Abstract

Access-based consumption of clothing has garnered attention because of its sustainability potential; however, the profile of a product-service combination that benefits both consumers and the environment has been inconclusive. To characterize these services, this study explored consumer preferences and climate change impact of diverse garment type and service combinations for a clothing rental service. We performed a web-based survey in Japan to analyze consumer preferences and intended behavior for 15 garment types and ten service types in clothing rentals. The survey results were used to characterize the desired clothing rental service using a cluster analysis and to calculate life cycle greenhouse gas emissions when the garment was purchased and rented. The results showed a specific combination of consumer segments, product characteristics, and service types that construct a sustainable clothing rental service; formal dress, dress shirt, and maternity wear were the garment types that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 21% ~ 75% depending on consumer behavior and service implementation. We also demonstrate that implementing services often augments greenhouse gas emissions. This study conveys that renting garments for occasional wear are ideal for both consumers and the environment, and rental service providers need to effectively manage product’s lifetime extension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, the fashion industry has witnessed a surge in clothing rental services, presenting an alternative way to enjoy fashion. Clothing rental services or platforms are categorized as a new business model within the framework of collaborative fashion consumption, sharing economy, product-service system (PSS) or access-based economy that provide short-term access to garments that can be borrowed per piece or via monthly subscription1. In addition to providing users with the opportunity to access diverse styles at a lower cost than the purchasing cost, clothing rental platforms are particularly interesting business models for environmental sustainability. For instance, rental services enable increased resource utilization while serving more demand2. Rental service providers are also incentivized to pursue eco-design and prolong their practical service lives3. Clothing rental services are empowered by information and communication technologies, which have enabled tremendous efficiency gains in terms of coordinating sharing practices among many users. In other words, clothing rental platforms have exceptional potential to counteract the environmental issues of fast fashion, where garments are designed to be worn only a few times4, and have halved the practical service life of garments in the past twenty years5.

To clarify the environmental benefit of clothing rental, studies across the fields examined the conditions when clothing rental outrival ownership through quantitative assessments using life cycle assessment (LCA). The past LCA studies agree that the decisive factors of a non-ownership model to be environmentally advantageous over ownership are related to garment lifetime and usage. For instance, an LCA of a hypothetical clothing library found that environmental impact of garments can only be reduced when the garments’ (in their study, jeans, T-shirts, and dresses) service life is substantially prolonged6. Another factor is the intensification of the garment usage. Garments that are infrequently worn when owned (e.g., occasional wear) have demonstrated environmental advantages through rental because their lifetime wear increases7,8. Other than the garment use, Levanen et al., (2021) showed that a clothing rental with a physical store can result in the greatest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions among the scenarios because of customer’s mobility9; however, major clothing rental services operate on online platforms, where the contribution from the package delivery is limited7,10 Click or tap here to enter text.. Moreover, intensifying the laundry frequency with rentals had a limited impact as long as the laundry avoids dry cleaning10.

While the academic studies are based on predefined scenarios of garment use, Rent the Runway (RTR), a US-based women’s clothing rental company presented an LCA study based on consumer survey. Their LCA incorporated consumers’ expected weartime when owned and when rented for 12 categories of their offering, and found that renting cocktail dresses, skirts and sweaters yields significant environmental savings because their lifetime wear was higher than owning when rented11. The RTR study provides insight in the use patterns of rental garments; however, we are yet to understand the use patterns in relation to consumer perceptions and practices.

Consumer behavior and clothing consumption practices are known to be complicated, as fashion has a symbolic meaning for owners12 and a strong impact on consumer emotions13. In discussions on consumers’ environmental awareness during purchase decisions, studies have discovered that aspects such as fit and style often take precedence in clothing-related decisions14,15. Thus, clothing rental platforms must offer garment pieces that consumers would want to borrow, together with services to facilitate their rental experiences. Previous studies have provided an understanding of consumer drivers and impediments to participating in various access-based business models of fashion products15,16,17 but the type of products and services are often discussed independently from one another. For instance, a winter jackets are likely to fulfill consumers’ needs for a new look without acquiring more garments that are only needed for a short time15; however, the service types that facilitate such service operation is yet to be explored. Likewise, Lang et al., (2020) identified unsatisfied services in online fashion rental as negative evaluation by the users, but the evaluation is disconnected from the garment types12. Access-based offerings are often described as product-service bundles18,19,20, which requires examining consumer preferences for a different combination of products and service types. A conjoint analysis of reuse, refurbishment, and subscription of several home appliances incorporated consumer segmentation, and found significant heterogeneity in consumer preference21. Understanding consumer preferences on what kind of product-service offering would also allow access-based business providers to apply the findings in their practice.

