T constraints for samples 830-4, 830-7, 830 − 16, and 830 − 20 using results from this study and March, et al.18.

P–T pseudosection for samples (a) Mg–Al-rich metapelite − 830-4, and (b) Migmatitic rock − 830 − 16. The black, bold outline represents the inferred peak field, and the orange arrow represents the interpreted P–T path. Peak fields are magnified in the inset for each diagram. The kyanite-sillimanite phase transformation is indicated with a wide dashed white line, sapphirine-in by a narrow dashed white line, and the solidus by a dashed black line. Sapphirine-in is indicated in 830-4 by a narrow dashed white line. Variance increases with shading in each diagram. Bulk composition used for the calculation of phase diagrams is given at the top of each model in mol%. Abbreviations: bi = biotite, cd = cordierite, cor = corundum, gt = garnet, hb = hornblende, ilm = ilmenite, kfs = K-feldspar, ky = kyanite, melt = melt, mt = magnetite, opx = orthopyroxene, pl = plagioclase, q = quartz, ru = rutile, sa = sapphirine, sill = sillimanite, sp = spinel. Preliminary diagrams are provided in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3.

Mg–Al-rich metapelite: 830-4

Sample 830-4 records two phases of metamorphism, of which M2 is relevant to the present study. A representative domain and calculated mineral chemistry were used to determine the M2 bulk composition (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2, S5). Relative to the overall bulk rock composition, this calculated M2 effective bulk composition is more aluminous and less siliceous. The earliest record of M2 metamorphism is preserved by sillimanite inclusions inside garnet, suggestive of early coeval growth. Biotite, cordierite, garnet, quartz, and sillimanite are stable above the solidus between 8.4 and 10.2 kbar and 760–890 °C (Fig. 4a), where melt mode remains low. Garnet and sillimanite modes decrease down-pressure, related to the respective modal increase of orthopyroxene and sapphirine at their expense. Accounting for the appearance of sapphirine, orthopyroxene, and plagioclase, and lack of evidence for extensive melting, peak thermal conditions for sample 830-4 must exceed 860 °C. This coincides with a biotite–cordierite–garnet–orthopyroxene–plagioclase–sapphirine–liquid field at 6.2–7.4 kbar and 860–890 °C. Melt in this field is < 3 vol%.

Migmatite: 830 − 16

The mineral assemblage in sample 830 − 16 consists of garnet, sillimanite, biotite, K-feldspar, plagioclase, quartz, magnetite, and ilmenite. K-feldspar, quartz, and plagioclase occur in leucocratic lenses. For the modelled bulk composition, biotite, garnet, ilmenite, K-feldspar, magnetite, plagioclase, sillimanite, and melt are stable at 5.5–8.6 kbar and 770–840 °C (Fig. 4b). Based on the measured garnet mode (8 vol%) and taking into account minor garnet resorption (Supplementary Fig. S5), peak temperatures for sample 830 − 16 are likely between 810 and 840 °C (Fig. 4b). A melt-reintegrated P–T diagram for sample 830 − 16 is provided in Supplementary Figure S4a.

Discussion

Refractory samples 830-4, 830-6, and 830-7 record peak temperatures between 865 °C and > 920 °C, while adjacent migmatitic samples 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 record peak temperatures of 700–855 °C (Figs. 4a and b and 5). Peak temperature constraints for migmatitic samples overlap between 800 and 840 °C, while differing peak temperature constraints between refractory samples may be attributed to the location of their respective solidus. Taking the median of overlapping temperature constraints for migmatitic samples (~ 820 °C) and the median of peak temperature constraints for refractory samples (895 °C), an approximate overall disparity of approximately 75 °C is evident. However, using the overlapping peak temperature constraints of refractory samples 830-6 and 830-7 (~ 910 °C) and excluding sample 830-4, this temperature disparity may be as high as 90 °C. Although we cannot definitively prove the migmatitic samples and the non-migmatitic Mg–Al-rich samples are not separated by structural discontinuity, the absence of evidence for such a feature suggests the temperature difference is not the result of structural juxtaposition. Instead, we suggest this temperature disparity may be attributed to thermal buffering, where rocks have different thermodynamic responses to heat input. The formation of adjacent refractory protoliths and those that are prone to melting during high temperature metamorphism may be facilitated in many unremarkable geological settings, including cover sequences on previously metamorphosed basement rocks or the formation of zones of retrogression within generally more anhydrous rock systems e.g45,46,47. The only criterion is a process that leads to the proximal positioning of melt prone and refractory rocks. Notably, refractory samples in this study record both M1 and M2 metamorphism during the Liebig and Musgrave Orogenies. The presence of Liebig Orogeny-aged monazite in migmatitic samples indicates they also experienced M1 metamorphism34. However, Lu–Hf garnet age data suggests partial melting and granulite facies metamorphism occurred during the Musgrave Orogeny18,35.

