Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) constitutes a substantial proportion of cases among the non-obese population, yet it is frequently overlooked. Studies investigating the association between triglyceride-glucose (TyG)-related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHtR) and NAFLD in non-obese individuals is limited. Thus, this study aims to investigate the association between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD in non-obese individuals to improve early detection and intervention strategies for NAFLD in this population. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from the NAFLD database, including 11,987 participants who underwent health examinations between 2004 and 2015. Logistic regression models were employed to evaluate the relationship between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD risk, incorporating cubic spline functions and smooth curve fitting to identify potential nonlinear relationships. ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the predictive performance of thee parameters. After controlling for confounding variables, the incidence of NAFLD in non-obese individuals increased with higher TyG-related parameters. Notably, nonlinear relationships between the TyG index and its related parameters regarding NAFLD risk were identified. The areas under the ROC curve for the TyG index and its related parameters were 0.7984, 0.8553, 0.8584, and 0.8353, respectively. Importantly, the predictive ability of the TyG index and its related parameters was stronger in the female population than in that of males. A positive and nonlinear relationship exists between the TyG-related parameters in relation to the risk of NAFLD. The TyG-related parameters exhibit predictive capabilities for NAFLD, with TyG-related parameters demonstrating greater strength than the TyG index itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver due to non-alcoholic factors, which impairs liver metabolic functions1. NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and can potentially progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma2,3. Worldwide, NAFLD affects over 25% of adults, and in China, the prevalence exceeds 20% among adults4,5,6. NAFLD is closely associated with metabolic syndrome and is linked to cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, polycystic ovary syndrome, and certain cancers7,8,9,10. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial for mitigating its adverse health effects.

Methods for identifying NAFLD primarily include imaging, histology, and serological biomarkers, such as serum insulin levels, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and serum glutamyl transpeptidase. These methods are used alongside evidence of overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes, or metabolic dysregulation11,12. However, the applicability and adoption of imaging studies and liver biopsies may be restricted in some healthcare facilities and regions. Some markers may lack sensitivity and specificity, which can lead to misdiagnoses or missed diagnoses. Therefore, further research is necessary to refine prediction methods, enhance diagnostic accuracy and convenience, and better guide clinical practice and patient management.

NAFLD is closely associated with insulin resistance, which significantly contributes to its development and progression13,14. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, derived from fasting glucose and triglyceride levels, is a reliable indicator of insulin resistance and shows promise in predicting the risk of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD15,16,17. Research indicates a positive correlation between the TyG index and NAFLD, suggesting that individuals with higher TyG indices are at an increased risk of developing NAFLD18. This finding supports the efficacy of the TyG index as a predictive tool for assessing NAFLD risk. Furthermore, ongoing studies are exploring TyG-related parameters, including the TyG index combined with waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR)17,19. This diversified approach may improve the accuracy of NAFLD predictions by considering various metabolic factors.

Obesity is significantly associated with NAFLD, a relationship well documented in numerous studies20,21. However, it is concerning that a substantial proportion of non-obese individuals are also affected by NAFLD. Epidemiological data indicate that the prevalence of NAFLD among non-obese populations ranges from 10 to 30% in both Western and Eastern countries, reaching 17.5% in China22,23. Furthermore, the connection between NAFLD and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in non-obese patients indicates a higher risk, suggesting that these individuals may be more vulnerable to cardiovascular health issues than their obese counterparts24. Despite this, research on NAFLD in non-obese populations remains relatively scarce. According to our understanding, previous studies have found a positive correlation between the TyG index and TyG-BMI with the risk of NAFLD in non-obese individuals in China25,26. However, these studies have not compared the predictive value of the TyG index with TyG-related indices. Considering this, the present study aims to explore the relationship between the TyG index and related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) with NAFLD in non-obese individuals to facilitate early intervention for this population.

Method

Data source

The primary data was obtained from the DATADRYAD database, as disclosed by Okamura et al. (2019)27. The information originates from a study available in the Dryad database named ‘Ectopic fat obesity poses the highest risk for developing type 2 diabetes: An extensive longitudinal study.’ According to Dryad’s terms of use, performing additional analyses on this data by different scientists does not violate the copyrights of the initial creators.