In addition to appealing consumers with a specific combination of garments and services, their clothing consumption patterns need to result in environmental benefits through a clothing rental. As mentioned earlier, consumer behavior is a critical parameter of the life cycle environmental impact of garments and particularly in non-ownership models9,22, but the past quantitative assessments of access-based business models were dominantly based on hypothetical scenarios with limited consumer surveys23,24. Thus, there is a need to not only clarify the relationship between consumer preferences and product-service characteristics but also link them to their behaviors to understand whether the desired product-service type is environmentally viable for that consumer segment.

Furthermore, product-service offerings implement diverse service types22, but their implications on environmental impacts are yet to be clarified. The PSS literature has addressed the challenge of capturing the intangible value of PSS in a functional unit and, more broadly, in evaluating their performance25. PSS often deliver a combination of sub-functions that cannot be separated26, and they can incite rebound effects27. There is a need to quantitatively clarify the environmental implication of services in PSS through connecting service implementation with LCA parameters.

This study aimed to characterize a clothing rental service that meets consumer preferences for garments and services as well as reduces the climate change impact relative to ownership. We contribute to the literature in the following three aspects. Firstly, we clarify consumer preferences for a distinct combination of products and service types of clothing rental services, where we covered 15 garment types and ten service types. Secondly, we present the life cycle GHG emissions of various garments use when they are owned and when they are offered through clothing rental service reflecting consumer segment’s intended behavior from a survey in Japan. Third, we quantitatively demonstrate the environmental consequences of service implementation in clothing rental services. Our analysis involved a web-based consumer survey and cluster analysis, and the GHG emissions were calculated following the LCA guideline.

Results

Clothing rental experience and consumer characteristics

The survey results regarding the experience with clothing rental services appear to reflect the prevalence of clothing rental services in Japan. In the survey, 7% and 34% of the respondents used a clothing rental service with a subscription model and a pay-per-use system, respectively. Of these, 6.8% used both types of clothing rental services. As summarized in Table S5, among the respondents who used a subscription rental service, the three most rented garment types were business attire (e.g., suits and office wears) (60%), formal wear (e.g., formal dress) (57%), and casual wear (52%). For those who experienced pay-per-use services, the top three most rented garment types were formal wear (51%), sportswear (40%), and kimonos and yukata (34%). The results reflect the current market offering, where a subscription model focuses on garments for daily use and pay-per-use is common for occasional wear.

When the respondents’ interest in using clothing rental services were asked, 33% of the respondents were not interested in renting any type of clothing. Among those with no interest in clothing rental, male (67%), especially those in their 30 s (18%) were the dominant groups (Table S6). The percentage of female respondents with no interest in rental clothing increased with age.

Statistical analysis on the consumer characteristics by their desired garment type for rentals suggested that specific consumer characteristics exist in renting each garment type. For example, as Table S7 shows, respondents interested in renting sportswear deem functionality to be important, and those interested in renting knit wears/sweaters deem design to be unimportant while durability is important. Skirt was a garment type with no statistically significant attribute. Additionally, the respondents who had no interest in renting any clothing were characterized by deeming many of the attributes unimportant. They may have low interest in clothing in general.

Garment types favored for rentals

The clothing types that were desirable and undesirable for rentals showed a clear split in preferences. As Fig. 1 shows, coats, suits, dresses, and jackets were frequently selected as desirable rentals. However, we observed a clear disapproval of renting T-shirts/tops (n = 681). The three most frequently chosen garment types that were disapproved for rental after T-shirts/tops were sportswear, leggings/jeans, and short pants. The garment types desired for rental represent a group of garments that are less frequently worn throughout the year, and the undesired ones are basic items that are in closer contact with the skin, which is consistent with previous findings28.

Consumer perceptions of garment types desired for rental were further quantitatively examined in terms of several variables such as expected purchase price, lifetime, and desired rental period, as shown in Table 1. Cardigans, legging pants/jeans, and shorts were omitted from the table because there were fewer than ten responses for these garment types. When the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed on each variable among the garment types, every variable showed that their distributions were nonidentical at 0.01 significance level. In other words, variables such as useful lifetime and expected rental cost varied statistically among the garment types. Several observations were made regarding the purchased and rented garments. The expected rental costs were lower than the expected purchase price, which shows the economic advantage consumers expect from rental services. This result is consistent with past studies in Germany17 and the UK29, where the poorly perceived price-performance ratio of fashion rental hinder clothing rental’s success. As fast fashion continues to dominate the fashion market in these regions, clothing rental appears to be selected when they are price-competitive with purchasing options. The lifetime wear was greater when rented with all garment types except knit wear / sweaters and coats. These garment types are winter clothing, which limits their wearable season.

Linking product characteristics with service types for a clothing rental service

We produced a cross-tabulation of the product characteristics and service types of garments desirable for rent from the survey to represent which service type is more attractive for each of the product characteristic (Table S8). With respect to the product characteristics, “High-priced,” “Occasional use,” and “Seasonal use” were the three most frequently selected product characteristics; clothing with these characteristics had a greater propensity to be rented. By contrast, “Less concern for hygiene” and “Planned use” were the two least selected product characteristics. These results align with past studies on prominent concerns regarding contamination in clothing rental services (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2015). Disapproving “Planned use” contravenes Horton and Zeckhauser (2016)’s account, in which products whose usage can be planned in advance is favorable for access-based consumption30.

