Abstract

This study assessed patient handover practices and associated factors among inpatient nurses at South Wollo Zone hospitals in Ethiopia (2022). A hospital-based cross-sectional study using a structured questionnaire and observational checklist was conducted with 389 of which 369 of them responded the self-administered questionnaire inpatient nurses. The overall handover practice level was 43.6%. Positive associations were found with technology use and the availability of protocols, while fatigue and intrusions negatively impacted practice. The study highlights the need to improve handover practices through technological enhancements, the development of effective protocols, and improved nurse staffing to mitigate fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing global burden on healthcare systems, driven by rising patient numbers and complex chronic conditions1,2, necessitates a focus on efficient and safe clinical handover practices. Clinical handover is a critical component of the World Health Organization’s patient safety program, and communication failures during this process contribute significantly to adverse patient outcomes3,4.

Globally, millions of hospitalizations occur annually, resulting in a substantial number of adverse events, disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries5,6. Ineffective communication during handover is a well-recognized contributor to patient harm, accounting for a significant percentage of adverse events4,7. Clinical handover involves the transfer of responsibility and accountability for patient care, and its high frequency underscores its importance in healthcare delivery4.

While quality of care is a crucial determinant of health outcomes, improvements in this area receive less attention in many low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa8,9. Studies in Ghana10 have highlighted suboptimal acute care quality linked to factors such as resource availability and communication. Previous research has identified various factors influencing handover practices, including technology11, safety climate, patient family involvement, cultural aspects, staff issues, time constraints, and educational factors3,4.

International initiatives have aimed to standardize clinical handover through structured tools, and technology, but gaps remain in actual practice due to a lack of evidence-based interventions4,12,13. Studies across various regions have shown inconsistent levels of effective handover practice and highlighted factors such as intrusions, distractions, inadequate staffing, time constraints, and communication problems as significant barriers14,15.

This study aims to assess the current practice of patient handover among inpatient nurses and identify the factors affecting it in South Wollo Zone hospitals, in Ethiopia. The study will offer recommendations for reviewing curricula and training methods at educational institutions. For hospital managers and head nurses, the findings will help identify internal and external factors affecting nurses during patient handovers. Understanding these issues will enable nurse managers to better support their staff in fulfilling their professional duties. Additionally, the study will benefit the community and patients by potentially reducing hospital stays, improving treatment outcomes, facilitating early complication identification, and lowering treatment costs.

Literature review

Global data on nursing handover

Globally, an estimated 1.6 million patient handovers occur daily in teaching hospitals, exceeding 300 million in the USA, 40 million in Australia, and 100 million in England16. This highlights the critical role of handover in patient care and the significant communication demands it places on healthcare professionals. A study by the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare found that 37% of handovers were deemed unsuccessful17, emphasizing the need for improvement. Further underscoring this need, an Australian multi-site survey revealed that only 36% of healthcare professionals reported conducting effective handover practices18.

While quality care is crucial for positive health outcomes, particularly for acutely ill patients, initiatives to enhance handover practices receive less attention in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Research in Ghana highlights suboptimal acute care quality linked to resource limitations and communication challenges8,9,19.

Clinical handover is a significant site for communication failures, contributing to 70% of healthcare sentinel events and increasing the risk of adverse patient outcomes20. A concerning statistic is that approximately two-thirds of all adverse events occur in LMICs21, highlighting a critical area for improvement in resource-constrained settings. However, comprehensive data on handover practices specifically within African contexts remains limited.

Four primary handover methods are employed: traditional verbal handover, recorded/taped handover, written handover, and the increasingly utilized digital handover22. A study in Addis Ababa’s Emergency Department (ED) showed that over half (59.2%) of nurses performed proper patient clinical handover23, indicating variability in practice even within a single location.

Mode of handover practice

Verbal handover is frequently the preferred method in inpatient settings due to its provision of immediate, firsthand information24. However, the importance of comprehensive documentation to reduce reliance on verbal handovers and minimize their frequency is acknowledged25,

A survey in Australian metropolitan public hospitals found that 55% of healthcare professionals rated their handover practices as very or extremely effective18. Bedside handovers were considered more effective by 44% of respondents, and patient involvement was linked to increased effectiveness by 46%. The overwhelming majority (99%) recognized the importance of strong communication skills, and 41% linked poor handover to potential adverse events.

