Abstract

Steatotic liver disease (SLD) is a common chronic liver disease without effective therapeutic options. Some studies suggest potential health benefits of dietary live microbes. This study aims to investigate the association between dietary live microbes intake and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) / metabolic alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD) / alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in adults. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2018 were analyzed. MASLD was defined according to the latest Delphi Consensus standard. Participants were grouped based on estimated dietary live microbe intake: low (< 104 CFU/g), moderate (104–107 CFU/g), and high (> 107 CFU/g). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to assess the impact of dietary live microbes on MASLD/MetALD/ALD, along with further investigations into non-dietary probiotic/prebiotic relationships. Participants had a weighted mean age of 47.05 years (SE, 0.24) and 50.59% were female. MASLD proportions differ among low (21.76%), moderate (22.24%), and high (18.96%) microbe groups. Similarly, for MetALD, proportions are 7.75%, 6.95%, and 6.44%, and for ALD, 5.42%, 3.59%, and 2.97% in respective groups. The high dietary live microbe intake group was associated with a 16% lower risk of MASLD compared to those in the low intake group (trend test, P = 0.02), while the risk of ALD was reduced by 25% in the moderate intake group. A lack of association was identified between non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic and MASLD/MetALD/ALD. Our study suggests that a relatively high intake of live microbes diets in adults is associated with a lower risk of SLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steatotic liver disease (SLD) is a clinicopathological condition characterized by excessive fat accumulation within hepatocytes, leading to steatosis. The latest Delphi Consensus Statement recommends replacing the term “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” (NAFLD) with “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease” (MASLD) due to the perceived stigmatizing nature of the terms "non-alcoholic" and “fatty”1. Additionally, the daily intake of 30-60 g of alcohol by NAFLD patients can alter the disease’s progression and affect how they respond to treatments. The newly introduced term “metabolic alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD)” aims to offer new perspectives for this patient group, specifically focusing on both metabolic and alcohol-related risk factors1. MASLD stands as the prevailing chronic liver ailment globally, affecting roughly 30% of adults, with its prevalence escalating annually2. It represents a significant contributor to liver-related morbidity and mortality3. In the absence of effective intervention, MASLD may progress to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and ultimately hepatocellular carcinoma, presenting a considerable threat to public health and imposing a substantial disease burden4. Nevertheless, the precise pathogenesis of MASLD remains unclear. Although resmetirom was recently conditionally approved by the US food and drug administration for the treatment of non-cirrhotic metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, effective pharmacological treatments are still under active investigation. Currently, lifestyle interventions are still the mainstay of treatment5. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further investigations into the pathogenesis of MASLD and to pursue the development of effective therapeutic strategies.

Environmental exposures, genetic variants, obesity, poor lifestyle choices (e.g. high-calorie diets, excessive consumption of sugary drinks, physical inactivity, chronic smoking, etc.), and metabolic disorders are established risk factors for NAFLD6. In addition, numerous prior investigations have consistently demonstrated a significant association between gut microbiota dysbiosis and NAFLD development7,8,9,10. The human gut microbiota, characterized by its diverse composition and function, plays a pivotal role in influencing host metabolism, immunity, and overall health11. Dietary and nutritional interventions, such as the consumption of traditional fermented foods, probiotic, or prebiotic, have been shown to effectively modulate the composition and function of gut microbiota7,12. Fermented foods, exemplified by yogurt and kimchi, are crafted by managing microbial growth and catalyzing the transformation of food components through enzymatic action and are enriched with probiotic microorganisms such as lactobacilli13,14. Their probiotic counts and species vary depending on storage conditions, time and processing methods. It is worth noting that many foods, beyond fermented ones, contain live microbes, such as unpeeled fruits like apples, bananas, and peaches, and vegetables like plantain, cassava, and beet greens15. Recent studies indicate that increasing the intake of dietary live microbes promotes health, leading to proposed health strategies that incorporate dietary live microbes as an intervention16,17.

Probiotic refer to a range of live microbes, while prebiotic denote a non-digestible edible substrate, both of which have a beneficial effect on health18,19. Prior investigations have indicated an inverse correlation between high yogurt consumption and NAFLD20,21,22. Additionally, certain studies have explored the independent associations of probiotic and prebiotic intake with NAFLD23,24. However, there is a lack of studies on the relationship between the total dietary live microbes intake and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease / metabolic alcohol-related liver disease / alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

Therefore, the objective of our study is to assess the association of dietary live microbes and non-dietary prebiotic or probiotic intake with MASLD/MetALD/ALD in adults, utilizing cross-sectional data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) spanning from 1999 to 2018.

