Abstract

This study aimed to explore the characteristics of the natural Preferred Retinal Locus (PRL) in eyes with different macular lesions. In this retrospective study, 37 patients (39 eyes) suffered from macular diseases (MD) were included, and the following data were collected: best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), mean sensitivity of macular area in 10 deg diameter (MS), bivariate contour ellipse area (63% BCEA and 95% BCEA), fixation stability, and fundus images and sectional images of the fovea. A natural PRL did not develop in 10 eyes with macular disease. A total of 29 eyes developed natural PRLs: 42% developed superior PRLs, 17% developed temporal PRLs, 24% developed nasal PRLs, 7% developed multiple PRLs, 10% developed PRLs inside the “dark area”, and there were no independent inferior PRLs. In the inside group, the mean MS was significantly lower than that of the other four groups; and the variations in log BCEA were greater in group M compared with group S (P < 0.01), group T (P < 0.01) and group N (P < 0.01), but there were no obvious differences among group S, group T and group N. A natural PRL tends to be more localized in the upper retina, possibly to preserve the lower visual field, followed by nasal and temporal, and rarely localized in the lower retina, and multiple scattered PRLs can be formed when the lesion was widespread. If the function of the fovea exists, even if the lesion in the macular area is clear, the patient still uses the fovea for central fixation and does not form PRL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macular disease (MD) with central scotoma causes remarkable disturbance to the central vision. The scotoma gradually enlarges with the progression of the disease, and the central fixation stability generally decreases, resulting in serious disorders of the fine vision of patients, such as with reading, driving and even face recognition1,2,3,4,5,6. Two decades ago, the majority of patients with bilateral MD would ultimately suffer catastrophic vision loss, until intravitreal anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) drugs7,8,9,10,11,12 and verteporfin with photodynamic therapy13,14 were applied clinically, dramatically relieving the visual outcomes of these patients by preventing the natural process of the diseases. However, until now, the reversal of low vision due to MD has not yet been achieved. Low vision is accompanied by considerable consequences with reference to the psychosocial quality of daily life of MD patients. Fortunately, recent studies have found that it is possible to relocate the central fixation from the damaged fovea to the parafovea where better function remains; called PRL, this eccentric fixation achieves low-vision rehabilitation in patients with MD15,16,17,18.

Normal human adults habitually use fovea-centered fixation, but when the fovea is dysfunctional, people with central vision loss often spontaneously adopt a region outside the fovea as the surrogate fovea for visual tasks, which is considered a natural or original PRL19,20,21. However, this natural PRL is commonly located on the fringe of lesions, and sometimes multiple PRLs develop, which can impact fixation stability and induce a poor vision outcome22,23. Moreover, the location of the PRL is generally uncertain in different cases. Crossland and colleges24 obtained data from several research papers and reported the characteristics of the PRL relative to macular scotomata in a larger low-vision population (1,500 eyes): 37% of PRLs were located below the scotoma, 33% were located on the left, 19% were located on the right, 6% were above the scotoma, less than 2% used a central position (fixating within their scotomata), and 3% had a mixed strategy of multiple PRLs. Superficially, the distribution of PRLs seemed slightly confusing and lacked rules. Therefore, it is necessary to train a preferred PRL by biofeedback training. Morales et al.25 reported a 74-year-old woman diagnosed with adult pseudovitelliform macular degeneration who had developed multiple PRLs naturally; an inferior PRL successfully relocated with relevant visual acuity improvement by 3 months of rehabilitation training. In addition, Scuderi et al.26 reported a 26-year-old woman suffering from Stargardt disease who developed a new PRL with MP-1 microperimetry, and her final best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), mean retinal sensitivity (MS), fixation ability, bivariate contour ellipse area (BCEA), and speed reading were all improved after the training. Furthermore, some larger-sample research has also confirmed that PRLs could be relocated by biofeedback training, whether using luminous flickering stimulus biofeedback or acoustic stimulus biofeedback and any other low-vision aid system, with increased visual function in patients with diverse macular diseases27,28,29,30.

However, the regulation of natural PRLs developing in patients with MD is still being explored. Do all patients with MD possess an opportunity to improve their visual function by training? How can the best location of the PRL be determined for training? How can a proper training program be arranged for different patients with diverse macular diseases? All of these questions continue to confuse researchers. Here, this study aimed to observe the possible prerequisite of development of natural PRLs in patients with MD, as well as the probable causes of different PRL locations occurring in diverse cases. It may provide individual guidance suggestions for the next step of biofeedback training for patients who suffer from different macular diseases.

