Abstract

For most classifiers, overlapping regions, where various classes are difficult to distinguish, affect the classifier’s overall performance in multi-class imbalanced data more than the imbalance itself. In problem-data space, the overlapped samples share similar characteristics, resulting in a complex boundary, making it difficult to separate the samples of classes from each other, causing performance degradation. The research community agreed upon the relationship of the class overlapping issues with the classifier performance, but how much the classifier is affected is still unanswered. There is also a gap in the literature to demonstrate the different levels of class overlapping in multi-class problems. Accordingly, in this paper, four algorithms are implemented to synthetically generate controlled overlapping samples to be used with multiclass datasets using different schemes to show the worst effect of class overlapping. Experiments involve using different state-of-the-art non-parametric classifiers, support vector machines, k-nearest neighbor, and random forest, to classify these multi-class datasets to validate the class overlapping effect on their learning. The models are used to test the suitability, stability, and versatility of the proposed algorithms for the schemes and to highlight the effect of growing overlapping samples in complex multi-class problems having an imbalanced distribution of data and class overlapping issues. The experimental results using 20 real-world datasets, show the different levels of overlapping data and the effect of each level on the underlying classifiers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

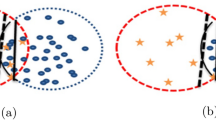

The machine learning algorithms aim to minimize the overall error and are accuracy-driven1. When these algorithms are applied to a problem with a balanced dataset, they show a significant performance. However, in the case of imbalanced data, particularly for multiclass problems, their performance suffers due to imbalanced class distribution where samples of various classes overlap at the boundary region. Figure 12, shows the problem of imbalance, and overlapping. For imbalanced distribution, the dataset is divided into the majority and minority groups. The former group (the majority class) samples outperform the number of the latter group (minority class). This unfair distribution causes the underline classifier inclined towards the majority class while ignoring the minority class samples, even though sometimes these minority class samples carry important information. If a traditional classifier is applied to such imbalanced datasets, it may result in an appropriate classification model3. However, some researchers are of the opinion that imbalanced problems with a small imbalance ratio do not affect severely the classifier performance, and the imbalanced effect could be reduced by using sampling strategies4.

To be more precise, the imbalanced data is not a big problem for the classifier, but the overlapping region created at the boundaries of imbalanced classes is a key issue for the performance degradation of different classifiers5. Often, in real-world datasets6, samples in a particular problem space may share similar attribute values. If they fall at the boundary region of two classes, it would be difficult to clearly define a hyperplane between the classes7. Moreover, the co-occurrence of data imbalance and overlapping has a huge impact on the classifier and reduces its efficiency. In addition, the increase in the number of classes involved in data overlapping makes the classification more challenging8. Hence, the algorithm occasionally fails to properly learn this complex situation and correctly predict the target class for the overlapped sample, thus compromising the overall classification performance and resulting in an impractical classification model.

Classification problems, (a) Sample distribution problem, (b) Overlapping problems in classes, and (c) Imbalance and overlapping issues, adopted from2.

To address the overlapping data problem, the proposed solutions are based on two largely reported approaches:

-

i.

Adaption algorithms: In this approach, the existing algorithm is modified, or a new technique is introduced for handling the complex imbalanced and overlapped data while classifying the multi-class problems. Different algorithm-based approaches like ensemble methods9, one-class learning10, and cost-sensitive-based methods11 are available in the existing literature to improve the classification performance of imbalanced and overlapping data. Fu et al.12 highlight Support Vector Machine (SVM) to be an efficient and generalizable approach in the case of multiple classes, by combining auxiliary algorithm Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)13, optimization techniques14 for parameters, and Two-Step Classification (TSC)15. Czarnecki and Tabor proposed 2eSVM16, a modified SVM to address the overlapping issue. Xiong et al. present a modified Naïve Bayes17, CANB18 for overlapping data, which follow separate learning from overlapped and non-overlapped regions.

-

ii.

Data preprocessing techniques: By adding complimentary features or using data purification techniques to separate the overlapping classes, the original data is modified in the data level method to alleviate/reduce the impact of overlapping data19. To reduce the imbalance effect of the classification model, alternative feature selection strategies are frequently used for sampling procedures. By using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) and its derivatives, some of the prominent sample strategies mentioned in the literature include oversampling, under-sampling, and hybrid sampling20. E. Elyan suggested in21 using an oversampling-based method to eliminate the negative examples of the majority class from the overlapping region. The borderline samples of both the majority and minority groups were included in the sampling-based methodology presented in22. The model may get over-fit or lose some relevant information if the imbalance and overlapping problem is only addressed using data-level procedures23.

Regardless of the significance of both approaches, there is still a gap in showing, how much a classifier’s performance is affected by the degree of overlapping, i.e., methods to measure the degree of overlap are not available for real datasets24. Secondly, most of the literature discusses the default existing overlapping samples and their effect on the underlying classifier, and we did not find any comprehensive study to show the effect of different degrees of synthetic controlled overlapping on classifier performance. To fill this gap, in the current research work, this study contributes in the following areas.

-

We propose four algorithms to introduce a controlled synthetic overlapping into the multi-class imbalanced datasets. These algorithms include Majority-class Overlapping Scheme (MOS), All-class Oversampling Scheme (AOS), Random-class Oversampling Scheme (ROS), and All-class Oversampling Scheme using Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) (AOS-SMOTE).

-

These algorithms allow one to precisely determine samples in overlapping and non-overlapping regions as well as adjust the degree of overlapping between various classes. This thorough categorization of the many sample types in the dataset suggests an entirely new approach to comprehending and assessing the class overlapping concerns in multi-class imbalanced data situations.

-

Algorithms are applied with a different degree of overlap including 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%. The synthetic examples are added to the dataset’s majority class, a randomly chosen class, and all classes in order to test the generality of the suggested techniques.

-

For experiments using different multi-class imbalanced datasets, some well-known classifiers like Random Forest (RF)25, K Nearest Neighbor (KNN)26, and SVM27 are applied to these multi-class datasets to empirically validate the overlapping effect on learning from multi-class imbalanced problems. Synthetic generation of samples through different algorithms enables us to conclude the worse effect of overlapping on the learning of the underlying classifiers over 20 multi-class real datasets.

