Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients have varying degrees of cognitive impairment, but the specific pathogenic mechanism is still unclear. Meanwhile, poor compliance with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in OSA prompts better solutions. This study aimed to identify differentially expressed genes between the non-obese OSA patients and healthy controls, and to explore potential biomarkers associated with cognitive impairment. Cohorts of healthy control (n = 20) and non-obese, treatment-naïve OSA patients (n = 20) were recruited. We collected their peripheral blood mononuclear cells and neutrophils, and their cognitive performances were evaluated by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The differentially expressed genes were identified by bioinformatic analysis and confirmed by PCR. Imbalanced immune cell proportions were assessed by Cibersort. Biomarkers related to enriched cellular pathways were measured by ELISA. OSA patients showed a significant decline in overall cognitive function and were associated with higher daytime sleepiness scores. Multiple signaling pathways were enriched in the non-obese OSA cohort, including upregulation of neutrophil-degranulation. Increased monocyte proportion and decreased NK cell proportion were figured out. The relevant genes, including upregulated defensin alpha 4 (DEFA4), haptoglobin (HP), survivin (BIRC5), and suppressed interferon gamma (IFNG) expression were detected. The relative expression of DEFA4 was significantly correlated with the MoCA score and sleep parameters. Biomarkers such as myeloperoxidase (MPO), H2O2, and lipocalin-2, as representatives of neutrophils’ activation, elevated significantly in the OSA group. The data demonstrated a positive correlation between MPO and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and a negative correlation between MPO and lowest oxygen saturation (LSaO2). The level of Lipocalin-2 was positively correlated with apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and ODI and negatively correlated with LSaO2 and MoCA score. We also observed a negative correlation between H2O2 and mean oxygen saturation (MSaO2). Degranulation of neutrophils was activated in non-obese OSA patients without other complications. The process is related to OSA severity and cognitive impairment, implying its role in pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a heterogeneous sleeping disorder attributed to episodic narrowing or collapsing of the upper airway. The vital pathophysiology of OSA encompasses intermittent hypoxia (IH) and sleep fragmentation1. Typical OSA manifests with chest discomfort, breath cessation, and excessive daytime sleepiness. The standard diagnosis of OSA relies on a laboratory test called polysomnography (PSG), which quantifies the nocturnal respiratory events denoted as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). AHI has also been widely applied in OSA severity evaluation2. Although substantially underdiagnosed and undertreated3, the prevalence of mild OSA has been estimated as high as over 80%. With noticeable dominance in the males, inconsistent incidence of OSA was observed among various races, ethnicities, and ages4. As the therapeutic mainstay, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) could guarantee patients’ ventilation by splinting open their airways5. However, unqualified CPAP adherence remained the research focus for a long time without improvement6.

OSA predisposed patients to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic, arrhythmic, chronic pulmonary, renal, neuropsychiatric comorbidities, and therapeutic resistance7. Due to insufficient CPAP usage, the enhancement of long-term clinical outcomes was thwarted8. Meanwhile, the detailed pathogenesis of OSA has been investigated to explore more potential therapeutic targets. Inflammation ignited by oxidative stress played a significant role in OSA pathogenesis9. A robust deconvoluted algorithm, known as Cibersort, has been developed to “enumerate” immune cell subgroups based on transcriptional data10,11. It aided in profiling the underlying inflammatory disturbance in discrepant scenarios12,13,14.

Recent evidence indicated that alterations in inflammation markers and immune cell populations could initiate or exacerbate neuroinflammation and perpetuate the neurodegenerative process15,16,17. IH-induced peripheral inflammation can cause glial cell activation, neuronal death, and neuroinflammation in the central nervous system via blood-brain barrier damage or vagal afferent18. Hypoxia influences the phenotype and proportion of immune cells, which promotes inflammation19. However, whether alterations in immune cells are associated with cognitive decline in OSA remains unclear.

Herein, we analyzed dysregulated pathways and inflammation-related features originating from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) RNA transcripts of healthy controls and non-obese OSA patients. Public datasets have validated the influence of CPAP on these pathways. In addition, hub genes and their relations to clinical phenotypes were identified and verified, which indicated plausible biomarkers and druggable targets for future investigations.

