Abstract

The interaction mechanism of dolomite rock mineral as a novel corrosion inhibitor for titanium alloy in phosphoric acid (0.001–0.5 M) has been investigated for the first time using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and potentiodynamic polarization measurements. Unlike prior studies on synthetic inhibitors, this work uniquely highlights the potential of a naturally abundant, eco-friendly mineral for corrosion mitigation. EIS results reveal a distinctive shift in the inhibition mechanism—from adsorption to diffusion-controlled processes—with increasing phosphoric acid concentration, corroborated by in-situ Raman spectroscopy. This is the first report showing that dolomite effectively reduces the corrosion rate of titanium alloy by forming a stable passive film, with optimal performance observed in low acid concentrations (0.001–0.01 M). Furthermore, at higher acid concentrations (0.1–0.5 M), the mechanism transition influences the film performance. Surface characterization using SEM, EDS, FTIR, XRD, XRF, and in-situ Raman spectroscopy confirms the protective film formation and elucidates the interaction chemistry. The study establishes dolomite as a sustainable alternative to synthetic inhibitors, offering new insights into corrosion protection strategies for titanium alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Titanium and its alloys are very reactive in an aerated environment; a thin titanium dioxide compact, stable, and adherent film is fabricated. This is responsible for their excellent corrosion resistance1,2,3. The superior properties and excellent corrosion resistance of titanium alloys make them ideal for marine usages such as submersible vehicles and in risers in offshore oil drilling4. Furthermore, their biocompatibility and acceptable degradation rates enables their use in medical implants and other biomedical applications5. Titanium alloys can be utilized as metallic biomaterials due to its acceptable degradation rate5,6,7,8,9. Despite these advantages, titanium or its alloys undergo corrosion in violent surroundings forming uniform corrosion and localized corrosion: crevice and pitting, hydrogen embrittlement, stress-corrosion cracking, fretting corrosion and erosion1.

Phosphoric acid is a vital industrial acid due to its greater chemical properties and acts as an aggressive medium whereas it poses a significant challenge to the stability of titanium’s passive film10,11,12. The acid has been extensively used to study the active passive behavior of titanium and its alloys, shedding light on their electrochemical properties in reducing acid solution13,14. Corrosion inhibitors can be utilized to prevent metal corrosion and reduce hydrogen evolution in corrosive media15,16,17,18,19.

To combat these issues, various studies of corrosion behavior and the type of passive film have been conducted on titanium and its alloys20,21. Organic inhibitors, including heterocyclic molecules, aminoacids, and biopolymers, have demonostrated efficacy in reducing corrosion rates by forming protective films on the alloy surface14,19. Inorganic compounds like phosphate based and silicate based inhibitors have also been widely studied for their effectiveness in enhancing the stability of the passive film22,23. The electrochemical behavior of titanium was explained in terms of a two-layer passive film structure. Due to its low cationic conductivity and porous outer layer, a barrier film next to the metal prevents the metal from dissolving13. Many studies have looked at titanium’s active dissolving and passive behavior in mineral acids such as sulfuric, hydrochloric, phosphoric, and perchloric acids24. The instability and considerable failure of Ti and its alloys in reducing acid solution have been prompting researchers to investigate the electrochemical behavior of Ti in such a medium14.

Dolomite CaMg(CO3)2, one of the most abundant rocks, appears to be the cheapest and most readily available raw material. It is well known as double carbonates, which are good sorbents of heavy and nonferrous metals22. The most common use for dolomite is in the construction industry. Corrosion protection is one of the many uses for dolomite, particularly in water distribution systems. Water filters, pipe linings, and backfill are all made of dolomite23. Raw dolomite powder was discovered to be a highly effective adsorbent for removing low levels of phosphates from a variety of water and waste water matrices25.

Generally, dolomite and apatites (hydroxylapatite, fluorapatite, francolite, etc.) are the principal phosphate minerals of sedimentary phosphates ores26. Amongst these minerals, apatite, calcite, dolomite, barite, fluorite, scheelite, and any salt-type minerals which are highly soluble in aqueous media may be simply separated by flotation from oxides and silicates27,28. Therefore, the separation of these minerals are significant. The separation of apatite/calcite was studied previously by depressing apatite and preventing collector’s adsorption on its surface28,29,30. Usually, phosphoric acid is used as a depressor of the apatite when the calcite and dolomite are floated using the fatty acid-based reagents as collector31,32,33,34.

