Abstract

In this study, patients with inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) who visited Ningxia Eye Hospital from January 2015 to September 2023 were analyzed. Through Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and Sanger verification, 17 probands carrying homozygous variants were detected. The association between the genotype and clinical phenotype of patients with homozygous variants was analyzed. Among all the patients, 3 patients (17.6%) had a family history of consanguineous marriage, and the onset age of 5 patients(29.4%) was less than 10 years. According to 12 patients (70.6% ), they had the best corrected visual acuity (monocular) < 0.3. 3 were blind, 9 with moderate to severe visual impairment, and 2 with mild visual impairment. 16 homozygous variants were detected in 9 different genes, of which 7 were novel homozygous variants, including frameshift variants, missense variants, and a copy number variant. These variants are related to clinical phenotypes such as Usher syndrome type II (USH2), Stargardt disease (STGD), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) respectively. The results of the study indicate that more than 80% of persons with homozygous variant originated from non-consanguineous families, emphasizing the significance of genetic screening for individuals who lack a family history of consanguineous marriage and no obvious clinical phenotypes, but who may carry genetic pathogenic variants for genetic diseases. Furthermore, by analyzing the genotypes and clinical phenotypes of IRD patients from these 17 Chinese families, we have expanded the spectrum of variants in known pathogenic genes for IRDs and the range of clinical phenotypes associated with variants in these genes. We have identified couples at high risk of having affected offspring and individuals with moderate to severe IRDs, providing a basis for genetic counseling, reproductive decision-making, disease prevention, and management. Our findings highlight the association between homozygous variants and more severe clinical phenotypes within these families, thus laying the groundwork for future genetic screening and intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

IRDs are the most common and serious clinical blinding eye disease, and the leading cause of blindness in children and young adults worldwide1, for which there is no effective treatment yet. The incidence of IRDs is about 1:4000 in developed countries2, and in China, epidemiological surveys show that the incidence of RP is as high as 1:1000 in people over 40 years old3. Currently, there are still the following problems in the clinical diagnosis of IRDs: numerous pathogenic genes, complex and diverse clinical phenotypes, intricate relationships between genotypes and clinical phenotypes, and the lack of professional genetic knowledge among ophthalmologists lead to misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis, and mistreatment of a large number patients with IRDs. Therefore, the prerequisite for achieving IRD gene therapy is to identify the pathogenic genes and make an accurate diagnosis. The ClinGen guidelines state that two evidences are supporting the genetic link to disease: genetics (e.g. case studies) and experiments (e.g. animal models)4,5. To demonstrate the superiority of genetic evidence, the maximum score of experimental evidence (6 points) was only half that of gene evidence (12 points). This highlights the importance of reporting more cases with the same clinical phenotype to increase the credibility of the gene-disease association. Patients with a homozygous variant will transmit one variant to their offspring. Therefore, for certain genetic diseases with higher incidence rates, screening tests for individuals who may carry pathogenic variants of genetic disease genes, especially when there is a patient with a homozygous variant in the family, is an effective method to reduce the incidence of these hereditary diseases. In this study, the genotypes and clinical phenotypes of 17 IRD patients who carry homozygous variants were studied, and we performed screening tests on IRD probands’ parents who carried homozygous variants. The aim is to expand the spectrum of IRD pathogenic gene variants, and investigate the relationship between homozygous variants and clinical phenotypes of IRDs, to provide a basis for genetic counseling, reproductive decision-making, disease prevention, and management.

Results

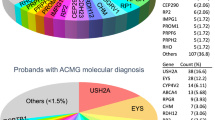

In this study, a total of 148 families with hereditary retinal diseases were collected, with clinical diagnoses including USH II, STGD, RP, LCA, BBS, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR), cone dystrophy (COD), cone-rod dystrophy (CORD), congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB), gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina, rod-cone dystrophy syndrome, Stickler syndrome, oculocutaneous albinism (OCA), and achromatopsia (ACHM). Among them, 66 families 66 families carried variants in 9 genes including CYP4V2, USH2A, etc. Variants in the USH2A and ABCA4 genes were more common in these cases, while the PROM1 and CNGA1 genes had the highest proportion of homozygous variants, with a total of 17 patients carrying homozygous variations included. 17 patients with homozygous variants were collected, and 3 had a family history of consanguineous marriage. The average age was 21.2 years old (ranging from infancy to 51 years). 29.4% (5/17) of patients developed symptoms before 10 years. The best-corrected visual acuity (in one eye) of 70.6%(12/17) patients was less than 0.3 and 35.3% (6/17) with best-corrected visual acuity (in one eye) better than 0.5 (Table 1). According to the visual impairment standards established by WHO in 2019, 3 were blind, 9 had moderate to severe visual impairment, 3 had mild visual impairment, and 2 were close but did not meet the criteria for visual impairment. A total of 16 variants were detected in 17 patients, in 9 genes: USH2A, CYP4V2, PROM1, RP1, CNGA1, PRPH2, ABCA4, CRB1, and BBS9, which were involved in 6 inherited retinal diseases: RP, USH, Bietti crystalline chorioretinal dystrophy (BCD), STGD, LCA, and BBS. This study identified 7 novel variants: including 4 frameshift variants - c.10179del; p.(Met3393*) of USH2A, c.544dupC; p.(Gln182*) of PROM1, c.265del; p.(Leu89Phefs*4) and c.253del; p. (Leu85Phefs*4) of CNGA1; 2 missense variants - c.1363G > C; p.(Gly455Arg) of PROM1, c.1363G > C; p.(Gly455Arg) of PRPH2; and 1 copy number variant - copy number loss of BBS9 located in the region of chr7. 33,404,663–33,409,821 (Table 2), all of which were pathogenic/likely pathogenic (Table 3). The clinical diagnosis was USH2, STGD, RP, LCA, and BBS respectively. The parents of all the probands had normal clinical phenotypes and carried the same heterozygous variants of the above-mentioned related genes. Through detailed analysis of homozygous regions in 14 probands, we obtained the following results: among them, the significant homozygosity percentage of 9 probands was below 6%, and the causal variants of 10 probands were located within homozygous regions. Among these 10 probands, the causal variants of 8 probands were in homozygous regions that rank in the top five in size among all homozygous regions (Table 4).