Methods

Study population

This study enrolled 20 healthy controls and 20 OSA patients recruited from the Sleep Center of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. All the volunteers received PSG, and basic information such as age, BMI, education level, blood pressure, medical history, and medication history were recorded. Only male participants of 18 to 65 years old were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were described as (a) infection, asthma attack, trauma, vaccination, dental therapy during the past month; (b) operation within three months; (c) BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2; (d) with the listed comorbidities: hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung diseases, hyperlipidemia, nervous system disease, and other chronic conditions; (e) current cigarette smokers and those who ceased smoking within one year; (f) chronic medication intake. The subjects with AHI less than 5/hour have been assigned to the “healthy control” group, and those with AHI over 15/hour have been assigned to the “OSA patient” group. All subjects agreed to participate in this study and signed informed consent. General clinical information of all participants was collected, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), educational level, and smoking index (= number of cigarettes smoked per day × years of smoking).

Assessment of daytime sleepiness and cognitive function

The Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) was used to assess daytime sleepiness in the subjects. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to assess the general cognitive function.

Sleep data acquisition

All subjects underwent full-night PSG (Alice LDE, Philips, USA) in the sleep medicine center or wore the portable sleep monitor (NOX T3, ResMed, USA) at home from 10:00 pm to 6:00 am. Cessation of airflow ≥ 10 s was defined as apnea, and reduction in airflow by at least 30% ≥10 s with decreased oxygen saturation (a decrease of at least 4%) was defined as hypopnea20. The AHI was computed by dividing the total number of apneas and hypopneas by total sleep time. OSA was defined when the apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5 events/hour.

Peripheral blood cell separation

All the subjects were asked to avoid drinking alcohol, strong tea, or coffee within 24 h. 10 ml fasting venous blood (fasting period ≥ 8 h) was collected with EDTA anticoagulation tubes and separating glue/coagulant tubes from subjects in the morning. 5 ml of peripheral blood collected in an EDTA anticoagulation tube was diluted with the same volume of 1×PBS solution). We used the lymphocyte separation medium (TBDscience, LTS1077) to isolate PBMC by density gradient centrifugation, and used human peripheral blood neutrophil isolation solution kit (TBDscience, LZS11131) to isolate neutrophils.

Online data collection

The public data matrix was downloaded online from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The selected studies included treatment-naïve OSA patients and patients with adequate CPAP treatment. The specimens for sequencing were obtained from peripheral blood, and gene expression profiles were detected in an array. The GSE49800 dataset contained transcriptional information from peripheral blood leukocytes. The GSE75097 dataset and the GSE133601 dataset contained transcriptional information from PBMC.

Transcriptome sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from PBMC and neutrophils using Trizol reagent, and the quality was controlled by concentration and optical density value. The RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina platform.

Evaluate the proportion of immune cells

The Cibersort is a deconvolution algorithm developed for calculating the relative abundance of 22 immune cell types based on their molecular features. Cibersort estimated the discrepancy of immune cell proportions in peripheral blood between the controls and OSA patients. LM22 signatures were applied as algorithmic patterns, and the results were satisfied with a P value < 0.05. For each sample, all the immune cell fractions added up to 1.

Differential expression analysis and enrichment analysis

The deseq2 R package was applied to discern differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The adjusted P-value was corrected by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) and was set as the threshold for statistical significance. DEGs were identified with expression fold changes above 1.5 and adjusted P value below 0.05 within comparison between the healthy control and OSA patient groups. A heatmap of top-upregulated and downregulated DEGs was generated by R software.

The online data was processed by Robust Multiarray Average by limma R package. The genes with zero expression in over 50% of the samples were excluded from further analysis.

In terms of biological functions, analysis was conducted using critical modules of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways21. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) is a method that illustrates the phenotypes by attributing them to gene distribution trends in the priori-defined sets. To further investigate the enriched pathway, single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was performed to assess the level of pathway (recorded as ssGSEA score) for each sample according to the gene expression levels in corresponding pathways. The enrichment analysis of function was accomplished using the clusterProfiler R package.

Protein-protein interactions and hub genes

The protein interactive network was established through the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) with medium confidence ≥ 0.4 set as the cut-off value. The network was visualized using Cytoscape software, and the pivotal hub genes were selected for the following validation.

Validation of hub genes and biomarkers

The mRNA levels were detected using the 2×Universal Blue SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix Kit (G3326-05, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), and reverse transcription was performed by RevertAid Master Mix Kit (M16315, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, American). All of the primer sequences were listed in Supplementary Table S1. The 2−△△Ct method assessed relative mRNA expression normalized to β-actin mRNA levels.

