Abstract

Improving the dietary quality of adolescents is crucial in public health, especially in low-income countries like Ethiopia. Despite numerous nutritional interventions, those interventions targeting adolescents were inconsistent due to fragmented implementation. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of selected double-duty interventions on the dietary diversity scores (DDS) of adolescents in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City, Central Ethiopia. A two-arm parallel cluster randomized controlled study involved 708 adolescents (356 for intervention group (IG) and 352 for control group (CG)) was conducted from October 13, 2022 to June 30, 2023. The study found a 30.4% reduction in the proportion of adolescents with low DDS in the IG along with an 18.4% increase in high DDS compared to the CG as measured by the minimum dietary diversity score indicator. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) model revealed that adolescents in the IG were nearly twice as likely to achieve a high DDS compared to the CG [AOR = 1.91, 95% CI (1.85, 1.97)]. This study highlights the effectiveness of double-duty interventions supported by behavioral models in enhancing dietary diversity and advocates for their integration into nutritional policies.

Clinical Trials: The trial was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05574842) and was first posted on October 12, 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adolescence (aged 10 to 19 years) is the transition between childhood and adulthood1. Due to melodramatically fast-tracked growth and advancement, adolescence is a decisive time in a person’s life after infancy2. Better diet quality is essential for supporting the rapid growth and developmental changes associated with puberty and brain development. Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition due to their accelerated growth and increased physiological demand for nutrients. Insufficient or excessive nutrient intake during this period can lead to various forms of malnutrition, including undernutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies3,4.

The Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) is an indicator used to assess the quality of the diet at the population level. It reflects one key aspect of diet quality, which is a micronutrient adequacy. The most important micronutrients associated with good dietary quality include eleven essential vitamins and minerals. Specifically, the vitamins include vitamin A, the B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B-6, folate, vitamin B-12), and vitamin C. The minerals covered are calcium, iron, and zinc. These nutrients are vital for the growth and cognitive development of adolescents5,6.

Diet quality encompasses multiple dimensions that are critical in understanding the causes of malnutrition. These dimensions include nutrient adequacy, food variety, and balance of food groups, all of which contribute to the overall health and nutritional status of individuals. Addressing these dimensions is essential for preventing malnutrition and promoting optimal growth and development in adolescents. Thus, improving diet quality is a key strategy in combating malnutrition7,8,9,10.

Poor diet quality, whether inadequate or excess, combined with monotonous eating habits, is one of the modifiable and immediate driving forces behind the double burden of malnutrition (DBM). It is a significant shared factor contributing to both undernutrition and overnutrition. Therefore, improving diet quality is a critical focus in efforts to combat and prevent the double burden of malnutrition11,12,13,14,15.

Evidence suggests a negative association between inadequate DDS and the DBM. Low DDS is a leading cause of undernutrition16,17,18, while the likelihood of overweight and obesity increases with higher DDS10,16,19,20. Additionally, consuming only one meal per day is associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity21. Therefore, promoting appropriate dietary diversity is crucial for DBM prevention22.

The Ethiopian healthcare system offers nutrition education to adolescents, both in schools and communities to combat malnutrition due to poor diets. However, the current efforts have been unsuccessful in improving adolescents’ nutritional behavior, likely due to inadequate implementation of double-duty nutrition interventions and the lack of integration with health behavior models23,24.

Double-duty interventions (DDIs) have the potential to improve nutritional outcomes by addressing various forms of malnutrition through integrated actions, programs, and policies. In this study, selected DDIs were enhanced through robust nutritional education and behavior change communication (NBCC). These are focused on promoting healthy diets (adequate adolescent nutrition, dietary diversity), physical activity, preventing the consumption of energy-dense foods (e.g., junk food, sugary drinks), and regulating marketing foods12,25,26.

Evidence shows that health promotions supported by behavioral models and theories can improve dietary practices by shifting unhealthy behaviors and enhancing the delivery of nutrition interventions27,28,29. In this study, adolescents were guided by a double-duty intervention packages based on Health Belief Model (HBM) constructs24,27,30,31,32. The HBM, an interactive model, effectively encourages positive health actions and behaviors. It includes six theoretical constructs: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy. The model’s effectiveness in modifying health behavior aligns with previous findings23,24,33,34,35,36,37,38,39.

Regarding the research gaps, there is a notable gap in studies focusing on the application of double-duty interventions (DDIs) using behavioral models, as well as a scarcity of interventional studies in Ethiopia40,41. This study aimed to address these gaps by applying selected DDIs to improve diet quality by enhancing dietary diversity scores. Since diet quality is a modifiable and immediate factor significantly influencing the occurrence of malnutrition, a cluster-based interventional study design was chosen to emphasize intervention than observational studies26,42.

