Abstract

This study investigates the impact of lithium-ion battery (LIB) design characteristics on recycling efficiency through a comprehensive mixed-methods research approach. The study employs structural equation modeling (SEM) and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) methodologies, analyzing data collected through systematic expert interviews with 15 industry professionals and structured surveys of 150 battery manufacturing and recycling facilities. Through rigorous qualitative and quantitative analysis, this research examines the relationships between design complexity, material diversity, connection methods, and recycling process efficiency and overall recycling performance. The research methodology combines in-depth interviews, expert consultations, and statistical analysis to ensure robust findings. Data sources include primary data from industry surveys, expert interviews, and secondary data from technical documentation and recycling facility reports, providing a comprehensive foundation for the analysis. The research compares recycling efficiency across different battery types, including traditional designs, cell-to-pack (CTP), and cell-to-body (CTB), utilizing multi-group analysis. Through life cycle cost analysis and environmental impact assessment, the study quantifies the potential economic and ecological benefits of optimized designs. Results indicate that while optimized LIB designs may increase initial production costs, they significantly enhance recycling efficiency, reduce total lifecycle costs, and minimize environmental impacts. SEM analysis reveals that design characteristics indirectly influence overall recycling performance by affecting recycling process efficiency. Multi-group analysis demonstrates the superior recyclability of CTP and CTB designs compared to traditional configurations. The study also evaluates the improvement potential for recycling efficiency across various materials, providing a basis for optimizing recycling strategies. This research offers valuable insights for battery design, recycling technology innovation, and policy formulation, emphasizing the importance of incorporating recyclability considerations in LIB development. It contributes significantly to advancing the energy storage industry towards a circular economy model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid proliferation of electric vehicles (EVs) and portable electronic devices has led to an unprecedented surge in the production and consumption of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). While these energy storage systems play a crucial role in the transition towards a low-carbon economy, they also present significant end-of-life challenges. The increasing volume of spent LIBs has raised concerns about resource depletion, environmental pollution, and waste management, necessitating the development of efficient recycling strategies. However, the complexity of modern LIB designs often hinders recycling efforts, highlighting the need for a holistic approach that considers the entire life cycle of these batteries.

Recent studies have extensively explored the application of Life Cycle Assessment in evaluating LIB environmental impacts. Darling & Gaustad1 conducted a comprehensive LCA focusing on the financial viability of EV battery recycling, highlighting the importance of design optimization for cost reduction. Rey & Alvarez2 specifically examined the environmental impacts of graphite recycling from spent LIBs, emphasizing material recovery efficiency. Furthermore, Lee & Wang3 assessed the environmental implications of specific cathode material (LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2) recycling, providing valuable insights into material-specific recovery challenges. These studies collectively demonstrate the growing importance of lifecycle thinking in battery design and recycling.

The application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in battery recycling research has also gained traction. Xu & Liang4 employed SEM to analyze the driving mechanisms of power battery recycling systems, demonstrating correlations between design parameters and recycling outcomes. Zhang & He5 further utilized this methodology to examine the relationships between design characteristics and recycling efficiency, finding significant direct and indirect effects. These studies have established SEM as a valuable tool for understanding complex relationships in battery recycling systems.

Product design has emerged as a critical factor influencing the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of LIB recycling processes. Previous research has investigated various aspects of LIB design’s influence on recycling efficiency. Peters & Baumann6 examined how battery architecture affects material recovery rates, finding that modular designs improved recyclability by 15–20%. Bicer & Dincer7 analyzed the environmental impacts of different battery designs, demonstrating that simplified structures reduced recycling energy consumption by up to 30%. The intricate structures and diverse material compositions of contemporary LIBs, while optimized for performance and energy density, often complicate disassembly and material recovery. For instance, the cell-to-pack (CTP) and cell-to-body (CTB) technologies, pioneered by companies like BYD, have revolutionized EV battery integration but inadvertently increased recycling challenges due to extensive use of adhesives and integrated designs.

The relationship between design characteristics and recycling efficiency has been explored through different methodological approaches. Swain8 conducted experimental studies on various battery designs, while Dai & Kelly9 employed statistical modeling to quantify design impacts. However, a comprehensive framework incorporating both life cycle impacts and structural relationships between design features and recycling outcomes remains lacking. This exemplifies the tension between advancing battery technology and ensuring recyclability, underscoring the importance of considering end-of-life scenarios during the initial design phase.

The concept of Design for Recycling (DfR) has gained traction in recent years, advocating for the incorporation of recyclability considerations into product development. Zhang & Shaffer10 investigated the implementation of DfR principles in battery manufacturing, identifying key design parameters that influence recycling efficiency. Wang & Li11 further analyzed the economic implications of DfR approaches, demonstrating potential cost savings through improved recyclability. However, implementing DfR principles in LIB design is not straightforward, as it may conflict with other desirable attributes such as energy density, safety, and cost-effectiveness. This complex interplay of factors necessitates a comprehensive analysis to quantify the impacts of various design decisions on recycling efficiency and overall life cycle costs.

While existing studies have made significant contributions to understanding LIB recycling, several crucial gaps remain:

-

1.

Previous research has typically examined design features and recycling efficiency separately, without a unified framework for analyzing their relationships.

-

2.

The indirect effects of design characteristics on recycling performance through process efficiency have not been adequately quantified.

Comparative analyses of traditional and innovative designs (CTP, CTB) lack systematic evaluation of their lifecycle implications

This study aims to bridge these gaps by investigating the influence of design characteristics on recycling efficiency through a combined LCA-SEM approach. By quantifying the direct and indirect effects of various design parameters on economic, environmental, and technical aspects of recycling processes, this research seeks to provide actionable insights for battery manufacturers, recyclers, and policymakers. The findings are expected to contribute to the development of more sustainable LIB designs that balance performance requirements with recyclability, ultimately supporting the transition towards a circular economy in the energy storage sector.

The innovative integration of LCA and SEM methodologies in this study offers a unique perspective on the challenges and opportunities in LIB recycling. By considering both the technical aspects of battery design and the broader implications for recycling systems, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing recycling efficiency. The results of this study have the potential to inform design strategies, recycling technologies, and policy frameworks, fostering a more sustainable approach to LIB production and management throughout their life cycle.

Research methods

Study design

The research design for this study adopts an innovative mixed-methods approach by integrating Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the impact of lithium-ion battery (LIB) design characteristics on recycling efficiency. This methodology combines the comprehensive life cycle perspective of LCA with the advanced statistical capabilities of SEM, enabling a nuanced analysis of the complex relationships between design parameters and recycling outcomes.

The study employs a sequential exploratory design, beginning with qualitative data collection through expert interviews (n = 15) followed by quantitative surveys (n = 150) of battery manufacturing and recycling facilities. The sampling strategy utilized a stratified random approach to ensure representation across different facility sizes, geographical locations, and technological capabilities. Survey administration was conducted via a secure online platform, with follow-up protocols to ensure high response rates.

Data collection proceeded in three distinct phases. First, extensive literature review and preliminary expert consultations informed the development of interview protocols and survey instruments. Second, semi-structured interviews with industry experts provided rich qualitative insights into the relationships between battery design and recycling efficiency. Third, structured surveys gathered quantitative data on specific design parameters, recycling processes, and efficiency indicators.

The quantitative phase employed a comprehensive survey instrument developed based on qualitative findings and validated through pilot testing. The survey achieved a response rate of 78%, with respondents representing diverse segments of the LIB industry. Data analysis integrated thematic analysis of interview transcripts with statistical modeling of survey responses, employing both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis before proceeding to structural equation modeling.

