Abstract

To assess retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tears in eyes which underwent pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) for submacular hemorrhage (SMH) secondary to age-related macular degeneration and to investigate the prognostic factors of visual outcomes. This study was a retrospective, observational case series that included 24 eyes of 24 patients who underwent PPV with subretinal tissue plasminogen activator and air for SMH. RPE tears were investigated using spectral-domain or swept-source optical coherence tomography images with raster scan, combined confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope near-infrared images and color fundus photographs. Multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of visual outcome at month 3 and 6 after surgery. In 21 eyes out of 24 eyes (87.5%), RPE tear was detected in the posterior pole. Eight eyes (33.3%) had large RPE tears ( ≧ 1 disc diameter (DD)). Out of the 8 eyes, 5 eyes progressed fibrotic scars within 3 months despite successful SMH removal and showed decrease in their visual acuity (VA). The ratio of eyes with large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD) were significantly higher in eyes which had undergone anti-VEGF therapy within 3 months than in treatment-naïve eyes (71.4% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.048). The multiple regression analysis revealed that a small RPE tear (< 1DD) and treatment-naïve condition were associated with better VA at month 3 and 6. SMH within 3 months after anti-VEGF therapy might be accompanied by a large RPE tear. An RPE tear which was smaller than 1DD and treatment-naïve condition were associated with better prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Submacular hemorrhage (SMH) causes sudden visual loss in most patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). If left untreated, the visual prognosis for SMH is poor. In a submacular surgery trial, 90% of patients had visual acuity worse than 20/200 after 2 years1. Thick SMH interferes with retinal function and causes severe visual impairment through several mechanisms including blood toxicity from iron, hemosiderin, and fibrin overlying photoreceptors; clot retraction that may sheer and damage photoreceptors; and physical separation of photoreceptors from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells2,3.

As a surgical removal technique, pneumatic displacement combined with vitrectomy and subretinal tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is favored for large SMH ( ≧ 4 disc diameter) and the results have shown successful SMH displacement4,5,6,7,8,9. Prompt surgery, younger age, smaller hemorrhages, treatment-naive condition and absence of SMH recurrence have been reported as prognostic factors for better visual outcomes10,11,12. In some cases, however, visual outcomes are unfavorable due to the development of fibrotic changes in the macular area regardless of these factors. SMH precipitates the development of fibrotic component following large RPE tears13. The assessment of RPE tears is essential in the context of fibrotic scar formation after successful removal of the hemorrhage. Detecting RPE tears within the SMH area is, however, challenging because subretinal hemorrhage hides RPE tears on fundus photographs and makes it difficult to follow RPE line on optical coherence tomography (OCT). This may be one of the reasons why RPE tears in large SMH has not received much study. In this study, we investigated spectral-domain (SD) OCT or swept-source (SS) OCT images with raster scan, combined confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (cSLO) near-infrared images and color fundus photographs and detected RPE tears in SMH eyes with nAMD which underwent surgical removal. We also assessed the prognostic factors of better visual acuity for vitrectomy with subretinal tPA and air for SMH.

Methods

This study was a retrospective, observational case series that included 24 eyes of 24 patients at Toyama University Hospital. We treated them with 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with subretinal tPA for SMH involving the fovea secondary to nAMD between January 2013 and December 2022. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Toyama, and the procedures used conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

All patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmologic examinations, including measurement of the decimal best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular ressure, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, color fundus photography, and SD-OCT (RS-3000 Advance; NIDEK Co, Ltd, Aichi, Japan) or SS-OCT (DRI-OCT Toriton; Topcon Inc, Tokyo, Japan) in each visit. Hemorrhage thickness, the distance from the retinal pigment epithelium to the inner limiting membrane, was manually measured using the caliper function built into the linear measuring tool. Fluorescein angiography (FA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) were performed in 13 eyes to determine the subtypes of nAMD. In 11 eyes, PCV was determined by OCT-based criteria; sub-RPE ring-like lesion, en face OCT complex elevation, and sharp-peaked pigment epithelial detachment14. All patients were interviewed about anticoagulant use and the medical records were reviewed for prior anti-VEGF treatment and a history of photodynamic therapy.