Analysis of the pathogenicity and clinical phenotypes of newly identified homozygous variants

Family 4

The proband was a 39-year-old male, who complained of progressive binocular vision loss accompanied by night blindness for 19 years, and he denied family history and consanguineous marriage history. The BCVA was 0.3 in the right eye and 0.4 in the left eye (Table 1). No abnormalities were observed in the anterior segment of both eyes. The fundus examination revealed the boundaries of the optic discs were clear and the color was waxy yellow, with no reflection in the macular fovea, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina. OCT showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone of the fovea, along with the atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. ERG showed significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, the proband carried a homozygous frameshift variant c.10179del; p.(Met3393*) in the USH2A gene, which resulted in a premature translational-termination codon (PTC) due to a frameshift at the 3393 codon (Fig. 1). According to the ACMG guidelines, the frameshift variant was considered as Pathogenic Very Strong (PVS1), while the absence of this variant in the normal population database was considered as Pathogenic Moderate (PM2), the proband’s clinical symptoms were consistent with USH, a monogenic disease, which was considered as Pathogenic Supporting (PP4). Therefore, the variant c.10179del; p.(Met3393*) was classified as Pathogenic (PVS1 + PM2 + PP4). The proband had poor hearing since childhood and was eventually diagnosed as USH II.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 4: (A) Pedigree of the family 4: The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (C) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was waxy yellow, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina, OCT showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone of fovea, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. (D) ERG: Significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. (E) The homology of amino acid sequences between human USH2A and other species, the amino acid at positions 3393 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 3393 is boxed and indicated.

Family 7

The proband of family 7, at the age of 7, complained of progressive bilateral vision reduced, and his parents denied family history and consanguineous marriage history. BCVA was 0.25 in the right eye and 0.15 in the left eye (Table 1). The anterior segment was normal and fundus examination showed pale optic discs with clear borders in both eyes. No reflection in the macular fovea, oval atrophy, and yellowish-white patchy exudation were observed in the macular area, showing a bull’s-eye change. OCT indicated a significant thinning of the macular fovea, disappearance of the outer nuclear layer and ellipsoid zone, and atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Fundus angiography reveals ‘worm-eaten-like’ fluorescent spots around the macular region. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, a homozygous frameshift variant c.544dupC; p.(Gln182*) was detected in PROM1 of the proband (Fig. 2). According to the ACMG guidelines, the frameshift variant was considered as Pathogenic Very Strong (PVS1), the variant was not detected in the normal population database or the known variant databases was considered as Pathogenic Moderate (PM2), the proband’s clinical symptoms were consistent with STGD, a monogenic genetic disease, which was considered as Pathogenic Supporting (PP4). Therefore, such a variant was classified as pathogenic (PVS1 + PM2 + PP4) based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. The proband was finally diagnosed with STGD.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 7: (A) Pedigree of the family 7: The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was pale in both eyes, oval atrophy and yellowish-white patchy exudation were observed in the macular area, showing a bull’s-eye change, OCT indicated a significant thinning of the macular fovea, disappearance of the outer nuclear layer and ellipsoid zone, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, fundus angiography reveals ‘worm-eaten-like’ fluorescent spots around the macular region. (C) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (D) The homology of amino acid sequences between human PROM1 and other species, the amino acid at positions 182 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 182 is boxed and indicated.