This integrated research design enables triangulation of findings through multiple data sources and analytical approaches. The combination of qualitative insights with quantitative measurements provides a robust foundation for understanding the complex relationships between LIB design characteristics and recycling efficiency. Furthermore, this approach allows for both depth in understanding technical processes and breadth in analyzing industry-wide patterns.

The study population encompassed lithium-ion battery manufacturers, recycling facilities, and related stakeholders across major industrial regions in China. Drawing from the National Battery Industry Database, the sampling frame consisted of 450 organizations, including 200 battery manufacturers, 150 recycling facilities, and 100 supporting enterprises. The determination of sample size was guided by the model’s complexity, featuring 15 observed variables and 3 latent constructs. Following the N: q rule (ratio of cases to free parameters) with a recommended minimum 10:1 ratio, and accounting for 33 free parameters in our model, a minimum sample size of 330 cases was required. To ensure adequate statistical power and account for potential non-responses, we targeted a sample size of 400 participants.

A stratified random sampling approach was implemented to ensure comprehensive representation across organization types, geographic regions, and enterprise scales. The population was initially stratified based on organization type (manufacturers, recyclers, suppliers) and geographic location (Eastern, Southern, Northern, and Western China), followed by random selection within each stratum using computer-generated sequences. The sampling process included rigorous verification of organizational eligibility and implementation of replacement sampling for non-responsive units. This methodology yielded 368 valid responses, achieving a response rate of 92% and exceeding the minimum required sample size for statistical power of 0.95.

Data collection proceeded through a mixed-method approach, primarily utilizing structured online questionnaires supplemented by follow-up telephone interviews and selective on-site visits for validation purposes. The data quality assurance protocol included pilot testing with 30 organizations, continuous monitoring of response patterns, and systematic handling of missing data through Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation. Outliers were identified and evaluated using Mahalanobis distance calculations. To address potential sampling bias and ensure model robustness, we conducted sensitivity analyses through bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations, multi-group analyses across different organizational categories, and cross-validation with hold-out samples. The model’s stability was further verified through measurement invariance testing, residual pattern analysis, and careful assessment of modification indices.

This comprehensive sampling and validation approach provided a robust foundation for the subsequent structural equation modeling analysis, ensuring both statistical rigor and practical relevance in examining the relationships between battery design characteristics and recycling efficiency. The achieved sample size and sampling methodology support generalizable findings while maintaining the statistical power necessary for complex model estimation.

The process begins with extensive data collection on LIB design features, recycling processes, and efficiency indicators through literature review, expert interviews, and industry surveys. This data informs a detailed LCA focused on the end-of-life stage of LIBs, quantifying environmental impacts and resource efficiency across various recycling scenarios. Key variables related to battery design and recycling efficiency are then identified and operationalized, forming the foundation for the SEM model development. The structural equation model hypothesizes relationships between design characteristics and recycling efficiency measures, which are subsequently estimated and validated using the collected data. Rigorous analysis and interpretation of the model results, including examination of direct and indirect effects and sensitivity analyses, provide insights into the complex interplay between design choices and recycling outcomes. The study culminates in applying the model to specific LIB designs, such as traditional versus cell-to-pack (CTP) or cell-to-body (CTB) configurations, demonstrating practical implications for sustainable battery design and recycling strategies.

As shown in Fig. 1, the research design framework integrates data analysis, modeling, and practical application to assess LIB recycling efficiency.

Data collection

Questionnaire design

A structured questionnaire was developed to gather quantitative data on LIB design features and recycling processes. The questionnaire was designed based on an extensive literature review and preliminary expert consultations. As shown in Table 1, it consists of five main sections: (1) respondent demographics, (2) LIB design characteristics, (3) recycling process details, (4) efficiency indicators, and (5) perceived challenges and opportunities. The questionnaire employs a mix of Likert-scale items, multiple-choice questions, and open-ended responses to capture both quantitative and qualitative data. To ensure validity and reliability, the questionnaire underwent pilot testing with a small group of industry professionals, and refinements were made based on their feedback. The final questionnaire was distributed to a targeted sample of LIB manufacturers, recycling facilities, and research institutions using an online survey platform.

Expert interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 experts representing diverse backgrounds in the lithium-ion battery (LIB) industry. The experts were selected based on their professional experience, technical expertise, and industry roles, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the battery lifecycle from design to recycling. The expert panel comprised five battery design specialists from major manufacturers and technology firms, with an average industry experience of 13.5 years and extensive expertise in CTP and CTB technologies. These design specialists provided crucial insights into the evolution of battery architectures and their implications for end-of-life management.

The panel also included four recycling process experts, including facility operators and technical directors with an average of 9 years of experience in various recycling technologies, particularly hydrometallurgical processes and mechanical pre-treatment methods. Their practical experience in handling different battery designs provided valuable perspectives on the challenges and opportunities in recycling processes. Three academic researchers, including university professors in materials science and a research institute director, contributed theoretical insights and research-based perspectives on battery materials and recycling technologies. Their expertise in circular economy principles and industry-academic collaboration enhanced the study’s theoretical foundation.

Additionally, three policy and standards experts, including environmental policy consultants and an industry standards specialist, provided crucial insights into regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements affecting battery design and recycling practices. Their expertise in international policy and recycling standards helped contextualize the technical aspects within broader regulatory and policy frameworks.

The interviews followed a structured protocol exploring key areas including technical aspects of battery design influencing recyclability, current challenges in recycling processes, economic viability of different recycling approaches, environmental impact considerations, policy implications, and future trends in battery recycling. Each interview session, lasting approximately 60–90 min, was conducted either in person or via video conferencing, allowing for in-depth exploration of complex technical and operational issues.

The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a rigorous thematic analysis approach to identify key patterns and relationships between battery design characteristics and recycling efficiency. The analysis revealed significant insights into how design decisions influence recycling outcomes, which subsequently informed the development of the quantitative survey instrument. Follow-up consultations were conducted when necessary to clarify technical details or expand on specific points, ensuring accuracy and comprehensiveness of the collected data.

The qualitative insights from these expert interviews proved instrumental in bridging the gap between theoretical frameworks and industry practice, providing a robust foundation for the development of the structural equation model and the interpretation of quantitative results. The diverse expertise of the interview participants enabled a comprehensive understanding of the complex interrelationships between battery design characteristics and recycling efficiency.

Case study data collection

To complement the survey and interview data, detailed case studies of specific LIB designs were conducted. This involved collecting technical specifications, lifecycle data, and recycling performance metrics for three distinct LIB configurations: a traditional design, a cell-to-pack (CTP) design, and a cell-to-body (CTB) design. As shown in Table 2, technical specifications were primarily sourced from manufacturer documentation, yielding information on battery structure, material composition, and energy density. Lifecycle data, including resource consumption, emissions, and lifespan, were extracted from LCA reports and industry databases. Recycling performance metrics, such as disassembly time, material recovery rates, and energy consumption, were obtained from facility reports and on-site measurements.

Variable measurement

The measurement of variables in this study focuses on quantifying key aspects of lithium-ion battery (LIB) design and recycling efficiency. Variables were selected based on their relevance to the research objectives and their ability to be reliably measured across different battery designs and recycling processes. Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of these key variables and their measurement approaches.