-

An extensive experiment on different artificial and real datasets is carried out, to provide a solid basis to establish the conclusion about the class overlapping effect on classifier performance via conventional confusion metric in terms of accuracy and precision.

In the preceding sections, related work is given in “Related work” section. “Quantification of class overlapping” section presents the quantification of class overlapping. Proposed oversampling approaches for generating synthetic samples are discussed in “General synthetic samples in multiclass datasets using proposed algorithms” section. “Working mechanism for all schemes” section provides details of the working mechanism of all schemes while results are presented in “Results and discussions” section. Finally, “Conclusions” section concludes this study.

Related work

Classification of imbalanced data in multi-class problems is getting more attention, as their existence in the majority of real-world Applications, like medicine, finance, mechanics, different industries, and automation, while dealing with data mining and big data environments. In the majority of these applications, the data collection based on some objective conditions with the predefined characteristics of data attributes results in an overlapping region among the different class samples. With the increasing degree of class overlapping the underlying classifier also, compromises its overall performance, by misclassifying the samples at the boundary line.

Different studies in the literature agreed upon the assumption that most of the time, the classification error generally focused on the borderline of different classes, which is an exactly overlapped region consisting of the samples of both classes28. Overlapping is the most crucial issue than the data imbalance problem as reported by Denil and Trappendberg29. Garc and his co-authors in30 generate artificial datasets to show the effect of overlapping data on classifier performance using KNN based on the overall imbalance ratio and local imbalance ratio.

Class imbalance and overlapping problems become more challenging for the applications of conventional algorithms as reported by Han Kyu Lee and Seoung in2. While overlapping happens when a borderline region in the data space is made up of similar data for many classes, the class imbalance is the outcome of the imbalance in the class samples, giving rise to the majority and minority class (es). The authors deal with the overlapping zones by dividing them into less overlapped (soft overlapping) and densely overlapped (hard overlapping) regions by proposing the Overlap Sensitive Margin (OSM) classifier. The OSM classifier combines KNN with the Fuzzy SVM (FSVM) to address issues of imbalanced and overlapping classes for multi-class domains. The weight that was previously given to SFVM to remedy the class imbalance issue is essentially different from the misclassification cost that the OSM classifier applies to FSVM. The KNN technique determines the level of sample overlap in the dataset. The trained OSM classifier then uses a hyperplane to divide the overlapping area into soft and hard overlapping areas. The authors in7 highlight the problem of imbalance and overlapping regions, where the probabilities of different class samples are almost equal having somehow similar characteristics. These similar data attributes make it very difficult for the traditional classifiers to separate the samples of different classes from each other.

Das et al.31 investigate the overlapping issues by modifying the SVM kernel function to map lower-dimensional feature space into a high-dimensional space. This transformation helps make the original data more linearly separable. Additionally,32 suggests Tomek data purification techniques to deal with overlap issues. Wilson33 introduces the Edited Nearest Neighbor (ENN) rule, which uses convergence features of the nearest neighbors. Batistia and colleagues34 combine the ENN rule with SMOTE and Tomek techniques. They use ENN with SMOTE and SMOTE + Tomek to deal with overlapping problems.

Xiong et al.35 provide a systematic review of approaches to address data overlapping issues and the relationship between imbalance and overlapping data. Several simple ways are demonstrated by first identifying the overlapping region with a support vector description, and then utilizing different techniques to separate, merge, and reject the complex overlapped data. Data overlap is a major problem in machine learning and directly affects the generalization and classification performance of the model, claims36. The authors presented the kernel-MTS to improve classification performance in overlapping contexts. The kernel function significantly reduces both the computation quantity and dimensional complexity. The authors of16 devised a 2eSVM method that maps low-dimensional features into a higher-dimensional feature space using the classical SVM framework. The mapping in higher-dimensional space makes it easy for the classifier to apply the kernel function to separate the data linearly. After studying the existing literature it is clear that imbalance and overlapping are closely related to each other, as highlighted in37.

The authors propose a hybrid oversampling approach to effectively overcome the imbalance of classes, both inter- and intra-classes, and avoid noise formation. SMOTE combines k-means clustering and synthetic minority oversampling. Clustering, filtering, and sampling make up the three steps of the K-means-SMOTE38 approach. The k-mean clustering algorithm divides the input space into k subsets for grouping. A subset of clusters within each of the k groups is chosen in the second phase for sampling with an emphasis on minority class samples. In the third step, the sampling technique SMOTE is applied to each cluster to obtain an improved ratio of minority to majority samples. The suggested approach significantly enhances the classification results by oversampling the training data, according to extensive testing and empirical findings. Furthermore, k-means SMOTE is more often used than other well-liked oversampling techniques.

The study39 proposed an ensemble approach to work with imbalanced and class-overlapping data. The authors followed an integration of class overlap reduction and data undersampling to resolve this issue. Integration is done using an extreme gradient boosting model which showed superior results compared to existing benchmarks. Entropy-based sampling, particularly hybrid sampling is another attractive solution to this problem, as reported by Kumar et al.40. The entropy-based method is especially effective for highly class over and imbalanced problems. The method works by removing less information samples from overlapping areas and generates highly informative samples. Results show performance improvements for various imbalanced datasets.

The use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) is also reported to resolve data imbalance problems. For example,41 made use of GANs for classifying imbalanced datasets. The proposed approach comprises modules for misclassified samples and generated minority samples, in addition to GAN modules for discriminator and generator. Misclassified samples are iteratively updated along with the other modules. Experiments using tabular and textual data show better results than existing sampling approaches. Similarly, the study42 leverages GANs to overcome data imbalance problems. The authors introduced an adaptive weighting method which used local and global density approaches to identify noisy samples. Weights depend on the density of a sample and its proximity to neighboring instances. Later, GAN builds the balanced dataset with the generation of minority class samples using weights. An improved performance is reported using the GAN-generated balanced dataset.