The investigation into dolomite’s ability to prevent titanium alloy corrosion in phosphoric acid contributes to the expanding corpus of work on environmentally friendly corrosion prevention techniques. Prior research has examined a range of synthetic and organic inhibitors, emphasizing the importance of material selection for environmental sustainability and efficacy. Bhat et al.35,36,37,38,39 investigated the use of organic coatings and electrochemical methods and demonstrated significant promise in preventing corrosion on Zn-Ni or Zn-Fe alloys. In the creation of protective films in dolomite, Bhat et al. analysis the relationship between coating thickness and corrosion resistance may be helpful which provided information on how protective films functioned in different situations. He also emphasizes the role of material properties and environmental factors in corrosion behavior and made a transition from adsorption to diffusion-controlled inhibition with increasing acid concentration. Whereas, these findings align with the broader discussion on the role of inhibitors in altering surface reactions and extending the lifespan of materials exposed to aggressive environments. Moreover, He provides further context on the challenges and advantages of natural versus synthetic corrosion inhibitors, underlining the importance of developing cost-effective and eco-friendly alternatives, a concept central to your study’s innovation.

To fill this research gap, we will investigate how dolomite interacts with the surfaces of titanium alloys and phosphoric acid to provide corrosion resistance. Herein, it is wanted to study the mechanism of the reaction for dolomite with phosphoric acid and titanium alloy surface to protect it from corrosion. For our knowledge, no corrosion studies have been done using dolomite mineral as an inhibitor for Ti-alloy in phosphoric acid solution. The aim of this work is to evaluate the performance of dolomite material as a natural environmental inhibitor for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid with different concentrations (0.001–0.5 M).

Materials and methods

Dolomite quarries have been obtained from Cairo – Suez road, Egypt. After that, the rock has been crushed, grounded and then grinded to be fine using mortar; and then it is used. Dolomite composition done by XRF is given in Table 1A.

Ti-6Al-4 V alloy was utilized with a cross-sectional area of 0.196 cm2. It is manufactured by Johnson and Matthey (England) with elemental compositions given in Table 1B.

The electrode was successively polished with SiC papers (600–2400 grit); and then washed with triply distilled water; and cleaned in an ultrasonic bath containing acetone; and then left to dry in air. A conventional three-electrode cell containing Ti-6Al-4 V alloy as working electrode (WE), a platinum sheet as a counter electrode (CE) and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode (RE) is used.

The working electrode (Ti alloy) is immersed in 100 mL solution of water and/or different acid concentrations (0.001 M to 0.5 M) with and without dolomite mineral. The amount of mineral as an inhibitor added is 3 g (3%). It has been added in solution with agitation of 245 rpm for 1 h of immersion.

The test solution was prepared from phosphoric acid in different concentrations 0.001-0.5 M (Sigma Aldrich) with or without 3% dolomite inhibitor. All solutions were manufactured by triple distilled water.

Electrochemical measurements were performed utilizing EC-Lab SP 150 Potentiostat electrochemical unit. Potentiodynamic polarization experiments were achieved at a scan rate of 1 mV/s. Before beginning the potentiodynamic measurements, the open-circuit potentials (OCP) were stabilized for 60 min. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed in the frequency range of 100mHz–100 kHz, with a perturbation amplitude of 5 mV. All experiments were repeated two or three times to have reproducible results. A Quanta 250 FEG (Field Emission Gun) scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) unit (FEI business, Netherlands) was employed. Also, GeoRessources - SCMEM Tescan VEGA3 was used. A IR-Affinity-1, serial A21374701135S1 made in Japan from Shimadzu corporation used to measure FTIR. PANanalytical X-Ray Diffraction equipment model X-Pert PRO with secondary Monochromator, Cu-radiation (λ = 1.542Å) at 45 kV., 35 mA. and scanning speed 0.04°/s were used.

A Philips X-ray fluorescence equipment, model Philips PW/2404, with Rh target and six analyzing crystals has been used for determining major and trace elements. Crystals (LIF – 200), (LIF – 220) were used for estimating Ca, Fe, K, Ti, Mn and other trace elements from Nickel to Uranium while crystal (TIAP) was used for determining Mg and Na. Crystal (Ge) was used for estimating P and crystal (PET) for determining Si and Al and PXI for determining Na and Mg. The concentration of the analyzed elements was determined by using software Kernl X-44.

The pH of the solution was measured by a pH meter (Hanna) after calibration with standard solutions of pH 4.01, 7.00 and 10.0.