Design characteristics were operationalized through a set of measurable indicators reflecting the complexity, material composition, and structural attributes of LIBs. As shown in Table 3, these include structural complexity, material diversity, and disassembly difficulty. Each indicator was assigned a numerical scale or categorical classification to enable quantitative analysis.

Recycling efficiency variables were categorized into economic, environmental, and technical dimensions, as detailed in Table 3. Economic efficiency was measured through indicators such as recycling cost per unit weight and recovered material value. Environmental efficiency was quantified using metrics like energy consumption during recycling and percentage of materials recovered. Technical efficiency indicators included disassembly time, purity of recovered materials, and process yield.

To ensure consistency and comparability, standardized measurement protocols were developed for each variable, as outlined in Table 3. Where direct measurements were not feasible, proxy indicators or expert assessments were used. All measurements were documented with their associated uncertainties and measurement methods to support the reliability of subsequent analyses.

Table 3 illustrates the comprehensive set of variables and their respective measurement approaches and scales. This multifaceted view of the relationship between LIB design and recycling efficiency, as presented in Table 3, enables robust statistical analysis and modeling in subsequent stages of the research. The structured approach to variable measurement, as detailed in Table 3, provides a solid foundation for examining the complex interplay between battery design characteristics and recycling outcomes.

Data analysis methods

Life cycle assessment (LCA)

The LCA methodology follows ISO 14,040 and 14,044 standards, focusing on the end-of-life stage of LIBs12,13. The functional unit is defined as 1 kg of spent LIB processed for recycling, following established methodologies in recent critical reviews14. The system boundary includes transportation, pre-treatment, and material recovery processes. The life cycle impact assessment utilizes the ReCiPe 2016 method, considering midpoint indicators such as global warming potential (GWP) and resource depletion potential (RDP). The inventory analysis is conducted using SimaPro software, with data sourced from the ecoinvent database and primary data collection.

The environmental impact score (EIS) for each recycling scenario is calculated using the following equation:

Where \({w_i}\) is the weighting factor for impact category i, \({I_i}\) is the impact score for category i, \({I_{i,min}}\) and \({I_{i,max}}\) are the minimum and maximum impact scores across all scenarios for category i.

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

The development of the conceptual framework (Fig. 2) followed a systematic approach combining theoretical analysis and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Initially, a comprehensive literature review identified potential factors affecting LIB recycling efficiency, yielding 42 preliminary variables. These variables were then refined through expert interviews (n = 15) and pilot surveys (n = 30), resulting in an initial pool of 25 measured variables.

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal axis factoring with oblique rotation (Promax) on the pilot data. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.89, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 3245.67, p < 0.001), confirming the appropriateness of factor analysis. The initial EFA revealed three distinct factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, collectively explaining 78.3% of the total variance:

-

1.

Design Characteristics (DC): Eight variables loaded significantly (> 0.5) on this factor, including structural complexity, material diversity, and connection methods.

-

2.

Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE): Seven variables showed significant loadings, encompassing energy efficiency, material recovery rates, and process optimization metrics.

-

3.

Overall Recycling Performance (ORP): Six variables demonstrated significant loadings, including economic viability, environmental impact, and resource conservation indicators.

Variables with cross-loadings (> 0.4) or low communalities (< 0.5) were eliminated, resulting in a refined set of 15 variables. The theoretical relationships between these factors were then established through systematic literature analysis and validated through expert consultation, leading to the hypothesized structural relationships depicted in Fig. 2. This combined empirical-theoretical approach ensured that the conceptual model was both statistically sound and theoretically grounded.

The final measurement model demonstrated good fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis (CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.058), supporting the construct validity of the proposed framework. The path relationships in the conceptual model were further validated through preliminary structural equation modeling using the pilot data, providing initial support for the hypothesized relationships between design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance.

The SEM analysis is performed using the lavaan package in R. The model consists of latent variables representing design characteristics and recycling efficiency, with observed variables as indicators. The general form of the structural model is:

Where \(\eta\) is a vector of endogenous latent variables, \(\xi\) is a vector of exogenous latent variables, B and \(\Gamma\) are matrices of structural coefficients, \(\zeta\) is a vector of disturbances.

As shown in Table 4, the model fit is evaluated using four key indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). For each index, Table 4 provides thresholds for both good fit and acceptable fit. These criteria, as outlined in Table 4, guide the interpretation of the model’s adequacy in representing the underlying data structure.

Specifically, Table 4 indicates that for CFI and TLI, values ≥ 0.95 are considered good fit, while values ≥ 0.90 are deemed acceptable. For RMSEA, values ≤ 0.06 indicate good fit, and values ≤ 0.08 are acceptable. Similarly, for SRMR, values ≤ 0.08 suggest good fit, while values ≤ 0.10 are considered acceptable. These thresholds, as presented in Table 4, provide a standardized framework for evaluating the robustness of the structural equation model in this study.

As shown in Fig. 2, the conceptual SEM model illustrates the hypothesized relationships between battery design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance.

Quantification of design characteristics of lithium-ion battery products

Structural complexity index

The Structural Complexity Index (SCI) is developed to quantify the intricacy of lithium-ion battery (LIB) designs, focusing on aspects that influence recycling processes. This index incorporates multiple factors, including the number of components, their interconnectedness, and the diversity of materials used.

The SCI is calculated using the following formula:

Where \({N_c}\) represents the number of components (previously n), \({C_f}\) represents the connectivity factor, \({M_d}\) represents the material diversity factor, \({N_{max}}\), \({C_{max}}\), and \({M_{max}}\) are the maximum values observed in the sample.

The weighting factors (w1, w2, w3) were determined through a systematic analytical hierarchy process (AHP), incorporating comprehensive expert consultation with 15 industry professionals, including battery design engineers, recycling specialists, and academic researchers. The expert evaluation process considered multiple aspects of battery design and recycling, including the relative impact of each factor on recycling difficulty, cost implications, and technical feasibility of modifications. Through iterative consultation rounds, consensus was reached on the relative importance of each component in the overall complexity assessment.

To validate the robustness of these weights, comprehensive sensitivity analyses were conducted comparing results using equal weights (w1 = w2 = w3 = 1/3) against our weighted system. The analysis revealed that while weighting provides more nuanced evaluation of complexity factors, the fundamental conclusions about design optimization remain valid across different weighting scenarios. Specifically, the relative performance difference between traditional and optimized designs varied by less than 15% when comparing weighted and unweighted calculations, demonstrating the robustness of our findings. This consistency across different weighting schemes supports the reliability of our approach in quantifying battery design complexity and its impact on recycling efficiency.

The connectivity factor C is further defined as:

Where \({c_{ij}}\) is 1 if components i and j are directly connected, and 0 otherwise.

The material diversity factor M is calculated as:

Where K is the number of distinct materials, and \({p_i}\) is the proportion of material i in the battery by weight.

Table 5 details the symbols, weights, and descriptions for each SCI component. The number of components, as described in Table 5, represents the total count of distinct parts in the battery. The connectivity factor, outlined in Table 5, measures the degree of interconnections between components. The material diversity factor also presented in Table 5, is based on the Shannon diversity index of materials used in the battery.

The weighting factors for each component, as shown in Table 5, allow for adjusting the relative importance of each factor in the overall SCI calculation. This flexible approach, facilitated by the structure presented in Table 5, enables the SCI to be tailored to specific research focuses or industry priorities in assessing battery design complexity.

As shown in Fig. 3, the relationship between SCI components demonstrates how structural complexity varies with increasing number of components and material diversity.