Materials and methods

Data source

NHANES, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), serves as a comprehensive, multistage research initiative to evaluate the health and nutritional status of a nationally representative cross-section of the population. For this investigation, data from the 1999–2018 NHANES cycles were employed for participant identification. Rigorous procedures and protocols governing NHANES were ethically sanctioned by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, with all participants providing written informed consent. Enhanced Reporting Guidelines were adhered to in the execution of this study25.

Study design and population

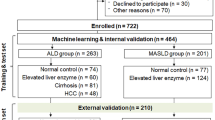

This study utilized data from participants in the NHANES 1999–2018 cycles as the foundation for analysis. Exclusion criteria comprised individuals aged < 20 years, those without laboratory and alcohol consumption data for the calculation of MASLD/MetALD/ALD, those without information on the dietary intake of live microbes intake, and those without demographic details (including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, poverty income ratio [PIR], marital status). Additionally, individuals lacking information on physical activity, smoking status, Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) score, cardiovascular disease (CVD) history, drinks, NHANES cycles, and other relevant data were excluded. After applying these criteria, a total of 18,329 participants were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Definition and estimation of dietary live microbes intake

The dietary live microbe intake data in this study were derived from the estimation of live bacteria quantity (per gram) by four domain experts (MLM, MES, RH, and CH). These experts assessed 9388 food codes from 48 subgroups in the NHANES database15. The estimation process utilized 24-h dietary review data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and was compared with corresponding food codes in the NHANES database, aligned with the food and nutrient database25. Foods were then classified into three categories based on the assessment, representing low (< 104 CFU/g), moderate (104–107 CFU/g), or high (> 107 CFU/g) anticipated levels of live microbes. These categories corresponded to pasteurized foods (< 104 CFU/g), unpeeled fresh fruits and vegetables (104–107 CFU/g), and unpasteurized fermented foods and probiotic supplements (> 107 CFU/g), respectively. The categorization of each type of food has been previously delineated in the extant literature and Table S115.

This study classified participants’ estimated intake of live microbes into three groups based on the grading of various foods. These groups were the low dietary live microbes group (comprising participants who consumed all food live microbes categories graded as low), the moderate dietary live microbes group (comprising participants who consumed foods graded as moderate but not high), and the high dietary live microbes group (comprising participants who consumed foods graded as high). This categorization aligns with previous literature25.

Definition of SLD

SLD is an updated terminology that encompasses the fatty liver disease spectrum, with MASLD being the terminology that specifically replaces NAFLD. This nomenclature shift aims to mitigate stigmatizing language and provide a more clinically relevant classification26.

The diagnosis of SLD follows the United States fatty liver index (US FLI) laboratory criteria, with a diagnostic threshold based on literature, defined as US FLI ≥ 30. The US FLI was calculated based on age, race-ethnicity, waist circumference (WC), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity, fasting insulin, and fasting glucose. At this point, the diagnosis of steatohepatitis is made with a sensitivity of 87% and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.227. When hepatic steatosis is identified via contrast or biopsy, the diagnosis of MASLD is established if the patient exhibits any cardiovascular metabolic risk, and other causes of steatosis can be excluded. Additionally, MetALD is diagnosed in individuals with MASLD who have high alcohol consumption, with thresholds of 20–50 g/day (or 140-350 g/week) for females and 30–60 g/day (or 210-420 g/week) for males. ALD is characterized by steatosis and an average daily alcohol intake of > 50 g (females) / > 60 g (males) in the absence of metabolic risk factors. In other words, a diagnosis of MASLD requires that at least one of the following five conditions be met at the same time as the conditions for a diagnosis of SLD:

a. Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 OR WC > 94 cm (Male) 80 cm (Female) OR ethnicity-adjusted equivalent.

b. Fasting serum glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L [100 mg/dl] OR 2-h post-load glucose levels ≥ 7.8 mmol/L [≥ 140 mg/dl] OR HbA1c ≥ 5.7% [39 mmol/L] OR type 2 diabetes OR treatment for type 2 diabetes.

c. Blood pressure ≥ 130/80 mmHg OR specific antihypertensive drug treatment.

d. Plasma triglycerides ≥ 1.70 mmol/L [150 mg/dl) OR lipid-lowering treatment.

e. Plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) ≤ 1.0 mmol/L [40 mg/dl] (Male) and 1.3 mmol/L [50 mg/dl]) (Female) OR lipid-lowering treatment.

Definition of liver fibrosis

We utilized non-invasive tests, specifically the NFS (non-invasive fibrosis score) and FIB-4 (Fibrosis 4 score), to stratify the risk of liver fibrosis. A NFS score ≤ -1.455 was considered low risk, while a FIB-4 score ≤ 3.25 defined low risk, with scores exceeding these thresholds classified as moderate or high risk. These criteria were used to categorize participants into respective fibrosis risk groups for analysis of the association with dietary live microbe intake.