Modelled P–T paths and peak fields for migmatitic and refractory samples. The location of the solidus for each refractory samples is indicated by a dashed line, coloured to match that of its respective peak field. Sapphirine-bearing P–T space for samples 830-4 and 830-7 are shaded red and orange, respectively.

Melting and subsequent melt loss is arguably the most common – or at least, most recognised – method of making a refractory bulk composition48,49,50. A compositionally fertile rock experiencing metamorphism and partial melting for the first time is likely to be thermally buffered, but the same rock experiencing a second phase of metamorphism may inherit a dehydrated composition that is resistant to subsequent melt-producing reactions and therefore predisposed to reaching high temperatures compared to associated rocks that are able to melt25,48,49. With this in mind, HT polymetamorphic – as is the case in the present study – or long-lived single metamorphic cycle systems around the world have the potential to contain refractory rocks mixed with more fertile compositions that arise from localised retrograde rehydration45. In this context, the granulite facies M1 event at c. 1.64 Ga may have played an important role in preconditioning the refractory rocks to reach high temperatures during the M2 event. Melting of the now Mg–Al-rich rocks, mobilisation of that melt to form neighbouring migmatites, subsequent retrogression of those melt-bearing rocks and resultant decreased modelled temperatures would usually be a simple answer to the differing temperatures recorded between proximal rocks in the Warumpi Province51. However, despite reaching granulite facies during M1 and M2, the Mg–Al-rich refractory rocks in this study do not show evidence for significant melting. They contain no leucosomes, felsic segregations, or even significant amounts of feldspar. Additionally, their bulk compositions remain hydrous, which makes large-scale melt loss an unlikely scenario. Alternative mechanisms to melt loss that could create a refractory, hydrous, Mg–Al-rich protolith include: (1) low-temperature hydrothermal alteration prior to metamorphism e.g52,53,54,55. , (2) Mg-rich clays e.g56,57,58. , or (3) metasomatism related processes e.g57,59,60. As an example, hydrothermal alteration can profoundly alter the geochemistry of a rock which can then propagate into the ability of that rock to respond to metamorphism. This may occur in the vicinity of ore deposits, but is not restricted to them e.g61,62. In some cases, hydrothermal alteration can effectively facilitate the loss of Si, K, Ca, and Na, and the pervasive formation of Mg–Al-rich chlorite63,64,65. The resultant bulk composition is enriched in Mg and Al, but – unlike rocks that have undergone melt loss – remains significantly hydrous. For example, alteration of sandstones in the vicinity of the Jabiluka mineral deposit in the Northern Territory, Australia has created a pervasive, 200 m wide domain dominated by chlorite, along with white mica, tourmaline, and apatite. Excluding water, these highly metasomatised rocks have bulk compositions similar to Mg–Al rich samples 830-4, 830-6, and 830-7 used in this study (Supplementary Table S3)64. Mineral equilibria forward modelling of these metasomatised rocks reveal similar HT–UHT assemblages to those developed in the Mg–Al-rich rocks from the Yaya Hills. Most notably, the location of the solidus at 8 kbar in both samples sits at above 850 °C (Supplementary Fig. S6, S7). This demonstrates how hydrothermal alteration can drastically modify rocks and generate compositions that are resistant to melting despite containing significant amounts of fluid, meaning melting and melt loss are not the only way to make rock compositions that are difficult to melt.

