Abstract

Smoking is a major cause of cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. However, the role of age at smoking initiation in cardiovascular risk has not been fully established. We selected 9,295,979 Korean adults without preexisting cardiovascular diseases who underwent health screening in 2009. The association of age at initiation with incident MI, stroke, MI or stroke, and all-cause mortality was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models stratified or adjusted for total pack-years (PY). Among the 3,724,368 smokers, 876,740 smokers (23.5%) started before age 20, and 75,299 smokers (2.0%) had age at initiation < 15. Over a nine-year follow-up, ≥ 20 PY smokers with age at initiation < 20 had the highest risks of MI (adjusted hazard ratio (HR), 2.43; 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 2.35–2.51), stroke (HR 1.78, 95% CI 1.73–1.83), MI or stroke (HR 2.00, 95% CI 1.96–2.04), and death (HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.79–1.85) relative to nonsmokers, significantly higher than in ≥ 20 PY smokers with initiation age ≥ 20. Earlier age at initiation was associated with increasing PY-adjusted risks of each outcome (p for trend < 0.001 each). Age at initiation also had significant interactions with total PY for each outcome (p < 0.001 each), with PY-dependent risk increases accentuated by earlier initiation. Early age at smoking initiation is associated with increased risks of MI and stroke. Focused smoking prevention measures may be warranted for both adolescents and young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tobacco smoking is a leading cause of preventable human death1,2. Despite public health efforts toward smoking cessation, tobacco use accounted for 8.7 million deaths in 2019, or 15% of all deaths worldwide3. Smoking also remains the single risk factor responsible for the most number of deaths in South Korea, estimated to have caused 20% of all deaths as of 20204. Cardiovascular diseases account for the most number of tobacco-related deaths globally3, with strong evidence of causal relationship between smoking exposure and risks of coronary heart disease and stroke1. Cigarette smoke has been shown to induce atherogenesis through a multitude of mechanisms that include endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, promotion of thrombosis, and alteration of lipid metabolism1,5.

Large epidemiological studies have provided ample clinical evidence suggesting greater pack-years of smoking exposure results in higher risks of coronary heart disease and stroke6,7,8. Use of low-tar cigarettes appears to reduce cardiovascular risk, further supporting a dose-response relationship9. However, this relationship appears to be nonlinear, with higher than expected cardiovascular risk in light smokers who consume as little as one cigarette per day6,10,11. As pack-years alone appear insufficient for modeling the effects of smoking, there have been calls to consider both duration and intensity in assessment of smoking exposure12,13.

Age at initiation is another indicator of smoking status with potential health consequences independent of total pack-years. Young age at smoking initiation has been linked to increased adult morbidity and mortality in multiple epidemiologic studies14,15,16. Studies on secondhand smoke have shown that children are particularly vulnerable to cigarette smoke exposure given their higher respiratory rate and likely lower capacity to metabolize nicotine compared to adults17. The potential mechanisms in which smoking can raise cardiovascular risks in the young include not only direct biological effects on the vasculature but also indirect means such as tendencies toward impulsivity and vulnerability to substance dependence that can be elicited by the effects of nicotine on the developing brain17,18.

Nevertheless, characterizing the independent health effects of age at smoking initiation has been challenging, and its influence on cardiovascular risks has not been fully established. Multiple studies reported higher risks of cardiovascular disease and related mortality in smokers with earlier age at initiation15,19,20,21,22, while some did not find significant associations between age at initiation and cardiovascular outcomes23,24. While a recent cohort study demonstrated a significant trend of increasing stroke risk with younger age at smoking initiation over a ten-year follow-up25, no such association with stroke was identified in a birth cohort followed up for five decades26. Some of these apparent inconsistencies could be explained by low numbers of study outcomes in the cohort23,26or local trends as seen in one study featuring data from Cuba, a tobacco-producing country with high adolescent smoking rates19. Differences in study population selections, definitions of early-onset smokers, and considerations for confounding variables may have also contributed to the inconsistent results from studies based on United States data14,15,22,23,24. Since randomized trials and prospective cohort designs on this topic are not practical given the ethical issues and the need for a large study population with extended follow-up, there is a need for well-designed retrospective studies despite the inherent limitations from recall bias and unmeasured confounding factors. Additional large-scale evidence that can separate the effects of smoking age, duration, and intensity as well as adequately adjust for confounders is needed to ascertain the relationship between age at smoking initiation and cardiovascular diseases, which could have medical as well as social implications with regards to tobacco prevention and control measures.

