Abstract

Several modifiable health factors in Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) are linked to nutritional anemia and can assess overall cardiovascular health (CVH). This study explored the associations of CVH measured by LE8 score with nutritional anemia and iron deficiency anemia (IDA), including the mediating role of inflammatory biomarkers. This prospective cohort study included 181,069 participants from UK Biobank. CVH was categorized into low (0–49), medium (50–79), and high (80–100) based on the LE8 score. Weibull regression models were used to quantify the association between CVH and nutritional anemia and IDA. During a median follow-up of 8.6 years, 6749 cases of nutritional anemia occurred, including 92% (6223/6749) IDA cases. After adjusting for covariates, participants with moderate CVH and high CVH had a 44% and 54% lower risk of nutritional anemia (Moderate: hazard ratio [HR] 0.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.60; High: HR 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), and a 46% and 54% lower risk of IDA (Moderate: HR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.50–0.59; High: HR 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), respectively, compared to those with low CVH. An L-shaped association was observed between CVH score and both types of anemia. Inflammatory biomarkers explained 22.1% and 21.6% of the associations between CVH and nutritional anemia and IDA, respectively. Higher CVH scores were associated with lower risk of nutritional anemia and IDA, and these associations may be partially mediated by inflammatory biomarkers. These findings emphasize the importance of CVH and inflammation in preventing nutritional anemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutritional anemia is a type of anemia caused by nutritional deficiencies, often due to a lack of nutrients involved in the formation of hemoglobin and red blood cells, including iron, vitamin B12, folic acid, etc. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common type of nutritional anemia,1,2 affecting approximately 2 billion people.3 Nutritional anemia is one of the common health problems worldwide.4 For adults, nutritional anemia may lead to various adverse health outcomes, such as reduced work ability,5 impaired physical function, and immune function.6,7 At the same time, studies have shown that nutritional anemia is related to various chronic diseases such as hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, myocardial infarction or angina, and rheumatoid arthritis.8,9 Therefore, it is necessary to consider multiple factors comprehensively to prevent and treat nutritional anemia.

The American Heart Association (AHA) recently updated the enhanced method for assessing cardiovascular health (CVH) and defined it as Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), which includes eight key health indicators: diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, sleep, BMI, non-HDL cholesterol, blood glucose, and blood pressure.10 There is growing evidence that several modifiable risk factors, including dietary patterns,11 underweight,12 sleep disorders,13 smoking14, obesity,15 and non-HDL cholesterol,16 are significantly associated with the risk of anemia, which are all components of LE8. However, to date, there is no comprehensive measure to assess the relationship between these factors and nutritional anemia and IDA risk. Clarifying the relationship between LE8 and nutritional anemia may help translate LE8 into effective preventive measures.

Furthermore, so far the mechanism of association between CVH and nutritional anemia remains unclear. Current studies have shown that single modifiable factors affecting CVH, such as maintaining a healthy weight,17 increasing physical activity,18 reducing smoking,19 and maintaining a healthy diet,20 can reduce the concentration of circulating inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell count (WBC). Of note, a recent study showed that the composite index LE8 score composed of these single factors also had a strong dose-response and negative correlation with CRP levels.21 Moreover, there is also evidence that inflammation may be one of the causes of anemia.22,23 Therefore, we hypothesized that LE8 may reduce the risk of nutritional anemia by reducing the levels of inflammatory biomarkers.

To address these research gap, our study aimed to firstly explore the longitudinal association between CVH and the risk of nutritional anemia and IDA using a large prospective cohort from the UK Biobank. Secondly, we investigated the extent to which inflammatory biomarkers (such as CRP and WBC) mediated these associations using mediation analysis.

Methods

Study design and population

This study utilized a large-scale prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank. From 2006 to 2010, health information was collected from 502,370 participants at 22 assessment centers in England, Scotland, and Wales through touch-screen questionnaires, physical examinations, and biological samples.24

A total of 189,706 participants with complete LE8 data were included in this study. Subsequently, we excluded 1750 participants with nutritional anemia at baseline, 2004 participants with incomplete covariate information, and 4883 participants with missing inflammatory biomarker information. A total of 181,069 participants were ultimately included in this study (Supplementary Fig. 1). The UK Biobank received full ethical approval from the National Health Service (NHS) (REC reference: 21/NW/0157) and all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants gave written informed consent. Additionally, the study complied with STROBE reporting guidelines.