In terms of the service types as observed in Table S8, “Free laundry” and “Size that fits” were the two most frequently selected service types for all product characteristics. The least selected service type was “Long rental period” for most of the product characteristics, which aligns with past findings that consumer attitudes were more positive toward short-term use of access-based PSS than that of long-term use31,32. Moreover, several product characteristic-specific selections of service types were observed. Products with “Occasional use” product characteristic were less likely to favor “Monthly subscription,” “New garment” and “Long rental period” relative to other service types. This observation implies that renting garments that are used occasionally is less likely to require a new garment and that short-term use and payment systems are preferred.

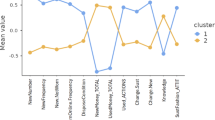

Garment clusters based on product characteristics and service types

The product characteristics and service types were further analyzed by associating them with a specific garment type. Cluster analysis of desirable-for-rental garments excluded cardigans, leggings, pants/jeans, and shorts because they represented less than 1% of the total responses. The clustering results from Table S9 and S10 were combined to illustrate that distinct product-service bundles are desired for each garment type. For instance, Table 2 shows that skirts have the product characteristics of “Less troublesome to launder” and “Less concern for hygiene,” and service types such as “Carrying favorite brands” and “Styling service” are desired in the rental service. Formal dresses and suits, jackets, and coats were the only two groups of garment types with a common combination of product characteristics and service types. The results imply that each garment type has unique motivations for renting, as described by the product characteristics and service types.

Comparative GHG emissions of purchased to rental garments

When the GHG emissions of purchased and rented garments were compared, the GHG emissions per piece were greater for rented garments than for purchased garments for all garment types except knit wear/sweaters, and ten garment types had smaller GHG emissions per wear when rented over purchased. As Figure S3 shows, the GHG emissions per piece of rented garment were greater than those of purchased garments because of repeated laundry from intensifying its use and delivery service. Knit wear/sweaters had a greater GHG emissions per piece because the lifetime wear when rented was less than half of that when purchased. For garments with a fewer lifetime wear when rented than when purchased, such as coats (Figure S3), the increase in GHG emissions when rented was limited. When the unit is expressed in terms of per wear, the influence of the lifetime wears becomes apparent. As shown in Fig. 2, ten garment types had a smaller GHG emissions per wear when rented than when purchased. The largest GHG emission reduction between purchase and rental was observed with formal dress, where the rental case resulted in an 84.2% lower value than that of purchase. According to the survey results, the main reason for this is the tremendous increase in the average lifetime wear (12 times when purchased versus 117 times when rented). For the same reason, the lifetime wear of purchased and rented sportswear was 227 and 297 times, respectively, resulting in a 10.8% reduction in GHG emissions from purchased to rented.

The three garments that resulted in greater GHG emissions per wear when rented than when purchased were seasonal garments: jackets (+ 3.8%), knit wear/sweaters (+ 112%), and coats (+ 214%; Fig. 2). Among them, knit wear/sweaters and coats had much smaller lifetime wear when rented, resulting in a significant increase in GHG emissions. The reason for the small amount of lifetime wear is partly due to our parameter settings for the lifetime. The lifetime of rental garments was set to two years, which means that winter garments were rented for approximately six months. Jackets were worn for three seasons in a year, and the lifetime wear of the rented case was eight times greater than that of the purchased case; however, the GHG emissions of rental were greater than those of the purchased case. This difference arises from industrial laundry and transportation, which augment the GHG emissions from rental garments.

Consequences of rental services

When the influence of the nine service types on the GHG emissions of rental services was examined, the GHG emissions with service consequences were greater than those without service consequences for all garment types. In Fig. 3, some data is shown in a range with “Max–Min with service consequences” because these garments favored “Pay-per-use” or “Monthly subscription,” which had a range of weartime. We found that implementing services generally increases GHG emissions by demanding larger inventories and reducing lifetime wear. Specifically, implementing service consequences exacerbates GHG emissions for suits, knit-wear/sweaters, jackets, coats, skirts, casual dresses, and sportswear. Survey respondents favored several service types that required increased inventories (i.e., diverse style options), which led to increase the GHG emissions.

The three garments that presented lower GHG emissions than those purchased, even with service consequences, were formal dresses, dress shirts, and maternity wear. In other words, these three garment types have the greatest potential to fulfill consumer needs and remain environmentally advantageous when rented. Table 3 summarizes the analysis results for the three garments. Each garment type presented a distinct combination of product characteristics, service types, and consumer segments with an affinity for renting garments.

