Abstract

It is a common occurrence in the fracture processes of deep carbonate reservoirs that the fracturing construction pressure during hydraulic fracturing operation exceeds 80 MPa. The maximum pumping pressure is determined by the rated pressure of the pumping pipe equipment and the reservoir characteristics, which confine the fracture to the target area. When the pump pressure exceeds the safety limit, hydraulic fracturing has to reduce the construction displacement to prevent potential accidents caused by overpressure. Therefore, real-time prediction of the fracturing construction pressure and diagnosis of abnormal fluctuations during hydraulic fracturing of highly deviated wells are indispensable. Based on the well trajectory, pumping process, and string structure of highly deviated wells, a movement interface model for the fracturing fluid at different stages within the wellbore has been established, using the method of computational fluid dynamics. This model analyzes the fluid movement behavior with diverse properties at various fracturing times and determines the relationship between the pressure changes at the leading and trailing edges of fluid movement in each section of the wellbore over time by combining different string structures and preset pumping procedures. The frictional pressure within the wellbore fluid, the hydrostatic fluid pressure, and the near-well friction drags have been calculated and predicted. A real-time prediction model for diagnosing pumping fracturing has been constructed to further comprehend “abnormal” fracturing construction pressures in highly deviated wells. This offers a theoretical foundation for the correct diagnosis and decision-making regarding hydraulic fracturing in highly deviated wells while guiding its smooth implementation in real time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wellbore pressure prediction is constantly demanded in oil and gas wells to monitor fluid movement within and around the wellbore. Petroleum wells typically produce a mixture of liquid and gas at the surface, and the phase distribution varies due to pressure changes along the flow path. High deviation well-fracturing techniques have demonstrated outstanding adaptability and economic benefits in exploring low-permeability and complex reservoirs, emerging as an influential technique for their development. In the hydraulic fracturing processes of highly deviated wells, a higher pumping rate is necessary to effectively convey proppant and generate a sufficiently high fracturing pressure. Extreme pump pressures (typically > 80 MPa) are common during the fracturing operations of highly deviated wells. The pump pressure limit is governed by the pressure of the pump string device and the reservoir characteristics that restrict the fracture target layer. When the pump pressure exceeds the safe range, it must be halted to prevent accidents caused by overpressure. Hence, it is necessary to predict the surface treatment pump pressures during the hydraulic fracturing processes of highly deviated wells.

Since 1970, diverse forms of literature have addressed the significance of precise knowledge regarding bottom-hole fracturing pressure. Perkins et al. (1961) and Nordgren (1972) demonstrated that by appropriately interpreting the slope of log net fracture pressure versus log time, it is feasible to interpret normal extension with confined height, fracture height growth with extension, fluid loss control due to hairline fracture opening, and runaway growth of fracture height for fractures conforming to the fracture geometry1,2. Nolte and Smith (1979) drew industry attention to the value of this information in predicting fracturing conditions3. Nolte also illustrated that post-fracturing pressure decline data could be employed to predict certain other fracturing parameters such as fracture height, leak-off coefficient, length, width, and closure time4. Hannah et al. (1983) devoted a discussion to the equipment utilized and its response time, correlation of friction and head data, as well as comparisons to real measured bottom-hole pressures5. A crucial aspect in such simulations is the development of computer software capable of rapidly reading and averaging data in order to keep pace with the variables.

Currently, conventional hydraulic fracturing is the more prevalently employed method. In this process, the fracturing pump typically operates at a constant speed, and the injection of fracturing fluid is stable. In recent years, there has been growing attention devoted to research regarding unstable injection, although it has mainly been focused on laboratory or industrial tests. Zhuang et al. conducted a test on granite samples from enhanced geothermal systems using a true triaxle hydraulic fracturing test system6,7. They compared pressure variation, acoustic emission amplitude, and fracture morphology in different injection schemes and found that unstable injection can increase fracture complexity and reduce breakdown pressure8,9,10,11,12. However, due to the space constraints in the laboratory setting, the test pipe string is short and cannot simulate dynamic pressure propagation in practical applications over hundreds to thousands of meters. Jordan et al. demonstrated through field testing of shale gas wells that an unstable injection scheme involving variations in pump speed can significantly enhance shale gas production13.

However, due to the intricate environment in the field, controlling test factors is challenging, monitoring means are restricted, and costs are elevated. In contrast, there is a dearth of theoretical research on hydraulic fracturing with unstable injection. Lu et al.14 and Yoon et al.15 respectively studied the stress distribution in a two-dimensional model under unstable excitation using the finite difference method and the discrete element method. The results indicated that unstable injection can enhance fracturing effectiveness. However, these studies only took the reservoir into account and neglected the flow of fracturing fluid along the string. Tong et al. established a mathematical model of unsteady fluid flow in the wellbore but did not consider the influence of fluid compressibility and friction. The essence of unstable injection lies in dynamically controlling the fluid flow in the pipe string by adjusting the injection rate and obtaining the fluid pressure at the bottom hole16. Zhu et al. (2020) respectively established transient flow models for the fluid in the pipe string and elastodynamic models for the reservoir. They also analyzed the characteristics of pressure propagation along the pipe string and the dynamic stress distribution in the reservoir. They discussed how the parameters in pulse injection schemes affect the engineering applications of pulse injection, providing valuable theoretical guidance for such applications17. Several mechanistic and empirical models have been developed to estimate the pressure drop inside the tubing in a vertical well. The majority of empirical models and correlations were formulated at a laboratory scale, which may result in decreased accuracy when applied to field situations18. Numerous studies have indicated that these empirical correlations often lead to significant errors and high levels of uncertainty when estimating pressure drop in multiphase flowing wells19. Mechanistic models are based on theoretical approaches for calculating multiphase flow characteristics such as mixture densities, flow patterns, and liquid hold-ups20,21,22.