In the USA, a study of emergency department nursing handovers revealed that verbal telephone reports were most common (81.48%), while EMR use was at 44.44%, and the Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR) tool was used in only 3.7% of cases26. A Turkish survey showed that most nurses (96%) performed handovers, predominantly at the bedside (91.5%) with the head nurse and the receiving nurse (95.6%), but many (53.1%) did not utilize a structured handover tool27.

Research in South Africa found that all observed handovers in the ED were verbal, often supplemented by written documentation22. A Nigerian study indicated that written and bedside verbal handovers were frequently used, while structured tools and audio recording were rarely or never employed28. The study in Addis Ababa ED showed that most (42.5%) used face-to-face verbal handover, with technology use at 49.2%23.

Factors affecting clinical handover practice

A Canadian study of ED nurse shift handovers revealed that structured tools and technology were rarely used, and patient/family involvement was minimal29. Negative influences included interruptions (89.4%), distractions (96%), triage flow issues, security concerns, and inadequate staffing. Positive factors included sufficient cognitive ability, good colleague relationships, and manageable time pressure; however, high fatigue levels (82.8%) were also reported.

A Czech Republic study identified three categories of handover barriers: person/performance-related (messy reports, illegible handwriting, poor communication), environment/device-related (time constraints, interruptions), and organizational (lack of standardized procedures and training)30. The Turkish study highlighted distractions, communication problems, and conflicts with patients/families as significant barriers27.

An Indonesian study demonstrated a significant relationship between negative attitudes and poor handover performance31, as well as between poor knowledge and poor performance. The Nigerian study emphasized the importance of communication, nurses’ attitudes, ethical considerations, and workload in influencing handover effectiveness28.

The Addis Ababa ED study showed that while most respondents had adequate attention and cognitive capacity, high time stress, low fatigue, and poor relationships were also prevalent23. Environmental factors such as overcrowding, high workload, insufficient staffing, intrusions, and distractions significantly impacted handover practices in the mentioned study. Access to technology, effective communication, and patient/family involvement were identified as positive influences too.

Objectives of the study

General objective

To assess patient handover practice and associated factors among inpatient nurses at South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General Hospitals, Wollo Ethiopia 2022.

Specific objectives

To assess patient handover practice among inpatient nurses at South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General Hospitals from August 1-September 1 2022.

To identify factors associated with patient handover practice among inpatient nurses at South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General Hospitals from August 1-September 1 2022.

Methods and materials

Study area

The study was conducted in South Wollo zone in Amhara regional state, located in the North East direction and 520 km away from Bahir- Dar, and 401 km from Addis- Ababa Ethiopia. Having a total population of 2,518,862 by 2007 censuses, 11.98% of the population was urban inhabitant and the largest ethnic group reported in South Wollo was the Amhara (94.33%). In this zone there are one specialized hospital namely Dessie comprehensive specialized hospital and four general hospitals such as BoruMeda general hospital, Kombolcha general hospital, Akesta general hospital, and Mekaneselam general hospital. A total number of inpatient nurses in those hospitals were 482.

Study design and period

Hospital-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from August 1-September 1 2022.

Population

Source population

All inpatient nurses who were working in South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General Hospitals.

Study population

All inpatient nurses who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and working in the inpatient unit of South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General Hospitals.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All nurses working in the inpatient unit of South Wollo Zone Compressive Specialized and General hospitals and who were present at the time of data collection.

Exclusion criteria

Nurses who were on annual and maternity leave during data collection, and student nurses.

Nurses who were seriously ill during data collection.

Sample size determination

The initial sample size was determined by using single population proportion formula based on the following assumptions: considering confidence interval (CI) 95% and margin of error (d) 0.05 and by taking the P (the level of handover practice) is 59.6% which was taken from the study done at Addis Ababa on factor affecting the practice of patient clinical handover on emergency nurses23.