Methods

Data collection

A retrospective study was conducted in 37 patients (39 eyes) with MD, from May 2018 to December 2019. The inclusion criteria are: The structure of the macular fovea is damaged and scar formed as indicated by OCT, and the MAIA microperimetry examination indicates the formation of an absolute scotoma in the macular center. Eyes that maintained central fixation or fixation losses over 30%, which indicated the unreliability of the test, were excluded. The following data of patients were collected, including age, sex, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and the results of MAIA microperimetry (2013 Edition, Centervue, Padua, Italy), including the following: “average threshold” (the mean sensitivity of macular area in 10 deg diameter, MS); fixation stability, with fixation being stable when 75% of fixations fell inside a 2 deg circle (ST), relatively unstable when 75% of fixations fell inside a 4 deg circle (RS), and unstable when fixation was poorer (US); bivariate contour ellipse area (63% BCEA and 95% BCEA), which measured fixation stability mathematically, and the lower BCEA values define better fixation stability31; and fundus images captured by MAIA and sectional images of the macula captured by Spectralis HRA + OCT (Heidelberg, German). This study was performed according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the Guangzhou Aier Eye Hospital, Guangzhou, China. And written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Procedure of examination

The “4–2 strategy” of the “New Expert Exam” was chosen to perform a complete assessment, which determined macular threshold sensitivity and fixation stability in detail according to the following parameters: stimulus grid of 37 points and 10 deg macular coverage. Regarding fixational target, as a first attempt, the patient was asked whether he or she was able to see the small fixation target (1 deg red circle) located in the center of the MAIA ocular. If he or she could, the MAIA examination was performed; otherwise, an eccentric fixation target (red cross) located outside of the scotoma area or a large fixation target (12 deg red circle) was chosen. Once the patient was able to see the selected eccentric target, the examination could be continued, including the following: fundus perimetry: standard macular test 10 deg; projection field: 30 deg × 30 deg; tracking speed: 25 Hz; stimulus size: Goldmann III; background luminance: 4 asb; stimulus dynamic range: 36 dB; maximum luminance: 1,000 asb; fundus imaging: line scanning laser ophthalmoscopy; field of view: 36 deg × 36 deg; digital camera resolution: 1,024 × 1,024 pixels; optical resolution on the retina: 25 microns; optical source: infrared superluminescent diode at 850 nm; and working distance: 33 mm.

How to record the location of the PRL

The macular area within 10 deg in diameter was divided into four fractions equally: “S” (superior of the fovea), “T” (temporal of the fovea), “I” (inferior of the fovea) and “N” (nasal of the fovea). S represented the area ranging from 45 deg to 135 deg above the central fovea, T represented the area of ranging 135 deg to 225 deg on the temporal side of the fovea, I represented the area ranging from 225 deg to 315 deg below the fovea, and N represented the area ranging from 315 deg to 45 deg on the nasal side of the fovea (Fig. 1A). We determined that the foveal structure was completely damaged through OCT, and determined that the visible lesions on the retina were basically at the same location as the damaged fovea through the fundus photography provided by OCT. Then, the relative position of the natural PRL and the fovea was located through the characteristic retinal vessels. In the microperimetry examination, the instrument can automatically identify the location of the natural PRL and mark it with a blue rhombus32,33.

(A) The schematics of the partition of the macular area 10° in diameter. “S”- superior of fovea, “T”- temporal of fovea, “I”- inferior of fovea, and “N”- nasal of fovea. (B) The location of PRL during the examination was determined using MAIA. The red circle was the fixation target, the purple diamond indicated the initial PRL measured for 10 s at the beginning of examination, and the blue diamond represented the final PRL.

If a natural PRL was found, the specific location and number of the PRL were recorded. The rules of PRL location were that a red circle was the fixation target, normally located on the fovea for individuals with central fixation; a purple diamond indicated the initial PRL, which was measured for 10 s at the beginning of the examination; and a blue diamond represented the final PRL (Fig. 1B). We defined the final PRL as the true PRL for all of the patients.

First, we determined the position of the fovea by comparing the fundus photography captured by MAIA and the section images captured by OCT. Second, two different situations were defined as non-PRL (outside fovea): (1) when the blue diamond exactly overlapped the position of the fovea, we considered that central fixation (fovea fixation) was still maintained; and (2) when the fixation spots (displayed as blue dots) were evenly distributed in the four quadrants, it was inappropriate to determine a possible quadrant of PRL location. Third, if the existence of the PRL was determined, the location of the final PRL was determined according to the relative position between the blue diamond and the fovea. Because in some eyes, the blue dots were not only limited to one quadrant, we defined multiple PRLs when the blue dots were basically equally distributed in two or three quadrants.