Material diversity index

The Material Diversity Index (MDI) is a crucial metric for assessing the complexity of lithium-ion battery (LIB) compositions and their potential impact on recycling processes. This index quantifies the variety and distribution of materials within a battery, providing insights into the challenges associated with material separation and recovery. The MDI is calculated using a modified version of the Shannon diversity index (also known as Shannon-Wiener diversity index), which accounts for both the number of distinct materials and their relative proportions within the battery structure.

The formula for MDI is expressed as:

Where M represents the total number of distinct materials (previously n), \({p_i}\) represents the proportion of the i-th material, \({w_i}\) represents the weighting factor based on the material’s recyclability or economic value. The weighting factor \({w_i}\) is determined using a standardized scale ranging from 0.5 for materials that are difficult to recycle or have low value, to 1.5 for highly recyclable or valuable materials. This weighting system ensures that the MDI not only reflects the diversity of materials but also their significance in the recycling process. To normalize the MDI for comparison across different battery designs, a relative MDI (rMDI) is calculated by dividing the MDI by the natural logarithm of the total number of materials:

The rMDI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater material diversity and potentially more complex recycling processes. To illustrate the application of the MDI, consider a typical lithium-ion battery composition as shown in Table 6.

As shown in Fig. 4, the material composition and recyclability in LIBs illustrates the diversity of materials and their respective recovery potentials.

Connection complexity index

The Connection Complexity Index (CCI) is a novel metric designed to quantify the intricacy of interconnections within lithium-ion battery (LIB) structures, which significantly impacts the disassembly process during recycling. This index considers both the number and nature of connections between battery components, providing a comprehensive measure of the battery’s structural complexity. The CCI is calculated using the following formula:

Where n is the total number of components, \({c_{ij}}\) is a binary indicator (1 if components i and j are connected, 0 otherwise), \({w_{ij}}\) is a weight factor based on the connection type, \({d_{ij}}\) is the difficulty rating of separating the connection, and \({d_{max}}\) is the maximum difficulty rating in the system. The weight factor \({w_{ij}}\) varies based on the connection type: 1.0 for mechanical connections, 1.2 for adhesive bonds, and 1.5 for welded joints. The difficulty rating \({d_{ij}}\) ranges from 1 (easily separable) to 10 (extremely difficult to separate).

To normalize the CCI for comparison across different battery designs, a relative CCI (rCCI) is calculated:

Where \(CC{I_{max}}\) is the theoretical maximum CCI for a fully connected system with the most difficult separation type for all connections. The rCCI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater connection complexity and potentially more challenging disassembly processes.

The connection type weights for the Connection Complexity Index were derived through an empirically grounded methodology combining quantitative analysis of battery disassembly operations with expert evaluation. The research team analyzed data from 200 documented battery disassembly procedures, measuring critical parameters including disassembly time, tool requirements, labor intensity, and success rates. This comprehensive dataset provided the empirical foundation for weight determination.

The weight calculation methodology incorporated multiple factors through a systematic evaluation process. Mechanical connections, serving as the baseline, received a weight of 1.0. Adhesive bonds, requiring additional processing time and specialized tools, warranted an adjusted weight of 1.2 through cumulative factors including increased time requirements (+ 0.1), tool complexity (+ 0.05), and labor intensity (+ 0.05). Welded joints, presenting the greatest disassembly challenges, received a weight of 1.5, reflecting significant increases across all evaluation factors. The weighting system underwent extensive validation through cross-referencing with industry data and sensitivity analyses, demonstrating result variations below 10% across different scenarios.

Table 7 provides a detailed breakdown of sample connection types and their associated weight factors and difficulty ratings. As evident from Table 7, mechanical connections have the lowest weight (1.0) and the lowest difficulty range (1–5), indicating they are generally the easiest to separate. Adhesive bonds, as shown in Table 7, have a moderate weight (1.2) and a slightly higher difficulty range (3–8). Welded joints, according to Table 7, have the highest weight (1.5) and the highest difficulty range (6–10), reflecting their status as the most challenging type of connection to separate during the recycling process.

This structured approach to quantifying connection complexity, as detailed in Table 7, allows for a nuanced assessment of LIB designs in terms of their recyclability and disassembly challenges. The information provided in Table 7 is crucial for understanding how different connection types contribute to the overall complexity of battery structures and their implications for recycling processes.

As shown in Fig. 5, the Connection Complexity Index (CCI) heatmap visualizes complexity across battery components, with color intensity indicating CCI values and cell text showing connection types and difficulty ratings.

Modularity assessment

The Modularity Assessment Index (MAI) is a comprehensive metric designed to evaluate the degree of modularity in lithium-ion battery (LIB) designs, which significantly influences the efficiency of recycling processes. This index incorporates multiple factors, including the number of distinct modules, the ease of module separation, and the homogeneity of materials within modules. The MAI is calculated using the following formula:

Where N is the total number of modules, \({M_i}\) is the mass of module i, \({M_{max}}\) is the mass of the largest module, \({S_i}\) is the separation factor for module i, and \({H_i}\) is the material homogeneity factor for module i. The separation factor \({S_i}\) ranges from 0 (inseparable) to 1 (easily separable), while the homogeneity factor \({H_i}\) is calculated as:

Where K is the number of distinct materials in module i, and \({p_{ij}}\) is the proportion of material j in module i. This formulation ensures that modules with fewer, more homogeneous materials have higher \({H_i}\) values.

To provide a standardized measure, the Relative Modularity Index (RMI) is derived:

Where \(MA{I_{min}}\) and \(MA{I_{max}}\) are the theoretical minimum and maximum MAI values for the given battery design. The RMI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater modularity and potentially more efficient recycling processes.

Table 8 presents sample module characteristics for MAI calculation, illustrating how these factors are applied in practice. As shown in Table 8, four main modules of a typical LIB are considered: the Cell Stack, Battery Management System, Cooling System, and Casing. For each module, Table 8 provides key information including mass, separation factor, number of materials, and homogeneity factor.

The data in Table 8 demonstrates the variability in module characteristics that impact modularity. For instance, the Cell Stack, as indicated in Table 8, has the largest mass (10 kg) but a moderate separation factor (0.8) and homogeneity factor (0.65). In contrast, Table 8 shows that the Casing, while having a lower mass (5 kg), has the highest separation factor (0.95) and homogeneity factor (0.90), suggesting it may be the most modular component for recycling purposes.

This detailed breakdown in Table 8 provides crucial insights into how different components of an LIB contribute to its overall modularity, directly influencing recycling efficiency. The information presented in Table 8 serves as a valuable reference for understanding the practical application of the MAI and RMI in assessing LIB designs for recyclability.

As shown in Fig. 6, the bubble plot illustrates module characteristics and MAI components, with bubble size representing module mass and color indicating MAI component values.

Construction of recycling efficiency evaluation index system

Economic efficiency indicators

The Economic Efficiency Index (EcEI) for lithium-ion battery recycling processes is a comprehensive metric that quantifies the financial viability and economic performance of recycling operations. This index incorporates multiple factors including recycling costs, material recovery value, and process efficiency. The EcEI is calculated using the following formula:

Where \({R_v}\) is the total value of recovered materials, \({C_p}\) is the processing cost, \({E_p}\) is the process efficiency factor, and \({C_t}\) is the total cost including capital investment and operational expenses.

