Abstract

Aiming at the problems that the uncertainty modeling process of price-based demand response is oversimplified, inconsistent for change pattern of error, and the reliability in user’s comprehensive satisfaction is neglected in the optimal scheduling for power system under multiple uncertainties, integrated factors of economy, environment and society, a multi-objective robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model considering power demand response and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity under multiple uncertainties is proposed. On the basis of analyzing the operation mechanism of the multi-source system and the characteristics of multiple uncertainty sources, the robust theory is used to construct power output model of wind and photovoltaic (PV), and the fuzzy theory is used to construct power demand response model. Taking the lowest comprehensive operation cost as the economic objective, the smallest emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants as environmental objective and the largest user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity as the social objective, based on the robust fuzzy theory, the multi-objective uncertainty optimal scheduling model is constructed, which is transformed into deterministic model and then solved by intelligent optimization algorithm. Based on the improved IEEE-39 node system to verify the validity and superiority of the price-based demand response uncertainty modelling method and multiple uncertainty modelling method in this paper, as well as the reasonableness and necessity for considering the reliability in the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity and the multiple uncertainties in power system optimal scheduling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vigorously promoting the construction of multi-energy complementary clean energy base is the key carrier and the necessary way to build new type power system1,2. The northwest of the China has abundant wind and solar energy, but less flexibility resources, the overall regulation performance is poor. Take advantage of the energy-shifting and schedulability characteristic of the emerging concentrating solar power(CSP) to establish a wind-photovoltaic-photothermal integrated clean energy base, give full play to the flexible regulation performance of the CSP3, and through the power demand response mechanism, the flexible response enthusiasm of the demand side is mobilized4, thereby reducing the peak-shaving pressure of grid-side thermal power units and improving the renewable energy consumption rate. However, in the process of the integrated operation of clean energy base involving multiple types of power sources with strong random wind power and PV power, the system uncertainty factors bring great challenges to the grid scheduling and safe and stable operation5. In the future, the uncertainty conditions faced by new type power system will be more complex, the uncertainty factors will be more prominent, and the multi-objective conflicts will be more significant and coupled with each other. To this end, this paper develops a study on the participation of wind-photovoltaic-photothermal multi-source complementary power generation system in integrated grid scheduling under multiple uncertainties.

Scholars at home and abroad have carried out a lot of research on optimal scheduling of power system under multiple uncertainties and have achieved certain results6,7,8,9. During the construction of new type power systems, uncertainties such as renewable energy, load, and market environment are becoming more and more prominent, and the modeling accuracy of uncertainty sources is also increased. Load-side power demand response (DR), as one of the uncertainty sources, has been an indispensable component of power system flexibility regulation10, which includes price-based DR and incentive-based DR. For price-based DR modeling, literature11,12 establishes a price-based DR uncertain response model and an interruptible load response model; literature13 analyzes the influencing factors of price-based DR uncertainty and constructs a load fuzzy response model; literature14 constructs a price-based DR uncertainty model and designs an incentive-based DR mechanism that combines rigid constraints and elastic constraints; literature15 analyzes the response uncertainty of various types of flexible loads based on literature14, and establishes their respective corresponding response models; literature16 proposes a load model that comprehensively considers the load self-elasticity coefficient and price-based DR uncertainty; literature17 models the relationship between load transfer rate and electricity price under time-of-use electricity price. The above-mentioned literatures mainly construct a price-based DR uncertainty model based on the principles of consumer psychology through reasonable partition and considering the variation pattern of deviation interval caused by uncertainty. However, the model has the drawbacks of certain simplification and inconsistent for change pattern of error. For the linear region, the DR deviation interval in the literature13,14,16 adopts the pattern of ‘first increasing and then decreasing’, but in the literature15, the DR deviation interval in the linear region gradually increases, and the DR deviation reflects the pattern of ‘first increasing and then decreasing’ in the whole response process. Under the time-of-use electricity price environment, it is known that the DR deviation interval in the linear zone has the pattern of ‘first increasing and then decreasing’ through the prediction deviation change mechanism of price-based demand response. For the dead zone, the deviation of load response rate is zero in literature14 but not in literature15. In practice, the dead zone is affected by non-economic factors and the deviation cannot be zero, and the literature14 is oversimplified. In literature15, the dead zone deviation gradually increases from zero, while literature16 believes that it always remains constant. There is no specific change pattern of DR deviation in the dead zone. For the saturation zone, the deviation interval of load response goes directly to zero through the linear zone in literature14 and literature16, while it is limited by the upper limit of the response capacity and gradually decreases to zero after passing through the linear zone in literature15. In the saturation zone, where economic factors dominate, there is less uncertainty, but as the electricity price difference increases, it should gradually reduce to zero, rather than directly to zero. For incentive-based DR modeling, it is mostly treated as a deterministic quantity due to the fact that it is usually implemented based on the signed contract with a ‘reverse penalty’ characteristic and the response uncertainty is relatively small11,17. However, due to multiple factors such as baseline load forecast, user response execution, reducible load demand, and user emergencies the next-day14, the actual response capacity of incentive-based DR may deviate from the expectation, and its response potential cannot be fully exploited if its uncertainty is not taken into account. In addition, if the uncertainty factors in the system are not fully considered, it will not only affect the economic benefits, but also pose a threat to the safe and stable operation of the system. Safety and stability are always the basic requirements and prerequisites for the normal operation of the power system and reliable power supply.

User’s satisfaction with electricity affects users’ motivation to participate in DR projects. For user satisfaction with electricity, the current research mainly focuses on its index construction methods. The literature18 constructs corresponding electricity satisfaction indexes for the three types of flexible load users by integrating the characteristics of respective attributes and economics. The literature19 considers comfort, economy and priorities, and uses a normalization method to define user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity; The literature20 considers comfort and economy, and defines user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity by simply multiplication of the two; The literature21 considers comfort and economy, and uses an indicator method to define the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. The above literatures mainly focus on defining user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity around the attributes of economy and comfort, and lack the necessary consideration of reliability with electricity. Ensuring the reliability is the basic requirement and prerequisite for users to actively participate in DR projects.

For the analysis of multiple uncertain factors such as randomness and fuzziness in decision-making variables in new power systems, stochastic optimization, fuzzy optimization and robust optimization methods are currently mainly used22,23. However, when only one theory is used to model the dual uncertainty of the source and load, due to the differences in the mechanistic models and prediction accuracy, and the uncertainty of corresponding variables with different characteristics, the models constructed are not uniform and relevant, and the optimization results are not optimal. Moreover, the existing improvement methods have been maturely applied and are not very novel. It is also difficult to improve them in a deeper level. Therefore, the source-load double uncertainty problem cannot be accurately described based on only one theory. In response to this problem, relevant scholars combined the advantages of stochastic optimization, fuzzy optimization and robust optimization methods, adopted different theories, and unified the uncertainty model into a dispatch model to focus on solving the source-load dual uncertainty problem. Literature24 combines the advantages of stochastic optimization and robust optimization and proposes a distributed robust optimization scheduling model. Literature12 uses fuzzy theory and robust theory to construct a robust fuzzy model to solve the source load uncertainty problem. Literature25 proposes a fuzzy stochastic optimal scheduling model for AC-DC hybrid microgrid containing high-density intermittent energy based on fuzzy stochastic optimization theory. At present, the applications of distributed robust optimization and fuzzy stochastic optimization are relatively mature, but there are few studies on fuzzy robust optimization. Moreover, the existing uncertainty set construction methods for robust optimization are still relatively rough and fail to fully reflect the polymorphism of the random distribution of different uncertainty factors. It is difficult to obtain a reasonable and accurate optimal coordination scheme, and there is a large deviation from the actual engineering situation. Based on this, the author further combine and improve fuzzy theory and robust theory on the basis of literature12, referring to the literature26, a new robust fuzzy model is constructed to solve the source-load dual uncertainty problem.