Moreover, previous studies on improving the dietary quality of underprivileged adolescents often did not fully incorporate double-duty intervention packages and lacked support from behavioral theories43,44,45,46. To overcome these limitations and enhance the acceptance and effectiveness of the intervention packages, this study integrated constructs from the HBM. Therefore, the main objective of the study was to estimate the effect of selected double-duty interventions on the minimum dietary diversity score of adolescents using a health belief model in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City, Ethiopia, 2022/23.

Methods and materials

Study area, period, and design

This study was conducted in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City (DBRPC), Central Ethiopia, which is 130 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. It is the capital city of the North Shoa Zone of the Amhara region and was built by Emperor Zara Yakoob. It is an emerging and industrialized city. As an emerging and industrializing city, urbanization is expected to increase the population’s exposure to both sides of malnutrition, particularly to overweight and obesity. The details of the study area, period, and design were published previously47. Considering schools as a unit of randomization, a nine-month two-arm parallel design school-based cluster randomized controlled trial was conducted from October 13, 2022, to June 30, 2023.

Population, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

All adolescents in the secondary school of the city were the source population of the study, whereas adolescents in the selected school of the city were the study population during the study period. Regarding the inclusion criteria, adolescents aged 10–19 years and who had followed their teaching–learning in the selected schools and adolescents who had no intention of leaving the schools until the end of the study during the study period were included. The exclusion criteria were adolescents who were unable to respond to an interview and who had physical disabilities, including deformities such as kyphosis, scoliosis, or limb deformities that prevent them from standing erect.

Sample size determination

The Gpower 3.1.9.2 program was applied to calculate the sample size using a power of 80.5% for two independent groups, a double proportion formula, a precision (alpha) of 5%, a 10% loss to follow-up, a design effect of 2, and proportions of indicators of malnutrition (P0 = 15.8%48 and P1 = 6.2%49). Thus, the maximum calculated sample size was 648, with 324 children in the intervention group (IG) and 324 in the control group (CG), achieving a 1:1 allocation ratio. However, due to cluster randomization, the final sample size was 745 for baseline data collection and 708 for endline data collection.

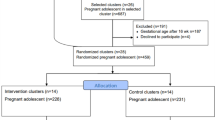

Intervention allocation, randomization, and recruitment

The intervention allocation, randomization, and recruitment of the study participants were performed in five sub cities of the DBRPC. Ten secondary schools were found in these sub cities. To prevent contamination of the message of the intervention as well as for better logistical suitability, these schools were considered clusters for the unit of randomization instead of individuals. Moreover, to avoid such information contamination, nonadjacent kebeles which contain these schools were included, and these schools were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group using a simple random method. The randomization of the schools was conducted by an independent third party to ensure that the process was free from bias. This third party was responsible for implementing a randomization protocol that ensured the intervention and control groups were assigned fairly and without any influence from the study team.

Sampling techniques and procedures

To select adolescents from the respective schools in the city, a multistage cluster sampling technique was applied. This study was conducted considering schools in the city as clusters. Of the ten schools in the city, eight are government schools and two are private schools. Of the ten schools, six schools were selected randomly and allocated to the intervention and control groups using a randomization table. The number of adolescents in each selected cluster was taken from all these school documentations. For the data collection and provision of the interventions, sections were used in the selected schools. When an eligible study participant was absent during the first visit, a revisit was conducted three times. Participants were considered nonresponsive if they missed three consecutive visits.

Intervention packages of the study and their mode of delivery

The WHO 2017 policy brief report and Hawkes et al., 2020 paper were used to modify and adopt the selected packages of the double-duty interventions. The selected packages were promoting healthy diets (adequate adolescent nutrition, dietary diversity); physical activity (do moderate intensity physical exercise, avoiding sitting for a long time); undue harm from energy-dense foods (avoiding junk processed foods, avoiding fizzy sweetened drinks, street fast foods, chips, salt, sugar, fats, etc.); and regulations on marketing foods from the customer side point of view (e.g., avoiding buying packed foods frequently). These intervention packages were given in a school-based setting through multimodal approaches within the selected intervention schools, particularly in the selected section of the students, using an NBCC tool and a theory-based HBM for at least twelve contacts. The multimodal approach was NBCC through direct contact with the students using in each school, brochures, message texts, and phone calls for their parents during the intervention period.

The intervention group was administered nutritional behavior change communication every two months, text messages every two months, and phone calls every two months for seven months duration, while the control group received the standard care provided by the health care system. The number of participants who attended the NBCC, received the message, received the phone call, and received the leaflet and had the expected frequency and attendance in the education sessions were used to measure compliance with the intervention. The details of the selected intervention packages were published previously elsewhere47.