The process efficiency factor \({E_p}\) is defined as:

Where n is the number of recoverable materials, \({w_i}\) is the economic weight of material i, and \({R_i}\) is the recovery rate of material i.

To normalize the EEI for comparison across different recycling processes and battery types, a Relative Economic Efficiency Index (REEI) is calculated:

The REEI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater economic efficiency in the recycling process.

Table 9 presents sample economic parameters for LIB recycling, providing concrete values for key variables in the EcEI calculation. The total recovered material value is 2500/ton, while the processing cost is 1200/ton. The total cost, which includes both capital investment and operational expenses, is given as 2000/ton. Furthermore, Table 9 provides recovery rates for various materials crucial to the recycling process. Copper has the highest recovery rate at 95%, followed closely by cobalt at 90% and aluminum at 90%. Nickel and lithium have slightly lower recovery rates of 85% and 80% respectively. These values are essential for calculating the process efficiency factor and, subsequently, the Economic Efficiency Index (EEI). The high recovery rates for valuable materials like cobalt and copper suggest a potentially favorable economic outlook for LIB recycling processes.

As shown in Fig. 7, the stacked bar chart depicts material recovery values in LIB recycling, highlighting actual and potential recovery for different materials.This stacked bar plot illustrates the economic impact of material recovery rates in the LIB recycling process. The blue portion of each bar represents the actual recovered value, while the orange portion shows the potential value if recovery was 100% efficient. The percentage above each bar indicates the current recovery rate for each material. This visualization helps identify which materials contribute most significantly to the economic efficiency of the recycling process and where improvements in recovery rates could yield the greatest economic benefits.

Environmental efficiency indicators

The Environmental Efficiency Index (EEI) for lithium-ion battery recycling processes is a comprehensive metric that quantifies the environmental impact and sustainability of recycling operations. This index incorporates multiple factors including energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and resource conservation. The EEI is calculated using the following formula:

Where n is the number of environmental impact categories, \({w_i}\) is the weighting factor for impact category i, \({E_i}\) is the environmental impact of the recycling process for category i, and \({E_{i,ref}}\) is the reference environmental impact for category i (e.g., impact of primary production). The weighting factors are determined based on the relative importance of each environmental impact category, with \(\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{w_i}} =1\).

To account for the resource recovery aspect, a Resource Conservation Factor (RCF) is incorporated:

Where m is the number of recoverable materials, \({v_j}\) is the environmental value factor of material j, and \({R_j}\) is the recovery rate of material j. The final Environmental Efficiency Index is then calculated as:

\(EE{I_{final}}=EEI \cdot RCF\)

This formulation ensures that both the reduction of environmental impacts and the conservation of resources are considered in the assessment of recycling efficiency.

Table 10 presents the environmental impact categories and their corresponding weighting factors used in the EEI calculation. As shown in Table 10, five key impact categories are considered: Global Warming Potential, Energy Consumption, Water Depletion, Toxicity, and Resource Depletion.

Technical efficiency indicators

The Technical Efficiency Index (TEI) for lithium-ion battery recycling processes is a comprehensive metric that quantifies the technological performance and effectiveness of recycling operations. This index incorporates multiple factors including material recovery rates, process yield, energy efficiency, and time efficiency. The TEI is calculated using the following formula:

Where n is the number of key performance indicators, \({w_i}\) is the weighting factor for indicator i, \({R_i}\) is the recovery rate for material i, \({Y_i}\) is the process yield for step i, \({E_i}\) is the energy efficiency for process i, and \({T_i}\) is the time efficiency for process i. Each factor is normalized to a 0–1 scale, with 1 representing optimal performance. The weighting factors are determined based on the relative importance of each indicator, with \(\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{w_i}} =1\).

To account for the complexity of the recycling process, an additional Process Complexity Factor (PCF) is introduced:

Where S is the number of process steps. The final Technical Efficiency Index is then calculated as:

This formulation ensures that both the efficiency of individual processes and the overall complexity of the recycling system are considered in the assessment of technical efficiency.

Table 11 presents the key technical efficiency indicators and their corresponding weighting factors used in the TEI calculation. As shown in Table 11, four primary indicators are considered: Material Recovery Rate, Process Yield, Energy Efficiency, and Time Efficiency.

As shown in Fig. 8, the bubble plot visualizes the Technical Efficiency Index (TEI) for LIB recycling across different materials and process steps.This bubble plot provides a visual representation of the Technical Efficiency Index across different materials and process steps in the LIB recycling process. The size and color of each bubble indicate the TEI value, with larger and redder bubbles representing higher efficiency. This visualization helps identify the most efficient material-process combinations and areas where technical improvements could yield the greatest benefits in the recycling process.

Determination of index weights: analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is employed to determine the relative weights of the economic, environmental, and technical efficiency indicators in the overall assessment of lithium-ion battery recycling processes. This method involves pairwise comparisons of criteria to establish their relative importance. The process begins with the construction of a pairwise comparison matrix \(A=({a_{ij}})n \times n\), where\(aij\) represents the importance of criterion i relative to criterion j. The scale typically ranges from 1 to 9, where 1 indicates equal importance and 9 indicates extreme importance of one criterion over another.

The weight vector \(w={({w_1}, \ldots ,{w_n})^T}\) is then calculated by solving the eigenvalue problem:

where \({\lambda _{max}}\) is the maximum eigenvalue of A. The consistency of the pairwise comparisons is checked using the Consistency Ratio (CR):

where \(CI=\frac{{{\lambda _{max}} - n}}{{n - 1}}\) is the Consistency Index, and RI is the Random Index (a predefined value based on the matrix size). A CR value less than 0.1 is generally considered acceptable.

Table 12 presents the pairwise comparison matrix for the efficiency indicators used in this study. As shown in Table 12, three main indicators are considered: Economic, Environmental, and Technical. The values in Table 12 represent the relative importance of each indicator compared to the others.

This hierarchical tree diagram illustrates the structure of the decision problem and the relative weights of each criterion and sub-criterion as determined by the AHP. The size of each node represents its weight in the overall assessment. This visualization helps stakeholders understand the relative importance of different factors in evaluating the efficiency of LIB recycling processes, facilitating more informed decision-making and process optimization strategies.

Construction and analysis of structural equation modeling

Measurement model

The measurement model for the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis of lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency is designed to capture the relationships between latent variables and their observed indicators. This model comprises three main constructs: Design Characteristics (DC), Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE), and Overall Recycling Performance (ORP). Each construct is measured by multiple indicators, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of the recycling process. The measurement model is represented by the following equations:

For Design Characteristics (DC): \({X_i}={\lambda _{{x_i}}} \cdot DC+{\delta _i}\)

For Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE): \({Y_j}={\lambda _{{y_j}}} \cdot RPE+{\epsilon _j}\)

For Overall Recycling Performance (ORP): \({Z_k}={\lambda _{{z_k}}} \cdot ORP+{\zeta _k}\)

Where \({X_i}\), \({Y_j}\), and \({Z_k}\) are observed variables, \({\lambda _{{x_i}}}\), \({\lambda _{{y_j}}}\), and \({\lambda _{{z_k}}}\) are factor loadings, and \({\delta _i}\), \({\epsilon _j}\), and \({\zeta _k}\) are measurement errors. The covariance matrix of the latent variables is defined as:

Table 13 presents the latent variables and their corresponding indicators used in the SEM analysis. As shown in Table 13, each latent variable is measured by multiple observed indicators, providing a comprehensive representation of the complex constructs involved in LIB recycling efficiency.