Family 8

The proband of family 8 was a 32-year-old female who presented with bilateral vision loss accompanied by night blindness for 17 years, and she denied any family history or consanguineous marriage history. BCVA was CF in the right eye and HM in the left eye (Table 1). The anterior segment was normal and fundus examination showed the waxy yellow optic discs with clear borders in both eyes. No reflection in the macular fovea, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina. OCT showed mild thinning of the macular region. ERG indicated significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, a homozygous missense variant c.1363G > C; p.(Gly455Arg) was detected PROM1 gene of the proband and his parents carried the same heterozygous variant respectively. This variant resulted in a change of the 455th codon from encoding glycine to encoding arginine (Fig. 3). According to the ACMG guidelines, this variant was not detected in the normal population database or in the known variant databases, which was considered as Pathogenic Moderate (PM2). Moreover, proteomics conservation analysis suggested that the p.(Gly455Arg) variant results in the substitution of a nonpolar, uncharged glycine at site 455 with a nonpolar, positively charged arginine. The N atom of the main chain forms a hydrogen bond with the O atom of the large, nonpolar, uncharged phenylalanine at site 451, with a hydrogen bond distance of 3.0 Å (the distances of normal protein structures is 2.9 Å). The O atom of the main chain forms a hydrogen bond with the N atom of the nonpolar, uncharged glycine at site 459, with a hydrogen bond distance of 2.7 Å (the distances of normal protein structures is 3.0 Å). These changes in amino acid interactions lead to alterations to the structure and function of the protein after the variant (Fig. 3). A variety of bioinformatics computing software indicated the deleterious impact of this variant (PP3_Supporting) (Table 3). The genotype and clinical phenotypic co-segregation in family members were considered as supportive evidence (PP1), the phenotype of the variant carriers was highly consistent with the monogenic genetic disease (RP), which was considered supportive evidence (PP4), gene testing report from a reliable and authoritative source considered this variant as Pathogenic, which serves as additional supportive evidence (PP5). Therefore, such a variant was classified as Pathogenic (PM2 + PP3 + PP1 + PP4 + PP5) based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. The problem was ultimately diagnosed with binocular RP.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 8: (A) Pedigree of the family 8: The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was waxy yellow, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina, OCT showed mild thinning of the macular region. (C) ERG: Significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. (D) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (E) Proteomic conservation analysis suggested that the p.G455R variant results in the substitution of a nonpolar, uncharged glycine at site 455 with a nonpolar, positively charged arginine, which leads to alterations to the structure and function of the protein after the variant. (F) The homology of amino acid sequences between human PROM1 and other species, the amino acid at positions 455 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 455 is boxed and indicated.

Family 12

The proband of family 12 was a 51-year-old female, who complained of progressive night blindness and vision decline for 20 years in both eyes, and she denied family history and consanguineous marriage history. BCVA was 0.5 in the right eye and 1.0 in the left eye (Table 1). No abnormalities were observed in the anterior segment of both eyes. Fundus examination showed the waxy yellow optic discs with clear borders in both eyes. No reflection in the macular fovea, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina. OCT showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone at the macular center in the right eye, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. ERG showed significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, a homozygous frameshift deletion variant c.265del; p.(Leu89Phefs*4) was detected in the CNGA1 gene of the proband, which led to a premature stop codon at position 4 of the new reading frame, and caused a frameshift beginning with codon Leucine 89, changing this amino acid to a Phenylalanine. The daughter of the proband carried the same heterozygous variant with normal clinical phenotype (Fig. 4). According to the ACMG guidelines, this variant was considered as Pathogenic Very Strong (PVS1), the variant was not detected in the normal population database or in the known variant databases and was considered as Pathogenic Moderate (PM2), The genotype and clinical phenotypic co-segregation in family members was considered as supportive evidence (PP1). The proband’s clinical symptoms were consistent with RP, a monogenic genetic disease, which was considered Pathogenic Supporting (PP4). Therefore, such a variant was classified as Pathogenic (PVS1 + PM2 + PP1 + PP4) based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. The proband was diagnosed with binocular RP.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 12: (A) Pedigree of the family 12:The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was waxy yellow in both eyes, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina, OCT showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone at the macular center in the right eye, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. (C) ERG: Significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. (D) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (E) The homology of amino acid sequences between human CNGA1 and other species, the amino acid at positions 89 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 89 is boxed and indicated.

Family 13

The proband of family 13 was a 20-year-old male, who complained of the left eye blurred vision accompanied by night blindness, and he denied family history and consanguineous marriage history. BCVA was 0.8 in the right eye and 0.1 in the left eye (Table 1). Exotropia in both eyes, with IOL in the left eye. Fundus examination showed the waxy yellow optic discs with clear borders in both eyes. No reflection in the macular fovea, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina. OCT examination showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone at the macular center, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in the left eye. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, a homozygous frameshift deletion variant c.253del; p.(Leu85Phefs*4) was detected in the CNGA1 gene of the proband, which led to a premature stop codon at position 4 of the new reading frame, and caused a frameshift beginning with codon Leucine 85, changing this amino acid to a Phenylalanine. The mother of the proband carried the same heterozygous variant with normal clinical phenotype (Fig. 5). According to the ACMG guidelines, this variant was Pathogenic Very Strong (PVS1), the variant was not detected in the normal population database or in the known variant databases and was considered as Pathogenic Moderate (PM2). The proband’s clinical symptoms were consistent with RP, a monogenic genetic disease, which was considered Pathogenic Supporting (PP4). Therefore, such a variant was classified as Pathogenic (PVS1 + PM2 + PP4) based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. The proband was ultimately diagnosed with binocular RP.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 13: (A) Pedigree of the family 13:The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was waxy yellow in both eyes, the retinal vessels were attenuated, and bone spicule-like pigment deposits were visible on the peripheral retina, OCT examination showed the disappearance of the light reflection signals in the local ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone at the macular center, along with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in the left eye. (C) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (D) The homology of amino acid sequences between human CNGA1 and other species, the amino acid at positions 85 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 85 is boxed and indicated.

