Abstract

Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are widely used in biomechanical data analysis but have the significant limitations in interpretability and decision transparency. Combining graph neural networks (GNN) with gate recurrent units (GRU) may offer a better solution. This study proposes and validates a hybrid GNN-GRU model for predicting baseball pitching speed and enhancing its interpretability using layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP). C3D data from 53 baseball athletes were downloaded from a public dataset. Kinematic features of 9 joints and pitching speed during the pitching process were calculated using Visual3D, resulting in a total of 208 valid pitches. The feature data were input into both LSTM and GNN-GRU hybrid models, with hyperparameters tuned using particle swarm optimization. LRP was employed to obtain the contribution rate changes of kinematic features to the prediction results throughout the pitching cycle. The prediction accuracy of the models was evaluated using mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and R-squared (R2). The results showed that there were the significant statistical differences in the MAE and R2 metrics between the LSTM model and the GNN-GRU model in predicting pitching speed on the test set. The MAE (P = 0.000, Z = − 5.170, Cohen’s d = 1.514) and R2 (P = 0.000, Z = − 2.981, Cohen’s d = 2.314) of the LSTM model were significantly lower than those of the GNN-GRU model. Compared to LSTM, the GNN-GRU model achieved better prediction accuracy but was potentially more susceptible to the influence of data variability. Moreover, the GNN-GRU-based model demonstrated the better interpretability and decision transparency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of biomechanics, several models have emerged for predicting continuous time variables, including convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Among these, LSTM networks are the most widely used1. Studies have used LSTM models to predict joint torques, ground reaction forces during running, and the center of pressure during gait in real time using video or inertial sensor data2,3,4.

Theoretically, when graph neural networks (GNN) are combined with gate recurrent units (GRU), the GNN captures the feature relationships between nodes5, while the GRU captures the temporal dependencies of these features. Recent studies have reported the GNN-GRU models used for spatiotemporal traffic flow prediction6. Traffic flow dynamics change over time (e.g., during rush hours) and are influenced by the flow on adjacent roads or intersections. This is similar to human movement, where the motion of one joint depends not only on its temporal sequence but also on the coordinated movement of other joints. During human movement, each joint can be considered as a node and each bone as an edge, with each node possessing its own characteristics, such as joint angles, angular velocities, and torques. This can naturally be understood as a sparse directed graph structure. Unlike LSTM with a three-gate structure, a GRU consists of a two-gate structure with an update gate and a reset gate. Secondly, the GRU does not use a separate memory cell to store information but directly utilizes hidden units to record historical states. The reset gate controls the amount of current and memory information, generating the new memory information to be propagated forward. Finally, the GRU eliminates the linear self-update of memory cells, instead performing linear updates directly within hidden units using gates. These features result in a simpler structure for the GRU with the lower computational costs and model complexity. In some tasks, the GRU has outperformed traditional LSTM models7.

Recent studies have begun exploring the application of GNN models in biomechanics; however, they invariably overlook the interpretability of the models8,9. Achieving high-accuracy prediction and classification of target variables is not the ultimate goal of neural network models; the rationale for exploring a novel model in biomechanics must be more compelling. Specifically, interpretability means that neural network models should provide decision-making information for the prediction or classification process. However, all neural network models face black box problems. Due to the nonlinearity and complexity of mappings between different layers of the network, neural network models cannot offer any insight into the decision-making process. This lack of transparency prevents researchers from verifying the reasonableness of the model’s decisions. Recently, several algorithms have been developed to enhance the interpretability of neural network models. For example, layerwise relevance propagation (LRP) can output the contribution rate of each input variable to the prediction result and allow researchers to verify whether the model’s prediction or classification results are realistic. LRP technology has already been applied in biomechanics, providing transparent decision-making information for the prediction of personalized gait features or the assessment of injury risk upon landing10,11, thereby increasing the interpretability of the results. This helps researchers propose more valuable biomechanical diagnoses and analyses. However, traditional LSTM models include three gates (input, forget, and output gates) and an additional cell state due to their complexity, and suffer from exponential decay of relevance across layers, making only the relevance results from the most recent few time steps reliable. The GNN-GRU model does not have this issue, because GRU has a simpler architecture with only two gates (update and reset gates)12. Recent studies have used GNN and LRP to quantify the interactions between proteins and ligands in a given complex13, and the standard LRP rules have been employed without involving complex LRP variants.