Discussion and conclusion

Our work is the first to examine 15 garment types and ten service types for access-based consumption, which attempts to unify the understanding of a clothing rental service that meets consumer demands and environmental benefits. The conclusions can be summarized into the following three contributions. Firstly, as Table 3 summarized, we identified a specific combination of consumer segments, product characteristics, and service types that compose a sustainable clothing rental service. Secondly, we showed that formal dress, dress shirt, and maternity wear would reduce GHG emissions by 21% ~ 75% through renting to the target consumer segment relative to ownership. Thirdly, we demonstrated in Fig. 3 that implementing services generally augments GHG emissions in rental services. We now discuss the theoretical and practical implication of our findings and examine limitations.

This study’s first contribution presents an extensive exploration of the possible combination of consumer segments, product characteristics, and service types that construct a sustainable clothing rental service. Theoretically, this study resembles a marketing approach in examining products as a bundle of attributes, where marketers map the attributes in “product space” to understand which bundle effectively matches particular consumer desires33. In this context, we attempted to map attributes in “product-service space.” Several studies have examined two or three products from distinct categories in a single analysis22,34,35, such as bicycles and clothing35. While these studies presented the propensity for certain characteristics to be successful in PSS, limited findings could be applied to a service design and its assessment because product attributes need to be specified for consumers to imagine their use, and for quantitative assessment to be performed. By designating a product category, we demonstrate that distinct garment types are favored for renting different product characteristics. Table 2 exemplifies that the reasons and consumer segments that favored maternity wear were distinct from those for formal wear. Motivation for fashion rentals have been reported to be utilitarian in nature1 but this motivation appeared to be the case with only a dress shirt in this study; indeed, clothing is not generalizable. The product-specific analysis allowed us to understand the characteristics of products and those beyond the functional needs that they fulfill for rental services.

The sustainable clothing rental service characterized in this study is also at the resolution necessary for practical implication. Our results suggest that renting garments for occasional wear are ideal for both consumers and the environment. Recent trends in clothing rental services offer casual workwear36 and several fast fashion brands have entered the rental market37. Our study conveys that simply offering casual wear for rent requires a reconsideration of environmental sustainability. Another contribution to service providers is the clustering of garment types with service types; specific service types that are favored for a garment type or garment cluster were identified. We showed that “Free laundry” and “Size that fits” were universally favored services for all product characteristics, which align with past studies that functional and economic values increase attitudes leading to adopting clothing rentals38, and quality and sizing being the most common barriers39. The low popularity of “Carrying favorite brands” partly resonates with past findings that fashion rentals focus on functional benefits rather than more hedonistic one35. We also showed that skirt was the only garment that favored “Styling service,” and “Size that fits” was more important for sportswear, formal dress, and suits relative to other garment types (Table 2). The garment and service type clusters are also tied to specific consumer segment that are likely to favor service use and enable environmental sustainability. Clothing rental service providers can benefit from leveraging the expected consumer characteristics when developing their services.

The second contribution is the inclusive quantitative GHG emission assessment of clothing rentals; it showed that only three garment types – formal dress, dress shirt, and maternity wear – are likely to have a smaller GHG emissions per wear relative to ownership, when consumer’s preferences, intended behavior, and service implementation are reflected in the calculation. Unlike past LCA studies of collaborative fashion consumptions used predefined scenarios6,7,9,10, we integrated consumers’ preferences and intended behavior of clothing use, which indicates more accurate accounting of environmental potential of clothing rentals. Our results are in partial agreement with the RTR study, where they reported cocktail dresses, skirts and sweaters brought environmental benefit through renting but jeans/pants did not11. We presented contrasting results on sweaters, where the GHG was estimated to increase by 112% when rented compared to owning. The RTR study collected data in the US with their customers, who are dominantly females; this difference in the sample population is one potential factor for the contrasting results. Our study inform rental service providers that garment type and their expected lifetime wear by the target customers must be examined for environmental sustainability.

The third contribution lies in demonstration of a unique example of the environmental impacts of service implementation of PSS. Several studies have warned about the rebound effects of service activities because service provision can augment resource consumption22,23,25. We quantitatively demonstrated that implementing services favored by consumers for each garment type is likely to exacerbates the GHG emissions. Although fashion rentals are expected to promote a longer life cycle and efficient use of resources3, we showed that validity of the claim depends on service implementation and how consumers use rental services. One pattern of GHG augmentation happened with service types that imply increasing inventories, leading to a decrease in the lifetime wear of garments. Rental service providers need to be aware of the environmental consequences of service implementation, as we showed a tendency to exacerbate the GHG emissions, and effectively manage lifetime extension.