The other 5 ml peripheral blood collected in a separating glue/coagulant tube was centrifuged at 3000 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min, and the upper serum was collected and frozen at -80 °C. The levels of Lipocalin-2 (KE00144, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), myeloperoxidase (MPO) (KE00171, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and H2O2 (A064-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) in serum were measured by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics 25, R software 4.1, and GraphPad Prism version 8. The quantitative data in this study were represented as mean ± standard deviation, and the qualitative data were expressed as numbers (percentages). Quantitative data was tested using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, while qualitative data was tested using the chi-square test. For correlation analysis, Pearson’s correlation test was performed for quantitative data with normal distribution, while Spearman’s test was performed for quantitative data with abnormal distribution. P value<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features

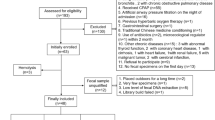

20 OSA patients and 20 healthy controls were enrolled in the study. Age, sex, BMI, smoking index, and years of education were matched between the two groups, and their essential clinical characteristics were shown in Table 1. OSA patients had obviously higher ESS scores (8.80 ± 5.12) and lower MoCA scores (27.00 ± 1.45) compared with the healthy controls (ESS score 2.85 ± 3.54, MoCA score 28.7 ± 0.80). The flow diagram of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

DEGs between OSA and control

We chose 13 OSA patients and 10 healthy controls with no statistically significant differences in age, sex, smoking index, and education (Table 2), and extracted RNA from their PBMC for transcriptome sequencing analysis. By principal component analysis (Fig. 2A), we found a significant separation of PBMC transcript information between the OSA and healthy control groups. The contribution values of Dim 1 and Dim 2 were 33.9% and 17.8%, respectively, indicating that the transcript information of OSA patients was changed to a certain extent. The heat map (Fig. 2B) showed many DEGs in PBMC between OSA patients and healthy controls. We identified 66 DEGs, of which 25 were up-regulated and 41 down-regulated.

Differential expression of biological processes

KEGG and GSEA enrichment analyses were performed to determine the potential biological functions of DEGs. KEGG enrichment analysis showed that DEGs were mainly enriched in antigen processing and presentation, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, graft-versus-host disease, platinum drug resistance, and IL-17 signaling pathways (Fig. 3A). From the results of GSEA enrichment analysis, some pathways, such as the ribosome, hematopoietic cell lineage, asthma, and oxidative phosphorylation pathway, were significantly activated. In contrast, taste transduction, olfactory transduction, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathways, and bile secretion were suppressed (Fig. 3B). At the same time, we noticed that the neutrophil function-related signaling pathways were changed in OSA patients, and the GSEA enrichment plots showed that the expression of neutrophil extracellular trap formation and reactome neutrophil degranulation pathways were significantly increased in OSA patients (Fig. 3C). Respectively enrichment analyses of upregulated DEGs and downregulated DEGs were showed in Figure S1.

Differential expression of biological processes by enrichment analysis. (A) KEGG enrichment analysis displayed the functional pathways in OSA patients that differed from those in healthy controls. (B) OSA-related pathogeneses were found by ssGSEA enrichment analysis. (C) GSEA enrichment analysis suggested alterations in neutrophil-related functions.

DEGs of OSA patients before and after CPAP treatment

We analyzed transcriptional information of OSA patients in 3 GEO datasets, including GSE49800, GSE75097, and GSE133601. All of the OSA patients enrolled in the study had excellent adherence to CPAP therapy. The volcano maps showed DEGs of OSA patients before and after CPAP treatment (Fig. 4). However, there was no significant difference in gene expression before and after CPAP treatment in OSA patients when the adjusted P value (< 0.05) was applied.

Volcano plots of DEGs before and after CPAP treatments in OSA patients. (A) Differential gene expression in leukocytes of OSA patients before (N=18) and after CPAP (N=18) in the GSE49800 dataset (CPAP adherence: 6.9±1.0 h/night in the last two weeks), P<0.05, adjusted P<0.05 (FDR). (B) Differential gene expression in PBMCs of OSA patients before (N=28) and after CPAP (N=14) in the GSE75097 dataset (CPAP adherence>4 h/night in the last year), P<0.05, adjusted P<0.05 (FDR). (C) Differential gene expression in PBMCs of OSA patients before (N=15) and after CPAP (N=15) in the GSE133601 dataset (CPAP adherence>4 h/night in the last 3 months), P<0.05, adjusted P<0.05 (FDR).

Proportion of immune cells

The proportions of immune cells were evaluated by the Cibersort computational methods (Fig. 5). Compared with healthy controls, we found that OSA patients had an increased proportion of monocytes, T regulatory cells, and resting CD4 + T memory cells, and a decreased proportion of resting and activated NK cells. The immune-infiltrating landscape was showed in Figure S2.

