Abstract

Zhengzhou city (China) experienced relatively significant land deformation following the July 20, 2021, extreme rainstorm (7·20 event). This study jointly utilised Multi-temporal synthetic aperture radar interferometry (MT-InSAR), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and hydrogeological analysis to quantitatively assess the extent and trends, as well as the causes of land deformation before and after the 7·20 event in Zhengzhou city. The findings detected three major subsidence zones and two uplift zones within the city. The most significant subsidence occurred in the northern part of Zhongmu (− 28 mm/year), the northwest of Xingyang (− 16 mm/year), and the western region of Gongyi (− 6 mm/year). Conversely, a notable uplift was observed in the central city district (13 mm/year) and Xinzheng Airport (12 mm/year). The accuracy assessment of in-situ measurements (GNSS and levelling) yielded an overall root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 2.2 mm/year and an R-square of 0.948. Subsequently, the feature evaluation results based on the XGBoost method suggest that road density and precipitation are the dominant factors affecting land deformation in the entire study area or in the subsidence and uplift zones individually. Nevertheless, the other five factors (groundwater storage, soil type, soil thickness, NDVI, and slope) also act on land deformation individually and are intricately intertwined with each other. Furthermore, hydrogeological analysis from six groundwater wells reveals a synchronous relationship between groundwater level decline and land subsidence. The building load analysis shows a significant correlation between build-up density and subsidence rates, especially for those severe subsidence areas, with the maximum correlation coefficient reaching 0.6312. Finally, the geographic patterns analysis of post-event demonstrated a northeastward trend in land deformation, with a gradual reduction of deformation impact from 2018 to 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land subsidence, the gradual settling or sudden sinking of the Earth’s surface, is often caused by natural phenomena or excessive human intervention, such as groundwater overpumping, urban construction, drought, and flood inundation. This hazard has occurred in more than 150 countries and nearly 1600 major cities1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Among these causes, groundwater extraction and urban development stand out as the most severe drivers of subsidence. For instance, in Pakistan’s Rawalpindi and Islamabad, rapid urban expansion and groundwater overexploitation have destabilised subsurface layers, leading to widespread land subsidence3. Similarly, in Semnan Plain, Iran, groundwater overdraft coupled with broader tectonic conditions has triggered severe subsidence phenomena, affecting both natural landscapes and built infrastructure9. The importance of monitoring land subsidence cannot be overstated, as it provides critical insights necessary for effective land management and urban planning strategies to mitigate these risks10,11. In addition to infrastructure damage, subsidence exacerbates flood risks in urban coastal areas, particularly when combined with the effects of sea-level rise. For instance, in Singapore, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) interferometry has been integrated with sea-level rise scenarios to identify flood-prone areas, demonstrating that local land subsidence significantly amplifies inundation risks7. A similar trend is observed in rapidly urbanising sub-Saharan African coastal cities, where unregulated groundwater extraction and unplanned development disrupt socio-ecological systems, compounding flood vulnerabilities8. Traditionally, precise monitoring of land subsidence has been conducted using methods such as levelling, global navigation satellite system (GNSS) measurements, and laser scanning. These techniques are essential in areas with significant infrastructure, such as high-speed rail networks and airports, where even minor subsidence can lead to substantial economic losses and safety hazards12,13. However, these traditional methods, while accurate, are often limited by high costs and are typically restricted to small geographical areas. Consequently, there is an increasing need for more efficient, scalable, and cost-effective techniques to monitor land deformation at regional and global scales.

With the advent of satellite remote sensing technology, the scope of monitoring has dramatically expanded. Techniques such as Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry (InSAR) have revolutionised the field, enabling the detection of land deformation over extensive areas with unprecedented precision and efficiency with respect to traditional in-situ measurements14,15,16. Globally, InSAR has been successfully applied to monitor subsidence in regions such as Houston, USA, and Mexico City, as well as in agricultural and urbanised areas where groundwater depletion is a critical issue10. These examples highlight the versatility of InSAR for large-scale, high-resolution subsidence monitoring. One of the most widely utilised tools in this field is Sentinel-1 imagery, renowned for its comprehensive spatial coverage, frequent revisit times, and open data access. Its active imaging mode allows all-weather monitoring capabilities, which are crucial for continuous observation, and its relatively short revisits and superior orbit tube control reduce temporal decorrelation errors in dynamic urban environments. Therefore, it has been widely used for research in the fields of landslides, ground settlement, and deformation monitoring of synthetic structures2,11,17,18,19,20,21.

While numerous studies have demonstrated the utility of InSAR techniques in monitoring land subsidence globally, their application in specific urban contexts has provided critical insights into localised deformation patterns and driving mechanisms. In rapidly urbanising regions, such as those in China, subsidence has become a pressing issue due to intensive human activities, including groundwater extraction and urban development. Zhengzhou city, located in central China, serves as a representative case for examining the intricate interplay of natural and anthropogenic factors contributing to land subsidence. Based on Multi-temporal InSAR (MT-InSAR), several studies have leveraged this technology to monitor subsidence in Zhengzhou city and primarily analysed the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of land deformation from a qualitative perspective22,23,24,25. Zhang et al.22 employed persistent scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR) and distributed scatterers InSAR (DS-InSAR) methods to invert the spatial distribution and deformation mean rates of land deformation in Zhengzhou city from 2014 to 2016. The results indicated that most of the subsidence areas were located in the northern and northeastern parts of Zhengzhou city, and the causes attributed to sediment consolidation, water resource development, and urban expansion. Wang et al.23 analysed the patterns of land subsidence in Zhengzhou city jointly using ENVISAT, TerraSAR-X, and Radarsat-2 SAR data from four distinct phases spanning the years 2007 to 2017 for extracting land subsidence information from and levelling campaigns. It concluded that urban expansion was the dominant factor predisposing the evolution of land subsidence. Guo et al.25 processed 364 Sentinel-1 A images based on the Small baseline subset InSAR (SBAS-InSAR) technique to obtain land deformation information in Henan province from 2019 to 2022. The results revealed significant and uneven land subsidence with seasonal variations. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of radar interferometry, particularly MT-InSAR, providing valuable data that supports urban development and decision-making management.

Previous studies and literature have primarily focused on analysing the spatial distribution of MT-InSAR-derived deformation and qualitatively exploring the causes of subsidence while lacking a quantitative assessment of factors driving subsidence rates26. Moreover, there has been limited exploration into the univariate quantitative contributions of land deformation in Zhengzhou city under the combined influence of natural factors (e.g., slope, annual rainfall, soil type, and soil thickness) and human activities (e.g., municipal construction, land use, and groundwater pumping). In particular, there has yet to be a quantitative evaluation of the ground settlement and the factors affecting it before and after the event in Zhengzhou city by combining hydrogeological and building load data.

The utilisation of machine learning techniques, particularly XGBoost and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), has significantly advanced the quantitative assessment of the importance and contribution of various predisposing factors in environmental studies. XGBoost, a highly efficient gradient boosting framework, has been widely praised for its predictive accuracy and performance in complex datasets. SHAP, on the other hand, enhances the interpretability of machine learning models by quantifying the impact of each feature on the prediction outcome, thus offering a transparent method for understanding model behaviour27,28. For instance, Hasan et al.10 employed machine learning to explore the relationships between groundwater stress, aquifer depletion, and land subsidence, achieving high spatial resolution (~ 2 km) in global predictions. These methods have proven effective in identifying key drivers of subsidence and supporting sustainable groundwater management practices in vulnerable regions. These methods have demonstrated considerable advantages in handling non-linear relationships and interactions between variables, particularly in geospatial analysis and model explanation. Consequently, these approaches provide robust technical support for precise evaluations of natural and human activity factors predisposing to city land subsidence.