It is well-recognised that fertile and refractory rocks may respond differently to thermal input if they can expend energy via endothermic processes, such as dehydration or melting1,2,3,4,5,28. Although temperature rise is the most recognised translation of heat input into a system, dehydration reactions and melting are also significant – notably, a system cannot experience direct temperature rise until after these processes have run to completion e.g4,5. As a result, fertile rocks with compositions that are prone to melting will translate less thermal energy into temperature rise than those that are refractory, manifesting in the formation of thermally-contrasting mineral assemblages. This, in turn, can lead to a potential measured temperature offset between rocks that have experienced the same metamorphic event (Figs. 4a and b and 5).

A consequence of this is that a ‘typical’ metapelite in a (U)HT metamorphic terrane may not be the best choice to constrain peak thermal conditions. Metapelitic lithologies are often used for mineral equilibria forward modelling due to their relative sensitivity to pressure and temperature changes e.g40,42,66,67. However, as demonstrated by Schorn, et al.4, the average composition of a metapelite is melt-fertile, rather than refractory68. Melt-fertile rocks have a steep solidus, with melting commencing at ~ 680–700 °C from 2 to 10 kbar. As a result, a typical metapelite in a high-grade metamorphic terrane may not be a reliable measure of peak temperature, where a portion of the heat input may instead be endothermically consumed by melting.

In the Warumpi Province, refractory metapelitic samples 830-4, 830-6, and 830-7 were metamorphosed during the Musgrave Orogeny, are spatially proximal to each other, and record the same down-pressure evolution as migmatitic metapelitic samples 830 − 16 and 830 − 20, and migmatitic metamafic sample 830 − 23 (Figs. 4a and b and 5)18. Unlike the migmatitic rocks where melting at 8 kbar commenced from 650 to 800 °C, the location of the solidus at 8 kbar in refractory rocks occurs at ~ 850–910 °C. Peak temperature constraints in refractory rocks are therefore higher than those recorded in migmatitic rocks – 865 °C to > 925 °C versus 700–855 °C (Figs. 4b and 5)18. The extent of this temperature disparity is additionally governed by the location of the solidus in refractory samples, where sample 830-4 is modelled to have commenced melting and apparently stalled at ~ 865 °C, while samples 830-6 and 830-7 appear to have experienced uninhibited temperature rise until crossing the solidus at ~ 900 °C (Fig. 5). Enthalpy calculations using melt-reintegrated bulk compositions document the potential role of thermal buffering in this temperature disparity, where the slope of modelled enthalpy-temperature curve from 6 to 9 kbar decreases at ~ 680 °C in sample 830 − 20, at 715 °C in sample 830 − 16, and at 770 °C and 815 °C in sample 830 − 23, marking the onset of melting-related reactions and an increase in the enthalpy demand for the system (Fig. 6). Evident in the diagram is the significantly higher energetic requirements for migmatitic samples to obtain equivalent temperatures to Mg–Al-rich samples. Refractory samples 830-4, 830-6, and 830-7 experienced peak modelled temperatures of > 850 °C, which would consume ~ 21 kJmol-1 (x = 850 °C, y = 21 kJmol-1; Fig. 6). In comparison, in order for migmatitic samples 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23 to record the same thermal conditions, an additional 5–8 kJmol-1 would be required (x = 850 °C, y = 26–28 kJmol-1; Fig. 6). We suggest the magnitude of enthalpy ‘jumps’ between individual samples is reflective of both the type of melting reaction (and how energy intensive the phase arrangement is), and the volume of melt produced via that reaction.