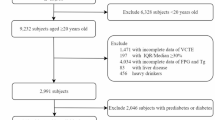

Study population

The NAGALA database from Murakami Memorial Hospital in Japan served as the data source for this cross-sectional study. Participant identifiers were replaced with non-traceable codes, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, receiving approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Murakami Memorial Hospital. Inclusion Criteria: Participants were required to have undergone at least two health check-ups at Murakami Memorial Hospital between 1994 and 2016, and to be aged 18 years or older but under 80 years old. All participants provided informed consent. Exclusion Criteria: Individuals were excluded if they had diabetes, elevated fasting blood glucose levels, known liver conditions, were taking medications, consumed excessive alcohol, or were missing data for abdominal ultrasound, alcohol consumption, or laboratory parameters. Additionally, individuals with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m² were also excluded (see Fig. 1 for the study flowchart). After excluding 9,007 participants, data analysis was performed on 11,987 individuals. The study included variables such as the number of participants, age, height, BMI, WC, WHtR, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), sex, smoking status (non-smoker, ex-smoker, current smoker), drinking status (non-drinker, ex-drinker, current drinker), as well as the TyG index and its related measures (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR).

Data collection

Covariates were selected based on clinical practice and existing literature. The following variables were included as covariates: gender, age, height, BMI, liver function markers, lipid panel, hypertension, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and drinking behavior.

Indices: TyG Index, modified TyG-Related parameters

The TyG index was calculated using the formula: ln [fasting serum TG (mg/dL) × fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)/2]28. TyG-BMI was calculated as [TyG index × BMI]27, TyG-WC as [TyG × WC]19 and TyG-WHtR as [TyG × WC/height]29.

Definition of NAFLD and obesity

Participants were questioned about their weekly alcohol consumption over the previous month, specifying the type and quantity consumed, and then estimating their average weekly ethanol intake. Those included in the study reported minimal or no alcohol intake (below 20 g/day for females and below 30 g/day for males)30. Skilled technicians conducted abdominal ultrasounds, while gastroenterologists, blinded to participants’ personal details, analyzed the ultrasound images for signs of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, including liver-kidney echo contrast, liver brightness, deep attenuation, and vascular blurring. NAFLD, a liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction, was redefined in 2020 as MAFLD31,32. Obesity was characterized by a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m^227.

Statistical analysis

The study included participants categorized into two groups: those with NAFLD and those without NAFLD. Descriptive statistics were provided for continuous variables, reporting means and standard deviations for normally distributed data, and medians for non-normally distributed data. Frequencies and proportions were reported for categorical variables. Group differences were assessed using t-tests, chi-square tests, or Mann-Whitney U tests based on the data distribution. Various logistic regression models were developed to examine the association between the TyG index, its related parameters, and the risk of NAFLD. The models included an unadjusted baseline model (Model I), a model adjusted for gender and age (Model II), and a comprehensive model adjusted for multiple covariates (Model III: age, gender, BMI, WC, WHtR, AST, ALT, GGT, HDL-c, TC, SBP, DBP, smoking status, and alcohol consumption). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each model. Nonlinear relationships were explored using cubic spline functions and smoothing curve fitting. the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the predictive ability of the TyG index, TyG-BMI, BMI-WC, and BMI-WHtR for NAFLD, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) indicates the predictive performance of the model, with larger values representing better performance. An AUC between 0.5 and 0.7 is considered acceptable, 0.7 to 0.9 is regarded as good, and an AUC greater than 0.9 is considered excellent. In this study, we used Youden’s index to select the optimal cut-off value33,34. The analysis was conducted using Empower Stats software and R language, with statistical significance defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05.

Result

Participants’ baseline characteristics

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of participants’ baseline characteristics to explore the relationship between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD risk. A total of 11,987 participants were included, comprising 6,227 females (51.95%) and 5,760 males (48.05%), with an average age of 43.45 ± 8.98 years. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the participants, comparing those with and without NAFLD. Overall, participants with NAFLD were older, with an average age of 45.89 years, compared to 43.18 years in those without NAFLD (P < 0.001). Additionally, BMI, height, WC, and WHtR were significantly higher in the NAFLD group (all P < 0.001). Liver function markers, including ALT, AST, and GGT, were significantly elevated in participants with NAFLD. Similarly, the lipid profiles indicated lower levels of HDL-c and higher levels of TG and TC in the NAFLD group (all P < 0.001). In terms of blood pressure, both SBP and DBP were higher in individuals with NAFLD (P < 0.001). There were also significant differences in gender distribution and lifestyle factors such as smoking and drinking between the two groups (all P < 0.001). Finally, the TyG index and its related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHtR) were significantly higher in participants with NAFLD (all P < 0.001). Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the TyG index and related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHtR), which followed a normal distribution.