Therefore, this study obtained a longer SAR observation period from January 2018 to December 2022, focusing on the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of land deformation in Zhengzhou city over an extended period, particularly before and after the 7·20 event. Compared to existing global studies, such as those in Rawalpindi and Islamabad3 and Singapore7, this study provides a detailed analysis of land deformation in Zhengzhou with a unique focus on the post-event period after the 7·20 flood. By incorporating hydrogeological conditions and building load into the analysis, it bridges the gap in quantitative evaluations of subsidence drivers in urban contexts. The external validations were performed using in-situ measurements such as GNSS and levelling campaigns. On this basis, we introduced the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm to construct an initial objective function correlating predisposing factors with the land displacement time series. The XGBoost was employed to ascertain the contribution of each factor to land subsidence quantitatively. In addition, since the fluctuation of the groundwater table and the surface loading both act directly on the overlying soft soil, they are important predisposing factors that contribute to the consolidation and subsidence of the soft soil. Therefore, we delved further into the intrinsic mechanisms of Zhengzhou’s land subsidence from two perspectives: hydrogeological conditions (including Quaternary overburden type and piezometric heads) and building load (reflected by the built-up index). This approach quantitatively analysed the driving factors of land deformation, enhancing our understanding of the dynamic processes underlying land subsidence. Finally, as the geographic pattern analysis can provide a quantitative perspective on the development magnitude and direction of urban land subsidence, we adopted weighted gravity analysis based on standard deviational ellipse to reveal the spatiotemporal evolution trends of land deformation in Zhengzhou city after the 7·20 event. The findings will guide the Zhengzhou city administration to map and properly address potential land subsidence hazards after the 7·20 event.

Study area and datasets

Study area

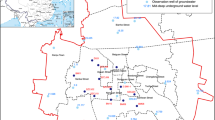

Zhengzhou city (located between 112° 42′ E–114° 14′ E and 34° 16′ N ~ 34° 58′ N), as the capital of Henan province, governs six districts, five county-level cities, and one county, with a total area of 7446 km2. Geomorphologically, Zhengzhou city is characterised by a temperate continental monsoon climate, with an annual average precipitation and annual average temperature of 640.9 mm and 14.4 °C, respectively. It is located in a transitional zone from the western hills to the eastern plain and is bordered to the north by the Yellow River (Fig. 1). The terrain of Zhengzhou generally lies high in the west and low in the east, which is mainly controlled by the north-west tectonic structure; thus, the landscapes on the east and west sides of the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway (Jingguang Railway) are different. On the west side of the track, there are mainly loess hills and hills, with gullies and ravines in the loess plateau area. In contrast, the eastern region comprises the alluvial plains of the Yellow River, exhibiting a vertical discrepancy in elevation exceeding 100 m between these two geographic divisions. The alluvial plain area hosts Quaternary sedimentary deposits, primarily composed of silt, silty clay, fine sand, and medium-coarse sand as predominant lithological constituents29.

Geographical research area. The red rectangle represents the coverage of Sentinel imagery; In-situ observations, including GNSS station, levelling benchmarks, and hydraulic heads of wells, are depicted by solid red triangles, orange cross circles, and yellow-black circles, respectively. The solid black circles are exemplary ground collapse sites, e.g., Longhai Road overpass (a), Xiliuhu Lake subway station (b), Rand Centre carpark (c), and Communications World Mall (d). The background is the TanDEM-X DEM. The inset map shows the location of the study area (light yellow polygon) in Henan province. This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com).

Furthermore, Zhengzhou city is characterised by complex hydrogeological conditions, with a total of 124 rivers, including 29 rivers with large watersheds belonging to the two major water systems of the Yellow River and the Huaihe River. The shallow groundwater is primarily replenished by atmospheric precipitation. The unique geological and hydrological conditions, major demolition and construction over the past decades, and frequent engineering activities have rendered Zhengzhou highly susceptible to wet subsidence loess collapse accidents, as shown in Fig. 1. These were large-scale collapse accidents after long-term soaking in 7·20 event.

Materials and preparation of predisposing factor

This study gathered data across four major categories: satellite imagery, hydrogeological materials, in-situ observational data, and seven potential predisposing factors for land subsidence (see Table 1).

Satellite images: The item mainly contains 51 ascending Sentinel-1 A SAR images and 5 Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) optical multispectral images. The SAR acquisition spans January 2018 to December 2022 and was used to derive the large-scale deformation of Zhengzhou. Given the extensive spatial coverage of the Sentinel-1 A images (250 km wide), this study focused on two adjacent swaths (IW2 and IW3) covering the study area (highlighted by the red rectangle in Fig. 1) for subsidence analysis. The five optical multispectral images correspond to the end of each year and with a cloud cover of less than 1%, i.e., 2018-11-25, 2019-12-30, 2020-12-16, 2021-12-27, and 2022-12-30. These images include five visible and near-infrared (VNIR) bands and two shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands processed to orthorectified surface reflectance. This study used three bands (green, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared 1) to generate the annual built-up density index for 2018 to 2022.

Hydrogeological data: This item contains monthly recorded hydraulic head data from January 2018 to December 2022 for six underground wells (see the yellow-black sphere in Fig. 1) provided by the Henan Provincial Water Resources Department. During the study period, daily precipitation data for Zhengzhou city were downloaded from Visual Crossing (https://www.visualcrossing.com/weather/weather-data-services). Additionally, soil types and thickness data within Zhengzhou city were collected (for details, see “Soil Type and Soil Thickness”). These datasets were utilised to investigate the mechanisms of land deformation from a geotechnical thermodynamics perspective.

In-situ observational data: In-situ measurements for this study contain 13 GNSS stations (see the solid red triangle in Fig. 1) obtained from the Henan Institute of Surveying and Mapping and 22 levelling benchmarks (see the orange cross circle in Fig. 1) were conducted by Henan Provincial Natural Resources Monitoring and Land Rectification Institute. Their annual processed results (North, East, and Up displacement time series for GORS, the elevation variations for levelling) coincide with SAR observation periods and were used to validate the deformation results extracted by the MT-InSAR method.

In addition, seven potential predisposing factors (see Table 1) involve natural factors (slope, soil type, soil thickness and annual rainfall) and human activities (Road density, NDVI, and groundwater storage). The natural breaks method in ArcGIS 10.6 software was used to grade the land deformation results. On this basis, the XGBoost and SHAP methods were used to further investigate the quantitative contributions of the natural and human-activity factors to land subsidence in Zhengzhou city. Each factor is described as follows:

Land deformation rate (Fig. 3): The land deformation rates were determined using the StaMPS-SBAS technique based on Sentinel-1 A SAR data. This panel depicts six ranges of subsidence rates, with values spanning from slight uplift to significant subsidence. These rates highlight the areas most affected by vertical land motion, which are well represented for exploring the quantitative contribution of potentially influential factors to land subsidence.

Slope (Fig. 2a): The slope factor is closely related to the seepage process, shear stress, and gravity effect, which directly affects land subsidence30. TanDEM-X DEM drew the slope map in this study area in the ArcGIS environment, and it ranged from 0° to 62.6°. The panel illustrates the gradient variation across the study area, with steeper slopes delineated in red and flatter areas represented in green.

(a) Topographic slope; (b) Soil type; (c) Soil thickness; (d) Annual precipitation difference (2018–2022); (e) Road density; (f) NDVI difference (2018–2022); (g) groundwater difference (2018–2022). This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com).