Predominantly, existing works are based on data-level, algorithm-level, and hybrid approaches to address the problem of class overlapping issues in multi-class imbalanced datasets. Very few papers about the quantification of overlapping samples and the effect of these samples are reported in the literature43. Moreover, there is no well-defined mechanism to introduce a controlled overlapping sample in the underlying multi-class dataset to analyze the learning performance of a particular classifier. As a reason for the limited number of papers in the literature, here in this paper, we include some important references that demonstrate the class overlapping effect on learning from multi-class problems44.

From the previous study, one of the main issues relating to the classification of the problems having multiple classes is overlapping issues, even more challenging than the imbalance itself45. To address the issue of overlapping, differing studies like46,47,48 propose different sampling techniques to incorporate in data pre-processing steps, however, as pointed out in49,50,51, in the case of high dimensional imbalanced data, sampling techniques might not be enough to deal with the overlapping issue. The distribution density of the data, particularly in high dimensional feature space together with a minority class with a very small sample space makes it extremely challenging to differentiate the decision boundaries between the negative and positive (majority, minority) classes. At the same time, it is evident from the literature that most of the classifiers are designed by least focusing on how to handle the redundant features. Even if it is not guaranteed to get a better classification report as a result of redundancy problems after taking/using all the available features, forming a conclusion that features in high dimensional space are completely or partially unrelated to impartial learning52,53. In a highly imbalanced environment, some of the features become irrelevant because of the class overlapping issue (when some of the instances, fall into overlap regions of minority class and majority class). If the same situation is happening in various feature spaces, the recognition of positive and negative classes becomes extremely problematic. Henceforth, there is a resilient determination to search out strong, prevailing feature subsets of all existing features, especially in the classification of a multivariate dataset.

Quantification of class overlapping

As discussed in the previous section, most of the real-world problems exhibit overlapping issues when co-occurring with the imbalanced distribution of data, severely affecting the classification performance, as presented by Garcia et al. in30, proving that the learning difficulty of a classifier on an imbalanced dataset is highly dependent on the overlap degree. Despite being a popular field of research, there is currently no clear-cut mathematical explanation for how classes overlap, despite various studies in the literature2,54 being presented. A major limitation of these methods is that they assume the data follows a normal distribution, which is not valid for most real-world datasets. To address this, we modified the formula from21 in Eq. (2) for a better approximation of the overlapping region. This formula was originally intended for binary classification problems using a 2-dimensional feature space.

As shown in Eq. (2), the level of overlapping in the majority class influences the classification performance.

The closest neighbor rule and Euclidean distance are used to calculate the majority class area, and the shared feature space with comparable features is known as the overlapping region. The overlap zone for the two classes \(C_i\) and \(C_j\) can be calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4).

where \(x \in\) overlapping region sample.

The same must apply to class \(C_i\) if the probability density of that class is \(\ge 0\), meaning that the features of the class \(C_i\) sample and the class \(C_j\) sample are similar. Here, Eqs. (3) and (4) compute the similar sample that contributes to the overlapping region based on the probability density. Put simply, if a \(C_i\) class sample’s probability density is higher than zero, then the \(C_j\) class sample’s probability density must likewise be higher than zero for samples located in overlapped regions.

In this case, \(r_{fi}\) is the dataset’s feature \(f_i\)’s discriminative ratio. F1 initially stores the value of the largest discriminative ratio. You can also calculate \(r_{fi}\) using the formula described by Orrial in his research publication55, which is as follows:

where \(P_{C_i}\) and \(P_{C_k}\) denotes samples of class \(C_i\) and \(C_k\). Where \(\mu _{C_i}\) and \(\mu _{C_k}\) represent the value of features’ mean of the class samples of \(P_{C_i}\) and \(P_{C_k}\), consequently, while \(\sigma _{C_i}\) and \(\sigma _{C_k}\) indicate how those samples’ standard deviations are calculated. Equations (5) and (7) are both used to partition the underlying dataset into binary classification issues using a one-vs-one technique. An alternate formula for calculating the discriminative ratio is provided by Molliendia56. It is as follows:

where \(n_{c}\) represents the respective samples in class \(C_i\), and \(\mu _k\) denotes samples’ mean for class \(C_k\). The \(\mu\) shows features mean across all the classes, while \(x_{ik}\) is the individual value of \(f_k\) feature from a sample of class \(C_i\).

Based on vector direction, the Directional-vector Maximum Fisher’s Discriminative Ratio concept is presented in55, which pursues a vector that can separate the samples of two classes after being projected and is given by:

In Eq. (8), \(\textbf{v}\) represents the directional vector where the data is projected to exploit the class separation in the problem domain. The scatter matrix between the classes is denoted by \(\mathbf {S_b}\), and \(\mathbf {S_w}\) represents the scatter matrix within the class. \(\mathbf {S_b}\) and \(\mathbf {S_w}\) are defined in Eqs. (9), (10), and (11), respectively.

where \(\textbf{u}_{C_i}\) represents the mean vector or centroid of class \(C_i\), and \(\textbf{w}^{-1}\) denotes the pseudo-inverse of \(\textbf{m}_{C_i}\).

where \(\textbf{u}_{C_j}\) and \(\textbf{u}_{C_k}\) represent the mean vector or centroid of class \(C_j\) and \(C_k\), respectively.

where \(\textbf{p}_{C_i}\) and \(\textbf{p}_{C_k}\) are the sample proportions in class \(C_i\) and \(C_k\), respectively, and \(\textbf{S}_{C_i}\) and \(\textbf{S}_{C_k}\) denote the scatter matrices for classes \(C_i\) and \(C_k\), respectively.

Now using the definitions from Eqs. (9), (10), and (11), the directional-vector-based discriminative ratio can be computed as:

Lower values in dF indicate that the underlying problem is simple to project the samples in the data space by using a linear hyperplane to separate most of the data.

