Abstract

Air pollution is a critical global environmental issue, further exacerbated by rapid industrialization and urbanization. Accurate prediction of air pollutant concentrations is essential for effective pollution prevention and control measures. The complex nature of pollutant data is influenced by fluctuating meteorological conditions, diverse pollution sources, and propagation processes, underscores the crucial importance of the spatial and temporal feature extraction for accurately predicting air pollutant concentrations. To address the challenges of data redundancy and diminished long-term prediction accuracy observed in previous studies, this paper presents an innovative approach to predict air pollutant concentrations leveraging advanced data analysis and deep learning methods. The proposed approach, termed KSC-ConvLSTM, integrates the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm, spatio-temporal attention (STA) mechanism, the residual block, and convolutional long short-term memory (ConvLSTM) neural network. The KNN algorithm adaptively selects highly correlated neighboring domains, while the residual block, enhanced with the STA mechanism, extracts spatial features from the input data. ConvLSTM further processes the output from STA-ConvNet to capture high-dimensional temporal and spatial features. The effectiveness of the KSC-ConvLSTM approach was validated through predictions of PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing and its surrounding urban agglomeration. The experimental results indicate that the KSC-ConvLSTM approach outperforms benchmark approaches in single-step, multi-step, and trend prediction. It demonstrates superior fitting accuracy and predictive performance. Quantitatively, the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach reduces the root mean square error (RMSE) by 4.216–8.458 for prediction averages of 1–12 h of PM2.5 in Beijing, compared with the benchmark approach. The findings show that the KSC-ConvLSTM approach shows considerable potential for predicting, preventing, and controlling air pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global environmental challenge of air pollution has generated significant public concern1. According to the State of Global Air 2024, air pollution has emerged as the second-leading global risk factor for mortality. Premature deaths attributed to air pollution have increased significantly, from 4.9 million in 2017 to 6.67 million in 2019, and further to 8.1 million in 2021, with this number continuing to rise2,3,4. The risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory conditions, lung infections, and cancer rises significantly with the inhalation of polluted air5. Accurate air pollution forecasting acts as an early warning system for government agencies and the public, supporting informed decision-making during periods of severe pollution6. Therefore, accurately forecasting air pollutant levels is essential for effective environmental management and pollution control, carrying substantial social value7.

At present, research on air pollutant concentration prediction primarily relies on two prominent approaches: numerical simulation modeling and data-driven modeling8. Numerical simulation modeling leverages meteorological theories and statistical methods to simulate the exhaust, diffusion, and conversion processes of pollutants in the atmosphere, ultimately providing predictions of pollutant concentrations9. Data-driven modeling, on the other hand, focuses on learning and analyzing historical pollutant concentration data to achieve pollutant concentration prediction10.

Numerical modeling primarily relies on atmospheric dynamics, meteorological principles, and statistical methods to develop equations that represent the relationship between air pollutants and meteorological data, facilitating short-term predictions of pollutant concentrations11. These models tackle intricate differential equations to replicate the environmental dynamics and dispersion patterns of pollutants in the atmosphere12. Common numerical models include the Community Multiscale Air Quality model13, the Nested Air Quality Prediction Model System14, and the Weather Research and Forecast Chemistry Model15. Numerical models, while accounting for changes in chemistry and pollutant transport pathways, are limited by uncertainties related to meteorological conditions, the characterization of pollution sources, and the complexities of the transformation processes. Additionally, the inherent complexity and high computational demands of these models further limit their accuracy and feasibility16.

In contrast, data-driven modeling approaches offer greater simplicity, efficiency, and ease of implementation17. These methods analyze historical pollutant concentration data to uncover relationships between past data and pollutant concentrations during the prediction period, enabling the reasonable prediction of future pollutant concentrations based on historical data and current conditions18. Data-driven modeling could be further categorized into machine learning and deep learning approaches19. Machine learning models, a crucial facet of artificial intelligence, leverage trends in pollutant concentration and the interconnections between pollutants and meteorological conditions to generate pollutant concentration predictions20. Frequently utilized machine learning models include random forest models21, autoregressive sliding average models22, and support vector machine (SVM) models23. Machine learning models demonstrate superior robustness in handling nonlinear data relationships, lower computational complexity, faster computation speeds, and simpler implementation24. However, their reliance on manually constructed parameters and dependence on human expertise limit their adaptability. Furthermore, as the size of the dataset increases, machine learning models may struggle to reduce redundant data, which can hinder their learning efficiency and generalization capabilities25.

Recently, deep learning models have outperformed traditional machine learning models in spatio-temporal predictions, particularly in areas such as image recognition26, natural language processing27, and prediction tasks based on historical data28,29,30,31. These models excel at exploring complex, higher-order nonlinear relationships through deep networks, demonstrating strong self-learning capabilities and enhanced robustness. Notably, they are adept at learning spatially and temporally dependent deep features with greater accuracy. In air pollution prediction, deep learning models like recurrent neural networks (RNN) and their variants, such as long short-term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent unit (GRU)32, and aggregated long short-term memory network have demonstrated considerable promise33. These models take into account both current and past information, making them highly suitable for time series prediction of air pollution. Accurate predictions of pollutant concentrations depend on effectively simulating the spatio-temporal interactions between complex, non-stationary air pollutants and meteorological data34. However, a single RNN-based network struggles with managing extensive spatial and temporal data.

To address the limitations of an individual RNN-based network, researchers have integrated additional deep learning techniques to enhance the effectiveness of spatio-temporal modeling. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), with their shared weights and neighborhood identification capabilities, provide powerful feature extraction for models35. As a result, CNNs are widely used to extract spatial and temporal characteristics and forecast air pollution36. Sayeed et al. used air pollutant and meteorological data as inputs to predict ozone concentrations for the next 24 h using a CNN model37. The CNN model was found to surpass the GRU in performance according to the experiments. However, single network structures are still deficient in the deep extraction of large-scale spatial and temporal data. As a result, hybrid models that combine the strengths of RNNs and CNNs are increasingly being employed. Considering the spatio-temporal correlation, Ding et al. developed an integrated model combining CNN and LSTM to predict air pollution concentrations38. The CNN-LSTM model achieves better performance compared to the individual LSTM model. Pak et al. adopted the CNN-LSTM model to forecast air pollution concentration with effective error control39. Faraji et al. developed a 3D CNN-GRU combined model for predicting air pollution concentration on an hourly and daily basis40. The proposed approach demonstrated superior performance compared to other individual models. Similar outcomes were verified by Sharma et al. in their study41. Other algorithms have been combined with RNNs to enhance prediction results, including ED-BiLSTM42and VMD-GAT-BiLSTM43.