Soil type (Fig. 2b): The distribution of 8 soil types across the study area is categorised in this map. Each soil type possesses distinct properties that affect its susceptibility to subsidence31,32,33, such as particle size, cohesion, and drainage capacity. On this basis, we classified Zhengzhou’s soil types into eight categories, empirically assigning values from 1 to 8 to rank their respective influence on land deformation in descending order (Fig. 2c). These classifications were subsequently incorporated into the XGBoost learning model.

Soil thickness (Fig. 2c): Soil thickness influences land deformation, with thicker soils, indicated in green, generally providing better load distribution and water retention, reducing susceptibility to compaction and erosion. Thinner soils, shown in yellow to red, could be more prone to compaction32,34. However, the effect depends on soil type and underlying hydrogeological conditions, making the relationship complex and variable across different landscapes.

Precipitation (Fig. 2d): The variation in annual precipitation captured from 2018 to 2022. Areas with high precipitation differences often experience changes in soil moisture content, impacting deformation behaviour due to hydrological loading and unloading35,36.

Road density (Fig. 2e): The complication of road network is a proxy for human activity and urbanisation level37,38. The road density is shown in Figs. 2e and 6 were derived using the “Line Density” tool in the Spatial Analyst extension of ArcGIS. This method calculates the density of linear features (in this case, roads), providing a spatial representation of road network density across the study area. High road density areas, marked in red, suggest greater anthropogenic loading on the substrate, which can exacerbate land subsidence. Note that only the national highways, provincial roads, railways, county roads, expressways, and level-1 urban arterial roads were selected for road density calculation.

NDVI (Fig. 2f): NDVI serves as an indicator reflecting the relationships among human activities, vegetation changes, and land subsidence39. To ensure consistency in land use/cover data between 2018 and 2022, we selected the maximum NDVI from 16-day interval time series products to represent land use for each year. Subsequently, we computed the differences between the maximum NDVI values across years to capture changes in land use/cover during the study period. Given the threshold characteristics of different scenarios—green vegetation typically ranges from 0.2 to 0.8, built-up areas from 0 to 0.2, and water bodies less than 0—an increase in NDVI suggests enhanced vegetation cover. In contrast, a decrease indicates reduced vegetation or a shift toward built-up land or water bodies. By extracting the differences in the maximum NDVI values of various pixels within the study area, we can better quantify the impact of land use changes on land deformation.

Groundwater storage change (Fig. 2g): Groundwater level changes are often reflected in buoyancy forces on the overlying soil, ultimately characterising the uplift or subsidence of the ground surface26,40,41. Groundwater storage (GWS) was derived by combining the GRACE Mascon solution and the Global Land Data Assimilation System42. The inverted GWS is represented as equivalent water thickness (EWT), which can reflect the groundwater level change in Zhengzhou city during the observation period. Negative values represent a decline in the groundwater level during the study period, which is likely to result in compressive settlement of the overburden and, conversely, a rise in the groundwater level.

Methods

Multitemporal InSAR processing

Zhengzhou city is covered by one track of Sentinel-1 A with a total of 51 images spanning from January 2018 to December 2022 (red rectangle in Fig. 1). Due to the influence of Sentinel-1 A TOPS imaging mode, the registration accuracy of the image azimuth needs to reach 0.001 pixels to avoid interference phase deviation larger than 343. Therefore, based on the principle of minimizing baseline lengths, we initially selected January 3, 2020, as the super master. Then, we performed coarse co-registration before generating interferograms using Sentinel satellite precision orbit. Next, we used an enhanced spectral diversity method based on image information to refine precise co-registration further. Subsequently, taking into account the signal fading issue caused by overly short baselines and the need to improve computational efficiency, we set temporal and spatial baseline thresholds as 120 days and 200 m to maintain the suppression of incoherence caused by long spatiotemporal baselines as much as possible while ensuring that each interferogram has three different connections and does not appear to isolate subsets of interferometric connections. Moreover, the latest TanDEM-X DEM with a spatial resolution of 90 m and an absolute height error of less than 10 m was adopted to remove the topographic phase. Finally, 112 single-look (~ 20 m in azimuth and 5 m in range) differential interferograms were generated. The above processing was performed by GAMMA software44.

Subsequently, the SBAS processing implemented in StaMPS/MTI45 was used to derive the spatial and temporal evolution of land deformation, which mainly include the selection of slowly-decorrelating filtered phase pixels (SDFPs), spatially-uncorrelated look angle (SULA) estimation, and three-dimensional phase unwrapping. However, upon inspecting all interferograms individually, some neighbouring pairs connected to a particular SAR observation were scrutinized to be severely contaminated by long-wavelength phase ramps and short-wavelength turbulence2,18,46. Therefore, we first used linear fitting to estimate the phase ramp from orbital errors and the long-wave atmospheric phase disturbances and then subtracted them from each unwrapped interferogram. Second, the Generic Atmospheric Correction Online Service (GACOS) for InSAR47 was employed to curb the adverse effects of the stratified and turbulent atmospheric phase. Furthermore, various grid sizes were tested for the unwrapping phase derivation, e.g., 200, 100, and 50 m. Poor connections were dropped, and visual inspection procedures were repeated until all interferograms were reliably unwrapped. Finally, displacement time series and mean deformation rates along the line of sight (LOS) were retrieved and converted into vertical deformation by dividing the cosine of the incidence angle.

XGBoost algorithm enhanced by SHAP for feature interpretability

The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm, pioneered by Chen et al.28, is a robust implementation of gradient-boosted decision trees designed for speed and efficiency. This algorithm facilitates the appraisal of variable importance, offering insights into the relative significance of different predictors within the dataset. It enables a comprehensive evaluation of variable importance, providing insights into the relative significance of various predictors within the dataset. Such an approach has garnered attention and application in exploring nonlinear problems under multifactorial influences, marking its emergence in the field48. However, its intrinsic interpretability is limited, particularly in delineating the individual and interactive contributions of predictors to the model’s predictions.

To augment the interpretive utility of the XGBoost algorithm, we incorporate the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method, a sophisticated approach grounded in cooperative game theory to elucidate model outputs from complex machine learning constructs (see supplementary A). The SHAP is adept at disentangling individual feature attributions, providing a granular understanding of feature influence at both the local (single-sample) and global (dataset-level) scales. Our integration of SHAP aims to rectify the interpretability constraints of XGBoost by quantifying the impact of each feature on the predictive outcome. In this study, we adopted the SHAP interpreter to evaluate the above-mentioned seven predisposing factors and MT-InSAR-derived land deformation. For each predicted sample, the model generates a predicted value, and the SHAP value is the numerical value assigned to each predisposing factor in the sample. The SHAP value is calculated as follows27:

where \({x_{ij}}\) represents the \({i_{th}}\) sample of the \({j_{th}}\) predisposing factor; \(f\left( {{x_{ij}}} \right)\) is the SHAP value of \({x_{ij}}\); \({y_{base}}\) signifies the baseline value, which is the mean of all target variables in the dataset; \(\widehat {{{y_1}}}\) is the model’s predicted value. When \(f\left( {{x_{i1}}} \right)>0\), the feature positively influences the predicted outcome, exerting a beneficial effect; inversely, a negative \(f\left( {{x_{i1}}} \right)\) value indicates that the feature reduces the predicted outcome, thereby exerting a detrimental effect.

By integrating the SHAP method with XGBoost, our analysis transcends conventional variable importance metrics, enabling a nuanced exploration of feature contributions that underpin our model’s predictive mechanisms. This synthesis of techniques fosters a comprehensive interpretability method, facilitating informed decision-making and transparent model evaluations.