In this study, we aimed to further investigate the role of early age at smoking initiation on the risk of cardiovascular diseases. We hypothesized that earlier age at initiation would be an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause death. To mitigate the inevitable issue of multicollinearity and potential effect modification among age at initiation, baseline age, and total pack-years, we based our analyses on a large population-wide cohort that allowed stratified analyses according to total pack-years of smoking exposure. This cohort, composed of nine million Korean adults who participated in the National Health Screening Program, also contains ample demographic, laboratory, and questionnaire data that can be utilized to adjust for the effects of major cardiovascular risk factors. Therefore, the present study harnesses the power of a population-based cohort to elucidate the significance of early age at smoking initiation as a potential independent risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. E-2001-112-1096). The need for informed consent was waived given the retrospective design based on anonymized NHID data. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data source

This study utilized data from the Korean National Health Information Database (NHID). NHID is a nationwide database managed by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), which covers 97% of the Korean population under a mandatory single-payer system27. In addition to claims data and demographic information, the database includes information from the National Health Screening Program (NHSP), an NHIS-sponsored annual or biennial general health checkup program for adults aged 20 or above. The screening includes anthropometric measurements, laboratory tests, and self-administered questionnaires. An English translation of the questionnaires has been made available previously28.

Subject selection and definition of smoking status

A flowchart of the subject selection process is provided in Fig. 1. From the NHID, we identified 10,585,844 adults who participated in the NHSP in 2009. We excluded individuals with missing information as well as those with a preexisting diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or end-stage kidney disease based on the 10th International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes documented between January 1, 2002, and the day of the 2009 NHSP checkup for each subject to study incident outcomes.

Based on self-reported smoking behavior from NHSP questionnaires, we extracted age at smoking initiation, cumulative smoking exposure (in pack-years, PY), and status as former or current smoker. Smoking status was defined as a categorical variable according to age at smoking initiation and total PY for the main analyses. Status as former or current smoker was used to further subdivide smoker categories in a sensitivity analysis. As an alternate means to address the issue of multicollinearity between age at initiation and total PY, we also defined a new exposure variable, total PY divided by age at initiation, and categorized smokers into quartiles for an additional analysis.

Covariate definitions

Baseline waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and dipstick urine albumin measurements were collected from the NHSP. Information on alcohol consumption and physical activity were extracted from NHSP questionnaires. Alcohol intake frequency and intensity were converted into grams per day equivalent to categorize subjects into nondrinkers, mild drinkers (< 30 g/day), and heavy drinkers (≥ 30 g/day). Physical activity was classified as regular exercise (moderate-intensity physical activity ≥ 5 days/week or vigorous-intensity physical activity ≥ 3 days/week) or no regular exercise. Low income was defined as annual income in the lowest quartile, determined from NHIS premiums. Presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia was determined based on ICD-10 codes and relevant medication prescription history in the NHID. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the harmonizing criteria based on NHSP measurements29.

Study outcomes and follow-up

The outcomes were newly diagnosed MI, stroke, MI or stroke, or all-cause mortality. MI was defined by hospital admission with ICD-10 codes I21 or I22, and stroke was defined by admission with ICD-10 code I63 or I64 from the NHID records. The follow-up period was from 1 day after the 2009 NHSP checkup until occurrence of each study outcome (MI, stroke, death), date of death, or December 31, 2018, whichever was the earliest.