Top: Modelled peak temperatures for samples 830-4, 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23. Bottom: Enthalpy (kJmol-1) versus temperature (°C) at 6–9 kbar for samples 830-4, 830-6, 830-7, 830 − 16, 830 − 20, and 830 − 23. The solidus intersection location for each sample along the 6–9 kbar line is shown with a dashed line, coloured to match that of its respective enthalpy versus temperature line. The solidus location for sample 830 − 23 is below the modelled temperature range and the modelled peak conditions for samples 830-6 and 830-7 extend to higher temperature.

The ~ 75 °C temperature disparity recorded between the migmatitic and refractory rocks in the Yaya Hills is substantial. However, it is worth considering the temporal impact of long-lived orogenic events on the degree of thermal buffering recorded in metamorphic rocks. The Musgrave Orogeny spans 1220–1150 Ma69,70,71,72,73,74,75. While the thermal duration of the Musgrave Orogeny is comparatively long, there are presently few constraints on the duration of heating between the wet solidus temperature in melt-fertile rocks and the metamorphic peak. As a result, the period of time the adjacent rocks of contrasting melting behaviour may have experienced different heating rates is not constrained. However, the apparent magnitude of the difference in temperature between the migmatitic and non-migmatitic rocks in the Yaya Hills implies slow overall prograde heating. Although melting has been minimal in Mg–Al-rich rocks in this study – as indicated by the lack of leucosomes and peritectic K-feldspar – it is worth noting that these rocks would also experience a degree of thermal buffering after crossing the solidus. Long-lived regional metamorphism could be a feasible explanation for the modelled 75–90 °C of thermal buffering recorded between refractory and fertile rocks in the Yaya Hills of the Warumpi Province.

Conclusion

Compositional differences and contrasting melting behaviours can create significant thermal disparities between otherwise geologically analogous rocks. In this study, mineral equilibria forward modelling of neighbouring refractory and fertile lithologies from the Warumpi Province, central Australia highlight the thermal stall experienced by migmatitic rocks at the onset of melting. The result of this are modelled peak temperatures of 700–855 °C in rocks that melted versus peak temperatures of 865 °C to > 920 °C in rocks that did not. In order for migmatitic rocks to record the same temperatures as refractory rocks, an additional 5–8 kJ mol-1 would be required, equating to 22–37% more enthalpy input. We suggest the development of refractory rocks in the Warumpi Province may be the result of early hydrothermal alteration and metamorphism, creating hydrated, Mg–Al-rich bulk compositions that are resistant to melting.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Bea, F. The sources of energy for crustal melting and the geochemistry of heat-producing elements. Lithos 153, 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.201201.017 (2012).

Thompson, A. B. & Connolly, J. A. D. Melting of the continental crust: some thermal and petrological constraints on anatexis in continental collision zones and other tectonic settings. J. Phys. Res. 100, 15565–15579. https://doi.org/10.1029/95JB00191 (1995).

Schorn, S. & Diener, J. F. A. seemingly disparate temperatures recorded in coexisting granulite facies lithologies. J. Metamorph. Geol. 37, 1049–1078. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12500 (2019).

Schorn, S., Diener, J. F. A., Powell, R. & Stüwe, K. Thermal buffering in the orogenic crust. Geology 46, 643–646. https://doi.org/10.1130/G40246.1 (2018).

Stüwe, K. Thermal buffering effects at the solidus. Implications for the equilibration of partially melted metamorphic rocks. Tectonophysics 248, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(94)00282-E (1995).

Spear, F. Metamorphic Phase Equilibria and pressure-temperature-time Paths799 (Mineralogical Society of America, 1993).

Schorn, S., Moulas, E. & Stüwe, K. Exothermic reactions and 39Ar–40Ar thermochronology: hydration leads to younger apparent ages. Geology 52, 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1130/G51776.1 (2024).

Wing, B. A., Ferry, J. M. & Harrison, T. M. Prograde destruction and formation of monazite and allanite during contact and regional metamorphism of pelites: petrology and geochronology. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 145, 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-003-0446-1 (2003).

Corrie, S. L. & Kohn, M. J. Trace-element distributions in silicates during prograde metamorphic reactions: implications for monazite formation. J. Metamorph. Geol. 26, 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2008.00769.x (2008).