Aiming at the above shortcomings and based on the existing research foundation, this paper first deeply analyzes the uncertainty characteristics of each uncertainty source. On this basis, the robust theory in literature26 is used to model the output uncertainty of wind power and PV power, and fuzzy theory is used to re-model power DR uncertainty. Secondly, a multi-objective uncertainty optimisation scheduling model is established based on robust fuzzy theory by comprehensively considering factors of economic, environment and society. Then, The model is transformed deterministically and solved using an intelligent optimisation algorithm; Finally, the simulation results show that the robust fuzzy dynamic integrated environmental-economic-social optimal scheduling model that considers demand response and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity under multiple uncertainties can balance the system economy, environmental protection and user’s experience, and at the same time effectively improves the system’s ability to withstand risk. The main innovation of the paper: (1) Aiming at the different uncertainty characteristics of multiple uncertainty sources, modeling with their respective appropriate uncertainty theories and establishing an optimal scheduling model based on the improved robust fuzzy theory to reduce the conservatism of the robust optimization results, which improves the optimality of the optimization results to a certain extent and makes the conclusions more accurate; (2) A more objective price-based DR uncertainty response model is reconstructed through in-depth analysis of the price-based DR uncertainty response mechanism, thereby making the load uncertainty model more realistic; (3) Redefine the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity from three perspectives of economy, comfort and reliability, and incorporate it into the optimization goal. The model takes into account the user experience, while the satisfaction index takes into account the user’s electricity reliability, which is closer to the actual scheduling situation of the power grid.

Operation architecture of multi-source complementary power generation system considering multiple uncertainties

Integrating wind farms, PV power plants and CSP plants to build a clean energy complementary power generation base to participate in integrated grid scheduling. Its operation architecture is shown Figure A1 in Appendix23.

Under the goals of carbon peak and carbon neutrality, priority is given to grid-connected generation of wind power and PV power from clean energy bases, and combined with CSP and grid-side thermal power generation peak shaving for power grid, while providing basic reserve capacity. In addition, grid flexibility is enhanced through load-side DR. The electric heating device and solar collector provide heat source for CSP plants, when the base output is higher than the load demand, reduce the total thermal power output on the grid side. The excess wind power and PV power is converted into heat energy through electric heating device and stored in high temperature molten salt tank. When the base output is lower than the load demand, increase the output of the CSP power plant through the electric heating device and high temperature molten salt tank in order to satisfy the source-load power balance. The electric heating device not only reduces the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and atmospheric pollutants as well as the abandonment rate of wind power and PV power, but also increases the heat source for the CSP plant, thereby improving the system’s upper and lower flexibility regulation ability and operating economy. By analyzing the uncertainty characteristics of multiple uncertainty sources and considering the factors of economic, environment and society, a multi-objective optimal scheduling model is constructed based on the robust fuzzy theory, so as to maximize the benefits of each target subject while satisfying the safe and reliable operation of the clean energy base, and ultimately achieve the goal of relative optimum of the environmental, economic and social benefits of the system.

Modelling of multiple uncertainties

The uncertainty sources of the multi-source system in this paper mainly consider the uncertainty of output of wind and PV and system load. Focus on analyzing and studying the DR uncertainty mechanism, and reestablish the DR uncertainty model based on existing research to obtain the uncertainty model of the system load.

Uncertainty output model of wind power and PV power

Affected by various factors such as wind speed, illumination intensity, weather conditions, and geographical location, the prediction accuracy of wind power and PV output in actual operation is low and has strong volatility and uncertainty. In addition, the wind power and PV power output are constraints, and its uncertainty affects the safety and economy of system operation. In order to ensure the reasonableness of the scheduling results under extreme cases, the robust theory is used to model the wind power and PV output. Referring to22, considering the difference in random distribution characteristics of uncertainty factors about wind power and photovoltaic power, based on the chance constraints of classification probability, a classified adjustable uncertainty set of the output of wind power and photovoltaic power is constructed to achieve an accurate description of the robustness about the optimal dispatch plan while reducing the conservatism of robust optimization results.

(1) Uncertainty output set of wind power

where, \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}\) is the wind power output at time t, \(\overline{P}_{{{\text{wp}},t}}\) is the predicted wind power output at time t, \(1 - \varepsilon_{t}\) is the confidence level of wind power output in period t, and \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{\text{l}}}\) and \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{\text{u}}}\) are the upper and lower limits of the confidence interval of wind power output.

(2) Uncertainty output set of PV power

where, \(P_{{{\text{pv}},t}}\) is the PV output at time t, \(\overline{P}_{{{\text{pv}},t}}\) is the predicted PV output at time t, \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{\text{l}}}\) and \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{\text{u}}}\) respectively represent the upper and lower limits of the confidence interval of the PV output at the confidence level \(1 - \varepsilon_{t}\).

Load modelling considering power demand response uncertainty

DR is an important means for the demand side to participate in the flexible interaction of the power grid. It plays an important role in guiding users to use electricity rationally, improving the level of renewable energy consumption and grid operation flexibility, and reducing power system operation cost and peak-valley differences10. DR behavior has made the system load a relatively controllable resource. According to the response mechanism, it can be divided into price-based DR and incentive-based DR. In this paper, price-based DR is for transferable loads and incentive-based DR is for shiftable loads and class A and B curtailable loads. Existing studies show that the actual DR scheduling effect is affected by multiple factors such as the number of users, user willingness, user satisfaction, etc. There is a large uncertainty in the user load reduction capacity, transfer rate, etc. Therefore, analyzing its uncertainty can make the scheduling plan more comprehensive and more fully exploit its scheduling potential. However, there is a lack of historical data on DR uncertainty, and the probability distributions in different regions vary greatly, making it difficult to accurately establish its probability distribution function. Fuzzy numbers can be used to obtain the membership function of uncertain parameters by an expert system in case of incomplete information. Therefore, this paper uses fuzzy theory to establish a DR response model and design an incentive DR response mechanism, while laying the foundation for research on integrated scheduling of power generation and consumption in the power grid.

Uncertainty model of price-based DR

Under time-of-use electricity price environment, the electricity price difference and load self-elasticity coefficient mainly affect load response rate16. Define the load self-elasticity coefficient as shown in Eq. (3).

where, \(\lambda_{\Delta q,t}\) is the load response rate in t period, characterising the user response level. For the transferable load, it is the load transfer rate, and for the curtailable load, it is the load reduction rate. \(\lambda_{\Delta c,t}\) is the electricity price change rate in t period, and \(\varepsilon_{tt}\) is the load self-elasticity coefficient in t period.

When price-based DR uncertainty is ignored, the predicted value of load response is shown in Eq. (4).

where, \(\Delta p_{{{\text{f}},t}}\) is the prediction value of price-based DR response in period t, \(\Delta t\) is a period of time in the scheduling cycle, and \(p_{{{\text{fL}},t}}\) is the load prediction value in period t.