The precise location of the PRL was difficult to define in some eyes because of the small scale of the macular lesion and the extremely adjacent PRL. Therefore, we drew two intersection dotted lines that crossed the center of lesions approximately. The four ends of dotted lines were located on the point of vascular cross or other characteristic images as the retinal landmarks on the fundus image without fixation points34. However, this method was based on the assumption that all central scotomas are round, centered on the fovea, and have an eccentric PRL at one of the margins. Then, a circle equally divided into four quadrants of a clockface—upper-left from 9:00 to 12:00, upper-right from 12:00 to 3:00, lower-right from 3:00 to 6:00, and lower-left from 6:00 to 9:00—was superimposed on another fundus image with fixation points. The center of the circle was located on the crossing point of two landmark lines, which marked by a red star.

All of the PRL locations and numbers were determined by two senior doctors. If the results were consistent, the PRL could be located directly. Otherwise, the third senior doctor would finally determine the location of the PRL.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were analyzed using SPSS software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for normality; if the data were normally distributed, they are shown as the means ± standard errors; if not, they are shown as medians. Data were compared among different PRL-location groups and analyzed by ANOVA after Levene’s test, and the LSD test was used for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was of statistical significance.

Results

Eyes with non-PRLs

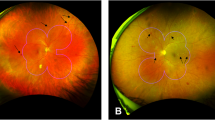

In all 37 patients (39 eyes), natural PRLs did not develop outside the fovea in 10 eyes (Table 1). Furthermore, in 9 eyes of MD1-MD8, the lesions only impacted the parafovea, shown as obvious sensitivity decreases in these areas, but the functional impairment of the fovea was relatively slight, shown as relatively high sensitivity and basically a normal structure of the fovea on OCT images. The BCVA of these eyes was better than 20/200; the ratio of men to women was 6:2; the mean age was 44.8 years old; the mean MS was 21.64 ± 6.38 dB within the macular area (10 deg in diameter); the median value of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 1.1deg2 and 3.2deg2, respectively; and all 9 of these eyes maintained stable fixation (Fig. 2A). However, the left eye of MD9, with severe damage to the fovea showed a lower MS, worse BCVA and a dramatically larger BCEA, indicating unstable fixation. Due to the fixation spots distributed in the four quadrants of the large damaged lesion, we concluded that there had been no PRL that developed (Fig. 2B), and we further checked his duration of blurred vision in this eye until this examination was performed. The case data showed the duration was 2 years at least; thus, we considered that this lesion was an inactive lesion in the fovea, and this patient likely could not develop a PRL spontaneously.

Eyes with non-PRL outside the fovea. (A) MD3, male, 66 years old, the macula was widely damaged, and retinal sensitivity was reduced obviously. Even an absolute dark spot could be seen below the fovea, but the sectional image of the fovea showed that the lesion was nearly above the fovea, not within it. (B) MD9, male, 44 years old, having blurred vision for two years. The macular area was damaged seriously, and a large absolute dark area could be observed in the center of the macular area. The fixation plot captured by MAIA, which showed a mostly even distribution in the four quadrants around the fovea, so it was not possible to determine the precise location of the PRL.

Eyes developing natural PRLs

In 37 patients (39 eyes), a total of 29 eyes developed natural PRLs outside the fovea. Twelve eyes developed superior PRLs (42%), 5 eyes developed temporal PRLs (17%), 7 eyes developed nasal PRLs (24%), and 2 eyes developed multiple PRLs (7%), one of which was located on the nasal and inferior side of fovea, while the other one was located on the temporal and inferior side of the fovea. Three eyes developed PRLs inside the “dark area” (10%), and there were no PRLs located on the inferior of the fovea independently.

Eyes with superior PRLs

In 29 eyes that developed natural PRLs, 12 eyes had superior PRLs, the mean age was 53.42 years old; the mean MS was 20.43 ± 4.42 dB; and the medians of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 2.75deg2 and 8.2deg2, respectively. The BCEA values were checked for normality, and they were not normally distributed; to normalize them, they were log-transformed prior to further analysis, and the log-transformed BCEA was normally distributed. The mean logMAR visual acuity for distance was 1.98 ± 1.14 (Fig. 3; Table 2).

Eyes with temporal PRLs

In 29 eyes developing natural PRLs, 5 eyes had temporal PRLs, the mean age was 45 years old, the mean MS was 22.6 ± 2.86 dB, the medians of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 1.3deg2 and 3.9deg2, respectively; and the mean logMAR visual acuity for distance was 2.46 ± 1.15 (Fig. 4; Table 2).

Eyes with nasal PRLs

In 29 eyes that developed natural PRLs, 7 eyes had nasal PRLs, the mean age was 62.86 years old; the mean MS was 18.09 ± 3.82 dB; the medians of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 2.8deg2 and 8.3deg2, respectively; and the mean logMAR visual acuity for distance was 2.27 ± 0.85 (Fig. 5; Table 2).