Data collection methods, procedures, and measurements

Data collection methods and procedures

A digital data collection system was implemented using Kobo Toolbox, with a pretested and structured interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted and modified from various sources. The questionnaire was first prepared in the English language and subsequently translated into language spoken in the study area (Amharic) by language experts. Then, the questionnaire was translated back to English by an independent language expert for both languages to maintain consistency. Twelve nurses and health officers served as data collectors, while six nutritionists supervised the study. Sociodemographic variables, adolescent health, dietary practices, and HBM theoretical construct-related questions were included in the questionnaire. At baseline, sociodemographic factor data were collected, while adolescent health, dietary practice, and HBM theoretical construct-related data were measured at both baseline and end-line.

Measurements

The minimum dietary diversity score (MDDS) developed by the FAO was utilized to assess the dietary diversity score of the adolescents5. To meet the minimum dietary diversity requirement, teenagers were expected to consume at least five distinct food groups within the previous day or evening. A useful indicator of enhanced diet quality and sufficient intake of micronutrients is the percentage of teenagers in a population who fulfill this minimum criterion of consuming five food groups out of a total of ten food groups. In essence, a higher prevalence of DDSs serves as a proxy for improved micronutrient adequacy within a given population.

This study examined fourteen distinct food groups, which included cereals, white tubers, roots, legumes, seeds, and nuts; vitamin A-rich vegetables and tubers; dark green leafy vegetables; other vegetables; vitamin A-rich fruits; flesh meat; eggs; fish and seafood; and milk and milk products. These dietary categories were further divided into ten categories during the analysis period: grains, white roots and tubers; pulses (beans, peas, and lentils); nuts and seeds; milk and milk products; flesh foods (organ meat and fish); eggs; vitamin A-rich dark green leafy vegetables; other vitamin A-rich vegetables and fruits; and other vegetables and fruits5. The DDS for each adolescent was calculated based on their eating habits over the preceding 24 h. The score, which is based on 10 food groups, was categorized as high (≥ 5 food groups) or low (< 5 food groups). During the analysis, DDSs ≥ 5 food categories were categorized as “1”, and DDSs < 5 food groups were categorized as “0”.

Study variables

Improving the DDS through double-duty interventions was the dependent variable of the present study, while sociodemographic status, environmental health status, factors related to adolescent healthcare practice, factors related to adolescent diet and lifestyle, and HBM theoretical constructs were the independent variables.

Data quality control and intervention fidelity

With respect to the data quality control measures, a pretest, translation, and contextualization of the adapted and further developed English language version questionnaire into the Amharic language version were performed. Again, retranslation back to the English language was performed by a person who obtained a Master of Arts in the English language. To maintain the consistency of the two versions, a comparison was made. Translated and pretested Amharic versions of the questionnaire were used to collect the data. To test the tool (questionnaire), a pretest was administered, which was further modified next to the pretest. During the data collection period, all the details of the study were well-versed by the interviewers. All the data collectors and supervisors were trained in how to interview and supervise the data collection, respectively. During the interviews, the respondents were invigorated to feel free. The confidentiality of the responses was conserved for respondents because no information was provided publicly. Adolescents who were willing to partake and retain the informed consent document from their parents/guardians and the assent form were interviewed.

With regard to intervention fidelity, criteria were established according to the National Institutes of Health Behavioral Change Consortium recommendations50, which include checklists assessing the double-duty intervention design, training of educators, process of communication, receipt of the interventions, and enactment of skills gained from the double-duty intervention51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Equal numbers of clusters were taken from each cluster to balance the variations between different clusters in the city for both the intervention and control arms. Moreover, nonadjacent kebeles and buffer zones were used between adjacent clusters to overcome the possibility of information contamination occurring between clusters. In addition, to compare the effectiveness of the double-duty interventions, the study included a control group. In addition, for the application of the actual trial, the intervention process was pretested in an area other than the study area with a similar set of setups.

Data management and analysis methods

The lead investigator visually verified the consistency and completeness of each interview questionnaire. After the gathered data were exported to SPSS version 25, missing values and outliers were examined. Measures of central tendency, variability, percentages, and simple frequency distributions were used to characterize the respondents’ demographic, socioeconomic, and adolescent-related traits. Graphical methods (e.g., histogram), numerical methods (mean), and a statistical test (the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test because the sample size is greater than fifty) were used to verify the normality of continuous data. A chi-square test was used to compare the intervention and control groups’ baseline characteristics. The final analysis was performed with R software. A per-protocol analysis was used to include respondents who followed the established protocol in the final analysis.