Considering the uncertainty of price-based DR, under the time-of-use electricity price environment, based on the principles of consumer psychology, the response model that reflects the relationship between load response rate and electricity price is established through reasonable partitioning and combined with the deviation interval change pattern caused by uncertainty, so as to exact quantitative analysis of load response. With the increase of electricity price difference, the load response situation is divided into dead zone, linear zone and saturation zone. Considering the change pattern of prediction deviation, the load response rate of load in different zones is expressed by segmented linear function. As shown in the literature13, in the linear zone, the maximum prediction of the load response rate shows a trend of ‘first increasing and then decreasing’. On this basis, the change pattern of this response prediction error is applied to the price-based DR modelling in this paper, and a new load actual response model that considers the uncertainty of price-based DR is established by comprehensively considering the load response rate and its prediction error.

Taking the peak and valley load response rate as an example, the relationship between the load response rate and the electricity price difference under peak and valley electricity prices can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 1. The red line represents the load response rate curve, and the blue line represents the maximum prediction error range of the load response rate, that is, the load response rate interval. \(\Delta P_{{{\text{pv}}}}\) is the peak-valley electricity price difference, \(\Delta P_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{\max }\) is its maximum value, \(\lambda_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{\max }\) is the upper limit of peak and valley load response rate; \(\Delta P_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{a}\) and \(\Delta P_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{b}\) respectively represent the peak-to-valley electricity price difference corresponding to the inflection point of the dead zone-linear zone and the inflection point of linear zone-saturation zone. \(\Delta P_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{{{\text{IP}}}}\) is the peak-to-valley electricity price difference corresponding to the inflection point before and after the error value is affected by the electricity price difference in the linear zone, \(\lambda_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{{{\text{IP}}}}\) is the load response rate corresponding to the inflection point. \(d_{{{\text{pv}}}}\) is the maximum prediction deviation, when fuzzy parameters are used to represent load response uncertainty, the value is used as the membership function parameter of the response rate.

When the load response is in the dead zone, the incentive level of electricity price is low, and the uncertainty mainly comes from non-economic factors. Since there is no specific pattern to follow, the response prediction error can be regarded as a constant value. At this time, the load response rate may be negative. Within the linear zone, as the incentive level of electricity price increases, the load response rate increases, the impact of the external environment on the response rate increases, and the prediction error shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. In the saturation zone, the incentive level of electricity price is high enough, and economic factors dominate. Scheduling potential and response fluctuation behaviour are not affected by non-economic factors. As the incentive level of electricity price increases, the response uncertainty decreases due to the profit-driven effect. When the response capacity reaches the upper limit, the uncertainty and prediction error gradually decrease to zero. Based on the above analysis, the hourly loads after the price-based DR response are simulated by considering the peak-valley, peak-flat and flat-valley load responses.

Referring to the research results of15 and combining it with Fig. 1, the load response rate under peak and valley electricity prices is shown in Eq. (5).

where: \(\tilde{\lambda }_{{{\text{pv}}}}\) is the peak and valley load response rate, which is a fuzzy variable and uses a triangular membership function, \(\varepsilon\) represents the variation coefficient of the load transfer rate with the peak-valley electricity price difference in the linear region.

It can be seen from Fig. 1 that the maximum deviation of the peak and valley load response rate changes with the electricity price difference as shown in Fig. 2, specifically as shown in Eq. (6).

where, k1 and k2 respectively represent the change coefficient of the maximum deviation of load response rate with the electricity price difference before and after the inflection point electricity price difference.

Equations (5) and (6) are the peak and valley load fuzzy response model. Similarly, the load response rates \(\overline{\lambda }_{{{\text{pf}}}}\) and \(\overline{\lambda }_{{{\text{fv}}}}\) during the peak-flat and flat-valley periods under the same working conditions can be obtained. By substituting \(\overline{\lambda }_{{{\text{pv}}}}\), \(\overline{\lambda }_{{{\text{pf}}}}\) and \(\overline{\lambda }_{{{\text{fv}}}}\) into the period fitting load expression of the above price-based DR response model, the period fitting load under price-based DR can be obtained, as shown in Eq. (7).

where, \(\tilde{P}_{{{\text{L}},t}}\) is the day-ahead fitting load, Pp-av and Pf-av represent the original load average values during peak and flat periods respectively, and Tp, Tf and Tv are the set of peak, flat and valley periods.

Combining Eqs. (4), (5), (6), and (7), the load response considering price-based DR uncertainty can be obtained, as shown in Eq. (8).

where, \(\Delta \tilde{p}_{{{\text{un}},t}}\) is also a fuzzy variable, there is \(\Delta \tilde{p}_{{{\text{un}},t}} = (\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}1,t}} ,\;\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}2,t}} ,\;\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}3,t}} )\). Among them, \(\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}1,t}} ,\;\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}2,t}} ,\;\Delta p_{{{\text{un}}3,t}}\) represent the parameters of the trigonometric membership function.

The price-based DR response is the sum of the deterministic value of the predicted value of the load response and the load response under the uncertainty of the price-based DR, as shown in Eq. (9).

where, \(P_{t}^{{{\text{DR}}}}\) is the price-based DR response in period t, which is a fuzzy variable.

According to the equation for calculating the expected value of the triangular fuzzy function28, \(P_{t}^{{{\text{DR}}}}\) is converted into a deterministic expression as shown in Eqs. (10) and (11).

Uncertainty model of incentive-based DR

This paper signs a contract management mechanism for Class A curtailable loads (signing contracts with load aggregators), Class B curtailable loads (using direct load control), and shiftable loads. The specific response mechanisms refer to14. Fuzzy parameters are used to express its actual response capacity, taking Class B reducible load as an example, as shown in Eq. (12).

where, \(\Delta \tilde{P}_{{{\text{XJ,}}j,k}}^{{\text{B}}}\) and \(\Delta P_{{{\text{XJ,}}j,k}}^{{\text{B}}}\) represent actual response capacity and planned response capacity of Class B reducible load respectively, rk1 and rk3 are deviation coefficients.

\(\Delta P_{{{\text{XJ,}}j,k}}^{{\text{B}}}\) should satisfy the response capacity upper limit constraint stipulated in the contract, as shown in Eq. (13).

where, \(\Delta P_{{{\text{IL,}}j,k}}^{{\text{B,max}}}\) is the upper limit of the kth class B curtailable load capacity for user j.

The actual incentive response capacity of user j can be expressed as the sum of the actual response capacity of the shiftable loads and the curtailable loads of classes A and B, as shown in Eq. (14).

where, the first item is the actual response of the translatable loads, the second and third represent the actual response of the curtailable loads of classes A and B respectively, NA is the number of class A curtailable loads, \(M_{i}^{A}\) and KB represent the number of bins of the m-th class A curtailable loads i and the k-th class B curtailable loads.

Uncertainty model of system load

The system load uncertainty model can be obtained by combining Eqs. (7) and (14), as shown in Eq. (15):

where, \(\tilde{P}_{s,t}\) is the system period fitting load in period t, which is also a fuzzy variable.

Multi-objective robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model considering demand response and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity

Objective function

This paper constructs a multi-objective robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model with the comprehensive operation cost as the economic goal, emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants as the environmental goal, and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity as the social goal.

System comprehensive operation cost

The comprehensive operation cost includes the operation cost of conventional thermal power units and CSP plants, penalty cost of wind power and PV power abandonment, penalty cost of load shedding, power DR scheduling cost, peaking capacity cost, system additional reserve capacity cost and thermal power unit carbon emissions cost, as shown in Eq. (16).