Family 14

The proband of family 14 was a 6-year-old male, whose parents complained that the proband had poor vision in both eyes since childhood, they denied family history and consanguineous marriage history. BCVA was 0.02 in both eyes (Table 1). The proband exhibited horizontal nystagmus in both eyes, difficulty fixation, and eye poking, with no obvious abnormalities observed in the anterior segment. Fundus examination showed the boundaries of the optic discs were clear and the color was pale, the light reflection of the foveal centralis was not visible. OCT examination showed a mild elevation of the ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone in the macular region of the right eye. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, the homozygous variant c.640T > A; p.(Cys214Ser) was detected in the PRPH2 gene of the proband, which resulted in a change of 214th codon from encoding Cysteine to Serine (Fig. 6). According to the ACMG guidelines, this variant was not detected in the normal population database or in the known variant databases, which was considered as Pathogenic Moderate(PM2). A variety of bioinformatics computing software indicated the deleterious impact of this variant (PP3_Supporting)., Moreover, proteomic conservation analysis suggested that the p.(Cys241Ser) variant results in the substitution of a polar, uncharged cysteine at site 241 with a polar, uncharged serine. The N atom of the main chain and the hydroxyl group of the side chain form hydrogen bonds with the O atom of the nonpolar, uncharged phenylalanine at site 211, with hydrogen bond distances of 3.2 and 2.7 Å (the distances of normal protein structures are 3.1 Å). The O atom of the main chain forms a hydrogen bond with the N atom of the side chain of the nonpolar, uncharged tryptophan at site 246, with a hydrogen bond distance of 3.1 Å (the distances of normal protein structures is 3.2 Å). These changes in amino acid interactions lead to alterations in the structure and function of the mutated protein (Fig. 6). The genotype and clinical phenotypic co-segregation in family members was considered as supportive evidence (PP1), the proband’s clinical symptoms were consistent with LCA, a monogenic genetic disease, which was considered as Pathogenic Supporting (PP4), gene testing report from a reliable and authoritative source considered this variant as Pathogenic, which serves as additional supportive evidence (PP5). Therefore, such a variant was classified as Pathogenic (PM2 + PP1 + PP3 + PP4 + PP5) based on the standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. The proband was ultimately diagnosed with binocular LCA.

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 14: (A) Pedigree of the family 14: The filled black symbol represents the affected member, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: The color of the optic was pale, OCT showed a mild elevation of the ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone in the macular region of the the right eye. (C) Sequence chromatograms of identified variants. (D) The homology of amino acid sequences between human PRPH2 and other species. The amino acid at positions 214 is highly conserved among species, and the mutated residues 214 is boxed and indicated. (E) Proteomic conservation analysis suggested that the p.C241S variant results in the substitution of a polar, uncharged cysteine at site 241 with a polar, uncharged serine, which leads to alterations in the structure and function of the mutated protein.

Family 17

The proband of family 17 was a 7-year-old female, whose parents complained that the proband had decreased vision in both eyes accompanied by night blindness since childhood, her parents were consanguineously married. Ophthalmologic examination: BCVA was 0.15 in the right eye and 0.1 in the left eye, the axial length of right eye and left eye were 25.36 mm and 25.56 mm, respectively. The proband exhibited horizontal nystagmus accompanied by exotropia in both eyes. Fundus examination showed the boundaries of the optic discs were clear with normal color, fundus tessellation with no light reflection of foveal centralis. OCT examination showed no obvious structure of the fovea centralis (Fig. 7). ERG showed significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. The proband was born with hexadactyly in both hands and surgical treatment had been performed. At the age of 7, the proband was 133 cm in height, 44 kg in weight, and body mass index (BMI) was 24.87 kg/m2. The proband’s parents complained that she usually had poor memory and slow response, and the intelligence test suggested subnormal intelligence. As validated by the WES and Sanger sequencing, a homozygous deletion located in the region of chr7:33404663–33,409,821 was found in the BBS9 gene of the proband. The size of the homozygous deletion was 5159 bp, which covered exon 17, part of intron 16, and part of intron 17 in the BBS9 gene, resulting in an alteration in protein length. It was confirmed from Sanger sequencing analysis that the BBS9 gene variant was homozygous in affected individuals and heterozygous carriers in normal parents, supporting autosomal recessive inheritance (Fig. 7). The proband was eventually diagnosed with BBS. This variant does not disrupt the reading frame but likely results in a possible change in protein length. Such copy number deletion variant, being nonpolymorphic, was not found in the DGV Normal Population Copy Number variant Database. No copy number variants with a similar segment size were found in the Decipher database. According to the ACMG guidelines, such deletion is of uncertain significance. The structural comparison revealed that the overall structural superposition of the mutant and wild-type proteins is quite good, with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value of 2.424 Å between the proteins. Sequence alignment showed significant changes in the 566–598 structural region between the wild-type and mutant proteins, where the mutant lacks two α-helices and two β-sheets, resulting in the shortening of the β-sheets both preceding and following this region (Fig. 7F).