The goodness of fit (or model fitness) was assessed using the Quasilikelihood under the Independence Model Criterion (QIC), which is based on a "smaller-is-better" assumptions. The QIC for the model was 1382.388 and the Corrected Quasilikelihood under the Independence Model Criterion (QICC) was 1407.631. The QIC was chosen for evaluating model fitness due to its lower value.

The difference-in-difference (DID) between the intervention and control arms was analyzed using the McNemar test, a chi-square statistical test that assesses paired nominal data, particularly for evaluating changes in responses before and after the intervention. Furthermore, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model with a binary logit function was employed to investigate the difference in changes between the intervention and control groups to assess the impact of interventions on changes in the DDS of adolescents over time. Because of repeated measurements (before and after interventions) and clustered data, this model can account for the correlation of various observations within patients. When fitting the model, the exchangeable correlation structure was considered along with the possible effects of confounding variables.

Time, intervention, time and intervention interaction, teenage sex, home garden practice, wealth index, place of residence, nutritional knowledge, ability to make decisions about food-related matters, and alcohol consumption were all considered when adjusting the model. The interaction between time and intervention was used to evaluate the intervention’s impact on the DDS. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated. A P values less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP)58. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jimma University, with ethical clearance obtained on August 10, 2022 (Reference: JUIH/IRB/104/22), prior to the start of data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant’s parent or guardian, and assent was secured from the adolescents after explaining the study’s purpose and benefits. Additionally, the trial was prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration Number: NCT05574842) and first posted on October 12, 2022.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

During the baseline data collection, 745 study participants were enrolled. At the baseline, 742 (IG = 375, CG = 367) adolescents were provided complete information and randomly assigned to the intervention or control group, whereas at the endline, 708 (IG = 356, CG = 352) respondents strictly adhered to the protocol. During the baseline data collection, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of baseline sociodemographic characteristics (P > 0.05). The detailed baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are described elsewhere15. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines were used to report the results59. A schematic of the sampling procedure for participant selection was generated based on the CONSORT guideline criteria and is described elsewhere47.

Dietary diversity scores among adolescents

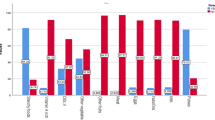

Prior to the enactment of the intervention at baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in the dietary diversity score between the intervention and control groups. After the intervention, the dietary diversity score improved more in the intervention group than in the control group at the endline period. According to the DID analysis, the reduction in the proportion of adolescents with a low DDS was greater in the intervention group compared to the control group (24.6% vs. 5.8%, P < 0.001). Similarly, the increment in the proportion of adolescents with a high DDS in the intervention group was greater than in the control group (22% vs. 3.6%, P < 0.001). Moreover, according to the overall DID analysis, the proportion of adolescents with a low DDS decreased by 30.4%, while the proportion of adolescents with a high DDS increased by 18.4% in the intervention group compared to the control group (Table 1).

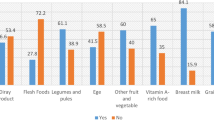

The DDS of adolescents was assessed using ten food group indicators. The consumption of these ten food groups over the previous day and night was compared by treatment group and time of measurement. At the end of the trial, the intervention group consumed higher-quality food groups compared to the control group (Fig. 1).

Effect of double duty intervention packages on dietary diversity score

To investigate the effect of the double-duty interventions on DDS, a GEE model for binary logistic regression was applied. After controlling for all possible confounding factors, the DDS showed improvement in the intervention group compared to their counterparts. In this model, adolescents in the intervention group were 1.91 times more likely to have a high DDS compared to those in the control group [AOR = 1.91, 95% CI (1.85, 1.96)]. Similarly, adolescents who completed the endline measurements were 1.28 times more likely to have a high DDS compared to those measured at baseline [AOR = 1.28, 95% CI (1.19, 1.37)]. Additionally, the interaction between the time of measurement and treatment group (time*treatment) showed a significant association with the improvement in DDS among adolescents. Adolescents in the interaction category were 11.59 times more likely to have a high DDS compared to their counterparts [AOR = 11.59, 95% CI (11.18, 12.03)] (Table 2).

Discussion

To improve diet quality and achieve a better dietary diversity score, selected double-duty intervention packages were implemented using HBM. These interventions were enhanced through robust nutrition behavior change communication (NBCC) with message texts, phone call, and leaflets.