Hrushikesh, H., Prabhakar, N. & Bhattacharya, A. Mesoproterozoic P–T–t–d history in the Vinjamuru domain, Nellore schist belt (SE India), and implications for SE India–East Antarctica correlation. Precambrian Res. 327, 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2019.04.002 (2019).

Kelsey, D. E. et al. (eds) Industry Regulation and Safety Department of Mines) (Geological Survey of Western Australia, (2022).

Kelsey, D. E., Korhonen, F. J., Romano, S. S. & Spaggiari, C. V. (eds) (ed Industry Regulation and Safety Department of Mines) (Geological Survey of Western Australia, (2022).

Kim, H. S. & Yi, K. Multiple metamorphic episodes recorded in the paleozoic pyeongan supergroup on the northeastern margin of the Yeongnam massif, South Korea: implications for the Songrim (Indosinian) orogeny. J. Asian Earth Sci. 113, 883–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2015.09.012 (2015).

Tarantola, A. et al. Metamorphic and metasomatic Kyanite-Bearing Mineral assemblages of Thassos Island (Rhodope, Greece). Minerals 9, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9040252 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Zircon-monazite geochronology and P-T evolution of the Sargur Greenstone Belt: implications for the end-archean tectonics of the Dharwar Craton in southern India. Precambrian Res. 364, 106384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2021.106384 (2021).

Zorigtkhuu, O., Tsunogae, T. & Dash, B. Metamorphic P–T evolution of garnet–kyanite–staurolite schist and garnet amphibolite from Bodonch area, western Mongolian Altai: Geothermobarometry and mineral equilibrium modeling. J. Asian Earth Sci. 42, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2011.04.026 (2011).

Clark, C. et al. Granulites Granulites 1–78 (2013).

March, S., Hand, M., Morrissey, L. J. & Kelsey, D. E. The inhibited response of accessory minerals during HT reworking. J. Metamorph. Geol. 42, 257–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12754 (2024a).

Osanai, Y. et al. Geology of ultrahigh-temperature metamorphic rocks from Tonagh Island in the Napier Complex, East Antarctica. Polar Geoscience. 14, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.15094/00003040 (1999).

Ouzegane, K., Kienast, J., Bendaoud, A. & Drareni, A. A review of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic evolution of the In Ouzzal granulitic terrane (western Hoggar, Algeria). J. Afr. Earth Sc. 37, 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2003.05.002 (2003).

Sandiford, M. The metamorphic evolution of granulites at Fyfe Hills; implications for archaean crustal thickness in Enderby Land, Antarctica. J. Metamorph. Geol. 3, 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.1985.tb00312.x (1985).

Sandiford, M. & Wilson, C. J. L. The structural evolution of the Fyfe Hills-Khmara Bay region, Enderby Land, East Antarctica. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 31, 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/08120098408729301 (1984).

Sandiford, M. & Wilson, C. J. L. The origin of archaean gneisses in the Fyfe Hills Region, Enderby Land; field occurrence, petrography and geochemistry. Precambrian Res. 31, 37–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9268(86)90064-1 (1986).

Depine, G. V., Andronicos, C. L. & Phipps-Morgan, J. Near-isothermal conditions in the middle and lower crust induced by melt migration. Nat. Lett. 452, 80–83 (2008).

Brown, M. & Korhonen, F. J. Some Remarks on Melting and Extreme Metamorphism of Crustal Rocks (Springer, 2009).

Bridgwater, D., McGregor, V. R. & Myers, J. S. A horizontal tectonic regime in the Archaean of Greenland and its implications for early crustal thickening. Precambrian Res. 1, 179–197 (1974).

O’Hara, M. J. & Yarwood, G. High pressure-temperature point on an archaean geotherm, implied magma genesis by crustal anatexis, and consequences for garnet-pyroxene thermometry and barometry. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 288, 441–456 (1978).