Different cell proportions in health controls and OSA patients. Cibersort was used to estimate the proportion of monocytes (A), resting NK cells (B), activated NK cells (C), T regulatory cells (D), and resting CD4+T memory cells (E) in healthy controls (N=10) and OSA patients (N=13), P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Protein-protein interactions network and neutrophil degranulation-related hub genes

The protein-protein interactions network and hub genes are shown in Fig. 6A. Moreover, we verified the up-regulation of defensin alpha 4 (DEFA4), haptoglobin (HP), survivin (BIRC5), while the down-regulation of interferon gamma (IFNG) by qPCR in the PBMC of OSA patients (Fig. 6B). Notably, we also found that the relative expression of DEFA4 was significantly correlated with MoCA score (R=-0.580, P = 0.041) and sleep parameters including AHI (R = 0.636, P = 0.022), ODI (R = 0.582, P = 0.040), LSaO2 (R=-0.803, P = 0.002), and MSaO2 (R=-0.624, P = 0.025) (Fig. 6C). In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between the relative expression of IFNG and MSaO2 (R=-0.644, P = 0.020).

Identification of hub DEGs and correlation analysis in OSA patients. (A) PPI network and hub genes (red represents up-regulated DEGs, and blue represents down-regulated DEGs in OSA patients compared to healthy controls). (B) Verification of neutrophil degranulation-related hub genes in OSA patients (N=13) and healthy controls (N=10). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (C) Relationships between sleep parameters, MoCA score and neutrophil degranulation-related hub genes in OSA patients (N=13), P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Serum markers associated with neutrophil degranulation increased

We used ELISA to detect related biomarkers further to verify the possibility of neutrophil degranulation in OSA patients. We found that serum levels of Lipocalin-2, MPO, and H2O2 were greatly increased in OSA patients (Fig. 7A). Correlation analyses were performed to describe the relationship between sleep parameters, cognitive decline and the serum level of neutrophil degranulation markers (Fig. 7B). The level of Lipocalin-2 was positively correlated with AHI (R = 0.693, P<0.001), ODI (R = 0.743, P<0.001), but negatively correlated with LSaO2 (R=-0.527, P = 0.017) and MoCA score (R=-0.544, P = 0.013). The level of MPO was positively correlated with ODI (R = 0.466, P = 0.038) while negatively correlated with LSaO2 (R=-0.569, P = 0.009). Moreover, the level of H2O2 was negatively correlated with MSaO2 (R=-0.478, P = 0.033).

Serum markers of neutrophil degranulation and correlation analysis in OSA patients. (A) Serum levels of Lipocalin-2, MPO, and H2O2 in healthy controls (N=20) and OSA patients (N=20), *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (B) Relationships between sleep parameters, MoCA score and serum markers of neutrophil degranulation in OSA patients (N=20), P<0.05.

Validation of the neutrophil degranulation-related hub genes in neutrophils of OSA patients

To further verify the results of the study, we re-collected the peripheral blood of 6 OSA patients and 6 healthy controls in this study and isolated their neutrophils. Similar to the expression in PBMC, DEFA4, HP, and BIRC5 were up-regulated whereas IFNG was down-regulated in the neutrophils of OSA patients compared with healthy controls (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Systemic inflammation, attested in several studies, has been incorporated as a piece of the pathogenesis of OSA. The typical circulating biomarkers were partially correlated with AHI, among which the skewed ratio of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets showed significant differences between OSA patients with graded severities22,23, except for distinct pro-inflammatory mediators24,25. A similar imbalance of assorted immune cell proportions was also noticed in this study. Analogous-activated inflammation pathways were also reported based on analysis in OSA patients26.

Neutrophils function as primary responders in innate immunity to pro-inflammatory stimuli. The neutrophils’ dysfunction, including degranulation and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), has been noticed. Several procedures are involved in neutrophils’ activation and motivation27,28, where “degranulation” is defined as a highly-regulated exocytosis process that deploys constituent proteins to secret granules29,30. These granules were previously supposed to defend against infection and later dynamic participants in chronic or unresolved inflammation28,31. IH promotes oxidative stress by increased production of reactive oxygen species, sympathetic activation, and systemic and vascular inflammation, which contributes to diverse multiorgan impairments, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysfunction, cognitive decline, and progression of cancer32. IH, the central pathophysiology of OSA, could also serve as a trigger of the processes mentioned above. A few pieces of evidence already corroborated that hypoxic treatment led to prolonged survival and stimulated phenotype of neutrophils33,34 as well as enhanced degranulation and NETs formation35,36. However, the possible contribution of these molecular pathologies to comorbidities of OSA needs further exploration. Neutrophil-driven inflammation has been recognized as a common mechanism for many pathological conditions, and the release of granulocytes into the extracellular environment can cause damage to surrounding tissues and prolong the inflammatory response31. Peripheral inflammation can trigger neuroinflammation in the central nervous system by damaging the blood-brain barrier or stimulating the vagus nerve in OSA18. Besides, neutrophil infiltration and NETs formation may contribute to neurocognitive impairment by damaging the blood-brain barrier and activating microglia37. Besides, other enriched pathways indicating relevant links between OSA and potential complications called for more detailed research. The protein expression of neutrophils changes during maturation, resulting in the formation of different subtypes of granules.