Raman spectra were collected at wavenumber in the range of 200–4000 cm− 1 by RXN4 spectrometer (Kaiser) at a laser excitation wave-length of 532 nm, with a fiber-optic Raman sampling probe. The sapphire-head probe gives Raman peaks at 377, 417, 447, 576 and 749 cm− 1.

The Raman spectroscopy experiment was done for 3 g of the sample of dolomite in 100 mL of deionized water and/or phosphoric acid solutions at concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 M, and stirred at 200–300 rpm for1 h.

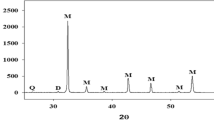

The dolomite sample chemical and mineralogical compositions are determined to check its purity. The XRD (Fig. 1) analysis shows that the sample is relatively pure and doesn’t contain other minerals in significant proportion except for a small amount of quartz and tremolite.

The dolomite raw samples’ primary peaks were indexed using the dolomite MgCa(CO3)2 reference pattern (JCPDS Card No. 075-1761). With regards to the unprocessed dolomite samples, it was verified that rhombohedral dolomite was present with reflections at 2θ ∼ 31.02°, 33.68°, 35.43°, 43.93°, and 52.354° which corresponded to the planes (104), (006), (015), (021), and (205).

Results and discussion

Surfaces morphology and characterization

Figure 2A shows the SEM photos of Ti-alloy surface without any addition as a bare electrode40. Figure 2B shows the alloy after treatment with dolomite rock mineral in phosphoric acid solution for 1 h at 0.01 M showing the mineral adsorbed film. It seems to be better due to the formation of Ca and Mg phosphate film at this concentration with TiO2 film1,2,3,4,5,32. Figure 2C is the EDX analysis confirming the presence of all elements forming this film.

SEM images of (A) Ti alloy surface40 and (B) after adding dolomite sample in 0.01 M phosphoric acid solution after 1 h of immersion with its EDX analysis (C).

Electrochemical impedance measurements

Nyquist plots of Ti-6Al-4 V alloy (A) in pure water and (B) in phosphoric acid of different concentrations at 1 h of immersion without dolomite2.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) technique was performed for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in both pure water and phosphoric acid of different concentrations at 1 h of immersion without dolomite, respectively and the results are presented in Fig. 3A, B.

The alloy in water works with both adsorption (semicircle) and diffusion (line) mechanism, however, on phosphoric acid, it is only adsorption mechanism (semicircle)34,41. The impedance value in acidic medium decreases than in water due to its violence.

The Nyquist plots (Fig. 4) after adding dolomite show higher impedance value than without dolomite with immersion time owing to the dissolution and precipitation of dolomite in water as carbonate and thickening of passive TiO2 film on the alloy surface1,6,42,43,44,45.

Dolomite dissolves with release of Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations that cause precipitates to be developed on the alloy surface, forming a protective coating of either Mg or Ca phosphates depending on phosphoric acid concentration. Hard water with high calcium and magnesium content is less corrosive than soft water forming protective coating45,46. Here is the same case where water containing dolomite has high calcium and magnesium content that are adsorbed on alloy surface leading to an increase in impedance value.

In order to study the protective effect and mechanism of dolomite mineral in phosphoric acid. The impedance diagrams for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid with different concentrations (0.001–0.5 M) containing 3% dolomite as a function of immersion time represented in Fig. 5(a-e). The Nyquist plots show the same trend with considerable decrease in impedance value than that of pure water due to the corrosive and aggressiveness effect of phosphoric acid. They show the highest corrosion resistance of dolomite mineral as an inhibitor for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy at the lower H3PO4 concentration up to 0.01 M indicating the formation of a thicker compact protective film (SEM image in Fig. 2B) by adsorption of dolomite on the alloy surface by forming magnesium and calcium phosphate salts. On further increasing H3PO4 concentration, the mechanism of adsorption on titanium alloy of undissolved dolomite changes to diffusion and charge transfer resistance. This is due to adsorption resistance decreases and diffusion resistance increases slightly. The film starts to deteriorate at 0.1 M concentration of phosphoric acid due to forming magnesium and calcium phosphate porous film10. It is well known that magnesium phosphate is less soluble than calcium phosphate. On increasing acid concentration calcium phosphate mostly dissolve34. Also, the compact film converted to porous film with increasing diffusion phenomena and hydrogen evolution rate reaching the top at 0.5 M phosphoric acid solution. Therefore, the corrosion performance for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy reflects the dissolution of the protective oxide film on the alloy surface as the corrosiveness of the acidic medium is increased. The dissolution reaction for the oxide film on Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid solution might be written as6:

The reaction between dolomite and dilute phosphoric acid at room temperature can be described by the equation:

The extent of the reaction depends on H3PO4 concentration, pH, relative amounts of solid and liquid phases, temperature, and reaction time10,46.