In this study, we modeled the pitching speed of 53 baseball athletes using both LSTM and GNN-GRU models. We analyzed the reliability of the GNN-GRU model in handling time-series data and used the LRP to validate the influence of each feature on the dependent variable during pitching to enhance the model interpretability. The motivation for selecting this project stems from the fact that numerous studies have examined the relationship between independent variables and pitching speed14,15,16,17; however, these studies primarily focus on discrete variables, such as the mean or maximum values of features, and their association with pitching speed. While a few studies have utilized the advanced methods, such as principal component analysis (PCA), to analyze pitching from a time-series perspective, but they barely have quantified the contribution of each variable to pitching velocity at each specific time point18,19. Given that successful pitching relies on dynamic energy transfer within the kinetic chain, understanding this issue is crucial. Additionally, in this study, we used the LRP to determine the influence of independent variables on pitching speed, and it was needed to verify that the relevance of the results output by the LRP were consistent with physiological and physical principles. We hypothesized that (1) the GNN-GRU model achieved the prediction accuracy comparable to that of LSTM, and (2) the GNN-GRU model successfully applied the LRP, and output the reliable relevance results between the independent and dependent variables.

Results

Kinematic features of baseball pitching

In the early phase of pitching, the trunk leaned forward, while the right hip and knee joints flexed to allow sufficient joint mobility for extension and push-off. Subsequently, the hip and knee joints extended, and the ankle plantarly flexed to generate force for propelling the body toward the mound. The left ankle underwent plantar flexion, and the left knee and hip extended to take a step forward. Both shoulder joints continuously rotated internally. After the foot contact, the left ankle continued to plantarly flex, the left knee transitioned from flexion to extension, and both hip joints continued to flex in coordination with the forward-leaning trunk, reaching their peak at the moment of maximum external rotation (MAX ER). The right shoulder continued to rotate externally, reaching its peak at MAX ER before rapidly rotating internally to release the ball (Fig. 1).

Changes of the kinematic features throughout the pitching cycle. Units are the degrees (°). The black vertical line represents the time point of the stride limb contact with the mound, and the green vertical dash dot line represents the time point when the throwing arm shoulder joint reaches maximum external rotation. Abbreviation: EXT extension, FLE flexion, PF plantar flexion, DF dorsiflexion, ER external rotation, IR internal rotation.

Performance of the LSTM and GNN-GRU models

The MAE and R2 values did not conform to a normal distribution, so nonparametric tests were used. The results showed that there were the significant differences in the MAE and R2 between the LSTM model and the GNN-GRU model in predicting pitching speed on the test set. The MAE (P = 0.000, Z = − 5.170, Cohen’s d = 1.514) and R2 (P = 0.000, Z = − 2.981, Cohen’s d = 2.314) of the LSTM model were significantly lower than those of the GNN-GRU model (Table 1).

Statistical analysis was performed on the R2 and MAE of the prediction results for the nine kinematic features, similar to the statistical results for pitching speed. The LSTM model exhibited the lower MAEs, but the R2 values were also significantly lower than those of the GNN-GRU model (Table 2).

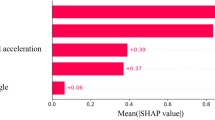

Layer wise relevance propagation outputs

The contribution rate variations of the nine features throughout the pitching cycle were determined by the LRP (Fig. 2). The contribution rates ranged from 0 to 1, where 0 indicated no influence on the dependent variable (pitching speed) and 1 represented the maximum influence. The roles of all the features during pitching were broadly categorized into two types: (1) features with decreasing contribution rates as the pitching phase progressed, including the left ankle, left knee, right ankle, right knee, and right hip; (2) features with increasing contribution rates as the pitching phase progressed, including the left hip, left shoulder, right shoulder, and trunk.

Contribution rate variations of the nine features throughout the pitching cycle as determined by the LRP. The contribution rates have been normalized to a range of 0–1. The black vertical line represents the time point of the trailing limb contact with the force platform, and the green vertical dash-dot line represents the time point when the throwing arm shoulder joint reaches maximum external rotation.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed a GNN-GRU hybrid model based on LRP to predict baseball pitching speed and compared it with the traditional LSTM model. The results showed that the GNN-GRU model successfully output the contribution rate changes of nine kinematic features to the predicted pitching speed throughout the entire pitching cycle. Furthermore, whether predicting pitching speed or kinematic features, the MAE and R2 of the LSTM model were the significantly lower than those of the GNN-GRU model.