All eyes underwent a standard pars plana vitrectomy with three 25-gauge ports. A 41-gauge cannula was used to inject 0.1 ml (corresponding to 8000 IU) monteplase (Cleactor; Eisai Co, Tokyo, Japan) into the subretinal space, creating a local retinal detachment encompassing part of the blood clot. Before each operation, OCT images were examined to select the injection point. The monteplase was injected at the point where the subretinal hemorrhage was thick enough. A fluid-air exchange (approximately 70–80%) was performed. Patients were asked to adopt face-down position for at least one hour following surgery, and then to sit up. They were asked to sleep on the side where the most blood was located, either on the left or the right side of the fovea. In phakic patients with significant cataracts, the treatment was combined with cataract surgery.

Postoperatively, all patients were followed for at least 6 months (typically at 1week, then 1, 3, and 6 months). SD-OCT or SS-OCT were performed at each visit. We treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents according to the doctors’ discretion when there was persistence of neovascular activity defined as any signs of exudation or new macular hemorrhage.

RPE tears were identified using SD- or SS-OCT images with raster scan, cSLO near-infrared images and color fundus photographs. Fundus autofluorescence was obtained sporadically and was not included in the analysis. We divided RPE tears into 2 groups according to whether the greatest linear diameter of them were longer than 1 disc diameter (DD) or not. On the images with adequate quality, the RPE tears were categorized based on the Sarraf’s grading system; Grade 1 tears were defined as < 200 μm, Grade 2 tears were between 200 μm and 1 DD, Grade 3 tears were > 1DD, and Grade 4 tears were defined as Grade 3 tears that involved the center of the fovea15. To detect small RPE tears which were not as obvious as large ones and were less likely to expand after surgery, the OCT characteristics were carefully monitored for signs such as; tented up PED and/or irregular PED at the level of RPE15. To confirm that the RPE tears were not complications during the surgery, all operation videos were reviewed, and we verified that the locations of the RPE tears were at a distance from monteplase injection points.

The degree of blood displacement was determined with fundus photographs and graded as complete, partial or no displacement. Complete displacement was defined as no blood or only a scant amount of blood within 1 DD of the foveal center; partial displacement was defined as blood under the fovea that obscured the retinal pigment epithelium but did not cause clinically visible elevation of the retina.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using JMP statistical discovery software (version 17; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The decimal BCVA was converted to a logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis. The changes of mean BCVA were evaluated with T-test. To compare the ratio of eyes with large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD) between treatment-naïve eyes and the eyes which had undergone anti-VEGF treatment within 3 months, Pearson’s chi-square test was performed. The associations between the clinical characteristics and visual acuity at months 3 and 6 were evaluated using univariate analysis. The characteristics with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multiple regression analysis, and the selection of variables in the final model was performed by forward-backward stepwise selection method. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

The characteristics of the 24 eyes of 24 patients are presented in Table 1. All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 months (mean ± SD, 44.8 ± 39.2 months). The mean age was 75.3 ± 7.9 years, and 14 patients (58%) were men. Six patients were taking anticoagulant medication (aspirin or other platelet inhibitor and/or warfarin). Surgery was performed an average of 5.4 ± 5.1 days after the onset of symptoms. Fourteen eyes (58.3%) were treatment naïve. Eight eyes (33.3%) had anti-VEGF treatment within 3 months before onset. One eye had anti-VEGF therapy 4 months before onset and one eye had history of combination therapy using anti-VEGF and half-time photodynamic therapy (PDT) 3 years before the onset. The hemorrhage was completely displaced from the fovea in 22 eyes (91.7%) and partially displaced in 2 eyes (8.3%). Anti-VEGF therapies were performed for 10 patients (41.7%) within 1 month after surgery. Eighteen patients (75%) underwent anti-VEGF therapy within 6 months following surgery (Table 1).