Extraction of built-up density index

Land subsidence is exacerbated to a certain extent by the increasing building load associated with rapid urbanisation49. Remote sensing-based building indices can quantitatively calculate the proportion and density of built-up areas, thereby indirectly reflecting the surface load exerted by buildings. Normalized difference built-up index (NDBI) is commonly used to extract built-up density50. Although NDBI enhances the identification of built-up areas, its effectiveness varies due to heterogeneity between different urban regions, leading to suboptimal results in some areas during building extraction. Additionally, when using NDBI to enhance built-up areas, it strengthens both built-up areas and bare soil areas. It is found that the reflectance of bare soil and the built-up regions increases from Green to shortwave infrared (SWIR) and then decreases slightly to mid-infrared (MIR). The spectral separation between bare soil and built-up areas usually has higher reflectance, and vegetated water bodies experience a sudden decrease in reflectance in MIR. In this study, the surface reflectance values of three bands from Landsat 8 OLI sensors were used to generate an annual normalized difference red building index (NDRBI)51 for 2018 to 2022 as follows:

where \(NIR\) and \(Green\) are the near-infrared and green bands, corresponding to band 5 and band 3 of Landsat 8 OLI. \(MIR\) is the mid-infrared band; however, due to the absence of a specific wavelength band in Landsat 8 OLI data, we substituted it with the shortwave infrared 1 (SWIR 1) band, which is represented by band 6 of Landsat 8 OLI.

The NDRBI is calculated using Google Earth Engine (GEE), a cloud computing platform developed by Google. Since the Landsat 8 OLI level 2 surface reflectance products have been calibrated and atmospherically corrected in the GEE platform, we can quickly and accurately calculate the vegetation indices for each year. To compare the MT-InSAR-derived subsidence results with NDBI, the MT-InSAR subsidence rates were up-sampled to 30 m to match the Landsat imagery resolution. Finally, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient52 is used to determine the correlation between land subsidence rates and NDRBI results.

Extraction of spatiotemporal evolution characteristic of land deformation

A quantitative expression of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics is indicative of revealing the magnitude, extent, and direction of land deformation53. The standard deviational ellipse (SDE) method calculates the mean centre of geographic elements and measures their standard deviations in various directions around this centre, forming an elliptical graphic. Meanwhile, this elliptical shape reveals the spatial patterns of concentration or dispersion, along with the dominant direction and anisotropy of distribution. Parameters such as the centre, orientation angle, and axis length of the ellipse provide a quantitative description of the centrality, directionality, and trend deviation in the spatial characteristics of geographic elements, which enable a multidimensional analysis and interpretation of geographic phenomena and global spatial distribution characteristics54. Therefore, in this study, we adopted the standard deviation ellipse method, using the current accumulative displacement value, to outline the ellipse shape of SDFPs deformation distribution. This approach can be used to explore the spatiotemporal evolution of land deformation in Zhengzhou city, examining the dual perspectives of “spatial pattern” and “temporal process” from 2018 to 2022. The basic parameters of the standard deviation ellipse, including the ellipse centre, major axis, minor axis, and azimuthal angle, were calculated by Eq. (2) to (3):

where \({x_i}\) and \({y_i}\) are the coordinates of SDFP pixels corresponding to the arithmetic mean centre of \(\bar {X}\) and \(\bar {Y}\), their deviations are \({\tilde {x}_i}\) and \({\tilde {y}_i}\), and n is the total number of pixels in SDFP.

Results

Accuracy and consistency assessment

Figure 3 illustrates the land deformation rates in Zhengzhou city obtained after applying the GACOS correction and converted into vertical direction by dividing the cosine of the look angle. This approach assumes that land deformation primarily occurred in the vertical direction in the North China Plain55. This assumption is further supported by the tiny horizontal movements in the eastward direction (− 1.26 to 1.93 mm/year) observed at 13 GNSS stations compared to the vertical component (see Table S1 in supplementary B). Additionally, transforming deformation results into the vertical direction allows for a more effective causal analysis of groundwater levels. This is attributed to the fact that vertical land subsidence is principally induced by groundwater pumping.

Mean vertical deformation rates in Zhengzhou from January 2018 to December 2022. Positive values (dark blue) represent uplift, and negative values (warm colours) represent subsidence. The red dashed polygons indicate three major subsidence zones: the northern region of Zhongmu (Sub_zone1), the northwest of Xingyang (Sub_zone2), and the western region of Gongyi (Sub_zone3). The black dashed polygons indicate two major uplift zones: the central city district (Upl_zone1) and Xinzheng Airport (Upl_zone2). This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com).

After acquiring deformation rates from StaMPS-SBAS analysis, a meticulous accuracy assessment was undertaken by juxtaposing the derived results with geodetic observations from GNSS and high-precision levelling measurements (Fig. 4). To ensure congruence with the vertical deformation rates retrieved from the StaMPS-SBAS method, the triaxial GNSS displacement vectors (\({d_{North}},{d_{East}},{d_{Upside}}\)) were projected onto the uniaxial radar line of sight (LOS) direction utilizing Eq. (5) and further converted into the vertical direction by simply dividing \(\cos \theta\):

where \({\alpha _s}\) and \(\theta\) are the satellite heading and look angle, respectively.

For the MT-InSAR measurements, we averaged the displacements of all SDFPs within a 300-m area surrounding each GNSS station and levelling point as the final result. Since GNSS processing and levelling campaigns are implemented once a year, it is difficult to compare their only 5-period displacements with the 51 accumulative displacements derived by StaMPS-SBAS. Therefore, we fitted the 5-period displacements from GNSS and levelling to obtain the mean annual deformation rates over the observation period. We compared them with the mean annual deformation rate obtained from StaMPS-SBAS. Figure 4 plots the linear regression between the MT-InSAR-derived mean vertical deformation rates and 33 available in-situ measurements (11 valid GNSS observations and 22 levelling points; see Table S2 in supplementary B). As seen from Fig. 4, among these three types of observations, the rates obtained by StaMPS-SBAS are more consistent with those obtained from levelling measurements, with a standard deviation of 1.7 mm/year. In contrast, for GNSS observation, the standard deviation of the two is 2.8 mm/year, which can be attributed to the lower accuracy of GNSS observation in the vertical direction. The overall standard deviation of both StaMPS-SBAS and in-situ observations is 2.2 mm/year, with a correlation coefficient R-square of 0.948. The discrepancies at all 33 in-situ sites are within twice the standard deviation, i.e., 4.4 mm/year. The linear regression results in Fig. 4 indicate the high accuracy and overall consistency of the derived MT-InSAR results.

Spatiotemporal characteristics of land subsidence

Utilizing the SBAS approach integrated with the StaMPS processing, a high-resolution deformation rate map for Zhengzhou city was successfully generated (Fig. 3) (also see supplementary C). It reveals a total of 479,272 SDFPs, with an average density of approximately 63 SDFPs per square kilometre. Such detailed data significantly enhances the ability to conduct refined investigations into the causes and characteristics of land deformation in Zhengzhou city. As depicted in Fig. 3, aside from significant localized subsidence in the northern region of Zhongmu (Sub_zone1 in Fig. 3), the northwest of Xingyang (Sub_zone2 in Fig. 3), and the western region of Gongyi (Sub_zone3 in Fig. 3), most areas within Zhengzhou city exhibit relative stability. Notably, in Sub_zone1, two unconnected clusters of subsidence are observed, recording maximum subsidence rates of − 28 mm/year and − 21 mm/year, respectively, covering areas of 5.5 km2 and 1.3 km2. In Sub_zone2, despite the maximum and average deformation rates are relatively small, i.e., − 16 mm/year and − 4.9 mm/year, respectively, the land subsidence extends through the southwest and north of Xingyang and covers an area up to 39.9 km2. As for Sub_zone3, the land subsidence clusters are smaller but more concentrated, with an average subsidence rate of -6 mm/year.

