Abstract

Brass (Cu–Zn alloy) used in the crescent of the Al-Maradani Mosque pulpit is subjected to corrosion under certain conditions, such as exposure to polluted air, oxidizing acids, and compounds containing sulphur or ammonia. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of palm kernel oil extract (PKO) as a green corrosion inhibitor for protecting brass artifacts. The crescent was analyzed using metallographic microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) to identify its alloy composition, microstructure and corrosion products. The analyses confirmed the crescent was made of a brass alloy (Cu–Zn) and formed by hammering, with corrosion layers composed primarily of cuprite and clinoatacamite, covered by dust containing calcite and quartz. The corrosion protection efficiency of the PKO was evaluated using brass coupons, simulating the artifact of the alloy. Electrochemical methods, including the open circuit potential (OCP), Tafel, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), were used to assess the performance of palm kernel oil on brass coupons at different concentrations (1, 3, 5, 7%). Electrochemical tests showed that corrosion inhibition efficiency increased with higher palm kernel oil concentrations, with the 7% concentration exhibiting the highest corrosion protection, up to 99.7%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corrosion poses a significant threat to the preservation of metallic artifacts, especially those in uncontrolled environments where it is difficult to eliminate. As a result, corrosion prevention is a priority in the conservation of cultural and archaeological heritage. Among the various methods used to combat corrosion, the application of inhibitors has proven to be one of the most effective strategies1,2,3,4,5.

In recent years, the focus has shifted towards the use of green corrosion inhibitors due to their eco-friendly nature and cost-effectiveness. Green corrosion inhibitors, particularly those derived from natural plant extracts, have shown great promise in protecting metals by forming a protective barrier that blocks active sites on the metal surface, thereby mitigating interaction with corrosive elements6,7,8,9,10,11,12. The advantages of using plant extracts as corrosion inhibitors are manifold: they are biodegradable, non-toxic, inexpensive, and readily available. Additionally, they do not pose risks to human health or the environment, unlike many synthetic inhibitors13,14,15. There is a wide range of phytochemicals, such as tannins, flavonoids, and polyphenols, so it has a high potential for corrosion inhibition. The first use of a plant extract as a corrosion inhibitor dates back to 1930 when it was the extract of Chelidonium majus and some other plants in a pickling bath of H2SO416,17.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of different natural plant extracts and oils as corrosion inhibitors for the protection of copper and its alloys. Examples include Watermelon Seed Extract as a green corrosion inhibitor, which highlighted the effectiveness of watermelon seed extract in saline environments18. Jatropha Extract for bronze alloy corrosion, which exhibited up to 90% efficiency through adsorption mechanisms in neutral media19. Avocado Seed Extract, achieving an inhibition efficiency of 87% for aluminum alloys in saline solutions through the formation of a protective passive layer20. Mint Leaf Extract and NiO Nanoparticles, demonstrating high inhibition efficiencies on copper surfaces21. Aqueous Extract of Pointed Gourd Seeds (PGS), which achieved corrosion protection for mild steel22. Mint Leaf Water Extract for copper corrosion, showing effective mitigation of copper corrosion23. Opuntia Dillenii Seed Oil provides excellent inhibition efficiency of 99% for iron in acidic rain solutions by forming a barrier layer through chemisorption and physisorption24.

Plant extracts contain various biologically active components, such as terpenes, alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds; otherwise, oils contain a mixture of fatty acids and other compounds, which are known for their corrosion-inhibiting properties. These compounds adsorb onto the metal surface, creating a protective film that acts as a physical barrier against corrosive agents. Despite the natural tendency of plant extracts to biodegrade, this issue can be mitigated by adding biocides, which prevent decomposition and extend the useful life of the inhibitors. The use of natural substances, particularly vegetable oils, as corrosion inhibitors has gained increasing attention. Vegetable oils are appealing due to their low cost, abundant availability, and environmental friendliness. Among them, palm kernel oil (PKO) stands out as a particularly effective inhibitor. Derived from the seed of the palm fruit, palm kernel oil is distinct from palm oil in its composition, being richer in saturated fatty acids and containing a high concentration of lauric acid. These properties make PKO more solid at room temperature and enhance its ability to form a stable, protective layer on metal surfaces16. Research into the use of palm kernel oil as a corrosion inhibitor has demonstrated its high efficacy in protecting metals and alloys. It is a potentially non-toxic, abundantly available, and environmentally friendly natural product. Studies have shown that palm kernel oil, when applied as a corrosion inhibitor, can achieve an inhibition efficiency of up to 97.20% under optimal conditions, which include an inhibitor concentration of 1.00 g/l, a 4-day exposure period, and a temperature of 40 °C25,26,27.

Electrochemical techniques have a long history in conservation-restoration treatments for metallic cultural heritage, particularly the use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). EIS is well-established for evaluating protective coatings and is especially suited for testing coatings on metallic works of art. It helps assess parameters such as corrosion inhibition efficiency and surface coverage by inhibitor films. This technique, which measures changes in polarization resistance (Rp) and electrode capacitance, has been widely used since the early 1990s to quantify the protective effectiveness of coatings against metal corrosion, providing valuable insights for the preservation of cultural heritage28,29,30,31,32,33.