RPE tears

RPE tears were found in 21 eyes (87.5%) before and/or after surgery; 3 eyes had obvious RPE tears before operation, 9 eyes had possible RPE tears preoperatively which were confirmed postoperatively, and RPE tears in 9 eyes were detected after the operation. Eight eyes (33.3%) were affected by large RPE tears which were larger than 1 DD. Five of the 8 eyes developed fibrotic scars in the macular area within 3 months after surgery (Fig. 1). Thirteen eyes out of 24 eyes (54.2%) had RPE tears which were smaller than 1DD, and none of the eyes developed subretinal fibrosis regardless of their locations (Fig. 2). Out of the 8 eyes which underwent anti-VEGF therapy within 3 months before onset, 5 eyes had RPE tears which were larger than 1DD and 2 eyes had grade 2 RPE tears; RPE tear was undetectable in the posterior pole in 1 eye. The ratio of eyes with large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD) were significantly higher in eyes which had undergone anti-VEGF therapy within 3 months than in treatment-naïve eyes (71.4% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.048).

A 77-year-old male patient who underwent anti-VEGF therapy 12 days before SMH onset. (a and b), before surgery; (c and d), 8 days after surgery; (e and f), 3 months after surgery. (b and d), The OCT images show RPE tear (white double-headed arrow) which was larger than 1DD before surgery (c) and it expanded after surgery (b). (c), Fundus photograph shows successful removal of SMH and large RPE tear (arrowheads). (e and f), A fibrotic scar had developed within 3 months after surgery. Visual acuity decreased from 0.82 at baseline to 1.4 at month 3.

A 67-year-old male patient who was treatment-naïve. (a), before surgery; (b, c, and d), 3 weeks after surgery; (e and f), 3 months after surgery; (g and h), 6 months after surgery. (b, c) Fundus photograph and combined cSLO near-infrared image show grade 2 RPE tears (arrow heads). (d), The OCT image shows tented up PED at the level of RPE (white arrow). (d and f), The OCT images show an RPE tear (white double-headed arrow). (h), OCT image shows the attenuated RPE line (arrow) and the outer retina without fibrotic scar.

Visual acuity

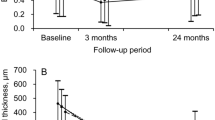

The mean visual acuity (n = 24) was 1.09 ± 0.60 before surgery (baseline); 0.80 ± 0.54 at month 1 (p = 0.037); 0.76 ± 0.70 at month 3 (p = 0.12); 0.80 ± 0.73 at month 6 (p = 0.19). In eight eyes with large RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD), the mean visual acuity did not show remarkable improvement after surgery; 1.28 ± 0.49 at baseline; 1.21 ± 0.49 at month 1 (p = 0.86); 1.38 ± 0.49 at month 3 (p = 0.76); 1.49 ± 0.45 at month 6 (p = 0.38). On the other hand, in 13 eyes with small RPE tears (< 1DD), the mean visual acuity improved significantly; 0.96 ± 0.46 at baseline; 0.60 ± 0.46 at month 1 (p = 0.0033); 0.56 ± 0.62 at month 3 (p = 0.025); 0.56 ± 0.65 at month 6 (p = 0.039). In the 13 eyes, 6 eyes had RPE tears within 1DD of the foveal center. The mean visual acuity in these eyes also showed remarkable improvement after surgery; 0.95 ± 0.26 at baseline; 0.69 ± 0.48 at month 1 (p = 0.19); 0.33 ± 0.29 at month 3 (p = 0.0078); 0.41 ± 0.36 at month 6 (p = 0.043) (Fig. 3). In the other 7 eyes, visual acuity significantly improved after surgery; 0.97 ± 0.58 at baseline; 0.53 ± 0.44 at month 1 (p = 0.0065); 0.45 ± 0.57 at month 3 (p = 0.013); 0.38 ± 0.60 at month 6 (p = 0.008) (Fig. 3).

Changes of mean values of logMAR in eyes with small RPE tears (< 1DD). The mean visual acuity improved in both groups. Solid line, eyes with RPE tears (< 1DD) which were within 1 DD of the foveal center (baseline, month 1, 3 and 6; 0.95 ± 0.26, 0.69 ± 0.48, 0.33 ± 0.29, 0.41 ± 0.36; p = 0.19, p = 0.078, p = 0.0043). Dotted line, eyes with RPE tears (< 1DD) which were not within 1DD of the foveal center. (Baseline, month 1, 3 and 6; 0.97 ± 0.58, 0.53 ± 0.44, 0.45 ± 0.57, 0.38 ± 0.60; p = 0.0065, p = 0.013, p = 0.008)