Overlapping occurs near the boundary region within the class in the problem domain. An important measure while quantifying overlapping samples is to find out the volume of the overlapping region57, and it is given by:

where,

\([\min \left\{ \max \left\{ f_{i} \right\} \right\} = \min \left( \max \left\{ f_{i}^{c1} \right\} , \max \left\{ f_{i}^{c2} \right\} \right) ]\)

\([maxmin(f_i)=max(min(f_i^c1), min(f_i^c2))]\)

\([\max \max (f_i) = \max \left( \max (f_i^{c1}), \max (f_i^{c2}) \right) ]\)

\([minmin(f_i) = min(min(f_i^c1), min(f_i^c2))]\)

The algorithm calculates the volume of overlapping samples within the class and the distribution of the feature values by finding the minimum and maximum values for each feature in all classes. The values \(\text {min}_i\) and \(\text {max}_i\) are the minimum and maximum values of each feature in a class.

General synthetic samples in multiclass datasets using proposed algorithms

In this section, different algorithms are designed to implement the proposed schemes that introduce a controlled synthetic overlapping in multi-class imbalanced datasets to show the impact of class overlapping on the underlying classifier.

Algorithms to synthetically overlap multi-class dataset

In the current research, four different algorithms are used to synthetically overlap the multi-class dataset, namely, Majority-class Overlapping Scheme (MOS), All-class Overlapping Scheme (AOS), Random-class Overlapping Scheme (ROS), and All-class Overlapping Scheme using SMOTE (AOS-SMOTE).

-

MOS: Synthetic samples are introduced in the majority class with a varying degree of 10. The MOS scheme targets only the majority class to create samples with a shared attribute in the overlapping region. The learning performance of the underlying classifier is evaluated directly on the multi-class dataset, and then 10% of samples are overlapped in the majority class. The percentage of overlapping samples is increased with an interval of 10 up to 50% to show the different levels of class overlapping effect on learning from multi-class problems. The MOS scheme further decreases minority class visibility by increasing the majority class samples, flushed even more with the increasing level, as clear from the result section.

-

AOS: All classes in the problem domain are considered as a target class to be synthetically overlapped. If the total number of classes is \(N\), then \(N\) sets of synthetic samples \(s_1, s_2, \ldots , s_N\) will be generated, which will then be merged with the original dataset. The degree of overlapping samples will be increased in the order as described in MOS.

-

ROS: Before applying any algorithm, SMOTE is applied to balance the sample distribution of the majority and minority classes. After applying SMOTE, a target class is selected randomly, and the proposed scheme generates only a single set of synthetic sample \(S_{\text {rand}}\) inserted into the target class, then merges with the original dataset \(D\).

-

AOS-SMOTE: All classes will be overlapped by applying SMOTE, here no synthetic samples will be created, only the minority class samples will be increased to become equal with the majority class samples using SMOTE.

To implement the proposed algorithms, some concepts are based on58 and59 reported in the literature.

Algorithms for the proposed schemes

The first strategy is implemented by Algorithm 1, where different levels of synthetic samples are only introduced to the majority class in order to increase the overlap with the varied level or degree of 10. The classifier’s learning is assessed at each level in order to examine the impact of overlapping at that particular level. The synthetic samples are added to the majority class in increments of 10, starting with 10% of the majority class samples generated using the MOS technique and increasing to 50%. This algorithm first identifies the samples from both classes and then employs Eq. (14) to determine the distance between samples from both classes.

where d is the separation between the two observes and a, b are two vectors (as an instance distribution). Using Eq. (15), the distance for the nth row point is

The working mechanism of the proposed algorithm is discussed in the subsequent section. Algorithm 1 is used to generate overlapping samples, SS, in the majority class of the multi-class dataset, where \(B = S = \emptyset\) at the beginning and k1 and k2 are two parameters indicating the number of neighbors and are prefixed.

Algorithm 2 is used for AOS. The idea is to build the set of overlapping samples, or SS, in each of the multi-class dataset’s classes (with \(B = SS = \emptyset\) initially; the number of neighbors is indicated by the prefixed parameters k1 and k2).

Algorithm 3 is used for for ROS. The idea is to apply SMOTE to a random class in the multi-class data set, and then generate the overlapping samples set denoted by S (originally B = S = \(\emptyset\); k1 and k2 are two prefixed parameters specifying the number of neighbors).

Working mechanism for all schemes

As discussed in the previous sections, the four schemes generate the synthetic samples according to a predefined level to highlight the overlapping effects in the underlying dataset. The three schemes follow the same working mechanism except for the selection of the target class to be overlapped. The explanation is based on Algorithm 3 and can be applied to all the schemes, consisting of three steps.

-

i.

Preprocessing step: This step involves applying several preprocessing to make it efficient for model training. For example, the Label-Encoding scheme converts the categorical data into numeric values. Using normalization techniques, the features are scaled to a range centered around zero, much like the underlying data.

-

ii.

Assessment of class samples to the overlapping region: As shown in Fig. 2b, the basic assumption regarding the class overlapping samples is that they comprise samples closest to the boundary. Based on this supposition, we identify target class samples that are near the boundaries. Line 9 of the algorithm determines the average distance \(dist\_i\) for each sample of the target class C and its \(k_1\) neighbors (\(NS_{ample}\)) who do not belong to the target class(es) and the target class. The nearest neighbor is selected by setting the value of \(k_1\) to 1. Euclidean distance is used to compute the distance \(dist\_i\) between the sample and its neighbor60. The closer the sample is to the boundary, the lower the sample’s \(d_i\) value. The detrimental effects of noise in the sample space will be lessened by a greater value of k. We obtain a triplet of four items as a result of this step: \(S_{ample}\) (single sample of class C), \(dist\_i\) (average distance to a sample of \(k_n\) class), \(maj\_i\) (target class), and \(NS_{ample}\) (the closest sample of the other than target class(es)). Euclidean distance can lose its effectiveness in high-dimensional datasets due to several issues including the distortion of distances in high-dimensional spaces and the curse of dimensionality. Since our data is not high-dimensional that’s why we prefer to use Euclidean distance because of its easiness and simplicity. If the data is high-dimensional, obviously we have to look for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or other approaches for dimensionality reduction. Since the data has a low-dimensional space, the Euclidean distance is considered. Figure 2a and c show imbalanced distribution and imbalanced and overlapping distribution, respectively.