(1) The operation cost of conventional thermal power units and CSP plants F1.

where, f1 is total operation cost of thermal power unit, including coal combustion cost, startup and shutdown cost, ramp-up cost and environmental protection cost; f2 is total operation cost of CSP plant. The specific expressions are as follows:

where, f1RM is coal combustion cost, f1QT is startup and shutdown cost, f1PP is ramp-up cost; f1HB is environmental protection cost. ai, bi, ci are the fuel cost coefficient of unit i; PG,i,t is scheduling output of unit i in period t. Ui,t is operation status variable of unit i in period t, 1 represents running, 0 represents shutdown. SG,i is the startup and shutdown cost of the i-th unit; T is the total scheduling period; \(\delta_{i}\) is ramp-up cost factor of the i-th unit. \(c_{{{\text{EPC}},i,t}}^{x}\) is unit environmental protection cost of atmospheric pollutants x emitted by thermal power unit i in period t. \(N_{i.t}^{x}\) is mass of atmospheric pollutant x emitted by thermal power unit i in period t. \(\mu_{{{\text{ev}}}}^{x}\) is pollution equivalent value of atmospheric pollutant x. x = 1, 2, and 3 represent SO2, NOx and TSP respectively.

where, Ue,t is operation status variable of the CSP plant in t period, 1 represents operation, 0 represents shutdown; ks is operation and maintenance cost coefficient of the CSP plant; PCSP,t is scheduling output of CSP plant in period t. Se is startup and shutdown cost.

(2) Penalty cost of abandonment power and load shedding F2

where, \(k_{{{\text{wp}}}}^{{{\text{curt}}}}\) and \(k_{{{\text{pv}}}}^{{{\text{curt}}}}\) are power abandonment penalty cost coefficient of wind power and PV power respectively; \(P_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{C}\) and \(P_{{{\text{pv}},t}}^{C}\) are abandonment amount of wind power and PV power in period t respectively. \(k_{{{\text{load,}}t}}^{{{\text{cut}}}}\) is loss cost coefficient of load shedding, and its value is calculated by referring to26. \(P_{{{\text{load,}}t}}^{{{C}}}\) is load shedding capacity.

(3) Power DR scheduling cost F3

In this paper, price incentives are used for transferable loads, contract incentives are used for shiftable loads and curtailable loads, and power DR scheduling cost are the scheduling cost of shiftable loads and curtailable loads.

where, CPY,t is scheduling cost of the shiftable loads in period t, and CXJ,t is scheduling cost of the curtailable loads in period t.

(4) Peak shaving capacity cost F4

where: kp is peak shaving capacity cost coefficient; PR,t is peak shaving capacity purchased at time t.

(5) Additional reserve capacity cost F5

where, kb is system reserve cost coefficient; \(P_{E,t}\) is the additional reserve capacity at time t in addition to the basic reserve capacity provided by thermal power and CSP.

(6) Carbon emission cost F6

where, ui, vi and wi are the carbon emission characteristic coefficient of thermal power unit i, fc is ladder-type carbon emission cost model29.

Emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants

Taking into account the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants from thermal power units and abandoned wind power and PV power, the specific expression is as follows:

where, e1 and e2 are emissions of atmospheric pollutants and CO2 corresponding to thermal power units and abandonment of wind power and PV power. The specific expression is as follows:

where, \(\alpha_{i}\), \(\beta_{i}\), \(\gamma_{i}\) and \(\varphi_{i}\) respectively represent the basic coefficient of air pollutant emission of thermal power unit i. \(e_{{{\text{SO}}_{{2}} }}\), \(e_{{{\text{NO}}_{x} }}\) , eTSP and \(e_{{{\text{CO}}_{{2}} }}\) represent the emissions of SO2, NOx, TSP, CO2 respectively.

User’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity

Power DR causes the load curve to change the next day. If user’s satisfaction with electricity is not taken into account, the scheduling results may harm users’ interests, thereby failing to achieve the purpose of peak load shaving. Based on this, this paper defines user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity from three attributes: economy, comfort and reliability.

(1) Economy with electricity

The electricity purchasing cost greatly affects user’s enthusiasm for participating in DR. The lower the electricity purchasing cost, the higher the economic efficiency, and enthusiasm of users to participate in DR. After implementing DR measures, users choose to increase electricity consumption during valley price periods and reduce electricity consumption during peak price periods. Referring to20, the difference in electricity purchasing cost of users before and after the implementation of DR is used to measure the economic efficiency, as shown in Eq. (32).

where, Reco is the economic index, \(\lambda_{t}\) is the electricity price in period t, and P0,t and P1,t respectively represent the electricity consumption in period t before and after the implementation of DR.

If Reco > 1, the electricity purchasing cost of users will reduce, and its economics will be better than that before DR; If Reco < 1, the electricity purchasing cost of users will increase, and its economics will not be as good as before DR; If Reco = 1, the electricity purchasing cost of users remains unchanged. Therefore, the larger the Reco value, the better the user’s economy with electricity, and the higher the corresponding user’s satisfaction with electricity.

(2) Comfort with electricity

Before DR is implemented, users have the greatest comfort with electricity according to their own electricity habits. Therefore, before DR is implemented, it is assumed that users are most comfortable with their electricity usage in each period. After DR is implemented, users change their electricity consumption behavior under price incentives or contract incentives, and their comfort level decreases. The load curve when the user is not affected by DR is called the maximum comfort curve. Comfort with electricity is measured by calculating the difference between the maximum comfort curve and the actual electricity load curve (the load curve after implementing DR)21, as shown in Eq. (33).

where, Rcom is the user’s comfort index with electricity. The larger the value, the more satisfied the user is. \(\Delta P_{t}\) is the user’s consumption change with electricity in period t.

(3) Reliability with electricity

User’s reliability with electricity is related to the system load shedding rate and is generally inversely proportional to the system load shedding rate. The user’s reliability with electricity is defined as shown in Eq. (34).

where, Rrel is the user’s reliability with electricity, and the larger the value, the more satisfied the user is; Pload,t is the user’s load shedding power in period t.

(4) User’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity

Comprehensive analysis of the above three index attributes, after normalization processing, the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity is obtained, which combines the economy, comfort and reliability with electricity, as shown in Eq. (35).

where, x, y, and z are the weight coefficients of the three indicators. Considering the reliability of the power system and user’s electricity, x = 0.3, y = 0.3, and z = 0.4.

Constraints

The constraints in the paper include the multi-source system’s own constraints and grid constraints, as follows:

(1) System power balance constraints

The total power generation of the system’s operating units must satisfy the requirements of the system’s total load in real time, which is expressed as follows.

where, the fuzzy variables cause the system power balance constraints to fail to give a definite feasible set. It is expressed using credibility chance measure according to the fuzzy stochastic planning theory, Cr is the credibility measure, which is equivalent to the probability measure in probability theory. Therefore, the credibility chance constraint is adopted, that is, the probability that the constraint is established is not less than a certain confidence level, as shown in Eq. (37).

where, Cr{·} is the confidence expression and α is the confidence level for satisfying the system power balance constraints, which reflects the system’s attitude towards risk.