In the univariate analysis, BCVA at month 3 correlated with age (r = 0.48, p = 0.025), oral anticoagulant intake (r = 0.43, p = 0.048), duration between onset and surgery (r = 0.54, p = 0.012), size of the RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD) (r=-0.57, p = 0.011), location of the RPE tear (extended into 1 DD of the foveal center) (r=-0.45, p = 0.040), SMH recurrence within 3 months after surgery (r=-0.62, p = 0.0023) and treatment-naïve condition (r = 0.53, p = 0.012); in the multiple regression analysis, it correlated with size of the RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD) (β=-0.42, p = 0.020) and treatment-naïve condition (β = 0.38, p = 0.042)(Table 2). In the univariate analysis, BCVA at month 6 correlated with age (r = 0.53, p = 0.011), duration between onset and surgery (r = 0.49, p = 0.023), size of the RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD) (r=-0.61, p = 0.0056), location of the RPE tear (extended into 1 DD of the foveal center) (r=-0.51, p = 0.026), SMH recurrence within 6 months after surgery (r=-0.46, p = 0.032) and treatment-naïve condition (r = 0.52, p = 0.014) ; in the multiple regression analysis, it was significantly associated with size of the RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD) (β=-0.52, p = 0.0029) and treatment-naïve condition (β = 0.35, p = 0.047) (Table 3).

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications were observed in 10 patients (41.7%) (Table 4). The most frequent complications were recurrent submacular hemorrhages (6 patients, 25.0%). Macular holes were found in 2 patients (8.3%), and a vitreous hemorrhage, a retinal detachment and a new formation of a grade 3 RPE tear at month 3 were observed in one patient each (4.2%).

Discussion

The present study revealed that RPE tears larger than 1 DD were one of the prognostic factors for poor visual acuity due to fibrotic scar formation despite successful SMH removal after surgery. Physicians should be mindful of the possible existence of large RPE tears within the hemorrhage area especially in eyes which have undergone anti-VEGF injections within 3 months. In eyes with small RPE tears, the visual prognosis was better regardless of the locations. Our study reconfirmed the importance of assessing RPE tears in SMH patients before and after surgery. Treatment-naïve condition was also associated with better visual prognosis.

There are two forces which are thought to be responsible for the formation of RPE tears: tractional forces from macular neovascularization (MNV) contraction and hydrostatic forces from the fluid in the RPE detachment16,17. The relative contribution of each force varies from eye to eye, resulting in different morphologic characteristics of the RPE tears. Previous studies revealed that tractional forces from MNV shrinkage occur in response to anti-VEGF therapy. In the present study, the ratio of eyes with large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD) were significantly higher in patients who had received ant-VEGF injections within 3 months than in patients who were treatment-naïve (71.4% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.048). This result indicates that tractional forces following anti-VEGF therapy were largely responsible for the large RPE tear formation. In addition, the large hemorrhage originating in MNV might also enlarge the RPE tear because it expands the pigment epithelial detachment (PED), which exerts a greater tangential stress on the RPE. A large hemorrhage also results in a smaller ratio of MNV size to PED size, which reportedly has greater tendency for tear development because tangential stress on the RPE is focused on a well-defined compartment of PED lesions18,19. On the other hand, in treatment-naïve eyes, 9 eyes out of 13 eyes had small RPE tears (< 1DD). In those eyes, hydrostatic forces might have been more responsible for the RPE tear formation than tractional forces.

As the management for RPE tears secondary to anti-VEGF treatment in nAMD, additional anti-VEGF treatments are thought to stabilize or improve visual acuity with less progression of RPE tears, reducing fibrosis and lowering risk of a large disciform scar9,10,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Sarraf D and colleagues reported that lower grade RPE tears have resulted in a better visual improvement with anti-VEGF therapy and are less likely to develop subretinal fibrosis or disciform scars15. In previous cases, patients were treated with anti-VEGF agents when there was a persistence or occurrence of neovascular activity. Thirteen eyes had RPE tears which were smaller than 1DD, and none of the eyes developed subretinal fibrosis; visual acuity improved in those cases except for one case which experienced repeated submacular bleeding. Our study was consistent with the previous reports and showed that proper anti-VEGF treatment enables eyes with small RPE tears (< 1DD) to improve visual function even if the tear was within 1DD of the foveal center owing to the avoidance of fibrotic scar formation. In large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD), however, anti-VEGF therapy could barely suppress the spread of fibrotic scars; 5 of 8 eyes with large RPE tears ( ≧ 1DD) showed poor visual outcome following strong fibrotic scarring that emerged within 3 months after surgery. New treatments for large RPE tears are key to prevent the progression of fibrosis.