This study aimed to evaluate palm kernel oil (PKO) as a green corrosion inhibitor for protecting brass artifacts, specifically the Al-Maradani Mosque pulpit, from corrosion. Additionally, it involved the investigation and characterization of the brass artifact. The research offers valuable insights into the conservation of cultural heritage materials using environmentally friendly additives.

Material and methods

Case study

The crescent atop the pulpit (minbar) of the Mosque of Amir Altinbugha al-Maridani, dating from 1340 CE during the Mamluk Sultanate in Cairo, Egypt, is crafted from Brass, a copper-zinc alloy. It features a circular base that rests on the dome above the minbar. From the base, a short neck leads to an elongated oval body that tapers upward. Another short neck supports two flattened circles, which are topped by a larger neck. The structure is crowned with a circle that has a wide opening, completing the design (Fig. 1a). The crescent, often placed atop domes, minarets, or the pavilion above the pulpit (minbar), is aligned parallel to the direction of the Qibla (Fig. 1b). The Ottomans were the first to introduce the crescent on minarets during the reign of Sultan Selim I, initially to differentiate mosques from churches. The crescent was positioned on the highest part of the minaret, a practice that has continued ever since. Within the mosque, the Qibla is indicated by the Mihrab, while outside, it is marked by the opening of the crescent. This is the purpose and significance of placing the crescent34. The Minbar is crowned by a horseshoe arch and surmounted by a dome supported by four columns, which culminate in a brass crescent (called Hilal in Arabic). The crescent weighs approximately 5780 g. Figure 2 illustrates the dimensions of the meter. It is about 104 cm in length, with a maximum width of 22 cm at its center and a diameter of approximately 11 cm at the base of the opening. The crescent’s opening has a diameter of roughly 20 cm.

The crescent was examined using various techniques to explore its alloy composition and degradation process. Surface morphology was analyzed with a Quanta FEG250 (Japan) environmental scanning electron microscope, while the alloy’s microstructure was studied using an OLYMPUS BX41M-LED metallographic microscope. Corrosion products and surface calcifications were assessed with a PANalytical X’Pert Pro X-ray diffraction system. The elemental composition of the crescent was determined using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) attached to the Quanta FEG250 SEM.

Corrosion test

Coupons preparation

For the simulation experiments, brass sheets (1 cm width × 5 cm length × 0.2 cm thickness) were prepared based on the chemical composition of the real brass crescent (Cu–Zn alloy). Each coupon was numbered and stamped with punches for identification. The coupons were initially polished using different grades of emery papers, rinsed with running and distilled water, then cleaned with ethyl alcohol, and thoroughly dried. Finally, they were stored in a dry environment to prevent corrosion before the experiments4.

Palm kernel oil (PKO)

The palm kernel oil (PKO) was commercially sourced from KEMATECH-ALEX, Alexandria, Egypt. Typically, PKO is prepared by first drying and then grinding the palm kernels into a fine powder. The powder is then soaked in ethanol solution for 24 h to achieve a homogenous mixture, after which the extract is collected. Any residual ethanol is removed through evaporation, leaving the filtrate to be used as an inhibitor in its purest form27.

Gas chromatography analysis

Gas Chromatography (GC) was employed to screen the biochemical composition, including major and minor components, of commercially produced palm kernel oils. The oil was first diluted to a 1:200 ratio with hexane to prepare it for injection. The analysis was carried out using an Agilent 7890B GC system, equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID), at the Central Laboratories Network, National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt. Separation was performed on a Zebron ZB-FAME column (60 m × 0.25 mm internal diameter × 0.25 μm film thickness). The gas chromatography analysis was carried out using hydrogen as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.8 ml/min. The injection volume was 2 µL, operating in split mode (1:10). The temperature program began with an initial oven temperature of 100 °C, held for 3 min, followed by a 2.5 °C/min increase until reaching 240 °C, which was maintained for 10 min. The injector temperature was set to 250 °C, while the flame ionization detector (FID) was held at 285 °C.

Preparation of (PKO) as a corrosion inhibitor

Palm kernel oil (PKO) was diluted in a controlled manner to achieve specific concentrations for electrochemical measurements. A PKO stock solution was prepared by mixing 5 ml acetone and 5 ml ethyl alcohol, to which 10 ml of PKO was added, ensuring proper dissolution.1, 3, 5, and 7% of the stock solution was used. The working electrolyte stock consisted of a 3.5% Sodium Chloride solution.