LSTM networks have been successfully used to predict various biomechanical variables, such as ground reaction forces during gait in stroke patients, lower limb kinematics during gait, and upper limb joint dynamics during daily activities4,20,21. In this study, the LSTM model and the GNN-GRU model worked under two conditions: (1) predicting pitching speed based on the relationship between nine kinematic features and pitching speed, and (2) directly predicting the changes in kinematic features throughout the pitching cycle. The GNN-GRU achieved a higher R2, indicating that the GNN-GRU captured the complex structures within the data. This may be attributed to the ability of the GNN-GRU model to model the human body as a graph structure, viewing joints as nodes and thereby learning the intricate relationships between joints to achieve better predictions. However, the MAE of the GNN-GRU model was significantly higher than that of the LSTM model, suggesting that the GNN-GRU model may be more sensitive to the variability of the data. This variability likely reflects the differences in locomotion patterns among the athletes. The GNN-GRU model also has another advantage. Neural network models can easily find arbitrary functions to fit the relationships between dependent and independent variables through the nonlinearity of multilayer networks. However, the direct structure of the fitted model cannot provide the insights into the relative importance, fundamental relationships, structure, or covariates of the prediction variables22. The opaque decision-making process leads researchers to question the validity of the output results. Although researchers have developed the methods to improve decision transparency, the unique structure of LSTM inherently limits its interpretability. Firstly, LSTM models include not only linear mappings but also multiplicative interactions, which complicate the calculation of relevance scores when linear or nonlinear mappings and multiplicative interactions are mixed, often requiring special relevance allocation principles, such as “signal-taking-all”23. Secondly, the information in the state unit accumulates and updates over time steps through the forget gate, meaning that relevance scores from early time steps decay exponentially during backpropagation24, preventing access to relevance data across the entire action cycle. These issues necessitate the use of special variants of interpretability techniques in LSTM, increasing model deployment and computational costs. Applying the LRP is less complex with the GNN-GRU model. In this study, we used the most basic form of the LRP to quantify the correlations between the nine kinematic features and the predicted pitching speed, which was discussed further below.

Transparency in the decision-making process of neural network models is crucial in biomechanics. Understanding how independent variables influence prediction outcomes helps improve sport techniques or prevent injuries. For example, the LRP can reveal the differences in kinematic features between expert and novice runners or identify high-risk landing patterns10,11. In this study, the LRP results provided the deep insights into the relationship between kinematic features and pitching speed. The results showed that the contribution rates of the right ankle, right knee, right hip, and left knee joints were high in the early stages and decreased significantly after the stride limb contact, while the contribution rate of the left hip joint was low in the early stages but increased rapidly before and after stride limb contact. Previous studies have shown that the trailing limb is crucial in the early and mid-phases of pitching25, generating energy to propel the body toward the mound. The energy from the ankle joint of the trailing limb increases after the start of the action, peaking shortly before stride foot contact, with the energy from the hip joint peaking slightly later, both decreasing to the low levels before ball release. This finding aligns with our LRP results, where the contribution rates of these joints peak at the stride foot contact and then decline before the throw. Greater extension of the trailing limb increases stride length26, delays stride foot contact, and allows more time to transfer linear momentum from the trailing limb to the trunk and throwing arm, increasing ball speed in the later stages of the pitching27. Additionally, greater stride knee extension is beneficial for leg stability, a key characteristic of high-speed pitchers, while low-speed pitchers typically exhibit greater knee flexion (less extension). Since the ground reaction force (GRF) at the stride foot contact is a crucial source of energy for the trunk and throwing arm28, the differences in the kinematics of the stride knee joint may affect the length of muscle-tendon units, such as the soleus, impacting GRF absorption at the stride foot contact17 and thus the efficiency of energy transfer through the kinetic chain16,29. The changes in the contribution rates of these joints to pitching speed and their feature trends suggest that before stride limb contact, the right ankle should have greater plantar flexion, and the right hip and both knees should extend more. After stride limb contact, the left hip should flex more, as greater hip flexion is typically associated with a longer stride length. A greater stride length can enhance an athlete’s ability to generate forward momentum. These findings suggest that athletes should focus on improving their lower limb joint range of motion (ROM) and incorporating training that targets the entire lower limb kinetic chain to enhance inter-joint coordination. Previous studies have confirmed that both ROM and coordination abilities play a critical role in achieving high-speed pitching18,30,31. The trunk’s contribution rate increases rapidly after stride limb contact. The trunk’s kinematics affect the ball’s movement distance before the release. After the stride limb contacts the ground, the trunk begins to extend, reaches its peak quickly, then flexes again, and leans forward to throw the ball. The LRP results suggest that greater extension is necessary because it allows for a greater range of flexion. Greater forward tilt of the trunk leads the throwing arm, requiring the humerus to overcome a greater horizontal abduction angle to release the ball, extending the time for the humerus to reach maximum horizontal abduction, and providing more time to accelerate the angular velocity of the throwing arm, thereby increasing ball speed32. Each additional 10° of trunk forward tilt increases elbow varus torque by 3.3%, further increasing ball speed33. Meanwhile, increased trunk forward flexion creates additional space and time for the rotation of the pelvis, sacral vertebrae, lumbar vertebrae, and thoracic vertebrae. Previous studies have confirmed that a trunk forward flexion angle of 45° generates an additional 19° of rotational space. This additional rotation plays a crucial role in enhancing ball velocity34,35. Furthermore, the contribution rate of the right shoulder joint increases rapidly after stride limb contact and continues to increase until the end of the throw. This trend suggested that the right shoulder joint should be externally rotated as much as possible. Greater external rotation means that if the athlete maintains the same timing for ball release, a faster internal rotation angular velocity is needed to release the ball. Faster humeral internal rotation angular velocity is a key feature distinguishing fastballs from slower pitches36. Undoubtedly, the LRP results easily show the impact of each feature on the prediction outcome, enhancing the transparency of the model’s decision-making process.