The best-fit model for Nyquist plots, used to obtain the parameters in Tables 2 and 3, is the Randles circuit with two time constant. It is represented in Fig. 6 and used for water or phosphoric acid without and with dolomite mineral using EC software. It comprises of a parallel combination of a capacitors (C1, C2) as a constant phase element (CPE) that is parallel to the surface film’s polarization resistance (R1). Warburg impedance (W) is due to diffusion mechanism and is connected to the solution resistance (Rs). Because of the non-homogeneity of the electrode surface, CPE34,47,48,49 is utilized instead of capacitances in the two circuits (C1 and C2).

Where α is an exponent account for surface heterogeneity, 0 ≤ α ≤ 1, j is the imaginary number (j = (-1)1/2), ω = 2πf is the angular frequency in rad/s, f is the frequency in Hz = s− 1.

The impact of dolomite as an inhibitor is examined in H3PO4 acid solution of different concentrations (0.001-0.5 M) without and with 3% dolomite as represented in Figs. 3 and 5, respectively. The results showed that the presence of 3% dolomite in phosphoric acid concentrations improved the resistance of the titanium electrode. The corrosion parameters are given in Tables 2 and 3.

This ensures the effectiveness of dolomite rock material that works with adsorption mechanism at low aggressive medium and converts to diffusion especially at high concentration of phosphoric acid giving higher Warburg impedance values. However, even it gives the lowest resistance at higher concentration of phosphoric acid but still working as a good inhibitor (Fig. 7). This is because of forming two films of Ca and Mg phosphate compared to the electrode without dolomite mineral at the same concentration.

Here (Fig. 7) are so clear that the best concentration is 0.01 M concentration after 1 h of immersion, it is better than water starting at 25 min of immersion. Generally, all the films are stabilized after 10 to 20 min. Also, the resistance at 0.25 M and 0.5 M nearly reaches to the same resistance starting from 15 min to 1 h of immersion. The same is for the capacitance value which is reversible proportional to the resistance confirming that the thickness of the film increases with time at all concentrations.

Raman kinetic analysis of dolomite

Impedance results can be confirmed by Insitu-Raman spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 8, It is seen, Raman spectra of phosphoric acid with different concentrations without dolomite.

The Raman spectra of the phosphoric acid solutions with various concentrations (without mineral existence) are displayed in Fig. 8. The peaks containing this sign (*) are the probe peaks that is used for measurements. There are four peaks appear at 501, 890 cm− 1, 1075 cm− 1 and 1175 cm− 1 which increase in intensity with the acid concentration: the main one is at 890 cm− 1 while the others are of lower intensity. These peaks appear only at phosphoric acid concentrations higher than 0.01 M and are related to symmetric vibrations of PO4 group34.

Raman spectra after adding dolomite mineral to phosphoric acid are displayed in Figs. 9, 10 and 11.

Figure 9 displays the Raman spectra of dolomite after contact with phosphoric acid for 1 h of immersion. The main peak at 876 cm− 1 that is related to H2PO4 vibration, it starts to appear at 0.1 M phosphoric acid concentration as a new peak changed its place from 880 to 870 cm− 1 (10 cm− 1 displacement change) as seen in the inset. It upsurges in intensity with increasing phosphoric acid concentration upper than 0.1 M (Figs. 10 and 11). Also, the same happened at 501 to 518 cm− 1 (17 cm− 1 displacement change) like that at 890 cm− 1 with immersion time. The peak at 1075 cm− 1 is related also to phosphoric acid concentration. In addition, it gives the highest intensity at 0.5 M phosphoric acid due to forming two films of Ca and Mg phosphate. This is due to the strong reaction between phosphoric acid and dolomite mineral at high concentrations. The peak at 1175 cm− 1 is broadened with time at all concentrations and disappeared at 0.1 M concentrations or lower. The peak at 1097 cm− 1 is due to carbonate vibrations. Peaks with low intensity are detected at 277 cm− 1 owing to CaO or MgO symmetric stretching and formation34,50 and it helps in protecting alloy surfaces. All other peaks are related to the probe (417, 450, 577, 750 cm− 1). This ensures the formation of phosphate coating especially at high concentrations and decrease of carbonate peaks at 277 and 1097 cm− 1 All of these are due to the change of pH of the solution as given in Table 4.