Furthermore, attention mechanisms have been employed to enhance the precision of prediction methods in fields such as natural language processing and image recognition, where they have achieved significant results44. The mechanism works by mimicking the human ability to selectively focus on a subset of available information while ignoring other irrelevant or less important data. Attention mechanisms have been widely applied in time-series prediction tasks across diverse domains, such as traffic forecasting45, power generation46, and flood prediction47. Recently, attention mechanisms have been applied in air pollution prediction to capture the spatio-temporal correlations in pollution data48. Li et al. extracted spatio-temporal correlation by embedding spatio-temporal attention and self-attention, which led to a substantial enhancement in prediction accuracy49. Similarly, Zhang et al. embedded spatio-temporal attention into residual CNN to forecast air pollutant concentrations over multiple and various periods in the Yangtze River Delta region50.

As deep learning architectures grow in complexity, tackling challenges like gradient vanishing and network degradation has become a critical aspect of model design. Commonly employed techniques to address these challenges include batch normalization, residual networks, advanced weight initialization methods, and specialized optimization algorithms. For instance, Rajdeep et al. enhanced model learning performance by incorporating a normalization layer to standardize features51. Xie et al. employed ResNet to address network degradation and gradient vanishing issues by leveraging residual connections, thereby enabling smoother gradient flow in deeper networks52. Tian further improved the convergence rate of neural networks by refining the traditional Adam optimization algorithm, thus enhancing training efficiency and reducing the impact of gradient vanishing53.

Despite notable advancements in pollutant concentration forecasting, several challenges persist within the existing studies: (1) Disruption of Data Regularity: The separate extraction of spatial and temporal features can disrupt the inherent regularity of the data, which refers to the intrinsic relationships or patterns present within its variation range. (2) Impact of Redundant Data: While leveraging big data is crucial for enhancing approach performance, the influence of redundant or weakly correlated data has not been fully explored, potentially affecting approach efficiency and accuracy. (3) Weak Long-Term Forecasting: Many approaches demonstrate diminished long-term forecasting capabilities, with predictive performance deteriorating rapidly as the forecasting horizon extends. (4) Limited Approach to Network Challenges: Solutions to gradient vanishing and network degradation often focus on isolated techniques, such as batch normalization or residual connections, rather than a holistic integration of strategies within the approach architecture to address these issues comprehensively.

To address the identified challenges and improve the reliability of air pollution forecasts, we introduce a deep learning hybrid approach, KSC-ConvLSTM, which integrates the k-nearest neighbors (KNN), spatio-temporal attention (STA), residual block, and convolutional long short-term memory (ConvLSTM). The key contributions and innovations of this work are as follows:

(1) Preserving Data Regularity through Integrated Spatio-Temporal Feature Extraction: We emphasize the interdependence between temporal and spatial features, thus preserving the inherent data regularity and the intrinsic relationships or patterns observed within the scope of data variation. ConvLSTM networks perform spatio-temporal feature extraction on time-series data enriched with high-dimensional spatial features from residual blocks. This approach prevents the disruption of data patterns that often results from separate spatial and temporal feature extraction.

(2) Optimizing Data Relevance to Enhance Prediction Accuracy: In the approach’s base layer, we utilized the KNN algorithm to select data from highly correlated neighborhoods, filtering out irrelevant or weakly correlated data. This selective input strategy reduces redundant data, accelerates model training, and improves predictive accuracy and efficiency.

(3) Comprehensive Solution to Gradient Vanishing and Network Degradation: We developed a holistic approach architecture to address gradient vanishing and network degradation. Although KNN does not directly resolve these issues, its integration within the approach framework contributes to gradient stability. Embedding the STA module within residual block enhances the extraction of spatio-temporal features without excessive network depth, while ConvLSTM, leveraging convolutional layers and memory units, mitigates gradient vanishing and feature degradation.

These innovations collectively enhance the approach’s effectiveness in accurately predicting air pollutant concentrations, offering a robust solution for improved environmental management and public health protection.

Data description and analysis

Study area

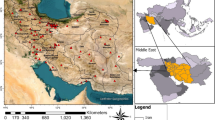

This paper focuses on Beijing and its surrounding urban agglomerations, as depicted in Fig. 1. This region, marked by a dense population, high levels of social activity, and its status as China’s political and economic center, serves as a compelling subject for research. This region experiences a typical continental monsoon climate, with hot summers and cold winters, accompanied by pronounced seasonal variations. Geographically, it is semi-enclosed, surrounded by mountains to the north and west, which impede pollutant dispersion. As one of China’s most densely populated and industrialized areas, it faces high energy consumption and intense emissions, exacerbating air quality issues.

Despite notable progress in air pollution prevention and control in recent years, China’s environmental situation still requires improvement to meet international standards. Research indicates that PM2.5is a primary contributor to air pollution, accounting for approximately 38.9% of polluted days annually each year54. As a result, accurate forecasting of PM2.5 concentrations in this region is crucial for effective air quality management and policy formulation.

Data preprocessing

PM2.5 exhibits interrelationships with other pollutants, like PM10 and O3. As an example, PM2.5 and O3 have similar precursors, including NOx, and participate in various atmospheric processes55. This paper utilizes six pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, O3, NO2, CO, and SO2) along with the air quality index (AQI) as inputs to the approach for predicting PM2.5 concentration. To streamline the input structure, mean values of these variables from multiple monitoring stations within each city were used. Additionally, meteorological factors such as temperature, wind speed, and humidity are critical in influencing the dispersion of air pollutants.

Hourly concentration data and AQI for the six major pollutants in the study area were collected from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/) for the duration from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021. Moreover, hourly meteorological data for this same period were collected from Open Weather Map (https://openweathermap.org/). Altogether 17,544 data points were collected for each variable.

The collected data require preprocessing due to missing values ranging from 162 to 1782 data points, with a missing rate of 0.92–10.15%. These missing values need to be handled appropriately to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the predictive approach. First, linear interpolation was utilized to address any gaps in the data. This method estimates missing values based on the linear relationship between adjacent known data points, effectively preserving the overall trend and patterns of the data. Although linear interpolation can sometimes introduce complex nonlinear variations that may impact the approach’s prediction accuracy, its simplicity, efficiency, and ability to ensure smooth transitions make it a suitable approach for this study, particularly given the low missing data rate and clear temporal dependencies in the dataset. Second, to mitigate the significant differences in data across various influencing factors, the data were normalized using the Min-Max function36. The data normalization formula is as Eq. (1).

Where ynorm represents the normalized data value, y is the original data value, ymin and ymax refer to the minimum and maximum values of the data, respectively. The dataset was split into three portions: 70% allocated for training, 20% for validation, and 10% designated for testing. Table 1 presents the statistical summaries for Beijing and Tianjin cities to provide a clearer representation of the data.