Another advantage of the GNN-GRU is its potential to quantify motor coordination and control. The GNN can capture information about a node and its neighboring nodes, the capability that LSTM, RNN, and CNN models lack since they only consider the temporal relationships of features without considering the spatial correlations between the features. Yao et al. achieves a robot arm optimal torque distribution at each joint during tasks using the GNN model37. From this perspective, GNN has exciting potential for human motor control and may replace analytical methods in motor control fields, such as uncontrolled manifolds, continuous relative phases, or nonnegative matrix factorization. EMG signals are processed on an edge computing platform at very high speeds, and the coordination relationships between muscles in a graph structure are captured, enhancing the speed and accuracy of prosthesis control. Future research should explore the application prospects of GNN in the field of motor control.

This study utilized a publicly available dataset, and due to privacy policies, we could not fully access all information related to data collection, particularly the skill level, age, and injury status of each subject. We failed to ensure if these factors contaminated the dataset and consequently affected the model’s results. However, this study is methodological in nature and has demonstrated the accuracy of the GNN-GRU model in predicting continuous data and the transparency of its decision-making process. Therefore, even if the dataset is contaminated, it should not impact the findings of this study. Moreover, we did not include rotational kinematic features around the vertical axis in this study. According to the previous research findings38, the athletes exhibited substantial variability in rotational styles, leading to the significant individual differences. Ignoring such variability when training and predicting with the model might negatively impact its performance. In future studies, researchers utilize the GNN-GRU model to explore these rotational kinematic features deeply, potentially enhancing our understanding of their roles in pitching biomechanics and improving the model accuracy.

Conclusion

This study examined the application of a novel model in biomechanical data analysis. Compared to traditional LSTM, the GNN-GRU model achieved better prediction accuracy but was potentially more susceptible to the influence of data variability. Moreover, the GNN-GRU-based model demonstrated the better interpretability and decision transparency.

Methods

This study presented a secondary analysis of data from the Open Biomechanics Project, including an anonymous dataset of elite athlete motion capture data. The dataset was developed and maintained by Wasserberger et al.39. The details of the data collection process were described below.

Open biomechanics project dataset

Participants

The dataset includes motion capture data of 100 baseball athletes during pitching [age: 21 (2) years, height: 1.85 (0.07) m, weight: 90.7 (10.2) kg]. Ethical approval for all data collection procedures was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (Western IRB # WB-DLR-115).

Experimental protocol

Each athlete had 39 markers attached to their body and used a standard baseball weighing 140 g for pitching. Three-dimensional ground reaction force data were collected using three force plates arranged in a T-configuration in the center of the field (sampling rate: 1080 Hz, model: 6090-06 and 9090-15, Betrec Inc., Italy) and covered with 0.5-inch-thick turf. A 15-camera motion capture system (sampling rate: 360 Hz, model: Optitrack Prime 17 W, Natural Point Inc., Canada) was used to capture the trajectories of the markers (Fig. 3A,B). The global coordinate system was defined as follows (Fig. 3C): the X-axis was in the anterior-posterior direction (positive toward the home plate), the Y-axis was in the lateral direction (positive toward the first base), and the Z-axis was in the vertical direction (positive upward). Each subject performed at least three valid fast balls, with some performing up to five. The data from these valid pitches were saved as C3D files along with each subject’s static calibration file.