This study has several limitations that provide directions for future research. First, our survey results represent consumer intentions in Japan, where attitude-behavior gap and geographical influence certainly exists. A global wardrobe survey reported that the average lifetime wear of a coat and t-shirt was 257 and 151, respectively39. These values are lower than those of our survey results, where many factors such as consumer practices, climate, and ultra-fast fashion prevalence could influence the lifetime wear. Most studies on collaborative fashion are performed in North American and European countries40; more comprehensive cross-cultural studies should be performed to scrutinize the variability in consumer practice across the globe. Another uncertainty in the survey was that simulating the intended use of a clothing rental service would be challenging for those who had never used it, and those who have little interest in clothing rentals. Less than 40% of the respondents used clothing rental services, and 33% of the respondents were not interested in using the service. Because most of the respondents who has experience in clothing rental services used pay-per-use models, the results have a strong bias that represent a pay-per-use model than a subscription model. This bias may explain the consumer preferences for renting clothing with “occasional wear” characteristic. Our results are consistent with the current market in other parts of the world, where clothing rentals remain niche12,16,18,29. There is a need for more studies to chart behaviors of current and past customers of clothing rental services to clarify the attitude-bahavior gap in clothing rental.

This research also faces the common challenges in applying LCA methodology to PSS. We employed two reference flows to understand how each garment performed in clothing rentals. The results have implications for service providers and consumers in deciding whether to rent a specific garment. However, the study is limited to understanding the impact of rental on clothing consumption at the individual or societal level. Examples of alternative functional units for clothing rental services include the absolute consumption by individuals and households such as “the one year of various clothes of one consumer”41. Although collecting reliable data on personal clothing consumption poses tremendous challenges, it is important to assess PSS using multiple functional units. Another uncertainty in the LCA lies in the system boundary, as we omitted the inventory and backyard management necessary to operate the clothing rental service. Because garment production is the greatest contributor to the life cycle GHG emissions of garments, future assessments should examine the impact of inventories and garment management on lifetime extension.

Another limitation of our quantitative results is the scenario setting. The transportation, laundry method, and aforementioned inventory volumes were fixed values set by the authors. The laundry method assumed machine washing in cold water for both domestic and industrial, which is a common practice in Japan. The contribution from laundry would be altered for different temperature setting and wash cycle length42. The garment fiber type was limited to polyester; thus, our quantitative conclusion is valid provided that the environmental impacts of the garment fiber types are comparable. Fiber composition is a critical design parameter of a garment that influences garment weight as well as the method and frequency of laundry. Although each fiber type can be applied to all garment designs, there is a tendency for a specific fiber composition to be selected for each garment type. In addition, this study assumed the garments to be the same for both renting and owning, when specific fiber types or design could be applied to enhance the durability of rental garments. When the durability of a rental garment is enhanced more than a purchased garment, the embodied GHG emissions of the garments, use patterns, and garment care would change, and it is yet to be examined. Analyzing garment designs between garments for purchase and rental is an important research topic.

Methods

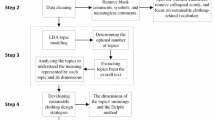

The method consisted of garment and service selection, consumer analysis based on a web survey, and environmental impact assessment using LCA. First, garments, product characteristics, and service types were selected based on a literature review. Next, we performed a consumer analysis based on a web survey to characterize the relationship between consumer segments and their preferences towards product-service bundles which provided data on the expected use patterns of owned and rental clothing. The consumer analysis results provided parametric values for performing an LCA on fashion rentals of the garments examined. LCA was also performed with service consequences to examine the impact of consumer needs on services.

List of garments, product characteristics, and service types

We selected 15 garment types, eight product characteristics, and ten service types for examination for this study. The garment types were selected from a garment category43 and refined by reviewing the types offered by fashion rental services: Skirt, casual dress/all-in-one, sportswear, maternity wear, formal dress, suits, knit wear/sweater, T-shirts/tops, shirts/blouses, formal dress, dress shirts, jackets, coats, cardigan, and shorts. The product characteristics and service types of clothing rental services were selected through a literature review and media accounts of various rental services. As shown in Table 4, each product characteristic and service type correspond to one or more product or service types in the literature. Due to the intricate nature of product-service bundle, some product characteristics such as “life cycle cost” applies to express both product characteristics and service types.

Consumer analysis

Survey design

The survey consisted of four sections illustrated in Figure S1. The full questionnaire is shown in Table S1. Section A asked for basic demographic information. Section B identified the consumer segments by quantifying the importance of specific apparel attributes, such as design, brand, and functionality, in clothing purchase decisions.

The following two sections asked about consumer preferences for clothing rental services: Respondents were first asked to select one or two garments that they would (C1) and would not (D1) be interested in renting from the list of fifteen garment types. Respondents were allowed to skip this section if they had no garments that they wanted to rent. For the garments preferred for rental, the survey had four subcategories: expected consumer behavior when the garment was purchased, reason for their preferences for rental, preferred service when renting the garment, and expected consumer behavior when renting the selected garment type. The second subcategory asked about the reasons why they would (C2) and/or would not (D2) be interested in renting, and respondents selected the reason from a list of product characteristics. The third subcategory asked about the types of services (Table 4) that the respondents preferred if they were to rent the selected garment.