Certain archetypal proteins could distinguish the different particle subtypes, and some of them, such as MPO and lipocalin-2, were markers of neutrophil degranulation38,39. MPO was a member of the heme peroxidase-cyclooxygenase superfamily and was expressed mainly in neutrophils, which was considered a target for regulating and treating neutrophil function40. Lipocalin-2 belonged to the lipid carrier protein superfamily, and the primary source of plasma lipocalin-2 was neutrophils39. A recent study found that platelet serotonin promoted neutrophil degranulation, increased MPO and H2O2 secretion, and aggravated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury41. H2O2 was a highly active oxidative burst product closely related to the activation of neutrophils42. Meanwhile, serum biomarkers of OSA patients related to neutrophil degranulation were significantly increased in this study. This suggested that activation and degranulation of neutrophils might occur in peripheral circulation in OSA patients. In addition, we found cognitive scores and sleep parameters correlated with these markers in OSA patients.

Suppressed NK cell counts and Interferon gamma (IFN γ) levels in parallel with up-regulated infiltration of T cell subgroups were also detected in non-obese OSA patients compared to health controls. Natural killer cells (NK cells), the crucial producer of IFN γ, work as the sentinel defenders, endowed with other versatile responsibilities43. Except for their dominance in fighting viral infections and tumor cells, NK cells also regulated the activities of several major innate immunity subsets44. NK cells might exert restraint and surveillance on the intrinsic or adaptive immunity, thus contributing to the control of over-reactive autoimmunity45,46. Notwithstanding, the intricate interactions between these immune cell groups remain obscure. Previous studies have reported that the proportion of NK cells was elevated in OSA patients and was more pronounced in patients with metabolic syndrome, more than half of OSA patients had obesity or metabolic syndrome might account for the difference in results47. DEFA4 encodes defensin alpha 4, which is identified as a short antibacterial peptide released by neutrophils48. Defensins play an indispensable role in pathogen clearance49 and mediate the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells50. Some fundamental research displayed their involvement in various systemic inflammation-related conditions51,52,53. We noticed elevated DEFA4 transcriptional expression was positively correlated with AHI, which indicates that DEFA4 might promote systemic inflammation derived from stimulated neutrophils. Expression changes of DEFA4 were reported in many neurological disorders and may be a consequence of the inflammatory state in vivo54. Previous studies showed that DEFA4 expression was upregulated in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment55, schizophrenia56, and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease57 compared with controls. The results of this study suggested a negative correlation between DEFA4 expression and MoCA score in OSA patients. The mechanism for this phenomenon remains unclear, we speculate that it may be related to the inflammation induced by intermittent hypoxia.

Under the condition of hypoxia or inflammation, an increased level of BIRC5 often can be detected58. Previous studies have had uncertain results about BIRC5 in OSA. Some researchers found that BIRC5 was reduced in the circulation of OSA patients59. In the hippocampus of the intermittent hypoxic rat model, BIRC5 increased initially and then decreased with time60. Our PCR result of BIRC5 is not consistent with circulating levels mentioned in previous studies, probably because the inclusion criteria and severity of the disease are different. The protein product of the BIRC5 gene is survivin, a member of the apoptosis inhibitor protein family61,62. Survivin was reported to play an essential role in regulating neutrophil apoptosis. It is highly expressed in immature neutrophils, which proliferate during differentiation. However, mature neutrophils contain little or no survivin protein, and these cells re-express survivin under inflammatory conditions in response to granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor stimulation63. Recent studies have suggested that neutrophil apoptosis can further trigger NETosis64. Elevated plasma HP level is often found in patients suffering from infection, inflammation, and various malignant diseases due to its acute-phase nature and ability to remove oxidative species from the circulation. In addition, HP can specifically combine with hemoglobin and stimulate the monocyte/macrophage lineage65. Previous studies had detected an increase in serum HP in OSA patients and found that its level was independently correlated with the AHI66, and this is consistent with the trend of our PCR result. Another study showed no significant differences in haptoglobin concentrations between OSA patients and controls67. In addition, the phenotype of haptoglobin was reported to be an essential risk factor in determining susceptibility to cardiovascular disease in OSA68. However, data from the Sleep Heart Health Study suggested there was no similar association between haptoglobin phenotype and prevalent cardiovascular disease in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. The authors thought that the differences in conclusions might be due to different selection and older age of study subjects69.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been referred to as “the gold standard therapy”2,70 currently for managing moderate-to-severe OSA. CPAP stabilizes cyclical airway pressure swings by bracing the lumen structure71. Substantial improvements in daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and inconsistent normalization of measurements about complications have been testified in OSA patients under CPAP therapy72. However, the CPAP regimen was restricted by qualified adherence6,73. In addition, the general cognitive function of OSA patients declined, which was consistent with previous studies74,75. As the primary treatment for OSA patients, CPAP could partly improve cognitive function but required patients to adhere to standard treatment for the long term76, which was contrained by poor clinical compliance. In this study, no significant improvement in the dysregulated mediators was found, indicating that the therapeutic effect of CPAP on OSA was limited. More attention should be paid to the requirement for additional treatments beyond the “one-fits-all” strategy.