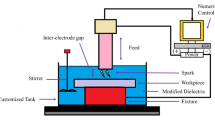

Electrochemical tests

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using an Origaflex-OGF01A (Origalys, France) system. The setup included an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a platinum sheet as the auxiliary electrode, and a brass sheet as the working electrode. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted at open circuit potential (OCP), while Tafel plots were used to determine the corrosion rate (C.R.) and corrosion current density (Icorr.) at a scan rate of 2 mV/s within a potential range of -300 to 300 mV. EIS measurements were performed over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz with a 10 mV amplitude, following the ASTM G106-89 standard. A 3.5% NaCl solution, prepared with triple-distilled water, served as the electrolyte for the corrosion testing. Each electrochemical measurement was conducted in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Results and discussion

Brass crescent

Brass, an alloy of (copper-zinc), is highly valued for combining the beneficial properties of both metals and is widely used in various fields. Historically, techniques like smoothing and hammering brass were essential in crafting items such as crescents. Manufacturers skillfully utilized hammers, anvils, and precise procedures to form the desired shapes. Soldering played a crucial role in Crescents’ manufacturing process. Copper plates were hammered on an anvil, and the ends of the plate were joined together by solder. Brass soldering, a solid joint of copper and zinc, ensured durability. In brass artifact manufacturing, this tradition continues, where the brass sheet is flattened, hammered, and soldered using hard solder to create robust and finely shaped artifacts35,36.

Copper and its alloys generally exhibit high resistance to atmospheric corrosion due to the formation of protective layers of corrosion products, which slow down the rate of attack. The thickness and composition of these corrosion layers are influenced by environmental factors such as relative humidity and pollution levels. Figure 3 illustrates the extent of damage to the brass crescent. The crescent is heavily covered with dust and dirt, indicating prolonged exposure to environmental elements. The presence of these surface contaminants can accelerate corrosion processes.

Alloy microstructure

The microstructure of ancient brass alloys typically consists of a combination of α-phase (copper-rich) and β-phase (zinc-rich) regions, with varying proportions depending on the zinc content, often exhibiting grain boundaries and inclusions that reflect the alloy’s historical manufacturing techniques and usage (Fig. 4). Brass is classified by its phase: alpha brass (up to 35% zinc), α + β Brass (35–46.6% zinc), and beta brass (46.6–50.6% zinc). Alloys with more than 50% zinc are generally avoided due to the brittle δ phase, as the beta phase is harder than alpha, can endure little cold work, and becomes more malleable above 470 °C. Alpha Brass, found in most ancient alloys, is ductile, easily cold-worked, and has good corrosion resistance, which is advantageous for the longevity and preservation of artifacts. Based on the EDS analysis, the brass alloy of the crescent, containing approximately 33.65% zinc, falls within the category of alpha brass, which is characterized by a single-phase microstructure (α-phase) that is ductile and has good cold-working properties. The microstructure confirmed a homogeneous alpha brass microstructure without the presence of the (β-phase), with the alpha phase typically showing a face-centred cubic (FCC) structure that contributes to the alloy’s ductility and workability37,38,39,40,41.

Alloy chemical composition

SEM examination of the brass crescent revealed zinc white globules dispersed throughout the alloy, along with stress corrosion cracking (SCC), resulting in small, scattered cracks (Fig. 5). SCC is particularly common in Brass, occurring under tensile stress in polluted (industrial) environments, especially those containing ammonium compounds. This phenomenon typically affects copper alloys with 20% or more zinc but is less common in other alloys42.

EDS analysis was performed to determine the chemical composition of the alloy that made up the crescent. The results revealed that the crescent was made of a brass alloy containing 64.77% Cu, 33.65% Zn, and 1.58% Sn, as shown in Fig. 6 and Table 1. Yellow brass alloys typically contain 23–41% zinc, with up to 3% lead and 1.5% tin as additional alloying elements.

Corrosion degradation

It is well known that brasses are copper-zinc alloys that are extensively used in many fields, and they combine many of the favourable features of both copper and zinc. Since zinc is the active component of brass, it tends to corrode, leaving its surface enriched with copper. The corrosion of a metal is often considered an inconvenience because it implies a change in the objects over the course of time. This damage is caused to metal by chemical, electrochemical, or even biological reactions between metal and the surrounding medium43. Selective corrosion occurs when one component of an alloy, such as zinc in copper-zinc alloys, dissolves preferentially, resulting in a weakened, porous, copper-rich structure. This process, known as dezincification, transforms the material into spongy copper, increasing its susceptibility to corrosion cracking. Dezincification typically affects alloys with zinc content above 15 wt.%, where copper re-precipitates after both metals dissolve44.

The electrical potential difference between copper and zinc, in the presence of water, oxygen, and impurities, leads to intergranular corrosion in Brass, weakening it and making it prone to stress damage. Reshaping without prior heat treatment can cause distortion, especially if microcracks are present. The corrosion rate is further influenced by the contact between metals of different electrochemical potentials, where the less noble metal becomes anodic and corrodes more rapidly41.

X-ray diffraction of corrosion products and dust accumulated on the crescent revealed the presence of various corrosion compounds, such as malachite, atacamite, and chalcopyrite, and compounds resulting from dust and dirt, such as gypsum and quartz, as shown in Fig. 7, and Table 2. The brass crescent is exposed to varying humidity, temperature fluctuations, and contaminants, all of which contribute to the formation of these compounds, leading to accelerated deterioration and possible damage to the metal over time.