Data analysis

Considering the biomechanical differences between left-handed and right-handed pitchers40, we excluded left-handed pitchers and downloaded the data from 53 [height: 1.82 (0.07) m, weight: 89.8 (9.8) kg] right-handed pitchers (see Appendix). Using the static files for each subject, we created a body model in Visual 3D (version: V6 Professional, Has-Motion, Kingston, Canada). Following previous studies41, we defined the start of the pitching as the time point when the stride limb hip flexion angle reached its maximum and the end of the pitching as the time point when the release occurred (Fig. 4). The time between these two points was defined as the pitching phase. Joint angles in the sagittal plane for the bilateral ankles, knees, hips, trunk, and shoulders were calculated using the XYZ Cardan sequence (Table 3).

Since the dataset did not provide continuous ball speed data, we calculated the resultant speed of the throwing hand in three-dimensional space as the dependent variable42. The joint angle and throwing speed data were filtered using a 4th-order low-pass filter at 6 Hz. All joint angles and pitching speeds during the pitching phase were exported as ASCII txt files and subsequently interpolated to a length of 101 to represent 0–100% of the pitching phase. The data were then standardized using Z score normalization and converted to CSV files, resulting in a 9 × 101 matrix for the features and a 1 × 101 matrix for pitching speed. A total of 208 valid pitchings were exported and saved.

Deep learning

Long short-term memory model

In this study, we constructed a basic LSTM neural network model with several hidden layers and one fully connected layer (see “Particle swarm optimization” section). The number of neurons in each hidden layer and the learning rate were determined using an optimization algorithm (see the “Particle swarm optimization” section). Each hidden layer was followed by a 20% dropout to reduce the risk of overfitting1,43. The LSTM model accepted a 9 × 101 feature matrix as input, with each column representing a feature (joint angle) and each row representing the value of that feature at each time point during the pitching cycle. When the model was used to predict pitching speed, the output dimension of the fully connected layer was 1, and the pitching speed CSV file was used as the target variable, which was compared with the model’s output to guide the hyperparameter updates. When the model was used to predict kinematic features, the output dimension of the fully connected layer was 9, and the pitching speed of the CSV file did not play a role.

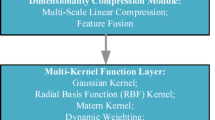

Graph neural networks and gate recurrent units

In this study, we used a hybrid model of a GNN and a GRU consisting of several hidden layers (see the “Particle swarm optimization” section), one GRU layer, and one fully connected layer (Fig. 5). GNNs are characterized by edge features and node indices, which need to be provided during model training. The pitching data for each pitching were a 9 × 101 matrix, where 9 represented the features (joint angles) and 101 represented 0–100% of the action cycle. This matrix was converted into graph data, with each column representing a node and each row representing the value of that feature at the current time point. The edge feature matrix did not assign additional features to the edges, resulting in an all-ones matrix. For the node index matrix, based on uncontrolled manifold theory, it is established that to achieve optimal movement performance, there are complex coordination effects among joints, even between distant joints44,45. Therefore, each node was connected by an edge to form a complete graph rather than connecting only adjacent joints.

GNN-GRU model architecture. (A) The implementation principle of the GNN, where ni represents nodes (joints), ej, sj, rj represent the set of edge features (bones), \(e_{j}\) represents the edge features, and sj, rj represent the start and end nodes of an edge, respectively. g denotes the global features of the graph. \(f_{g}\), fn, fe represent the global update function, node update function, and edge update function, respectively. GN1, GN2, and GN3 represent the three convolutional layers, GRU represents the gated recurrent unit layer, and Linear represents the fully connected layer. (B) The hybrid model used in this study, where Node features represent the feature matrix, Target variables represent the pitching speed matrix, and Edge index represents the edge index matrix. (C) Architecture of gated recurrent unit.

During model training, these matrices were first passed to the convolutional layers, which aggregated the features of a node and its neighboring nodes to capture potential relationships between different nodes and between features and the dependent variable. Each convolutional layer was followed by a ReLU activation function to introduce nonlinearity. The number of convolutional layers, learning rate, and number of neurons per layer were determined by optimization (e.g., Particle swarm optimization). Next, a GRU layer was used to capture temporal dependencies in the sequential data, followed by a fully connected layer to output the results (Fig. 5). As described earlier with the LSTM, the output dimension of the fully connected layer varied depending on whether the pitching speed or kinematic features were being predicted. This process was implemented using Python with PyTorch and torch geometric libraries.