According to the DID analysis, adolescents in the intervention group had a higher DDS than adolescents in the control group did. In this analysis, the overall proportion of low DDS was decreased by 30.4% and the overall proportion of high DDS was increased by 18.4% among the intervention than control group. This finding is consistent with the existing evidence that utilized a nutrition education and nutrition behavior change communication intervention, along with one or more packages of the double-duty intervention, to enhance the dietary status of adolescents. The effectiveness of these interventions has been supported by various studies conducted in different countries, including in Croatia on diet quality60, Bangladesh on dietary diversification61, Ghana on iron and iron-rich food intake practices62, Ethiopia on DDSs63, Ethiopia on the diet quality of children64, Ethiopia on the dietary practices of women65, Ethiopia on optimal dietary practices46, and Southwest Ethiopia on the DDS of women66. However, the present study extends beyond previous research by incorporating a more diverse range of nutritional interventions alongside physical activities specifically tailored to improve the DDS and overall dietary quality of adolescents. By implementing these comprehensive approaches, the study aims to achieve better nutritional status and effectively prevent the double burden of malnutrition.

In addition, after all possible confounding factors were controlled, the binomial generalized estimating equation (GEE) model showed an improved DDS in the intervention group compared with the control group. Adolescents in the intervention group were nearly twofold more likely to have high DDS than were those in the control group. This result aligns with previous findings, despite differences in study populations. The consistency in results suggests that, regardless of population variations, the observed effects hold true across different contexts66.

Similarly, adolescents who completed the endline measurements were nearly twofold more likely to have a high DDS than adolescents in baseline period. Similarly, the interaction between the time of measurement and treatment group had a significant association with the improvement in the DDS. Adolescents in the time of measurement and treatment group interaction category were nearly twelve times more likely to have DDS than their counterparts. A similar finding was reported in previous studies conducted among women24,66.

To enhance acceptance and uptake of the interventions, the double-duty intervention packages were guided by the HBM. As a result, the DDS of adolescents improved at endline measurements and intervention group compared to both baseline measurements and the control group, respectively. This is supported by existing evidence23,24,67,68. One possible reason for this outcome could be attributed to the utilization of the HBM constructs, which effectively enhance the acceptance and adoption of the intervention. The incorporation of the HBM constructs in the intervention could have positively influenced individuals’ perceptions, motivations, and beliefs, thereby increasing their willingness to accept and engage with the intervention.

The associations between DDS and HBM scores were compared both within and between the intervention and control groups. All HBM constructs showed significant positive correlations with the DDS. The positive correlation between the HBM constructs and DDS was supported by previous findings from Ethiopia23,24,27,36,37,39. One possible reason for the improvement in the intervention could be the utilization of the HBM. By addressing key factors such as perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy, the HBM may have played a crucial role in encouraging individuals to embrace the intervention and actively participate in it. The HBM provides a framework for understanding individuals’ beliefs and motivations related to health behaviors.

Ethiopia’s Food and Nutrition Policy (FNP) was approved to improve dietary habits, including those of adolescents69. However, it does not fully incorporate double-duty interventions aimed at enhancing adolescent dietary quality through improved diversity. Therefore, updating the policy to include these interventions is recommended to address inadequate dietary diversity among adolescents, both in the study area and nationally.

The strengths of this study include the integration of a theory-based Health Belief Model with double-duty interventions, which increased the likelihood of success. Additionally, the intervention was delivered using a multimodal approach, including text messages, phone calls, and behavior-change communication. However, limitations include recall bias, social desirability, and reporting bias were expected. These biases were minimized by thoroughly explaining the process to participants, probing for details, and ensuring accurate reporting.

Conclusion

In this study, compared with those in the control group, the dietary diversity scores of the intervention group of adolescents significantly improved. This improvement can be attributed to the implementation of the double-duty intervention accompanied by the utilization of the health belief model. Compared with the control group, the intervention group led to a substantial decrease of nearly one-third in the overall proportion of respondents with a low DDS and a significant increase of almost one-fifth in the overall proportion of respondents with a high DDS among the intervention group. These findings indicate that the intervention had a considerable impact on improving the dietary diversity of the participants. Furthermore, when potential confounding factors were controlled for using the generalized estimating equation model, adolescents in the intervention group demonstrated a substantial improvement in their DDS at the end of the measurement period. This finding suggested that the observed improvement in dietary diversity was directly associated with the intervention and not influenced by other variables. Based on these findings, double-duty interventions, accompanied by the incorporation of the health belief model, are recommended to be integrated into national guidelines as part of the country’s overall strategy and nutrition policy. By doing so, the potential benefits of these interventions can be extended to a larger population, leading to improved dietary diversity and better nutritional outcomes among adolescents on a national scale.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

WHO. Guideline: Implementing Effective Actions for Improving Adolescent Nutrition. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260297/9789241513708-eng.pdf%0Ajsessionid=19D1CBFA434795BA1645CC009FFE99A4?sequence=1. (Accessed on June 10, 2021) (2018).