Then: \(n=\left(\frac{Z\alpha\:}{2}\right)2\frac{\left(P\right)\left(1-P\right)}{d2}\)

Where: n = is the initial sample size, Zα/2 = is standard score value for 95% confidence level for two sides normal distribution = 1.96, = is the proportion of respondents = 0.596, d = is margin of error = 0.05.

\(n = \left(1.96\right)2\frac{\left(0.596\right)\left(0.404\right)}{\left(0.05\right)2}\) = \(\:370\), by adding a 5% non-response rate which was taken from the previous study done in Addis Ababa the final sample size was 389.

Sampling technique and procedure

Proportional allocation was made for study participants in each hospital and simple random sampling method was used to select participant nurses from each hospital (Fig. 1).

Variables of the study

Dependent variable

-

Patients’ handover practice.

Independent variables

-

I.

Socio-demographic characteristics.

Sex, Age, Educational status, and Work experience.

-

II.

Nurse-related factors

Nurses’ attitude, Nurses’ knowledge, Level of interaction between nurses (Relationship), and Fatigue.

-

III.

Patient-related factors

Patient or family participation during handover

-

IV.

Working area factors

Availability of standard handover tool, Support policy or protocol for handover practice, Overcrowding, Workload and staff number, Distractions, and Intrusions.

Operational definitions

-

Good handover practice: who scored above or equal to the mean score of observational checklists23,32,33.

-

Poor handover practice: who scored below the mean score of observational checklists23,32,33.

-

Knowledge level scoring system: high knowledge level who score > 75%, moderate knowledge level ranged from 60 to 75% and low knowledge level who score < 60%34.

-

Good attitude towards handover: nurses who score > 60% of the attitude questions34.

-

Poor attitude towards handover: nurses who score < 60% of the attitude questions34.

-

Inpatient nurses: are nurses who are working at (medical, surgical, pediatric and orthopedic) wards.

-

Fatigue: participants who score above the mean score of fatigue questions23.

-

Use of technology: Participants who use cell phone or computer for patient handover23.

-

Distractions: Distractions are breaks in concentration triggered by competing activities or environmental stimuli that are not related to the task at hand including call bells, alarms from IV pumps and monitors, background noise or chatter, and other29.

-

Intrusions: defined as unexpected encounters initiated by another individual that disrupt the flow of activity and cause activity to halt temporarily including patient family colleagues and other29.

-

Structured handover: That the minimum data set (information content) and conduct of handover be delivered in a structured format35.

Data collection tools and procedure

The data was collected using self-administered structured questionnaires for the socio-demographic, knowledge, attitude and associated factors and an observational checklist for the practice aspect was used by adapting from different kinds of literatures23,34,36. The questions were prepared in the English language based on the study objective focusing on the background information of patient handover practice and it has multiple choice questions and a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = partially agree,4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree. The data was collected by 5 BSc nurses and 2 MSc nurse were supervisors. The data collectors gave a self-administered structured questionnaire for nurses to collect data and they fill the observational checklist used for practice aspects. The data collection tools have seven sections such as socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, educational level, working experience), mode of practice, knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors. Seven (7) questions used for knowledge assessment,”1” scored was given for correct answers and 0 given for other alternative, for attitude part fourteen questions used with Likert scale with five alternatives such strongly disagree, disagree, partially agree, agree and strongly agree then after computing variable it was categorized in to positive attitude and negative attitude based on operational definition. For practical aspect there was seven dichotomous choice questions (yes and no), yes was given” 1” point and no given” 0” point and factor variables had dichotomous options (yes and no)” 1” point was given for yes alternative and” 0” point given for no alternatives finally it was computed and categorized based on the operational definition.