As a matter of fact, regions in the feature space where instances from several classes are closely packed together, frequently cause data overlap. With the increasing number of overlapping samples, the underlying classifiers suffer in terms of accuracy, precision, etc. Figure 2 is a very clear depiction of the scenario which shows that more ambiguity in class boundaries is suggested by a higher density of mixed-class neighbors. Overlap is influenced by the geometric complexity of the decision boundary (linear vs. nonlinear separability) in addition to the closest-opponent rule. Since the datasets in this study, are not complex for any intrinsic characteristics of the data that call for intricate decision boundaries, how they overlap is not needed. In addition, the data has a low-dimensional space, which is why the class overlap is more visible, compared to the high-dimensional space data where data sparsity makes the overlap less pronounced. For this reason, this study demonstrates the synthetic creation of overlapped samples with controlled intrinsic characteristics to empirically demonstrate the effects of overlap.

-

iii.

Creation of the overlapping region via synthetic samples: \(SS = \left( \frac{\#T\_M\_SubSet \cdot x}{100}\right)\), the number of synthetic samples SS, where T_M_SubSet is the subset of \(Mul\_IOD\) that includes every sample of the target class C, can be found using (line 13). The distance determined in the preceding step is used to sort the samples of the target class in ascending order so that they can be processed sequentially. A synthetic sample SS, is created nearby for each sample. A random neighbor to its \(k_2\) nearest neighbor is chosen at random in line 17 of Algorithm 3, where the sample is from target class C, \(NS_{ample}\) is the selected neighbor, and r indicates a number (random) between 0 and 1. Sample SS is created using the interpolation scheme58. For nominal attribute, a random value between \(S_{ample}\) and \(NS_{ample}\) is selected.

The suggested scheme’s synthetic sample generation is based on SMOTE interpolation58, with the exception that \(k=1\) and \(k=3\) will be used to locate the other class’s closest neighbors. Equation (16) is applied to construct the new synthetic sample.

where rnd is a random number between (0, 1), \(S_{ample}\) is the selected sample from the training set of under consideration class (target class) and \(dist\_i\) is the distance between the selected sample \(S_{ample}\), and the nearest search sample from the class other than the target class using Euclidean distance formula. The distance \(dist\_i\) is computed using Eq. (17).

where \(dist_i\) is the difference between the selected sample \(S_{ample}\) and the neighbor’s sample \(S_{ample}\) of the other class.

Figure 3 shows the creation of synthetic samples from the target class sample \(S_{ample}\). Four different samples r1, r2, r3, and r4 are created which are different from the target class samples. Here, in this case, \(S_{ample}\) is the original sample of the target class. We set \(K=1\) to find the near neighbor other than the target class, which are \(S_{ample}1\), \(S_{ample}2\), \(S_{ample}3\), and \(S_{ample}4\) as mentioned in Fig. 3. To do this, the difference between each of the chosen neighbors and the feature vector (sample) under consideration is calculated. The previous feature vector is multiplied by a random value between 0 and 1, after which the difference is appended.

Figure 4 shows the mathematical description of how to create synthetic samples from the target class. A distance vector is maintained to hold the distance of all the nearest samples not belong to the target class.

Figure 5 shows the creation of synthetic samples and Fig. 6 shows a mathematical description of how to create synthetic samples from the same target class. The difference between Figs. 4 and 5 is the creation of synthetic samples from other than the target class and from the target class. In Fig. 5 four different samples r1, r2, r3, and r4 are created from the same target class to which sample \(S_{ample}1\) belongs. The mathematical description shows how a synthetic sample was created from the target class sample \(S_{ample}1\). A distance vector is maintained to hold the distance of all nearest samples belonging to the same target class from which sample \(S_{ample}1\) is selected.

Figure 6 shows the description of generating synthetic samples using target class C.

Results and discussions

Experimental setup

In the current research, four different schemes are implemented via algorithms to synthetically overlap the multiclass dataset using the four sachems, namely, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE. The real dataset which is used for experiments is also discussed with the relevant information. Results are also presented and discussed in this section.

Choice of evaluation metrics

Accuracy, precision, and F1 scores are employed for model evaluation for the following reasons.

-

Easy Communication and Ease of Understanding: Accuracy is straightforward to calculate and explain for stakeholders who are not technical. This is the simplest method to convey “how often the model gets things right.”

-

Precision draws attention to the significance of positive predictions, which is helpful in situations where false positives are crucial. For greater insights, precision is frequently combined with recall (e.g., F1 score).

-

Initial Metric: Even in unbalanced datasets, accuracy is frequently employed as a baseline statistic or starting point for preliminary testing. Quickly determining whether the model is performing worse than random guessing is helpful. When concentrating on the performance of positive predictions in the early phases of analysis, precision can be helpful, and most importantly accuracy and precision provide deep insights where the samples in classes are equally distributed or, even in the situation where the imbalanced nature of data can be handled easily.

In this study, since we create synthetic overlapped samples, it would be better to test the performance of the model as a baseline metric of accuracy and precision to show the worst performance in case imbalanced samples are increasing, and it is more convenient for the initial evaluation of the model.

Class overlapping effect on learning from multi-class real-world dataset

This study utilized 20 real-world datasets for experiments which can be found on the UCI repository61. The selection of the datasets is based on various characteristics; for example, the attributes in a dataset, the total number of samples and the number of classes, as well as, the distribution of samples for those classes. Every dataset is different concerning these characteristics. For example, the number of samples is from 150 to 12960, features are between 4 to 65, and classes can be any number between 3 and 20, as shown in Table 1.

Analysis of results for effect of imbalance and overlapping

For experiments, synthetic-generated samples were added to the multi-class datasets to increase both the imbalance and the overlapping effect, using the proposed schemes, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE, discussed in the previous section. A range of values for each classifier’s various parameters are tested in this study using grid search and ten-fold cross-validation. This process is run to find the optimal parameter configuration that would produce the best overall classification accuracy and precision for each classifier.

For SVM, we adjusted the gamma parameter within the 20-value search range and chose “100” as the optimal value, “0.1” for C, “O-vs-R” for the decision function shape, and “uniform” for the class-weight parameter. For KNN, n-neighbors is “5”, weights are “uniform”, and leaf-size is “3”. For RF2 min-samples-leaf = “2”, number-of-estimators = “00”, and nax-features = “all”.