The alteration of pH with time of a solution comprising dolomite in suspension at various concentrations of phosphoric acid are presented in Fig. 12. Outcomes display that the pH of the solution enlarged quickly in the first minute after adding of the mineral and then stays constant, slightly rises or slightly falls. This is due to adsorption precipitation of the hydrolysis products. Also, pH decreases for all sizes for dolomite with increasing phosphoric acid concentration.

Phosphate minerals are sparingly soluble51,52 and adding of dolomite to the phosphoric acid solution increases the pH, indicating a proton consumption by the dolomite surface and/or by dolomite dissolution products. Change of pH (∆pH = pH15 min – pHt=0, without mineral) given in Fig. 13, or proton consumption on dolomite is maximum at 10− 3 M and then decreases at 0.1 M followed by sharp minimization. It is the sharper reduction or faster dissolution for fine particles than coarser ones owing to the higher area and more passivation of fine particles. Also, proton consumption on dolomite is reduced by enlarging phosphoric acid concentration due to passivation of the dolomite surface by forming Mg3(PO4)2 or Ca3(PO4)2.

Here are SEM images in Fig. 14A-D for samples of Dolomite before and after treatment with phosphoric acid solution. Figure 14A is for pure dolomite without any treatment. Figure 14B is for dolomite mineral after immersion in 0.1 M phosphoric acid for 1 h and doing Raman spectroscopy experiment and then filtration to see the film of Ca or Mg phosphate. The film started to be more porous in 0.25 M concentration (Fig. 14C) and with the highest porosity at 0.5 M concentration (Fig. 14D). These are the same results obtained on the surface of Ti alloy Fig. 2A-C. They confirmed Raman spectroscopy results that the intensity is higher with increasing acid concentration owing to increasing film porosity and thickness. Thus, the porosity decreases the film impedance, however, still a good porous thick film that protects the alloy surface from corrosion.

Potentiodynamic polarization measurements

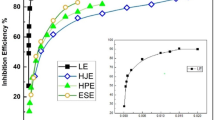

To confirm further the EIS results, SEM images and Raman spectroscopy experiments, potentiodynamic polarization technique is utilized to study the Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in H3PO4 acid solution of different concentrations (0.001-0.5 M) without and with 3% dolomite as represented in Figs. 15 and 16, respectively.

The corrosion potential (Ecorr) moves towards more negative potential as the concentration of the acid growths (Fig. 15). In addition, corrosion current density (Icorr) increased with growing acid concentration. It is clear from Fig. 15 that the addition of 3% dolomite leads to a decrease in the current density value. This means that dolomite inhibitor lowering the corrosion and hydrogen evolution rate by decreasing the cathodic branch protecting the surface due to good adsorption of dolomite on Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in H3PO4 acid.

The corrosion inhibition efficiency IE % of the Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid of different concentrations (0.001-0.5 M) containing 3% dolomite were calculated from corrosion current densities value in Table 5 using the following Eq. (5).

Where \({\text{i}}_{{{\text{corr}}^{{\underline{{{0}}} }} }}\) and icorr are the corrosion current densities for the Ti-6Al-4 V alloy without and/or with the dolomite inhibitor, respectively43,45. The corrosion parameters derived from the polarization curves such as corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (Icorr), and inhibition efficiency IE% were recorded in Table 5.

It was deduced that the highest IE% is 94.3% at 0.01 M and then decreased at higher concentrations but it is all nearly good at all concentrations. This is due to at 0.01 M, the film porosity is the lowest with the more positive potential. Also, due to the more adsorption of dolomite mineral. Thus, dolomite mineral works well as an environmental inhibitor. However, at higher concentration diffusion mechanism changed the film to be more porous, so this decreases the inhibition efficiency with increasing aggressive acid concentration. The inhibitor seems to affect mainly on the anodic branch and so it is an anodic type inhibitor.

FTIR analysis for phosphoric acid without and with 3% dolomite

The Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) are shown in Fig. 17, and were recorded to understand the chemical and molecular interactions between 0.5 M phosphoric acid and 3% dolomite. It is clear that after adding dolomite, there are new bands at 894, 748, 540 cm− 1 due to magnesium phosphate (struvite, Cattiite, Bobierrite; respectively) formation34,52. Other bands at 1111 and 1419 cm− 1 are due to carbonates. Also, all bands higher than 1600 cm− 1 are due to H-O-H bending or stretching. This confirms calcium or magnesium phosphate film formation on reaction between phosphoric acid solution and 3% dolomite.