The survey was conducted by a marketing research company in September 2021. The target respondents were residents of Japan, and the respondent strata were fixed with five age groups (20 s, 30 s, 40 s, 50 s, and 60 s) and two sexes respectively. A minimum of 100 samples were collected from each stratum. The resulting responses consisted of 1041 effective samples after filtering eight unreliable responses.

Survey analysis

The survey analysis aimed to identify a combination of consumer segments, product characteristics, and service types for renting each garment type. First, we performed a cluster analysis of the product and service characteristics responses using the k-means algorithm. Clustering was conducted for clothes that the respondents were interested in renting. Clustering results were interpreted using a standard score, defined as:

where \(\overline{x }\) and \(s\) denote the sample mean and standard deviation, respectively. \({x}_{i}\) denotes the mean value of the ith cluster. The standard score represents the degree to which a cluster’s product and service characteristics differ significantly from the overall mean. Based on the standard score, we identified a garment group that desired a specific product-service combination.

Subsequently, statistical tests were applied to segment the respondents based on their perceptions of fashion consumption. We examined the level of importance of apparel attributes and responses to the garments preferred by renters. Table 1 lists the samples used for the hypothesis tests.

Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test because the Likert scale data were ordinal data. Statistical differences in the median \(m\) of the level of importance for the respondents who desired to rent a specific garment (group r) and the rest of the respondents (group s) were tested, where the difference with p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 were considered significant.

Life cycle assessment

We calculated the life-cycle GHG emissions of garments when purchased and rented using survey results and LCA according to ISO 14,040/14,044:200650. Additionally, we analyzed the environmental consequences of the desired services in clothing rental by varying the parameters linked to the services.

The goal of this LCA was to comparatively assess the environmental impact of garments when purchased and rented, while reflecting consumer preferences for products and services, and their expected behaviors. The functional unit is the provision of garments to be worn by consumers in Japan, and two reference flows are used: garments and wear. Analyzing the system with “one garment [per piece]” demonstrates a product-level perspective, which clarifies the contributions from rental service operations. We also used “one (average) wear [per wear]” to examine the influence of change in use frequency and service life of each garment type by providing them in a rental service6,9. We selected GHG emissions as an environmental impact indicator based on the accessibility to quality data and their importance to climate change51. Geographic specificity was set for consumption in Japan, where the major raw materials are imported, and other stages occur in Japan.

We employed our clothing LCA model10 to compute the GHG emissions of diverse garments under various life cycle scenario parameters. The clothing LCA model uses several design parameters to define the life cycle stages of a garment. Figure S2 illustrates the system boundary of the LCA model. The production stage takes garment type (e.g., skirt, pants), material compositions, and season (e.g., all-year or winter) as input parameters. The consumption stage considers lifetime wear, laundry frequency, and laundry type as parameters. Please refer to Amasawa et al. (2023) for the list life cycle inventories used from a Japanese database52 in the clothing LCA model.

Several LCA parameters were set as constants between the purchased and rented garments to closely examine consumer behavior. The fiber content of the garments was assumed to be 100% polyester because polyester is a dominant fiber type worldwide, as are garments in fashion rental services in Japan based on practitioner interviews. Gasoline-powered truck delivery is assumed for both purchased and rented garments. End-of-life was set to be incineration because most disposed garments in Japan are incinerated53. The laundry method assumed the common practice in Japan, machine wash in cold water, regardless of whether garments were purchased or rented. Coats and sweaters may be dry-cleaned, but the laundry method choice depends not only on clothing materials but also multiple factors such as economic, accessibility, cultural, and personal factors54. The interviews with fashion rental providers also indicated that rental garments were laundered by industrial aqueous washing. Other garment care practices were omitted in this study. Consumer behavior toward the purchased and rented garments was determined based on the survey responses. The calculation of the lifetime wear of purchased and rental garments is described in the Supporting Information.

Laundry frequency was set based on the seasonality of the garment type and whether the garment was purchased or rented. For purchased garments, we assumed that summer garments (e.g., T-shirt and sportswear) were washed with every wear, winter garments were washed three times, and others were washed once after two wears. Coats and jackets were assumed to have been washed every season. The wear frequency was estimated based on the literature7,55. The rental garments were assumed to be washed domestically at the same frequency as garments purchased garments during the rental period. In addition, rented garments were assumed to be industrially laundered by rental services when returned. See Table S2 for the set values.

The transportation stage included the supply chain in the garment manufacturing and transport between a retail store or rental service, and the consumer. The total supply chain distance was considered to be 400 km, with a 4 t gasoline-powered truck56. Based on interviews with a fashion rental provider, the distance between a retail store and consumers was arbitrarily set at 10 km, and that from a rental service was set at 60 km. Transport between a retail store or rental service and a consumer was assumed to occur through truck delivery.