Malachite (Cu2CO3(OH)2), a basic copper carbonate, forms when copper in the brass alloy reacts with carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere and moisture. The reaction typically occurs in outdoor environments where CO2 levels are elevated, leading to the formation of malachite as a green corrosion product. Atacamite (Cu2Cl(OH)3) is a basic copper chloride that forms in the presence of chloride ions, which can originate from salt in the air or from pollution. Chloride ions penetrate the brass surface, reacting with the copper and moisture to form atacamite. This compound is often associated with aggressive, localized corrosion and pitting. Chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), a copper iron sulphide, can form in the presence of sulphur compounds, which are common in industrial environments due to pollution from combustion processes. Sulfur reacts with copper and iron present in the alloy, leading to the formation of chalcopyrite. This process is often accelerated by the presence of moisture and acidic conditions. Gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) and quartz (SiO2) are not direct corrosion products of Brass but result from the accumulation and calcification of dust and dirt on the surface of the crescent. Gypsum forms from the reaction of calcium in the dust with sulphur dioxide (SO2) in the atmosphere, especially in polluted environments. Quartz, being a common mineral in dust, can become embedded in the corrosion layers over time45,46.

Bird excrements, beyond their impact on the aesthetic appearance of brass objects, can cause chemical damage. Due to their acidic nature—primarily from uric acid—these droppings react with copper in Brass, forming corrosive salts that promote corrosion (Fig. 3). Additionally, bird excreta retain moisture, facilitating electrochemical reactions that accelerate corrosion. Additionally, the organic material in the droppings breaks down over time, producing more acids that further attack the copper surface. This can result in localized corrosion, patina formation, and even crevice corrosion if the droppings are left on the metal for extended periods47,48,49.

Chemical composition of PKO

The chromatogram from the GC analysis identified various fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) in the palm kernel oil sample. The key components and their retention times (RT), peak areas, and relative percentages are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 8. Fatty acids, such as palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0), and oleic (18:1), are common in animal and vegetable fats and oils. Unlike palm oil, which contains balanced amounts of saturated and unsaturated fats, palm kernel oil is primarily saturated. It is rich in lauric acid, myristic acid, palmitic acid, and oleic acid50.

The gas chromatography analysis revealed that the palm kernel oil primarily consists of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs), with several peaks indicating the presence of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The highest concentration components include Peak 4, representing 52.63% of the total area, which is likely a major saturated fatty acid such as lauric acid commonly found in palm kernel oil. The composition aligns with the typical profile of commercial palm kernel oil, which is rich in medium-chain fatty acids (such as lauric and myristic acids) known for their stability and beneficial properties in various industrial applications. Given the oil’s chemical composition, the commercially sourced oil appears to be of good quality and suitable for use as a corrosion inhibitor as tested in electrochemical experiments. Commercial palm kernel oil already meets the necessary standards for performance, containing the essential fatty acid profile.

Corrosion tests

The study evaluated how corrosion attack was affected by adding and increasing the concentration of PKO inhibitor to a brass alloy51. The corrosion behavior of the samples in a NaCl-based solution, as determined by EIS and the corresponding electrical circuit model, is shown in Fig. 9a–c. The data reveal that D (7%) exhibits the highest corrosion resistance, followed by C (5%), B (3%), and A (1%) as the least effective. Table 4 presents the reference parameters derived from EIS fitting plots, as shown in Fig. 9b, using manual adjustments in Zview software for PKO samples with varying concentrations. The results confirm that all PKO samples (A–D) demonstrate superior corrosion resistance compared to the blank. The dense and stable surface of the PKO samples likely contributes to their high corrosion resistance, reflected by the larger capacitive response (Fig. 9). In contrast, the blank sample experienced significant deterioration due to the formation of a corrosion product layer on its surface, further highlighting the effectiveness of PKO in corrosion inhibition.

(a) Nyquist plots, (b) EIS fitting plots for PKO samples with varying concentrations, (c) the equivalent electrical circuit model, (d) Bode impedance plots understanding the corrosion behavior of Brass in a 3.5% sodium chloride solution both with and without various concentrations of palm kernel oil as a corrosion inhibitor.

The bigger capacitive response suggests that the D sample (highest concentration of PKO 7%) dense and stable surface may offer significant protection against corrosive environments. The Nyquist plots align with the bode impedance measurements, showing consistent behavior, as shown in Fig. 9c. The efficacy of palm kernel oil (PKO) as a corrosion inhibitor for Brass in a 3.5% NaCl solution at room temperature is clearly trended by the electrochemical data in Tables 4 and 5. In Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), the fitting results include key parameters such as Rs (solution resistance) and Rp (polarization resistance), which are inversely related to Icorr.. CPE-T and CPE-P are parameters of the Constant Phase Element (CPE) that provide detailed insights into the electrochemical behavior, as summarized in Table 4. The chi-squared value evaluates the fit quality between experimental and modelled data, with lower values indicating a better fit and closer alignment between measured and simulated impedance values. The sum of squared residuals, derived from differences between observed and predicted values, typically varies, but values nearing zero signify excellent model performance, as demonstrated in Table 4 for all PKO samples, which reveal notable electrochemical behavior. Wo1-T, Wo1-R, and Wo1-P are specific parameters of a finite-length Warburg element. Wo1-R represents the resistance associated with the solid electrolyte interface and charge-transfer processes. Wo1-T corresponds to the diffusion layer thickness, influencing ion movement through the electrolyte. Wo1-P, an exponent modifying the phase angle, reflects deviations from ideal diffusion behavior due to changes in the electrolyte. These parameters offer a comprehensive understanding of the system’s electrochemical dynamics.