Eyes with multiple PRLs or PRLs located inside the dark area

In 29 eyes with natural PRLs, 2 eyes developed multiple PRLs. The mean age was 56.5 years old; the mean MS was 14.00 ± 7.35 dB; the medians of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 21.65deg2 and 64.85deg2, respectively; and the mean logMAR visual acuity for distance was 2.87 ± 0.87 (Fig. 6; Table 2).

Three eyes developed PRLs inside the “dark area”. The mean age was 51 years old, the mean MS was 8.70 ± 3.59 dB, the medians of 63% BCEA and 95% BCEA were 8.5deg2 and 25.3deg2, respectively; and the mean logMAR visual acuity for distance was 1.73 ± 0.59 (Fig. 7; Table 2).

Comparative analysis among groups with different PRL locations

All 29 of the eyes that developed natural PRLs were divided into five groups by differentiating the location of the PRL. S: eyes with superior PRLs; T: eyes with temporal PRLs; N: eyes with nasal PRLs; M: eyes with multiple PRLs; and inside: PRLs located in the “dark area” where the sensitivity map appeared dark on MAIA examination.

-

(1)

The mean MS in the five groups was as follows: in the inside group, the mean MS was significantly lower than that of the groups S (P < 0.01), T (P < 0.01), and N (P < 0.01), and the mean MS of the inside group was lower than that of group M as well, but it was not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Fig. 8A). There was also a significant difference between group T and group M (P < 0.05).

Comparative analysis among groups with different PRL locations. S: eyes with superior PRLs, T: eyes with temporal PRLs, N: eyes with nasal PRLs, M: eyes with multiple PRLs, and inside: PRLs located in the “dark area” where the sensitivity map appeared dark on MAIA examination. (A) The mean sensitivity of macular area in 10 deg diameter (MS) in the five groups, the inside group was statistically lower than that of the groups S (P < 0.01), T (P < 0.01), and N (P < 0.01), and the mean MS was not statistically different between the inside group and group M (P > 0.05). There was also a statistical difference between group T and group M (P < 0.05). (B) The logMAR best corrected visual acuity among five groups, there was no significant difference among these five groups (F = 0.579, P = 0.681) in logMAR visual acuity for distance. (C,D) The variations in log 63% BCEA and log 95% BCEA among five groups, both of them were higher in group M than in group S (P < 0.01), group T (P < 0.01), group N (P < 0.01), and the inside group (P < 0.01). The log 63% BCEA and log 95% BCEA in the inside group were statistically higher than in group S (P < 0.05), group T (P < 0.05), and group N (P < 0.05). **indicates P < 0.01, * P < 0.05.

-

(2)

Regarding visual acuity, there was no significant difference among these five groups (F = 0.579, P = 0.681) in logMAR visual acuity for distance, which indicated that there was no dominant advantage in any group (Fig. 8B).

-

3)

Regarding fixation stability, the variations in log 63% BCEA and log 95% BCEA were consistent with each other perfectly; both of them were higher in group M than in group S (P < 0.01), group T (P < 0.01), group N (P < 0.01), and the inside group (P < 0.01). Moreover, the log 63% BCEA and log 95% BCEA in the inside group were statistically higher than in group S (P < 0.05), group T (P < 0.05), and group N (P < 0.5) (Fig. 8C,D).

Discussion

The trace of cortical reorganization dependent on a natural PRL developing

In this study, a total of 10 of 39 eyes did not develop PRLs naturally, and 29 eyes developed single or multiple natural PRLs. Combined with the fundus images captured by OCT and MAIA, we defined the damage severity of the fovea by distinguishing the extent of distortion of the fovea and the sensitivity map (sensitivity of each stimulus), and the results showed that, as the fovea became an absolute scotoma, or its sensitivity was less than 10 dB, most eyes developed a natural PRL, while PRLs did not develop in two conditions: (1) when the lesion was dispersed with a decrease of MS in the macula, but the OCT showed that the central fovea was in relatively normal shape, and the sensitivity was relatively high (15–25 dB), central fixation would be remain; and (2) when the area of the macular lesion was very large with an obvious reduction in sensitivity (1–5 dB) or even an absolute scotoma (0 dB) had formed, a PRL would not develop spontaneously. Perhaps this large lesion had exceeded the capability that the patient had to locate fixation in the relatively normal retinal area by self-adjusting the oculomotor. Thus, we considered that, when the macula was widely damaged with scattered lesions, but the fovea still had residual function, the foveal fixation would be maintained. This phenomenon might result from the cortical reorganization of visual processing only occurring in conditions of foveal input loss. Baker et al.35 reported large-scale reorganization of visual processing in five individuals with complete loss of foveal input from macular degeneration, while in two other individuals with extensive retinal lesions but some foveal sparing, there was no evidence of reorganization36. Consistently, Dilks et al.37 reported six individuals with complete bilateral loss of central vision who showed visual cortical reorganization, whereas two with bilateral central vision loss but with foveal sparing did not, and in their further research, they confirmed that complete loss of foveal function was a necessary prerequisite for visual cortex reorganization38. In conclusion, patients with widespread and scattered lesions in the macular area but in whom the fovea is still functional, foveal fixation would be maintained, which might be related to a lack of cortical reorganization of visual processing since the foveal input remains.