Covariates

The variables, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, PIR, education level, NHANES cycle, history of CVD, HEI-2015, physical activity, smoking status, and daily drinking, were identified as confounding factors based on previous research and established clinical judgment25,28,29. Daily drinking was specifically defined as the average number of drinks consumed on days when alcohol was ingested in the past 12 months. The drinks were then converted to grams of alcohol (1 drink = 14 g of alcohol) to meet the consensus definition30. Physical activity was characterized as the cumulative self-reported time spent on activities such as walking, biking, home or yard activities, muscular strength exercises, work-related tasks, and recreational activities throughout the week31. Race/ethnicity data were collected through self-reports, and classified into five categories: Mexican American, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, other Hispanic, and others (including multi-racial participants). Educational level was stratified into three groups: less than high school, high school or equivalent, and above high school. Marital status was categorized into four groups: married, never married, living with a partner, and other (e.g., widowed, divorced, or separated). Previous diagnosis of heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, or stroke was recorded as self-reported CVD history. Smoking status was classified into three groups: never smoked (less than 100 cigarettes), ever smoked (smoked more than 100 cigarettes but quit), and current smoker (smoked more than 100 cigarettes and currently smoking)6. The HEI-2015 is a dietary quality index that measures the consistency of diets with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) and consists of 13 dietary components (Table S2)32. The scoring range for HEI-2015 is 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better dietary quality. Selected covariates for laboratory examination include alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

Statistical analysis

The intricate sampling design employed in this study, along with the sample weights for the Mobile Examination Center examination, adhered to the analytical recommendations of NHANES. Baseline characteristics of participants were computed based on the live microbes intake pattern, representing categorical variables as numbers and percentages (%) and continuous variables as means with standard errors (SE). Categorical variables were subjected to chi-square tests with second-order corrections for Rao and Scott; Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous non-normal variables, and t-tests for normal variables to detect differences in characteristics across intake patterns. Additionally, a comparative analysis was performed on the characteristics of both included and excluded participants.

In this study, multivariable logistic regression analysis was utilized to examine the association between estimated live microbes intake patterns (low, moderate, or high) and SLD, and complementary assessment was performed to investigate the association between non-dietary probiotic and prebiotic and SLD. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, PIR, and education level. Model 2 had additional adjustments for CVD history, physical activity, daily drinking, smoking status, HEI-2015, and NHANES cycles based on model 1. Model 3 had additional adjustments for ALT, AST, GGT, and ALP based on model 2. Model 4 was additionally adjusted for HbA1c and triglyceride (TG)/high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) based on model 3. Categorical variables were treated as continuous parameters for linear trend tests.

In subgroup analyses, results were stratified by age (20–40 years, 40–60 years, or ≥ 60 years), sex (female or male), race/ethnicity (Mexican American, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, other Hispanic, or other), educational level (less than high school, high school or equivalent, and above high school), CVD history(no or yes), TG/HDL-c group (Q1, Q2 and Q3), smoking status (never smoked, ever smoked, and currently smoked), drinking status (never drank, ever drank, and currently drank), smoking/drinking status (never drinking or smoking, only drinking or smoking, and drinking and smoking together) and daily alcohol consumption (Male < 30 g/Female < 20 g, Male30-60 g/Female20-50 g, and Male > 60 g/Female > 50 g). To examine the effect of one variable on the outcome based on the level of another variable, a cross-product term was added to the regression model to test for interactions.

We additionally conducted a supplementary analysis examining the relationship between live microbes intake and liver fibrosis, as defined by both the NFS and FIB-4. In the supplementary analyses, due to the live microbes system lacking an evaluation of probiotic/prebiotic supplementation, we carried out an additional assessment of the influence of non-dietary probiotic/prebiotic supplements on MASLD/MetALD/ALD. Consequently, a comprehensive keyword text search was conducted on the names and ingredients of all dietary supplements, along with drug names and ingredients in the NHANES database. This search aimed to identify food categories containing prebiotic, probiotic, and symbiotic. The search term list for identifying prebiotic and probiotic was developed based on prior literature and is detailed in Table S319.

All analyses in this study were conducted using R, version 4.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing), the survey package (version 4–2.1), and Free statistics software (version 1.9.2). Statistical significance was established when two-sided P-values were less than 0.05.