We are aware of the limitations of our research. First of all, the sample size of this study was small. To avoid bias, candidates in this study with the commonly seen comorbidities of OSA were excluded. Secondly, most of the findings in this study were obtained from PBMC samples of OSA patients, so further verification and deeper exploration from the perspective of neutrophils are required to confirm the connection between neutrophil degranulation and cognitive impairment in OSA patients.

Conclusion

Comparison of PBMC transcriptional profile between the health controls and the non-obese middle-aged OSA patients revealed several dysfunctional inflammation-related pathways. The pathological process with neutrophil participation, especially degranulation, and corresponding potential regulators such as DEFA4, IFNG, HP, and BIRC5 have been identified and validated as well as their correlations to clinical parameters. However, further investigations are needed to explore the involvement of relative pathways in different subgroup OSA patients and their changes after a well-adhered CPAP regimen.

Data availability

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive67 (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021) in National Genomics Data Center68 (Nucleic Acids Res 2022), China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA-Human: HRA008044) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human.

Change history

17 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27943-5

References

Patel, S. R. Obstructive sleep apnea. Ann. Intern. Med. 171 Itc81–itc96 (2019).

Jordan, A. S., McSharry, D. G. & Malhotra, A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet 383, 736–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60734-5 (2014).

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30198-5 (2019).

Lyons, M. M., Bhatt, N. Y., Pack, A. I. & Magalang, U. J. Global burden of sleep-disordered breathing and its implications. Respirol. (Carlton Vic). 25, 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13838 (2020).

Greenstone, M. & Hack, M. Obstructive sleep apnoea. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed.). 348, g3745. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3745 (2014).

Bakker, J. P., Weaver, T. E., Parthasarathy, S. & Aloia, M. S. Adherence to CPAP: What should we be Aiming for, and how can we get there? Chest 155, 1272–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.01.012 (2019).

McNicholas, W. T. Obstructive sleep apnoea and comorbidity - an overview of the association and impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 13, 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2019.1575204 (2019).

Xia, F. & Sawan, M. Clinical and research solutions to manage obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sensor (Basel Switzerland). 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/s21051784 (2021).

May, A. M. & Mehra, R. Obstructive sleep apnea: role of intermittent hypoxia and inflammation. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 35, 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1390023 (2014).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Le, T., Aronow, R. A., Kirshtein, A. & Shahriyari, L. A review of digital cytometry methods: estimating the relative abundance of cell types in a bulk of cells. Brief. Bioinform. 22 https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa219 (2021).

Sui, S. et al. An immune cell infiltration-based immune score model predicts prognosis and chemotherapy effects in breast cancer. Theranostics 10, 11938–11949. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.49451 (2020).

Yu, R. et al. Identification of Diagnostic signatures and Immune Cell infiltration characteristics in rheumatoid arthritis by integrating bioinformatic analysis and machine-learning strategies. Front. Immunol. 12, 724934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.724934 (2021).

Xie, Z. et al. Identification and verification of biomarkers and immune infiltration in obesity-related atrial fibrillation. Biology 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12010121 (2023).

Tansey, M. G. et al. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00684-6 (2022).

Zhang, Y. R. et al. Peripheral immunity is associated with the risk of incident dementia. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 1956–1962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01446-5 (2022).

Sæther, L. S. et al. Cognitive and inflammatory heterogeneity in severe mental illness: translating findings from blood to brain. Brain Behav. Immun. 118, 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2024.03.014 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. The relationship between inflammation and neurocognitive dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J. Neuroinflammation. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01905-2 (2020).

Mirchandani, A. S. et al. Hypoxia shapes the immune landscape in lung injury and promotes the persistence of inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 23, 927–939. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-022-01216-z (2022).

Jonas, D. E. et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 317, 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19635 (2017).