Diener, J. F. A. & Macey, P. H. Orogen-scale uniformity of recorded granulite facies conditions due to thermal buffering and melt retention. J. Metamorph. Geol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12778 (2024).

dos Bentos, T. et al. Exhumation of an anatectic complex by channel flow and extrusion tectonics: structural and metamorphic evidence from the Porto–Viseu Metamorphic Belt, Central-Iberian Zone. Int. J. Earth Sci. 110, 2179–2201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-021-02067-z (2021).

Scrimgeour, I. R., Kinny, P. D., Close, D. F. & Edgoose, C. J. High-T granulites and polymetamorphism in the southern Arunta Region central Australia: evidence for a 1. 64 Ga accretional event. Precambrian Res. 142, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2005.08.005 (2005b).

Scrimgeour, I. R., Close, D. F. & Edgoose, C. Mount Liebig Northern Territory. 1 250 000 Geological Map Series Explanatory Notes, SF 52 – 16. Northern Territory Geological Survey, Darwin and Alice Springs (2005).

Hoatson, D. M., Sun, S. & Claoué-Long, J. Proterozoic mafic–ultramafic intrusions in the Arunta Region, central Australia. Part 1: geological setting and mineral potential. Precambrian Res. 142, 93–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2005.09.004 (2005).

Morrissey, L. J., Payne, J. L., Kelsey, D. E. & Hand, M. Grenvillian-aged reworking in the North Australian Craton, central Australia: constraints from geochronology and modelled phase equilibria. Precambrian Res. 191, 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2011.09.010 (2011).

Wong, B. L., Morrissey, L. J., Hand, M., Fields, C. E. & Kelsey, D. E. Grenvillian-aged reworking of late paleoproterozoic crust of the southern North Australian Craton, central Australia: implications for the assembly of Mesoproterozoic Australia. Precambrian Res. 270, 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2015.09.001 (2015).

March, S., Hand, M., Morrissey, L. J. & Kelsey, D. E. Extension during the Liebig Orogeny: revised tectonic setting of Paleoproterozoic central Australia. Gondwana Res. 134, 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2024.07.013 (2024).

Tucker, N. M., Hand, M., Kelsey, D. E. & Dutch, R. A. A duality of timescales: short-lived ultrahigh temperature metamorphism preserving a long-lived monazite growth history in the Grenvillian Musgrave–Albany–Fraser Orogen. Precambrian Res. 264, 204–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2015.04.015 (2015).

Xiang, H., Connolly, J. A. D. & GeoPS An interactive visual computing tool for thermodynamic modelling of phase equilibria. J. Metamorph. Geol. 40, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12626 (2021).

Holland, T. J. & Powell, R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. J. Metamorph. Geol. 29, 333–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2010.00923.x (2011).

Holland, T. J. & Powell, R. Activity–composition relations for phases in petrological calculations: an asymmetric multicomponent formulation. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 145, 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-003-0464-z (2003).

Wheller, C. J. & Powell, R. A new thermodynamic model for sapphirine: calculated phase equilibria in K2O – FeO – MgO – Al2O3 – SiO2 – H2O – TiO2 – Fe2O3. J. Metamorph. Geol. 32, 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12067 (2014).

White, R. W., Powell, R. & Clarke, G. L. The interpretation of reaction textures in Fe-rich metapelitic granulites of the Musgrave Block, central Australia: constraints from mineral equilibria calculations in the system K2O–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O–TiO2–Fe2O3. J. Metamorph. Geol. 20, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0263-4929.2001.00349.x (2002).

White, R. W., Powell, R., Holland, T. J., Johnson, T. E. & Green, E. C. R. New mineral activity-composition relations for thermodynamic calculations in metapelitic systems. J. Metamorph. Geol. 32, 261–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12071 (2014).

White, R. W., Powell, R., Holland, T. J. & Worley, B. A. The effect of TiO2 and Fe2O3 on metapelitic assemblages at greenschist and amphibolite facies conditions: mineral equilibria calculations in the system K2O–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O–TiO2–Fe2O3. J. Metamorph. Geol. 18, 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1314.2000.00269.x (2000).