Particle swarm optimization

Particle swarm optimization (PSO) was employed to automatically find the optimal hyperparameters for the neural network models46. For both models, the range for the number of nodes per convolutional layer was set between 2 and 256, the number of layers was set between 2 and 3, and the learning rate was set between 0.001 and 0.1. Each combination of hyperparameters was run for 100 epochs during the iterations, and the combination with the lowest loss was considered the optimal set and subsequently validated on the test set. The implementation process is as follows:

where \(w\) is the inertia weight controlling the influence of the particle’s previous velocity on its current velocity; \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\) are acceleration coefficients representing the weight of the particle’s movement toward its personal best position and the global best position, respectively; and \({r}_{1}\) and \({r}_{2}\) are random numbers between [0,1] to introduce randomness.

The current position of particle \({x}_{i}\left(t+1\right)\) is updated by adding the new velocity \({v}_{i}(t+1)\), ensuring that the particle moves within the search space.

where \(f\) is the objective function to be minimized. After updating the position, each particle updates its historical best position if the current position’s objective function value is better than its historical best.

Among the historical best positions of all the particles, the one with the minimum objective function value was selected as the global best position. To ensure the model’s generalizability, a cross-validation algorithm was used. The entire dataset was split into an 80% training set, a 10% test set, and a 10% validation set. The training set was used to learn the features, and the PSO algorithm was run on the validation set to adjust the hyperparameters. Finally, the model performance and results were evaluated on the test set, which contained data never used in training and validation. A total of 53 subjects performed 208 pitchings, resulting in 208 samples, with 166 samples in the training set and 21 samples each in the test and validation sets. This process was implemented using custom Python code with the pyswarm and KFold libraries.

Layer wise relevance propagation

LRP was employed to calculate the relevance of each feature to the dependent variable, thereby enhancing model interpretability. Specifically, when we used the model to predict the pitching speed, we used the LRP method to compute the contribution rate of each feature to the prediction. Assuming that the model’s predicted value is \(\widehat{y}\) and that the input features are \(x\), the process of the LRP is as follows:

The input features are forward propagated through the GNN model to obtain the predicted value \(\widehat{y}\). The gradient of the predicted value is then backpropagated to the input features using the chain rule. To achieve this, the LRP scores through each layer of the network. The process involves two main steps: the output \({f}_{(x)}\) is taken as the initial relevance score \({R}_{i}\), and this relevance is then backpropagated from the output layer to the input layer. The propagation rule for each layer is defined as:

where \({R}_{j}\) represents the relevance score of the j-th node in the current layer, \({R}_{i}\) represents the relevance score of the i-th node in the previous layer, \({x}_{j}\) denotes the input activation value of the j-th node in the current layer, \({w}_{ij}\) is the weight from the j-th node in the current layer to the i-th node in the previous layer, and \({\sum}_{k}{x}_{k}{w}_{ik}\) is the weighted sum of activation values and connection weights for all nodes in the current layer. When handling continuous numerical variables, this calculation is performed at each time point, resulting in a temporal profile of relevance scores over the entire action cycle. Overall, the LRP decomposes the model’s prediction into contributions from individual input features via layerwise propagation of relevance scores. This process was implemented using custom Python code with the investigated library.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the model, we calculated the mean absolute error (MAE) and R-squared (R2) between the predicted and actual pitching speeds, as well as the actual and predicted results of the nine kinematic features for each sample in the test set47. These metrics provided a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 26.0, IBM, Inc., Newark, USA). The normality of the distributions of the MAEs and R2 outputs for the two models on the test set was assessed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. If the data followed a normal distribution, an independent sample t test was used to examine the differences in prediction accuracy between the two models. If the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann‒Whitney U test was applied. The effect sizes were reported using Cohen’s d, with the following interpretation standards: = 0.8 (large), = 0.5 (medium), = 0.2 (small)48. The significance level for the study was set at P < 0.05. Normally distributed data were presented as the mean (standard deviation), while nonnormally distributed data were presented as the median (interquartile range) (IQR, Q3-Q1).

Data availability

The publicly available datasets used in this study can be downloaded from https://github.com/drivelineresearch/openbiomechanics. The code used in the study can be obtained from the first author upon request.

References

Hernandez, V., Dadkhah, D., Babakeshizadeh, V. & Kulić, D. Lower body kinematics estimation from wearable sensors for walking and running: A deep learning approach. Gait Posture 83, 185–193 (2021).

Wang, D., Li, S., Song, Q., Mao, D. & Hao, W. Predicting vertical ground reaction force in rearfoot running: A wavelet neural network model and factor loading. J. Sports Sci. 41, 955–963 (2023).

Sun, T., Li, D., Fan, B., Tan, T. & Shull, P. B. Real-time ground reaction force and knee extension moment estimation during drop landings via modular LSTM modeling and wearable IMUs. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 3222–3233 (2023).