Result

Characteristics of the participants

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population categorized by different levels of dietary intake of live microbes. A total of 18,329 participants were included in our study, with a weighted mean age of 47.05 years (SE, 0.24), of which 9,278 were females (weighted proportion, 50.59%). 6,454 participants were assigned to the low dietary intake group of live microbes, 7,894 participants were in the moderate dietary live microbes intake group, and the remaining 3,981 participants were in the high dietary live microbes intake group. Participants in the high dietary intake group of live microbes were more likely to be female, aged between 40 and 59 years, non-Hispanic white, married, have completed high school or higher education, never smoked, with a high PIR, engage in more physical activity, have high HEI scores, and low alcohol intake (P value < 0.001). In contrast, participants in the low dietary intake group of live microbes had a higher proportion of CVD history and a relatively higher proportion of MASLD and ALD (P value < 0.001).

Figure 2A shows the weighted percentages of MASLD, MetALD, and ALD in different dietary live microbes groups. The proportion of patients with MASLD in different live microbes groups are 21.76% (low), 22.24% (moderate), and 18.96% (high), respectively. The proportion of patients with MetALD is 7.75% (low), 6.95% (moderate), and 6.44% (high), respectively, and the proportion of patients with ALD is 5.42% (low), 3.59% (moderate), and 2.97% (high), respectively. Part B of Fig. 2 shows the metabolic biomarkers of MASLD, MetALD, and ALD (including BMI, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), TG, HDL-C, TG/HDL-C, ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, glucose (GLU), HbA1c, and daily drinking). Overall, except for SBP, the remaining markers showed significant differences between the MASLD, MetALD, and ALD groups. In addition, we used upsets plots to show the overlapping patterns of the five metabolic phenotypes in MASLD. As shown in Fig. 3, the highest number of individuals had all five cardiometabolic risk factors at the same time.

Association between dietary live microbes intake and MASLD/MetALD

The results of the sample-weighted multivariable logistic regression analysis examining the association between dietary intake of live microbes and MASLD/MetALD/ALD are shown in Table 2.

In the crude model, a high dietary intake of live microbes was associated with a lower risk of MASLD compared to the low dietary live microbes group (OR = 0.74, 95%CI, 0.66–0.83), with a statistically significant test of trend (trend test, P < 0.001), while moderate intake of live microbes exhibited no significant association with MASLD risk. After adjusting for age, sex, race, marital status, education level, PIR, CVD history, physical activity, daily drinking, smoking status, HEI-2015, NHANES cycles, ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, HbA1c, and TG/HDL-c (model 4), this relationship remained stable (Trend test, P = 0.02). For MetALD, after adjusting for age, sex, race, marital status, education level, and PIR (model 1), a high dietary intake of live microbes was significantly associated with a lower risk of MetALD (OR = 0.76, 95%CI, 0.61–0.95). However, further adjustments for CVD history, physical activity, daily drinking, smoking status, HEI-2015, and NHANES cycles led to the loss of significance in this relationship. In terms of ALD, in the crude model, both moderate and high dietary intake of live microbes were associated with a lower risk of ALD (Moderate: OR = 0.65, 95%CI, 0.53–0.80; High: OR = 0.53, 95%CI, 0.40–0.72). However, in model 4, only moderate dietary intake of live microbes remained significantly associated with a lower risk of ALD (OR = 0.75, 95%CI, 0.57–0.99), while the high dietary live microbes intake group became no longer significant.

In addition, regression analysis was performed on the association between blood lipids, liver enzymes, blood glucose, body weight, blood pressure, TG/HDL-C, and MASLD/MetALD/ALD (Table S4). Overall, all these metabolic biomarkers were significantly associated with MASLD, MetALD, and ALD (except for ALT). We further presented their dose–response relationships with MASLD and metabolic phenotypes using restricted cubic spline plots (Figure S1). The results showed a non-linear relationship between all markers and MASLD. With the exception of HDL and DBP, there was a non-linear relationship between the remaining markers and MetALD/ALD.

Subgroup analyses and additional analyses

Subgroup analyses exploring the association between dietary intake of live microbes and MASLD/MetALD/ALD in different subgroups are shown in Table S5. No significant interactions were observed in all predefined subgroups (p for interaction > 0.05).

In Table S6, we observed a significant positive correlation between high dietary intake of live microbes and reduced liver fibrosis risk as defined by the NFS score. However, when liver fibrosis was defined using the FIB-4 score, no significant correlation was found between the intake of live microbes and fibrosis risk. These results suggest that the association between live microbial intake and liver fibrosis risk may vary depending on the fibrosis assessment method employed.

Additionally, we assessed the associations between various study parameters (Age, PIR, HEI-2015, PA, BMI, HbA1c, GLU, TG, HDL, SBP, DBP, TG/HDL-C, ALT, AST, ALP, GGT) according to the participants’ smoking and drinking status, and presented the results in the form of a heatmap (Figure S2). The sample-weighted regression analyses presented in Table S7 explored the association between intake of non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic and MASLD/MetALD/ALD. Our study found no significant association between non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic and MASLD/MetALD/ALD.