(2) System spinning reserve constraints

The system needs to provide a certain reserve capacity to cope with multiple uncertainties to ensure reliable power supply and good power quality, which is expressed using credibility opportunity constraints:

where, \(R_{t}^{{{\text{up}}}}\) and \(R_{t}^{{{\text{down}}}}\) respectively represent the system can provide upward ramp capacity and downward ramp capacity in period t; \(r_{t}^{{{\text{up}}}}\) and \(r_{t}^{{{\text{down}}}}\) are the unit upward and downward ramp rate; \(P_{G,CSP,E,t}\) is the system reserve capacity in period t; \(P_{G,CSP,E,t}^{\max }\) and \(P_{G,CSP,E,t}^{\min }\) are the maximum and minimum reserve capacity of the system at time t; \(R_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{{\text{up}}}}\), \(R_{{{\text{pv}},t}}^{{{\text{up}}}}\), and \(R_{s,t}^{{{\text{up}}}}\) respectively represent the positive spinning reserve demand caused by the wind and PV and load forecast error in period t; \(R_{{{\text{wp}},t}}^{{{\text{up}}}}\), \(R_{{{\text{pv}},t}}^{{{\text{up}}}}\), and \(R_{s,t}^{{{\text{up}}}}\) respectively represent the negative spinning reserve demand caused by the wind and PV and load forecast error in period t; β1 and β2 are the confidence levels for satisfying the positive and negative spinning reserve constraints respectively.

(3) Output of wind and PV constraints

When formulating a day-ahead dispatch plan, the grid-connected power of wind power and photovoltaic power cannot exceed its rated value. The expression is as follows:

where, \(P_{{\text{wp,N}}}\) and \(P_{{\text{pv,N}}}\) are the rated output power of wind power and PV power respectively.

(4) Operational constraints of CSP plants and thermal units

Due to space limitations, the relevant constraints of CSP plants and thermal power units can be found in literature30,31.

(5) Transmission capacity constraints of transmission lines

where, Fl is the transmission power limit; \(\pi_{i,l}\) is the transmission power distribution coefficient; \(P_{mD,t}\) is the load node power demand.

(6) DR constraints

Price-based DR constraints include electricity price constraints and demand response quantity balance constraints.

where, \(\Delta t\) is the scheduling time interval. Equation (45) is the load response balance within the entire scheduling cycle.

Due to space limitations, the relevant constraints of incentive-based DR will not be described in detail. See literature15 for details.

Deterministic transformation of robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model

This paper transforms Eqs. (36–39). Equation (36) is transformed an interval-free variable form, and Eqs. (37–39) are transformed into a deterministic equivalence classes based on uncertainty programming theory. The specific mathematical transformation process is shown in Appendix C.

Model solving

The basic particle swarm algorithm (PSO) has poor global search capabilities in the later stage and insufficient algorithm diversity, so it is easy to fall into the local optimal solution. So, a multi-objective particle swarm algorithm based on differential evolution is used to solve the model in this paper27. The differential evolution algorithm has the advantages of maintaining population diversity and strong search ability. Introducing it into the PSO algorithm can enhance the algorithm diversity and search ability; During the particle evolution process, flying too fast will cause the algorithm to converge locally. Introducing a speed control strategy can improve the global search performance of the algorithm. The solution process is shown** Figure A2 in Appendix A. The optimal compromise solution is determined based on the literature32.

Example simulation and analysis

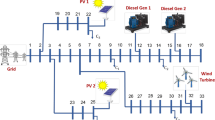

An improved IEEE-39 node system is used to carry out calculation example analysis. The system includes 10 thermal power units, one wind farm, one photovoltaic power station and one CSP station. Among them, the CSP station, photovoltaic power station and wind farm are respectively connected to the 13th, 16th and 18th nodes of the original system. At the same time, the corresponding branch transmission capacity is expanded by 3–4 times to adapt to the grid connection of large-capacity new energy power plants. The system structure is shown in Fig. 3. The rated output power of wind farm and PV power plant are 250 MW and 200 MW respectively. The operation parameters, algorithm parameters and model-related parameters of thermal power units and CSP plants are referenced in27,29. The response parameters of transferable loads to the electricity price incentive level and the contractual content of the curtailable loads are referenced in14,15. The predicted power of wind and PV during the 24 h on a typical day is shown Figure A3 in Appendix A. Peak-flat-valley time-of-use electricity price are used. The time division and corresponding electricity price are shown in Table 1. Confidence level α = β = 0.9. The main parameters of the algorithm: population size 100, maximum number of iterations 1200, c1 and c2 are random numbers in the range of [1.5, 2.0].

Validity analysis of DR uncertainty modeling method

In order to analyze the impact of the DR uncertainty model built in this paper on power grid scheduling results and the necessity of considering multiple uncertainties, the following four scenarios are designed for comparative analysis.

Scenario 1: Only the uncertainty output of wind and PV is considered, and the DR response and system load are both predicted values;

Scenario 2: Considering the uncertainty of wind output and PV output, DR response and system load. In the DR uncertainty modeling process, the DR deviation interval in the dead zone and saturation zone is zero and the DR deviation interval in the linear zone is ‘first increasing and then decreasing’.

Scenario 3: Considering the uncertainty of wind output and PV output, DR response and system load. In the DR uncertainty modeling process, the DR deviation interval in the dead zone and saturation zone is not 0. The dead zone gradually increases and the saturation zone gradually decreases to 0. The DR deviation interval of the whole response process is ‘first increasing and then decreasing’.

Scenario 4: Considering the uncertainty of wind output and PV output, DR response and system load, the method in this paper is used for DR uncertainty modeling.

The total output of wind power, PV power, CSP, and ten thermal power units, peak shaving capacity, wind and PV abandonment, demand response, reserve capacity, original load curve and optimized load curve for each period under four scenarios are shown in Fig. 4. The main indicators of the comprehensive operation cost of the system, emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, total output of thermal power units and its output variance, variance of optimized load, load shedding capacity and wind and PV abandonment under the four scenarios as shown in Table 2.

The scenario 1 does not consider the uncertainty of DR response and system load, and determines the scheduling plan based on its predicted values. As shown in Table 1, the comprehensive operation cost of the system is the lowest in this scenario, but the performance of other indicators is relatively worst. Although the DR mechanism can improve the consumption level of new energy and relieve the pressure of system regulation, if its uncertainty is not taken into account, when the wind and PV and load deviates greatly from the predicted value, it can be seen from Fig. 4a that the system appears to have insufficient flexibility and regulation capacity in the time periods of 07:00–09:00 and 14:00–19:00, which leads to a large number of wind and PV abandonment and load shedding. When the output of wind and PV and load power change drastically, the output variance of CSP and thermal power units increases, and the reserve capacity provided by the system itself decreases. At this time, some thermal power units with poor economy and low efficiency will be turned on, which will lead to an increase in system operation cost and emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant, a decrease in user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. A further decrease in the user satisfaction with electricity while load reduction and transfer under the DR mechanism. Therefore, the comprehensive efficiency of the system in this scenario is low, and the system load shedding is the largest, and the scheduling risk is high, which cannot guarantee the safe and stable operation of the power grid.