In addition, we detected two relatively severe land uplift zones occurring in central Zhengzhou city (Upl_zone1 in Fig. 3) and Xinzheng Airport (Upl_zone2 in Fig. 3). Upl_zone1 is primarily located in the densely populated Jinshui, Zhongyuan, Erqi, and Guancheng districts. Deformation in Upl_zone1 is concentrated and has obvious boundaries, with an area of 59.7 km2 and a maximum uplift rate of 13 mm/year. The Upl_zone2 is located at Xinzheng Airport, where the uplift deformation is concentrated, with a smaller area of 6.3 km2 and a maximum uplift rate of 12 mm/year (Fig. 3).

Figure 5 illustrates the spatial distribution of subsidence and its temporal evolution in Zhengzhou city. Similar to the above analysis, local areas such as Sub_zone1 and Upl_zone1 have undergone significant land deformation. Notably, after the extraordinary rainstorm disaster on July 20, 2021 (7·20 event), the accumulative mean displacement in Sub_zone1 decreased from − 28.2 mm in June 2021 to -32.1 mm in December 2022. The raster units with accumulative subsidence exceeding − 20 mm in this zone also expanded by 86.7% compared to before July 2021. Other deformation zones, such as Sub_zone2 and Upl_zone2, experienced more severe deformation and increased deformation area after the 7·20 event. Overall, the land deformation in Zhengzhou city has shown an escalating trend from January 2018 to December 2022, with a tendency to spread from west to east over time. The number of SDFPs with an absolute deformation displacement (subsidence/uplift) larger than 50 mm increased from 15 raster units in December 2018 to 167 in June 2021 and 779 at the end of 2022 (Fig. 5). Evidently, the land deformation situation in Zhengzhou city sharply deteriorated after the 7·20 event.

Accumulative vertical land displacement was observed between January 2018 and December 2022 by StaMPS-SBAS in Zhengzhou city. The displacement variations are referenced to the Sentinel-1 image from January 1, 2018, with cumulative displacements shown for December 2018, 2019, 2020, June 2021, and December 18, 2022. June 2021 is highlighted in red as the image closest to the 7·20 event. This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com).

Analysis and discussion

Predisposing factors contribute to land uplifting and subsidence zones

The SHAP value distribution depicted in Fig. 6a elucidates the influence of seven factors on the model’s predictive accuracy for land deformation rates. Among these factors, road density and precipitation stand out as the most influential contributors to the model’s predictive accuracy. Road density demonstrates a dominant and consistent positive impact, as its SHAP values span a wide range in both high and low feature values, indicating a strong correlation with areas experiencing higher deformation rates. Precipitation also shows a substantial effect in the overall study area, concentrating on positive areas of SHAP value between 0 and 2. This is closely followed by GWS (high feature value) and soil type (low feature value), showing a moderate influence with compact clusters around the zero SHAP value, suggesting more consistent but less pronounced contributions. The SHAP values of GWS reveal its dual effect: while aquifer depletion intensifies subsidence, recharge contributes to uplift, indicating a complex dynamic between groundwater balance and land deformation. Soil type, meanwhile, consistently impacts deformation, particularly in areas where geological conditions are less stable. In contrast, factors like soil thickness, NDVI, and slope exhibit limited influence, as reflected by SHAP values clustering around zero. While their contributions are less significant, their impacts are not negligible, as they may interact with dominant factors in specific scenarios to drive localized deformation.

The impact of seven potential predisposing factors on land uplifting and subsidence zones in Zhengzhou city was evaluated using SHAP values derived from the XGBoost model. (a) SHAP value distributions for all regions illustrate the contributions of road density, precipitation, GWS, soil type, soil thickness, NDVI, and slope to land deformation predictions. Higher SHAP value dispersion reflects a more substantial impact on land deformation. (b) SHAP values for subsidence zones highlight precipitation as the dominant factor, with road density and soil type showing moderate effects. (c) SHAP values for uplifting zones demonstrate significant influences from precipitation, road density, and GWS, with lower contributions from soil attributes and NDVI. (d) The mean SHAP value impacts each factor, with road density and precipitation emerging as predominant contributors across subsidence and uplift zones. These findings underline the complex interplay between natural and anthropogenic factors affecting land deformation.

The zone-specific analysis further strengthens these findings. In subsidence zones (Fig. 6b), precipitation emerged as the dominant factor with a significant negative impact, as shown by its wide dispersion of SHAP values (− 5 to 3), consistent with the short-term soil expansion caused by precipitation infiltration. Similarly, soil type and soil thickness with low feature value exhibit a moderate negative impact, further reinforcing the influence of geological conditions in these regions. In addition, groundwater storage (GWS) and slope with both high and low feature values had minimal positive impacts, with SHAP values clustered near the origin. Conversely, the uplifted zones (Fig. 6c) exhibit a strikingly different pattern, showing that precipitation, road density, and groundwater storage (GWS) are the primary drivers of land uplift, with precipitation having the most substantial and consistent impact. High precipitation values are strongly correlated with negative land uplift, highlighting the importance of hydrological processes. When precipitation reached a high value, the SHAP value decreased from positive to negative value and concentrated between 0 and − 1. Road density and GWS show a significant positive correlation with SHAP value, indicating the importance of human infrastructure development and groundwater recharge in stabilizing and elevating land surfaces. In contrast, soil type and soil thickness have moderate impacts, reflecting the influence of geological characteristics, while NDVI and slope exhibit minimal effects, suggesting their contributions are secondary. These findings underscore the dominance of hydrological and anthropogenic factors in shaping land uplift and provide valuable insights for urban planning and land management in uplifting regions.

The mean SHAP value analysis, as summarized in Fig. 6d, delineates a clear ranking of the factors’ overall contributions. Road density is identified as the predominant factor across all regions, underscoring the transformative effects of infrastructure development on surface stability. Precipitation ranks second, with its influence particularly pronounced in uplift zones, reaffirming its critical role in vertical land dynamics. While GWS has a variable impact, its significant contribution to both subsidence and uplift highlights its dual role in deformation processes. In contrast, NDVI and soil type show minimal contributions overall, though their roles may still be significant in specific contexts.

According to the above analysis, the interplays between the seven potential predisposing factors that impact land deformation phenomena are intricate. Road density, serving as a surrogate for anthropogenic activity56, correlates with heightened mean impacts on land deformation, most notably in areas with prevalent subsidence. This suggests that human interventions, through infrastructure development, significantly perturb the land surface stability. Precipitation demonstrates a marked influence on uplift zones, aligning with the concept that hydrological variations can lead to land elevation changes. Conversely, GWS has a variable impact on different deformation areas, possibly reflecting the dual effect of aquifer depletion and recharge. While less impactful than road density and precipitation, soil attributes contribute to the subsidence/uplift patterns, hinting at the importance of soil composition and structure in ground movement dynamics. These relationships underscore the complexity of factors governing land deformation and the necessity of multifaceted approaches to land management and urban planning.