Finally, all results obtained using all techniques and analyses ensured the excellent protective behavior of dolomite inhibitor for Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid of different concentrations (0.001-0.5 M) and considered as a novel natural, low cost and widely available material used in industrial applications.

Conclusions

Based on the results of potentiodynamic polarization and EIS measurements, the following conclusions are drawn in this study:

-

The electrochemical corrosion resistance of the Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid increases with immersion time and is the highest at 0.01 M phosphoric acid.

-

The corrosion resistance of Ti-6Al-4 V alloy in phosphoric acid shows that dolomite mineral behaves as an effective inhibitor and increases the corrosion resistance of the alloy by protecting it from corrosive medium and forming a protective film on the alloy surface.

-

It was found that the inhibition efficiency of dolomite, from polarization technique after adding to water or phosphoric acid, is 92.0% in water, 92.8% at 0.001 M, 94.3% at 0.01 M, 85.8% at 0.1 M, 85.7% at 0.25 M and 85.6% at 0.5 M with the same trend of impedance values obtained from EIS technique.

-

This confirms well that dolomite rock material is an effective inhibitor that works with adsorption mechanism at low aggressive medium and converts to diffusion especially at high concentration of phosphoric acid.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. (Amany M. Fekry)

References

Prando, D. et al. Corrosion of titanium: Part 1: Aggressive environments and main forms of degradation. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 15, e291–e302 (2017).

Fekry, A. M., Filippova, I. V., Medany, S. S., Abdel-Gawad, S. A. & Filippov, L. O. Use of a natural rock material as a precursor to inhibit corrosion of Ti alloy in an aggressive phosphoric acid medium. Sci. Rep. 14, 9807 (2024).

Zieliński, A. & Sobieszczyk, S. Corrosion of titanium biomaterials, mechanisms, effects and modelisation. Corros. Rev. 26, 1–22 (2008).

Singh, V. B. & Hosseini, S. M. A. Corrosion behaviour of Ti-6Al-4V in phosphoric acid. J. Appl. Electrochem. 24, 250–255 (1994).

Hosseini, S. M. A., Salari, M. & Quanbari, M. Electrochemical behavior of Ti–alloy in the mixture of formic and phosphoric acid in the presence of organic compound. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2, 935–946 (2007).

Ghoneim, A. A., Mogoda, A. S., Awad, K. A. & Heakal, F. E.-T. Electrochemical studies of titanium and its Ti–6Al–4V alloy in phosphoric acid solutions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 7, 6539–6554 (2012).

Poondla, N., Srivatsan, T. S., Patnaik, A. & Petraroli, M. A study of the microstructure and hardness of two titanium alloys: Commercially pure and Ti–6Al–4V. J. Alloys Compd. 486, 162–167 (2009).

Owen, E. L., May, R. C., Beck, F. H. & Fontana, M. G. Dissolution of Ti-6Al-4V at cathodic potentials in 5 N HCl. Corrosion 28, 292–295 (1972).

de Assis, S. L., Wolynec, S. & Costa, I. Corrosion characterization of titanium alloys by electrochemical techniques. Electrochim. Acta. 51, 1815–1819 (2006).

Ameer, M. A. & Fekry, A. M. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by natural product compound. Prog Org. Coat. 71, 343–349 (2011).

Chen, X., Chen, Q., Guo, F., Liao, Y. & Zhao, Z. Extraction behaviors of rare-earths in the mixed sulfur-phosphorus acid leaching solutions of scheelite. Hydrometallurgy 175, 326–332 (2018).

Singh, V. B. & Gupta, A. Dissolution and passivation of nickel-free austenitic stainless steel in concentrated acids and their mixtures. Corrosion 57, 43–51 (2001).

Contu, F., Elsener, B. & Böhni, H. Serum effect on the electrochemical behaviour of titanium, Ti6Al4V, and Ti6Al7Nb alloys in sulphuric acid and sodium hydroxide. Corros. Sci. 46, 2241–2254 (2004).

Mandry, M. J. & Rosenblatt, G. The effect of fluoride ion on the anodic behavior of titanium in sulfuric acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 119, 29 (1972).

Fekry, A. M. & Ameer, M. A. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic media using newly synthesized heterocyclic organic molecules. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 35, 7641–7651 (2010).

Ameer, M. A. & Fekry, A. M. Inhibition effect of newly synthesized heterocyclic organic molecules on corrosion of steel in alkaline medium containing chloride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 35, 11387–11396 (2010).