To analyze the environmental implications of service introduction in clothing rental, we linked service types with the LCA scenario parameters, as shown in Table S3. In selecting service types to analyze the consequences for each garment type, we examined the service types that had a standard score above 0.5, and those for which 40% of the respondents answered that the service type was favored while renting garments. The styling service was omitted from the analysis because its relevance to the LCA parameters was unclear. The values for each scenario variable were set based on a survey of operating fashion rental services and arbitrary assumptions. A list of the service types included for each garment is presented in Table S43.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request. The questionnaire is included in Supporting Information.

References

Mukendi, A. & Henninger, C. E. Exploring the spectrum of fashion rental. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 24, 455–469 (2020).

Pouri, M. J. Eight impacts of the digital sharing economy on resource consumption. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168, 105434 (2021).

Iran, S. & Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption and its environmental effects. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 21, 468–482 (2017).

Sjoman, A. Zara: IT for Fast Fashion. Harvard Business School Cases (2004).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future (2017).

Zamani, B., Sandin, G. & Peters, G. M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: Can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion?. J. Clean Prod. 162, 1368–1375 (2017).

Piontek, F. M., Amasawa, E. & Kimita, K. Environmental implication of casual wear rental services: Case of Japan and Germany. Proced. CIRP 90, 724–729 (2020).

Johnson, E. & Plepys, A. Product-service systems and sustainability: Analysing the environmental impacts of rental clothing. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13, 1–30 (2021).

Levänen, J., Uusitalo, V., Härri, A., Kareinen, E. & Linnanen, L. Innovative recycling or extended use? Comparing the global warming potential of different ownership and end-of-life scenarios for textiles. Environ. Res. Lett. 16(5), 054069 (2021).

Amasawa, E., Brydges, T., Henninger, C. E. & Kimita, K. Can rental platforms contribute to more sustainable fashion consumption? Evidence from a mixed-method study. Clean. Responsib. Consum. 8, 100103 (2023).

Rent the Runway. RTR commissions first comprehensive study of clothing rental model’s impact; finds renting yields net environmental yields net environmental savings compared to buying clothes. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rtr-commissions-first-comprehensive-study-clothing-rental-/ (2021).

Lang, C., Li, M. & Zhao, L. Understanding consumers’ online fashion renting experiences: A text-mining approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 21, 132–144 (2020).

Niinimäki, K. Eco-Clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustain. Dev. 18, 150–162 (2010).

Bly, S., Gwozdz, W. & Reisch, L. A. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 39, 2 (2015).

Armstrong, C. M., Niinimäki, K., Kujala, S., Karell, E. & Lang, C. Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: Exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J. Clean Prod. 97, 30–39 (2015).

Lang, C. Perceived risks and enjoyment of access-based consumption: identifying barriers and motivations to fashion renting. Fash. Text. 5, 23 (2018).

Bodenheimer, M., Schuler, J. & Wilkening, T. Drivers and barriers to fashion rental for everyday garments: An empirical analysis of a former fashion-rental company. Sustain.: Sci. Pract. Policy 18, 344–356 (2022).

Khitous, F., Urbinati, A. & Verleye, K. Product-Service Systems: A customer engagement perspective in the fashion industry. J. Clean Prod. 336, 130394 (2022).

Reim, W., Parida, V. & Örtqvist, D. Product-Service Systems (PSS) business models and tactics - A systematic literature review. J. Clean Prod. 97, 61–75 (2015).

Gaiardelli, P., Resta, B., Martinez, V., Pinto, R. & Albores, P. A classification model for product-service offerings. J. Clean Prod. 66, 507–519 (2014).

Koide, R., Yamamoto, H., Kimita, K., Nishino, N. & Murakami, S. Circular business cannibalization: A hierarchical bayes conjoint analysis on reuse, refurbishment, and subscription of home appliances. J. Clean Prod. 422, 138580 (2023).

Amasawa, E., Shibata, T., Sugiyama, H. & Hirao, M. Environmental potential of reusing, renting, and sharing consumer products: Systematic analysis approach. J. Clean Prod. 242, 118487 (2020).

Koide, R., Murakami, S. & Nansai, K. Prioritising low-risk and high-potential circular economy strategies for decarbonisation: A meta-analysis on consumer-oriented product-service systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 155, 111858 (2022).

Meshulam, T., Goldberg, S., Ivanova, D. & Makov, T. The sharing economy is not always greener: A review and consolidation of empirical evidence. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 013004 (2024).

Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy – a review. J. Clean Prod. 97, 76–91 (2015).

Kjaer, L. L., Pagoropoulos, A., Schmidt, J. H. & McAloone, T. C. Challenges when evaluating product/service-systems through Life cycle assessment. J. Clean Prod. 120, 95–104 (2016).

Castro, C. G., Trevisan, A. H., Pigosso, D. C. A. & Mascarenhas, J. The rebound effect of circular economy: Definitions, mechanisms and a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 345, 131136 (2022).