Land deformation response to groundwater level changes

Figure 7 illustrates that vertical displacement tends to correlate with groundwater changes inversely: when groundwater levels decrease, subsidence intensifies, and vice versa. This is caused by the geographic location of the study area and factors such as hydrological soils. Located in the Yellow River’s alluvial plain within the North China stratigraphic region, Zhengzhou city is primarily underlain by Cenozoic formations with high porosity and low lithification, rendering the area prone to subsidence. Over the past century, intensive and multi-tiered groundwater extraction has exacerbated this tendency, causing differential subsidence due to the varied thickness of these formations. As groundwater is withdrawn, the resulting decrease in hydrostatic pressure allows the loosely consolidated soil to compact, leading to surface-level subsidence as the soil layers adjust to the new stress regime17,18,49,57.

Time series of vertical displacement derived by StaMPS-SBAS method and groundwater level changes at six wells during the period January 2018 and December 2022 in Zhengzhou city: (1) Huiji_1, (2) Huiji_2, (3) Zhongmu, (4) Erqi, (5) Xinzheng_1, and (6) Xinzheng_2 corresponding to the location (1)–(6) in Fig. 1. The grey bar indicates the daily rainfall schematic diagram, whose length corresponds to the daily precipitation, with a longer bar indicating heavier rain on that day. The red vertical bar represents the moment of the extreme rainstorm event in July 2021. All groundwater level changes in the graph are observed in well data.

To better quantify this relationship, we collected groundwater level data from six groundwater wells (indicated by yellow-black sphere and labelled (1)–(6) in Figs. 1 and 7) uniformly distributed within Zhengzhou city, i.e., numbered as Huiji_1 (1), Huiji_2 (2), Zhongmu (3), Erqi (4), Xinzheng_1 (5), and Xinzheng_2 (6) from north to south. The first three wells are deep groundwater wells with depths reaching 200 m, while the latter two are shallow groundwater wells with depths of approximately 50 m.

Except for observational data loss in Huiji_2(2) observation well at the beginning of the observation period and after December 2021, the other five groundwater wells have completed observational data for five years (January 2018–December 2022). Huiji_1 (1) and Huiji_2 (2), located in Sub_zone2, exhibit a gradual and gentle land subsidence pattern, with accumulative subsidence of − 45 mm and − 38 mm over the five years, corresponding to groundwater level declines of 7.04 m and 5.58 m, respectively. Zhongmu (3) is situated in the most severe subsidence area, Sub_zone1 in Zhengzhou city, with an accumulative subsidence of − 73 mm and a corresponding groundwater level decline of 28.93 m. Moreover, the observation points in these three subsidence zones show a significant and abrupt descent after July 2021 (Fig. 7). Xinzheng_1 (5) and Xinzheng_2 (6), located in the relatively stable southern region of Zhengzhou city, exhibit average displacements of − 5 mm and − 7 mm over the five years, with corresponding groundwater level declines of 0.69 m and 4.87 m. Therefore, comparisons from the five wells indicate a robust overall consistency between groundwater level changes and land deformation, whether in subsiding or relatively stable areas.

To further quantify the correlation between land deformation and groundwater level change, despite the non-strict one-to-one correspondence and different lengths of the two types of observations, we used the bsxfun() function in MATLAB. The bsxfun() function searches for the index of the closest value of the MT-InSAR observation within a specific time window for the well recordings, resulting in equivalent dimensions for the two types of observations (Fig. 7). Then, the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, yielding coherence coefficients of 0.84, 0.81, and 0.85 for the three heavily subsided well locations, i.e., Huiji_1 (1), Huiji_2 (2), and Zhongmu (3). For Xinzheng_1 (5) and Xinzheng_2 (6), where the deformation amplitudes of the two observations are smaller, but the fluctuations are relatively more significant, the Pearson correlation coefficients are 0.61 and 0.52, respectively. Except for the above subsidence and relatively stable areas, the central district of Zhengzhou city exhibits an uplift of approximately 28 mm in the land surface, where the groundwater level at Erqi (4) well has also risen by 4.5 m during the observation period (see the Erqi (4) in Fig. 7). And their Pearson correlation coefficient reaches 0.82. The above results show that groundwater depletion in soft soil areas is the primary driver of land subsidence.

Subsidence related to building load

In the past two decades, Zhengzhou city has experienced unprecedented and rapid urban expansion, extending both outward and upward, with development intensity reaching unprecedented levels. Rapid urbanisation increases building load on the ground surface, potentially leading to additional local land subsidence49. However, the problem of increased building load indirectly caused by urban expansion typically only affects land subsidence and does not lead to ground uplift. Therefore, we focused on extracting areas in Zhengzhou city with land subsidence rates exceeding − 4 mm/year, mainly including the three major subsidence zones (Sub_zone1, Sub_zone2, and Sub_zone3 depicted with a red dashed polygon in Fig. 2), along with some scattered small local clusters (Fig. 8a). This allowed for a quantitative investigation of the relationship between building load and land subsidence.

(a) Area with vertical subsidence rates less than − 5 mm/year, mainly including the Sub_zone1, Sub_zone2, and Sub_zone3. (b) The variations of the NDRBI value from 2018 to 2022 correspond to the area of (a), whose statistical characteristics and density distributions are in (c). This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com) and MATLAB R2022a (https://www.mathworks.com).

Firstly, the vertical deformation rate results of these areas from the StaMPS-SBAS method were up-sampled to the exact resolution as Landsat 8 OLI. Subsequently, following the methods outlined in Sect. 3.3, the NDRBI values were calculated annually from 2018 to 2022, and the inter-annual changes in NDRBI were calculated (Fig. 8b). Finally, the raster results of the two categories of identical resolution units were converted into column vector structures. The average subsidence rate and NDRBI value of each pixel were extracted, and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient method52 was employed to calculate their correlation coefficient (Table 2).

Figure 8b shows that the NDRBI variation values in urbanised areas range from − 0.3 to 0.9 and generally characterise positive values. In contrast, the vegetation-covered areas and waters show negative characteristics and have larger values (Fig. 8c). In Sub_zone1, Sub_zone2, and Sub_zone3, the most rapid sinking rates and the highest NDRBI values are observed. Particularly, in the southwest corner of Sub_zone1, the maximum land subsidence rate reaches − 28 mm/year, covering an area of 4.2 km2. The corresponding maximum NDRBI variation reaches 0.9931, with raster units of variations greater than 0.5 accounting for 1.9 km2.

Furthermore, when the subsidence rates were categorised into three different grades and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients calculated with corresponding NDRBI variations, it was evident that building density exerted a more pronounced impact on areas with higher land subsidence rates. For instance, the correlation coefficient reaches up to 0.6312 within the subsidence rates of − 28 to − 12 mm/year. In regions with moderately severe subsidence rates of − 11 to − 7 mm/year, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients significantly decrease to 0.2641. For those relatively stable areas with subsidence rates from − 6 to − 4 mm/year, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients are 0.0727, which can be neglected (see Table 2). Therefore, the characteristics that large subsidence rates correspond to larger NDRBI variation values and stronger correlation prove the positive contribution of building volume ratio, building density, and the load of high-rise buildings on land subsidence. However, it is essential to note that the contribution is not considered significant.

Analysis of the evolution trend of land deformation in Zhengzhou city

Based on the methodology described in Sect. 3.3, we applied the SDE method, using land subsidence data in Zhengzhou city as input value, to comprehensively depict the spatial pattern and temporal trends of land subsidence from 2018 to 2022 (Fig. 9; Table 3).