Distribution of TyG index, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC and TyG-WHtR. (A) showed that TyG index presented a normal distribution ranging from 5.63 to 10.73, with a mean level of 7.92. (B) indicated that TyG-BMI presented a normal distribution ranging from 97.489 to 200.65, with a median level of 167.42. (C) indicated that TyG-WC presented a normal distribution ranging from 339.45 to 931.05, with a median level of 586.28. (D) indicated that TyG-WHtR presented a normal distribution ranging from 2.10 to 5.49, with a median level of 3.56.

The relationship between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD in different model

Table 2 displays the ORs and 95% CIs associated with various metrics and NAFLD. Our analysis revealed a positive association between the TyG index and its related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) with NAFLD. Initially, we did not adjust for any variables, and we found that the TyG index and its related parameters (TyG-BMI, BMI-WC, and BMI-WHtR) were positively correlated with the incidence of MAFLD, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) as follows: 6.76 (6.02, 7.59) for the TyG index, 1.07 (1.06, 1.07) for TyG-BMI, 1.02 (1.02, 1.02) for BMI-WC, and 15.64 (13.43, 18.22) for BMI-WHtR. After adjusting for age and gender, the positive correlations remained significant with adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of 5.05 (4.46, 5.71) for the TyG index, 1.06 (1.06, 1.06) for TyG-BMI, 1.02 (1.02, 1.02) for BMI-WC, and 12.81 (10.91, 15.05) for BMI-WHtR. Further adjusting for age, gender, BMI, WC, WHtR, AST, ALT, GGT, HDL-c, TC, SBP, DBP, smoking status, and drinking status, we still found that the TyG index and related parameters maintained positive correlations with MAFLD, with ORs and 95% CIs of 2.45 (2.08, 2.89) for the TyG index, 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) for TyG-BMI, 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) for BMI-WC, and 6.40 (4.55, 9.01) for BMI-WHtR.

To delve deeper into the relationship between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD, we categorized the TyG-related parameters into quartiles. For comparative purposes, an OR of 1.00 was assigned to the lowest quartile (Q1) in all models. In each model, the ORs for TyG-related parameters increased with each quartile increment.

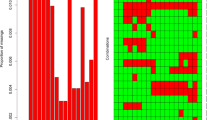

The non‑linear relationship between TyG related parameters and NAFLD

We employed cubic spline functions and smooth curve fitting to investigate the nonlinear relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and the risk of NAFLD (see Fig. 3). We identified a nonlinear relationship between the TyG index and NAFLD risk. Additionally, we identified nonlinear relationships between TyG-related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) and NAFLD risk.

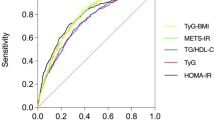

ROC curves for TyG index parameters predicting NAFLD

Figure 4; Table 3 presents ROC curves for TyG index parameters in predicting NAFLD among all participants, males, and females. The AUROC values and 95% CIs for TyG index, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR were 0.7984 (0.7860–0.8107), 0.8553 (0.8454–0.8652), 0.8584 (0.8489–0.8679), and 0.8353 (0.8249–0.8457), respectively (Table 3). In females, the AUROC values were 0.8083 (0.7813–0.8354), 0.8771 (0.8575–0.8966), 0.8767 (0.8576–0.8958), and 0.8578 (0.8373–0.8782). In males, these values were 0.7299 (0.7131–0.7466), 0.7948 (0.7803–0.8093), 0.793 (0.7795–0.8082) and 0.7873 (0.7727–0.8018). The cut-off values for TyG index, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR were 8.19, 181.27, 624.48 and 3.65, respectively.

Discussion

This study reveals a positive and nonlinear relationship between the TyG index and its related parameters and the risk of NAFLD in the Japanese non-obese population. The results indicate that TyG-related parameters (such as TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) have greater predictive capacity for NAFLD than the TyG index itself. This suggests that clinical practice should emphasize monitoring and assessing these parameters. Notably, the predictive ability of the TyG index and its related parameters is stronger in females, emphasizing the importance of gender in NAFLD risk assessment. These findings facilitate the early identification and intervention of individuals at risk for NAFLD, thereby reducing the incidence of the disease and its associated complications.