Data distribution characteristics

Temporal dimension exploration

Using data from Beijing in 2021, we analyzed the distribution characteristics of air pollutant concentrations the correlation with meteorological data. Figure 2 illustrates the variations in air quality, including the AQI and the concentration levels of various pollutants. The trends in pollutant concentrations show a consistent pattern, indicating a strong implicit relationship between these pollutants, such as PM2.5, PM10, and CO, all of which show a significant increase around 2000 h.

Analysis indicates that PM2.5 concentrations in 2021 occasionally exceeded the threshold of 35 µg·m−3, leading to minor adverse effects on sensitive groups. Notably, PM2.5 concentrations exceeded the 75 µg·m−3limit for 13.01% of the time during the year, directly impacting human health and daily activities56. Therefore, accurate predictions for PM2.5 concentrations must account for both the implicit relationships between PM2.5 and other factors, as well as the potential health implications of elevated PM2.5 levels.

Figure 3 illustrates the annual variation of relevant meteorological data. Air temperature, dew point temperature, maximum air temperature, minimum air temperature, and sensible temperature exhibit a pattern of initial increase followed by a decrease, whereas atmospheric pressure demonstrates an inverse trend. The similar variation patterns of these meteorological elements suggest potential interrelationships. For instance, high temperatures are often associated with low atmospheric pressure, and vice versa. These observed trends in both pollutant and meteorological data imply an implicit association, where changes in meteorological conditions could influence the dispersion and concentration of pollutants like PM2.5.

To address the dependence of pollutant concentrations on meteorological factors, both pollutant and meteorological data were incorporated as approach inputs. This approach enables the extraction of implicit features that are related to both pollutants and meteorological data, thereby improving the accuracy and precision of PM2.5concentration prediction. This implicit feature results from the interaction between pollutants and meteorological factors. Numerous studies have demonstrated that incorporating meteorological data significantly enhances the accuracy of air pollution prediction57.

Spatial dimension exploration

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the annual variations in air pollutant concentrations and meteorological information, which are explored in further detail in this study. As a prominent city in the study area, Beijing provides valuable insights into the spatial characteristics of PM2.5 concentrations. This paper examines PM2.5 concentration data from Beijing for 2021. Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients of pollutant concentrations among Beijing and its neighboring cities, while Fig. 4 depicts the annual variation of PM2.5 concentration values.

As shown in Table 2; Fig. 4, cities located closer to Beijing exhibit higher correlation coefficients with the capital’s air pollutant concentrations. In contrast, as the distance between other cities and Beijing increases, the correlation coefficients tend to decrease gradually. The PM2.5 concentration distribution curve for Langfang City closely mirrors that of Beijing, indicating a strong correlation in their air quality patterns. In contrast, the curves for Datong City and Zhangjiakou City, which are farther from Beijing, show less similarity to Beijing’s data distribution. This distance-dependent effect highlights the spatial relevance of air pollutants. Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate that the overall trend of PM2.5across various cities exhibits significant consistency across both spatial and temporal dimensions. The observed correlation between pollutant concentrations in Beijing and its surrounding cities underscores the necessity of considering spatial correlations when predicting pollutant concentrations. Incorporating spatial attributes is crucial, and potential spatio-temporal attention mechanisms should be considered to enhance air pollution prediction performance58.

Methodology

The framework of the proposed prediction approach

This paper presents the KSC-ConvLSTM approach for predicting air pollutant concentrations, detailing the process from the initial data input to the final results. Figure 5 shows the framework of the proposed pollutant concentration prediction approach. The KSC-ConvLSTM approach processes the historical data of pollutants and meteorological conditions for the previous n hours, denoted by \(x=\{ {x_t},{x_{t+1}}, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,x{}_{{t+n - 1}},{x_{t+n}}\} ,{x_{t+n}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{s \times i}}\). Here, S represents the number of observation stations and i represents the aggregate amount of pollutant and meteorological information, x represents the historical data from time t to t + n. The approach outputs the pollutant concentration for the next r hours, denoted as \(\hat {y}=\{ {\hat {y}_t},{\hat {y}_{t+1}}, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,{\hat {y}_{t+r - 1}},{\hat {y}_{t+r}}\} ,{\hat {y}_{t+r}} \in R\), where \({\hat {y}_{t+r}}\) represents the approach’s predicted value at a given point in time.

Unlike traditional pollutant concentration prediction methods, this paper introduces a novel three-layer KSC-ConvLSTM approach. The base model, KNN-STA-ConvNet, utilizes the KNN algorithm to adaptively select highly correlated neighboring domains. Additionally, it incorporates a spatio-temporal attention module into the residual block to emphasize the spatio-temporal characteristics of both pollutant and meteorological data. The residual networks employ a convolution kernel of consistent size in each layer to perform convolution operations on the input data. This process is designed to extract deep spatial features from input data \(out=\{ ou{t_t},ou{t_{t+1}}, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,ou{t_{t+n - 1}},ou{t_{t+n}}\}\). The ConvLSTM layer serves as the second layer, responsible for extracting both spatial and temporal features of pollutant concentrations. By adding a convolution operation to the gating mechanism of the LSTM, the ConvLSTM is able to capture both spatial features and the temporal dependencies traditionally modeled by LSTM. This enhancement enables the approach to better handle spatio-temporal data, making it more effective for predicting air pollutant concentrations. Similar to LSTM, ConvLSTM utilizes its gating mechanism to capture time-series features of the data while employing convolution operations to extract spatial features. By combining these spatio-temporal features, ConvLSTM captures the intrinsic characteristics of the data, thereby preventing the disruption of inherent correlations that can arise from separate characteristic extraction. The final layer, a fully connected layer, processes the output from the ConvLSTM to predict the air pollutant concentrations.

K-nearest neighbors

Spatial correlation studies indicate that the spatial correlation between a site and its neighboring sites can vary. Due to its simplicity, flexibility, and effectiveness in capturing spatial correlations, KNN is employed in the proposed approach to adaptively select highly correlated neighboring cities as shared inputs. To select the optimal correlated cities as inputs for the approach, we set a correlation threshold and search from distant to proximate locations for neighboring cities with correlation values exceeding this threshold. An adaptive method is used to select neighboring cities, with ki representing the number of neighboring cities for each city, which varies from city to city. Assuming that the lower quartile of all ki values is kQ1, meaning that 75% of ki values are greater than kQ1. To ensure consistency in data dimensions, each city uses data from an identical number of neighboring cities. When ki < kQ1, kQ1 - ki is added as a supplement; when ki ≥ kQ1, kQ1 is used as the number of neighboring cities, representing those most correlated with the current city.