Statistical analysis

For baseline characteristics, continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was applied to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) according to smoking status for each study outcome: MI, stroke, MI or stroke, or all-cause mortality. Results from unadjusted model (Model 1) were presented along with results from multivariate model adjusted for age and sex only (Model 2) and model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (kg/m2), metabolic syndrome (yes or no), estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73m2), dipstick urine albumin (absent or trace, 1+, or above 1+), alcohol consumption (none, mild, or heavy), physical activity (regular exercise or not), and low-income status (yes or no). The model was also adjusted for total smoking exposure (PY) when it was not used to define smoker subgroups. Sensitivity analyses were performed by applying different threshold ages and PY in defining smoking status.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study subjects according to smoking status

Of the 9,295,979 subjects, 3,724,368 (40.1%) had smoking history, among whom 876,740 (9.4% of all subjects and 23.5% of all smokers) had started smoking before age 20 (Table 1). The mean follow-up period for each subgroup ranged from 8.8 to 9.3 years until MI or stroke and from 9.0 to 9.3 years until all-cause death. Males comprised 94.3% of smokers, with 99.5% male dominance in ≥ 20 PY smokers who started smoking before age 20, while only 27.8% of nonsmokers were male. A greater proportion of smokers was active drinkers (75.0%) relative to nonsmokers (31.6%), and a lower proportion of smokers was low-income individuals (15.4%) compared to nonsmokers (22.4%). Among smokers, ≥ 20 PY smokers had a higher mean age than < 20 PY smokers: 47.2 versus 31.3 in early smokers and 54.6 versus 43.3 in late smokers. Prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome were higher in ≥ 20 PY smokers than in < 20 PY smokers and higher in smokers with age at initiation ≥ 20 compared to those with age at initiation < 20.

Cardiovascular diseases and mortality according to age at initiation and total pack-years

We calculated risks of MI, stroke, MI or stroke, and all-cause mortality according to smoking status (Table 2; Fig. 2). When adjusted for clinical covariates including age and sex, all smoker subgroups showed significantly elevated risks of cardiovascular events and mortality. Smokers with age at initiation < 20 with ≥ 20 PY exposure had the highest increase in risk for MI (HR 2.43, 95% CI [2.35–2.51]), stroke (HR 1.78 [1.73–1.83]), and MI or stroke (HR 2.00 [1.96–2.04]) relative to nonsmokers. While ≥ 20 PY smokers with age at initiation ≥ 20 also had elevated risks of MI (HR 1.82 [1.78–1.86]), stroke (HR 1.38 [1.36–1.41]), MI or stroke (HR 1.52 [1.50–1.54], and all-cause death (HR 1.41 [1.39–1.42]), they were significantly lower than the risk increase observed in smokers who started before age 20 (Supplementary Table S1). As for < 20 PY smokers, those with age at initiation < 20 did not have significant differences in adjusted relative risks of MI and stroke compared to those with age at initiation ≥ 20. While the relative risk of all-cause death was the lowest in < 20 PY smokers with smoking initiation age < 20 (HR 0.24 [0.23–0.25]) in the unadjusted model, they were the highest (HR 2.06 [2.00–2.13]) in this subgroup under our multivariate model. Higher relative risks for MI, stroke, and all-cause death were observed in smokers with age at initiation < 20 compared to those who started at age ≥ 20 regardless of the choice of threshold for defining high total exposure among 30, 40, and 50 PY, and the differences in risks were significant for subjects both below and above the PY threshold (Supplementary Table S1, S2).

Cumulative incidence of study outcomes according to age at smoking initiation and total pack-years under a multivariate model. The x-axes show time in years. The y-axes show the incidence probability of MI, stroke, MI or stroke, or all-cause death adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, metabolic syndrome, estimated glomerular filtration rate, dipstick urine albumin, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and low-income status. (MI = myocardial infarction).

Smokers were additionally classified into smoking intensity quartiles based on cumulative PY divided by age at initiation. Smokers in higher quartiles, which correspond to lower ages at initiation and higher total PY, showed greater risk of MI, stroke, and death, with the highest risk observed in Quartile 4 for MI (HR 2.09 [2.04–2.14]), stroke (HR 1.55 [1.52–1.57]), and death (HR 1.57 [1.56–1.59]) (Fig. 3A).

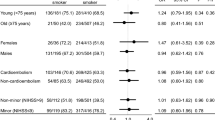

Cardiovascular diseases and mortality with different ages at smoking initiation

We next analyzed study outcomes according to multiple categories of age at smoking initiation defined between ages 15 and 30 (Fig. 3B). In a multivariate model additionally adjusted for total smoking exposure, earlier age at initiation was significantly associated with increased risk of MI, stroke, MI or stroke, and death, with p for trend < 0.001 for each outcome. Those who reported starting smoking before age 15 had the highest risk of MI or stroke (HR 1.13 [1.07–1.18]), stroke (HR 1.18 [1.11–1.25]), and death (HR 1.19 [1.15–1.23]), significantly greater than the respective risks seen in those who started at age 20–25. While not significant in the same comparison, relative risk of MI in smokers with start age < 15 (HR 1.04 [0.97–1.12]) was significantly greater than that of late smokers who started at age ≥ 30 (HR 0.81 [0.78–0.84]).