Here, we present the effect of the synthetic samples on some well-known classifiers like SVM, KNN, and RF by measuring their accuracy, precision, and F1 scores. We have used ten-fold cross-validation to split the samples in the training and testing set. Table 2 highlights the results for proposed schemes with different degrees of overlapping on the Ecoli dataset. In the experiment part of this research, we implemented the proposed schemes for 20 multi-class datasets, but only the results of the Ecoli and Vehicle datasets are presented here.

The first section of Table 2, displays results for the MOS scheme, where synthetic samples are added to the dataset. Here we are not concerned about the working mechanism or the performance comparison of the underlying classifiers; rather we are interested in discussing how much the learning capability of the classifier is affected by increasing the overlapping samples with varying degrees of 10. It is evident from Table 2, that at 0% (when there is no synthetic overlapping), all three classifiers give maximum learning over the Ecoli dataset. However, with the increasing degree of overlapping, the learning accuracy decreases gradually for all the classifiers, with the worse performance at 50% of the synthetic overlapping. The accuracy results reveal that the overlapping degree gradually decreases with the increasing degree of overlapping. Most of the time majority-class observations largely contribute to the overlapped region, while the minority-class samples are less focused. If we synthetically generate samples to the majority class based on the distance with the other class sample, the samples for the minority class reduce, even more, causing a dramatic decrease in the accuracy and precision. With the increasing degree of overlapping, an optimal hyperplane becomes very difficult for the underlying classifiers to detect the boundary. In this case, the classifier may predict the sample of the minority class as the sample of the majority class, which leads to an impractical classification model by compromising overall performance.

In the second section of Table 2, results for the AOS scheme are presented by overlapping all the classes in the dataset by inserting the synthetic samples. If we compare the MOS and AOS schemes, the former schemes proved their significance over the latter scheme. In the MOS scheme, synthetic samples were added only in the majority class, thus affecting the overlapping region of the majority class with the rest of the classes, whereas in the AOS scheme, synthetic samples were inserted in all the classes, thus enlarging the overlapping region among all the classes in the dataset.

The ROS scheme, selects a random class for the synthetic samples at a different level of overlapping, thus at each level every time a different class is overlapped synthetically. If we compare the ROS scheme with MOS and AOS, ROS gives inconsistent results for both accuracy and precision. The reason behind the inconsistent results is the random selection of classes, such that, the Ecoli dataset consists of 8 classes with unequal distribution of samples, the first class (majority class) having 143 samples, and the rest of the classes have different samples (less than 143). Now if a class with 10 samples is selected randomly, according to the formula used in the proposed algorithm, only one or two synthetic samples can be added to that class. With these two synthetic samples, almost there will be no effect on the overlapping region.

In the AOS-SMOTE scheme, SMOTE balances the distribution of samples in the majority and minority class (es). After a balance distribution, a random class is selected to overlap by inserting synthetic samples. Instead of random selection, we can insert the synthetic samples in any class, as all the classes have an equal number of samples showing the same effects. The results for existing overlapping data (without inserting synthetic samples, 0%) revealed that all three classifiers show better performance as compared to the three schemes. The SMOTE oversampling technique is the main reason behind this improved performance. SMOTE algorithm also synthetically generates samples to insert into the minority classes, to bring them equal to the majority class sample. The rest of the results are nearly consistent for different degrees of overlapping, gradually decreasing with the increasing degree of overlapping. Figures 7a–d show the respective graphs for the four proposed schemes: MOS, AOS, ROS and AOS-SMOTE concerning accuracy.

Figures 8a–d are the respective graphs for the four proposed schemes, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE by evaluating the precision. The model reports different precision for the proposed schemes. For the MOS and AOS schemes, SVM performs better while RF leads precision for ROS and AOS-SMOTE methods.

Table 3 highlights the comparative results for all three classifiers, SVM, KNN, and RF, for MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE schemes for different degrees of overlapping using the Vehicle dataset. It is evident from the overall effect of synthetic class overlapping for both the dataset over all the four schemes, the increasing degree of overlapping has more effect on the Vehicle dataset as compared to the Ecoli dataset. The learning of the underlying classifier is more affected in the Vehicle multi-class imbalance dataset with the increasing degree of synthetic overlapping. The Ecoli dataset consists of 336 samples with 8 classes and 9 features, whereas the Vehicle dataset consists of 846 samples with 19 features and 4 classes. The majority class in Ecoli dataset has 143 samples, while the rest of the 193 samples distributed in the seven classes with frequencies (0:143, 1:77, 2:2, 3:2, 4:35, 5:20, 6:5, 7:52). If we look at the distribution, some of the classes have a very less number of sample, such that, two, two, and five samples, according to the overlapping degree there will be no synthetic sample for those classes even in case of 10% overlapping, thus greatly minimizing the overlapping region after the synthetic generation of samples. On the other hand, the distribution of vehicle dataset samples, (0:218, 1:212, 2:217, and 3:199), for every class, even with the lowest degree of overlapping (10%), a notable synthetic sample generates and added to the overlapped region. Getting more samples in the overlapping region makes it difficult for the classifier to correctly predict the target class, the misclassifying rate increases with the increasing number of samples, compromising the overall classification performance.

Figure 9a–d are the respective graphs for the four proposed schemes, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE by evaluating the accuracy. Figure 10a–d show the representative graphs for models’ precision when used with the four proposed schemes.

Table 4 highlights the comparative results for all three classifiers, SVM, KNN, and RF by employing standard procedure, by MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE scheme for different degrees of overlapping using the Ecoli dataset to measure the F1 score. Similar to the results reported in Tables 2 and 3 for accuracy and precision for the proposed schemes, the performance is better when generating a low ratio of synthetic samples.

Figure 11a–d are the respective graphs for the four proposed schemes, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE for F1 scores. The F1 score varies with respect to the approach for generating synthetic samples, as well as, the ratio of sample generation. Increasing the ratio of generated samples tends to degrade models’ performance.