The TyG index, which is derived from triglyceride and glucose levels, serves as a reliable indicator of insulin sensitivity and has been shown to predict the development of diabetes, prediabetes, and adverse cardiovascular events34,35,36,37. Recent studies have highlighted the significance of TyG-related parameters, particularly TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR. One study found that a higher TyG-BMI significantly increases the risk of prediabetes, particularly in women, non-obese individuals, and those under 50 years of age38. Khamseh et al. demonstrated that TyG-BMI accurately predicts liver fibrosis in non-diabetic overweight or obese individuals39. Another study concluded that TyG-BMI is more effective than the TyG index for assessing NAFLD risk in non-obese patients40. TyG-WC is also utilized to evaluate insulin resistance and predict the risk of MAFLD41. Research indicates that TyG-WC is a more precise marker for predicting MAFLD occurrence, particularly in females. TyG-WHtR is also employed to assess insulin resistance and metabolic health42. Several studies have shown that a higher TyG-WHtR correlates with an increased incidence of fatty liver and is regarded as an effective marker for predicting fatty liver risk19. In summary, although the TyG index and related parameters are closely linked to fatty liver, research examining the relationship between TyG-related indices and NAFLD in non-obese populations remains limited. One study found that TyG-related parameters were more effective than other markers at predicting NAFLD in young, non-obese individuals43. Another study indicated that TyG-WC outperformed HOMA-IR in identifying NAFLD among healthy Korean adults, particularly in non-obese individuals40. In a study conducted on a Chinese population, TyG-BMI proved to be more accurate in assessing NAFLD risk in non-obese individuals compared to individual parameters such as TyG, BMI, TG, and FPG44. However, these studies had relatively small sample sizes, and several merely conducted correlation analyses without ROC curves, failing to incorporate multiple TyG-related parameters simultaneously. Therefore, we analyzed data from a Japanese non-obese population to further explore the relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and NAFLD, addressing the limitations of previous research.

First, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to investigate the relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and NAFLD. After adjusting for confounding variables, we identified significant associations between the TyG index and its related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) with NAFLD, yielding OR of 2.45, 1.04, 1.01, and 6.40, respectively, all with P values < 0.0001. These results align with the findings of most previous studies25,26,45. Additionally, we categorized the TyG-related parameters into four quartiles and observed that the risk of NAFLD increased with ascending quartiles of the TyG index and its associated parameters. We also utilized cubic spline functions, which revealed a non-linear relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and NAFLD risk. Understanding these non-linear relationships can facilitate the development of more personalized screening and prevention strategies. Additionally, we determined that the area under the ROC curve values for TyG-related parameters—TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR—were 0.8553, 0.8584, and 0.8353, respectively; all values surpassed the AU ROC of 0.7984 for the TyG index. These parameters incorporate BMI, WC, and WHtR, reflecting individual fat distribution and body composition. Compared to the TyG index alone, these composite parameters may provide a more accurate assessment of risk, especially for individuals with different body compositions. Furthermore, we found that the cut-off values for TyG-related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR) were 8.19, 181.27, 624.48, and 3.65, respectively. Additionally, the predictive ability of the TyG index and its related parameters was found to be stronger in the female population, which exhibited relatively lower cut-off values. This phenomenon may be attributed that non-obese women tend to accumulate fat in the abdominal and subcutaneous regions, and this pattern of fat distribution may be related to the predictive ability of TyG-related parameters, as abdominal fat is more closely associated with IR and NAFLD46. The results outlined above hold significant guiding value for clinicians in their daily practice, assisting them in accurately identifying high-risk patients at an early stage, thereby enabling appropriate intervention measures. Additionally, we recommend the regular monitoring of TyG-related parameters (TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHtR) during health examinations to facilitate the timely detection of NAFLD risk. We can also establish specific lifestyle intervention plans for high-risk individuals based on the cutoff values of TyG-related parameters (TyG-BMI: 8.19, TyG-WC: 181.27, TyG-WHtR: 624.48, and TyG index: 3.65). These plans may include dietary adjustments, increased physical activity, and the promotion of other healthy lifestyle practices.