Discussion

In this extensive national cross-sectional study, we observed that individuals with high dietary intake of live microbes had a lower prevalence of MASLD compared to those with low dietary live microbes intake, while those with moderate dietary live microbes intake were related to a lower risk of ALD. Additionally, there was a lack of association between dietary live microbes intake and MetALD. Our study revealed no significant interactions between dietary live microbes and SLD subgroups. Furthermore, no significant association was observed between non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic intake and SLD.

The gut microbiota dysbiosis interconnects with SLD through the gut-liver axis, a specialized anatomical and physiological structure. Multiple studies demonstrated alterations in gut microbiota composition and abundance in NAFLD patients, covering augmented abundance of genera such as Bacteroides and Prevotella, and diminished abundance of genera such as Ruminococcus and Faecalibacterium33,34. A nationally representative study conducted by Colin Hill et al. substantiated the association between consumption of foods with moderate to high levels of live microbes and favorable blood pressure, anthropometric measurements (BMI, waist circumference), and biomarkers (blood glucose, C-reactive protein, insulin, triglyceride levels, and HDL cholesterol)17, which were inextricably linked with the prevention and improvement of SLD.

The microbial content of food encompasses bacteria, yeast, and molds, which differ based on variables like food category, origin, and manufacturing or processing circumstances. The Western diet is considered to have a low dietary intake of live microbes and has been associated with liver fat deposition and decreased gut microbiota diversity35. In contrast, dietary patterns centered on fruits, vegetables, grains, and legumes are rich in live microbes, exemplified by the Mediterranean diet (MeDdiet). This dietary regimen has demonstrated the ability to foster the reinstatement of gut microbiota diversity and ameliorate the dysbiotic characteristics of NAFLD patients36. However, the specific health benefits of fermented foods remain controversial due to ongoing debate and no consensus. For example, Doreen et al. found that total dairy product consumption and cardiovascular disease risk may have a certain degree of negative correlation, but inconsistent correlations for fermented dairy products (yogurt and cheese)37, underlining that the health advantages of fermented foods may be tied to the specific microbial composition, raw materials, and production methods used. Although this study suggested that dietary intake of high levels of live microbes might decrease the incidence of MASLD, using non-fermented foods (104–107 CFU/g) as a source of conducive microbes may be a superior choice for personal benefits. Particularly noteworthy was that there was no interaction between MASLD and dietary live microbes intake based on current subgroup analysis. However, previous studies indicated that higher levels of education and healthy behavior were associated with healthy dietary patterns (including MeDdiet)38,39, thereby mediating the production of SLD through the same or similar pathophysiological mechanisms as the intake of live microbes. Therefore, more longitudinal research is required to comprehensively comprehend the interactions between individual backgrounds, dietary patterns, and gut microbiota composition to develop personalized prevention and therapy strategies for SLD patients.

Alcohol and metabolic risk factors were known to have a synergistic effect on the overall risk of developing severe liver disease40. The newly coined term MetALD underscored the significance of alcohol’s involvement in fatty liver disease. Both animal and human studies provided evidence supporting a profound correlation between alcohol consumption dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota in the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD)41. Chronic alcohol abuse is associated with compromised intestinal barrier function as a result of perturbations in gut microbiota composition42. Prolonged alcohol consumption has been shown to substantially decrease the abundance of Bacteroides while increasing the levels of Proteus bacteria, consequently leading to impaired intestinal permeability, elevated lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and endotoxins in the liver circulation, and ultimately culminating in liver damage41. These results may imply that augmenting the consumption of live microbes in food could potentially mitigate the detrimental impacts of alcohol on fatty liver by regulating the gut microbiome, but no such effect was revealed in our results. However, the implications of these microbial alterations within the gut remain incompletely elucidated and may be attributed to disease heterogeneity, potential concurrent medication use, as well as variations in patient selection or assessment criteria, resulting in divergent gut microbiota compositions across different populations of SLD subjects under study. Thus, further exploration of the relationship between gut microbiota and SLD necessitates the categorization of patients into distinct subtypes to yield a more comprehensive understanding of their interplay.