Risks of study outcomes according to age at smoking initiation adjusted for total pack-years. (A) Risks of study outcomes according to total pack-years divided by age at smoking initiation. All smokers were divided into quartiles of total pack-years divided by age at smoking initiation, with Q4 being the highest. (B) Risks of study outcomes according to age at smoking initiation under a multivariate model additionally adjusted for total pack-years. Each interval of age presented includes the lower limit and excludes the upper limit. Smokers with age at initiation between 17 and 20 were set as reference. The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, metabolic syndrome, estimated glomerular filtration rate, dipstick urine albumin, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and low-income status. (N = number of subjects, Q = quartile, MI = myocardial infarction, HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval).

Interaction between age at initiation and total pack-years in study outcomes

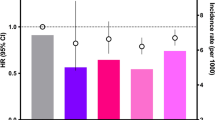

When interactions between age at smoking initiation and total PY of exposure were examined, significant interactions were found in relative risks of MI, stroke, MI or stroke, and death in the multivariate model (p for interaction < 0.001 for each) (Fig. 4). There was a trend toward a greater increase in adjusted PY-dependent risks of MI, stroke, and MI or stroke in subjects with earlier ages at smoking initiation. Smokers with age at initiation < 20 had the highest elevation in risk of MI or stroke for ≥ 20 PY smokers (HR 2.43 [2.26–2.60]) relative to < 10 PY smokers, and the lowest corresponding relative risk (HR 1.26 [1.23–1.29]) was seen in subjects who started smoking at age ≥ 30. Meanwhile, adjusted relative risks of all-cause death did not show a consistent trend aside from a trend of PY-dependent increase in risk for smokers with age at initiation ≥ 30.

Stratified risks of study outcomes according to age at smoking initiation and total pack-years under a multivariate model. Each interval presented includes the lower limit and excludes the upper limit. The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, metabolic syndrome, estimated glomerular filtration rate, dipstick urine albumin, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and low-income status. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals were presented as error bars. (MI: myocardial infarction, IR: incidence rate).

Cardiovascular diseases and mortality in different subgroups

We further explored the interactions between different clinical covariates and the risk of MI, stroke, and death according to age at smoking initiation and total exposure (Supplementary Table S3). The interactions observed were statistically significant with p < 0.001 for all variables examined (age, sex, BMI, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, physical activity, and alcohol consumption) except for physical activity in stroke (p = 0.03) and alcohol consumption in all-cause death (p = 0.22). Nevertheless, the relative risks of MI, stroke, and MI or stroke were consistently the highest in smokers with age at initiation < 20 with ≥ 20 PY exposure. In addition, when smokers were subcategorized based on their current smoking status, both former and current smokers with ≥ 20 PY smoking history with age at initiation < 20 had the highest increases in risk for MI, stroke, and MI or stroke within their categories (Supplementary Table S4). Even in those who initiated smoking between age 25–30, their cardiovascular or mortality risk was significantly higher than those who started smoking at ≥ 30 years old.

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based study, young age at smoking initiation was consistently associated with elevated risks of myocardial infarction and stroke. Significant increase in cardiovascular risk with early smoking initiation was observed at all ranges of total exposure above 20 PY, in all covariate subgroups, and in both former and current smokers. Moreover, PY-dependent increase in cardiovascular risk among smokers was amplified in those with lower ages at initiation, and earlier smoking initiation under age 30 was associated with progressively higher cardiovascular risks and all-cause mortality.