In this paper, the KNN algorithm employs the Haversine distance metric, as it effectively accounts for the Earth’s curvature, making it suitable for calculating distances between points based on latitude and longitude coordinates. The Haversine formula is presented in Eq. (2):

Where d denotes the distance between two points; r represents the Earth’s radius, often approximated as 6371 km, \({\varphi _1}\) and \({\varphi _2}\) refer to the latitudes of two points; \(\Delta \varphi\) is the difference in latitude; \(\Delta \lambda\) is the difference in longitude.

Spatio-temporal attention

The concept of attention is inspired by human visual perception, where individuals focus their limited attention on salient information while ignoring irrelevant details. The core of the attention mechanism lies in identifying internal correlations within raw data, filtering out irrelevant information, and assigning higher weights to the more significant data points59. Spatio-temporal attention effectively extracts and strengthens spatio-temporal dependencies, improving the approach’s predictive ability and robustness, particularly for complex spatio-temporal problems like pollutant concentration forecasting. Figure 6 illustrates the framework of the spatio-temporal attention module. Where C denotes the window size (size of historical data input), H denotes city information, and W denotes air pollutant characteristics and meteorological information.

This paper leverages the strong weight distribution capabilities of spatio-temporal attention to capture the spatio-temporal characteristics of pollutant concentration and meteorological data. By combining spatial and temporal attention, the approach effectively highlights the key features relevant to air pollution prediction60. Given the feature inputs selected by KNN, the activation function receives the element-wise multiplication of the temporal and spatial attention distributions to generate the spatio-temporal attention distribution. Finally, the resulting spatio-temporal attention distribution is element-wise multiplied with the feature inputs to obtain the final refined input \(F^{\prime\prime}\). It can be obtained through Eq. (3):

Spatial attention

The spatial attention module is designed to better capture the spatial information of features selected by KNN and assign them different weights. Figure 7 (a) depicts the structure of the spatial attention module. First, MaxPooling and AveragePooling operations are applied to the feature inputs to capture different aspects of the spatial information. The results from these operations are then concatenated, creating a valid feature map that represents the spatial characteristics of the input data. Afterward, a convolution operation is applied to reduce the feature map to a single channel, simplifying the information. Finally, the feature map is processed through a sigmoid activation function to produce the spatial attention weight distribution. The formulation of the spatial attention mechanism is presented in Eq. (4):

where Maxpool(·) indicates maximum pooling, Avgpool(·) indicates average pooling, and Conv(·) indicates convolutional layers.

Temporal attention

Unlike spatial attention, the temporal attention mechanism concentrates on how historical information affects the current and future states. The architecture of the temporal attention module is presented in Fig. 7 (b). As the channel dimensions of the original inputs represent time-lagged information, the temporal attention module adaptively identifies internal correlations among these inputs. The temporal attention module strengthens significant historical information and suppresses irrelevant details by analyzing the weights of each channel.

The temporal attention mechanism initiates by applying MaxPooling and AveragePooling operations to aggregate spatial feature data, generating two distinct feature vectors that highlight key spatial characteristics. These vectors are then passed through a shared multilayer perceptron (MLP) and combined via element-wise summation. Finally, a sigmoid activation function is applied to produce the temporal attention weight distribution, enabling the approach to emphasize relevant temporal features. The formulation of the temporal attention module is presented in Eq. (5):

Where MLP(·) denotes a multilayer perceptual machine.

STA-ConvNet

Embedding STA into the residual block not only avoids the computational burden caused by excessively deep networks but also effectively alleviates the vanishing gradient problem through the residual block. In addition, the residual block’s intrinsic strengths can also be utilized to capture spatial relationships between air pollutants and meteorological factors across various cities within an inter-regional setting. The residual block receives the time-series formatted data selected by the KNN module. The input to the residual block is a single-channel feature map with an input size of 24 × 10 × 1. After that, convolution operations are performed on the data to extract spatial features, which utilize identical convolution kernels ([3 × 3], [3 × 3]). Concurrently, the spatio-temporal attention module extracts temporal and spatial weights. The combination of two modules in each residual cell is shown in Fig. 8.

ConvLSTM

By integrating convolutional operations with long short-term memory networks, ConvLSTM effectively approaches dynamic changes in spatio-temporal sequence data. This enhances the approach’s ability to predict complex spatio-temporal patterns, particularly in capturing long-term dependencies and intricate temporal variations. This paper employs ConvLSTM to extract spatio-temporal features and forecast pollutant concentration from time-series data. ConvLSTM receives high-dimensional spatial features output from STA-ConvNet. By integrating the gating mechanism with convolution operations, ConvLSTM efficiently addresses spatio-temporal feature extraction in high-dimensional time-series data. During the pollutant concentration prediction phase, ConvLSTM utilizes the extracted spatio-temporal correlation features to generate predicted pollutant values. The fully connected layer gets the state of each moment from the ConvLSTM output to make the prediction.

Figure 9 (a) illustrates the integrated spatio-temporal feature extraction process utilizing ConvLSTM, with (ht, ct) representing the cell state. Each ConvLSTM cell comprises three gates: it represents the input gate, ft denotes the forget gate, and ot represents the output gate. These gates function similarly to those in LSTM. Unlike LSTM, ConvLSTM employs a convolution function for input-to-state and state-to-state transformations rather than a fully connected operator, enabling the capture of richer spatio-temporal features when processing spatio-temporal data.

The extraction of spatio-temporal features by ConvLSTM is shown in Fig. 9 (b), which could be expressed through the following equation:

Where Conv(W, x) represents the convolution function, \(\circ\) denotes the Hadamard product, tanh(·) denotes the Tanh function, and \(\sigma ( \cdot )\) stands for the sigmoid function. The previous output and state of the ConvLSTM unit are represented by ht−1 and ct−1, respectively. The current cell’s input is symbolized by xt, while gt stands for the potential memory cell involved in transferring information. The convolution kernel is denoted by W, and b refers to the bias term.

esults

Among the six categories of air pollutants, PM2.5is particularly concerning due to its finer particle size, which enables it to stay airborne for prolonged durations. This characteristic increases its likelihood of engaging in chemical reactions with other pollutants, thereby posing significant health hazards61. Statistical studies indicated that air pollution led to 6.67 million premature deaths globally in 2019, with 1.8 million of these attributed to PM2.5emissions, accounting for over 26% of all early fatalities62. In China, PM2.5 pollution led to 711,000 deaths in urban areas, accounting for 39.5% of global PM2.5-related urban fatalities, with an associated economic loss of 2.75 trillion RMB63. Controlling PM2.5 effectively is crucial not only for safeguarding public health but also for minimizing financial losses. Consequently, this paper demonstrates the feasibility and reliability of the developed approach by applying it to predict PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing.