Standard deviation ellipses of land subsidence in Zhengzhou city from 2018 to 2022. The ellipses, colour-coded by year, illustrate the shift in subsidence intensity and the movement of the centroid, mainly concentrated in the Erqi district. The zoomed map (right column) traces the year-on-year path of the centroid, depicting a northeastward migration pattern. This figure was generated in ArcGIS 10.6 software (https://www.esri.com).

As shown in Fig. 9; Table 3, the results reveal that the subsidence centroid fluctuated within a small range over the five years, shifting from 113.5543° E, 34.6709° N in 2018 to 113.6229° E, 34.6947° N in 2022, concentrated in the Erqi district. The trajectory of the centroid’s movement experienced a pattern of “northeast (2018 to 2020)-southeast (2020 to 2021)-northeast (2021 to 2022)”, exhibiting an overall oscillatory trend toward the northeast. This movement may be related to urban construction activities, human-induced factors such as groundwater extraction, and potentially linked to the 7·20 event. Apart from the southeastward shift of the centroid in 2021, the orientation angle θ of the standard deviation ellipse gradually increases during the fluctuation process, changing from 77.99° in 2018 to 87.07° in 2022. This indicates that the land subsidence in Zhengzhou city exhibits a spatial distribution pattern characterised by “southwest-northeast.” Additionally, the major axis and area of the subsidence zone show a decreasing trend each year. The major axis reduces from 73.6828 km in 2018 to 58.5903 km in 2022, and the area decreases from 2015.63 km2 in 2018 to 1535.759 km2 in 2022. This reflects a gradual reduction in the extent of the subsidence impact, which may be related to changes in groundwater flow direction or load variations during urban development.

Conclusion

The extensive groundwater pumping over the past decades has triggered land deformation in Zhengzhou city. This situation escalated further after the 7·20 event, as evidenced by our comprehensive five-year study (2018–2022). The number of grids with an absolute MT-InSAR-derived deformation displacement (subsidence/uplift) larger than 50 mm increased from 15 raster units in December 2018 to 167 in June 2021 (only one month prior to 7·20 event) and 779 at the end of 2022. Meanwhile, the mean deformation in three subsidence zones is also reduced, with − 28.2 mm in Sub_zone1 in June 2021 and changed to -32.1 mm in December 2022.

Furthermore, the XGBoost analysis suggests that road density and precipitation are the dominant factors affecting land deformation. In addition, the results of six water wells also showed that land subsidence patterns were consistent with groundwater depletion, with notable variability across different city zones. Three wells in the most subsided areas showed high correlation coefficients (> 0.8) between MT-InSAR-derived subsidence and groundwater level changes, affirming the influence of aquifer depletion on land deformation. In addition, there is a clear correlation between building density and land subsidence rates in Zhengzhou city. Areas with intense urban development show more significant subsidence rates, as evidenced by negative NDRBI values, particularly in heavily built-up zones. The correlation analysis indicates a more robust relationship in regions with greater subsidence rates, confirming that building density significantly influences land subsidence.

Finally, an analysis utilizing the SDE method to assess land subsidence in Zhengzhou city from 2018 to 2022 has uncovered consistent spatial patterns and temporal trends. Over five years, the centroid of subsidence overall indicates a northeastward shift. The SDE’s orientation reflects a distinct “southwest-northeast” subsidence pattern, a diminishing impact of subsidence. This study comprehensively analyses the factors contributing to land subsidence in Zhengzhou city, whose findings can equip policymakers with a clearer understanding of subsidence patterns, enabling the formulation of targeted strategies to mitigate geological risks and preserve urban infrastructure.

Data availability

Datasets used in the section “XGBoost Algorithm Enhanced by SHAP for Feature Interpretability”, displacement time series observed by GNSS sites and levelling campaign, and MT-InSAR derived data are accessible from supplementary materials. The other datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Herrera-García, G. et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 371, 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8549 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. Inferring subsidence characteristics in Wuhan (China) through multitemporal InSAR and hydrogeological analysis. Eng. Geol. 297 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106530 (2022).

Ao, Z. et al. A national-scale assessment of land subsidence in China’s major cities. Science 384, 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl4366 (2024).

Khan, J. A., Ren, X., Hussain, M. A. & Jan, M. Q. Monitoring land subsidence using PS-InSAR technique in Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. Remote Sens. 14, 3722. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153722 (2022).

Tay, C. W. J. et al. Sea-level rise from land subsidence in major coastal cities. Nat. Sustain. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00947-z (2022).

Tzampoglou, P. et al. Selected worldwide cases of land subsidence due to groundwater withdrawal. Water https://doi.org/10.3390/w15061094 (2023).

Catalão, J., Raju, D. & Nico, G. Insar maps of land subsidence and sea level scenarios to quantify the flood inundation risk in coastal cities: the case of Singapore. Remote Sens. 12, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12020296 (2020).

Cian, F., Blasco, J. M. D. & Carrera, L. C. Sentinel-1 for monitoring land subsidence of coastal cities in Africa using PSInSAR: A methodology based on the integration of SNAP and StaMPS. Geosciences. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9030124 (2019).

Mohammady, M., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Amiri, M. Assessment of land subsidence susceptibility in Semnan plain (Iran): a comparison of support vector machine and weights of evidence data mining algorithms. Nat. Hazards. 99, 951–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03785-z (2019).

Hasan, M. F., Smith, R., Vajedian, S., Pommerenke, R. & Majumdar, S. Global land subsidence mapping reveals widespread loss of aquifer storage capacity. Nat. Commun. 14 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41933-z (2023).

Xu, Y., Wu, Z., Zhang, H., Liu, J. & Jing, Z. Land subsidence monitoring and building risk assessment using InSAR and machine learning in a Loess Plateau City—A case study of Lanzhou, China. Remote Sens. 15, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15112851 (2023).

Peyret, F., Bétaille, D. & Hintzy, G. High-precision application of GPS in the field of real-time equipment positioning. Autom. Constr. 9, 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-5805(99)00058-8 (2000).

Philipp, M., Dietz, A., Buchelt, S. & Kuenzer, C. Trends in satellite earth observation for permafrost related analyses—A review. Remote Sens. 13, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13061217 (2021).

Galloway, D. L. et al. Detection of aquifer system compaction and land subsidence using interferometric synthetic aperture radar, Antelope Valley, Mojave Desert, California. Water Resour. Res. 34, 2573–2585. https://doi.org/10.1029/98WR01285 (1998).

Rott, H. Advances in interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) in earth system science. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 33, 769–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133309350263 (2009).

Diao, X., Wu, K., Zhou, D. & Li, L. Integrating the probability integral method for subsidence prediction and differential synthetic aperture radar interferometry for monitoring mining subsidence in Fengfeng, China. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 10 https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JRS.10.016028 (2016).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Present-Day land subsidence rates, surface faulting hazard and risk in Mexico City with 2014–2020 Sentinel-1 IW InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 253, 112161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112161 (2021).

Haghshenas Haghighi, M. & Motagh, M. Ground surface response to continuous compaction of aquifer system in Tehran, Iran: results from a long-term multi-sensor InSAR analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 221, 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2018.11.003 (2019).

Khorrami, M., Abrishami, S., Maghsoudi, Y., Alizadeh, B. & Perissin, D. Extreme subsidence in a populated city (Mashhad) detected by PSInSAR considering groundwater withdrawal and geotechnical properties. Sci. Rep. 10, 11357. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67989-1 (2020).

Khoshlahjeh Azar, M. et al. Integrated analysis of Hashtgerd plain deformation, using Sentinel-1 SAR, geological and hydrological data. Sci. Rep. 12, 21522. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25659-4 (2022).