variant sequence analysis and clinical examination of the family 17: (A) Pedigree of the family 17: The filled black symbol represents the affected member, double horizontal lines indicate consanguineous marriage, and the arrow denotes the proband. (B) The fundus of both eyes: OCT examination showed no obvious structure of the fovea centralis. (C) ERG: Significant impairment of cone and rod cell function in both eyes. (D) Atient appearance: Epicanthus, wide eye distance, overweight, exotropia, hands have been polydactyly surgery. (E) Breakpoint analysis report and QPCR analysis chart. (F) The overall structural alignment between the mutant and wild-type proteins is quite good, with significant changes observed in the 566–598 structural region of the wild-type and mutant proteins. The mutant is missing two α-helices and two β-sheets, which leads to the shortening of the β-sheets both before and after this region.

Discussion

In autosomal recessive diseases, homozygous variants typically result in severe symptoms. In previous studies, it has been found that patients with homozygous mutations often come from families with consanguineous marriages15,16,17, our study found that over 80% of our patients’ parents were unrelated. This suggests that certain variants may be more common in the general population. When both parents carry the same recessive variant, their children can inherit both variants and they will be homozygous, leading to conditions like intellectual disabilities and developmental delays. Genetic drift and founder effects may render certain variants to become relatively frequent in subpopulations. The chance that unrelated parents then carry such a variant is not so low. Although consanguineous marriages can be reduced through social measures18, preventing homozygous variants in offspring from unrelated couples is more challenging. Identifying common variants in the population is key to preventing genetic diseases. Genetic counseling and testing can inform couples about their genetic risks, helping to predict and reduce their offspring’s disease risk, including through preconception and prenatal services19. Carrier screening is now highly valued for identifying asymptomatic individuals carrying pathogenic variants, further lowering the offspring’s disease risk. Deeper research into gene-disease relationships is vital for preconception carrier screening.

7 new variants were identified in this study. Previous studies have shown that the short isoform a of the USH2A gene is expressed in the retina and the cochlea, whereas the long isoform b is expressed only in the retina20. The Protein Truncating variants lead to premature termination of translation and result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay causing truncation or even deletion of proteins, which potentially leads to more severe phenotypes compared to protein changes caused by missense variants21,22. In this study, a new homozygous frameshift variant c.10179del; p.(Met3393*) was detected in the USH2A gene in the Family 4 Proband, and the patient was diagnosed with USH because of the clinical presentation of RP combined with deafness.

In the retina, PROM1 is mainly located in the outer segment of the retinal photoreceptor and plays a key role in the morphogenesis of the photoreceptor outer segment membrane discs23. Throughout literature, PROM1 variants have been associated with multiple diseases with overlapping phenotypes, such as RP, CORD, Stargardt-like macular dystrophy, bull’s-eye macular dystrophy, and LCA24,25. Depending on the type of variants, the age of onset, initial symptoms, and severity of the disease can vary among patients. In this study, two probands carrying the PROM1 gene variant had chief complaints of reduced vision and night blindness, respectively, and were diagnosed with Stargardt’s disease and RP, respectively, in combination with fundus and ERG examinations. The PROM1 gene variant can be inherited in both recessive and dominant patterns26. As compared with the retinal dystrophies caused by dominant PROM1 gene variants, the patients with retinal dystrophies associated with recessive PROM1 gene variants, such as CORD and LCA, have an earlier age of onset, more severe clinical phenotype, and can present with vision decline at an early stage of the disease25, which is highly consistent with the clinical phenotypes of the patients in this study. Homozygous frameshift deletion variant c.265del; p.(Leu89Phefs*4) and c.253del; p.(Leu85Phefs*4) of CNGA1 were detected in the probands of Family 12 and Family 13, and they were clinically diagnosed as RP. As shown by previous studies, variants in this gene are strongly associated with RP. This study further expands the spectrum of variants of the CNGA1 gene. Diseases caused by variants of the PRPH2 gene are mostly dominantly inherited and only a few are autosomal recessive inheritance27. Currently, only one case of autosomal recessive RP due to the PRPH2 gene has been reported, but the detailed clinical manifestations of this patient have not been reported28. In this study, the homozygous missense variant c.640T > A; p.(Cys214Ser) was detected in the PRPH2 gene of Family 14 Proband. The affected child had poor binocular vision since childhood, with a BCVA of 0.02 in both eyes at the age of 6, but did not show any symptoms of night blindness. Due to the overlap of phenotypes, it is easy to ignore the differentiation between RP and LCA. However, patients with LCA usually have severe visual impairment at birth, and the lesion often involves the outer retina, combined with the symptoms of binocular horizontal nystagmus, difficulty fixation, and eye poking, the patient in this case was diagnosed with LCA. Patients carrying a heterozygous variant of the PRPH2 gene generally have an age of onset after 30 years old29,30. The patient in this case was born with visual impairment, which may be preliminary inferred that patients with homozygous variants of the PRPH2 gene have an earlier age of onset and a more severe clinical phenotype. This study further confirmed that variants in the PRPH2 gene can lead to recessive IRDs.