Azzopardi, P. S. et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. Lancet. 393(10176), 1101–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9 (2019).

Das, J. K. et al. Nutrition in adolescents: Physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1393(1), 21–33 (2017).

Nicholson, A., Fawzi, W., Canavan, C., Keshavjee, S. Advancing Global Nutrition for Adolescent and Family Health: Innovations in Research and Training. Proceedings of the Harvard Medical School Center for Global Health Delivery–Dubai. 2018, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. 1–75 (2018).

FAO. Minimum dietary diversity for women: an updated guide for measurement: from collection to action. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb3434en. 1–176 (2021)

Getacher, L., Egata, G., Alemayehu, T., Bante, A., Molla, A. Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among lactating mothers in ataye district, North Shoa zone, central Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Metab. (2020).

Berhane, H. Y., Tadesse, A. W., Noor, A., Worku, A., Shinde, S., Fawzi, W. Food environment around schools and adolescent consumption of unhealthy foods in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Matern. Child Nutr. (e13415):1–10 (2023).

Pries, A. M., Huffman, S. L., Champeny, M., Adhikary, I., Benjamin, M., Coly, A. N., et al. Consumption of commercially produced snack foods and sugar-sweetened beverages during the complementary feeding period in four African and Asian urban contexts. Matern. Child Nutr. 13 (2017).

Getacher, L., Ademe, B. W. & Belachew, T. Lived experience and perceptions of adolescents on prevention, causes and consequences of double burden of malnutrition in Debre Berhan City, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 337–356 (2023).

Paulo, H. A. et al. Role of dietary quality and diversity on overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Tanzania. PLoS One. 17(4 April), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266344 (2022).

IFPRI. Global Nutrition Report 2015: Actions and accountability to advance nutrition & sustainable development. Washington, DC. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/global-nutrition-report-2015 (Accessed on July 13, 2021) (2015).

WHO. Double-duty actions for nutrition. Policy Brief. Department of Nutrition for Health and Development World Health Organization. Geneva. Switzerland. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255414/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.2-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed on June 10, 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255414/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.2-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed on June 10, 2021) (2017).

Development Initiatives. Global Nutrition Report 2017: Nourishing the SDGs. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives. 21. Available from: http://165.227.233.32/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Report_2017-2.pdf (Accessed on July 13, 2021) (2017).

Wells, J. C. et al. The double burden of malnutrition: Aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet 395(10217), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32472-9 (2020).

Getacher, L., Ademe, B. W. & Belachew, T. Double burden of malnutrition and its associated factors among adolescents in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City, Ethiopia : A multinomial regression model analysis. Front. Nutr. 10, 1–13 (2023).

Harper, A., Goudge, J., Chirwa, E., Rothberg, A., Sambu, W., Mall, S. Dietary diversity, food insecurity and the double burden of malnutrition among children, adolescents and adults in South Africa: Findings from a national survey. Front. Public Heal. 10 (2022).

Olumakaiye, M. F. Dietary diversity as a correlate of undernutrition among school-age children in southwestern Nigeria. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 37(1) (2013).

Gassara, G. & Chen, J. Household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and stunting in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. Nutrients 13, 4401. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu1312440.Nutrients.2021;13(4401) (2021).

Golpour-Hamedani, S., Rafie, N., Pourmasoumi, M., Saneei, P. & Safavi, S. M. The association between dietary diversity score and general and abdominal obesity in Iranian children and adolescents. BMC Endocr. Disord. 20(1), 1–8 (2020).

Karimbeiki, R. et al. Higher dietary diversity score is associated with obesity: a case–control study. Public Health 157(March), 127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.028 (2018).

Zalewska, M. & Maciorkowska, E. Dietary habits and physical activity of 18-year-old adolescents in relation to overweight and obesity. Iran J. Public Health 48(5), 864–872 (2019).

de Oliveira Otto, M. C. et al. Dietary diversity: Implications for obesity prevention in adult populations: A science advisory from the American heart association. Circulation 138(11), e160–e168 (2018).

Diddana, T. Z., Kelkay, G. N., Dola, A. N. & Sadore, A. A. Effect of nutrition education based on health belief model on nutritional knowledge and dietary practice of pregnant women in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia: A cluster randomized control trial. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018(1), 6731815 (2018).

Demilew, Y. M., Alene, G. D. & Belachew, T. Effect of guided counseling on dietary practices of pregnant women in West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 15(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233429 (2020).