As a result, by raising the concentration, inhibitor addition lowers the electrochemical activity on the metal surface up to 99.7% corrosion inhibition at optimal levels51. Additionally, these protective layers by (PKO) reduce the dissolution of brass ions in aggressive environments, significantly slowing corrosion rates52. Palm kernel oil (PKO) prevents corrosion in copper alloys principally by adsorbing onto the metal surface, thereby slowing electrochemical processes and reducing the likelihood of pitting, cracking, and void formation. This mechanism involves PKO molecules forming a protective barrier that restricts the passage of corrosive ions to the metal surface while also preventing metal ions from dissolving into the solution51. The effectiveness of PKO as a corrosion inhibitor lies in its ability to alter the electrochemical properties at the metal-solution interface, leading to significantly reduced corrosion rates52.

Samples with and without varying concentrations of PKO were analyzed to investigate the corrosion mechanism. Corrosion parameters, including current density (Icorr.), anodic Tafel slope (βa), cathodic Tafel slope (− βc), and corrosion potential (Ecorr.), were determined using the Tafel extrapolation method.

The corrosion rate was ascertained using the Tafel extrapolation measurements, as seen in Fig. 10a. The following formula is used to determine the C.R.

where M.W. refers to the molecular weight of the corroded material (g/mol), while C.R. denotes the corrosion rate (mpy). Additionally, Icorr represents the current density of corrosion (A cm−2), n indicates the number of charge transfers throughout the corrosion process, and d corresponds to the density (g cm−3)52.

According to the data, the corrosion current density (Icorr.) dropped during the testing period, and the D sample had the lowest corrosion rate (C.R.). As the PKO concentration rose, when compared to a blank sample, the Tafel plot showed a drop in Ecorr., Icorr., and C.R., as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 10a. The study demonstrates that, in comparison to a blank sample, increasing the PKO content results in a drop in Icorr.. On the other hand, PKO increases corrosion resistance in brass alloys. Based on the electrochemical data, the polarization resistance (Rp) values progressively increase with higher concentrations of palm kernel oil (PKO), reflecting improved protection against corrosion53. The blank sample exhibits the lowest Rp value at 0.047 kΩ cm2, while the 7% PKO sample reaches the highest Rp at 3.27 kΩ cm2, indicating a significant enhancement in resistance to corrosion as the inhibitor concentration rises. A similar pattern is seen in the corrosion current density (Icorr.) (µA/cm2), where the blank sample demonstrates a very high Icorr. value of 653 µA/cm2, signaling severe corrosion. However, with the introduction of PKO, the current density significantly decreases, reaching its lowest value at 1.7878 µA/ cm2 with 7% PKO, which clearly indicates that the inhibitor reduces the electrochemical activity on the metal surface, thereby slowing down the corrosion process54,55.

Likewise, the corrosion rate (µm/y) follows a similar trend to that of Icorr.. The blank sample shows the highest corrosion rate at 7559.5 µm/year, but as the concentration of PKO increases, the corrosion rate decreases, reaching 20.696 µm/year at the 7% PKO concentration, demonstrating the effectiveness of PKO in mitigating corrosion55. Regarding the anodic and cathodic slopes (Beta a, Beta c), the anodic slope (Beta a) generally decreases with the increase in PKO concentrations, which suggests that the inhibitor promotes the formation of a more protective passive layer on the metal surface, thereby reducing the anodic dissolution56. Similarly, the cathodic slope (Beta c) shows variations, indicating that the inhibitor suppresses cathodic reactions, likely due to its effect on oxygen reduction or hydrogen evolution. The results validate the effectiveness of the PKO inhibitor in NaCl solution, as evidenced by the shift of Ecorr. toward the y-axis, indicating a significant role of the inhibitor in the cathodic reaction mechanism of the copper alloy, thereby reducing metal dissolution56, as shown in Fig. 10a. In line with other electrochemical measurements, as shown in Figs. 9, 10 and 11 the polarization data reveal that the D sample exhibits the highest corrosion inhibition performance, demonstrating its ability to lower the C.R. of the copper alloy surface through adsorption and/or the formation of a protective film on active sites51.