The past two decades have witnessed a substantial growth in the application of computational intelligence (CI) in diverse areas of geosciences, petroleum engineering (PETE) and the design of horizontal well trajectories for hydraulic fracturing23,24. The significance of CI in PETE applications lies in its ability to handle the copious amounts of data generated in the field, such as seismic data, petrophysical well log data, and fracturing pressure curves and production data25,26,27,28. A literature review indicates that CI methods can be employed to estimate flowing bottomhole pressure (FBHP). Unlike previous analytical and mechanistic models, which are based on parameters determinable through laboratory analysis, these models are incapable of providing real-time FBHP values under existing operating conditions29,30,31. Furthermore, the execution of these models is computationally costly. An artificial neural network (ANN) is regarded as one of the most powerful and robust computational intelligence (CI) tools for addressing complex nonlinear problems32. These problems encompass function approximation, pattern recognition, parameter selection, as well as automated control and optimization33. Recent progress in the field of neural networks mathematics has resulted in their wide acceptance in the petroleum industry for their capability to solve complex and nonlinear problems34. The petroleum industry has manifested significant interest in employing CI techniques to predict bottom-hole flowing pressure (FBHP) in oil and gas wells. Osman et al. (2005) developed a model using artificial intelligence (AI) tools for estimating FBHP based on 300 data points35. Jahanandish et al. (2011) also presented an ANN model for BHP estimation36. To improve the accuracy of the ANN model, they employed the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm to optimize the weights and biases of the trained neural network for predicting FBHP37. Awadalla (2016) and Tariq (2019) proposed converting the ANN model into a simple mathematical form by extracting the optimized weights and biases38,39. Li et al. (2024) employed a hybrid neural network, integrating artificial neural networks (ANN) with bidirectional gated recurrent units (BiGRU), to undertake a comprehensive assessment of 22 influential factors, such as construction parameters, physical parameters, and well layout, and analyzed the variations in thermal breakthrough time and production temperature under different fracture densities40. Abdulwarith et al. (2024) constructed a data-driven model for predicting pipeline pressure loss based on the results of flowline test circuits, wellhead pressures, and total frictional losses. The total frictional losses utilized in the model were originated from the field data during the hydraulic fracturing stage of several wells. The flow line test circuits were modelled for a specific type of friction reducer, concentration, and flow rate41. Muther et al. (2022) demonstrates the application of three fresh socio-inspired algorithms in hydraulic fracturing optimization, integrating reservoir simulation, artificial neural networks, and prior optimization algorithms to obtain the optimized hydraulic fractures42.

Owing to the constant variation of the well trajectory and inclination angle in a highly deviated well with a large displacement, the relationship between the frictional pressure of the fracturing fluid and the fluid static pressure during the fracturing process of such a well differs from that of a vertical well. The fluid friction model for a vertical well is inapplicable to the fluid friction pressure analysis of a highly deviated well with a large displacement. Furthermore, during the hydraulic fracturing process, the fracturing fluid in the wellbore carries proppant, making the fluid flow friction more complicated. Hence, there is an urgent requirement for an accurate fracturing fluid flow friction pressure model to calculate the fluid friction pressure during the fracturing process of a highly deviated well with a large displacement, so as to precisely determine the wellhead construction pressure.

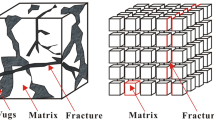

At present, there are merely a handful of precise fluid friction resistance prediction models specifically tailored for highly deviated wells. Hence, in contrast to vertical wells, predicting the frictional resistance and pumping construction pressure during the hydraulic fracturing of highly deviated wells confronts a more arduous challenge. Consequently, predicting and diagnosing the pumping construction pressure throughout the entire hydraulic fracturing process of highly deviated wells is extremely crucial, so that judicious decisions can be made in response to abnormal pumping pressure fluctuations during the fracturing process. In light of the theory of computational fluid dynamics, it computes the changes in pressure and frictional resistance of the fracturing fluid in the wellbore of highly deviated wells, the perforation hole, and the near-wellbore fracture, and establishes a model of the movement interface of the fracturing fluid carrying proppant in the wellbore (Fig. 1). It acquires the force conditions of the fracturing fluid at any position within the wellbore and calculates the fracturing construction pressure, which is conducive to analyzing abnormal pumping pressure during the fracturing process and resolving complex problems in the wellbore in a timely and effective manner.

Mechanism analysis of abnormal fracturing construction pressure

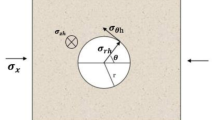

The composition of fluid and friction pressure in a large-displacement bore is presented in Fig. 2. The fracturing construction pressure of highly deviated wells comprises wellbore hydrostatic pressure, wellbore fluid friction pressure, perforation and near-wellbore friction, and formation fracture pressure (or bottom hole operation pressure)43,44.

Pstp — Ground fracturing construction pressure, MPa. Pbhtp — Bottom hole operating pressure or formation fracturing pressure, MPa. Pf — Wellbore friction pressure, MPa. Ppnwb — Perforation and near-wellbore friction, MPa. Ph — Wellbore hydrostatic pressure, MPa.

Influence of wellbore hydrostatic pressure and wellbore friction

The hydrostatic and frictional pressures within the borehole are affected by the introduction of a proppant into the pumped fracturing fluid. Ground teams inject sand mixed with various fluid densities into the wellbore at different stages. The density of the sand-mixed fluid undergoes alterations throughout the fracturing process. Hence, it is crucial to monitor the density variation of the injected fluid and track the relative position of the sand-mixed fluid with different densities in the wellbore at different times, in order to precisely determine the fluctuations in wellbore hydrostatic pressure and friction pressure during various treatment stages.

Owing to the complexity of highly deviated well trajectories and the rheology of fracturing fluid, modelling the fluid friction pressure in highly deviated wells is a challenging task. Various factors such as treatment conditions, the unique chemical properties of the fracturing fluid, different cross-linking degrees, and shear sensitivity can all exert an impact on the fluid friction pressure45,46. Predicting the friction pressure of a linear cross-linked or delayed cross-linked fracturing fluid is relatively straightforward, but it becomes more arduous for partially cross-linked fluids. These inherent difficulties in predicting fluid friction pressure can significantly undermine the accuracy of the well-bore fluid friction pressure prediction.

The impact of proppant on friction pressure within the pipe string is examined in this discussion. A model has been developed to predict fluid friction pressure, drawing from both experimental and field-measured data47,48. However, due to various factors such as the influence of proppant on fluid rheology, variations in proppant specifications, the complexity of well structure, changes in fluid flow patterns, and inaccuracies in predicting basic fluid friction pressure, it proves challenging to establish a prediction model for fluid friction pressure in highly deviated wells. Keck46 asserts that precise calculation of bottom hole pressure during fracturing treatment cannot be relied upon due to potential errors in calculating friction pressure within the pipe string. The preferred approach is direct measurement of formation fracture pressure using a bottom hole pressure recorder or static tubing string during field implementation. Nevertheless, the application and extension of these methods are somewhat constrained by treatment and economic considerations.