Hussain, M. A. et al. Sentinel-1A for monitoring land subsidence of coastal city of Pakistan using Persistent Scatterers In-SAR technique. Sci. Rep. 12, 5294. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09359-7 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Wang, C., Wang, M., Wang, Z. & Zhang, H. Surface deformation monitoring in Zhengzhou City from 2014 to 2016 using Time-Series InSAR. Remote Sens. 10, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10111731 (2018).

Wang, B., Zhu, L., Pan, D., Guo, L. & Peng, P. Research on temporal and spatial evolution law of land subsidence in Zhengzhou. Remote Sens. Land. Resour. 32, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.6046/gtzyyg.2020.03.19 (2020).

Ye, Y., Yan, C., Luo, X., Zhang, R. & Yuan, G. Analysis of ground subsidence along Zhengzhou Metro based on time series InSAR. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 26, 1342–1353. https://doi.org/10.11834/jrs.20211246 (2022).

Guo, H. et al. Large-scale land subsidence monitoring and prediction based on SBAS-InSAR technology with time-series Sentinel-1A Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 15, 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15112843 (2023).

Ghorbani, Z. et al. Use of InSAR data for measuring land subsidence induced by groundwater withdrawal and climate change in Ardabil Plain, Iran. Sci. Rep. 12, 13998. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17438-y (2022).

Cao, R., Liao, B., Li, M. & Sun, R. Predicting prices and analyzing features of online short-term rentals based on XGBoost. Data Anal. Knowl. Discovery. 6, 51–65. https://doi.org/10.11925/infotech.2096-3467.2020.1186 (2021).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (ACM, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

Cui, Z., Yang, P. & Zhang, Z. Comprehensive suitability evaluation of urban geological environment in Zhengzhou-Kaifeng area. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 4, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.26599/jgse.2016.9280024 (2016).

Ahmed Mohamed, Y. & Hamid Reza, P. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning algorithms and comparison of their performance at Abha Basin, Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Geosci. Front. 12, 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2020.05.010 (2021).

Gong, S. L., Li, C. & Yang, S. L. The microscopic characteristics of Shanghai soft clay and its effect on soil body deformation and land subsidence. Environ. Geol. 56, 1051–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1205-4 (2009).

Tomás, R. et al. A ground subsidence study based on DInSAR data: calibration of soil parameters and subsidence prediction in Murcia City (Spain). Eng. Geol. 111, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2009.11.004 (2010).

Cui, Z. D., Yang, J. Q. & Yuan, L. Land subsidence caused by the interaction of high-rise buildings in soft soil areas. Nat. Hazards. 79, 1199–1217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-1902-8 (2015).

Khorrami, M. et al. How groundwater level fluctuations and geotechnical properties lead to asymmetric subsidence: a PSInSAR analysis of land deformation over a transit corridor in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area. Remote Sens. 11, 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11040377 (2019).

Ferreira, V. G. et al. Space-based observations of crustal deflections for drought characterization in Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.277 (2018).

Murray, K. D. & Lohman, R. B. Short-lived pause in Central California subsidence after heavy winter precipitation of 2017. Sci. Adv. 4 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar8144 (2018).

Yu, B. et al. Monitoring subsidence rates along road network by persistent scatterer SAR interferometry with high-resolution TerraSAR-X imagery. J. Mod. Transp. 21, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-013-0030-y (2013).

Wu, W., Guo, S. & Shao, Z. Landslide risk evaluation and its causative factors in typical mountain environment of China: a case study of Yunfu City. Ecol. Ind. 154, 110821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110821 (2023).

Ren, Y., Zhang, F., Zhao, C. & Cheng, Z. Attribution of climate change and human activities to vegetation NDVI in Jilin Province, China during 1998–2020. Ecol. Ind. 153, 110415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110415 (2023).

Gao, M., Wu, Z., Guo, X. & Yan, D. Emergy evaluation of positive and negative benefits of agricultural water use based on energy analysis of water cycle. Ecol. Ind. 139, 108914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108914 (2022).

Vasco, D. W. et al. Using Sentinel-1 and GRACE satellite data to monitor the hydrological variations within the Tulare Basin, California. Sci. Rep. 12, 3867. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07650-1 (2022).

Castellazzi, P. et al. Quantitative mapping of groundwater depletion at the water management scale using a combined GRACE/InSAR approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 205, 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.11.025 (2018).

Yague-Martinez, N. et al. Interferometric processing of Sentinel-1 TOPS data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2015.2497902 (2016).

Werner, C. L., Wegmüller, U., Strozzi, T. & Wiesmann, A. Gamma sar and interferometric processing software. (2000).

Hooper, A., Segall, P. & Zebker, H. A. Persistent scatterer InSAR for crustal deformation analysis, with application to Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos. J. Phys. Res. 112 https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004763 (2007).

Tang, W. et al. Land subsidence and rebound in the Taiyuan basin, northern China, in the context of inter-basin water transfer and groundwater management. Remote Sens. Environ. 269, 112792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112792 (2022).

Yu, C., Li, Z., Penna, N. & Crippa, P. Generic Atmospheric correction model for interferometric synthetic aperture radar observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 123 https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JB015305 (2018).

Fu, Z. et al. Geographical types and driving mechanisms of Rural Hollowing-Out in the Yellow River Basin. Agriculture 14, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030365 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Land subsidence due to groundwater withdrawal in the northern Beijing plain, China. Eng. Geol. 193, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.04.020 (2015).

Zha, Y., Gao, J. & Ni, S. Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 24, 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431160304987 (2003).

Samat, A. et al. Mapping blue and red color-coated steel sheet roof buildings over China using Sentinel-2A/B MSIL2A images. Remote Sens. 14, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14010230 (2022).

Mitchell, B. & Chakraborty, J. Landscapes of thermal inequity: disproportionate exposure to urban heat in the three largest US cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 115005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/115005 (2015).

Xu, Y., Gong, H., Chen, B., Zhang, Q. & Li, Z. Long-term and seasonal variation in groundwater storage in the North China Plain based on GRACE. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 104, 102560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102560 (2021).

Yuill, R. S. The Standard Deviational Ellipse; an updated Tool for spatial description. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 53, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/490885 (1971).

Luo, Q., Perissin, D., Zhang, Y. & Jia, Y. L-and X-band multi-temporal InSAR analysis of Tianjin subsidence. Remote Sens. 6, 7933–7951. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs6097933 (2014).

Ni, J. et al. Quantifying the relationship between human activities intensity and thawing hazards of the Frozen Ground on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 845–873. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.845873 (2022).

Motagh, M. et al. Quantifying groundwater exploitation induced subsidence in the Rafsanjan plain, southeastern Iran, using InSAR time-series and in situ measurements. Eng. Geol. 218, 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.01.011 (2017).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant number U21A2014; the Key Laboratory of Geospatial Technology for Middle and Lower Yellow River Regions (Henan University), Ministry of Education open project, Grant number GTYR202203; the Natural Science Foundation of Henan province, Grant number 232300420432; Henan Provincial Key R&D and Promotion Special Project (Science and Technology Research), Grant number 242102321122 and the Key Scientific Research Projects of Higher Education Institutions of Henan province, Grant number 24A420002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z.Z. and J.H.; methodology, Z.Z. and J.H.; validation, T.Q. and Z.L.; investigation, S.C. and T.Q.; resources, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and J.W.; supervision, J.H. and J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Hu, J., Wang, J. et al. Identifying spatiotemporal pattern and trend prediction of land subsidence in Zhengzhou combining MT-InSAR, XGBoost and hydrogeological analysis. Sci Rep 15, 3848 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87789-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87789-9