The open circuit potential (OCP) curves for the blank sample and different palm kernel oil (PKO) concentrations in a 3.5% NaCl solution are displayed in Fig. 10b. This indicates how PKO affects the samples’ electrochemical performance and corrosion behavior. As PKO concentration rises, OCP values shift toward greater negative potentials, which confirms Tafel parameters and plots. By slowing down anodic and cathodic reactions, inhibitors (PKO) improve the metal surface’s protective layer and prevent corrosion at its active sites51. As a result of decreased electron flow associated with corrosion processes, the potential becomes increasingly negative as C.R. decreases54,55. In this regard, using an inhibitor effectively can greatly increase the resistance to corrosion in brass alloys.

Conclusions

The study of the brass crescent has provided valuable insights into its material composition, historical manufacturing techniques, and ongoing conservation challenges. The analysis confirmed that the crescent is a yellow brass alloy (64.77% copper, 33.65% zinc, 1.58% tin), classified as alpha Brass, known for its ductility and corrosion resistance. However, corrosion products such as malachite, atacamite, and chalcopyrite reveal the impact of environmental factors on its degradation, primarily due to electrochemical reactions with pollutants, moisture, and dust. Selective corrosion processes like dezincification were observed, leading to a porous copper-rich structure that compromises the alloy’s integrity. SEM analysis also identified zinc white globules and stress corrosion cracking (SCC), particularly in polluted environments, emphasizing the vulnerability of high-zinc Brass to SCC. Incorporating electrochemical tests, palm kernel oil has been demonstrated to be an effective corrosion inhibitor, with efficiency improving at higher concentrations, as shown by enhanced polarization resistance, lower corrosion current density, and reduced corrosion rates by 99.7%. The gas chromatography analysis of the palm kernel oil confirmed it is rich in fatty acid methyl esters, with lauric acid as the predominant component, aligning with the chemical profile of high-quality commercial oil. This suggests that commercial palm kernel oil is suitable for corrosion inhibition, and laboratory extraction is unnecessary for the current application. These findings highlight the need for targeted conservation strategies to mitigate further corrosion and ensure the long-term stability of the crescent, given its historical and cultural significance.

Data availability

Data availability The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Faltermeier, R. B. A corrosion inhibitor test for copper-based artifacts. Stud. Conserv. 44(2), 121–128 (1999).

Golfomitsou, S. & Merkel, F. Synergistic effects of corrosion inhibitors for copper and copper alloy archaeological artifacts. In Metal 04: Proceeding of the international conference on metal conservation (eds Ashton, J. & Hallam, D.) 344–368 (National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2004).

Rocca, E. & Mirambet, F. Corrosion inhibitors for metallic artifacts: Temporary protection. In Corrosion of metallic heritage artifacts (eds Dillmann, P. et al.) 308–309 (Woodhead Publishing Ltd, England, 2007).

Degrigny, C. The search for new and safe materials for protecting metal objects. In Metals and museums in the mediterranean (ed. Argyropoulos, V.) 308–334 (Tel of Athens, Athens, 2008).

Argyropoulos, V., Boyatzis, S. C., Giannoulaki, M., Guilminot, E. & Zacharopoulou, A. Organic green corrosion inhibitors derived from natural and/or biological sources for conservation of metals cultural heritage. In Microorganisms in the deterioration and preservation of cultural heritage (ed. Joseph, E.) (Springer, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69411-1_15.

Hollner, S., Mirambet, F., Rocca, E. & Reguer, S. Development of new environmentally safe protection systems for the conservation of iron artifacts. In METAL 2010: proceedings of the interim meeting of the ICOM-CC Metal Working Group, Charleston, South Carolina, USA (eds Mardikian, P. et al.) 160–166 (Clemson University, Charleston, 2010).

Kesavan, D., Gopiraman, M. & Sulochana, N. Green Inhibitors for corrosion of metals: A review. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 1, 1–8 (2012).

Abu-Baker, A. N., Macleod, I. D., Sloggett, R. & Taylor, R. A comparative study of salicylaldoxime, cysteine, and benzotriazole as inhibitors for the active chloride-based corrosion of copper and bronze artifacts. Eur. Sci. J. 9, 1857–7881 (2013).

Chellouli, M., Bettach, N., Hajjaji, N., Srhiri, A. & Decaro, P. Application of a formulation based on oil extracted from the seeds of Nigella Sativa L, inhibition of corrosion of iron in 3% NaCl. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 3, 2489–2495 (2014).

Chellouli, M. et al. Corrosion inhibition of iron in acidic solution by a green formulation derived from Nigella sativa L.. Electrochim. Acta 204, 50–59 (2016).

Casaletto, M. P. et al. Inhibition of corten steel corrosion by “green” extracts of Brassica campestris. Corros. Sci. 136, 91–105 (2018).

Benzidia, B. et al. Investigation of green corrosion inhibitor based on Aloe vera (L.) Burm. F. for the protection of bronze B66 in 3% NaCl. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 11, 165–177 (2019).

Begum, A. A. et al. Spilanthesacmella leaves extract for corrosion inhibition in acid medium. Coatings 11, 106 (2021).

Abdel-Karim, A. M. & El-Shamy, A. M. A review on green corrosion inhibitors for protection of archeological metal artifacts. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 8, 35 (2022).