Consistent with previous studies, treatment-naïve condition correlated with better visual outcome in the present study. Tingkun S and colleagues considered that treatment-naïve eyes were healthier and more resistant to damage from hemorrhage than eyes with history of anti-VEGF treatments10. Our study revealed that the ratio of eyes with large RPE tear ( ≧ 1DD) in treatment-naïve eyes was significantly lower than in eyes with anti-VEGF treatment within 3 months, which might be also the reason for the better prognosis in treatment-naïve eyes.

The retrospective nature and small sample size potentially limit the conclusions of this study. Further investigations with larger samples are warranted to confirm our observations. Assessing preoperative RPE tears was mainly performed using SD- or SS-OCT images with raster scan because hemorrhage hid the details of fundus photographs. The features of SMH also diminish OCT image quality and could cause an overestimation or an underestimation of the grade of RPE tears. Some limitations were intrinsic to the high percentage of PCV patients in this study (87.5%) because SMH is more common in PCV than other nAMD subtypes. The frequency of RPE tears can differ among nAMD subtypes. We also cannot deny the possibility; the RPE tears which we detected after surgery could have been progressed or occurred during the vitrectomy. Despite these limitations, we believe our findings indicate that careful study of the RPE tears that exist within the SMH area will lead to a better prediction of visual prognosis and better care for SMH patients in real-life clinical practice.

In conclusion, RPE tears which were larger than 1 DD caused poor visual outcomes due to fibrotic scar formation despite successful SMH removal. Large SMH within 3 months after anti-VEGF therapy might be accompanied by large RPE tears. With postoperative anti-VEGF therapy, small RPE tears had better visual prognosis regardless of their locations. Treatment-naïve condition was also associated with better visual prognosis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bressler, N. M. et al. Surgery for hemorrhagic choroidal neovascular lesions of age-related macular degeneration: Ophthalmic findings: SST report no. 13 Ophthalmol. 111, 1993–2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.023 (2004).

Glatt, H. & Machemer, R. Experimental subretinal hemorrhage in rabbits. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 762–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(82)90301-4 (1982).

Hochman, M. A., Seery, C. M. & Zarbin, M. A. Pathophysiology and management of subretinal hemorrhage. Surv. Ophthalmol. 42(3), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00089-1 (1997).

de Jong, J. H. et al. Intravitreal versus subretinal administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator combined with gas for acute submacular hemorrhages due to age-related macular degeneration: An exploratory prospective study. Retina 36, 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000954 (2016).

Ehlers, J. P. et al. Intrasurgical assessment of subretinal tPA injection for submacular hemorrhage in the PIONEER study utilizing intraoperative OCT. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 46, 327–332. https://doi.org/10.3928/23258160-20150323-05 (2015).

van Zeeburg, E. J., Cereda, M. G. & van Meurs, J. C. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, vitrectomy, and gas for recent submacular hemorrhage displacement due to retinal macroaneurysm. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 251, 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-012-2116-3 (2013).

Chang, W. et al. Management of thick submacular hemorrhage with subretinal tissue plasminogen activator and pneumatic displacement for agerelated macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 157, 1250–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2014.02.007 (2014).

Kimura, S. et al. Submacular hemorrhage in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy treated by vitrectomy and subretinal tissue plasminogen activator. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 159, 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.020 (2015).

Jeong, S., Park, D. G. & Sagong, M. Management of a submacular hemorrhage secondary to age-related macular degeneration: A comparison of three treatment modalities. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103088 (2020).

Shi, T. et al. Vitrectomy with subretinal injection of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for submacular hemorrhage with or without vitreous hemorrhage. Retina 44(7), 1188–1195. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000004093 (2024).