The main strength of our study is the utilization of a large nationwide cohort of nearly 10 million subjects with detailed information on other major cardiovascular risk factors. This setup allowed us to adjust for relevant covariates and perform stratified and interaction analyses to better separate the health effects of age at initiation from total PY over a wide range of ages at initiation. In comparison, previous studies that did not report significant associations between age at smoking initiation and cardiovascular risks appear to have lacked the cohort size and diversity needed to demonstrate these associations. One study evaluated cardiovascular mortality in over 100,000 women, but as the cohort had fewer than 2,000 total cardiovascular deaths23, the cohort size may have been insufficient to distinguish the effects of age at initiation. Another five-decade follow-up study did not find any associations between age at initiation and incident stroke, but the subjects notably had a very narrow range of age at initiation at 16.7 ± 0.2 years26. Our diverse cohort featured a greater range of age at initiation that allowed us to more effectively examine the relationship between age at smoking initiation and cardiovascular risks, which was important not only in childhood but also in early adulthood.

Another strength is that we could demonstrate the high cardiovascular risks associated with high PY of smoking were accentuated in those who initiated smoking at earlier ages. Indeed, we observed significant and consistent interactions between age at initiation and total pack-years with respect to cardiovascular outcomes. In early-onset smokers, the relative risk of MI and stroke from ≥ 20 PY smoking was more than doubled relative to smoking < 10 PY total after adjustment for baseline age. While it is impossible to fully separate the effects of age at initiation and smoking duration30, this interaction suggests the possibility that the same quantity of smoking may raise relative cardiovascular risk to a greater extent when exposed at an earlier age.

These apparent synergistic effects of age at initiation and pack-years of smoking intensity are consistent with an enhanced biological vulnerability to smoking in the early years of life. Pathological evidence of atherosclerosis has been found in early childhood, even though certain tribes whose living conditions are free of cardiovascular risk factors do not develop cardiovascular diseases, suggesting a chronic yet modifiable course of atherosclerosis that starts before adolescence31,32. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors including smoking have significant associations with adult cardiovascular disease risks as well as increases in carotid intima-media thickness, a measure of subclinical atherosclerotic progression33,34. Furthermore, early initiation of smoking may imply the possibility of stronger addiction to the harmful social behavior. In line with these findings, our analysis supports age- and intensity-dependent effects of smoking on the onset of cardiovascular diseases.

Moreover, we showed that smoking initiation in adolescence and in early adulthood both significantly elevate the risks of cardiovascular and mortality compared to starting smoking at age 30 or above. While age category definitions have been inconsistent across other studies, significant increase in cardiovascular risk from early age at initiation were only demonstrated in adolescent-onset smokers below the ages of 1220, 1315, 1514,19, or 1822 relative to adult-onset smokers. Our results suggest that the cardiovascular effects of earlier smoking initiation extend into young adulthood, albeit to a lesser extent than those of adolescent smoking. As there has been a recent shift of age at smoking initiation to early adulthood35, these findings provide additional evidence in support of smoking prevention measures targeted toward young adults.

Psychosocial factors provide a potential biological explanation for the negative cardiovascular effects of early smoking initiation specific to adolescents and young adults. Psychosocial risk factors such as parental and peer smoking, school factors, and stress have been associated with adolescent smoking behavior36. Psychological stress by itself promotes cardiovascular disease through inflammation37. Adolescents exposed to parental and peer smoking are also more likely to have chronic exposure from secondhand smoke, which may have 80 to 90% of cardiovascular risk conferred by active smoking11. Furthermore, these psychosocial factors often do not resolve in early adulthood as many continue schooling in college. Since most smokers in our cohort were male, they were also subject to conscription in Korea, where mandatory military service has been shown to promote smoking38,39. Overall, these life stage-specific psychosocial factors could have exerted significant effects on cardiovascular risks in both adolescence and early adulthood, although we were unable to assess these factors in this study.

Another major explanation for the cardiovascular consequences of early smoking initiation has been its associations with traditional atherosclerotic risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity15,40,41,42. These associations have been linked to lifestyle differences that may persist even after smoking cessation15, and adolescent physical activity was noted to be the strongest lifestyle parameter related to coronary heart disease43. Some studies associating age at smoking initiation with cardiovascular risks were not able to adjust for lifestyle factors14,19,44, which could lead to an overestimation of the risks. However, other studies reported elevated cardiovascular risks even after adjusting for physical inactivity and obesity15,22. As our analysis also adjusted for major behavioral factors and socioeconomic status, the current findings more strongly suggest that the cardiovascular risks from early initiation of smoking is more than a mere reflection of an individual sedentary lifestyle.