El-Shamy, A. M. & Abdelbar, M. Ionic liquid as water soluble and potential inhibitor for corrosion and microbial corrosion for iron artifacts. Egypt. J. Chem. 64(4), 1867–1876 (2022).

Zouarhi, M. Bibliographical synthesis on the corrosion and protection of archaeological iron by green inhibitors. Electrochem 4, 103–122. https://doi.org/10.3390/electrochem4010010 (2023).

Sheydaei, M. The use of plant extracts as green corrosion inhibitors: A review. Surfaces 7, 380–403. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces7020024 (2024).

Maurya, R., Kumar, S., Pal, S. K., Ji, G. & Rastogi, C. K. Influence of watermelon seed extract on the electrochemical corrosion protection of copper in the saline environment. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 50(3), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.5276/jswtm/iswmaw/503/2024.602 (2024).

Elshahawi, A., Rifai, M. & Abdel Hamid, Z. Corrosion inhibition of bronze alloy by Jatropha extract in neutral media for application on archaeological bronze artifacts. Egypt. J. Chem. 65(SI:13B), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.21608/EJCHEM.2022.149590.6622 (2022).

Radi, M. et al. Performance of Avocado Seeds as new green corrosion inhibitor for 7075–t6 al alloy in a 3.5% NaCl solution: Electrochemical, thermodynamic, surface and theoretical investigations. Port. Electrochim. Acta 41(425–445), 425 (2023).

Rai, S. & Ji, G. Synthesis of mint leaf extract and mint-leaf-based NiO nanoparticles, coating of extract layers without and with NiO nanoparticles on copper through drop-casting, and their analysis for the corrosion prevention in saline water. New J. Chem. 47, 3 (2023).

Pandey, I. & Ji, G. Aqueous extract of pointed gourd seeds for the protection of mild steel corrosion from NaCl. Mater. Today Proc. 103, 272–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.08.309 (2024).

Rai, S. & Ji, G. Corrosion inhibition of copper in NaCl solution by water extract of mint leaves. Mater. Today Proc. 103, 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.10.134 (2024).

Rehioui, M. et al. Corrosion inhibiting effect of a green formulation based on Opuntia Dillenii seed oil for iron in acid rain solution. Heliyon 7, e06674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06674 (2021).

Salleh, N. I. H. & Abdullah, A. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel using palm oil leaves extract. Indones. J. Chem. 19(3), 747–752 (2019).

Bodude, M. A., Nnaji, R. N. Ayoola, W. A. & Adeleke A. B. Evaluation of palm kernel oil as green inhibitor for protection of mild steel in acidic and alkaline media. Contributed Papers from Materials Science and Technology 2019 (MS&T19), Oregon Convention Center, Portland, Oregon, USA (2019). https://doi.org/10.7449/2019/MST_2019_747_754

Oyewole, O., Adeoye, J. B., Udoh, V. C. & Oshin, T. A. Optimization and corrosion inhibition of Palm kernel leaves on mild steel in oil and gas applications. Egypt. J. Pet. 32, 41–46 (2023).

Ellingson, L., Shedlosky, T. J., Bierwage, G. P., de la Rie, E. R. & Brostoff, L. B. The use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy in the evaluation of coatings for outdoor bronze. Stud. Conserv. 49(1), 53–62 (2004).

Cano, E., Lafuente, D. & Bastidas, D. Use of EIS for the evaluation of the protective properties of coatings for metallic cultural heritage: A review. J. Solid State Electrochem. 14(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-009-0902-6 (2009).

Mohamed, W. A., Rifai, M. M., AbdelGhany, N. A. & Elmetwaly, M. S. Testing coating systems for bare and patinated outdoor bronze sculptures. In Metal 2016, Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, New Delhi, India, 26–30 September 2016 (eds Menon, R. et al.) 161–169 (ICOM Committee for Conservation, Paris, 2016).

Barat, B. R., Letardi, P. & Cano, E. An overview of the use of EIS measurements for the assessment of patinas and coatings in the conservation of metallic cultural heritage. In: Chemello, C., Brambilla, L., Joseph, E. (eds.), Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, September 2–6, 2019 Neuchâtel (2019).

Megahed, M. M., Youssif, M. & El-Shamy, A. M. Selective formula as a corrosion inhibitor to protect the surfaces of antiquities made of leather-composite brass alloy. Egypt. J. Chem. 63(12), 5269–5287 (2020).

Sedek, M. Y., Megahed, M. M. & El-Shamy, A. M. Integrating science, culture, and conservation in safeguarding brass antiquities from microbial corrosion. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 10, 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-024-00850-4 (2024).

Yeomans, R. The art and architecture of Islamic Cairo (Garnet Publishing Limited, London, 2006).

Van der Heide, G. J. Brass instrument metal working techniques: the bronze age to the industrial revolution. Hist. Brass Soc. J. 3(1), 122–150 (1991).