If the bottom-hole pressure recorder is used to directly measure the bottom-hole pressure, the result of the measurement is a superposition of all the pressures formed under the pressure gauge, separating the well-bore friction pressure, the bottom-hole operating pressure, and the perforation friction pressure. If the friction pressure in the string is combined with the friction pressure in the perforated hole and in the vicinity of the borehole, then the pressure measured by the bottom hole pressure recorder Pbhg is:

The bottom hole pressure recorder can also measure the hydrostatic pressure and wellbore friction pressure above the pressure measuring tool, according to formulas (1) and (2).

Pf-Ph is the net wellbore pressure above pressure measuring tool. In highly deviated wells, the wellbore hydrostatic pressure is calculated based on the true vertical depth of the wellbore true vertical depth (TVD), while the fluid friction pressure in the string is calculated based on the measured depth of the wellbore measure depth (MD). When the true vertical depth TVD of the highly deviated well remains unchanged, the measured depth MD of the wellbore increases with the increase of the well deviation angle, resulting in the rise of the friction pressure in the string, which is different from the relationship between the hydrostatic pressure and the friction pressure in the vertical wellbore. Due to the increasing concentration of proppant added during the fracturing operation, the density of fracturing fluid in the wellbore increases, and the hydrostatic pressure and friction resistance in the wellbore increase respectively. When the incremental change of total wellbore friction pressure exceeds the incremental change of corresponding hydrostatic pressure, the net wellbore pressure above the pressure measuring tool Pf−Ph will rise, which causes wellhead treatment pressure Pstp to rise.

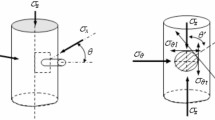

Influence of perforation and fracture bending friction near-wellbore

After years of practice in hydraulic fracturing, it has been observed that the actual treatment pressure is often higher than the predicted pressure. Subsequent research has identified that hydraulic fracture initiation and propagation near the wellbore, as well as the multi-fracture effect at the fracture end, are key factors influencing the calculated pressure during minor fracture stimulation49,50. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to three causes in the vicinity of the well.

-

(1)

Perforation phase mismatch.

The angle of perforation phase has a significant impact on hydraulic fracture extension. Romero et al. (1995)34 suggested that the included angle between perforation orientation and minimum principal stress should not exceed 10°. Otherwise, it could result in additional stress leading to non-planar or S-shaped fractures, potentially causing hydraulic fracturing failure.

-

(2)

Perforation pressure drop.

The relatively high-pressure drop in the near-wellbore zone can be explained by three additional pressure drops caused by mismatched perforation holes, fracture steering, and perforation orientation.

-

(3)

Fracture bending near-wellbore.

The shape of turning fractures is primarily influenced by treatment displacement, liquid viscosity, and stress ratio (the ratio of maximum principal stress to minimum principal stress). An increase in stress ratio leads to a decrease in bending radius.

The distortion of fractures near the borehole is a result of the complex fracture geometry. A multitude of fractures stem from numerous perforations and micro-fractures51,52,53. The orientation of these adjacent borehole fractures is determined by the existing micro fracture induced by perforation or other means, rather than by the far-field stress orientation that governs the main fracture. As these fractured fractures extend away from the borehole, they eventually realign themselves with the far-field stress orientation. The competition for fracture width space among numerous fractured fractures, combined with their reorientation adjacent to the borehole, results in twisted fractures with particularly narrow widths. The challenge of transporting proppant through these twisted fractures near the wellbore often leads to premature depletion in most fracturing operations, rather than excessive filtration of fracturing fluid or narrow primary fracture width.

Prediction model of fracturing construction pressure

Prediction of the static pressure of wellbore liquid column

In highly deviated wells, the calculation of wellbore hydrostatic pressure is based on the true vertical depth (TVD) of the wellbore. A moving interface model for fracturing fluid is established for any pumping time t, and the wellbore is divided into various physical parameters (such as density ρi, flow rate vi, etc.) for different fluids. The fracturing fluid with identical physical parameters in each section should be subdivided so that the wellbore fluid at time t is divided into several micro sections. This allows for the establishment of the wellbore hydrostatic column pressure at the time of treatment.

Ph — Static pressure of wellbore liquid column, MPa. ρi — Calculate the density of sand mixing fluid in the well section, kg/m3. hi — Calculate the vertical length of the well section, m. N — Number of fluid segments with different properties.

As the surface sand ratio changes continuously during the whole fracturing process, the density of sand mixing fluid injected into each section also changes continuously. According to the ground-sand ratio, the density of the sand mixing liquid pumped into each section can be determined. Assume that the ground sand ratio is Cp, the density of proppant and liquid is ρp and ρf, and the density of sand mixing liquid ρm is:

By repeating the above procedure for the entire treatment time, it is possible to determine the variation of the borehole hydrostatic column pressure over time throughout the fracture treatment. The hydrostatic pressure can be accurately calculated by tracking the shift in the fluid density and the position of the fluid increment in each section of the bore.

Prediction of wellbore fluid friction pressure

Based on the prediction method and concept of static pressure within the wellbore fluid column, a predictive model for wellbore fluid friction pressure can be established. The key difference lies in the calculation of friction pressure within the wellbore, which is dependent on changes in measured depth (MD). The wellbore can be segmented into multiple sections, each with varying inclination angles and flow structures. By utilizing the moving interface model of fracturing fluid, physical parameters such as fluid density (ρi) are considered. Additionally, the fluid velocity is calculated within each respective section, ultimately leading to the establishment of the overall wellbore fluid friction pressure at treatment time t.

Where: Pf — The total wellbore friction, MPa. λi — Friction coefficient of well section calculated. Li — Length of well section calculated, m. i — Diameter of well section calculated, m. vi — Fluid velocity of well section calculated, m/s.

Friction coefficient λi is related to fluid Reynolds number and flow pattern. See Appendix A for a specific calculation. If the casing annulus liquid injection method is adopted, Di in formula (6) is the equivalent diameter of the annulus, Di=D2-D1, D1 and D2 are the outer diameters of tubing and the inner diameter of the casing respectively. By repeating the above method in the whole pumping time, the variation of wellbore fluid friction pressure with time in the whole fracturing operation process can be determined.