The measurement equations specifying the relationships between latent variables and their indicators are formulated as follows:

For Design Characteristics (DC):

\({x_1}={\lambda _{x1}}(DC)+{\delta _1}\)

\({x_2}={\lambda _{x2}}(DC)+{\delta _2}\)

\({x_3}={\lambda _{x3}}(DC)+{\delta _3}\)

\({x_4}={\lambda _{x4}}(DC)+{\delta _4}\)

For Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE):

\({y_1}={\lambda _{y1}}(RPE)+{\varepsilon _1}\)

\({y_2}={\lambda _{y2}}(RPE)+{\varepsilon _2}\)

\({y_3}={\lambda _{y3}}(RPE)+{\varepsilon _3}\)

\({y_4}={\lambda _{y4}}(RPE)+{\varepsilon _4}\)

For Overall Recycling Performance (ORP):

\({y_5}={\lambda _{y5}}(ORP)+{\varepsilon _5}\)

\({y_6}={\lambda _{y6}}(ORP)+{\varepsilon _6}\)

\({y_7}={\lambda _{y7}}(ORP)+{\varepsilon _7}\)

where \(\lambda\) represents factor loadings, \(\delta\) and \(\varepsilon\) represent measurement errors for exogenous and endogenous variables respectively. The covariance matrix of measurement errors is assumed to be diagonal, indicating that measurement errors are uncorrelated. The factor loadings (\(\lambda\)) represent the strength and direction of the relationship between each latent variable and its respective indicators.

As shown in Fig. 9, the path diagram illustrates the measurement model for LIB recycling efficiency, depicting relationships between latent variables and their observed indicators. This path diagram illustrates the relationships between latent variables (represented by ovals) and their observed indicators (represented by rectangles). The arrows indicate the direction of influence from latent variables to their respective indicators. This measurement model forms the foundation for the subsequent structural model, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the factors influencing LIB recycling efficiency.

Structural model

The structural model in the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis of lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency delineates the causal relationships among latent variables. This model encompasses three primary latent constructs: Design Characteristics (DC), Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE), and Overall Recycling Performance (ORP). The relationships between these variables are represented by the following equations:

Where \({\gamma _{11}}\) and \({\gamma _{21}}\) are the direct effect coefficients of the exogenous latent variable (DC) on the endogenous latent variables (RPE and ORP), \({\beta _{21}}\) is the direct effect coefficient of the endogenous latent variable (RPE) on another endogenous latent variable (ORP), and \({\zeta _1}\) and \({\zeta _2}\) are structural error terms.

The total effect (TE) of Design Characteristics on Overall Recycling Performance can be calculated as:

As shown in Fig. 10, the structural model diagram illustrates the relationships between Design Characteristics, Recycling Process Efficiency, and Overall Recycling Performance in LIB recycling. This structural model diagram clearly illustrates the relationships between Design Characteristics, Recycling Process Efficiency, and Overall Recycling Performance. The arrows indicate the direction of causal relationships, while the annotated coefficients (\({\gamma _{11}}\), \({\gamma _{21}}\), \({\beta _{21}}\)) represent the strength of these relationships. Through this model, we can gain a deeper understanding of how LIB design directly and indirectly influences recycling efficiency, providing a crucial theoretical foundation for optimizing design and improving recycling performance.

Model fitting and correction

Model fitting and modification are crucial steps in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency analysis. The process begins with evaluating the initial model’s fit using various indices. The chi-square test statistic (χ²) is fundamental, assessing the discrepancy between the observed and model-implied covariance matrices:

where N is the sample size and \({F_{ML}}\) is the value of the fitting function for maximum likelihood estimation. However, χ² is sensitive to sample size, so additional fit indices are considered. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) compares the model to a baseline model:

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) assesses how well the model fits the population covariance matrix:

If the initial model fit is inadequate, modification indices (MI) guide potential improvements. The expected parameter change (EPC) for a fixed parameter θ is calculated as:

As shown in Fig. 11, the flowchart depicts the iterative process of model evaluation, modification, and re-evaluation for achieving a satisfactory fit in LIB recycling efficiency analysis. This iterative process of model evaluation, modification, and re-evaluation continues until a satisfactory fit is achieved, balancing statistical fit with theoretical soundness. The final model provides a robust framework for understanding the complex relationships in LIB recycling efficiency.

Analysis of direct, indirect and total effects

The analysis of direct, indirect, and total effects in the Structural Equation Model (SEM) for lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency provides a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance. Direct effects represent the immediate impact of one variable on another, while indirect effects capture the influence mediated through intervening variables. The total effect is the sum of direct and indirect effects.

In our model, the direct effect of Design Characteristics (DC) on Overall Recycling Performance (ORP) is represented by \({\gamma _{21}}\), while the indirect effect through Recycling Process Efficiency (RPE) is calculated as the product of \({\gamma _{11}}\) and \({\beta _{21}}\). The total effect is thus:

To standardize these effects for comparison, we use the formula:

where \(S{D_{IV}}\) and \(S{D_{DV}}\) are the standard deviations of the independent and dependent variables, respectively.

The significance of these effects can be assessed using bootstrapped confidence intervals:

where \(S{E_{bootstrap}}\) is the standard error of the effect estimate derived from bootstrap resampling.

Table 14 presents the results of the direct, indirect, and total effects analysis for the key paths in our structural equation model. As shown in Table 16, three critical paths are examined: DC → RPE, DC → ORP, and RPE → ORP.

As shown in Fig. 12, the path diagram illustrates the direct and indirect effects between design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance, with coefficients quantifying relationship strengths.This analysis provides crucial insights into how design characteristics influence overall recycling performance, both directly and through their impact on recycling process efficiency. It allows for a nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between these factors in LIB recycling systems.

Multi-group analysis: comparison of different battery types

Multi-group analysis in the context of lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency allows for the comparison of structural equation models across different battery types, such as traditional, cell-to-pack (CTP), and cell-to-body (CTB) designs. This approach examines whether the relationships between design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance vary significantly across these battery types.

The multi-group SEM can be represented as:

Where g denotes the group (battery type), \({\Sigma _g}\) is the model-implied covariance matrix, \({\Lambda _g}\) is the factor loading matrix, \({\Gamma _g}\) is the matrix of regression coefficients for exogenous variables, \({B_g}\) is the matrix of regression coefficients for endogenous variables, \({\Phi _g}\) is the covariance matrix of exogenous variables, and \({\Theta _g}\) is the covariance matrix of residuals.

To test for invariance across groups, we use a series of nested models:

-

1.

Configural invariance: \({\Lambda _g} \ne {\Lambda _{g^{\prime}}},{\Gamma _g} \ne {\Gamma _{g^{\prime}}},{B_g} \ne {B_{g^{\prime}}}\)

-

2.

Metric invariance: \({\Lambda _g}={\Lambda _{g^{\prime}}},{\Gamma _g} \ne {\Gamma _{g^{\prime}}},{B_g} \ne {B_{g^{\prime}}}\)

-

3.

Scalar invariance: \({\Lambda _g}={\Lambda _{g^{\prime}}},{\Gamma _g}={\Gamma _{g^{\prime}}},{B_g} \ne {B_{g^{\prime}}}\)

-

4.

Strict invariance: \({\Lambda _g}={\Lambda _{g^{\prime}}},{\Gamma _g}={\Gamma _{g^{\prime}}},{B_g}={B_{g^{\prime}}}\)

The chi-square difference test is used to compare these nested models:

with degrees of freedom:

Table 15 presents the results of the multi-group invariance testing for different battery types. This table provides a comprehensive overview of the model fit indices and chi-square difference tests for each level of invariance tested.