Abdelbar, M. & Ahmed, S. Characterization of corrosion mechanism and traditional soldering treatment of a composite bronze lamp from the Greco-Roman period of Egypt. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 16, 149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02037-x (2024).

Scott, D. A. Metallography and microstructure of ancient and historic metals, Getty Conservation Institute in association with Archetype Books (1991).

Vereecke, H. W., Flühmann, B. & Schneider, M. The chemical composition of Brass in Nuremberg trombones of the 16th century. Historic Brass Soc. J. 24, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.2153/0120120011004 (2012).

Ashkenazi, D., Cvikel, D., Stern, A., Klein, S. & Kahanov, Y. Metallurgical characterization of brass objects from the Akko 1 shipwreck, Israel. Mater. Charact. 92, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2014.02.012 (2014).

Scott, D. A. & Schwab, R. Metallography in archaeology and art 153 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Megahed, M. & Abdelbar, M. M. Characterization and treatment study of a handcraft brass trumpet from dhamar museum Yemen. Archeomatica 9(3), 36–41 (2019).

Knotkova, D. & Kreislova, K. Atmospheric corrosion and conservation of copper and bronze. In Environmental deterioration of materials (ed. Moncmanová, A.) 111 (WIT Press, UK, 2007).

Hammouch, H., Dermaj, A., Hajjaji, N., Degrigny, C. & Srhiri, A. Inhibition of the atmospheric corrosion of steel coupons simulating historic and archaeological iron-based objects by cactus seeds extract. In METAL07: proceedings of the ICOM-CC METAL WG interim meeting, Amsterdam (eds Degrigny, C. et al.) 56–63 (Rijskmuseum, Amsterdam, 2007).

Novák, P. Environmental deterioration of metals. In Environmental deterioration of materials (ed. Monc-manová, A.) 47 (WIT Press, UK, 2007).

Scott, A. D. Copper compounds in metals and colorants: oxides and hydroxides. Stud. Conserv. 42(2), 93–100 (1997).

Abdelbar, M. Characterization and conservation study of ancient Egyptian bronze bells. EJARS 11(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejars.2021.210367 (2021).

Scott, A. D. Copper and bronze in Art, Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation (The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, 2002).

Selwyn, L. Metals and corrosion: A handbook for conservation professional 53 (Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, 2004).

Bernardi, E., Bowden, D. J., Brimblecombe, P., Kenneally, H. & Morselli, L. The effect of uric acid on outdoor copper and bronze. Sci. Total Environ. 407(7), 2383–2389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.12.014 (2009).

Daniyan, A. A., Ogundare, O. & AttahDaniel, B. E. Effect of palm oil as corrosion inhibitor on ductile iron and mild steel. Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 12(2), 45–53 (2011).

Ashmawy, A. M., Said, R., Naguib, I. A., Yao, B. & Bedair, M. A. Anticorrosion study for brass alloys in heat exchangers during acid cleaning using novel gemini surfactants based on benzalkonium tetrafluoroborate. ACS Omega 7(21), 17849–17860. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c01119 (2022).

Karunarathne, D. J., Aminifazl, A., Abel, T. E., Quepons, K. L. & Golden, T. D. Corrosion inhibition effect of Pyridine-2-Thiol for brass in an acidic environment. Molecules 27(19), 6550. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196550 (2022).

AbdElRhiem, E. et al. Corrosion suppression and strengthening of the Al-10Zn alloy by adding silica nanorods. Sci. Rep. 14, 15644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64323-x (2024).

Nor, M. S. M. et al. Effects of current density and deposition time on corrosion behaviour of nickel-based alloy coatings. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 14(5), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2022.14.05.025 (2022).

Ding, Q. M., Qin, Y. X., Shen, T. & Gao, Y. N. Effect of alternating stray current density on corrosion behavior of X80 steel under disbonded coating. Int. J. Corros. 2021(1), 8833346. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8833346 (2021).

Zhang, S., Li, Z., Yang, C. & Gou, J. The AC corrosion mechanisms and models: A review. CORROSION 76(2), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.5006/3362 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Conservation Department, Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum, Damietta University, National Research Centre, and Tabbin Institute for Metallurgical Studies for providing the necessary resources to complete this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Open access funding is provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.M. and M.A. conceived, conceptualized, investigated, supervised, and planned the research. M.A., N.A.G., and W.A. conducted the case study analysis and conservation procedures. E.A. and M.A.: investigated; prepared the corrosion tests and wrote the main manuscript text; N.A.G. prepared the coupons and the corrosion inhibitors; and E.A.: methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and performed the electrochemical tests. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Megahed, M.M., AbdElRhiem, E., Atta, W. et al. Investigation and evaluation of the efficiency of palm kernel oil extract for corrosion inhibition of brass artifacts. Sci Rep 15, 4473 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88370-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88370-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The hybrid protection method for copper alloy against electrochemical attack using benzotriazole and Sb₂O₃ nanoparticles synergy

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Structural, Mechanical, and Corrosion Characteristics of Hypereutectic Al-Sb Alloys Synthesized by Powder Metallurgy

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)