Yang, G., He, P. & Qu, X. P. Inhibition effect of glycine on molybdenum corrosion during CMP in alkaline H₂O₂-based abrasive-free slurry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 427, 148–155 (2018).

Araújo Macedo, R. G., Nascimento Marques, N. & Tonholo, J. do & de Carvalho Balaban, R. Water-soluble carboxymethylchitosan used as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in saline medium. Carbohydr. Polym. 205, 371–376 (2019).

Hamadi, L., Mansouri, S., Oulmi, K. & Kareche, A. The use of amino acids as corrosion inhibitors for metals: A review. Egypt. J. Pet. 27, 1157–1165 (2018).

Fekry, A. M. Electrochemical behavior of a novel nano-composite coat on Ti alloy in phosphate buffer solution for biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 6, 20276–20285 (2016).

Hosseini, S. M. A. & Singh, V. B. Active-passive behaviour of titanium and titanium alloy (VT-9) in sulphuric acid solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 33, 63–71 (1993).

Lin, K. & Zheng, T. Long-term corrosion behavior of low carbon steel bars embedded in building concrete: Effect of silica fume and dolomite powder as partial replacements of Portland cement. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 15, 12329–12338 (2020).

Log, T. et al. Scale and corrosion control with combined dolomite/calcite filter. Water Sci. Technol. 49, 137–144 (2004).

Williams, R. L., Brown, S. A. & Merritt, K. Electrochemical studies on the influence of proteins on the corrosion of implant alloys. Biomaterials 9, 181–186 (1988).

Ayoub, G. M., Kalinian, H. & Zayyat, R. Efficient phosphate removal from contaminated water using functional raw dolomite powder. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–15 (2019).

Ashraf, M., Zafar, I. Z., Ansari, T. M. & Ahmad, F. Selective leaching kinetics of calcareous phosphate rock in phosphoric acid. J. Appl. Sci. 5, 1722–1727 (2005).

Filippov, L. O., Duverger, A., Filippova, I. V. & Kasaimi, H. Selective flotation of silicates and Ca-bearing minerals: The role of non-ionic reagent on cationic flotation. Min. Eng. 36, 314–328 (2012).

Filippova, I. V., Filippov, L. O., Duverger, A. & Severov, V. V. Synergetic effect of a mixture of anionic and nonionic reagents: Ca mineral contrast separation by flotation at neutral pH. Min. Eng. 66–68, 144–152 (2014).

Filippov, L. O., Kaba, O. B. & Filippova, I. V. Surface analyses of calcite particles reactivity in the presence of phosphoric acid. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 2117–2125 (2019).

Kaba, O. B., Filippov, L. O., Filippova, I. V. & Badawi, M. Interaction between fine particles of fluorapatite and phosphoric acid unraveled by surface spectroscopies. Powder Technol. 382, 368–377 (2021).

Filippov, L. O., Kaba, O. B., Filippova, I. V. & Fornasiero, D. In-situ study of the kinetics of phosphoric acid interaction with calcite and fluorapatite by Raman spectroscopy and flotation. Min. Eng. 162, 106729 (2021).

Filippov, L. O., Filippova, I. V., Kaba, O. B. & Fornasiero, D. Investigation of the effect of phosphoric acid as an acidic medium in flotation separation of dolomite from magnesite. Min. Eng. 198, 108079 (2023).

Liua, C., Zhang, W. & Lid, H. Selective flotation of apatite from calcite using 2-phosphonobutane-1,2,4-tricarboxylic acid as depressant. Min. Eng. 136, 62–65 (2019).

Filippov, L. O., Filippova, I. V. & Fekry, A. M. Evaluation of interaction mechanism for calcite and fluorapatite with phosphoric acid using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 2316–2325 (2024).

Bhat, R. S., Balakrishna, M. K., Parthasarathy, P. & Hegde, A. C. Structural properties of Zn-Fe alloy coatings and their corrosion resistance. Coatings 13, 772 (2023).

Bhat, R. S., Nagaraj, P. & Priyadarshini, S. Zn–Ni compositionally modulated multilayered alloy coatings for improved corrosion resistance. Surf. Eng. 37, 755–763 (2021).

Bhat, R. S., Shetty, S. M. & Kumar, N. A. Electroplating of Zn-Ni alloy coating on mild steel and its electrochemical studies. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 30, 8188–8195 (2021).