The above statement presents the determination of fluid friction pressure based on various calculations of the well profile and physical parameter splitting within the fluid motion interface model. There are alternative methods for calculating inner bore friction pressure during treatment. Firstly, the friction pressure of the pre-fluid is utilized to adjust theoretical coefficients in order to obtain the friction pressure of the sand-mixed fluid. Secondly, a friction correction coefficient for the proppant is established based on measured friction pressure in the lead fluid stage, which then determines the friction pressure of the sand-mixed fluid. The current friction correction coefficients are depicted in Fig. 3. Friction in base fluid (lead fluid) arises from fluid rheology and flow rate, both of which significantly impact wellbore friction pressure. Even under identical trapping conditions, different base fluid frictions result in distinct construction pressure curves.

Analysis of frictional pressure drop in the borehole and near wellbore

Perforation and near-wellbore friction are the primary causes of abnormal construction pressure. This phenomenon can be explained by considering that the pressure drop near the wellbore (total additional pressure) is comprised of perforation friction and near-wellbore friction, which includes friction caused by fracture steering and mismatched perforation orientation:

Ppnwb — Additional pressure in the perforation hole and near the wellbore, MPa. Ppf — Perforation friction pressure, MPa. Ptort — Bending friction pressure near wellbore fracture, MPa.

Analysis of perforation friction

In fracturing operations, the insufficient perforation layer or the blocked perforation hole will lead to a high pressure that the treatment string cannot bear. The distribution of perforations has a great influence on the perforation friction, and the perforation friction is:

Where: ρ — Fracturing fluid density, kg/m3. Q — Pump displacement, m3/min. Dca. — Perforation density, hole /m. d — Diameter of perforation hole, m. h — Effective opening thickness of treatment layer, m. Cd — Orifice discharge coefficient, Dimensionless.

If the fracturing fluid does not contain abrasive materials, Cd is generally 0.5 to 0.6. When the sand-carrying liquid is pumped in, the surface of the hole inside the casing is severely eroded by the sand-carrying liquid, and the flow coefficient of the hole should be corrected, generally rising from 0.52 to 0.90. The currently recommended orifice correction flow coefficients are:

Where Mp is the proppant mass passing through the hole, kg. When Cd ≥ 0.89, Cd = 0.89.

Variations in Cd can considerably affect the size of the perforation hole friction, but in any case, the higher the hole density, the higher the ejection degree, and the lower the hole friction. The larger the diameter of the hole, the smaller the hole friction. At the same time, the aperture size directly affects the proppant size and concentration, and should be large enough to avoid bridging the proppant as it passes through the orifice. If the pore size is too small, the high shear rate will cause the fracturing fluid to degrade as it passes through the pore, which can severely affect the performance of the fracturing fluid and affect the fracturing effect. In addition, the perforation friction is controlled within a reasonable range by controlling the pore density, pore diameter and degree of opening for the purpose of current-limited fracturing.

Bending friction analysis of near wellbore fractures

Factors such as treatment displacement, liquid viscosity, and the ratio of the maximum principal stress to the minimum principal stress (referred to as stress ratio) will all affect the fracture bending shape46. The relationship between stress ratio and fracture bending radius of curvature is:

R — Fracture bending radius, m. KIC — Stress intensity factor, MPa·m0.5. Kr — Stress ratio. σ — Minimum principal stress, MPa.

The friction pressure drop near the wellbore can be expressed as follows39.

Ktort — Near wellbore friction coefficient. β — Coefficient, generally 0.5.

Test analysis of borehole and near-wellbore friction

Friction in the zone adjacent to the wellbore, also referred to as adjacent wellbore fracture distortion, is closely associated with the complexity of the fracture initiation phase. The majority of unplanned screen-outs are ascribed to proppant bridge plugs emerging in the areas adjacent to the wellbore. Factors contributing to fracture complexity in these adjacent regions include:

-

(1)

Multiple fractures initiate at pre-existing micro fractures (whether they are natural, borehole-induced, or perforation-induced).

-

(2)

Abrupt transition from the fracture initiation plane to a preferred initiation orientation.

Either of these mechanisms can give rise to insufficient fracture width in the adjacent wellbore region, potentially causing proppant plugging. During fracturing operations, continuous damage or erosion of perforations takes place simultaneously, leading to variations in their flow coefficients and influencing friction in the surrounding wellbore area due to factors such as injection displacement, frac fluid viscosity, and volume. This may result in the formation of complex fractures like flexures and subsequently complicate theoretical calculations for borehole and near-borehole friction. Two commonly adopted experimental approaches for addressing this issue are displacement step-down and displacement mutation experiments. These experimental results enable precise analysis of perforation hole size and near-bore friction.

Test of displacement step-down

Perforation friction and friction in adjacent wellbore regions can be analytically distinguished due to their different correlations with injection displacement. The perforated bore friction varies as the square of the injection displacement, while the friction in the vicinity of the bore varies roughly as the square root of the injection displacement, owing to flow in the orifice portion. This distinction forms the basis of the displacement step-down test. The displacement step-down test effectively distinguishes between perforated bore friction and friction due to fracture distortion in adjacent bore areas, providing more certain and useful information than the displacement abrupt change test. It is one of the most common techniques for characterization. By applying a least-squares principle based on a series of time, displacement, and friction pressure drop measurements, we first adapt data from the displacement step-down test to an independent power-law equation:

Where, ΔPtef — Fracture entrance friction, including borehole and near-wellbore friction, MPa. Ktotal — Fracture entrance friction coefficient.

In the context of inlet friction in fracturing fractures, when perforation friction is dominant, the β value typically hovers around 2. Conversely, if friction in the region adjacent to the wellbore is predominant, then generally the beta value will be closer to 0.5. By fitting data from displacement step-down tests to the following equation, it becomes possible to differentiate between friction in the perforation hole and friction in the area adjacent to the wellbore.

The only way to differentiate between friction in the adjacent bore area and friction in the perforated bore is by determining the displacement dependence of the measured friction pressure from a displacement step-down test. It is often recommended to conclude all injection phases with a displacement step, as friction in the perforated and adjacent borehole areas typically varies throughout the injection diagnostic pump sequence and fracture treatment pump sequence.