Hawkes, C., Ruel, M. T., Salm, L., Sinclair, B. & Branca, F. Double-duty actions: seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. The Lancet 395, 142–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32506-1 (2020).

Hawkes, C., Demaio, A. R. & Branca, F. Double-duty actions for ending malnutrition within a decade. The Lancet Global Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30204-8 (2017).

Dansa, R., Reta, F., Mulualem, D., Henry, C. J. & Whiting, S. J. A nutrition education intervention to increase consumption of pulses showed improved nutritional status of adolescent girls in Halaba special district, Southern Ethiopia. Ecol. Food Nutr. 58(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2019.1602042 (2019).

Sirajuddin, S., Syafar, M., Adhayani, Z. & Arda, R. The effect of nutritional education on adolescent fruit vegetable eating patterns, based on planned behavior theory. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils 8(6), 1750–1759 (2021).

Warren, A. M., Frongillo, E. A., Nguyen, P. H. & Menon, P. Nutrition intervention using behavioral change communication without additional material inputs increased expenditures on key food groups in bangladesh. J. Nutr. 150(5), 1284–1290 (2020).

Omer, A. M., Haile, D., Shikur, B., MacArayan, E. R. & Hagos, S. Effectiveness of a nutrition education and counselling training package on antenatal care: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Addis Ababa. Health Policy Plan. 35, I65-75 (2020).

Shrestha, R. Behaviour change interventions and child nutritional status. Evidence from the promotion of improved complementary feeding practices. Infant and young child nutrition project (2011).

Sakalik, L. M. Frequency of nutrition counseling in an overweight and obese adolescent urban population and its effect on health related outcomes (2015).

Boskey, E. The health belief model. Available at: https://www.verywellmind.com/health-belief-model-3132721 (Accessed on October 12, 2021)). 211–4 (2020).

Mohamed, N. C., Moey, S. F. & Lim, B. C. Validity and reliability of health belief model questionnaire for promoting breast self-examination and screening mammogram for early cancer detection. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 20(9), 2865–2873 (2019).

Glanz, K. & Bishop, D. B. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 31, 399–418 (2010).

Tariku, B., Whiting, S. J., Mulualem, D. & Singh, P. Application of the health belief model to teach complementary feeding messages in Ethiopia application of the health belief model to teach. Ecol. Food Nutr. 54(5), 572–582 (2015).

Naghashpour, M., Shakerinejad, G., Lourizadeh, M. R., Hajinajaf, S. & Jarvandi, F. Nutrition education based on health belief model improves dietary calcium intake among female students of junior high schools. J. Heal Popul. Nutr. 32(3), 420–429 (2014).

Sharifirad, G. R., Tol, A., Mohebi, S., Matlabi, M. & Shahnazi, H. The effectiveness of nutrition education program based on health belief model compared with traditional training. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2(March), 1–5 (2013).

Tavakoli, H. R., Dini-Talatappeh, H., Rahmati-Najarkolaei, F., Fesharaki, M. G. Efficacy of HBM-based dietary education intervention on knowledge, attitude, and behavior in medical students. Iran Red Crescent Med. J. 18(11) (2016).

Getacher, L., Ademe, B. W. & Belachew, T. Mapping the national evidence on double burden of malnutrition in Ethiopia: A protocol of scoping review. BMJ Open 13(12), 1–12 (2023).

Getacher, L., Ademe, B. W. & Belachew, T. Understanding the national evidence on the double burden of malnutrition in Ethiopia for the implications of research gap identifications: A scoping review. BMJ Open 13(12), 1–12 (2023).

Hawkes, C., Ruel, M., Wells, J. C., Popkin, B. M. & Branca, F. The double burden of malnutrition—further perspective—Authors’ reply. Lancet. 396(10254), 815–816 (2020).

Van Cauwenberghe, E. et al. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: Systematic review of published and grey literature. Br. J. Nutr. 103(6), 781–797 (2010).

Mohebi, S., Parham, M., Sharifirad, G. & Gharlipour, Z. Effect of educational intervention program for parents on adolescents’nutritional behaviors in Isfahan in 2016. J. Educ. Health Promot. 6(January), 1–6 (2017).

Saaka, M., Wemah, K., Kizito, F. & Hoeschle-Zeledon, I. Effect of nutrition behaviour change communication delivered through radio on mothers’ nutritional knowledge, child feeding practices and growth. J. Nutr. Sci. 10, e44 (2021).

Tamiru, D. et al. Effect of integrated school-based nutrition education on optimal dietary practices and nutritional status of school adolescents in Southwest of Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health. 29(6), 1–12 (2017).