Data quality assurance and management

Data collectors and supervisors were trained for one day before data collection about the purpose of the study, how to approach the study participants, the required ethical conduct and the confidentiality of information to ensure consistency. A pretest was done one week before the actual data collection at Kemisse General Hospital to check the applicability of the questionnaire and to check any unclear ideas. The obtained data was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, clarity and consistency. Cronbach alpha was calculated to check internal consistency of each item, so based on this for knowledge questions it becomes 0.736, for attitude aspect questions it was 0.868 and for practice aspect questions it was 0.768. The questionnaire was checked by experts for its face and content validity.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data was checked for clarity, incompleteness, cleaned, coded and entered into Epi-Data version 4.6 and then exported to SPSS software version 26.0 for data analysis. Percentage and frequency of Socio-demographic profile, patient handover practice was presented using descriptive statistics. Bivariable Logistic regression analysis is used to check for statistically significant association between the primary outcome variable and covariates. Variables found to be significant at the bivariable level, (P < 0.25), were selected and included in multiple logistic regression models. Assumptions were checked with model fitness by Hosmer Lemshow having significances of 0.92 and Multicollinearity tests resulting < 10 VIF and the case wise plot is not produced because no outliers were found. In multiple logistic regression analyses, Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 at a 95% confidence interval and adjusted odd ratio were used to declare significant association.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance and approval were obtained from the Department of Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University with the reference number CMHS/10/14. Then the letter was given to those South Wollo Zone Specialized and General hospitals and a permission letter was obtained from the health care quality offices of the hospitals and delivered to the inpatient unit of each hospital to conduct the study. A letter of consent outlining the main aim and details about the study was prepared in conjunction with the questionnaire. In addition to this, before administering the questionnaire informed consent was obtained from the study participants. To assure anonymity and confidentiality, the name of participants was replaced by codes. The study participants were informed about their rights to refuse to join, answer any question or withdraw at any particular point during the data collection process. The purpose, benefit, and risk of the study were explained to the study participants. All the methods of this study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 369 study participants were participated in the study with 94.85% response rate. Of the total participants, 208 (56.36%) were male with and whose age were ranged from 21 to 56 years with the mean age of 34.78 (SD ± 7.518) years. Regarding to the Educational status, more than two-third of the study participants 286 (77.5%) were BSc holders and half of them 181(49.1%) had less than ten years of experience (Table 1).

Handover practices of nurses

Based on practice of nurses’ patient handover practice observational result analysis, the overall good practice of patient handover practice was 43.6% (161) with (95% CI: 38.3–48.7). More than two-third of participants 277 (75.1%) were not followed logical structure during patient handover. Not only this but also 302 (81.8%) of them not used available documentation continuously. Similarly, 255 (69.1%) of the observation revealed that not enough time was allowed for the hand over. This may be supported with observation result 266 (72.1%) of the study participants showed that priorities for further treatment were not addressed and 272 (73.7%) them relevant information was not selected and communicated clearly (Table 2).

Professional and patient related factors

Based on professional and patient related factors analysis result, 145 (39.5%) of participants have high level of knowledge, 80 (22.5%) of them had moderate knowledge level and 144 (39%) of them had poor knowledge towards patient handover. Regarding attitude aspect two-third of participants 255 (69.1%) had positive attitude and the rest 114 (30.9%) of them had negative attitude towards patient handover. Majority of participants 345 (94.3) were not taking training related to ward nursing. Majority of participants 303 (82.1%) respond that they feel fatigue in working area. Regarding patient involvement 222 (60.2%) of the participants involve patients in the handover practice (Table 3).

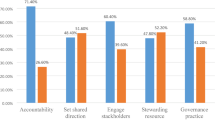

Work area factors towards practice of patient handover

Work area related factors analysis of this study revealed that majority of participants 269 (72.9%) answered that patient handover was not guided by handover tool and half of them 186 (50.4%) said that there was no handover practice implementation protocol. Similarly, 213 (57.7%) the participants responded that the hospital management didn’t support to improve patient handover practice this is also supported by the other variable i.e., half of the participants 188 (50.9%), answered that there is inadequate staff number to manage workload demands and more than half 231 (62.6%) said that there is overcrowded space to do handover in the ward. Only 92 (24.9%) of the participants was use technology in during patient handover. The other variables that affect patient handover practice was presence of intrusion and distraction 249 (67.5%), 95 (25.7) respectively (Table 4).

Factors associated with nurse’s patient handover practice

In the bi-variable analysis, use of technology, training related to ward nursing, fatigue, Colleague’s support, availabilities of guidelines, availability of standard protocol/policy, presence of adequate staff and intrusion, were found to be determinants of patient handover practice.