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html

Altintas, N. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in obstructive sleep apnea; a multi center, retrospective study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 3234–3240 (2015).

Topuz, M. F., Ture, N., Akdag, G., Arik, O. & Gulhan, P. Y. The importance of systemic immune-inflammation index in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Soc. (EUFOS) Affil. German Soc. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Head Neck Surg. 279, 5033–5038. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-07227-0 (2022).

Aihara, K. et al. Analysis of systemic and airway inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. Breath. Schlaf Atmung. 17, 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-012-0726-y (2013).

Orrù, G. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, oxidative stress, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction-An overview of predictive laboratory biomarkers. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 6939–6948. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202006_21685 (2020).

Zhu, J., Sanford, L. D., Ren, R., Zhang, Y. & Tang, X. Multiple machine learning methods reveal key biomarkers of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Front. Genet. 13, 927545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.927545 (2022).

Ley, K. et al. Neutrophils: new insights and open questions. Sci. Immunol. 3 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aat4579 (2018).

Mayadas, T. N., Cullere, X. & Lowell, C. A. The multifaceted functions of neutrophils. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 9, 181–218. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164023 (2014).

Mollinedo, F. Neutrophil degranulation, plasticity, and cancer metastasis. Trends Immunol. 40, 228–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2019.01.006 (2019).

Rosales, C. Neutrophils at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 108, 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlb.4mir0220-574rr (2020).

Othman, A., Sekheri, M. & Filep, J. G. Roles of neutrophil granule proteins in orchestrating inflammation and immunity. FEBS J. 289, 3932–3953. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15803 (2022).

Dewan, N. A., Nieto, F. J. & Somers, V. K. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA: implications for comorbidities. Chest 147, 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0500 (2015).

Dyugovskaya, L., Polyakov, A., Lavie, P. & Lavie, L. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis in patients with sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 177, 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200705-675OC (2008).

Dyugovskaya, L., Polyakov, A., Ginsberg, D., Lavie, P. & Lavie, L. Molecular pathways of spontaneous and TNF-{alpha}-mediated neutrophil apoptosis under intermittent hypoxia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 45, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2010-0025OC (2011).

Hoenderdos, K. et al. Hypoxia upregulates neutrophil degranulation and potential for tissue injury. Thorax 71, 1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207604 (2016).

Dölling, M. et al. Hypoxia promotes neutrophil survival after acute myocardial infarction. Front. Immunol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.726153 (2022).

Shafqat, A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in central nervous system pathologies: a mini review. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1083242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1083242 (2023).

Lodge, K. M., Cowburn, A. S., Li, W. & Condliffe, A. M. The impact of Hypoxia on neutrophil degranulation and consequences for the host. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041183 (2020).

Zhang, N., Aiyasiding, X., Li, W. J., Liao, H. H. & Tang, Q. Z. Neutrophil degranulation and myocardial infarction. Cell. Commun. Signal. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-00824-4 (2022).

Rizo-Téllez, S. A., Sekheri, M., Filep, J. G. & Myeloperoxidase Regulation of neutrophil function and target for therapy. Antioxidants (Basel). 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11112302 (2022).

Mauler, M. et al. Platelet serotonin aggravates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via neutrophil degranulation. Circulation 139, 918–931. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033942 (2019).

Winterbourn, C. C., Kettle, A. J. & Hampton, M. B. Reactive oxygen species and neutrophil function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 85, 765–792. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014442 (2016).

Paolini, R., Bernardini, G., Molfetta, R. & Santoni, A. NK cells and interferons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 26, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.11.003 (2015).

Moretta, A., Marcenaro, E., Parolini, S., Ferlazzo, G. & Moretta, L. NK cells at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Cell Death Differ. 15, 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4402170 (2008).

Vivier, E. et al. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science (New York N Y). 331, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198687 (2011).

Lünemann, A., Lünemann, J. D. & Münz, C. Regulatory NK-cell functions in inflammation and autoimmunity. Mol. Med. (Cambridge Mass). 15, 352–358. https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2009.00035 (2009).

Domagała-Kulawik, J., Osińska, I., Piechuta, A., Bielicki, P. & Skirecki, T. T, B, and NKT cells in systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnoea. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 161579. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/161579 (2015).

Lehrer, R. I. & Lu, W. α-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 245, 84–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01082.x (2012).

Chen, H. et al. Recent advances in the research and development of human defensins. Peptides 27, 931–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.08.018 (2006).

Yang, D. et al. Defensin participation in innate and adaptive immunity. Curr. Pharm. Design. 13, 3131–3139. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161207782110453 (2007).

Nassar, H. et al. alpha-Defensin: link between inflammation and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 194, 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.046 (2007).