The displacement dependence of friction pressure can only be determined based on the displacement step-down test, rather than relying on instantaneous pump stop pressure that shuts down all pump trucks (for example, during pre-fluid injection after diagnosis or after completion of fracturing operations). To obtain accurate data, it is essential for a step-down test to include at least three injection phases with different displacements, spanning at least two intermediates between full injection displacement and instantaneous pump shutdown pressure. The process involves reducing the ladder’s displacement to 0.

It is not essential to obtain the exact displacement value during each step-down, but it is critical to change as quickly as possible between each displacement and to obtain it as steadily as possible during the short period of displacement values. This can be achieved most easily by shutting down the individual pump trucks for each displacement step. The total displacement step-down time should be minimal compared to the total injection time, in order to ensure that the net pressure does not change significantly during the displacement step-down. It is important to note that this may not be feasible when using small volumes of highly-filtered fracturing fluids injected in highly permeable rocks, or when the net pressure changes rapidly due to proppant effects. In such cases, errors are likely to obscure the results of the displacement step-down test. To enhance our ability to distinguish friction between the perforation hole and the area adjacent to the wellbore, smaller displacement changes should be made between the highest and lowest displacements (i.e., from first step-down to last step-down or pump shutdown).

Test of displacement mutation

For the analysis of sudden displacements, it is commonly assumed that the change in fracture inlet friction is solely due to the alteration in friction in the vicinity of the borehole. It is also presumed that the friction of the perforated holes remains constant and does not undergo any changes. Therefore, displacement catastrophe analysis primarily aims to smooth out the shape of the measured net pressure during displacement alterations, while actual (data) displacement step-down tests necessitate breaking down fracture entry friction into perforation hole friction, as well as resistance and friction in the area adjacent to the wellbore.

The analysis of displacement catastrophe produces more accurate results when bottom hole pressure is directly measured. However, if wellbore friction is relatively minimal and falls within reasonable accuracy limits or can be effectively controlled, and if the wellbore friction is known or combined inlet friction significantly outweighs wellbore friction, then displacement mutation analysis using surface pressure data can also yield precise results.

Prediction and diagnosis of fracturing construction pressure

The flow interface model of fracturing fluid in wellbore

During the fracturing process of highly-deviated wells, fracturing fluids with different properties are injected into the wellbore at various times. Owing to the long bore displacement of highly deviated wells, multiple liquids with distinct properties might be present simultaneously in the bore during pumping. To simulate and predict the construction pressure more effectively, it is essential to calculate the fluid motion interfaces of different properties at different moments based on the pumping string structure, time, and rate. We assume continuous interfaces between liquids in each section without mixing, presenting a plug flow. By combining the pipe-string structures and preset pumping procedures, we determine the relationship between the moving front and trailing edge of the fluid in each wellbore section over time to establish a model of the fluid motion interface for fractures.

-

(1)

Establishment of a pipe string structural model.

The string is divided into different lengths and their relative positions based on the structural parameters. For the oil-casing annulus injection method, the pipe string’s structural model must be established according to the change in diameter of the oil pipe and casing, which commonly corresponds to changes in fluid flow rate and state.

-

(2)

Determination of fluid flow rate.

Physical parameters such as fluid density and velocity in different sizes of pipes or in the annulus of the oil jacket are determined based on pumping schedules and the structural model of the pipe string. It should be noted that a change in pump displacement or string diameter leads to corresponding changes in liquid flow rate and even flow regime within the string.

-

(3)

Determination of leading-edge interface and trailing edge interface for each segment of liquid.

Due to the relationship between pumping time and borehole displacement, one or more different types of fluids may be present in the tube or casing annulus simultaneously, with their properties changing over time. In light of these situations, it is necessary to develop leading-edge and trailing-edge interface models for liquid mobility that describe different fluids at any given time, depending on factors such as pipe string structure, pumping time, pumping procedure etc. The length and flow state of liquid in each section can then be used to analyze trap hydrostatic pressure and friction using corresponding computational models. It is important to note that the rheology of the fracturing fluid is involved in the prediction and calculation of the treatment pressure in highly deviated wells. These characteristic parameters are extremely sensitive to changes in temperature. Therefore, the results of the analysis of the temperature field of the well must be combined to more accurately model the pressure of the fracture operation.

Calculation of fracturing construction pressure

Calculation process

According to the above analysis, the process and flow of construction pressure prediction and real-the time analysis during the fracturing of highly deviated wells are shown in Fig. 4.

-

(1)

Inputting data such as well trajectory, well structure, pumping procedure, operation parameters, etc.

-

(2)

Analyzing wellbore fluid temperature field and establish motion interface models of different fluids at any time.

-

(3)

Calculating of physical parameters and flow state of the fluid in each section.

-

(4)

Treatment pressure prediction analysis.

-

(5)

Repeating steps (2) ~ (4), and predict construction pressure throughout the fracturing process.

Calculation examples and analysis

According to the preset pumping procedure in Table 1, combined with the wellbore trajectory data of the highly deviated well, the relationship curves of wellbore fluid migration interface, hydrostatic pressure, wellbore frictional pressure, and wellbore fluid net pressure during the different pumping processes are obtained, as shown in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. For the convenience of analysis, during the pumping process, the perforation friction and the near-wellbore friction can simply be regarded as variables that do not change much. At the same time, due to the constant change of the inclination angle of the highly deviated well, to explain the influence of the change of the inclination angle on the fluid pressure calculation, it is assumed that the corresponding inclination angle β of the highly deviated well is:

Figure 5 presents the schematic relationship of the migration interface of various fluids in the wellbore during the pumping process. Figure 6 displays the migration front and trailing edges of the sand-carrying fluid 2 (the construction schedule presented in Table 1) at distinct time. The schematic view of the borehole as a function of time, indicating the number of liquid segments injected at different pumping times. During the same pumping period, a wide range of fracturing fluids with different properties exist in the wellbore. This issue is even more prominent in highly deviated wells with long bore displacements. Therefore, attempting to treat the fluid in the entire well as a fluid with uniform properties indiscriminately will result in errors in the prediction of parameters such as the wellbore hydrostatic pressure and the wellbore friction analysis, thereby affecting the accuracy of the prediction of the operating pressure in highly deviated wells.