In the multi-variable binary logistic analysis, Fatigue, use of technology, availability of protocol and intrusions were significantly associated with patients’ handover practice of inpatient nurses.

Availability of protocol was 1.728 times increase patient handover practice compared to unavailability of patient handover protocol (AOR = 1.728 95% CI, 1.093_ 2.731), nurses who use technology 1.668 times more likely to do good patient handover compared to who did not use technology (AOR 1.668 95% CI, 1.02–2.715). Whereas Nurses who have fatigue decrease patient handover by 43.7% as compared to nurses who had no fatigued (AOR = 0.563 95%CI, 0.321–0.989). In addition, presence of intrusion also decreases patient handover practice by 46% as compared to nurses who did not experience intrusion (AOR = 0.54 95% CI, 0.338_ 0.862 (Table 5).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the breadth of nurses’ patient handover practices as well as the variables that affect them among nurses in hospitals found in south Wollo zone of Ethiopia. According to the results, 43.6% (95% CI: 38.3–48.7) of the nurses in the research area showed good patient handover practices. The usage of technology, the accessibility of protocols, fatigue, and the existence of intrusions were among the important factors that were found to be associated with patient handover practices of nurses.

The 43.6% good handover practice proportion is consistent with a 39.3% found in an Indonesian study31. It is, however, less than the results of research conducted by Addis Ababa (59.2%)23, Turkey (96%)27, and the Joint Commission (63%)37. On the other hand, it surpasses a study conducted in Australia that found a proportion of 36%20. These discrepancies could be explained by differences in ecological situations, sample sizes, and research methodologies.

Poor handover practices reveal a communication breakdown between nurses and patients, which has a major effect on patient outcomes and the standard of care. Lack of management assistance was indicated by more than half (57.1%) of survey participants, indicating deficiencies in monitoring, supportive supervision, and follow-up. These results show that there are still inadequacies in hospital communication systems, even with the Ethiopian Ministry of Health’s directives.

Good patient handover practices were found to be significantly and positively predicted by the availability of protocols and the usage of technology. Good patient handovers were 1.67 times more likely to be performed by nurses who used technology than by those who did not. This result is in line with research done in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia23. By removing problems with handwriting readability, lowering energy use, and saving time, technology streamlines the handover process and improves healthcare providers’ access to information of the practice.

In a similar manner, the presence of protocols in the ward greatly enhanced nurses’ patient handover practices; nurses were 1.73 times more likely to perform patient handovers in the presence of protocols. Protocols offer precise instructions on how to carry out handover procedures and deal with accountability concerns. On the other side, intrusions and fatigue were found to be poor indicators of patient handover practice. Compared to nurses who were not fatigue, nurses who were fatigued were 44% less likely to conduct successful handover practices. Fatigue, which is sometimes brought on by a heavy workload, can make it difficult for nurses to carry out their jobs well. This result is consistent with data indicating that a sizable percentage of respondents experienced fatigue and low energy after work, which was made worse by insufficient staffing levels and management support38.

Additionally, handover intrusions had a detrimental effect on the patient handover practice, decreasing it by 46%. These disruptions may occur for a number of reasons, such as pressing requests for patient care or a failure to recognize the need of seamless patient handovers. According to the survey, a sizable portion of participants were aware of how intrusions harm handover practices. These results demonstrate that in order to improve patient handover practices, healthcare organizations must make technological investments and set up explicit procedures. Furthermore, addressing issues like nurse exhaustion and reducing intrusions can greatly enhance patient safety and care quality.

The findings from this study on nurses’ patient handover practices and factors influencing it has several clinical implications. The use of technology in patient handover practices significantly improves communication by reducing errors related to handwriting and ensuring that information is accurately and efficiently transferred; the presence of standardized protocols ensures that all nurses follow a consistent procedure during handovers, which can reduce variability and improve the quality of care, and strategies to manage and distribute workloads more effectively can help reduce nurse fatigue, which is shown to negatively impact handover practices.

Strength of the study

The study gets new findings in the study area so used as spring board for other researchers for the future.

The practice aspect of the study was done by observational checklist.

The study was tried to assess the impact of variables like knowledge, attitude and socio-demographic characteristics on patient handover practice.