Miki, M. et al. Predictors of 3-month and 1-year visual outcomes after vitrectomy with subretinal tissue plasminogen activator injection for submacular hemorrhage. Retina 43(11), 1971–1979. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003885 (2023).

González-López, J. J. et al. Vitrectomy with subretinal tissue plasminogen activator and ranibizumab for submacular haemorrhages secondary to age-related macular degeneration: Retrospective case series of 45 consecutive cases. Eye (Lond.) 30, 929–935. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.65 (2016).

Romano, F. et al. Optical coherence tomography features of the repair tissue following RPE tear and their correlation with visual outcomes. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 5962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85270-x (2021).

Cheung, C. M. G. et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: Consensus nomenclature and non-indocyanine green angiograph diagnostic criteria from the Asia-Pacific ocular imaging society. PCV Workgr. Ophthalmol. 128(3), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.006 (2021).

Sarraf, D. et al. A new grading system for retinal pigment epithelial tears. Retina 30(7), 1039–1045. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf366 (2010).

Ie, D. et al. Microrips of the retinal pigment epithelium. Arch. Ophthalmol. 110(10), 1443–1449. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1992.01080220105030 (1992).

Clemens, C. R. & Eter, N. Retinal pigment epithelium tears: Risk factors, mechanism and therapeutic monitoring. Ophthalmologica 235(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439445 (2016).

Chan, C. K. et al. Optical coherence tomography-measured pigment epithelial detachment height as a predictor for retinal pigment epithelial tears associated with intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Retina 30(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181babda5 (2010).

Clemens, C. R. et al. Prediction of retinal pigment epithelial tear in serous vascularized pigment epithelium detachment. Acta Ophthalmol. 92(1), e50–e56. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.12234 (2014).

Ersoz, M. G. et al. Retinal pigment epithelium tears: Classification, pathogenesis, predictors, and management. Surv. Ophthalmol. 62(4), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.03.004 (2017).

Cunningham, E. T. Jr et al. Incidence of retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal ranibizumab injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 118(12), 2447–2452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.026 (2011).

Fine, H. F., Prenner, J. L. & Roth, D. B. Long-term followup of spontaneous retinal pigment epithelium tears in age-related macular degeneration treated with anti-VEGF therapy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 21(1), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.5301/ejo.2010.2285 (2011).

Coco, R. M. et al. Retinal pigment epithelium tears in age-related macular degeneration treated with antiangiogenic drugs: A controlled study with long follow-up. Ophthalmologica 228(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338730 (2012).

Moreira, C. A., Arana, L. A. & Zago, R. J. Long-term results of repeated anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in eyes with retinal pigment epithelial tears. Retina 33(2), 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e318263d139 (2013).

Sarraf, D., Joseph, A. & Rahimy, E. Retinal pigment epithelial tears in the era of intravitreal pharmacotherapy: Risk factors, pathogenesis, prognosis and treatment (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 112, 142–159 (2014).

Doguizi, S. & Ozdek, S. Pigment epithelial tears associated with anti-VEGF therapy: Incidence, long-term visual outcome, and relationship with pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration. Retina 34(6), 1156–1162. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000056 (2014).

Durkin, S. R. et al. Change in vision after retinal pigment epithelium tear following the use of anti-VEGF therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 254(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-015-2978-2 (2016).

Heimes, B. et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tear and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in exudative age-related macular degeneration: Clinical course and long-term prognosis. Retina 36(5), 868–874. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000823 (2016).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Tomoko Ueda-Consolvo, Syogo Takahashi, Toshihiko Oiwake, Masaaki Ishida, Shuichiro Yanagisawa and Atsushi Hayashi. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tomoko Ueda-Consolvo and revised by Atsushi Hayashi. The revised manuscript was written by Tomoko Ueda-Consolvo and revised by Atsushi Hayashi. Syogo Takahashi and Toshihiko Oiwake prepared the figures and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Toyama, and the procedures used conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figure(s) 1a-f, and 2 a-h.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda-Consolvo, T., Takahashi, S., Oiwake, T. et al. Assessment of retinal pigment epithelium tears in eyes with submacular hemorrhage secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep 15, 3606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88128-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88128-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Macular hole caused by intense pulsed light: a case report

BMC Ophthalmology (2025)