The two conditions of non-PRL developing

As mentioned above, 10 eyes without natural PRLs were considered with two conditions: condition I: 9 eyes with slight damage to the fovea; and condition II: 1 eye (MD9) with severe damage to the fovea. Our results showed that the overall sensitivity of the macular region, fixation stability and BCVA in the former eyes with slight damage of the fovea were better than those in the severer eye, except for MD7, who had a lower MS compared with MD9, and its temporal parafovea had become absolutely dark, but the OCT showed that the structure of his fovea mostly remained, so the patient still maintained central fixation, and the BCVA was better than 20/200. These results suggested that damage to the fovea was the decisive factor of final visual acuity in eyes with MNV, and a well-functioning fovea contributed to stable fixation; however, the MS might not always be consistent with fixation stability and BCVA. We considered that the most likely reason was that the MS was a mean value of sensitivity in the macular area, but it was not an exact functional reflection of the fovea. In Ratra et al.’s research, they also found that the mean retinal sensitivity improved as the fixation stability improved with reduction in the BCEA after relocating the PRLs of patients with central scotomata by acoustic biofeedback training18. This outcome suggested that the higher that the MS was, the more beneficial that it was for patients to maintain a stable fixation when the foveal function was satisfactory. In contrast, MD9 had serious and widespread damage in the macular area with truly unstable fixation and a dramatically enlarged BCEA, and we concluded that there was no natural PRL developing in this eye. Schonbach et al.39 demonstrated that fixation stability was significantly correlated with visual acuity, but there was a significant difference between shorter and longer measurements, indicating that, with the duration of disease prolonging, the fixation stability of patients would gradually change, and it would take a certain amount of time for the natural PRL to develop. However, according to the case data, MD9 had suffered from MD for 2 years at least, a long duration; thus, we considered that perhaps the large lesion had exceeded his capability, and he located fixation to the relatively normal retinal area by self-adjusting the oculomotor, rather than the cause being the duration of the disease.

The location and function of natural PRLs

In our study, a total of 29 of 39 eyes developed natural PRLs: 12 eyes developed superior PRLs (42%), 5 eyes developed temporal PRLs (17%), 7 eyes developed nasal PRLs (24%), 2 eyes developed multiple PRLs (7%), 3 eyes developed PRLs inside the “dark area” (10%), and there were no PRLs located inferior to the fovea independently. It was interesting that PRLs were located inside the “dark area” in some eyes, and we supposed that there might be some sparking regions outside the fovea that remained functional in the “dark area” so that PRLs spontaneously developed in this region, and we called it the “residual island”. When the severe damage to the macula was widespread and diffuse, while the PRL developed in the “residual island” of the lesion, it seemed to be a non-PRL and still fixated with the fovea. However, the fovea had completely formed an absolute scotoma, so why had the BCVA reached more than 20/200 in our research? It was most likely that the PRL developed in the functional “residual island”. Agreeing with our hypothesis, Sabel et al.40 proposed the “residual vision activation theory” of how visual function could be reactivated and restored. They suggested that there were some residual fields that were “islands” of surviving tissue inside the blind field, and these residual structures could be reactivated by engaging them in repetitive stimulation. Additionally, the natural PRL showed an obvious tendency to locate superior to the fovea, with nearly reached half of the total eyes having a natural PRL. Some researchers have drawn similar conclusions. Ratra et al.18 selected 19 patients with irreversible central scotomata in both eyes and analyzed the locations of their PRLs, and the results showed that the majority (58%) had their PRLs superior to the fovea. Verdina et al.41 investigated morphofunctional features of the PRL and transition zone (TZ) in a series of patients with recessive Stargardt disease, and they observed that the eccentric PRL was often located some distance from the superior edge or border of the area of atrophy.