Korhonen, F. J., Brown, M., Clark, C. & Bhattacharya, S. Osumilite–melt interactions in ultrahigh temperature granulites: phase equilibria modelling and implications for the P–T–t evolution of the Eastern Ghats Province, India. J. Metamorph. Geol. 31, 881–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12049 (2013).

Morrissey, L. J., Hand, M., Kelsey, D. E. & Wade, B. Cambrian High-temperature reworking of the Rayner–Eastern Ghats Terrane: constraints from the Northern Prince Charles Mountains Region, East Antarctica. J. Petrol. 57, 53–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egv082 (2016).

Madlakana, N., Stevens, G. & Bracciali, L. Paleoproterozoic amphibolite facies retrogression and exhumation of Archean metapelitic granulites in the southern marginal zone of the Limpopo Belt, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 337, 105532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2019.105532 (2020).

Huang, G., Guo, J. & Palin, R. Phase equilibria modeling of anatexis during ultra-high temperature metamorphism of the crust. Lithos 398–399 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106326 (2021).

Vielzeuf, D., Clemens, J. D., Pin, C. & Moinet, E. In Granulites and Crustal EvolutionVol. 311 (Springer, 1990).

Clark, C., Fitzsimons, I. C. W., Healy, D. & Harley, S. L. How does the continental crust get really hot? Elements 7, 235–240. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.7.4.235 (2011).

Vielzeuf, D. & Holloway, J. R. Experimental determination of the fluid-absent melting relations in the pelitic system. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 98, 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00375178 (1988).

Kelsey, D. E. & Hand, M. On ultrahigh temperature crustal metamorphism: phase equilibria, trace element thermometry, bulk composition, heat sources, timescales and tectonic settings. Geosci. Front. 6, 311–356 (2015).

Vallance, T. G. Mafic rock alteration and isochemical development of some cordierite-anthophyllite rocks. J. Petrol. 8, 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/8.1.84 (1967).

Chinner, G. A. & Fox, J. S. The origin of cordierite—anthophllite rocks in the Land’s end aureole. Geol. Mag. 111, 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800039959 (1974).

Grew, E. S. Sapphirine, kornerupine, and sillimanite + orthopyroxene in the charnockitic region of south India. J. Geol. Soc. India. 23, 469–505 (1982).

Baba, S., Shinjo, R. & Windley, B. F. Origin of sapphirine-bearing garnet-orthopyroxene granulites: possible hydrothermally altered ocean floor. Polar Sci. 2, 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2008.04.003 (2008).

Harley, S. L. Sapphirine granulites from the Vestfold Hills, East Antarctica: geochemical and metamorphic evolution. Antarct. Sci. 5, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102093000525 (1993).

Sheraton, J. W., England, R. N. & Ellis, D. J. Metasomatic zoning in sapphirine-bearing granulites from Antarctica. BMR J. Australian Geol. Geophys. 5, 279–288 (1982).

Reinhardt, J. Cordierite-anthophyllite rocks from north-west Queensland, Australia: metamorphosed magnesian pelites. J. Metamorph. Geol. 5, 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.1987.tb00396.x (1987).

Dunkley, D. J., Clarke, G. L. & Harley, S. L. Diffusion metasomatism in silica-undersaturated sapphirine-bearing granulite from Rumdoodle Peak, Framnes Mountains, east Antarctica. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 134, 264–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004100050483 (1999).

Möller, A., O’Brien, P. J., Kennedy, A. & Kröner, A. Linking growth episodes of zircon and metamorphic textures to zircon chemistry: an example from the ultrahigh-temperature granulites of Rogaland (SW Norway). Geol. Soc. Lond. Special Publications. 220, 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.220.01.04 (2003).

McFarlane, C. R. M., Mavrogenes, J. A. & Tomkins, A. G. Recognizing hydrothermal alteration through a granulite facies metamorphic overprint at the challenger au deposit, South Australia. Chem. Geol. 243, 64–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2007.05.010 (2007).