Armstrong, C. M., Niinimäki, K., Lang, C. & Kujala, S. A use-oriented clothing economy? Preliminary affirmation for sustainable clothing consumption alternatives. Sustain. Dev. 24, 18–31 (2016).

Herold, P. I. & Prokop, D. Is fast fashion finally out of season? Rental clothing schemes as a sustainable and affordable alternative to fast fashion. Geoforum 146, 103873 (2023).

Horton, J. J. & Zeckhauser, R. J. Owning, using and renting: Some simple economics of the sharing economy. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2746197 (2016).

Edbring, E. G., Lehner, M. & Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean Prod. 123, 5–15 (2016).

Durgee, J. F. & Colarelli O’Connor, G. An exploration into renting as consumption behavior. Psychol. Mark. 12, 89–105 (1995).

Lifset, R. Moving from products to services. J. Ind. Ecol. 4, 1–2 (2000).

Rademaekers, K., Svatilkova, K., Vermeulen, J., Smit, T. & Baroni, L. Environmental Potential of the Collaborative Economy (2018).

Tunn, V. S. C., Van den Hende, E. A., Bocken, N. M. P. & Schoormans, J. P. L. Consumer adoption of access-based product-service systems: The influence of duration of use and type of product. Bus Strateg. Environ. 30, 2796–2813 (2021).

Henninger, C. E., Amasawa, E., Brydges, T. & Piontek, F. M. My wardrobe in the cloud: An international comparison of fashion rental. In Handbook of Research on the Platform Economy and the Evolution of E-Commerce (ed. Ertz, M.) 153–175. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7545-1.ch007. (IGI Global, 2021)

Chua, J. M. The environment and economy are paying the price for fast fashion – but there’s hope VOX https://www.vox.com/2019/9/12/20860620/fast-fashion-zara-hm-forever-21-boohoo-environment-cost (2019).

Baek, E. & Grace Oh, G. E. Diverse values of fashion rental service and contamination concern of consumers. J. Bus Res. 123(165), 175 (2021).

Klepp, I. G., Laitala, K. & Wiedemann, S. Clothing lifespans: What should be measured and how. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12, 1–21 (2020).

Arrigo, E. Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. J. Clean Prod. 325, 129261 (2021).

Piontek, F. M., Rapaport, M. & Müller, M. One year of clothing consumption of a German female consumer. Proced. CIRP 80, 417–421 (2019).

Klint, E., Johansson, L. O. & Peters, G. No stain, no pain–A multidisciplinary review of factors underlying domestic laundering. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 84, 102442 (2022).

Japan Association of Specialists in Textiles and Apparel. Report on Clothing Consumption (in Japanese) (2020).

Tukker, A. Eight types of product-service system: Eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from suspronet. Bus Strateg. Environ. 13, 246–260 (2004).

Camacho-Otero, J., Boks, C. & Pettersen, I. N. User acceptance and adoption of circular offerings in the fashion sector: Insights from user-generated online reviews. J. Clean Prod. 231, 928–939 (2019).

Mont, O., Dalhammar, C. & Jacobsson, N. A new business model for baby prams based on leasing and product remanufacturing. J. Clean Prod. 14, 1509–1518 (2006).

Mont, O. Reducing life-cycle environmental impacts through systems of joint use. Greener Manag. Int. 63, 15P (2004).

Kurisu, K., Ikeuchi, R., Nakatani, J. & Moriguchi, Y. Consumers’ motivations and barriers concerning various sharing services. J. Clean Prod. 308, 127269 (2021).

Lawson, S. J., Gleim, M. R., Perren, R. & Hwang, J. Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. J. Bus Res. 69, 2615–2623 (2016).

ISO. ISO 14040: Environmental management — life cycle assessment — principles and framework. Environ. Manag. 3, 28 (2006).

Niinimäki, K. et al. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth. Environ. 1, 189–200 (2020).

Japan Environmental Management Association for Industry. IDEA (Inventory Database for Environmental Analysis) (2010).

The Japan Research Institute. Ministry of the Environment 2020 Report on Fashion and the Environment (in Japanese) (2021).

Dao, J. F. & Joyner Martinez, C. M. Defining sustainable clothing use: A taxonomy for future research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.13033 (2024).

Moon, D., Amasawa, E. & Hirao, M. Laundry habits in Bangkok: Use patterns of products and services. Sustainability (Switzerland) 11, 4486 (2019).

METI. LCA Report on Textile Products (Clothing) (in Japanese) (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 20K12082 and 23K01982 as well as the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20223R04) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of Japan.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no completing interests.

Ethics declaration

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was acquired from the Research Ethics Committee of School of Engineering at the University of Tokyo.

Consent to participate

Informed Consent of all survey patients were obtained following the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amasawa, E., Kimita, K., Yoshida, T. et al. Exploring different product-service combinations for sustainable clothing rental service based on consumer preferences and climate change impacts. Sci Rep 15, 10555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87893-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87893-w