Xiang, L. et al. Integrating an LSTM framework for predicting ankle joint biomechanics during gait using inertial sensors. Comput. Biol. Med. 170, 108016 (2024).

Liang, Y. et al. GLSTM-DTA: Application of prediction improvement model based on GNN and LSTM. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2219, 012008 (2022).

Yuan, L., Fang, W., Xiao, H., Xiao, J., Shi, Y. & Yang, Y. Short-term traffic flow prediction by graph deep learning with spatial temporal modeling. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Smart Agriculture (ICEITSA), 172–177 (2022).

Yamak, P. T., Yujian, L. & Gadosey, P. K. A comparison between ARIMA, LSTM, and GRU for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Algorithms, Computing and Artificial Intelligence, 49–55 (Association for Computing Machinery, Sanya, 2020).

Zhu, S., Chen, J. & Su, Y. Spatio-temporal articulation and coordination co-attention graph network for human motion prediction. Signal Process. 223, 109551 (2024).

Gu, H., Yen, S. C., Folmar, E. & Chou, C. A. GaitNet+ARL: A deep learning algorithm for interpretable gait analysis of chronic ankle instability. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 28, 1–10 (2024).

Horst, F., Lapuschkin, S., Samek, W., Müller, K.-R. & Schöllhorn, W. I. Explaining the unique nature of individual gait patterns with deep learning. Sci. Rep. 9, 2391 (2019).

Xu, D. et al. A new method applied for explaining the landing patterns: Interpretability analysis of machine learning. Heliyon 10, e26052 (2024).

Mirzavand Borujeni, S., Arras, L., Srinivasan, V. & Samek, W. Explainable sequence-to-sequence GRU neural network for pollution forecasting. Sci. Rep. 13, 9940 (2023).

Cho, H., Lee, E. K. & Choi, I. S. Layer-wise relevance propagation of interactionnet explains protein–ligand interactions at the atom level. Sci. Rep. 10, 21155 (2020).

Ramsey, D. K. & Crotin, R. L. Stride length impacts on sagittal knee biomechanics in flat ground baseball pitching. Appl. Sci. 12, 995 (2022).

Escamilla, R. F., Fleisig, G. S., Groeschner, D. & Akizuki, K. Biomechanical comparisons among fastball, slider, curveball, and changeup pitch types and between balls and strikes in professional baseball pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 45, 3358–3367 (2017).

Kageyama, M., Sugiyama, T., Kanehisa, H. & Maeda, A. Difference between adolescent and collegiate baseball pitchers in the kinematics and kinetics of the lower limbs and trunk during pitching motion. J. Sports Sci. Med. 14, 246 (2015).

Werner, S. L., Suri, M., Guido, J. A. Jr., Meister, K. & Jones, D. G. Relationships between ball velocity and throwing mechanics in collegiate baseball pitchers. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 17, 905–908 (2008).

Chen, H.-H., Liu, C. & Yang, W.-W. Coordination pattern of baseball pitching among young pitchers of various ages and velocity levels. J. Sports Sci. 34, 1682–1690 (2016).

Haischer, M. H., Howenstein, J., Sabick, M. & Kipp, K. Torso kinematic patterns associated with throwing shoulder joint loading and ball velocity in little league pitchers. Sports Biomech. 23, 1–14 (2021).

Zaroug, A., Garofolini, A., Lai, D. T. H., Mudie, K. & Begg, R. Prediction of gait trajectories based on the long short term memory neural networks. PLoS ONE 16, e0255597 (2021).

Zhang, L., Soselia, D., Wang, R. & Gutierrez-Farewik, E. M. Estimation of joint torque by EMG-driven neuromusculoskeletal models and LSTM networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 3722–3731 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Opening the black box of neural networks: Methods for interpreting neural network models in clinical applications. Ann. Transl. Med. 6, 216 (2018).

Zhao, R., Wang, J., Yan, R. & Mao, K. Machine health monitoring with LSTM networks. In 2016 10th International Conference on Sensing Technology (ICST), 1–6 (2016).

Wu, H., Huang, A. & Sutherland, J. W. Layer-wise relevance propagation for interpreting LSTM-RNN decisions in predictive maintenance. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 118, 963–978 (2022).

de Swart, A. et al. Energy flow through the lower extremities in high school baseball pitching. Sports Biomech. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2022.2129430 (2022).

Albiero, M. L., Kokott, W., Dziuk, C. & Cross, J. A. Hip flexibility and pitching biomechanics in adolescent baseball pitchers. J. Athl. Train. 57, 704–710 (2022).