Tomkins, A. G. & Mavrogenes, J. A. Mobilization of gold as a Polymetallic Melt during Pelite Anatexis at the Challenger Deposit, South Australia: a metamorphosed Archean Gold Deposit. Econ. Geol. 97, 1249–1271. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.97.6.1249 (2002).

Billault, V., Beaufort, D., Patrier, P. & Petit, S. Crystal chemistry of Fe-sudoites from uranium deposits in the Athabasca Basin (Saskatchewan, Canada). Clays Clay Miner. 50, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1346/000986002761002847 (2002).

Nutt, C. J. Chloritization and associated alteration at the Jabiluka unconformity-type uranium deposit, Northern Territory, Australia. Can. Mineral. 27, 41–58 (1989).

Percival, J. B. & Kodama, H. Sudoite from Cigar Lake, Saskatchewan. Can. Mineral. 27, 633–641 (1989).

White, R. W., Powell, R. & Holland, T. J. Progress relating to calculation of partial melting equilibria for metapelites. J. Metamorph. Geol. 25, 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2007.00711.x (2007).

Lanari, P. & Hermann, J. Iterative thermodynamic modelling—part 2: tracing equilibrium relationships between minerals in metamorphic rocks. J. Metamorph. Geol. 39, 651–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12575 (2020).

Ague, J. J. Evidence for major mass transfer and volume strain during regional metamorphism of pelites. Geology 19, 855–858. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0855:EFMMTA>2.3.CO;2 (1991).

Edgoose, C., Scrimgeour, I. R. & Close, D. F. Geology of the Musgrave Block, Northern Territory48 (Northern Territory Geological Survey, 2004).

Smithies, R. H. et al. Geochemistry, Geochronology, and Petrogenesis of Mesoproterozoic Felsic Rocks in the Western Musgrave Province of Central Australia, and Implication for the Mesoproterozoic Tectonic Evolution of the Region73 (Geological Survey of Western Australia, 2010).

Howard, H. M. et al. The Geology of the West Musgrave Province and the Bentley Supergroup — a Field Guide119 (Geological Survey of Western Australia, 2011).

Smithies, R. H. et al. High-temperature granite magmatism, crust-mantle interaction and the mesoproterozoic intracontinental evolution of the Musgrave Province, Central Australia. J. Petrol. 52, 931–958. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egr010 (2011).

Smithies, R. H. et al. The mesoproterozoic thermal evolution of the Musgrave Province in central Australia—Plume vs. the geological record. Gondwana Res. 27, 1419–1429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2013.12.014 (2015).

Smithies, R. H., Spaggiari, C. V., Kirkland, C. L. & Maier, W. D. Geochemistry and petrogenesis of igneous rocks in the Albany–Fraser Orogen. 69–80 (2014). (Geological Survey of Western Australia.

Howard, H. M. et al. The burning heart — the proterozoic geology and geological evolution of the West Musgrave Region, central Australia. Gondwana Res. 27, 64–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2014.09.001 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and pay their respects to the Luritja people, the Traditional Custodians of the land on which the samples used in this study were collected. EPMA analysis was completed at Adelaide Microscopy with the assistance of Benjamin Wade. Samantha March acknowledges financial support from the Robert Francis Thyer Award, Playford Trust PhD Scholarship, Australian Institute of Geoscientists Student Bursary, and the Geological Society of Australia Endowment Fund. Martin Hand is supported by the Australian Research Council grant, DP220103037. Laura Morrissey is supported by an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellowship, DE210101126. David Kelsey publishes with the permission of the Executive Director, Geological Survey of Western Australia. Two anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive reviews, and Biswajit Ghosh is acknowledged for editorial handling of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. MH: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. LM: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. DK: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

March, S., Hand, M., Morrissey, L. et al. Thermal buffering-controlled temperature variation between Mg–Al-rich rocks and migmatites. Sci Rep 15, 3038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87496-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87496-5