Sakamoto, N. et al. Association of elevated α-defensin levels with interstitial pneumonia in patients with systemic sclerosis. Respir. Res. 16, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0308-1 (2015).

Joseph, G. et al. Plasma alpha-defensin is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 1 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 1470–1475. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-1910 (2008).

Basingab, F. et al. Alterations in immune-related defensin alpha 4 (DEFA4) gene expression in health and disease. Int. J. Inflam. 9099136 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9099136 (2022).

Cohen, D., Pilozzi, A. & Huang, X. Network medicine approach for analysis of Alzheimer’s disease gene expression data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010332 (2020).

Gardiner, E. J. et al. Gene expression analysis reveals schizophrenia-associated dysregulation of immune pathways in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.007 (2013).

Infante, J. et al. Identification of candidate genes for Parkinson’s disease through blood transcriptome analysis in LRRK2-G2019S carriers, idiopathic cases, and controls. Neurobiol. Aging. 36, 1105–1109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.039 (2015).

Gravina, G. et al. Survivin in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 16, 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.016 (2017).

Kunos, L. et al. Circulating survivin levels in obstructive sleep apnoea. Lung 196, 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-018-0120-z (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Intermittent hypoxia promotes the expressions of rat hippocampal neuronal hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and survivin. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 31, 338–341 (2015).

Rafatmanesh, A. et al. The survivin molecule as a double-edged sword in cellular physiologic and pathologic conditions and its role as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 235, 725–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29027 (2020).

Fäldt Beding, A., Larsson, P., Helou, K., Einbeigi, Z. & Parris, T. Z. Pan-cancer analysis identifies BIRC5 as a prognostic biomarker. BMC Cancer. 22, 322. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09371-0 (2022).

Altznauer, F. et al. Inflammation-associated cell cycle-independent block of apoptosis by survivin in terminally differentiated neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 199, 1343–1354 (2004).

Zhu, Y. P. et al. NET formation is a default epigenetic program controlled by PAD4 in apoptotic neutrophils. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj1397. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj1397 (2023).

di Masi, A. et al. Haptoglobin: from hemoglobin scavenging to human health. Mol. Aspects Med. 73, 100851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2020.100851 (2020).

Kim, J. et al. Increase in serum haptoglobin and apolipoprotein M in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. J. Sleep. Res. 18, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00725.x (2009).

Kiens, O. et al. The effect of obstructive sleep apnea on peripheral blood amino acid and biogenic amine metabolome at multiple time points overnight. Sci. Rep. 11, 10811. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88409-y (2021).

Lavie, L. et al. Haptoglobin polymorphism is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 26, 592–595 (2003).

Levy, A. P. et al. Haptoglobin phenotype, sleep-disordered breathing, and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease: the sleep heart health study. Sleep 28, 207–213 (2005).

Lance, C. G. Positive airway pressure: making an impact on sleep apnea. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 86, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.86.s1.05 (2019).

Hsu, A. A. & Lo, C. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in sleep apnoea. Respirology (Carlton Vic). 8, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00494.x (2003).

Cao, M. T., Sternbach, J. M. & Guilleminault, C. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstuctive sleep apnea: benefits and alternatives. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 11, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2017.1305893 (2017).

Russell, T. Enhancing adherence to positive airway pressure therapy for sleep disordered breathing. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 35, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1390070 (2014).

Pase, M. P. et al. Sleep architecture, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive function in adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2325152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25152 (2023).

Vanek, J. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, depression and cognitive impairment. Sleep. Med. 72, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.03.017 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Therapeutic effects of CPAP on cognitive impairments associated with OSA. J. Neurol. 267, 2823–2828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09381-2 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. The genome sequence archive family: toward explosive data growth and diverse data types. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 19, 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.001 (2021).

Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center. China national center for bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D27–D38. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab951 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82400115), and the National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Projects of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L., Y.O., Z.S. and R.O. made the conceptualization. Y.O., T.L. and Z.S. helped investigation and provided resources. Q.L., Y.O., Y.H. and X.Q. conducted formal analysis. Q.L. and Y.O. finished writing. R.O. took charge of fuding acquisition and project administration. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the medical ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, approval number [Acceptance no. 2019 − 215]. This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled individuals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 1 where in the "OSA array data", GSE49800, GSE75097, and GSE133601 were incorrectly given as GSE49800, GSE75097, GSE135917 and GSE133601.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Ou, Y., Liu, T. et al. Preliminary evidence of immune infiltration and neutrophil degranulation in peripheral blood of non-obese OSA patients related to cognitive decline. Sci Rep 15, 3481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88034-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88034-z