Exposure: CVH score assessed by LE8

This study was based on the AHA guideline-revised CVH score (Supplementary Table 1).10 Briefly, LE8 consists of health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep) and health factors (BMI, non-HDL cholesterol, blood glucose, and blood pressure). Diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep were collected using a touchscreen standardized questionnaire. Data on health factors were collected by trained nurses according to a standardized protocol. The definition and detailed description of each indicator were provided in Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1, and Supplementary Table 2.

Each health indicator was scored on a scale of 0–100. The overall CVH score was the unweighted average of all eight component index scores, with scores ranging from 0 to 100. The higher the score, the healthier the cardiovascular system. In addition, according to the AHA recommendations, we also divided the CVH score into the following three categories: high CVH (80–100), moderate CVH (50–79), and low CVH (0–49).10

Outcome: nutritional anemia and IDA

The main outcomes of the current study were nutritional anemia and its subtype IDA. Cases of nutritional anemia (codes, D50-D53) and IDA (code, D50) were defined using ICD-10 codes. Hospital inpatient records were obtained by linking admissions to the NHS Information Center (England and Wales) and Scottish Morbidity Records (Scotland). Follow-up time was calculated from the date of enrollment into the assessment to the date of diagnosis, review date (September 30, 2023), or death, whichever occurred first.

Mediators: CRP and WBC

In this study, serum CRP levels (mg/L) were measured by Beckman Coulter AU5800 immunoturbidimetric high-sensitivity analysis at baseline. WBC levels (109 cells/Litre) were measured within 24 h after blood collection using Beckman Coulter LH750 hematology analyzer. CRP and WBC were transformed to approximate normal distribution using logarithmic transformation.

Covariates

Covariates in this study included age, sex (male, female), ethnicity (White, Asian or Asian British, Black or Black British, and Other), Townsend deprivation index (TDI), education attainment (College or university degree, Professional qualifications, and Others), alcohol consumption (daily, 3–4 times a week, 1–2 times a week, occasionally and never), and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Yes, No). More detailed information on these variables is available in the Supplementary Methods section and the UK Biobank website (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Statistical analysis

We summarized baseline characteristics by CVH category, including the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables, and compared them using chi-square tests or analysis of variance.

Using follow-up time as the time scale, we used Weibull regression models to verify the relationship between CVH score (per 10-point increment, categorized as low, medium, and high CVH) and nutritional anemia, including IDA. The Weibull proportional hazards assumption was assessed by evaluating the linear distribution between ln (-ln [survival probability]) and ln (survival time). Results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Three models were fitted: Model 1 was crude; Model 2 adjusted for age, sex; Model 3 additionally adjusted ethnicity, education level, TDI, alcohol consumption status, and baseline CVD.

Furthermore, we performed stratified analyzes by all covariates and assessed multiplicative interactions by adding interaction terms in the fully adjusted Weibull regression model. Subsequently, we used restricted cubic splines with 3 knots to explore the shape of the association between continuous CVH scores and the risk of nutritional anemia and IDA, with the lowest score as the reference group (HR = 1) and the model adjusted for all covariates.

Additionally, to verify the robustness of the results, we performed several sensitivity analyses. Firstly, all participants with a follow-up time of < 2 years were excluded from the reanalysis. Secondly, additional adjustment for baseline cancer was undertaken to reassess the associations. Thirdly, we re-analyzed the data by excluding people with a history of CVD. Fourthly, we explored the association between CVH and nutritional anemia using age as the time scale. Finally, the competing risk of non-nutritional anemia death on the association between CVH and nutritional anemia events was analyzed using the subdistribution hazard regression approach proposed by Fine and Grey.25

Mediation analysis of single inflammatory biomarkers was performed using the “mediation” package in R software.26 The effects were estimated using 1,000 nonparametric bootstrap simulations and quasi-Bayesian confidence intervals were constructed. In addition, inflammatory biomarkers with mediating effects were simultaneously included in the mediation model, and multiple mediation analysis was performed using the “lavaan” package in R27 to calculate the overall mediation effect of inflammatory biomarkers. Subsequently, longitudinal mediation analysis was performed using inflammatory biomarkers data from the first follow-up in 2012–2013. All covariates were adjusted in the mediation analysis models. The results were presented as mediation proportions and indirect effect estimates with their respective 95% CIs.

All analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.2 and Stata version 17.0. P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance (two-sided).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In this study, a total of 181,069 participants were included, and their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 56.40 (8.07) years, 48.34% were male, and 92.74% were White. The average CVH score was 67.98 (10.99), with low CVH score of 44.29 (4.71), moderate CVH score of 66.81 (7.60), and high CVH score of 84.42 (3.80). People with higher CVH scores were more likely to be female, have higher education levels, better socioeconomic status, lower CRP and WBC levels, and lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

CVH and nutritional anemia

There was a linear association between ln (-ln [survival probability]) and ln (survival time) (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), and the Weibull proportional hazard assumption was established. During the median follow-up period of 8.6 years, 6749 cases (3.7%) of nutritional anemia occurred, of which the incidence rates of nutritional anemia in low, medium and high CVH were 7.6%, 3.7% and 2.4%, respectively. In addition, 6233 cases (3.4%) of IDA occurred, of which the incidence rates of IDA in low, medium and high CVH were 7.1%, 3.4% and 2.2%, respectively (Supplementary Table 3).

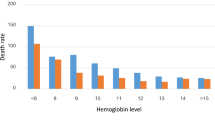

In Table 2, we observed that higher CVH score was significantly associated with lower risk of nutritional anemia and IDA. After adjusting for all covariates, every 10-point increase in CVH was associated with a significant 19% lower risk of nutritional anemia events (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.79–0.82) and a 19% lower risk of IDA (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.79–0.83). Compared with participants with low CVH, moderate CVH and high CVH groups had a 44% (HR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.51–0.60) and 54% (HR 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51) lower risk of developing nutritional anemia, respectively. Similarly, the risk of IDA was reduced by 46% (HR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.50–0.59) and 54% (HR 0.46; 95% CI, 0.41–0.51), respectively. The association of continuous CVH scores with the risk of nutritional anemia and IDA is shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4. Overall, the dose-response relationship between CVH score and the risk of nutritional anemia and IDA was L-shaped (all nonlinear P < 0.001).

Dose-response relationship between overall CVH score assessed by LE8 and the risk of nutritional anemia. The model was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, educational attainment, alcohol intake and baseline cardiovascular disease. The lowest score (17 score) as the referent score (estimated HR = 1.00). Abbreviations: LE8, Life’s Essential 8; CVH, Cardiovascular health; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Stratified analysis and sensitivity analysis

The results of multiple stratified analyses are shown in Fig. 2. The association between CVH and nutritional anemia and IDA was greater in individuals under college/university degree (P for interaction < 0.05). We did not find significant interactions between other factors and CVH levels on the risk of nutritional anemia and IDA (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Stratified analysis of the association between continuous CVH score assessed by LE8 and the risk of nutritional anemia and iron deficiency anemia. The model was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, educational attainment, alcohol intake, and baseline cardiovascular disease. CVH is measured on a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better cardiovascular health.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the association between CVH and nutritional anemia and IDA. Firstly, results were similar to the main analysis when all participants within 2 years of baseline were excluded (Supplementary Table 6). Additionally, we controlled for participants with cancer at baseline and found consistent associations between CVH and nutritional anemia and IDA (Supplementary Table 7). Thirdly, excluding individuals with a history of CVD did not significantly change the results (Supplementary Table 8). Fourthly, the results did not change substantially when the analysis was conducted using age as the time scale (Supplementary Table 9). Finally, the results of the competing risk analysis were also consistent with the primary analysis (Supplementary Table 10).

Mediating effect of inflammatory biomarkers

CVH was significantly negatively correlated with CRP and WBC levels (βCRP − 0.032; βWBC −0.044; P < 0.0001), while CRP and WBC were significantly positively correlated with nutritional anemia (βCRP 0.134; βWBC 0.247; P < 0.0001) and IDA (βCRP 0.125; βWBC 0.284; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 11 and 12). After controlling for potential confounders, both CRP and WBC significantly mediated the association between CVH and nutritional anemia, explaining 20.2% and 5.2% of the association, respectively, with an overall mediation ratio of 22.1% (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Similarly, a significant mediation effect was observed in the association between CVH and IDA, with CRP and WBC explaining 19.2% and 6.1%, respectively, with an overall mediation effect of 21.6% (P < 0.0001).

Path diagram of mediation analysis. (a) Mediating effect of inflammatory biomarkers on the association between CVH score assessed by LE8 and nutritional anemia. (b) Mediating effect of inflammatory biomarkers on the association between CVH score assessed by LE8 and iron deficiency anemia (IDA). The model was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, educational credentials, alcohol intake, and cardiovascular disease. Abbreviation: CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, White blood cell count; LE8, Life’s Essential 8; CVH, Cardiovascular health. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

Multiple mediating effects of inflammatory biomarkers (CRP and WBC) on the relationship between CVH score assessed by LE8 and nutritional and iron-deficiency anemia. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, educational credentials, alcohol intake, and cardiovascular disease. Abbreviation: CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, White blood cell count; LE8, Life’s Essential 8; CVH, Cardiovascular health. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