We further compared the MS and BCVA among the five groups. The results showed that the inside group had the lowest MS, which confirmed that, when the damage was severe and widespread around the fovea, it manifested in dramatically decreased MS and unstable fixation, and it would be difficult for patients to relocate a PRL outside the lesion, so they were prone to developing an inside PRL if there remained a “residual island”. However, the MS was not different among groups S, T and N, which indicated that the MS could not be the determinant of the location of the natural PRL; in other words, natural PRL was not inclined to locate in regions with a high MS. Why was there an advantage of a superior PRL? Cheung and Legge42 hypothesized that function-driven selection of PRL locations might be determined by the nature of the visual tasks. Further, some research has confirmed that PRLs located in the superior retina (inferior visual field) would be better for reading and walking25,42,43. In this research, the visual acuity in the five groups showed no significant differences, indicating that there was no dominant advantage in any group. Furthermore, in the eyes with limited lesions in the fovea and severely damaged foveae (sensitivity generally less than 10 dB), natural PRLs developed and were commonly located at the edge of the lesion with decreased sensitivity, which might have no benefit to the visual function improvement of the patients. Some studies have reported the same finding. Krishnan and Bedell22 determined the retinal sensitivity of fixation PRLs in 29 subjects with bilateral macular disease using the NIDEK MP-1 microperimeter with a standard 10–2 grid (68 locations, 2 degrees apart), and they concluded that the fixation PRL in subjects with bilateral CVL frequently included local regions of sensitivity loss. Bernard and Chung23 used a scanning laser ophthalmoscope to position visual targets at precise retinal locations, and they measured acuity psychophysically for five observers with bilateral macular disease. The results showed that the acuity at the PRL was never the best among all of the testing locations. Instead, acuities were better at 15–86% of the testing locations other than the PRL, with the best acuity 17–58% better than that at the PRL. The locations with better acuities did not cluster around the PRL and did not necessarily lie at the same distance from the fovea or the PRL. Similarly, Denniss et al.45 reported that the location of PRLs varied by approximately 15 degrees horizontally and vertically, and visual field loss was within 5 deg of the PRL in the majority of participants. More than 95% of participants had MS decreases across all of the tested locations and similarly within 1 degree of the PRL, indicating that the location of the PRL was typically at the side of the lesion, where sensitivity had decreased as well. All of these findings implied that the selection of the PRL location was unlikely to be based on high sensitivity and optimizing acuity.

Ultimately, the results of the fixation stability showed that the variations in log 63% BCEA and log 95% BCEA were perfectly consistent with each other; both of them were higher in group M and the inside group compared with group S, group T and group N, but there was no difference among group S, group T and group N. These results indicated that multiple PRLs developing was a signature of worse fixation stability, and if the PRL was located inside of the lesion, the fixation stability would also be unsatisfying; in addition, whenever the PRL was located around the fovea, it might not contribute to the fixation stability in patients with macular lesions. In conclusion, the location of natural PRLs was not dependent on retinal sensitivity, fixation stability or improved visual acuity, which was possibly driven by daily visual tasks. However, in our daily lives, visual tasks are truly complicated and various, so the natural PRL is not the most efficient one for most patients, which is why PRL biofeedback training is necessary for the majority of patients with MD.

The feasible biofeedback training program for different patients

Regarding training schemes for eyes with non-PRLs, when the macula (10° in diameter around the fovea) was widely damaged, and the lesions were scattered, but the fovea still functioned, the majority of the patients would not develop a natural PRL and continued central fixation generally. If the residual function of the fovea could maintain relatively stable fixation, the visual acuity of the patients might be relatively satisfying. For these patients, PRL relocation training should not be performed; only fixation training could be conducted to improve the fixation stability as much as possible. If the fovea is severely damaged and is not sufficient to maintain fixation stability, the visual acuity would be much worse. For these patients, PRL-relocation training is the optimum selection, and it could probably improve the visual acuity greatly after PRL fixation is achieved.

Regarding a training scheme for eyes with natural PRLs, when the lesions in the macula are limited to the fovea, and the function of the fovea is seriously damaged, a PRL would develop spontaneously and be mostly located at the edge of the lesion. If the sensitivity of this natural PRL was sufficiently high to maintain relatively stable fixation, the visual acuity would be relatively satisfying. For these patients, we would not relocate the PRL and only perform fixation training on the original PRL to enhance the fixation stability of these patients. If the sensitivity of the natural PRL was decreased significantly, and it was incapable of maintaining relatively stable fixation, resulting in unsatisfying visual acuity, for these patients, a position with higher sensitivity should be selected around the original PRL for PRL-relocation training, which could possibly improve the visual acuity of patients.

Regarding the training scheme for eyes with inside PRLs, when the macula is widely damaged, and the lesion is diffuse, the fovea is seriously damaged as well; nevertheless, the residual area remains inside the lesion, so the PRL might be located in the “residual island” naturally. If the area of the “residual island” is sufficiently large, it is still possible to maintain relatively stable fixation, while if the area of the lesion is so large that it is not suitable to relocate the PRL outside the lesion, then we must detect the denser sensitivity of the “dark area”, determine the specific location of the “residual island”, and then conduct fixation training to the original PRL for fixation stability improvement. If the area of “residual island” is not sufficiently large, or its function is insufficient, the patient will be unable to maintain stable fixation. For these patients, a higher sensitivity site could be reselected outside the lesion and PRL-relocation training could be provided to improve the visual acuity.