The BBSome complex is a key regulator of the ciliary membrane proteome, which is mainly involved in the process of ciliogenesis and intraflagellar transport31. The protein encoded by the BBS9 gene is an important component of ciliary structure. In previously reported cases, BBS9-related diseases only led to BBS32. The proband of family 17 in this study presented typical BBS at the first visit, and a homozygous deletion in the chr7:33404663–33,409,821 region of the BBS9 gene was detected in the WES. To further clarify such a variant, we verified it by real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (qPCR). So far, there are almost no reports of BBS9 copy number variant, and most reports are mainly homozygous variants. The patients exhibit polydactyly, obesity, intellectual disability, and associated ocular symptoms such as vision loss, night blindness, and nystagmus from early childhood32,33,34, which are reported to be similar to the phenotype of the proband of family 17. There are still 30–40% of IRDs that cannot be explained by routine genetic testing, of which copy number variants account for 9%35,36. Therefore, in genetic diagnosis, when WES shows negative results, and the patient has a suspicious clinical phenotype, other different forms of variants, such as copy number variants, should be further considered to identify the pathogenic variant.

In this study, we found that homozygous variants have a higher incidence rate in non-consanguineous families, suggesting that heterozygous variants of some genes may have a higher carrier rate in the general population. We also identified seven new pathogenic variants and analyzed their potential mechanisms of pathogenicity, emphasizing the significant impact of copy number variants on disease occurrence. Our research provides stronger supporting evidence for the association between Mendelian disease variants and clinical phenotypes and highlights the importance of screening for carriers who have no family history of consanguineous marriages and no obvious phenotype of genetic disease. Timely detection of couples at high risk of having children and individuals with moderate or severe IRDs is crucial for genetic counseling, reproductive decision-making, disease prevention, and management.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved and reviewed by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (No. 2022-KJCG-006). In this study, we need to publish the facial information of participants to support the presentation of research results, and all participants included in the study obtained informed consent from the patients or their legal guardians and signed the relevant informed consent forms. We have taken measures to protect the privacy of participants, including but not limited to anonymization processes and restricting access to the information. Participants have the right to withdraw their consent at any time, and we will immediately cease the use of their facial information and remove it from published materials where possible. The publication of facial information in this study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research at People’s Hospital in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. This study included a total of 17 patients diagnosed with IRDs from January 2015 to September 2023 in Ningxia Eye Hospital and they were confirmed to carry homozygous variants by WES. The current medical history, past medical history, personal history, family history, and marital history of the probands were asked and recorded in detail, and the family tree was drawn.

Clinical evaluation

The complete ophthalmic examinations were performed on IRD patients, including slit-lamp microscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), chromoscopy (Fifth Edition Color Blindness Examination Chart, Zi-Ping Yu), scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Optos DaytonaP200T), fundus photography (TOPCON, Japan, TRC-NW300), optical coherence tomography (OCT) (HD-OCT4000, Carl Zeiss Meditec, USA), electroretinogram (Roland Consult Stasche, Finger GumbHD-14770, Germany), perimetry (Humphrey Field Analyzer 750i, Germany). According to the patient’s clinical phenotype and the characteristics of pathogenic genes, the necessary general examinations were performed, such as hearing tests, etc. Diagnostic criteria for visual impairment: According to the visual impairment standards established by WHO in 201937, the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of the better-seeing eye is less than 0.5 but equal to or greater than 0.3is classified as mild visual impairment, if which being less than 0.3 but equal to or greater than 0.1, it is classified as moderate visual impairment, if which being less than 0.1 but equal to or greater than 0.05, it is classified as severe visual impairment, and if which is less than 0.05 is classified as blindness.

Methods

Genomic DNA extraction

5 ml of peripheral venous blood was collected from all participants, and genomic DNA was extracted by using the Qiamp Blood Mini Kit DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany) with standard protocol after the concentration and purity were detected by UV spectrophotometer and 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, stored the DNA in a -20 °C refrigerator.