Bhat, R. S., Venkatakrishna, K. & Hegde, A. C. Surface structure and electrochemical behavior of zinc-nickel anti-corrosive coating. Adv. Electrochem. Eng. 2023, 702328. (2023).

Bhat, R. S. Fabrication of multi-layered Zn-Fe alloy coatings for better corrosion performance. IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.99630 (2021).

Fekry, A. M. & El-Sherif, R. M. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of magnesium and titanium alloys in simulated body fluid. Electrochim. Acta. 54, 7280–7285 (2009).

Hernández, H. H. et al. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS): A review study of basic aspects of the corrosion mechanism applied to steels. Chapter in IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94470 (2020).

Nasr, A., Abdel Gawad, S. & Fekry, A. M. A sensor for monitoring the corrosion behavior of orthopedic drug calcium hydrogen phosphate on a surgical 316L stainless steel alloy as implant. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros.. 6, 1–10 (2020).

Abdel Gawad, S., Nasr, A., Fekry, A. M. & Filippov, L. O. Electrochemical and hydrogen evolution behaviour of a novel nano-cobalt/nano-chitosan composite coating on a surgical 316L stainless steel alloy as an implant. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 46, 18233–18241 (2021).

Berninger, U. N., Saldi, G. D., Jordan, G., Schott, J. & Oelkers, E. H. Assessing dolomite surface reactivity at temperatures from 40 to 120°C by hydrothermal atomic force microscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 199, 130–142 (2017).

Medany, S. S., Ahmad, Y. H. & Fekry, A. M. Experimental and theoretical studies for corrosion of molybdenum electrode using streptomycin drug in phosphoric acid medium. Sci. Rep. 13, 4827 (2023).

Shashkova, I. L., Kitikova, N. V., Rat’ko, A. I. & D’yachenko, A. G. Preparation of calcium and magnesium hydrogen phosphates from natural dolomite and their sorptive properties. Inorg. Mater. 36, 826–827 (2000).

El-Hafez, G. M. A., Helal, N. H., Mohammed, H. H., Fekry, A. M. & Filippov, L. O. Adsorption and corrosion behavior of polyacrylamide and polyvinylpyrrolidone as green coatings for Mg–Al–Zn–Mn alloy: Eexperimental and computational studies. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros.. 8, 59 (2022).

Hussein, M. S. & Fekry, A. M. Effect of fumed silica/chitosan/poly (vinylpyrrolidone) composite coating on the electrochemical corrosion resistance of Ti–6Al–4V alloy in artificial saliva solution. ACS Omega. 4, 73–78 (2019).

El-Kamel, R. S., Ghoneim, A. A. & Fekry, A. M. Electrochemical, biodegradation and cytotoxicity of graphene oxide nanoparticles/polythreonine as a novel nano-coating on AZ91E mg alloy staple in gastrectomy surgery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 103, 109780 (2019).

Klasa, J. et al. An atomic force microscopy study of the dissolution of calcite in the presence of phosphate ions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 117, 115–128 (2013).

Lothenbach, B., Xu, B. & Winnefeld, F. Thermodynamic data for magnesium (potassium) phosphates. Appl. Geochem. 111, 104450 (2019).

Liu, X., Ruan, Y., Li, C. & Cheng, R. Effect and mechanism of phosphoric acid in the apatite/dolomite flotation system. Int. J. Miner. Process. 167, 95–102 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by European Union’s Horizon 2020 Fine Future project under grant agreement No. 821265 (Innovative technologies and concepts for fine particle flotation: unlocking future fine-grained deposits and Critical Raw Materials resources for the EU). Authors thank the Cairo University that greatly assisted the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.V Filippova, L.O. Filippov, S.S. Medany and A.M. Fekry; Data curation: I.V. Filippova, S.S. Medany and A.M. Fekry; Investigation: S.S. Medany and A.M. Fekry; Methodology: I.V. Filippova, S.S. Medany and A.M. Fekry; Project administration and Supervision: A.M. Fekry and L.O. Filippov; Validation: I.V. Filippova, L.O. Filippov, S.S. Medany and A.M. Fekry; Visualization: I.V. Filippova, S.S. Medany, A.M. Fekry and L.O. Filippov; Roles/Writing - original draft: A.M. Fekry; Writing - review & editing: S.S. Medany, A.M. Fekry, I. Filippova and L.O. Filippov.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Filippova, I.V., Fekry, A.M., Medany, S.S. et al. The interaction mechanism of dolomite mineral and phosphoric acid and its impact on the Ti alloy corrosion. Sci Rep 15, 4802 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87514-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87514-6