Probiotic, particularly lactic acid bacteria, have been extensively documented to ameliorate the advancement of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease via diverse pathways, encompassing the enhancement of gut microbiota dysbiosis, reinforcement of mucosal barrier function, and regulation of the tryptophan pathway43. Nonetheless, in the present investigation, no substantial association was found between non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic consumption and MASLD/MetALD, contradicting previous research findings. This incongruity may stem from the absence of standardization of available probiotic supplements, lack of guidance on optimal formulation or treatment duration, and apparent technical constraints44, resulting in conflicting data within the literature on probiotic. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Tang et al. revealed limited efficacy of probiotic in weight reduction and insufficient evidence to support their effects on liver fat infiltration, blood lipid profiles, liver enzymes, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and glucose homeostasis. Moreover, while the majority of studies have focused on alterations in bacterial composition, differences in fungal and viral composition have also been observed in the gut of SLD patients45,46, contingent on the stage of the disease. This underlines the necessity for circumspection in the interpretation of outcomes from studies on the interaction between probiotic and liver diseases, thus emphasizing the imperative need for further meticulously designed prospective investigations to elucidate these associations.

The liver originates embryonically from the foregut during development and its connection to the gut through the portal vein, ensuring gastrointestinal microbiota-liver connectivity. Insufficient dietary intake of microbes can lead to the mediation of various mechanisms by the gut microbiota in the occurrence and development of SLD. Firstly, an imbalance in the gut microbiota can cause damage to the intestinal barrier function and increased permeability, resulting in elevated absorption of endotoxins and bacterial metabolites by the liver. This process can activate Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors, triggering chronic inflammation and ultimately resulting in the accumulation of hepatic lipids and damage to hepatocytes47. Moreover, disruption of the gut microbiota affects nutrient absorption in the intestine, impacting the body’s energy metabolism and leading to an accumulation of excess fat. Secondly, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can lead to disturbances in bile acid metabolism. The bile acids aid in the emulsification of fats to facilitate lipid absorption, as well as act on the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) to produce antimicrobial peptides that help maintain stability in the intestinal environment. Bile acids also act on the Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) to promote the expression of glucagon-like peptide-1, regulating blood sugar and improving insulin resistance (IR)10. Thirdly, choline plays a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of liver cell membranes and regulating lipid metabolism. The gut microbiota’s influence on the conversion of choline into trimethylamine oxide can induce IR and hepatic steatosis48. Fourthly, the gut microbiota has the capability to generate advantageous short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid via the decomposition of dietary fiber. These SCFAs not only uphold the stability of the intestinal barrier function but also partake in immune regulation and metabolic regulation through the G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway49. Furthermore, some studies proposed that the gut microbiota contributed to the onset and progression of SLD by producing internal alcohol50.

Our findings open up several avenues for future research and application in prevention and personalized nutrition and medicine. Future studies could explore the mechanisms by which dietary live microbes modulate the risk of SLD. Understanding the underlying biological pathways could lead to the development of targeted dietary interventions for at-risk populations. These interventions might include using specific strains of live microbes or combinations that are particularly effective in reducing the risk of SLD. Additionally, public health campaigns could be designed to promote the inclusion of live microbes in the diet as a preventive measure against SLD. Given the variability in individual responses to dietary interventions, personalized nutrition approaches could be employed to tailor the intake of live microbes to individual needs. Genetic predisposition, gut microbiome composition, and metabolic profiles could be used to create personalized dietary plans that optimize the intake of live microbes for each individual. This would ensure that the benefits of live microbes are maximized while minimizing potential risks or adverse effects. The results of our study could inform the development of personalized medical treatments for SLD. By identifying individuals who may benefit most from increased dietary live microbe intake, healthcare providers could offer more precise recommendations for diet and supplementation. Furthermore, the potential for live microbes to be used as therapeutic agents in the treatment of SLD could be explored, with the possibility of developing probiotic-based therapies that target specific aspects of the disease pathophysiology.

This study represents the first investigation exploring the association between dietary live microbes intake and the risk of SLD in a large, representative sample of the US population. The data used in this study are derived from the NHANES, providing a sizable and representative sample size, with rigorous quality control and collection of high-quality clinical variables by trained personnel, ensuring the reliability of the results. However, several limitations in the current study were noted. Firstly, being a cross-sectional study, the observational nature of our investigation prohibits inference of the precise temporal trends and causality between dietary live microbes and SLD, necessitating further prospective RCT research for additional validation. Secondly, the lack of liver histological data in NHANES imposes inherent limitations on the use of the United States Fatty Liver Index (US FLI) as a non-invasive marker for SLD risk, potentially leading to misestimation of the actual disease prevalence of SLD. Nevertheless, a recent cross-sectional study in NHANES demonstrated the reliability of US FLI as a scoring system for diagnosing fatty liver patients51. The ease of implementation and widespread use of this non-invasive technology in epidemiological studies in large populations gives it higher clinical applicability and has gained strong support from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)52. Thirdly, dependence on self-reported dietary intake and alcohol consumption data in NHANES introduces the possibility of recall and social desirability bias, and the use of a simplified universal approach to estimate the microbial quantity in food, defining microbiota levels (< 104, 104–107, and > 107 CFU/g), resulting in numeric imprecision and the lack of an established optimal dosage of dietary probiotic. Furthermore, the current analysis lacks specificity on the total number and types of dietary microbiota. Finally, despite our efforts to control for potential confounding variables, there may still be residual confounders such as stressors, genetic factors, medications, and especially antibiotic use can significantly alter the composition and function of the gut microbiota, which may play an important role in the development of MASLD. Particularly imperative to consider is that SLD encompasses a broad and highly heterogeneous spectrum of diseases, and future research needs to further delineate subtypes of the disease, study individual genetic backgrounds, lifestyles, and the interaction with their respective gut microbiota, and adopt more personalized intervention strategies.