The scenarios 2, 3 and 4 all consider the DR response and system load uncertainty, combined with Fig. 4 and Table 2, it can be seen that: the comprehensive operation cost of the system is increased, but the output variance of thermal power unit is improved by 61.18%, 86.21% and 89.44% compared with scenario 1, which is able to cope with the fluctuation of the system uncertainty to a certain extent, and the amount of wind and PV abandonment is reduced by 88.86%, 80.19%, and 97.52% respectively, the new energy consumption rate is improved, the load shedding capacity is reduced by 76.39%, 82.82%, 96.79%, the penalty cost is reduced, and the scheduling process pursues the optimal operation cost. It can be seen from the load shedding capacity that the system will not cause great deviations in extreme working conditions during operation, and has strong anti-risk capabilities. Among them, scenario 4 has the strongest anti-risk ability, followed by scenario 3, and scenario 2 is relatively weak. It also verifies the superiority of the DR uncertainty modeling method in this paper. Overall, after taking into account the increase in uncertainties, although the comprehensive operation cost of the system increases relatively, it can provide an effective decision-making tool for the prevention and control of grid scheduling risks, enhance the effect of source-load interaction, and reduce the risk of grid operation. Thus, it verifies the rationality and necessity of considering multiple uncertainties in the system scheduling and operation process.

In the scenario 2, the output of wind and PV decreases, the total output of thermal power units increases by 913 MW compared with scenario 3, the scheduling pressure increases, and the operation cost increases by 1.76%. Because the output plans of wind and PV are not implemented as planned, the penalty cost increases, resulting in an increase in comprehensive operation cost of the system. At the same time, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant increase, and user’s satisfaction with electricity declines, which reduces the comprehensive benefits of system operation to a certain extent. In the scenario 3, the wind and PV abandonment increases by 79.52 MW compared with scenario 2. It can be seen from the simulation results that the price-based DR modeling method in the scenario 3 can still improve the new energy consumption rate, and can still cooperate with thermal power units and CSP plants, play the role of peak-load shaving, maintain system stability, reduce system operation cost and emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, improve the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. The output of conventional thermal power units decreases, resulting in lower emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, lower carbon emission cost, and lower comprehensive operation cost. Comparing scenario 2 and scenario 3, it can be seen that although the wind and PV abandonment is reduced in scenario 2, it has a greater impact on the comprehensive benefits and security of the system, and the performance of parameter index is worse than that in scenario 3. The main reason is that the DR modelling process that the response deviation of the dead zone and saturation zone is directly 0 in scenario 2, which is oversimplified and the model accuracy decreases. In addition, the randomness of wind power and PV power fluctuates more violently than the fuzziness of DR behavior, and the prediction accuracy is lower than that of DR. Under the same working conditions, the system in scenario 2 needs to configure more reserves to cope with the fluctuations of wind power and PV power, and the pressure on system scheduling decision-making is relatively increased, and the comprehensive benefit is poor.

In the scenario 4, the DR uncertainty modelling method is more rigorous and objective than scenario 2 and scenario 3 in the whole response process, which is more in line with the DR change pattern under the actual operation conditions. Although the comprehensive operation cost is slightly higher than that of scenario 2 and scenario 3, through users orderly load transfer, reduction and translation, the potential of users to participate in power grid scheduling and renewable energy consumption has been deeply explored, and the abandonment rate of wind power and PV power and the risk of load shedding have been reduced. The peak-to-valley difference and volatility of the optimized load curve are significantly reduced, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants are minimized, the absorption of wind power and PV power is maximized, and the risk of load shedding is minimized, thereby ensuring safe and stable operation of the system. Combining Fig. 4 and Table 2, it can be seen that in this scenario, the system has overall good performance in terms of environment, economy, user’s satisfaction with electricity, wind and PV absorption, load shedding, etc. It can better cope with various uncertainties of the system, with good adaptability and obvious environmental, economic and social advantages, thus verifying the effectiveness and superiority of the DR uncertainty modelling method in this paper.

The output of the ten thermal power units under the four scenarios is shown Figure A4 in Appendix A. The output variance of each thermal power unit under each scenario is shown Table B1 in Appendix B. Combined with Figure A4 and Table B1, it can be seen that the overall output of each thermal unit under Scenario 4 is relatively smooth, and the overall variance of the output is also relatively small, thus minimizing the thermal operation cost, as well as improving the operation life of the unit.

Analysis of scheduling results for optimization goals in different dimensions

Based on the model constructed in this paper, the DE-MOPSO algorithm is used to solve the three bi-objective optimisation models of economy-environment, economy-society and environment-society respectively to obtain their corresponding pareto frontiers, and the results are shown in Fig. 5.

As can be seen from Fig. 5a, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant are negatively correlated with the comprehensive operation cost of the system, and the system cannot achieve absolute environmental and economic optimality at the same time. If the goal is to consume renewable energy, the comprehensive operation cost of the system will increase significantly. Figure 5b shows that the comprehensive operation cost of the system is negatively correlated with user’s satisfaction with electricity. This is due to the role of the DR mechanism, which increases the amount of load reduction and transfer, resulting in an increase in DR scheduling cost and system economic cost. As a result, user’s comfort and economy with electricity are reduced, which ultimately leads to a decline in user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. Figure 5c shows that with the increase of emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, the users’ comprehensive satisfaction with electricity decreases, and the two are also negatively correlated. Therefore, in the actual process of optimizing scheduling, it cannot only aim to improve environmental and economic benefits and ignore user’s satisfaction with electricity. It is necessary to comprehensively consider the balance among various optimization goals and achieve the relatively optimal environmental, economic and social benefits through overall coordination and optimization.

Considering the comprehensive operation cost of the system, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, and user satisfaction with electricity, the pareto front is shown in Fig. 6. It can be seen that the pareto front is smooth and the effective solutions are evenly distributed on the pareto front.

Analysis of scheduling results of different user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity

In order to analyze the impact of user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, which takes into account user’s reliability on the basis of economy and comfort, on the optimal scheduling results of the power grid, a comparative analysis of the scheduling results under user’s comprehensive satisfaction with economy-comfort and economy-comfort-reliability is carried out. The comprehensive operation cost of the system, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, the wind and PV abandonment, and load shedding capacity under the two models are shown in Table 3.

It can be seen from the Table 3 that the comprehensive operation cost that considers the reliability with electricity is higher than that without considering the reliability with electricity, but the load shedding and wind and PV abandonment are reduced by 90.74% and 89.49% respectively compared with the former. The user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity is also much higher than the former, and the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants are basically the same. This shows that although the economic benefits are optimized without considering the reliability, it cannot guarantee the new energy consumption and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. The user’s comprehensive satisfaction of with electricity is low, the load shedding capacity is relatively large, and the security of scheduling results needs to be improved. Considering the reliability with electricity, which is the method in this paper, effective interaction between source and load is achieved through the DR mechanism and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, which greatly optimizes wind and PV absorption and load shedding capacity, and improves user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. By taking into account the interests of system economy, environmental protection and user experience, it achieves mutual benefit and win–win among the power grid, user loads and the natural environment, thereby ensuring the safety, stability and reliability of the system and low-carbon economic operation, and also providing a reference for the grid to formulate scheduling plans.

Analysis of multiple uncertainty modeling method

In order to verify the superiority of the robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model constructed in this paper, the following four scenarios are set to compare with the traditional robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model, and the simulation results are shown in Table 4.

Scenario 1: Traditional robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model that only considers the uncertainty output of wind power and PV power.

Scenario 2: This paper’s robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model that only considers the uncertainty output of wind power and PV power.

Scenario 3: Traditional robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model that considers the uncertainty of wind output and PV output and DR.

Scenario 4: This paper’s robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model that considers the uncertainty of wind output and PV output and DR.