Limitation of the study

The practice measuring items was filled by observation, following this; the study participants may be conscious and make ready they to do carefully so it is subjected to bias.

Conclusion and recommendations

Conclusion

Finding of this study showed that the proportion of nurses having good patient handover practice was comparably low, and use of technology, availability of protocol, fatigue and presence of intrusion were the identified significant determinates of nurses’ patient handover practices.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this study the following recommendations are made:

To Hospitals:

-

Should avail technologies (like: cell phone and computer) used for recording of handover patients.

-

Should prepare clinical handover management policy /protocol that managed and facilities clinical hand over policy.

-

Should balance the nurse workforce plan to minimize staff fatigue for a better of handover.

-

The handover management policy or protocol should address how to minimize intrusion during handover.

To Patients:

-

Patients should respect the hospital policy and better to accept health professional suggestion.

To Amhara Regional Health Bureau.

-

Should support hospitals by availing technologies and give orientation about the new technologies.

-

Even if Ethiopian health institution transformation guideline was addressed the clinical hand over practice, for further improvement it is better to follow its implementation.

Data availability

Data will be available from the principal investigator on reasonable request (Anwar Seid, Email: seidanwar22@gmail.com).

References

Kelland, K. Disease X: The 100 days Mission to end Pandemics (Canbury, 2024).

Salomon, J. A. et al. Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global Burden Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859), 2144–2162 (2012).

Merten, H., Van Galen, L. S. & Wagner, C. Safe handover. Bmj;359. (2017).

Desmedt, M., Ulenaers, D., Grosemans, J., Hellings, J. & Bergs, J. Clinical handover and handoff in healthcare: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 33(1), mzaa170 (2021).

Vincent, C. Patient Safety (Wiley, 2011).

Adhikari, N. K. Patient Safety without Borders: Measuring the Global Burden of Adverse Events 798–801 (BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 2013).

Howick, J. et al. How does communication affect patient safety? Protocol for a systematic review and logic model. BMJ open. 14(5), e085312 (2024).

Ameyaw, E. K. et al. Quality of antenatal care in 13 sub-saharan African countries in the SDG era: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 24(1), 303 (2024).

Odhus, C. O., Kapanga, R. R. & Oele, E. Barriers to and enablers of quality improvement in primary health care in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS Global Public. Health. 4(1), e0002756 (2024).

Yakubu, A-S. & Ahadzi, D. Quality of acute coronary syndrome care and in-hospital outcome in a resource-poor setting in Northern Ghana. (2023).

Ratcliffe, H. L. et al. Towards patient-centred care in Ghana: Health system responsiveness, self-rated health and experiential quality in a nationally representative survey. BMJ open. Qual. 9(2), e000886 (2020).

Burgess, A., Van Diggele, C., Roberts, C. & Mellis, C. Teaching clinical handover with ISBAR. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 1–8 (2020).

Zegers, M., Hesselink, G., Geense, W., Vincent, C. & Wollersheim, H. Evidence-based interventions to reduce adverse events in hospitals: A systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ open. 6(9), e012555 (2016).

Gheisari, F., Farzi, S., Tarrahi, M. J. & Momeni-Ghaleghasemi, T. The effect of clinical supervision model on nurses’ self-efficacy and communication skills in the handover process of medical and surgical wards: An experimental study. BMC Nurs. 23(1), 672 (2024).

Altabbaa, G., Beran, T. N., Clark, M. & Paolucci, E. O. Improving clinical reasoning and communication during handover: An intervention study of the BRIEF-C tool. BMJ Open. Qual. 13(2), e002647 (2024).

Eggins, S. & Slade, D. Communication in clinical handover: Improving the safety and quality of the patient experience. J. Public. Health Res. 4(3). (2015).

Alert, S. E. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentin. Event Alert. 58(1), 6 (2017).

Manias, E., Geddes, F., Watson, B., Jones, D. & Della, P. Perspectives of clinical handover processes: A multi-site survey across different health professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 25(1–2), 80–91 (2016).

Atinga, R. A., Kuganab-Lem, R. B., Aziato, L. & Srofenyoh, E. Strengthening quality of acute care through feedback from patients in Ghana. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 5(1), 24–30 (2015).