Figure 7 is a schematic diagram presenting the variation of hydrostatic pressure at diverse inclination angles. As the hydrostatic pressure is computed based on the vertical depth TVD, when the well inclination depth MD is provided, with the increase of the corresponding well inclination angle, the vertical depth TVD of the highly deviated well declines, and the total hydrostatic pressure reduces. As the proppant concentration rises, the liquid density in the wellbore increases, and the total hydrostatic pressure goes up. As the displacement fluid is injected, the density of the wellbore fluid starts to decrease, and the hydrostatic pressure fluid begins to drop. There are numerous types of fluids in the wellbore at different pumping times. Combined with the wellbore fluid migration model, the change of the wellbore hydrostatic pressure with the pumping time can be determined more precisely.

Figure 8 depicts the relationship between trap friction and base fluid friction at a constant trap inclination. An increase in base fluid friction gives rise to higher wellbore fluid friction, while an increase in proppant concentration also elevates wellbore fluid friction. Hence, the abnormal construction pressure curve is not only caused by well bias, but also by the magnitude of base fluid friction. Higher base fluid friction enhances the probability of abnormal pressure at the surface for the same well bias and depth.

Figure 9 illustrates the change in trap net pressure (Pf - Ph) for different trap inclinations with constant base fluid friction. In vertical or directional wells with small inclination angles, increasing proppant concentration leads to a decrease in wellbore fluid net pressure, as shown in Fig. 2. However, in highly deviated wells with larger inclination angles, an increase in proppant concentration causes the wellbore fluid net pressure to trend upward. This trend is more pronounced with higher base fluid friction. Therefore, the relationship between wellbore hydrostatic pressure and wellbore friction differs between highly deviated wells and vertical wells. Attempting to analyze the net wellbore pressure of a highly deviated well using existing vertical well relations will result in significant errors and potentially incorrect conclusions.

Figures 10 and 11 present the curves of friction and welfare net pressure for different base fluids at various trap inclinations. Based on Figs. 9 and 10, it can be observed that the well inclination angle and the base fluid friction will exert a crucial influence on the occurrence of anomalous treatment pressure at the surface. The net pressure of the well fluid ascends with the well inclination and the base fluid friction. The greater the trap inclination, the smaller is the basal fluid friction that leads to the anomalous surface pressure. Similarly, the larger the base fluid friction, the more frequent the surface treatments occur. The inclination angle of the anomalous pressure is also smaller. The fact that the magnitude of the base fluid friction depends on the properties of the well-bore fluid and the state of motion of the fluid also implies the necessity of establishing the well-bore fluid mobility interface from another perspective.

Conclusions

This study examines the variations in fracturing construction pressure of highly deviated well with high inclination angles, along with the factors that give rise to this anomaly. It elucidates the disparities in fracturing construction pressure among horizontal wells, vertical wells, and highly deviated wells. By integrating the well trajectory, fracture string structure, and the fracturing flow process of the horizontal well, a model has been developed to predict the fluid movement interface in each section of the wellbore fracture for horizontal wells. This model offers a theoretical foundation and explanation for the real-time diagnosis of fracturing fracture in the highly deviated well hydraulic fracturing operation.

-

(1)

The pumping pressure and wellbore friction during the fracturing of highly deviated wells are closely associated with the wellbore trajectory, inclination, operational conditions, and other factors. By integrating these effects, a relatively precise model of the interface between the fracturing fluid and borehole motion can be established to predict the relationship between the pumping pressure and borehole frictional resistance.

-

(2)

The complex fracturing stress field in highly deviated wells demands appropriate management to prevent fracture steering or bending, as well as an increase in friction pressure near complex fractures. The technique of reduction and sudden displacement is an accurate approach for predicting puncture and near-bore friction. Combined with the analysis of measured data, this prediction renders the analytical results more realistic and reliable.

-

(3)

Well inclination and the friction of base fluid have a significant impact on pumping pressure. The frictional force exerted on the base fluid is directly related to its properties and motion state, which is of crucial importance for modeling fluid flow interfaces. The rheological parameters of fracturing fluid are highly susceptible to temperature variations, so integrating trap temperature field calculations is indispensable for accurately predicting fracture pressure in highly deviated traps.

-

(4)

The rheology of fracturing fluids plays a crucial role in predicting and calculating the pump injection pressure for extended reach wells. These characteristic parameters are highly sensitive to temperature variations, so integrating the analysis of well temperature fields is indispensable for more accurate modeling of fracture operation pressure.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Perkins, T. K. & Kern, L. R. Widths of hydraulic fractures. J. Pet. Tech. (Sept. 1961) 937–949. Trans., AIME, 222.

Nordgren, R. P. Propagation of a vertical hydraulic fracture. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. (Aug 1972). 306-3 14; Trans., AIME, 253.

Nolte, K. G. Determination of fracture parameters from fracturing pressure decline, paper SPE 8341 presented at 54th Annual Technical Conference, Las Vegas, Sept. 1 979.

Nolte, K. G. & Smith, M. B. Interpretation of fracturing pressures. J. Pet. Tech. (Sept. 198 1) 1, 767–1775.

Hannah, R. R., Harrington, L. J. & Lance, L. C. The real-time calculation of accurate bottomhole fracturing pressure from surface measurements using measured pressures as a base. SPE12062, presented at the 58th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition held in San Francisco, CA, October 5–8, 1983.

Zhuang, L. et al. Laboratory true Triaxial Hydraulic Fracturing of Granite under Six Fluid Injection Schemes and grain-scale Fracture Observations. (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020).

huang, L. et al. Cyclic hydraulic fracturing of puncheon granite cores and its impact on breakdown pressure, acoustic emission amplitudes and injectivity. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 122, 1–9 (2019).

Patel, S. M., Sondergeld, C. H. & Rai, C. S. Laboratory studies of hydraulic fracturing by cyclic injection. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 95, 8–15 (2017).

Hou, B. et al. Characteristics of fracture propagation in compact limestone formation by hydraulic fracturing in central Sichuan, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 57, 122–134 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. A laboratory study of multiple fracture initiation from perforation clusters by cyclic pumping. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(3), 827–840 (2019).

Mingwei Wang, W., Zhou, S., Li & Wu, W. Simulated investigation in wormhole expansion law of gelling acid etching and its influencing factors in deep carbonate reservoirs. Gels 8, 8:470. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8080470 (2022).

Yang Wang, J., Yang, T., Wang, Q., Lv, H. Z. & He, T. Visualization experiment of multi-stage alternating injection acid fracturing, Energy reports, 8, 9094–9103. (2022).

Jordan, C., Debotyam, M. & Iraj, S. Variable pump rate fracturing leads to improved production in the Marcellus shale, in Proceedings of the Texas USA: SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, ‘e Woodlands, TX, USA, February 2016.