Ramsey, D. K., Crotin, R. L. & White, S. Effect of stride length on overarm throwing delivery: A linear momentum response. Hum. Mov. Sci. 38, 185–196 (2014).

Howenstein, J., Kipp, K. & Sabick, M. Peak horizontal ground reaction forces and impulse correlate with segmental energy flow in youth baseball pitchers. J. Biomech. 108, 109909 (2020).

Wasserberger, K., Barfield, J., Anz, A., Andrews, J. & Oliver, G. Using the single leg squat as an assessment of stride leg knee mechanics in adolescent baseball pitchers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 22, 1254–1259 (2019).

Holt, T. & Oliver, G. D. Hip and upper extremity kinematics in youth baseball pitchers. J. Sports Sci. 34, 856–861 (2016).

Culiver, A. et al. Correlation among Y-balance test–lower quarter composite scores, hip musculoskeletal characteristics, and pitching kinematics in NCAA division I baseball pitchers. J. Sport Rehabil. 28, 432–437 (2019).

Stodden, D. F., Fleisig, G. S., McLean, S. P. & Andrews, J. R. Relationship of biomechanical factors to baseball pitching velocity: Within pitcher variation. J. Appl. Biomech. 21, 44–56 (2005).

Solomito, M. J., Garibay, E. J. & Nissen, C. W. Sagittal plane trunk tilt is associated with upper extremity joint moments and ball velocity in collegiate baseball pitchers. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 6, 2325967118800240 (2018).

Fleisig, G. S., Hsu, W. K., Fortenbaugh, D., Cordover, A. & Press, J. M. Trunk axial rotation in baseball pitching and batting. Sports Biomech. 12, 324–333 (2013).

Kimura, A., Yoshioka, S., Omura, L. & Fukashiro, S. Mechanical properties of upper torso rotation from the viewpoint of energetics during baseball pitching. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 20, 606–613 (2020).

Ishida, K., Murata, M. & Hirano, Y. Shoulder and elbow kinematics in throwing of young baseball players. Sports Biomech. 5, 183–196 (2006).

Yao, Z., Yu, J., Zhang, J. & He, W. Graph and dynamics interpretation in robotic reinforcement learning task. Inf. Sci. 611, 317–334 (2022).

Wight, J., Richards, J. & Hall, S. Baseball: Influence of pelvis rotation styles on baseball pitching mechanics. Sports Biomech. 3, 67–84 (2004).

Wasserberger, K. W., Brady, A. C., Besky, D. M., Jones, B. & Boddy, K. J. The openbiomechanics project: The open source initiative for anonymized, elite-level athletic motion capture data (2022).

Diffendaffer, A. Z., Fleisig, G. S., Ivey, B. & Aune, K. T. Kinematic and kinetic differences between left-and right-handed professional baseball pitchers. Sports Biomech. 18, 448–455 (2019).

Escamilla, R. F., Slowik, J. S., Diffendaffer, A. Z. & Fleisig, G. S. Differences among overhand, 3-quarter, and sidearm pitching biomechanics in professional baseball players. J. Appl. Biomech. 34, 377–385 (2018).

Naito, K., Takagi, H., Yamada, N., Hashimoto, S. & Maruyama, T. Intersegmental dynamics of 3D upper arm and forearm longitudinal axis rotations during baseball pitching. Hum. Mov. Sci. 38, 116–132 (2014).

Liang, W. et al. Deep-learning model for the prediction of lower-limb joint moments using single inertial measurement unit during different locomotive activities. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 86, 105372 (2023).

Neilson, P. D. & Neilson, M. D. On theory of motor synergies. Hum. Mov. Sci. 29, 655–683 (2010).

Maldonado, G., Bailly, F., Souères, P. & Watier, B. On the coordination of highly dynamic human movements: An extension of the uncontrolled manifold approach applied to precision jump in parkour. Sci. Rep. 8, 12219 (2018).

Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. In Encyclopedia of Machine Learning (eds Sammut, C. & Webb, G. I.) 760–766 (Springer, 2010).

Zaroug, A., Lai, D. T. H., Mudie, K. & Begg, R. Lower limb kinematics trajectory prediction using long short-term memory neural networks. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 362 (2020).

Sawilowsky, S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 8, 597–599 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the providers of the public dataset and Shiwei Mo from Shenzhen University for their valuable suggestions on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen Yang: original draft, visualization, software. Pengfei Jin: Methodology, conceptualization; Yan Chen: editing, supervision, conceptualization. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C., Jin, P. & Chen, Y. Leveraging graph neural networks and gate recurrent units for accurate and transparent prediction of baseball pitching speed. Sci Rep 15, 7745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88284-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88284-x