Pascoe, H., Gill, S. D., Hughes, A. & McCall-White, M. Clinical handover: An audit from Australia. Australasian Med. J. 7(9), 363 (2014).

World Health Organization. Medication without harm (World Health Organization, 2017).

De Lange, S. Improving Patient Handover Practices from Emergency care Practitioners (University of Pretoria, 2016).

Abel, G. & HM, A. W. Assessment of factors affecting patient clinical handover practice of nurses at Emergency department of selected governmental hospitals with trauma center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 56. (2020).

Marutyan, Y. Evaluation of the nursing handoff process from emergency department to In-Patient Unit. (2016).

Sujan, M. & Spurgeon, P. Safety of patient handover in emergency care–results of a qualitative study. Nutr. Care Patient Gastrointest. Disease 359. (2015).

Tobiano, G., Ryan, C., Jenkinson, K., Scott, L. & Marshall, A. P. Handover from the emergency department to inpatient units: A quality improvement study. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 36(4), 339–345 (2021).

Kilic, S. P., Nimet Ovayolu, R., Ozlem Ovayolu, R. & Ozturk, M. H. The approaches and attitudes of nurses on clinical handover. Int. J. Caring Sci. 10(1), 136 (2017).

Alberta David, N., Idang Neji, O. & Jane, E. Nurse handover and its implication on nursing care in the university of Calabar teaching hospital, Calabar, Nigeria. Int. J. Nur Care. 2(3), 1–9 (2018).

Thomson, H. Factors Influencing Quality of Emergency Department Nurse Shift Handover (University of Toronto (Canada), 2015).

Superville, J. G. Standardizing Nurse-to-Nurse Patient Handoffs in a Correctional Healthcare Setting: A Quality Improvement Project to Improve end-of-shift Nurse-to-Nurse Communication Using the SBAR I-5 Handoff Bundle (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2017).

Suryani, L. & Said, F. B. M. Empowering the implementation of patient handover with increasing nurse knowledge and attitude at X General Hospital Indonesia. Age (year). 20(30), 31–40 (2020).

Kumar, P., Jithesh, V., Vij, A. & Gupta, S. K. Need for a hands-on approach to hand-offs: A study of nursing handovers in an Indian Neurosciences Center. Asian J. Neurosurg. 11(1), 54–59 (2016).

Gungor, S., Akcoban, S. & Tosun, B. Evaluation of emergency service nurses’ patient handover and affecting factors: A descriptive study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 61, 101154 (2022).

Mohammed, S. M. & Safan, S. M. Implementing structured model of clinical handover (SHARED): Its influence on nurses’ satisfaction.

Spooner, A. J., Aitken, L. M., Corley, A. & Chaboyer, W. Developing a minimum dataset for nursing team leader handover in the intensive care unit: A focus group study. Australian Crit. Care. 31(1), 47–52 (2018).

Thomson, H., Tourangeau, A., Jeffs, L. & Puts, M. Factors affecting quality of nurse shift handover in the emergency department. J. Adv. Nurs. 74(4), 876–886 (2018).

Ibrahim, J. E. Royal commission into aged care quality and safety: The key clinical issues. Med. J. Aust. 210(10), 439–441 (2019). e1.

de la Fuente, M. V., Castañeda, D. J. P. & Sanz, N. M. The human factor and ergonomics in Patient Safety. Medicina Intensiva (English Edition). (2024).

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks go to the Department of Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, for giving me this chance and support. Next, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my advisor Mr. Wondwossen Yimam (MSc, Assistant Professor), and my co-advisor Mr. Jemal Mohammed (MSc, Lecturer) for their unreserved guidance. I would like to thank the data collectors, supervisors and study participants for their cooperation and participation. Last but not least I would like to thank South Wollo Zone General and Compressive Specialized Hospitals administrators and health care quality officers for giving important information about my research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors equally contributed to conducting this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seid, A., Hussien, W.Y., Bahru, J.M. et al. Patient handover practice of nurses and associated factors in South Wollo Zone Public Hospitals, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 13194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87968-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87968-8