Limitations

Our research has three limitations as follows: (1) the subjectivity of determination of the PRL location; (2) the sample size, which should have been larger, perhaps impacting the credibility of the data analysis; and (3) the location of the fovea, which was determined by the contrast of the fundus images and OCT images, which could only provide rough positioning that was not accurate. Therefore, when the natural PRL and fovea are too close, the natural PRL might be defined as a non-PRL. To minimize the influence of this error, we stopped performing quantitative analysis of the non-PRL and natural PRL groups and only further analyzed the data of eyes with clear locations of PRLs.

Conclusion

A natural PRL tends to be more localized in the upper retina, contributing to their daily visual task performance, followed by nasal and temporal, and rarely localized in the lower retina, and multiple scattered PRLs can be formed when the lesion was widespread. In addition, the location of the natural PRL is typically at the side of the lesion with unsatisfying sensitivity, so a natural PRL is not optimal for patients, thus, it is necessary for the majority of patients who have suffered from MD to undergo PRL-relocation training, which likely will improve the quality of daily life in patients with central vision loss.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Tarita-Nistor, L., Gill, I., González, E. G. & Steinbach, M. J. Fixation stability recording: how long for eyes with central vision loss? Optom. Vis. Sci. 94, 311–316 (2017).

Coco-Martín, M. B. et al. Reading performance improvements in patients with central vision loss without age-related macular degeneration after undergoing personalized rehabilitation training. Curr. Eye Res. 42, 1260–1268 (2017).

Bourne, R. R. A. et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 102, 575–585 (2018).

Mrejen, S. et al. Long-term visual outcomes and causes of vision loss in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 126, 576–588 (2019).

Costela, F. M. et al. People with central vision loss have difficulty watching videos. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 358–364 (2019).

Yu, D. & Chung, S. T. L. Orientation information in encoding facial expressions for people with central vision loss. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 1175–1184 (2019).

Yamashita, M. et al. Intravitreal injection of aflibercept, an anti-VEGF antagonist, down-regulates plasma von Willebrand factor in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 8, 1491 (2018).

Budzinskaya, M. V., Plyukhova, A. A. & Sorokin, P. A. Anti-VEGF therapy resistance in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Vestn Oftalmol. 133, 103–108 (2017).

Pedrosa, A. C. et al. Treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with anti-VEGF agents: predictive factors of long-term visual outcomes. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 4263017 (2017).

Maronas, O. et al. Anti-VEGF treatment and response in age-related macular degeneration: disease susceptibility, pharmacogenetics and pharmacokinetics. Curr. Med. Chem. 27(4), 549–569 (2020).

Kunimoto, D. et al. Evaluation of abicipar pegol (an anti-VEGF darpin therapeutic) in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: studies in Japan and the United States. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina. 50, e10–e22 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Efficacy comparison of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy for three subtypes of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 1425707 (2018).

Sayanagi, K. et al. Time course of swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography findings after photodynamic therapy and aflibercept in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 15, 100485 (2019).

Wei, Q. et al. Combination of bevacizumab and photodynamic therapy vs. bevacizumab monotherapy for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp. Ther. Med. 16, 1187–1194 (2018).

Vingolo, E. M. et al. Visual recovery after primary retinal detachment surgery: biofeedback rehabilitative strategy. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 8092396 (2016).

Vingolo, E. M., Napolitano, G. & Fragiotta, S. Microperimetric biofeedback training: fundamentals, strategies and perspectives. Front. Biosci. (Schol Ed). 10, 48–64 (2018).

Raman, R., Damkondwar, D., Neriyanuri, S. & Sharma, T. Microperimetry biofeedback training in a patient with bilateral myopic macular degeneration with central scotoma. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 63, 534–536 (2015).

Ratra, D. et al. Visual rehabilitation using microperimetric acoustic biofeedback training in individuals with central scotoma. Clin. Exp. Optom. 102, 172–179 (2019).

Plank, T. et al. FMRI with central vision loss: effects of fixation locus and stimulus type. Optom. Vis. Sci. 94, 297–310 (2017).

Cohen, S. Y. & Legargasson, J. F. Adaptation to central scotoma. Part I. eccentric fixations. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 28, 991–998 (2005).

Chung, S. T. The Glenn A. Fry Award Lecture 2012: plasticity of the visual system following central vision loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 90, 520–529 (2013).