The results of longitudinal mediation analysis showed that CRP still significantly mediated the association between CVH and nutritional anemia, explaining 27.8%. However, no significant longitudinal mediation effect of WBC was observed. (Supplementary Table 13)

Discussion

In this large-scale prospective cohort study, we found an L-shaped association between CVH levels and nutritional anemia as well as its subtype IDA. For every 10-point increase in CVH, the risk of both nutritional anemia and IDA decreased by 19%. Compared with participants with low CVH, those with moderate and high CVH levels had a 44% and 54% lower risk of developing nutritional anemia and a 46% and 54% lower risk of IDA, respectively. Inflammatory biomarkers could partially explain these associations.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between CVH and the risk of nutritional anemia and found an inverse association. Based on previous studies and our findings, these associations may be related to changes in inflammatory biomarker levels. A recent study in Swedish showed a strong inverse correlation between LE8 scores and CRP levels,21 which is highly consistent with our findings. At the same time, we found that CRP and WBC were significantly positively associated with nutritional anemia and IDA. Studies have also shown that chronic inflammation can mediate the regulation of hepcidin and iron transport proteins, leading to ineffective iron transport to the bone marrow, thereby affecting erythropoiesis and causing iron deficiency anemia.28,29

Of note, studies have quantified the impact of some healthy lifestyle factors on nutritional anemia, which are important components of the CVH score. For example, sleep disorders, poor nutritional status, inadequate dietary intake, insufficient physical activity, and low body weight were also significantly associated with poor iron metabolism or nutritional anemia.12,13,30,31,32,33 Our study provides new evidence in this field by quantifying the burden of CVH status in developing nutritional anemia and further supports the protective effect of high CVH scores against nutritional anemia. In addition, we observed a significant synergistic effect between CVH and education level on the incidence of nutritional anemia, which emphasizes the necessity of lifestyle changes, especially for those with lower education levels who may benefit more from a healthier lifestyle.

Our study has a prospective, large sample size and long-term follow-up longitudinal design. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of CVH on nutritional anemia using a prospective cohort study design, filling the research gap in the relevant field. Second, this study was the first to use inflammatory biomarkers as mediators to explore the mediating effects of CRP and WBC on CVH on nutritional anemia. In addition, we investigated potential moderators and performed stratified analyses according to covariates, providing insights into how the association between CVH and nutritional anemia may differ among subgroups.

However, our study also has some limitations. Firstly, the health behavior indicators in LE8 were obtained based on self-reports, and there may be risks of recall bias or misclassification. Secondly, as a volunteer group, UK Biobank participants tend to be healthier and wealthier34 and may not be fully representative of the general UK population. Nonetheless, due to its large sample size and rich data, it can still be used to estimate exposure-disease relationships without affecting the analysis of internal validity.34,35 Thirdly, we excluded participants with missing data such as LE8 and covariates in the analysis. Even seemingly insignificant exclusions may affect the generalizability of the results. Future studies should further verify these findings and consider the applicability of a wider sample. Fourthly, outcome variables were defined using accurate case-diagnosis through record linkage. However, ICD-10 codes can only clearly identify diagnosed nutritional anemia and its subtypes and may not adequately capture mild or early anemia symptoms. Fifthly, extensive sensitivity analyses increased the rigor of the results. However, exclusion of participants with baseline cancer may have introduced collision bias. Finally, given that the manifestation of mediation effects may vary across populations, we believe that future studies should be validated in a wider population.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study, we found significant inverse associations between CVH scores and nutritional anemia and IDA, and inflammatory biomarkers may partially explain these associations. Our findings highlight that improving CVH levels may reduce the disease burden of nutritional anemia and IDA, which may be a potential combined approach to prevent these diseases.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the UK Biobank repository. Accessible at: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk.

References

Denic, S. & Agarwal, M. M. Nutritional iron deficiency: an evolutionary perspective. Nutrition. 23, 7–8 (2007).

Stoltzfus, R. Defining iron-deficiency anemia in public health terms: a time for reflection. J. Nutr. 131, 2s-2 (2001).

United Nations. Administrative Committee on Coordination Sub-Committee on Nutrition. Fourth report on the world nutrition situation.[J]. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/125335/filename/125336.pdf (2000).

Bhadra, P. & Deb, A. A review on nutritional anemia. Indian J. Nat. Sci. 10, 59 (2020).

Haas, J. D. & Brownlie IV, T. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J. Nutr. 131, 2 (2001).

Oppenheimer, S. J. Iron and its relation to immunity and infectious disease. J. Nutr. 131, 2 (2001).