Getacher, L., Ademe, B.W., Belachew, T. Effect of double-duty interventions on double burden of malnutrition among adolescents in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City, Ethiopia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. Science, 13, e74. (2024).

Hadush, G., Seid, O. & Wuneh, A. G. Assessment of nutritional status and associated factors among adolescent girls in Afar, Northeastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 40(1), 2 (2021).

Gebreyohannes, Y., Shiferaw, S., Demtsu, B. & Bugssa, G. Nutritional status of adolescents in selected government and private secondary schools of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 3(6), 504 (2014).

Bellg, A. J. et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Heal Psychol. 23(5), 443–451 (2004).

Murphy, S. L. & Gutman, S. A. Intervention fidelity: A necessary aspect of intervention effectiveness studies. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 66(4), 387–388 (2012).

Borrelli, B. The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. J. Public Health Dent. 71(SUPPL. 1) (2011).

Gearing, R. E. et al. Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007 (2011).

Campbell, B. K. Fidelity in public health clinical trials: Considering provider-participant relationship factors in community treatment settings. J. Public Health Dent. 71(SUPPL. 1), 64–65 (2011).

Borrelli, B. et al. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73(5), 852–860 (2005).

Toomey, E. The implementation fidelity of infant feeding interventions to prevent childhood obesity: A systematic review Dr Elaine Toomey National University of Ireland Galway (2017).

Demilew, Y. M., Alene, G. D. & Belachew, T. Effects of guided counseling during pregnancy on birth weight of newborns in West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 20, 1–12 (2020).

World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects: 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013. 10 (2013). Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G. & Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 8(18), 1–9 (2010).

Kendel Jovanović, G., Janković, S. & Pavičić Žeželj, S. The effect of nutritional and lifestyle education intervention program on nutrition knowledge, diet quality, lifestyle, and nutritional status of Croatian school children. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1019849 (2023).

Nyma, Z. et al. Dietary diversity modification through school-based nutrition education among Bangladeshi adolescent girls: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 18(3 March), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282407 (2023).

Wiafe, M. A., Apprey, C. & Annan, R. A. Nutrition education improves knowledge of iron and iron-rich food intake practices among young adolescents: A nonrandomized controlled trial. Int. J. Food Sci. 2023(1), 1804763 (2023).

Tamiru, D. et al. Improving dietary diversity of school adolescents through school based nutrition education and home gardening in Jimma Zone: Quasi-experimental design. Eat. Behav. 23, 180–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.10.009 (2016).

Tessema, M., Hussien, S., Ayana, G., Teshome, B., Hussen, A., Kebebe, T., et al. Effect of enhanced nutrition services with community-based nutrition services on the diet quality of young children in Ethiopia. Matern. Child Nutr.1–11 (2023).

Gebremichael, M. A. & Lema, T. B. Effect of behavior change communication through the health development army on dietary practice of pregnant women in Ambo district, Ethiopia: A cluster randomized controlled community trial. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 05(03), 225–237 (2022).

Tsegaye, D., Tamiru, D. & Belachew, T. Theory-based nutrition education intervention through male involvement improves the dietary diversity practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in rural Illu Aba Bor Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study. Matern. Child Nutr. 18(3), 1–14 (2022).

Bagherniya, M. et al. Obesity intervention programs among adolescents using social cognitive theory: A systematic literature review. Health Educ. Res. 33(1), 26–39 (2018).

Tsegaye, D., Tamiru, D. & Belachew, T. Effect of a theory-based nutrition education intervention during pregnancy through male partner involvement on newborns’ birth weights in Southwest Ethiopia. A three-arm community based Quasi-Experimental study. PLoS One 18(1 January), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280545 (2023).

FDRE. Food and Nutrition Policy. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Available from: https://www.nipn.ephi.gov.et/sites/default/files/2020-05/FoodandNutritionPolicy.pdf (Accessed on July 26, 2021) (2018).

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Jimma University and Debre Berhan University for their funding support. We are also deeply grateful to the study participants, data collectors, supervisors, language translators, office administrators, and everyone else who contributed, directly or indirectly, to the successful completion of this study.

Funding

Jimma University and Debre Berhan University fund this study through minister of education of Ethiopia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG: Participated in the conception and design of the study, performed the data collection, performed the statistical analysis and served as the lead author of the manuscript. BWA and TB: Participated in the design of the study, revised subsequent drafts of the paper, support statistical analysis, critically reviewing and finalization of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Getacher, L., Ademe, B.W. & Belachew, T. Effect of double duty interventions on dietary diversity score of adolescents using a cluster randomized controlled trial in Debre Berhan Regiopolitan City, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 5381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88324-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88324-6