Evaluation metrics

The approach proposed in this paper uses Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function. By minimizing MSE, the approach aims to reduce the difference between the predicted and true values, with larger errors being penalized more heavily than smaller ones. This characteristic makes MSE particularly effective for tasks that require strict penalties for large deviations from the true values. During the training process, the Adam optimization algorithm is employed to minimize MSE and iteratively adjust the approach parameters.

The proposed approach in this paper is evaluated against other deep learning approaches using the same dataset. The efficacy of the suggested method is proven by several evaluation metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Coefficient of Determination (R²), and Index of Agreement (IA). Lower RMSE and MAE values indicate a more precise fit between the prediction approach and the target data. The values of R² and IA range from 0 to 1, with values nearing 1 signifying a superior approach fit. The formulas for each indicator are as follows:

where n represents the sample size of the approach input set, \(\hat y_i\) signifies the approach’s predicted value, yi stands for the actual pollutant concentration, and \(\bar y\) denotes the average pollutant concentration.

Experimental design and parameter setting

All experiments were conducted on a computer with a Windows 10 operating system (CPU: AMD Ryzen 5 3550 H with Radeon Vega Mobile Gfx @ 2.10 GHz, GPU: NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650, RAM: 8 GB). Data processing, approach construction, and training were carried out using several open-source libraries and frameworks, including Numpy, Pandas, and TensorFlow, with Anaconda (Python 3.9.7) as the programming software.

To optimize the model’s hyperparameters, this study employed random search experiments by adjusting parameters such as Dropout, Batch Size, Learning Rate, and Epochs, followed by multiple rounds of training. The results of the experiments are shown in Table 3. The experimental results indicate that the optimal combination of hyperparameters—Dropout = 0.5, Batch Size = 128, Learning Rate = 0.0001, and Epochs = 50—achieved the best validation accuracy of 92.3%, with a training time of 2.1 h. The various parameters used in the method are listed in Table 4.

Single-step prediction

The approach employs hourly PM2.5 concentration values from Beijing as the predictor variable. In the scenario of single-step prediction, the historical time series used as input spans 6 h to predict the PM2.5 concentration for the subsequent hour.

Impact of the number of relevant cities on PM2.5 concentration prediction

Table 5 presents the impact of selecting the number of relevant cities on the approach’s performance. The findings indicated that including data inputs from different numbers of neighboring cities significantly affects the prediction accuracy.

Notably, the gradual increase in the number of selected cities indicates an expanding scope outward from Beijing, as detailed in Sect. 2.3.2. Experimental results in Table 5 show that using data from the two most relevant cities yields the best performance for PM2.5 concentration prediction. This conclusion provides valuable insights for subsequent studies.

Comparison with other approaches

Table 6 shows the results of single-step PM2.5concentration predictions. The approaches include SVM, SVR, BP, CNN, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM, Air-PredNet64, STARes-CNN and KSC-ConvLSTM. Their performance is estimated by making use of RMSE, MAE, R², and IA metrics. The prediction of PM2.5 concentrations by the KSC-ConvLSTM approach is more precise than other deep learning approaches. Specifically, KSC-ConvLSTM achieves reductions in RMSE and MAE to 7.347 µg·m−3 and 4.674 µg·m−3, respectively, while improving R2 and IA to 0.959 and 0.989, indicating a significant enhancement in prediction accuracy.

When comparing single-structure approaches, such as CNN and LSTM, with hybrid approaches like CNN-LSTM and ConvLSTM, it is evident that the hybrid approaches significantly outperform the single-structure approaches. This is because CNN-LSTM and ConvLSTM leverage deeper spatio-temporal features, enabling them to capture more complex patterns, thus outperforming the CNN and LSTM approaches. Air-PredNet and STARes-CNN improve upon the network structure by deepening the architecture and incorporating STA to learn more intricate features, while using residual block to mitigate issues such as network degradation and vanishing gradients. These enhancements allow Air-PredNet and STARes-CNN to outperform traditional approaches like CNN-LSTM. However, KSC-ConvLSTM surpasses even these hybrid approaches. For example, when compared using the RMSE metric, the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach improves by 6.527 µg·m−3, 4.990 µg·m−3, 3.780 µg·m−3, and 2.857 µg·m−3 over CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM, Air-PredNet, and STARes-CNN, respectively. The performance improvement is attributed to KSC-ConvLSTM’s integration of multiple methods, which enhances its ability to capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies and account for the influence of neighboring regions.

In practical applications with limited computational resources, computational efficiency is as important as predictive accuracy65. This paper compares the runtime of the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach with that of LSTM, CNN-LSTM, STA-ResCNN, and STARes-LSTM, as shown in Table 7.

As approach complexity increases—such as through the addition of convolutional layers, residual networks, and spatio-temporal attention mechanisms—the time per training step also increases. This is due to the deeper network structure and more complex computations, resulting in longer training times. However, the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM effectively reduces runtime while maintaining prediction accuracy. The KNN algorithm’s data pruning plays a crucial role in alleviating the burden on subsequent processing. While experimental conditions were kept consistent and results were averaged over multiple runs, variations in time periods may still introduce some bias in the experiments.

Figure 10 displays the fitting ability and prediction results of several approaches in single-step prediction. The horizontal axis of Fig. 10 (a) covers 1000 h in a row chosen randomly from the test set for assessing the approach’s prediction precision. The predicted values are shown as red lines, whereas the actual values are represented as blue lines. This visualizes the fitting trends and predictive effects of the four approaches on a randomly selected test set. Figure 10 (b) shows the PM2.5 concentration prediction values for 1000 randomly chosen hours from the test set. The actual PM2.5 values are shown along the horizontal axis, and the predicted values are plotted along the vertical axis. The y = x function is depicted by the black line, while the black dots represent the interpolation between the actual and predicted values. Comparing the dispersion, it is evident that the KSC-ConvLSTM approach exhibits the least amount of dispersion.

Compared with ConvLSTM, Air-PredNet, and STARes-CNN, the KSC-ConvLSTM approach exhibits a better fitting trend and the least dispersion. The KSC-ConvLSTM approach also performs more accurately in predicting abrupt changes in PM2.5 concentration. Additionally, the correlation analysis revealed that the correlation coefficients of LSTM, CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM, and KSC-ConvLSTM were 0.979, 0.981, 0.983 and 0.985, respectively. This indicates that the predicted values from the KSC-ConvLSTM approach showed the strongest correlation with the actual values.

Multi-step prediction

Predicting pollutant concentrations with a single-step approach is insufficient for real-world applications. Therefore, predicting pollutant concentrations over a future period, i.e., multi-step prediction, is essential. This capability is particularly beneficial for residents planning travel, as it provides a more comprehensive understanding of potential air quality trends over time.