Table 5 highlights the comparative results for all three classifiers, SVM, KNN, and RF by employing standard procedure for MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE scheme for different degrees of overlapping using the Vehicle dataset to measure the F1 score.

Figure 12a–d are the respective graphs for the four proposed schemes, MOS, AOS, ROS, and AOS-SMOTE by evaluating the accuracy and precision. SVM tends to show a better F1 score at 50% oversampling method for all the four proposed schemes.

Limitations of the study

This study proposes several approaches for the synthetic oversampling of data to alleviate the impact of class overlapping which is an important topic in terms of dealing with the lower performance of classifiers. Experiments on several datasets containing overlapped and imbalanced class samples are run to analyze models’ performance. Although better results compared to existing approaches are reported, the study has several limitations.

-

For class overlapping, only the closest opponent rule is considered with respect to the nature of the datasets used in this study. However, other rules such as the local density of nearest instances in a class, types of data distribution, etc., might provide valuable insights into this problem.

-

For nearest neighbors, the Euclidean distance metric is considered only in this study, because the dataset has a low-dimensional space. However, other distance calculation metrics can also be used to determine class overlapping.

-

This study considered several datasets to run experiments, however, only low-dimensional datasets are considered alone, necessitating further experiments using high-dimensional datasets.

Conclusions

Class overlapping is a challenging issue that degrades the learning of classifiers and severely affects their performance, even more so for multi-class datasets. In the literature, many studies use data-level, algorithm-level, or hybrid techniques to solve class overlapping difficulties. However, a well-presented study that demonstrated the impact of increasing levels of sample overlap on the performance of the classifier could not be found. Our contribution in this paper is to design and implement four different schemes (algorithms) to generate different levels of synthetic samples in the multi-class imbalanced datasets to make them more overlap and imbalance. In this way, we can conclude (based on the results), that how much a particular level of overlapping samples hinders the learning of the classifiers from multi-class imbalanced problems. Four different schemes used for synthetic controlled overlapping are majority-class oversampling (MOS), all-class oversampling (AOS), random-class oversampling (ROS), and AOS using SMOTE (AOS-SMOTE). Each proposed scheme in this paper generates a controlled overlapping, starting from 0 up to 50% with an interval of 10, and inserts into the underlying multi-class dataset. The synthetically overlapped multi-class dataset is then classified via three well-known classifiers, support vector machine, k nearest neighbor, and random forest, to show how much learning of these classifiers compromises with the increasing degree of overlapping.

This research provides a means for extensive evaluation of different samples in the dataset implying a novel concept of understanding the class overlapping and evaluating how the classifier’s performance is affected for multi-class datasets. In the future, the researchers can exactly estimate the correlation between the degree of overlapping and a classifier’s performance, to focus on features engineering, data cleansing, and data preprocessing methods in combination with decomposition techniques to enhance the classifier’s performance while dealing with multi-class imbalanced problems in class overlapping.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be requested from the corresponding authors.

References

Lee, I. & Shin, Y. J. Machine learning for enterprises: Applications, algorithm selection, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 63(2), 157–170 (2020).

Lee, H.-K. & Kim, S.-B. An overlap-sensitive margin classifier for imbalanced and overlapping data. Expert Syst. Appl. 98, 72–83 (2018).

Santos, M. S. et al. On the joint-effect of class imbalance and overlap: A critical review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55(8), 6207–6275 (2022).

Rendón, E. et al. Data sampling methods to deal with the big data multi-class imbalance problem. Appl. Sci. 10(4), 1276 (2020).

Prati, R. C., Batista, G. E. & Monard, M. C. Class imbalances versus class overlapping: An analysis of a learning system behavior. In Mexican International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Springer, 2004).

Hanskunatai, A. A new hybrid sampling approach for classification of imbalanced datasets. In 2018 3rd International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS). (IEEE, 2018).

Lango, M. & Stefanowski, J. J. ESw. A. What makes multi-class imbalanced problems difficult? An experimental study. Exp. Syst. Appl. 199, 116962 (2022).

Fu, G.-H. et al. Feature selection and classification by minimizing overlap degree for class-imbalanced data in metabolomics. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 196, 103906 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Strength of ensemble learning in multiclass classification of rockburst intensity. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 44(13), 1833–1853 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Multiclass imbalanced learning with one-versus-one decomposition and spectral clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 147, 113152 (2020).

Lim, L.-W. & Singh, M. Resolving the imbalance issue in short messaging service spam dataset using cost-sensitive techniques. J. Inform. Secur. Appl. 54, 102558 (2020).

Fu, M., Tian, Y. & Wu, F. Step-wise support vector machines for classification of overlapping samples. Neurocomputing 155, 159–166 (2015).

Chen, X.-w. & Jeong, J.C.: Enhanced recursive feature elimination. In Sixth International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA 2007) (IEEE, 2007).

Venter, G. Review of optimization techniques. In Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering (2010).

Park, J. H. & Fung, P. One-step and two-step classification for abusive language detection on twitter. arXiv:1706.01206 (2017).

Czarnecki, W. M. & Tabor, J. Two ellipsoid support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 41(18), 8211–8224 (2014).

Zhang, W. & Gao, F. An improvement to Naive Bayes for text classification. Procedia Eng. 15, 2160–2164 (2011).

Xiong, H. et al. Classification algorithm based on NB for class overlapping problem. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci 7(2L), 409–415 (2013).

Rahm, E. & Do, H.-H. Data cleaning: Problems and current approaches. IEEE Data Eng. Bull. 23(4), 3–13 (2000).

Kaur, P. & Gosain, A. Robust hybrid data-level sampling approach to handle imbalanced data during classification. Soft. Comput. 24(20), 15715–15732 (2020).

Vuttipittayamongkol, P. & Elyan, E. Neighbourhood-based undersampling approach for handling imbalanced and overlapped data. Inf. Sci. 509, 47–70 (2020).

Han, Wang, W. -Y. & Mao, B.-H. Borderline-smote: A new over-sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. In: International Conference on Intelligent Computing (Springer, 2005).