Whole exome sequencing

Whole exome sequencing (WES) capture was performed by using Agilent SureSelect Exon Capture Kit, and sequencing was performed with a high-throughput sequencer (Illumina) at a depth of 100×. The original sequencing data were processed by Illumina base-calling Software 1.7 and then compared the data with the human genome DNA reference sequence (NCBI build 37.1) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Single nucleotide variants (SNV), insertion and deletion variants (Indel) were analyzed by SOAP software (http://soap.genomics.org.cn) and BWA software (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/), to obtain all the variants occurring in the DNA sequences in the samples. Then filtered out the high-frequency variant sites with Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) > 1% in the database (db135), and filtered out the variants that do not affect the structure and function of proteins. After step-by-step filtering, the homozygous variants shared by all patients in the family were screened to identify candidate pathogenic variations. Sanger sequencing was used for candidate pathogenic variants to exclude false positives, and further co-segregation of genotypes and phenotypes was validated among normal family members. At the same time, identify homozygous regions in the genome and construct a haplotype network for the proband, analyze the linkage disequilibrium within the haplotypes, and assess the association between haplotypes and specific phenotypes. The determination of the size of homozygous regions is based on the calculation of B-allele frequency (BAF), while haplotype analysis and the analysis of the size of homozygous regions are based on software such as SEE GENE Rare Variant Genetic Analysis Software, SEE GENE Ophthalmic Functional Genomics Analysis Platform, SEE GENE Ophthalmic Disease Genetic Pathogene Platform, and SEE GENE Genetic Variation Statistical Test Software.

Fluorescence quantitative PCR

Fluorescence quantitative PCR was performed to verify the detected copy number variant. Genomic DNA (gDNA) from the peripheral blood of family members was extracted using a blood genomic DNA extraction kit (Beijing Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.). Primers were designed for the gene under investigation. The qPCR reaction system was prepared according to the NovoStart® SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus kit. The 20-µL system contained 10 µL of 2×NovoStart® SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primers, an equal volume of 1 µL of gDNA (10 ng), and 8 µL of water. An initial denaturation (95 °C for 1 min) followed by 40-cycle amplification (95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s) program was performed on a Roche Light Cycler II 480 real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument, with 3 replicates per reaction. The copy numbers of genes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method, normalized by the Ct values of the internal reference genes, and healthy individuals served as reference. For autosomes, a relative copy number around 2 indicates a normal sample, while a relative copy number value around 1 indicates a sample with a 1 copy number deletion.

Pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) established Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence variants in 2015, which were used to evaluate the pathogenicity of novel variations for genetic variation. MAF < 0.005 was used as the criteria to exclude benign variants by reference to the databases for East Asian populations Allele frequencies available with 1000 Genomes Project (1000G, http://browser.1000genomes.org) and Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Polyphen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2, SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org), REVEL (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5065685/), CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/score) and Mutation Taster (http://mutationtaster.org/) were used for pathogenicity prediction. Measurements of the conservation of gene sequences across species in evolution have been made using websites like GERP++ (https://bio.tools/gerp). Variants were classified as uncertain clinical significance when at least 1 of 4 predictions had a benign outcome or when there was insufficient evidence of pathogenicity. When all predictions turned out to be accurate, variations were categorized as potentially pathogenic when used in conjunction with further data. Pathogenic variants were defined as frameshift, nonsense, and variants with experimental proof of causing loss of protein function. For the conservativeness study of variant loci, the online analysis tool Multalin (http://sacs.ucsf.edu/cgi-bin/multalin.py) was employed. Interpretation rules of copy number variants (CNV) referred to the 2019 Edition of the ACMG Guidelines for Interpretation and Reporting of Copy Number variants38. Alphafoldwas used to construct the normal protein structure, and Pymol 2.3 software was used to make a visualized analysis of the mutant protein.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the [Banklt] repository (BankIt (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/WebSub/) ID: PQ038085, PQ038086, PQ038087, PQ045748, PQ045749, PQ045750.

References

Scholl, H. P. N. et al. Emerging therapies for inherited retinal degeneration. Sci. Transl Med. 8, 368rv6 (2016).

Jespersgaard, C. et al. Molecular genetic analysis using targeted NGS analysis of 677 individuals with retinal dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 9, 1219 (2019).

Sen, P. et al. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in South Indian population aged above 40 years. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 15, 279–281 (2008).

Smith, E. D. et al. Classification of genes: Standardized clinical validity assessment of gene-disease associations aids diagnostic exome analysis and reclassifications. Hum. Mutat. 38, 600–608 (2017).

Strande, N. T. et al. Evaluating the clinical validity of gene-disease associations: An evidence-based framework developed by the clinical genome resource. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 895–906 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals novel USH2A mutation associated with diverse disease phenotypes: Implications for clinical and molecular diagnosis. PLoS One. 9, e105439 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Novel USH2A compound heterozygous mutation cause RP/USH2 in a Chinese family. Mol. Vis. 16, 454–461 (2010).

Dai, H. et al. Identification of five novel mutations in the long isoform of the USH2A gene in Chinese families with Usher syndrome type II. Mol. Vis. 14, 2067–2075 (2008).

Zhang, X. et al. Comprehensive screening of CYP4V2 in a cohort of Chinese patients with Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Mol. Vis. 24, 700–711 (2018).

Liang, J. et al. Identification of novel PROM1 mutations responsible for autosomal recessive maculopathy with rod-cone dystrophy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 257, 619–628 (2019).

Dan, H., Huang, X., Xing, Y. & Shen, Y. Application of targeted panel sequencing and whole exome sequencing for 76 Chinese families with retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8, e1131 (2020).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Genetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J. Med. Genet. 56, 662–670 (2019).