Approach performance on PM2.5 concentration prediction

This paper explores forecasting PM2.5 concentrations over a time span of 1–12 h, segmented into six multi-step prediction tasks using the KSC-ConvLSTM approach. Table 8 presents the outcomes for these tasks, employing a consistent KSC-ConvLSTM approach structure throughout the experiments.

As shown in Table 8, both the historical input time series length and prediction intervals increase concurrently. Notably, the predictive performance of the KSC-ConvLSTM approach generally diminishes as the prediction horizon extends. For the simultaneous 1–2 h prediction task, extending the historical input time series from 4 to 6 h led to an increase in prediction error, but the RMSE and MAE only increased by 0.513 µg·m−3 and 0.473 µg·m−3, respectively. This implies that in a simultaneous multi-step prediction task, simply increasing the historical input length does not guarantee improved prediction accuracy or reduced error. The effectiveness of longer input lengths is also influenced by factors such as the approach structure, parameter settings, and the data source, among other conditions. Through iterative refinement, optimal historical input lengths were determined for each prediction task.

Ablation experiments for each component of the proposed approach

This paper evaluates the contribution of each component in the KSC-ConvLSTM approach through ablation experiments, as shown in Table 9. The approach integrates KNN, rualesidual block, ConvLSTM, and a spatio-temporal attention module.

First, the impact of the KNN module was assessed by comparing the performance of STARes-ConvLSTM with KSC-ConvLSTM, where KSC-ConvLSTM outperformed STARes-ConvLSTM, highlighting the value of the KNN module. Next, we evaluated the effect of the temporal attention module by comparing STA-ConvNet, ResNet, Res-ConvLSTM, and STARes-ConvLSTM. Results showed that both STA-ConvNet and STARes-ConvLSTM yielded better prediction accuracy compared to ResNet and Res-ConvLSTM, affirming the enhancement provided by the temporal attention module. Overall, the ablation experiments confirm that each component in the KSC-ConvLSTM approach contributes significantly to its superior predictive performance.

Comparison with other methods

As presented in Table 10, we assessed the performance of the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach and compared it with other advanced deep learning approachs for multi-step prediction, using RMSE and MSE metrics. The comparison approachs included baseline approachs and several advanced deep learning architectures, such as ConvLSTM, STAResCNN, and STARes-SaLSTM. ConvLSTM effectively captures spatiotemporal dependencies but is prone to overfitting and requires substantial computational resources. STAResCNN integrates spatiotemporal attention mechanisms to focus on the dependencies across both dimensions and employs ResNet to mitigate approach degradation. However, its performance may be constrained when handling data with strong temporal dependencies. STARes-SaLSTM processes both spatial and temporal features, with the self-attention mechanism enhancing the approach’s ability to capture long-range dependencies. Nonetheless, its complex structure leads to longer training times and higher computational demands. In contrast, the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach excels in extracting spatiotemporal features through a combination of multiple methods and addresses the impact of redundant data through data pruning. While it offers substantial predictive accuracy, it is less suitable for real-time applications due to its computational complexity.

As the prediction duration increases, the predictive performance of all approachs consistently declines. This trend is due to the increased complexity and uncertainty associated with longer prediction horizons, making accurate forecasting more challenging. However, compared with the other approachs, the proposed approach exhibits the slowest rate of performance degradation in multi-step prediction, achieving the lowest prediction error.

Trend prediction

To showcase the fitting precision of the KSC-ConvLSTM approach, pollutant concentration and meteorological data from the past 24 h are used as inputs to predict pollutant concentrations for the next 48 h. These predictions are then compared with those generated by other baseline approachs. Tables 11 and 12 present the discrepancies in RMSE, MAE, R2, and IA for CNN, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM, STARes-SaLSTM, and the proposed KSC-ConvLSTM approach.

As the prediction time step increases, the KSC-ConvLSTM approach consistently outperforms other prediction approachs. It exhibits less variability compared to the alternative approachs, indicating its suitability for precise multi-step prediction of PM2.5 concentration.

The experimental findings consistently highlight KSC-ConvLSTM as the superior performer among all approachs tested, excelling in single-step, multi-step, and trend prediction of PM2.5 concentrations. This hybrid deep learning approach integrates a spatio-temporal attention mechanism with neighborhood extraction, proving highly effective in processing complex spatio-temporal data compared to other deep learning approachs.

Temporal analyses reveal significant periodic changes in pollutant concentrations and meteorological data, emphasizing their time-dependent nature. Spatially, PM2.5 concentrations across the studied cities exhibit coherent frequency correlations based on distance, underscoring spatial dependencies among pollutant concentrations. Comparative experiments underscore KSC-ConvLSTM’s ability to accurately forecast PM2.5 concentrations and their temporal dynamics across various time intervals.

In conclusion, the KSC-ConvLSTM deep learning hybrid approach, leveraging neighborhood extraction and spatio-temporal attention, provides valuable insights for enhancing air pollution management strategies.

Conclusion

This paper presents a convolution-sequence hybrid model-based approach to enhance the accuracy of air pollution concentration predictions. The proposed KSC-ConvLSTM model effectively identifies spatial and temporal characteristics, accurately reflecting fluctuations in pollutant concentrations. The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) Spatio-temporal feature extraction

Unlike conventional approaches that extract spatial and temporal features separately, the KSC-ConvLSTM approach processes high-dimensional spatial features directly from the residual blocks using ConvLSTM layers. This approach ensures the integrity and coherence of the data, allowing for more effective spatio-temporal feature extraction and improved prediction performance.

(2) Adaptive input selection

The integration of KNN helps the approach adaptively select only highly correlated neighboring data as input, reducing the impact of irrelevant or redundant information. This selective input strategy improves the approach’s efficiency and significantly reduces training time, enabling faster convergence and enhanced predictive accuracy.

(3) Enhanced spatio-temporal capabilities

The integration of the STA module within residual block further strengthens the approach’s spatio-temporal feature extraction capabilities. At the same time, residual block mitigates common network degradation issues encountered in deep learning approaches. Additionally, the combination of convolutional layers and memory units in ConvLSTM addresses the problem of gradient vanishing, alleviating prevalent challenges such as network degradation and gradient vanishing in deep learning.

Although the KSC-ConvLSTM approach demonstrates outstanding performance in PM2.5 concentration prediction, its generalizability to different geographic locations or other pollutants, as well as its real-time prediction capabilities, remain limited. The approach design and optimization were primarily based on PM2.5 data from Beijing and its surrounding areas, and may not be applicable to regions with different air pollution causes and characteristics or for predicting the concentrations of other pollutants. Therefore, further validation and adjustment are required to assess the approach’s effectiveness for widespread application. Additionally, since KSC-ConvLSTM integrates multiple deep learning components, its scalability and responsiveness may be constrained in large-scale deployment scenarios, particularly in real-time air quality prediction.