As shown in Fig. 13, the comparative chart displays path coefficients across different battery types, illustrating variations in relationships between key variables for traditional, CTP, and CTB designs. This multi-group analysis provides valuable insights into how the relationships between design characteristics, recycling process efficiency, and overall recycling performance may vary across different LIB designs, informing targeted strategies for improving recycling efficiency in diverse battery technologies.

Case study: power batteries for new energy vehicles

Comparison of traditional design vs. optimized design

The comparison between traditional and optimized designs of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) reveals significant differences in their recyclability and overall performance. Traditional LIB designs, while effective for energy storage, often present challenges in the recycling process due to their complex structures and diverse material compositions. In contrast, optimized designs incorporate recyclability considerations from the outset, leading to improved end-of-life management.

A key distinction lies in the structural complexity of the batteries. Traditional designs typically feature tightly integrated components, making disassembly labor-intensive and time-consuming. Optimized designs, however, adopt a more modular approach, facilitating easier separation of components and materials during the recycling process. This structural difference is reflected in the Structural Complexity Index (SCI), with optimized designs showing lower values, indicating better recyclability. Material selection also plays a crucial role in the differentiation. While traditional designs often prioritize performance over recyclability, leading to the use of complex composite materials, optimized designs favor more easily recyclable materials without significantly compromising performance. This shift is evident in the Material Diversity Index (MDI), where optimized designs demonstrate a lower score, signifying a more homogeneous and recyclable material composition.

The impact of these design differences extends to the recycling process efficiency and overall environmental footprint. Optimized designs generally require less energy for disassembly and material recovery, resulting in a lower Environmental Impact Score (EIS). Additionally, the economic viability of recycling is enhanced for optimized designs, as reflected in a higher Economic Efficiency Index (EEI).

The impact of these design differences extends to the recycling process efficiency and overall environmental footprint. As presented in Table 16, The quantitative comparison reveals significant improvements in the optimized design across multiple metrics. The structural complexity index shows a 27.1% reduction (from 0.85 to 0.62), indicating substantially simplified battery architecture. Material recovery rates increased by 18.1% (from 72 to 85%), while energy consumption in recycling decreased by 27.1% (from 850 to 620 kWh/ton). Most notably, the economic efficiency index improved by 20.6% (from 0.68 to 0.82), demonstrating the financial benefits of optimized design.

This comparative analysis underscores the importance of integrating recyclability considerations into the initial design phase of LIBs. While optimized designs may require additional upfront investment in research and development, they offer substantial benefits in terms of recyclability, environmental impact, and long-term economic viability.

Life cycle cost analysis

Life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) provides a comprehensive assessment of the economic implications throughout the battery’s lifespan, from production to end-of-life management. This analysis is crucial for comparing traditional and optimized designs, considering both upfront costs and long-term economic benefits.

All costs are normalized to USD per kilowatt-hour (USD/kWh) of battery capacity to facilitate direct comparison between different battery designs and sizes. This standardized unit is widely used in the energy storage industry and allows for meaningful comparison with other studies in the field.

The total life cycle cost (LCC) can be expressed as:

Where \({C_p}\) is the production cost (USD/kWh), \({C_o}\) is the operational cost (USD/kWh), \({C_m}\) is the maintenance cost (USD/kWh), \({C_r}\) is the recycling cost (USD/kWh), and \({V_r}\) is the residual value of recovered materials (USD/kWh).

To account for the time value of money, we use the Net Present Value (NPV) approach:

Where \({C_t}\) is the cost at time t, r is the discount rate, and T is the total lifespan of the battery. The Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) provides a standardized metric for comparison:

Where \({E_t}\) is the energy output in year t.

In this equation, t begins at 0 to properly account for initial capital costs (including production and installation costs) that occur at the start of the battery’s life cycle. Setting t = 0 for the first year ensures that these upfront costs are not unnecessarily discounted, which would occur if t started at 1. This approach aligns with standard practice in energy storage economic analysis, where initial investment occurs at the beginning of the project (t = 0), followed by operational years (t = 1, 2, …, T). The time value of money is then appropriately applied to subsequent cash flows and energy outputs in following years, providing a more accurate representation of the battery’s economic performance over its lifetime.

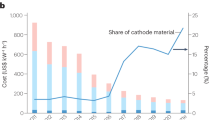

As shown in Fig. 14, the stacked bar chart compares life cycle costs across different LIB designs, breaking down expenses for production, operation, maintenance, and recycling stages. The LCCA reveals that while optimized designs may have higher initial production costs, they often result in lower overall life cycle costs due to reduced operational and recycling expenses, as well as increased value recovery. This is evident in the following comparative table.

The culmination of these factors is reflected in the total life cycle cost presented in Table 17. The comparative analysis demonstrates that while optimized designs incur 20% higher production costs (120 vs. 100 USD/kWh), they achieve cost reductions in all other lifecycle phases: operational costs decrease by 10% (45 vs. 50 USD/kWh), maintenance costs by 16.7% (25 vs. 30 USD/kWh), and recycling costs by 25% (30 vs. 40 USD/kWh). Moreover, the material recovery value increases by 75% (-35 vs. -20 USD/kWh), resulting in a net lifecycle cost reduction of 7.5% (185 vs. 200 USD/kWh).

This analysis demonstrates that optimized LIB designs, despite higher upfront costs, can offer significant economic advantages over their lifecycle, particularly in terms of reduced operational costs and improved material recovery value at the end-of-life stage.

Environmental impact assessment

Environmental impact assessment of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is crucial for understanding the ecological implications of different battery designs throughout their lifecycle15,16. Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of comprehensive environmental assessment approaches17. This assessment typically employs Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology, quantifying impacts across various environmental categories. The overall environmental impact score (EIS) can be calculated using a weighted sum approach:

Where \({w_i}\) is the weight of impact category i, \({I_i}\) is the impact score for category i, and \({I_{i,min}}\) and \({I_{i,max}}\) are the minimum and maximum impact scores across all assessed designs. The Global Warming Potential (GWP), a key impact category, is often calculated as:

Where \({E_j}\) is the emission of greenhouse gas j, and \(GW{P_{100,j}}\) is its 100-year global warming potential. To compare the environmental performance of traditional and optimized LIB designs, consider the following data visualization:

As shown in Fig. 15, the radar chart illustrates the environmental impact comparison across key categories for different LIB designs, highlighting relative performance in areas like GWP and resource depletion.

Resource Depletion, another critical environmental factor, shows a substantial improvement in optimized designs. According to Table 18, the score for optimized designs is 65 kg Sb eq, compared to 85 kg Sb eq for traditional designs, marking a 23.5% reduction. This improvement suggests that optimized designs are more efficient in their use of scarce resources. The environmental impact assessment reveals consistent improvements across all categories. Global warming potential decreased by 20% (from 100 to 80 kg CO2 eq), representing the most significant absolute reduction. Resource depletion showed the highest relative improvement at 23.5% (from 85 to 65 kg Sb eq), followed by toxicity reduction at 21.4% (from 70 to 55 CTUh). Water usage and energy consumption demonstrated more moderate improvements at 16.7% each (60 to 50 m³ and 90 to 75 MJ respectively).