Kaka, J. R. & Satya Prasad, K. Differential evolution and multiclass support vector machine for Alzheimer’s classification. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022(1), 7275433 (2022).

Mehmood, Z. & Asghar, S. Customizing SVM as a base learner with adaboost ensemble to learn from multi-class problems: A hybrid approach adaboost-msvm. Knowl. Based Syst. 217, 106845 (2021).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News 2(3), 18–22 (2002).

Dudani, S. A. The distance-weighted k-nearest-neighbor rule. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 6(4), 325–327 (1976).

Xuegong, Z. Introduction to statistical learning theory and support vector machines. Acta Autom. Sin. 26(1), 32–42 (2000).

Keskes, N. et al. High performance oversampling technique considering intra-class and inter-class distances. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 34(6), 6753 (2022).

Denil, M. & Trappenberg, T. Overlap versus imbalance. In Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Springer, 2010).

García, V., Mollineda, R. A. & Sánchez, J. S. On the k-nn performance in a challenging scenario of imbalance and overlapping. Pattern Anal. Appl. 11(3–4), 269–280 (2008).

Qu, Y. et al. A novel SVM modeling approach for highly imbalanced and overlapping classification. Intell. Data Anal. 15(3), 319–341 (2011).

Tomek, I. Two modifications of CNN. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 6, 769–772 (1976).

Wilson, D. L. Asymptotic properties of nearest neighbor rules using edited data. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 3, 408–421 (1972).

Batista, G. E., Prati, R. C. & Monard, M. C. A study of the behavior of several methods for balancing machine learning training data. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 6(1), 20–29 (2004).

Xiong, H., Wu, J. & Liu, L. Classification with classoverlapping: A systematic study. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on E-Business Intelligence (ICEBI2010) (Atlantis Press, 2010).

Jing, Z. et al. Building Tianjin driving cycle based on linear discriminant analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 53, 78–87 (2017).

Krawczyk, B. et al. Dynamic ensemble selection for multi-class classification with one-class classifiers. Pattern Recogn. 83, 34–51 (2018).

Liao, J.-J. et al. An ensemble-based model for two-class imbalanced financial problem. Econ. Model. 37, 175–183 (2014).

Dar, A. W. & Farooq, S. U. An ensemble model for addressing class imbalance and class overlap in software defect prediction. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 15(12), 5584–5603 (2024).

Kumar, A., Singh, D. & Yadav, R. S. Entropy-based hybrid sampling (ehs) method to handle class overlap in highly imbalanced dataset. Expert. Syst. 41(11), 13679 (2024).

Yun, J. & Lee, J.-S. Learning from class-imbalanced data using misclassification-focusing generative adversarial networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 240, 122288 (2024).

Guan, S., Zhao, X., Xue, Y. & Pan, H. Awgan: An adaptive weighting GAN approach for oversampling imbalanced datasets. Inf. Sci. 663, 120311 (2024).

Kumar, A., Singh, D. & Shankar Yadav, R. Class overlap handling methods in imbalanced domain: A comprehensive survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 63243–63290 (2024).

Santos, M. S., Abreu, P. H., Japkowicz, N., Fernández, A. & Santos, J. A unifying view of class overlap and imbalance: Key concepts, multi-view panorama, and open avenues for research. Inform. Fus. 89, 228–253 (2023).

Weiss, G. M. Mining with rarity: A unifying framework. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 6(1), 7–19 (2004).

Alejo, R. et al. A hybrid method to face class overlap and class imbalance on neural networks and multi-class scenarios. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 34(4), 380–388 (2013).

Abdi, L. & Hashemi, S. To combat multi-class imbalanced problems by means of over-sampling techniques. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 28(1), 238–251 (2016).

Yang, Z. & Gao, D. Classification for imbalanced and overlapping classes using outlier detection and sampling techniques. Appl. Math. 7(1L), 375–381 (2013).

Wasikowski, M. & Chen, X.-w. Combating the small sample class imbalance problem using feature selection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 22(10), 1388–1400 (2010).

Longadge, R. & Dongre, S. Class imbalance problem in data mining review. arXiv:1305.1707 (2013).

Khoshgoftaar, T. M., Gao, K. & Seliya, N. Attribute selection and imbalanced data: Problems in software defect prediction. In 2010 22nd IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (IEEE , 2010).

Yu, L. & Liu, H. Feature selection for high-dimensional data: A fast correlation-based filter solution. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-03) (2003).

Almuallim, H. & Dietterich, T. G.: Learning with many irrelevant features. In AAAI (Citeseer, 1991).

Sun, H. & Wang, S. Measuring the component overlapping in the gaussian mixture model. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 23(3), 479–502 (2011).

Nettleton, D. F., Orriols-Puig, A. & Fornells, A. A study of the effect of different types of noise on the precision of supervised learning techniques. Artif. Intell. Rev. 33, 275–306 (2010).

Mollineda, R. A., Sánchez, J. S. & Sotoca, J. M. Data characterization for effective prototype selection. In Iberian Conference on Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis (Springer, 2005).

Lorena, A. C. et al. How complex is your classification problem? A survey on measuring classification complexity. ACM Comput. Surv. 52(5), 1–34 (2019).

Fernández, A. et al. Smote for learning from imbalanced data: progress and challenges, marking the 15-year anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 61, 863–905 (2018).

Sáez, J. A., Galar, M. & Krawczyk, B. Addressing the overlapping data problem in classification using the one-vs-one decomposition strategy. IEEE Access 7, 83396–83411 (2019).

Danielsson, P.-E. Euclidean distance mapping. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 14(3), 227–248 (1980).

Lichman, M. UCI machine learning repository (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZM conceptualization, data analysis and writing—the original draft. MS formal analysis, data curation and methodology. AS software, methodology, project administration. SA acquired the funding for research, investigation, and visualization. IA supervision, validation and writing—review and edit. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmood, Z., Safran, M., Abdussamad et al. Algorithmic and mathematical modeling for synthetically controlled overlapping. Sci Rep 15, 7517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87992-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87992-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A deep learning framework with hybrid stacked sparse autoencoder for type 2 diabetes prediction

Scientific Reports (2025)