Lu, P. et al. Modeling and parameters analysis on a pulsating hydro-fracturing stress disturbance in a coal seam. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 26, 253–263 (2015).

Yoon, J. S., Zimmermann, G. & Zang, A. Numerical investigation on stress shadowing in fluid injection-induced fracture propagation in naturally fractured geothermal reservoirs. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48(4), 1439–1454 (2015).

Tong, S., Gao, E., Feng, Y. & Chen, X. Mechanical principles of hydraulic pressure vibration method for improving hydraulic fracturing treatments a new approach, in Proceedings of the Washington USA: the 52nd US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Seattle, WA, USA, June 2018.

Ge Zhu and Shimin Dong. Simulation model of bottom hole dynamic pressure and reservoir dynamic stress in hydraulic fracturing with pulse injection. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020 Article ID 2906973, 13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2906973.

Pucknell, J. K., Mason, J. N. E. & Vervest, E. G. An evaluation of recent mechanistic models of multiphase flow for predicting pressure drops in oil and gas wells. In: Offshore Europe. Society of Petroleum Engineers. (1993).

Takacs, G. Considerations on the selection of an optimum vertical multiphase pressure drop prediction model for oil wells. In: SPE/ICoTA Coiled Tubing Roundtable. Society of Petroleum Engineers (2001).

Ansari, A. M., Sylvester, N. D., Sarica, C., Shoham, O. & Brill, J. P. A comprehensive mechanistic model for upward two-phase flow in wellbores. SPE Prod. Facil. 9(02), 143–151 (1994).

Chokshi, R. N., Schmidt, Z. & Doty, D. R. Experimental study and the development of a mechanistic model for two-phase flow through vertical tubing. In: SPE Western Regional Meeting. Society of Petroleum Engineers (1996).

Gomez, L. E. et al. A unified mechanistic model for steady-state two-phase flow in wellbores and pipelines. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. OnePetro. (1999).

Zhang, X., Liu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Optimizing the design of horizontal well trajectories for hydraulic fracturing using artificial neural networks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 110870 (2021).

Li, Y., Zhang, X. & Zhang, Y. Optimizing the design of horizontal well trajectories for hydraulic fracturing using genetic algorithms. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 110871 (2021).

Wang, X., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Optimizing the design of horizontal well trajectories for hydraulic fracturing using particle swarm optimization. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 110872 (2021).

Li, Y., Zhang, X. & Zhang, Y. Optimizing the design of horizontal well trajectories for hydraulic fracturing using differential evolution. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 110873 (2021).

Zhang, M., Liu, Z., Jiang, Q. & He, B. Influence of natural caves on hydraulic fracturing pressure curves: numerical modelling and ANNs. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1–22 (2021).

Mukherjee, H. & Brill, J. P. Pressure drop correlations for inclined two-phase flow. J. Energy Resource Technol. 107(115), 549. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3231233 (1985).

Li, D., You, S., Liao, Q., Sheng, M. & Tian, S. Prediction of shale gas production by hydraulic fracturing in Changning area using machine learning algorithms. Transp. Porous Media 149(1), 373–388 (2023).

Kabir, C. S. & Hasan, A. R. A study of multiphase flow behavior in vertical oil wells: part II-field application. In: SPE California Regional Meeting. Soc. Petrol. Eng. (1986).

Maren, A. J. Introduction to neural networks. In: (eds Maren, A. J., Harston, C. T. & Pap, R. M.) Handbook of Neural Computing Applications. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1–12 (1990).

Luo, Y. et al. Optimization method of hydraulic fracturing design for horizontal shale gas well based on artificial nural network and genetic algorithm. Paper presented at the 56th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, June 2022. https://doi.org/10.56952/ARMA-2022-0364.

Huang, Z., Shimeld, J., Williamson, M. & Katsube, J. Permeability prediction with artificial neural network modeling in the Venture gas field, offshore eastern Canada. Geophysics 61, 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1443970 (1996).

Anifowose, F., Adeniye, S. & Abdulraheem, A. Recent advances in the application of computational intelligence techniques in oil and gas reservoir characterization: a comparative study. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 26, 551–570. (2014).

Osman, E-S-A., Ayoub, M. A. & Aggour, M. A. An artificial neural network model for predicting bottom hole flowing pressure in vertical multiphase flow. In: SPE Middle East oil and gas show and conference. Soc. Petrol. Eng. (2005).

Jahanandish, I., Salimifard, B. & Jalalifar, H. Predicting bottom hole pressure in vertical multiphase flowing wells using artificial neural networks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 75, 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2010.11.019 (2011).

Ebrahimi, A. & Khamehchi, E. A robust model for computing pressure drop in vertical multiphase flow. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 26, 1306–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.08.036 (2015).

Awadalla, M. & Yousef, H. Neural networks for flow bottom hole pressure prediction. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 6, 1839. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v6i4.10774 (2016).

Zeeshan Tariq, M., Mahmoud, A. & Abdulraheem Real-time prognosis of flowing bottomhole pressure in a vertical well for a multiphase flow using computational intelligence techniques. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-019-0728-4 (2019).

Li, Y., Peng, G., Du, T., Jiang, L. & Kong, X. Z. Advancing fractured geothermal system modeling with artificial neural network and bidirectional gated recurrent unit. Appl. Energy 372, 123826 (2024).

Abdulwarith, A., Ammar, M., Kakadjian, S., McLaughlin, N. & Dindoruk, B. A hybrid physics augmented predictive model for friction pressure loss in hydraulic fracturing process based on experimental and field data. In: Offshore Technology Conference (p. D031S030R006). OTC. (2024).

Muther, T., Syed, F. I., Dahaghi, A. K., Negahban, S. & September 3, Socio-inspired multi-cohort intelligence and teaching-learning-based optimization for hydraulic fracturing parameters design in tight formations. ASME. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 144(7): 073201. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4052182 (2021).

Bilden, Spearman, H. G. Hudson. Analysis of observed friction pressures recorded while fracturing in highly deviated wellbores. SPE 25492, prepared for presentation at the Production Operations Symposium held in Oklahoma City, OK, U.S.A., March 21–23, (1993).

Romero, J., Mack, M. G. & Elbel, J. L. October. Theoretical model and numerical investigation of near-wellbore effects in hydraulic fracturing. SPE63009, prepared for presentation at the SPE Annual Conference & Exhibition held in Dallas, U.S.A., 22·25 (1995).