Conclusion

Our study elucidated a significant association between a higher dietary intake of live microbes and a reduced risk of MASLD/ALD. These findings underscore the potential of dietary interventions as a modifiable risk factor for SLD, suggesting a promising avenue for public health strategies aimed at reducing the burden of this condition.

Data availability

The NHANES dataset is publicly available online, accessible at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Abbreviations

- ALD:

-

Alcoholic liver disease

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- GGT:

-

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin, type A1C

- MASLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MetALD:

-

Metabolic alcohol-related liver disease

- NHANES:

-

National health and nutrition examination survey

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- SLD:

-

Steatotic liver disease

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 79(3), e93–e94 (2023).

Chan, W. K. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A state-of-the-art review. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32(3), 197–213 (2023).

van Kleef, L. A. & de Knegt, R. J. The transition from NAFLD to MAFLD: One size still does not fit all-Time for a tailored approach?. Hepatology. 76(5), 1243–1245 (2022).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 136(5), E359–E386 (2015).

Dufour, J. F. et al. Current therapies and new developments in NASH. Gut. 71(10), 2123–2134 (2022).

Wang, X., Seo, Y. A. & Park, S. K. Serum selenium and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in U.S. adults: National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2011–2016. Environ. Res. 197, 111190 (2021).

Chen, J. & Vitetta, L. Gut Microbiota Metabolites in NAFLD Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(15), 5214 (2020).

Ji, Y., Yin, Y., Li, Z. & Zhang, W. Gut microbiota-derived components and metabolites in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Nutrients. 11(8), 1712 (2019).

Jeong, M. K. et al. Food and gut microbiota-derived metabolites in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Foods. 11(17), 2703 (2022).

Lang, S. & Schnabl, B. Microbiota and fatty liver disease-the known, the unknown, and the future. Cell Host Microbe. 28(2), 233–244 (2020).

Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19(1), 55–71 (2021).

Gomaa, E. Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 113(12), 2019–2040 (2020).

Savaiano, D. A. & Hutkins, R. W. Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 79(5), 599–614 (2021).

Dimidi, E., Cox, S. R., Rossi, M. & Whelan, K. Fermented foods: Definitions and characteristics, impact on the gut microbiota and effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. Nutrients. 11(8), 1806 (2019).

Marco, M. L. et al. A classification system for defining and estimating dietary intake of live microbes in US adults and children. J Nutr. 152(7), 1729–1736 (2022).

Roselli, M. et al. Colonization ability and impact on human gut microbiota of foodborne microbes from traditional or probiotic-added fermented foods: A systematic review. Front. Nutr. 8, 689084 (2021).

Hill, C. et al. Positive health outcomes associated with live microbe intake from foods, including fermented foods, assessed using the NHANES database. J. Nutr. 153(4), 1143–1149 (2023).

Gibson, G. R. et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14(8), 491–502 (2017).

O’Connor, L. E. et al. Nonfood prebiotic, probiotic, and synbiotic use has increased in US adults and children from 1999 to 2018. Gastroenterology. 161(2), 476–86.e3 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Association between habitual yogurt consumption and newly diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 74(3), 491–499 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. Probiotic consumption and hepatic steatosis: Results from the NHANES 2011–2016 and Mendelian randomization study. Front. Nutr. 11, 1334935 (2024).

Yuzbashian, E., Fernando, D. N., Pakseresht, M., Eurich, D. T. & Chan, C. B. Dairy product consumption and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 33(8), 1461–1471 (2023).

Famouri, F., Shariat, Z., Hashemipour, M., Keikha, M. & Kelishadi, R. Effects of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 64(3), 413–417 (2017).

Carpi, R. Z. et al. The effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in non-alcoholic fat liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(15), 8805 (2022).

Tang, H., Zhang, X., Luo, N., Huang, J. & Zhu, Y. Association of dietary live microbes and non-dietary prebiotic/probiotic intake with cognitive function in older adults: Evidence from NHANES. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glad175 (2023).