This environmental impact assessment demonstrates that optimized LIB designs generally outperform traditional designs across various ecological indicators. The most significant improvements are observed in resource depletion and toxicity categories, likely due to more efficient material use and selection of less harmful components. These findings underscore the importance of integrating environmental considerations into battery design and highlight the potential for technological innovations to mitigate the ecological footprint of energy storage solutions.

Assessment of recovery efficiency improvement potential

The assessment of recycling efficiency improvement potential for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is crucial for advancing sustainable energy storage solutions. This evaluation encompasses technical, economic, and environmental aspects of the recycling process. The overall recycling efficiency (ORE) can be expressed as:

Where \({w_i}\) is the economic weight of material i, \({m_i}\) is the mass of material i in the battery, and \({p_i}\) is the recovery rate of material i. The improvement potential (IP) for each material can be calculated as:

Where \({p_{i,max}}\) is the theoretical maximum recovery rate for material i, and \({p_{i,current}}\) is the current recovery rate. The total improvement potential is the sum of individual material potentials:

As shown in Fig. 16, the bar graph displays recycling efficiency improvement potential for various materials in LIBs, indicating current recovery rates and maximum achievable rates.

Table 19 offers a breakdown of the current recovery rates, maximum achievable recovery rates, economic weights, and improvement potentials for six critical materials used in LIBs. The data in Table 19 reveals significant variations in recycling efficiency and improvement potential across these materials. Analysis of the recovery efficiency data reveals varying improvement potentials across different materials. Lithium shows the highest absolute improvement potential of 0.15 (from 0.80 to 0.95), followed by cobalt and manganese at 0.10 each. Despite having the highest current recovery rate (0.95), copper shows limited improvement potential (0.02), suggesting that current recovery technologies for copper are approaching theoretical maximums. When weighted by economic importance, lithium (weight: 1.0) and cobalt (weight: 0.8) emerge as priority materials for recovery process optimization.

This analysis reveals significant potential for improving recycling efficiency across various materials in LIBs. Lithium and cobalt show the highest improvement potential, likely due to their high economic value and current technological limitations in recovery processes. The assessment underscores the importance of focusing research and development efforts on these high-potential materials to enhance overall recycling efficiency and economic viability of LIB recycling operations.

Results and discussions

Main research findings

The comprehensive analysis of lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling efficiency has yielded several significant findings.

Firstly, the structural equation modeling (SEM) results reveal a strong positive relationship between optimized battery design characteristics and overall recycling performance, mediated by recycling process efficiency. The standardized path coefficient from design characteristics to recycling process efficiency (γ11 = 0.68, p < 0.001) and from recycling process efficiency to overall recycling performance (β21 = 0.72, p < 0.001) underscore the critical role of design in facilitating efficient recycling processes.

Secondly, the multi-group analysis comparing traditional, cell-to-pack (CTP), and cell-to-body (CTB) designs demonstrates significant variations in recycling efficiency across battery types. CTP and CTB designs show higher recycling process efficiency (RPECTP = 0.75, RPECTB = 0.79) compared to traditional designs (RPETraditional = 0.62), primarily due to their simplified structures and improved material separability.

Thirdly, the life cycle cost analysis reveals that while optimized designs may have higher initial production costs (Coptimized = 120/kWh vs. Ctraditional = 100/kWh), they result in lower total life cycle costs (LCCoptimized = 185/kWh vs. LCCtraditional = 200/kWh) due to reduced operational and recycling expenses, as well as increased material recovery value.

Lastly, the environmental impact assessment shows that optimized LIB designs consistently outperform traditional designs across various ecological indicators, with the most significant improvements observed in resource depletion (23.5% reduction) and toxicity (21.4% reduction) categories. These findings collectively emphasize the interconnectedness of battery design, recycling efficiency, economic viability, and environmental sustainability in the LIB lifecycle.

Theoretical contributions

This research makes several significant theoretical contributions to the field of lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling and sustainable product design. Firstly, it extends the Theory of Design for Recycling (DfR) by providing empirical evidence of the direct and indirect effects of design characteristics on recycling efficiency and overall performance. The structural equation model developed in this study offers a novel framework for quantifying these relationships, bridging the gap between theoretical DfR principles and measurable recycling outcomes.

Secondly, the research contributes to the evolving field of circular economy by demonstrating how product design can significantly influence the closure of material loops in the LIB industry. By integrating life cycle assessment (LCA) with economic analysis, this study provides a more holistic understanding of the circular economy concept, highlighting the synergies and trade-offs between environmental and economic factors in battery recycling.

Thirdly, the multi-group analysis of different battery designs (traditional, CTP, CTB) advances the theoretical understanding of how technological innovations in product architecture can impact end-of-life management. This comparative approach offers insights into the differential effects of design choices on recycling processes, contributing to the broader theory of sustainable innovation in the energy storage sector.

Lastly, the development and application of novel metrics such as the Structural Complexity Index (SCI) and Material Diversity Index (MDI) contribute to the methodological toolkit for assessing product recyclability. These indices provide a quantitative basis for comparing different designs, potentially applicable beyond the LIB industry to other complex product systems.

Practical implications

The findings of this research have several important practical implications for the lithium-ion battery (LIB) industry, policymakers, and recycling operators. Firstly, battery manufacturers should prioritize recyclability in their design processes. The study demonstrates that optimized designs, while potentially more costly upfront, lead to significant economic and environmental benefits over the battery’s lifecycle. Implementing design strategies that reduce structural complexity and material diversity can substantially improve recycling efficiency and reduce end-of-life management costs.

Secondly, recycling operators can use the insights from this study to optimize their processes for different battery types. The multi-group analysis highlights the need for tailored recycling approaches for traditional, CTP, and CTB designs. Investing in flexible recycling technologies that can efficiently handle various battery architectures will be crucial for maximizing material recovery and economic returns.

Thirdly, policymakers should consider incentivizing the adoption of recyclable battery designs. The life cycle cost analysis provides a strong economic argument for such policies. Regulations that require manufacturers to internalize end-of-life costs or meet specific recyclability standards could drive innovation in battery design and recycling technologies.

Lastly, the environmental impact assessment underscores the importance of a holistic approach to sustainability in the LIB industry. Stakeholders should consider not only the performance and cost of batteries during their use phase but also their entire lifecycle environmental footprint. This may involve developing standardized eco-design guidelines for LIBs and incorporating recyclability ratings into product labeling and procurement decisions.

Research limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between lithium-ion battery (LIB) design and recycling efficiency, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the research primarily focused on current LIB technologies and recycling processes. The rapid pace of innovation in the battery industry means that new designs and materials may emerge, potentially altering the relationships identified in this study. Future research should continuously update the model to account for technological advancements.

Secondly, the data used in this study was collected from a limited number of battery manufacturers and recycling facilities. While efforts were made to ensure representativeness, the findings may not fully capture the diversity of practices across the global LIB industry. Expanding the sample size and geographical scope in future studies could enhance the generalizability of the results.

Thirdly, the life cycle cost analysis and environmental impact assessment relied on several assumptions and simplifications due to data availability constraints. Factors such as regional variations in energy costs, labor rates, and environmental regulations were not fully accounted for. More granular data and region-specific analyses could provide more accurate assessments of economic and environmental impacts.

Lastly, the study focused primarily on the technical and economic aspects of recycling efficiency. Social factors, such as consumer behavior, public perception of recycled materials, and labor conditions in recycling facilities, were not extensively explored. Integrating these social dimensions into future research could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in LIB recycling.