Additional behavioral risk factors associated with early smoking initiation, as potential confounders, may also contribute to the observed increase in cardiovascular risks. Smoking initiation at a young age has been frequently associated with high-risk behaviors including alcohol consumption45,46,47. In addition, smokers are more likely to consume ultra-processed meals even after adjustment for socioeconomic status and body mass index48, and a survey-based study in Korea also found that adolescent smokers consumed more fast food than their nonsmoker counterparts49. Since alcohol intake and processed food consumption are well-established risk factors that can lead to the development of cardiovascular disease independent of smoking6,50, they are important confounders that must be considered in our analysis. We were not able to adjust for dietary patterns, and while we have adjusted for self-reported alcohol consumption, this one-time record does not necessarily reflect longitudinal drinking behavior and may leave residual confounding. At the same time, we note that unhealthy lifestyle in young smokers may also be acting as an effect mediator. Since nicotine affects cognition, emotion, and motivation in the brain18, these observed associations with unhealthy behaviors in early-onset smokers may also be partly explained by the biological effects of cigarette smoking at young ages. As such, behavioral risk factors of cardiovascular disease are important confounders as well as possible effect mediators that must be considered in interpreting the elevated risks of cardiovascular diseases among early-onset smokers.

Our study has several limitations. Since smoking status was determined based on a one-time questionnaire, there may be significant recall bias and underreporting as well as changes in smoking intensity over time that are not reflected in our estimation of total PY. Designation as a former smoker was based on self-reporting, and data on years since quitting smoking were unavailable, so we could not confidently distinguish current and former smokers in our analysis. Our operational definition of MI and stroke occurrence could also have been subject to misclassification. While a nine-year follow-up revealed significant differences in risks of incident cardiovascular disease, it may not have been sufficient to evaluate mortality, especially in younger individuals. Indeed, relative risk differences in all-cause death were unclear in early-onset smokers, while they were evident for those with age at initiation ≥ 30. The low unadjusted risk relative to nonsmokers in early-onset smokers suggests that the significant increases in cardiovascular morbidity do not translate into mortality in these young smokers over nine years of follow-up. Moreover, there may be additional confounding factors that are not assessed given the retrospective nature of the study, particularly due to the differences in baseline ages that predispose our results to birth cohort effects. While we have discussed major confounding factors with known associations to both cardiovascular disease and early age at smoking initiation, there are additional major cardiovascular risk factors that were not considered in our analysis. Family history of premature cardiovascular disease is a key risk factor that can nearly double the risk of cardiovascular events6,51, but we were unable to adjust for this information or other genetic determinants of cardiovascular risk in our multivariate model. Other significant cardiovascular risk factors such as air pollution and additional comorbid conditions not included in our analysis should also be acknowledged as possible confounders. The smokers in the cohort were also predominantly male, although we performed subgroup analyses for females and found consistent results. Finally, our findings may have limited generalizability to non-Asians.

In conclusion, early smoking initiation as adolescents or young adults was associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Earlier initiation of smoking also significantly accentuated the increases in cardiovascular risks from greater total pack-years of smoking. Our results highlight the need for smoking prevention efforts directed toward adolescents and young adults to improve cardiovascular health at the population level, and further studies will be necessary to delineate the roles of biological and psychosocial factors at play.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea (NHIS), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from either co-corresponding author (Kyungdo Han or Sehoon Park) upon reasonable request and with permission from the NHIS, which can be requested through the National Health Insurance Data Sharing Service website at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr.

References

United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of smoking–50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 2014).

Collaborators, G. B. D. R. F. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2162–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00933-4 (2024).

He, H. et al. Health effects of Tobacco at the Global, Regional, and national levels: results from the 2019 global burden of Disease Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 24, 864–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab265 (2022).

Cheon, E. et al. Smoking-attributable mortality in Korea, 2020: a Meta-analysis of 4 databases. J. Prev. Med. Public. Health. 57, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.23.471 (2024).

Messner, B. & Bernhard, D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 34, 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.300156 (2014).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 147, e93–e621. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123 (2023).

Chang, C. M., Corey, C. G., Rostron, B. L. & Apelberg, B. J. Systematic review of cigar smoking and all cause and smoking related mortality. BMC Public. Health. 15, 390. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1617-5 (2015).