Krishnan, A. K. & Bedell, H. E. Functional changes at the preferred retinal locus in subjects with bilateral central vision loss. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 256, 29–37 (2018).

Bernard, J. B. & Chung, S. T. L. Visual acuity is not the best at the preferred retinal locus in people with macular disease. Optom. Vis. Sci. 95, 829–836 (2018).

Crossland, M. & Rubin, G. S. Retinal fixation and microperimetry. In Microperimetry and Multimodal Retinal Imaging, (ed Midena, E.) 5–11. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (2014).

Morales, M. U., Saker, S. & Amoaku, W. M. Bilateral eccentric vision training on pseudovitelliform dystrophy with microperimetry biofeedback. BMJ Case Rep. Jan. 9;2015, bcr2014207969 (2015).

Scuderi, G., Verboschi, F., Domanico, D. & Spadea, L. Fixation improvement through biofeedback rehabilitation in Stargardt disease. Case Rep. Med. 4264829 (2016).

Hassan, S. E., Ross, N. C., Massof, R. W. & Stelmack, J. Changes in the properties of the preferred retinal locus with eccentric viewing training. Optom. Vis. Sci. 96, 79–86 (2019).

Barraza-Bernal, M. J. et al. Can positions in the visual field with high attentional capabilities be good candidates for a new preferred retinal locus? Vis. Res. 140, 1–12 (2017).

Barraza-Bernal, M. J., Rifai, K. & Wahl, S. Transfer of an induced preferred retinal locus of fixation to everyday life visual tasks. J. Vis. 17, 2 (2017).

Calabrese, A. et al. A vision enhancement system to improve face recognition with central vision loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 95, 738–746 (2018).

Li, S., Deng, X. & Zhang, J. An overview of Preferred Retinal Locus and its application in Biofeedback Training for Low-Vision Rehabilitation. Semin Ophthalmol. Feb. 17(2), 142–152 (2022).

Johnson, K. P. et al. Microperimetry and swept-source Optical Coherence Tomography in the Assessment of the Preferred Retinal Locus in a child with Macular Retinoblastoma in the remaining Eye. J. AAPOS. 23, 115–117 (2019).

Crossland, M. D., Engel, S. A. & Legge, G. E. The preferred retinal locus in macular disease: toward a consensus definition. Retina 31, 2109–2114 (2011).

Li, S., Deng, X., Chen, Q., Lin, H. & Zhang, J. Characteristics of Preferred Retinal Locus in eyes with Central Vision loss secondary to different macular lesions. Semin Ophthalmol. 36(8), 734–741 (2021).

Baker, C. I., Peli, E., Knouf, N. & Kanwisher, N. G. Reorganization of visual processing in macular degeneration. J. Neurosci. 25, 614–618 (2005).

Baker, C. I., Dilks, D. D., Peli, E. & Kanwisher, N. Reorganization of visual processing in macular degeneration: replication and clues about the role of foveal loss. Vis. Res. 48, 1910–1919 (2008).

Dilks, D. D., Baker, C. I., Peli, E. & Kanwisher, N. Reorganization of visual processing in macular degeneration is not specific to the preferred retinal locus. J. Neurosci. 29, 2768–2773 (2009).

Dilks, D. D., Julian, J. B., Peli, E. & Kanwisher, N. Reorganization of visual processing in age-related macular degeneration depends on foveal loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 91, e199–e206 (2014).

Schonbach, E. M. et al. Metrics and acquisition modes for fixation stability as a visual function biomarker. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, BIO268–BIO276 (2017).

Sabel, B. A., Henrich-Noack, P., Fedorov, A. & Gall, C. Vision restoration after brain and retina damage: the ‘residual vision activation theory’. Prog Brain Res. 192, 199–262 (2011).

Verdina, T. et al. Multimodal analysis of the preferred retinal location and the transition zone in patients with Stargardt Disease. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 255, 1307–1317 (2017).

Walsh, D. V. & Liu, L. Adaptation to a simulated central scotoma during visual search training. Vis. Res. 96, 75–86 (2014).

Trauzettel-Klosinski, S. Rehabilitative techniques. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 102, 263–278 (2011).

Greenstein, V. C. et al. Preferred retinal locus in macular disease: characteristics and clinical implications. Retina 28, 1234–1240 (2008).

Denniss, J. et al. Properties of visual field defects around the monocular preferred retinal locus in age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, 2652–2658 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shengnan Li made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and the, acquisition, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the data, data statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. She was also involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Jinglin Zhang and Danjie Li made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and the interpretation of the data. They were also involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Huimin Lin and Li Wang made partial contributions to the data acquisition and interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Li, D., Wang, L. et al. The natural preferred retinal locus in patients with macular disease. Sci Rep 15, 25348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88421-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88421-6