To enhance the approach’s applicability and prediction accuracy, future work will focus on the following aspects: first, extending the approach to predict other pollutants, with adjustments to account for the specific characteristics of each pollutant; second, integrating external data sources, such as satellite imagery, to improve the approach’s understanding of environmental factors. By incorporating additional data dimensions, the approach is expected to capture more complex spatiotemporal dependencies, thereby improving its predictive accuracy and generalizability.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Fong, I. H., Li, T., Fong, S., Wong, R. K. & Tallón-Ballesteros, A. J. Predicting concentration levels of air pollutants by transfer learning and recurrent neural network. Knowl. Based Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2020.105622 (2020).

HEI. State of Global Air 2024 (Health Effects Institute, 2024).

HEI. State of Global Air 2020 (Health Effects Institute, 2020).

HEI. State of Global Air 2019 (Health Effects Institute, 2019).

Li, L. et al. Ensemble-based deep learning for estimating PM2. 5 over California with multisource big data including wildfire smoke. Environ. Int.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106143 (2020).

Yang, H., Zhu, Z., Li, C. & Li, R. A novel combined forecasting system for air pollutants concentration based on fuzzy theory and optimization of aggregation weight. Appl. Soft Comput. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105972 (2020).

Maleki, H. et al. Air pollution prediction by using an artificial neural network model. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 21, 1341–1352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01709-w (2019).

Li, D., Liu, J. & Zhao, Y. Prediction of Multi-site PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing using CNN-Bi LSTM with CBAM. Atmosphere. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13101719 (2022).

Wu, X., Zhang, C., Zhu, J. & Zhang, X. Research on PM2.5 concentration prediction based on the CE-AGA-LSTM model. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147009 (2022).

Du, S., Li, T., Yang, Y. & Horng, S. J. Deep Air Quality forecasting using Hybrid Deep Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 33, 2412–2424. https://doi.org/10.1109/tkde.2019.2954510 (2021).

Li, D., Liu, J. & Zhao, Y. Forecasting of PM2.5 concentration in Beijing using Hybrid Deep Learning Framework based on attention mechanism. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111155 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. A novel encoder-decoder model based on read-first LSTM for air pollutant prediction. Sci. Total Environ.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144507 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. New method for evaluating winter air quality: PM2.5 assessment using community Multi-scale Air Quality modeling (CMAQ) in Xi’an. Atmos. Environ. 211, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.04.019 (2019).

Ge, B. et al. Wet deposition of acidifying substances in different regions of China and the rest of East Asia: modeling with updated NAQPMS. Environ. Pollut. 187, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.12.014 (2014).

Grell, G. A. et al. Fully coupled online chemistry within the WRF model. Atmos. Environ. 39, 6957–6975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.04.027 (2005).

Zou, G., Zhang, B., Yong, R., Qin, D. & Zhao, Q. FDN-learning: urban PM2.5-concentration spatial correlation prediction model based on Fusion deep neural network. Big Data Res.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdr.2021.100269 (2021).

Zhang, B., Zhang, H., Zhao, G. & Lian, J. Constructing a PM2.5 concentration prediction model by combining auto-encoder with Bi-LSTM neural networks. Environ. Model. Softw.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.104600 (2020).

Qin, D. et al. A novel combined prediction scheme based on CNN and LSTM for urban PM 2.5 concentration. Ieee Access. 7, 20050–20059. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2897028 (2019).

Huang, C. J., Kuo, P. H. A. & Deep CNN-LSTM Model for Particulate Matter (PM2.5) forecasting in Smart cities. Sensors. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072220 (2018).

Moursi, A. S. A., El-Fishawy, N., Djahel, S. & Shouman, M. A. Enhancing PM2.5 prediction using NARX-Based combined CNN and LSTM Hybrid Model. Sensors. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22124418 (2022).

Kumar, D. Evolving Differential evolution method with random forest for prediction of Air Pollution. Procedia Comput. Sci. 132, 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.05.094 (2018).

Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Wang, P., Qin, Y. & Wang, H. Forecasting of particulate matter time series using wavelet analysis and wavelet-ARMA/ARIMA model in Taiyuan, China. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 67, 776–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2017.1292968 (2017).

Leong, W. C., Kelani, R. O. & Ahmad, Z. Prediction of air pollution index (API) using support vector machine (SVM). J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103208 (2020).

Tu, X. Y. et al. Longer Time Span Air Pollution Prediction: the attention and Autoencoder Hybrid Learning Model. Math. Probl. Eng.. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5515103 (2021).

Kow, P. Y., Chang, L. C., Lin, C. Y., Chou, C. C. K. & Chang, F. J. Deep neural networks for spatiotemporal PM2.5 forecasts based on atmospheric chemical transport model output and monitoring data. Environ. Pollut.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119348 (2022).

Gu, K., Qiao, J. & Li, X. Highly efficient picture-based prediction of PM2.5 concentration. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron.. https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2018.2840515 (2019).

Yi, J., Ni, H., Wen, Z., Liu, B. & Tao, J. CTC regularized model adaptation for improving LSTM RNN based multi-accent Mandarin speech recognition. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/iscslp.2016.7918420

Chen, Y., An, J., Yanhan, Farouk, A. & Zhen, D. A novel prediction model of PM2.5 mass concentration based on back propagation neural network algorithm. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 37, 3175–3183. https://doi.org/10.3233/jifs-179119 (2019).

Kim, J., Wang, X., Kang, C., Yu, J. & Li, P. Forecasting air pollutant concentration using a novel spatiotemporal deep learning model based on clustering, feature selection and empirical wavelet transform. Sci. Total Environ. . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149654 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. PM2.5 concentrations forecasting in Beijing through deep learning with different inputs, model structures and forecast time. Atmospheric Pollution Res.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2021.101168 (2021).

Zhou, Z., Zhou, X., Qi, H., Li, N. & Mi, C. J. E. S. w. A. Near miss prediction in commercial aviation through a combined model of grey neural network. 255, 124690 (2024).

Zhang, K., Thé, J., Xie, G. & Yu, H. Multi-step ahead forecasting of regional air quality using spatial-temporal deep neural networks: a case study of Huaihai Economic Zone. J. Clean. Prod.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123231 (2020).

Chang, Y. S. et al. An LSTM-based aggregated model for air pollution forecasting. Atmospheric Pollution Res. 11, 1451–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2020.05.015 (2020).

Abirami, S. & Chitra, P. Regional air quality forecasting using spatiotemporal deep learning. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125341 (2021).