Burns, D. M. Epidemiology of smoking-induced cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 46, 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-0620(03)00079-3 (2003).

Lee, P. N. Tar level of cigarettes smoked and risk of smoking-related diseases. Inhal Toxicol. 30, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958378.2018.1443174 (2018).

Hackshaw, A., Morris, J. K., Boniface, S., Tang, J. L. & Milenkovic, D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 360, j5855. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5855 (2018).

Barnoya, J. & Glantz, S. A. Cardiovascular effects of secondhand smoke: nearly as large as smoking. Circulation 111, 2684–2698. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492215 (2005).

Pleasants, R. A., Rivera, M. P., Tilley, S. L. & Bhatt, S. P. Both duration and pack-years of Tobacco Smoking should be used for clinical practice and research. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 17, 804–806. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202002-133VP (2020).

Lubin, J. H. & Caporaso, N. E. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer: modeling total exposure and intensity. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0863 (2006).

Thomson, B. et al. Childhood Smoking, Adult Cessation, and Cardiovascular Mortality: prospective study of 390 000 US adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e018431. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018431 (2020).

Choi, S. H. & Stommel, M. Impact of age at smoking initiation on smoking-related morbidity and all-cause mortality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 53, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.009 (2017).

Nash, S. H., Liao, L. M., Harris, T. B. & Freedman, N. D. Cigarette smoking and mortality in adults aged 70 years and older: results from the NIH-AARP Cohort. Am. J. Prev. Med. 52, 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.036 (2017).

Raghuveer, G. et al. Cardiovascular consequences of Childhood Secondhand Tobacco smoke exposure: prevailing evidence, Burden, and racial and socioeconomic disparities: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 134, e336–e359. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000443 (2016).

Yuan, M., Cross, S. J., Loughlin, S. E. & Leslie, F. M. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J. Physiol. 593, 3397–3412. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP270492 (2015).

Thomson, B. et al. Association of childhood smoking and adult mortality: prospective study of 120 000 Cuban adults. Lancet Glob Health. 8, e850–e857. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30221-7 (2020).

Fa-Binefa, M. et al. Early smoking-onset age and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. Prev. Med. 124, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.022 (2019).

Kim, C. Y. et al. The Association of Smoking Status and Clustering of Obesity and depression on the risk of early-onset Cardiovascular Disease in Young adults: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Korean Circ. J. 53, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2022.0179 (2023).

Huxley, R. R. et al. Impact of age at smoking initiation, dosage, and time since quitting on cardiovascular disease in African americans and whites: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 175, 816–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr391 (2012).

Kenfield, S. A., Stampfer, M. J., Rosner, B. A. & Colditz, G. A. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA 299, 2037–2047. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.17.2037 (2008).

Nance, R. et al. Smoking intensity (pack/day) is a better measure than pack-years or smoking status for modeling cardiovascular disease outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 81, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.010 (2017).

Liang, T. et al. Age at smoking initiation and smoking cessation influence the incidence of stroke in China: a 10-year follow-up study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 56, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-023-02812-y (2023).

Rissanen, I., Oura, P., Paananen, M., Miettunen, J. & Geerlings, M. I. Smoking trajectories and risk of stroke until age of 50 years - the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. PLoS One. 14, e0225909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225909 (2019).

Kim, M. K., Han, K. & Lee, S. H. Current trends of Big Data Research Using the Korean National Health Information Database. Diabetes Metab. J. 46, 552–563. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0193 (2022).

Jeong, H. G. et al. Physical activity frequency and the risk of stroke: a Nationwide Cohort Study in Korea. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6 https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005671 (2017).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644 (2009).

Leffondre, K., Abrahamowicz, M., Siemiatycki, J. & Rachet, B. Modeling smoking history: a comparison of different approaches. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156, 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf122 (2002).

Makover, M. E., Shapiro, M. D. & Toth, P. P. There is urgent need to treat atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk earlier, more intensively, and with greater precision: a review of current practice and recommendations for improved effectiveness. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 12, 100371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100371 (2022).

Shrestha, R. & Copenhaver, M. Long-Term effects of Childhood Risk factors on Cardiovascular Health during Adulthood. Clin. Med. Rev. Vasc Health. 7, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4137/CMRVH.S29964 (2015).