This study possesses several strengths. First, it focuses on the non-obese population in Japan, addressing a gap in previous research concerning the relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and NAFLD. Analyzing this specific population enhances the understanding of how metabolic indicators relate to NAFLD risk across various weight statuses and provides clinical guidance for non-obese individuals. Furthermore, we examined not only the TyG index but also systematically assessed related parameters, including TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR. This multidimensional analytical approach allows researchers to comprehensively understand the role of these parameters in predicting NAFLD risk, thus enhancing the reliability and clinical applicability of the results. Finally, this study reveals the non-linear relationship between the TyG index, its related parameters, and NAFLD risk through logistic regression analysis and cubic spline functions. This methodology captures complex biological relationships and provides a scientific basis for developing personalized screening and intervention strategies.

However, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although the participant count is substantial, it is restricted to a Japanese population, which may not accurately represent White or Black groups. Consequently, while our findings may be relevant to Asian populations, they might not apply to White or Black individuals. Secondly, while the participation rate in health examinations is relatively high among the Japanese population, allowing the sample to somewhat represent a larger segment of the population, there remain individuals who do not undergo health check-ups. This may result in certain characteristics of the sample differing from those of the general non-obese population. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of this study does not establish a longitudinal relationship between TyG-related factors and NAFLD incidence in non-obese individuals. This underscores the necessity for further cohort or prospective studies to investigate this specific relationship in greater depth. Furthermore, while TyG-related factors include indicators such as the Fatty Liver Index (FLI), TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, and TyG-WHtR, our study incorporated only three of these factors, which may not fully account for all relevant indicators. Lastly, this study represents a secondary analysis of an existing dataset, which may limit control over all potential variables that could influence the analysis results.

Conclusion

We identified a positive non-linear relationship between the TyG-related parameters, and NAFLD risk. Both the TyG index and its related parameters demonstrate predictive capabilities for NAFLD; however, the TyG-related parameters exhibit superior prognostic abilities, particularly in women. These findings provide a substantial theoretical foundation for future research on the prognosis and treatment of NAFLD and offer valuable insights for medical practice.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Jiménez-Agüero, R. et al. Novel equation to determine the hepatic triglyceride concentration in humans by Mri: Diagnosis and monitoring of Nafld in obese patients before and after bariatric surgery. BMC Med. 12, 137 (2014).

Hwang, S. et al. Interleukin-22 ameliorates neutrophil-driven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through multiple targets. Hepatology 72, 412–429 (2020).

Meoli, L. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and gastric bypass surgery regulate serum and hepatic levels of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2. Am. J. Physiol-endoc M. 315, E613–E621 (2018).

Tan, Y. et al. Perilipin 5 protects against Cellular oxidative stress by enhancing mitochondrial function in Hepg2 cells. Cells-basel 8, (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Systematic review and Meta-analysis of circulating Fetuin-a levels in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Transl Hepato. 9, 3–14 (2021).

Xia, Y. et al. Longitudinal associations between Hand grip Strength and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A prospective cohort study. FRONT. MED-LAUSANNE. 8, 752999 (2021).

Xian, Y. X., Weng, J. P. & Xu, F. Mafld Vs. Nafld: Shared features and potential changes in epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and Pharmacotherapy. Chin. MED. J-PEKING. 134, 8–19 (2020).

Nagatomo, A. et al. A Gedunin-Type Limonoid, 7-Deacetoxy-7-Oxogedunin, from Andiroba (Carapa Guianensis Aublet) reduced intracellular triglyceride content and enhanced autophagy in Hepg2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, (2022).

Li, L. et al. Proteome Dynamics reveals pro-inflammatory remodeling of plasma proteome in a mouse model of Nafld. J. Proteome Res. 15, 3388–3404 (2016).

Seo, D. H. & Kim, S. H. Advanced Liver Fibrosis is Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (Diabetes Metab J ;46:630-9). DIabetes Metab J. 46, 956–957 (2022). (2022).

Song, D. et al. Development and validation of a Nomogram for Prediction of the risk of Mafld in an overweight and obese Population. J. Clin. Transl Hepato. 10, 1027–1033 (2022).

Pittala, S. et al. The Vdac1-Based R-Tf-D-Lp4 Peptide as a Potential Treatment for Diabetes Mellitus. Cells-basel. 9, (2020).

Kucera, O. & Cervinkova, Z. Experimental models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. World J. Gastroentero. 20, 8364–8376 (2014).

Yuan, X. et al. Circular rna expression profiles and features in Nafld mice: A study using rna-Seq Data. J. Transl Med. 18, 476 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is not Associated with Lung Cancer risk: A prospective cohort study in the Uk Biobank. Front. Oncol. 11, 774937 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. The triglyceride and glucose index (tyg) is an effective biomarker to identify nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 16, 15 (2017).