As can be seen from the Table 4, for the same model, with the uncertainty factors increase, comparing scenario 1 and scenario 3, scenario 2 and scenario 4, it can be seen that the comprehensive operation cost increases, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants decrease, the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity increases, which is consistent with the conclusion obtained from 5.1. Only considering a single uncertainty factor, comparing scenario 1 and scenario 2, the comprehensive operation cost and emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants of the robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model in this paper are reduced by 6.02% and 1.50% respectively compared with the traditional robust fuzzy optimization scheduling model, user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity increased by 3.76%. Considering multiple uncertain factors, comparing scenario 3 and scenario 4, the comprehensive operation cost and emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant are reduced by 0.99% and 3.81% compared with the traditional model, and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity is increased by 7.35%. The main reason is that the traditional robust optimization model ignores the asymmetry and polymorphism of uncertainty factors, resulting in a large deviation between the assumed distribution and the actual distribution. As a result, the robust optimization results may deviate from the actual results and tend to be conservative. Therefore, the robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model in this paper can effectively alleviate the conservatism of scheduling decisions and obtain superior environmental, economic and social benefits. And when the uncertain factors increase, the model in this paper has a more significant effect on improving environmental, economic and social benefits, has a stronger ability to deal with uncertainty factors, has a larger robust range of feasible solutions, and has better engineering practicality, thereby verifying the feasibility and superiority of the multiple uncertainty modeling method in this paper.

Analysis of the impact of uncertainty parameter fluctuation on scheduling results

In view of the uncertainty factors existing in the system, the fluctuation proportion of ± 2%, ± 4%, ± 6%, ± 8% and ± 10% were set separately for the wind output and PV output and power DR to compare and analyze the impacts of fluctuations of single uncertainty and multiple uncertain factors on the comprehensive operation cost, emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant, and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, The results are shown in Figs. 7 and 8 respectively.

It can be seen from Fig. 7 that when only a single uncertainty is considered, with its fluctuation proportion increases, the comprehensive operation cost, the emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutant, and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity all fluctuate greatly and the fluctuation amplitude gradually increases, and the benefits of environmental, economic, and social scheduling results all decrease. Under the same fluctuation proportion working conditions, the environmental, economic and social benefits of DR are better than those of wind and PV, and the degree of fluctuation of various indicators is relatively small. The main reason is still that the randomness of wind and PV is caused by multifactor, and its ambiguity fluctuates more sharply than that of DR, and its prediction accuracy is lower than that of DR. As can be seen in Fig. 8: When multiple uncertain factors are considered simultaneously, the fluctuations of comprehensive operation cost, emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants, and the user’s satisfaction with electricity are significantly reduced, which shows that the effects of various uncertain factors on system scheduling offset each other, thus reducing their fluctuation amplitude. As the fluctuation proportion increases, the results of environmental, economic and social scheduling remain basically unchanged. In summary, compared with considering a single uncertainty, considering multiple uncertain factors at the same time can reduce the fluctuation range of various scheduling results, and as the fluctuation proportion increases, it can maintain the system’s environmental, economic and social benefits. Therefore, the system that considers multiple uncertain factors at the same time has stronger robustness.

Sensitivity analysis of the model in different confidence levels

The confidence level represents the level of subjective belief in a person. The higher the value, the higher the degree of belief. The power balance opportunity constraints and spinning reserve opportunity constraints are formed with confidence levels α and β. At different confidence levels, the changing trends of comprehensive operation cost, emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity are shown in Fig. 9. The solid line represents α and the dashed line represents β.

As can be seen from Fig. 9, as the confidence level rises, the comprehensive operation cost and pollutant emissions increase, and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity decreases. This is due to the fact that higher confidence levels make the load response rate ambiguity more active, the fluctuation interval increases, and the system has to take on more reserve capacity and peaking capacity, thermal power units with high economic efficiency are burdened with increased peaking and reserve tasks, making it difficult to bear the original output plan. The excess of the plan will be borne by thermal power units with poor economic efficiency, and the cost of coal consumption will increase, which will lead to an increase in the comprehensive operation costs of the system and pollutant emissions, and a decrease in user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. The environmental model, economic model and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity model all have certain sensitivity to the confidence level. From a numerical point of view, the overall change range of confidence level α is more drastic than that of confidence level β. The main reason is that the randomness of wind power and photovoltaic power fluctuates more sharply than the fuzziness of DR. Moreover, the comprehensive operation cost of the system and the amount of pollutant emissions change more than the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, indicating that the comprehensive operation cost of the system and the amount of pollutants emissions are more sensitive to changes in the confidence level than the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity, that is, the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity is more robust than the comprehensive operation costs and pollutant emissions of the system.

Optimization algorithm comparison

Use the basic PSO algorithm, GA-PSO algorithm and DE-PSO algorithm to solve the appendix formula (C.16) respectively, and compare the optimization operation results with the performance index values of the three algorithms. Keep the common parameters of the three algorithms consistent.

The optimization results under the three optimization algorithms are shown in Table 5, the algorithm solution efficiency and satisfaction are shown in Table 6, and the algorithm convergence curve is shown in Fig. 10.

Comprehensive analysis of Tables 5, 6 and Fig. 10 shows that the comprehensive operation cost of system, CO2 and atmospheric pollutant emissions of the system optimized by the PSO algorithm are the largest, the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity is the smallest, and the performance index values of each algorithm are the worst. The main reason is that PSO Algorithms tend to mature prematurely and easily fall into local optima. In contrast, the performance index values of the operation results under the GA-PSO algorithm have been significantly improved. The comprehensive operation cost of system, CO2 and atmospheric pollutant emissions have been reduced by 7.30% and 3.94% respectively, and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity has been increased by 12.69%. The convergence accuracy is better than the PSO algorithm, but it has the largest iteration number and the longest computation time; The DE-PSO algorithm has the best optimization effect, all three indicators are relatively optimal and the convergence accuracy is the highest. The iteration number and calculation time are slightly shorter than the GA-PSO algorithm, which indicates that the DE-PSO algorithm has obvious improvement effect on convergence accuracy, strong global search ability, high computational efficiency, and more reasonable optimization results.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of the uncertainty characteristics of wind power, PV power and power DR response, this paper uses the robust theory to construct the uncertainty output model of wind power and PV power, and uses fuzzy theory to reconstruct the uncertainty model of power DR response. A multi-objective robust fuzzy optimal scheduling model considering DR and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity under multiple uncertainty environments is constructed by comprehensively considering factors of economic, environment and society. The following conclusions are obtained by analyzing the simulation results:

-

(1)

In this paper, the DR uncertainty modelling method and robust fuzzy optimisation model have better effects on smoothing the load curve, reducing the frequent start and stop of conventional thermal power units, easing the pressure of system regulation, and improving the new energy consumption rate. Under the premise of ensuring safe and stable operation of the system, the system environmental and economic benefits and user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity will be greatly improved. The output variance of thermal power units in the scenario is improved by 89.44% compared with scenario 1, which can better cope with the fluctuation of system uncertainties to a certain extent. The Wind and PV abandonment is reduced by 97.52%, and the rate of new energy consumption is increased. The system load loss is reduced by 96.79%, the penalty cost is reduced, and the scheduling process pursued optimal operation costs.

-

(2)

The source addresses the uncertainty of wind power and photovoltaic power based on the robust theory, and the load addresses the uncertainty based on the fuzzy theory, and takes into account the differences in random distribution characteristics of wind power and photovoltaic power, and conducts conservative optimization based on traditional robust scheduling. The built robust fuzzy model achieves optimal compromise dispatch results in three aspects: system economy, environmental protection and users’ comprehensive satisfaction with electricity. Compared with the traditional model, the comprehensive operation cost and CO2 and atmospheric pollutant emissions under this model decreased by 0.99% and 3.81% respectively, and the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity increased by 7.35%, indicating good satisfaction.