Raitakari, O. T. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young finns Study. JAMA 290, 2277–2283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.17.2277 (2003).

Jacobs, D. R. Jr. et al. Childhood Cardiovascular Risk factors and Adult Cardiovascular events. N Engl. J. Med. 386, 1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109191 (2022).

Barrington-Trimis, J. L. et al. Trends in the age of cigarette smoking initiation among young adults in the US from 2002 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2019022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19022 (2020).

Tyas, S. L. & Pederson, L. L. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tob. Control. 7, 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.7.4.409 (1998).

Wirtz, P. H. & von Kanel, R. Psychological stress, inflammation, and Coronary Heart Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 19, 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0919-x (2017).

Allem, J. P., Ayers, J. W., Irvin, V. L., Hofstetter, C. R. & Hovell, M. F. South Korean military service promotes smoking: a quasi-experimental design. Yonsei Med. J. 53, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2012.53.2.433 (2012).

Bethmann, D. & Cho, J. I. Conscription hurts: the effects of military service on physical health, drinking, and smoking. SSM Popul. Health. 22, 101391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101391 (2023).

Flouris, A. D., Faught, B. E. & Klentrou, P. Cardiovascular disease risk in adolescent smokers: evidence of a ‘smoker lifestyle’. J. Child. Health Care. 12, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493508092509 (2008).

Twisk, J. W., Van Mechelen, W., Kemper, H. C. & Post, G. B. The relation between long-term exposure to lifestyle during youth and young adulthood and risk factors for cardiovascular disease at adult age. J. Adolesc. Health. 20, 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00183-8 (1997).

Choi, S. H., Stommel, M., Broman, C. & Raheb-Rauckis, C. Age of smoking initiation in relation to multiple health risk factors among US adult smokers: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Data (2006–2018). Behav. Med. 49, 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2022.2060930 (2023).

Twisk, J. W., Kemper, H. C., van Mechelen, W. & Post, G. B. Which lifestyle parameters discriminate high- from low-risk participants for coronary heart disease risk factors. Longitudinal analysis covering adolescence and young adulthood. J. Cardiovasc. Risk. 4, 393–400 (1997).

Honjo, K. et al. The effects of smoking and smoking cessation on mortality from cardiovascular disease among Japanese: pooled analysis of three large-scale cohort studies in Japan. Tob. Control. 19, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2009.029751 (2010).

Hanna, E. Z., Yi, H. Y., Dufour, M. C. & Whitmore, C. C. The relationship of early-onset regular smoking to alcohol use, depression, illicit drug use, and other risky behaviors during early adolescence: results from the youth supplement to the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Subst. Abuse. 13, 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00077-3 (2001).

Altwicker-Hamori, S. et al. Risk factors for smoking in adolescence: evidence from a cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18695-4 (2024).

O’Loughlin, J., Paradis, G., Renaud, L. & Sanchez Gomez, L. One-year predictors of smoking initiation and of continued smoking among elementary schoolchildren in multiethnic, low-income, inner-city neighbourhoods. Tob. Control. 7, 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.7.3.268 (1998).

Lin, W. et al. Dietary patterns among smokers and non-smokers: findings from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES). Nutrients 16, 2017–2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132035 (2024).

Lee, B. & Yi, Y. Smoking, physical activity, and eating habits among adolescents. West. J. Nurs. Res. 38, 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914544335 (2016).

Lichtenstein, A. H. et al. Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 144, e472-e487, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001031 (2021).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Parental cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged adults: a prospective study of parents and offspring. JAMA 291, 2204–2211. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.18.2204 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHK, KH, SJ, SL, YK, SGK, DKK, and SP contributed to the study conception and design. KH performed data curation and provided methodology. JHK, KH, MK, JMC, SL, YK, SC, HH, EK, KWJ, DKK, and SP provided statistical expertise and interpreted the data. KH, DKK, and SP supervised the overall project. JHK, KH, and SP prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors participated in subsequent revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by a fund from Seoul National University (800-20190571).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koh, J.H., Han, K., Kim, M. et al. Early age at smoking initiation is associated with elevated cardiovascular disease and mortality risk in a nationwide population-based cohort. Sci Rep 16, 3063 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88253-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88253-4