Sun, Z. et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of the ABCA4 gene associated retinal dystrophy in a large Chinese cohort. Exp. Eye Res. 202, 108389 (2021).

Application of Whole Exome and Targeted Panel. Sequencing in the clinical molecular diagnosis of 319 Chinese families with inherited retinal dystrophy and comparison Study - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30029497/

Sahoo, S. A., Zaidi, R. A., Anagol, S. & Mathieson, I. Long runs of homozygosity are correlated with marriage preferences across Global Population samples. Hum. Biol. 93, 201–216 (2021).

Ito, M. et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia caused by homozygous DNAAF1 mutations resulting from a consanguineous marriage: A case report from Japan. Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.3263-23 (2024).

Khayat, A. M. et al. Consanguineous marriage and its association with genetic disorders in Saudi Arabia: A review. Cureus 16, e53888 (2024).

Campbell, H. et al. Effects of genome-wide heterozygosity on a range of biomedically relevant human quantitative traits. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 233–241 (2007).

Carlson, L. M. & Vora, N. L. Prenatal diagnosis: Screening and diagnostic tools. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 44, 245–256 (2017).

van Wijk, E. et al. Identification of 51 novel exons of the Usher syndrome type 2A (USH2A) gene that encode multiple conserved functional domains and that are mutated in patients with Usher syndrome type II. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 738–744 (2004).

Hartel, B. P. et al. A combination of two truncating mutations in USH2A causes more severe and progressive hearing impairment in Usher syndrome type IIa. Hear. Res. 339, 60–68 (2016).

Hufnagel, R. B. et al. Tissue-specific genotype-phenotype correlations among USH2A-related disorders in the RUSH2A study. Hum. Mutat. 43, 613–624 (2022).

Yanardag, S., Rhodes, S., Saravanan, T., Guan, T. & Ramamurthy, V. Prominin 1 is crucial for the early development of photoreceptor outer segments. Sci. Rep. 14, 10498 (2024).

Michaelides, M. et al. The PROM1 variant p.R373C causes an autosomal dominant bull’s eye maculopathy associated with rod, rod-cone, and macular dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 4771–4780 (2010).

Ragi, S. D. et al. Compound heterozygous novel frameshift variants in the PROM1 gene result in Leber congenital amaurosis. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 5, a004481 (2019).

Del Pozo-Valero, M. et al. Expanded phenotypic spectrum of retinopathies associated with autosomal recessive and dominant mutations in PROM1. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 207, 204–214 (2019).

Conley, S. M. & Naash, M. I. Gene therapy for PRPH2-associated ocular disease: Challenges and prospects. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, a017376 (2014).

Perea-Romero, I. et al. Genetic landscape of 6089 inherited retinal dystrophies affected cases in Spain and their therapeutic and extended epidemiological implications. Sci. Rep. 11, 1526 (2021).

Wawrocka, A. et al. Novel variants identified with next-generation sequencing in Polish patients with cone-rod dystrophy. Mol. Vis. 24, 326–339 (2018).

Cheng, J. et al. A novel splicing mutation in the PRPH2 gene causes autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa in a Chinese pedigree. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 3776–3780 (2019).

Pigino, G. Intraflagellar transport. Curr. Biol. 31, R530–R536 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Xu, M., Zhang, M., Yang, G. & Li, X. A novel BBS9 mutation identified via whole-exome sequencing in a Chinese family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 4514967 (2021).

Tang, H. Y., Xie, F., Dai, R. C. & Shi, X. L. Novel homozygous protein-truncating mutation of BBS9 identified in a Chinese consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 9, e1731 (2021).

Suárez-González, J., Seidel, V., Andrés-Zayas, C., Izquierdo, E. & Buño, I. Novel biallelic variant in BBS9 causative of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: expanding the spectrum of disease-causing genetic alterations. BMC Med. Genomics. 14, 91 (2021).

Schneider, N. et al. Inherited retinal diseases: linking genes, disease-causing variants, and relevant therapeutic modalities. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 89, 101029 (2022).

Zampaglione, E. et al. Copy-number variation contributes 9% of pathogenicity in the inherited retinal degenerations. Genet. Med. 22, 1079–1087 (2020).

World Health Organization. World Report on Vision 180 (Geneva, 2019).

Riggs, E. R. et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22, 245–257 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and their family members for their participation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82260206), National Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2024AAC03536), the training project of the scientific innovation commanding talented person in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2020GKLRLX13), Major achievement transformation project of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2022CJE09011), the key research development project of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2024BEG02017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F. and W.N. R. wrote the main manuscript, and Z.L. and L.Z.S. collected cases data and followed up patients. W. N.R. and X.L.S. polished the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee on Human Research at People Hospital in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region accepted and examined our work (reference number: 2022-KJCG-006), which adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant or their legal guardians provided their written informed permission before to taking part.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, X., Li, Z., Sha, L. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations for 17 Chinese families with inherited retinal dystrophies due to homozygous variants. Sci Rep 15, 3043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87844-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87844-5