-

(3)

In the multi-objective optimal scheduling model that considers factors of economic, environment and society, there is a certain correlation among different objectives. Through the coordination and optimization of each objective, and using the user’s comprehensive satisfaction with electricity that combines economy, comfort and reliability, it can obtain a relatively more reasonable scheduling plan with benefits of economic, environment and society, take into account the interests of various target entities, and provide effective decision-making and operation basis for power grid scheduling.

-

(4)

When taking into account the increase in uncertain factors, although there will be an economic cost, it will also provide guarantee for power grid scheduling risk control, which is conducive to stable operation of the system and reliable power supply to users, making the system more robust. In addition, compared with only considering single uncertainty, considering multiple uncertain factor can reduce the fluctuation range of environmental economic and social scheduling results and maintain the system’s environmental economic and social benefits. Therefore, considering multiple uncertainties is more in line with the actual scheduling situation of the power grid.

This paper has the following flaws that need further improvement:

-

(1)

The calculation model for system emissions of CO2 and atmospheric pollutants only considers the power supply side. In fact, the load side, such as high-energy loads, is also one of its important sources. Subsequent consideration will be given to establishing a unified mathematical model to calculate the emissions on both sides of the source and load.

-

(2)

Electricity price uncertainty is also one of the uncertainty factors that needs to be considered. However, since the price-based DR uncertainty has already been considered, if the electricity price uncertainty is taken into account again, the price-based DR becomes a high-order uncertainty, it belongs to another research point, and we will consider it as a small point to carry out research later.

-

(3)

The simulation example is based on the IEEE-39 node system, and the simulation results are basically consistent with the theoretical derivation. However, due to the conditions, the inability of the power grid dispatching center to provide real data and other reasons, it can not be in accordance with the theory of this paper for the implementation of the field test, the real-world applications are temporarily unavailable. It is expected that the research in this paper will play a guiding role in the regulation and application of actual new power systems in the future.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

National Energy Administration. New power system development blue book (China Electric Power Press, 2023).

Liu, N., Kang, J. & Zhao, C. Development model of multi-energy complementary energy base and comprehensive benefit enhancement method. Proc. CSEE 44(04), 1339–1352 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Source-grid-load multi-time interval optimization scheduling method considering wind-photovoltaic-photothermal combined DC transmission. Proc. CSEE 42(02), 559–573 (2022).

National Development and Reform Commission, National Energy Administration. Guidance on promoting the development of power generation-grid-load-storage integration and multi-energy complementary [EB/OL] (2021-02-25) [2023-01-11]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-03/06/content_5590895.htm

Shen, J. et al. Research Status and prospect of generation scheduling for hydropower-wind-solar energy complementary system. Proc. CSEE 42(11), 3871–3885 (2022).

Lu, Z. et al. Overview on da-ta-driven optimal scheduling methods of power system in uncertain environment. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 44(21), 172–183 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Research review of uncertain optimal scheduling and its application in new-type power systems. High Voltage Eng. 48(09), 3447–3464 (2022).

Lin, S. et al. Research and prospect of the uncertain optimal dispatch methods for renewable energy power systems. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 48(10), 20–41 (2024).

Du, G., Zhao, D. & Liu, X. Research review on optimal scheduling considering wind power uncertainty. Proc. CSEE 43(07), 2608–2627 (2023).

Xu, Z., Sun, H. & Guo, Q. Review and prospect of integrated demand response. Proc. CSEE 38(24), 7194–7205+7446 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. A day-ahead scheduling model considering demand response and its uncertainty. Power Syst. Technol. 38(10), 2708–2714 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Robust fuzzy scheduling of power systems considering bilateral uncertain-ties of generation and demand side. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 42(17), 67–75 (2018).

Luo, C. et al. Influence of demand response uncertainty on day-ahead optimization dis-patching. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 41(05), 22–29 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Multi-time scale decision method for source-load interaction considering demand response uncertainty. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 42(02), 106–113+159 (2018).

Zhao, D. et al. Coordinated scheduling model with multiple time scales considering response uncertainty of flexible load. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 43(22), 21–30 (2019).

Jin, G. et al. Fuzzy random day-ahead optimal dispatch of DC distribution network considering the uncertainty of source-load. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 36(21), 4517–4528 (2021).

Zhao, D. & Yin, J. Fuzzy random chance constrained preemptive goal programming scheduling model considering source-side and load-side uncertainty. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 33(05), 1076–1085 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Demand response trading model of virtual power plant considering electricity consumption satisfaction degree and response quantity expectation. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 43(05), 226–234 (2023).

Guo, X. et al. Multi-attribute demand response strategy of household microgrid based on satisfaction. Acta Energ. Sol. Sin. 42(07), 21–27 (2021).

Tang, W. & Gao, F. Optimal operation of household microgrid day-ahead energy considering user satisfaction. High Voltage Eng. 43(01), 140–148 (2017).

Hou, Y. et al. Research on collaborative and optimization methods of active energy management in community microgrid. Power Syst. Technol. 47(04), 1548–1557 (2023).

Chen, R. Z. et al. Reducing generation uncertainty by integrating CSP with wind power: an adaptive robust optimization-based analysis. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 6(2), 583–594 (2015).

Al-Awami, A. T., Amleh, N. A. & Muqbel, A. M. Optimal demand response bidding and pricing mechanism with fuzzy optimization: application for a virtual power plant. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 53(5), 5051–5061 (2017).

Xia, P. et al. A distributionally robust optimization scheduling model considering higher-order uncertainty of wind power. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 35(1), 189–200 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Fuzzy random optimal operation of hybrid AC/DC microgrid with high density intermittent energy sources. Proc. CSEE 38(10), 2956–2965 (2018).

Peng, C., Liu, B. & Sun, H. Environmental/economic/robust dispatch of power system based on classification uncertainty sets. Proc. CSEE 40(07), 2202–2212+2399 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Robust fuzzy dynamic integrated environmental economic dispatch for multi-source system considering the double uncertainty of source-load. High Voltage Eng. 50(04), 1446–1456 (2024).

Liu, B. Uncertain Planning and Applications (Tsinghua University Press, 2003).

Han, G. et al. Environmental economic dispatch considering emission characteristics of typical industrial loads under demand response. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 47(08), 109–119 (2023).

Jin, H. et al. Multi-day self-scheduling method for combined system of CSP plants and wind power with large-scale thermal energy storage contained. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 40(11), 17–23 (2016).

Li, W. Safe and Economical Operation of Power Systems: Models and Methods 148–149 (Chongqing University Press, 1989).

Liu, G., Zhu, Y. & Jiang, W. Dynamic economic emission dispatch based on hybrid DE-PSO multi-objective algorithm. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 38(8), 1–7 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by Scientific Research Project Supported by China Three Gorges Corporation (62035004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZHANG Hong wrote this article, designed the optimization methods, drew the figures, and performed the simulation as well as the calculus analysis. CHEN Lei and MIN Yong supervised the study, coordinated the investigations, and checked the manuscript’s logical structure. XU Fei validated the simulation and data curation. XI Qianwei and FAN Xiongxiong reviewed the writing and editing. FANG Wenjin and TIAN Nan provided practical suggestions and evaluated the feasibility of the application. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article