Lietard, O. & Hegemen, P. November. Optimum development of a thin box-shaped reservoir with multiply fractured horizontal wells. SPE50420, prepared for presentation at the 1998 SPE International Conference on Horizontal Well Technology held in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 1–4 (1998).

Keck, R., Doris, F. & Reiteretal Analysis of measured bottomhole treating pressures during fracturing: Do not believe those calculated bottomhole pressures. SPE 63033, prepared for presentation at the. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition held in Dallas, Texas, 1–4 October 2000. (2000).

Vibhas, J. Pandey. Friction Pressure Correlation for guar-based Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids. SPE71074.

Hossain, M. M., Rahman, M. K. & Rahman, S. S. April. A comprehensive monograph for hydraulic fracture initiation from deviated wellbores under arbitrary stress regimes. SPE 54360, prepared for presentation at the 1999 SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition held in Jakarta, Indonesia, 20–22 (1999).

Hossain, M. M. & Rahman, M. K. Hydraulic fracture initiation and propagation: roles of wellbore trajectory, perforation, and stress regimes. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 27, 129–149 (2000).

Deeg, W. F. J. High propagation pressures in transverse hydraulic fractures: cause, effect, and remediation. SPE56598, prepared for presentation at the 1999 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition held in Houston, Texas, Oct. 3–6.

H.Gu, J. L. Elbel. Computer simulation of multilayer hydraulic fractures. SPE64789, prepared for presentation at the SPE International Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition in China held in Beijing, China, 7–10 November (2000).

Elbel, J. L. & Piggott, A. Numerical modeling of multilayer fracture treatments. SPE23982, prepared for presentation at the 1992 SPE Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference held in Midland, Texas, March 16–20, (1992).

Romero, J., Mack, M. G. & Elbel, J. L. October. Theoretical model and numerical investigation of near-wellbore effects in hydraulic fracturing. SPE30506, prepared for presentation at the SPE Annual Conference & Exhibition held in Dallas, U.S.A., 22·25 (1995).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to reviewers and editors for their careful review of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFE0206800) and Northeast Petroleum University Youth Fund (Grant No. 2019QNL-01). We are grateful to FAPS Energy Technology Ltd. (www.faps.com.cn) for the use of FAPSeal 3D software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoling Zhang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, and Software. Lingdong Meng and Song li: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, writing — original draft and Writing — review and editing. Kun Yan: Project administration, Resources. Yejun Jin: Investigation, Methodology, Software and Visualization. Ziyang Li: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology. Hailong Fu: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A calculation of friction coefficient of wellbore fracturing fluid

Appendix A calculation of friction coefficient of wellbore fracturing fluid

To calculate the frictional resistance pressure of fracturing fluid flow in the wellbore by using the main text formula (6), λ (the resistance coefficient along the wellbore) must be determined first.

A1 Calculation of friction coefficient of Newtonian fracturing fluid

Newtonian fluid flow friction is related to the fluid flow state, and the fluid flow state is determined according to the Reynolds number:

If NRe ≤ 2100, the fluid flow is laminar, and the coefficient of friction is

If NRe > 2100, the fluid flow is turbulent, and the coefficient of friction is:

Where: NRe — Reynolds number, dimensionless. µ — Fracturing fluid viscosity, mPa·s. v — Fluid velocity in the column, m/s. D — String diameter, m. ρ — Fracturing fluid density, kg/m3.

A2 Calculation of friction coefficient of power-law fracturing fluid

Generally, most of the fracturing fluids are power-law liquids, and the apparent viscosity µa of fracturing fluid flowing in the pipe string can be used to replace µa Newton’s fluid formula, that is,

Ka — Consistency coefficient of fracturing fluid flowing in the wellbore, kg·sn/m2. n — Rheological index of fracturing fluid.

The oil-casing annulus injection method is adopted. In formula (A4), D is the equivalent diameter of the annulus, D = D2-D1, and D1 and D2 are the outer diameter of the oil pipe and the inner diameter of the casing, respectively. Regarding the Reynolds number calculation and flow state discrimination of non-Newtonian power-law fluid pipe flow, the calculation method of Newtonian fluid is mostly used at present. When NRea ≤ 2100, fluid flow is laminar; If NRe > 2100, fluid flow is turbulent. The friction coefficient λ values of different flow regimes can be calculated approximately using the circular tube formulas (A2) and (A3), just replace NRe in the formula with NRea.

A3 Calculation of friction coefficient of sand mixing fluid

The soil is mixed with the proppant to form a sand-mixing fluid, and the resistance coefficient of the sand-mixing fluid is larger than that of the sol. Hannah (1983)5 believed that based on the sol resistance coefficient, multiplying a coefficient M is the friction coefficient of the sand mixing liquid λs

M expression for viscoelastic turbulent liquids:

Where: µr、ρr is respectively dimensionless relative viscosity and relative density.

The relative viscosity µr is the ratio of the viscosity of the sand mixing liquid to the viscosity of the sol, and Keck proposed its expression.

Where: φ — volume fraction of support particles. φmax — volume fraction when supporting particles are closely arranged (0.66). γ — fluid shear rate, in the tubing,\(\:\gamma\:=\frac{8u}{D}\), casing annulus \(\:\gamma\:=\frac{12u}{{D}_{2}-{D}_{1}}\).

The relative density ρr of the sand mixing fluid is defined as

Where: ρf、ρp are respectively the densities of the sol and proppant, kg/m3. Cf、Cp are respectively the liquid and proppant concentrations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, L., Zhang, X., Jin, Y. et al. Prediction model and real-time diagnostics of hydraulic fracturing pressure for highly deviated wells in deep oil and gas reservoirs. Sci Rep 15, 3559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88027-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88027-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Thermodynamic modeling hexamethylenetetramine adsorption on sandstone

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Prediction of methane hydrate equilibrium in saline water solutions based on support vector machine and decision tree techniques

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhancing cement properties for oil wells using MgO-PAM nanocomposites

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Robust development of data-driven models for methane and hydrogen mixture solubility in brine

Geomechanics and Geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources (2025)

-

New approach to reduce the uncertainty level of the shear wave velocity prediction by utilizing ensemble model: A case study from Sirt Basin, Libya

Earth Science Informatics (2025)