Korkmaz, D., Acikgoz, H. & Yildiz, C. A. Novel short-term Photovoltaic Power forecasting Approach based on deep convolutional neural network. Int. J. Green Energy. 18, 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2021.1875474 (2021).

Yan, R. et al. Multi-hour and multi-site air quality index forecasting in Beijing using CNN, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and spatiotemporal clustering. Expert Syst. Appl.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114513 (2021).

Sayeed, A. et al. Using a deep convolutional neural network to predict 2017 ozone concentrations, 24 hours in advance. Neural Netw. 121, 396–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2019.09.033 (2020).

Ding, C., Wang, G., Zhang, X., Liu, Q. & Liu, X. A hybrid CNN-LSTM model for predicting PM2. 5 in Beijing based on spatiotemporal correlation. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 28, 503–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10651-021-00501-8 (2021).

Pak, U., Kim, C., Ryu, U., Sok, K. & Pak, S. A hybrid model based on convolutional neural networks and long short-term memory for ozone concentration prediction. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 11, 883–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-018-0585-1 (2018).

Faraji, M., Nadi, S., Ghaffarpasand, O., Homayoni, S. & Downey, K. An integrated 3D CNN-GRU deep learning method for short-term prediction of PM2. 5 concentration in urban environment. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155324 (2022).

Sharma, E. et al. Novel hybrid deep learning model for satellite based PM10 forecasting in the most polluted Australian hotspots. Atmos. Environ.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2022.119111 (2022).

Yang, F., Huang, G. & Li, Y. A New Combination Model for Air Pollutant Concentration Prediction: a Case Study of Xi’an. China Sustain.. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129713 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Air quality forecasting using a spatiotemporal hybrid deep learning model based on VMD-GAT-BiLSTM. Sci. Rep.. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68874-x (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Ash determination of coal flotation concentrate by analyzing froth image using a novel hybrid model based on deep learning algorithms and attention mechanism. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.125027 (2022).

de Medrano, R. & Aznarte, J. L. A spatio-temporal attention-based spot-forecasting framework for urban traffic prediction. Appl. Soft Comput.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106615 (2020).

Huang, S., Zhou, Q., Shen, J., Zhou, H. & Yong, B. Multistage spatio-temporal attention network based on NODE for short-term PV power forecasting. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.130308 (2024).

Ding, Y., Zhu, Y., Feng, J., Zhang, P. & Cheng, Z. Interpretable spatio-temporal attention LSTM model for flood forecasting. Neurocomputing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.04.110 (2020).

Qi, Y., Li, Q., Karimian, H. & Liu, D. A hybrid model for spatiotemporal forecasting of PM2. 5 based on graph convolutional neural network and long short-term memory. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.333

Li, D. et al. Residual neural network with spatiotemporal attention integrated with temporal self-attention based on long short-term memory network for air pollutant concentration prediction. Atmos. Environ.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120531 (2024).

Zhang, K. et al. Multi-step forecast of PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations using convolutional neural network integrated with spatial–temporal attention and residual learning. Environ. Int.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107691 (2023).

Kaur, R. & Ranade, S. K. Improving accuracy of convolutional neural network-based skin lesion segmentation using group normalization and combined loss function. Int. J. Inform. Technol. 15, 2827–2835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41870-023-01330-7 (2023).

Xie, C. et al. Short-term wind power prediction framework using numerical weather predictions and residual convolutional long short-term memory attention network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108543 (2024).

Tian, L. Multi-dimensional adaptive learning rate gradient descent optimization algorithm for Network Training in Magneto-Optical defect detection. Int. J. Netw. Dynamics Intell. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijndi.2024.100016 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. RCL-Learning: ResNet and convolutional long short-term memory-based spatiotemporal air pollutant concentration prediction model. Expert Syst. Appl.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118017 (2022).

Hu, L. et al. Single pd atoms anchored graphitic carbon nitride for highly selective and stable photocatalysis of nitric oxide. Carbon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2022.08.031 (2022).

Zhixiang, M., Cai, C., Xiangwei, M., Wei, L. & Chuanzhen, Z. Short-term effects of different PM2. 5 thresholds on daily all-cause mortality in Jinan, China. (2021). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-407621/v1

Sokhi, R. S. et al. Advances in air quality research – current and emerging challenges. Atmos. Chem. Phys.. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-4615-2022 (2022).

Gong, H., Hu, J., Rui, X., Wang, Y. & Zhu, N. J. W. R. Drivers of change behind the spatial distribution and fate of typical trace organic pollutants in fresh waste leachate across China. 263, 122170 (2024).

Yu, M., Masrur, A. & Blaszczak-Boxe, C. Predicting hourly PM(2.5) concentrations in wildfire-prone areas using a SpatioTemporal Transformer model. Sci. Total Environ.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160446 (2023).

Tong, J., Liu, C., Zheng, J. & Pan, H. J. E. A. o. A. I. Multi-sensor information fusion and coordinate attention-based fault diagnosis method and its interpretability research. 124, 106614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106614 (2023).

Lin, Y. C., Chi, W. J. & Lin, Y. Q. The improvement of spatial-temporal resolution of PM2.5 estimation based on micro-air quality sensors by using data fusion technique. Environ. Int.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105305 (2020).

Fuller, R. et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet. Health. 6, e535–e547. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00090-0 (2022).

Hu, Y., Ji, J. S. & Zhao, B. Deaths attributable to indoor PM2.5 in Urban China when Outdoor Air meets 2021 WHO Air Quality guidelines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 15882–15891. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c03715 (2022).

Guo, R., Zhang, Q., Yu, X., Qi, Y. & Zhao, B. A deep spatio-temporal learning network for continuous citywide air quality forecast based on dense monitoring data. J. Clean. Prod. 414, 137568 (2023).

Khan, S. D., Alarabi, L. & Basalamah, S. Toward Smart Lockdown: a Novel Approach for COVID-19 hotspots prediction using a deep hybrid neural network. Computers 9, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers9040099 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gang Chen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review editing. Shen Chen: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration. Dong Li: Methodology. Cai Chen: Software.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Chen, S., Li, D. et al. A hybrid deep learning air pollution prediction approach based on neighborhood selection and spatio-temporal attention. Sci Rep 15, 3685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88086-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88086-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A holistic air monitoring dataset with complaints and POIs for anomaly detection and interpretability tracing

Scientific Data (2025)

-

Air quality prediction using multi-source remote sensing data integration with hybrid deep learning framework

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Air Pollution Forecasting Using Genetic Algorithm and LSTM Deep Learning Technique

Aerosol Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Effective air pollution prediction using wavenet deep learning with Xgboost (1DCNN-BiLSTM-XgRC) for urban US embassies

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2025)