Beard, J. L. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism and neuronal functioning. J. Nutr. 131, 2 (2001).

Silverberg, D., Iaina, A., Wexler, D. & Blum, M. The pathological consequences of anaemia. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 23, 1 (2001).

Park, S. H., Han, S. H. & Chang, K. J. Comparison of nutrient intakes by nutritional anemia and the association between nutritional anemia and chronic diseases in Korean elderly: based on the 2013–2015 Korea national health and nutrition examination survey data. Nutr. Res. Pract. 13, 6 (2019).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 146, 5 (2022).

Xu, X., Hall, J., Byles, J. & Shi, Z. Dietary pattern, serum magnesium, ferritin, C-reactive protein and anaemia among older people. Clin. Nutr. 36, 2 (2017).

Khan, Z. A., Khan, T., Bhardwaj, A., Aziz, S. J. & Sharma, S. Underweight as a risk factor for nutritional anaemia–A cross-sectional study among undergraduate students of a medical college of haryana. Indian J. Community Med. 30, 1 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Night sleep duration and risk of incident Anemia in a Chinese population: a prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 8, 1 (2018).

Waseem, S. M. A. & Alvi, A. B. Correlation between anemia and smoking: Study of patients visiting different outpatient departments of Integral Institute of Medical Science and Research, Lucknow. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 10, 2 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Causal relationship between obesity and iron deficiency anemia: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Public Health. 11 (2023).

Fessler, M. B., Rose, K., Zhang, Y., Jaramillo, R. & Zeldin, D. C. Relationship between serum cholesterol and indices of erythrocytes and platelets in the US population. J. Lipid. Res. 54, 11 (2013).

Ferrante Jr, A. Obesity‐induced inflammation: a metabolic dialogue in the language of inflammation. J. Internal. Med. 262, 4 (2007).

Kasapis, C. & Thompson, P. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein and inflammatory markers: A systemic review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 10 (2005).

Yanbaeva, D. G., Dentener, M. A., Creutzberg, E. C., Wesseling, G. & Wouters, E. F. Systemic effects of smoking. Chest. 131, 5 (2007).

Ajani, U. A., Ford, E. S. & Mokdad, A. H. Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings from national health and nutrition examination survey data. J. Nutr. 134, 5 (2004).

Hebib, L. et al. Life’s Essential 8 is inversely associated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Sci. Rep. 14, 1 (2024).

Yip, R. & Dallman, P. R. The roles of inflammation and iron deficiency as causes of anemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 48, 5 (1988).

Ramel, A., Jonsson, P. V., Bjornsson, S. & Thorsdottir, I. Anemia, nutritional status, and inflammation in hospitalized elderly. Nutrition. 24, 11–12 (2008).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, 3 (2015).

Fine, J. P. & Gray, R. J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 446 (1999).

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L. & Imai, K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 1548–7660 (2014).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48 (2012).

Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron homeostasis and the inflammatory response. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 1 (2010).

Cappellini, M. D. et al. Iron deficiency across chronic inflammatory conditions: International expert opinion on definition, diagnosis, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 92, 10 (2017).

Bianchi, V. E. Role of nutrition on anemia in elderly. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 11 (2016).

Paramastri, R. et al. Association between dietary pattern, lifestyle, anthropometric status, and anemia-related biomarkers among adults: a population-based study from 2001 to 2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7 (2021).

Paramastri, R., Hsu, C.-Y., Lee, H.-A. & Chao, J. Interactions of lifestyle factors on the risk of anemia among Taiwanese adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 5 (2021).

Jackowska, M., Kumari, M. & Steptoe, A. Sleep and biomarkers in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing: associations with C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and hemoglobin. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 9 (2013).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 9 (2017).

Batty, G. D., Gale, C. R., Kivimäki, M., Deary, I. J. & Bell, S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. BMJ. 368 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using UK Biobank resources under application No.95715. The authors gratefully thank all the participants and professionals contributing to the UK Biobank.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and D.Z. conceived the study. J.W., W.W., and D.Z. wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. J.W. and X.Q. were responsible for acquiring, analyzing, or interpreting the data. X.Q., G.W., and W.W. were responsible for study conceptualization, and X.Q. and G.W. were responsible for visualization. D.Z. and J.W. had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

Full ethical approval for UK Biobank was obtained from the North West Haydock Research Ethics Committee (IRAS project ID, 299116). All participants provided informed consent to participate in UK Biobank.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Qi, X., Wang, G. et al. Association of life’s essential 8 and inflammatory biomarkers with nutritional anemia in UK adults. Sci Rep 15, 3177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87823-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87823-w