Lee, B. P., Dodge, J. L. & Terrault, N. A. National prevalence estimates for steatotic liver disease and Sub-Classifications using consensus nomenclature. Hepatology. 79(3), 666–673 (2023).

Ruhl, C. E. & Everhart, J. E. Fatty liver indices in the multiethnic United States national health and nutrition examination survey. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 41(1), 65–76 (2015).

Han, L. & Wang, Q. Association of dietary live microbe intake with cardiovascular disease in US Adults: A cross-sectional study of NHANES 2007–2018. Nutrients. 14(22), 4908 (2022).

Tian, T. et al. Dietary quality and relationships with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) among United States adults, results from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients. 14(21), 4505 (2022).

Ciardullo, S. & Perseghin, G. Steatotic liver disease phenotypes in the United States: The impact of alcohol consumption assessment. J. Hepatol. 80(5), e203–e204 (2023).

Paik, J. M. et al. The impact of modifiable risk factors on the long-term outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 51(2), 291–304 (2020).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 118(9), 1591–1602 (2018).

Da Silva, H. E. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and insulin resistance. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 1466 (2018).

Li, F., Ye, J., Shao, C. & Zhong, B. Compositional alterations of gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 20(1), 22 (2021).

Maestri, M., Santopaolo, F., Pompili, M., Gasbarrini, A. & Ponziani, F. R. Gut microbiota modulation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Effects of current treatments and future strategies. Front Nutr. 10, 1110536 (2023).

Calabrese, F. M. et al. A low glycemic index mediterranean diet combined with aerobic physical activity rearranges the gut microbiota signature in NAFLD patients. Nutrients. 14(9), 1773 (2022).

Gille, D., Schmid, A., Walther, B. & Vergères, G. Fermented food and non-communicable chronic diseases: A review. Nutrients. 10(4), 448 (2018).

Mullie, P., Clarys, P., Hulens, M. & Vansant, G. Dietary patterns and socioeconomic position. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64(3), 231–238 (2010).

Fransen, H. P. et al. Associations between lifestyle factors and an unhealthy diet. Eur. J. Public Health. 27(2), 274–278 (2017).

Israelsen, M., Torp, N., Johansen, S., Thiele, M. & Krag, A. MetALD: New opportunities to understand the role of alcohol in steatotic liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8(10), 866–868 (2023).

Sharma, S. P., Suk, K. T. & Kim, D. J. Significance of gut microbiota in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 27(37), 6161–6179 (2021).

Leclercq, S. et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111(42), E4485–E4493 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Emerging trends and hotspots in the links between the gut microbiota and MAFLD from 2002 to 2021: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 990953 (2022).

El Enshasy, H. et al. Anaerobic probiotics: The key microbes for human health. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 156, 397–431 (2016).

Demir, M. et al. The fecal mycobiome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 76(4), 788–799 (2022).

Lanthier N, Delzenne N. Targeting the gut microbiome to treat metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Ready for prime time? Cells. 11(17). (2022)

Safari, Z. & Gérard, P. The links between the gut microbiome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cell Mol. Life Sci. 76(8), 1541–1558 (2019).

Day-Walsh, P. et al. The use of an in-vitro batch fermentation (human colon) model for investigating mechanisms of TMA production from choline, L-carnitine and related precursors by the human gut microbiota. Eur. J. Nutr. 60(7), 3987–3999 (2021).

Rau, M. et al. Fecal SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria in gut microbiome of human NAFLD as a putative link to systemic T-cell activation and advanced disease. United European Gastroenterol. J. 6(10), 1496–1507 (2018).

Yuan, J. et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 30(4), 675–88.e7 (2019).

Sourianarayanane, A. & McCullough, A. J. Accuracy of steatosis and fibrosis NAFLD scores in relation to vibration controlled transient elastography: An NHANES analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 46(7), 101997 (2022).

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis - 2021 update. J Hepatol. 2021;75(3):659–89.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the contribution of all staff and participants in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaohui Zhou and Haoxian Tang has full access to all of the data in this study and assumes responsibility for study supervision. Xiaohui Zhou, Haoxian Tang, Zhikun Dai, and Zihong Bao conceptualized and designed the study. Zhikun Dai, Zihong Bao, Hanyuan Lin, Qinglong Yang, Jintao Huang, Xuan Zhang, Nan Luo acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and drafted the initial manuscript. Xiaohui Zhou, Haoxian Tang, Zhikun Dai, and Zihong Bao reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study protocols of the NHANES were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics institutional review board, with all individuals providing informed written consent. Human study considerations were exempted due to the anonymity of the data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Z., Bao, Z., Lin, H. et al. Effects of dietary live microbes intake on a newly proposed classification system for steatotic liver disease. Sci Rep 15, 5595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88420-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88420-7