Zhang, R. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose Index and Risk of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease: A Cohort Study. Diabet. Metab. Synd OB. 15, 3167–3179 (2022).

Wang, R., Dai, L., Zhong, Y. & Xie, G. Usefulness of the triglyceride glucose-body Mass Index in evaluating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Insights from a General Population. Lipids Health Dis. 20, 77 (2021).

Xuan, W., Liu, D., Zhong, J., Luo, H. & Zhang, X. Impacts of triglyceride glucose-Waist to height ratio on diabetes incidence: A secondary analysis of a Population-based Longitudinal Data. FRONT. ENDOCRINOL. 13, 949831 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. LncRNA-AK012226 is involved in fat accumulation in db/db mice fatty liver and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease cell model. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 888 (2018).

Mulder, P. et al. Surgical removal of inflamed epididymal white adipose tissue attenuates the development of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 40, 675–684 (2016).

Kim, D. & Kim, W. R. Nonobese fatty liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 474–485 (2017).

Zeng, J. et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, risk factors, and indicators for lean Chinese adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 1792–1804 (2020).

Yoshitaka, H. et al. Nonoverweight nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and incident cardiovascular disease: A post hoc analysis of a cohort study. Med. (Baltimore). 96, e6712 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Association between triglyceride glucose-body mass index and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the non-obese Chinese population with normal blood lipid levels: A secondary analysis based on a prospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 19, 229 (2020).

Ning, Q., Zheng, K., Yan, J. & Zhu, C. Triglyceride glucose index as a predictor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: insights from a longitudinal analysis in non-obese individuals. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 11, 1429413 (2024).

Okamura, T. et al. Ectopic Fat obesity presents the Greatest Risk for Incident Type 2 diabetes: A Population-based longitudinal study. INT. J. Obes. 43, 139–148 (2019).

Lu, Y. W. et al. Gender difference in the Association between Tyg Index and subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the I-Lan Longitudinal Aging Study. CARDIOVASC. DIABETOL. 20, 206 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with Tyg Index and Tyg-related parameters in an Urban Chinese Population: A 15-Year prospective study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 84 (2022).

Anstee, Q. M., McPherson, S. & Day, C. P. How big a problem is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? BMJ-Brit Med. J. 343, d3897 (2011).

Eslam, M. et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 73, 202–209 (2020).

Han, A. L. & Lee, H. K. Comparison of the diagnostic performance of steatosis indices for discrimination of CT-diagnosed metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Metabolites 12, 664 (2022).

Pawluczuk, E., Łukaszewicz-Zając, M., Gryko, M., Kulczyńska-Przybik, A. & Mroczko, B. Serum CXCL8 and its specific receptor (CXCR2) in gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13, 5186 (2021).

van der Staaij, H. et al. Transferrin Saturation/Hepcidin ratio discriminates TMPRSS6-Related Iron Refractory Iron Deficiency Anemia from patients with Multi-causal Iron Deficiency Anemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1917 (2022).

Guerrero-Romero, F. et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the Euglycemic-Hyperinsulinemic Clamp. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 95, 3347–3351 (2010).

Guo, Q. et al. Influence of the triglyceride-glucose index on adverse Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in prediabetic patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 843072 (2022).

Zheng, S. et al. Triglyceride glucose-Waist circumference, a Novel and effective predictor of diabetes in First-Degree relatives of type 2 diabetes Patients: cross-sectional and prospective cohort study. J. Transl Med. 14, 260 (2016).

Song, B. et al. Triglyceride glucose-body Mass Index and Risk of Incident Type 2 diabetes Mellitus in Japanese people with normal glycemic level: A Population-based longitudinal cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 907973 (2022).

Khamseh, M. E. et al. Triglyceride glucose index and related parameters (triglyceride glucose-body Mass Index and triglyceride glucose-Waist circumference) identify nonalcoholic fatty liver and liver fibrosis in individuals with Overweight/Obesity. Metab. Syndr. Relat. D. 19, 167–173 (2021).

Kim, H. S. et al. Triglyceride glucose-Waist circumference is Superior to the Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance in identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in healthy subjects. J. Clin. Med. 11, (2021).

Ju, D. Y. et al. The influence of Waist circumference on insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in apparently healthy Korean adults. CLIN. MOL. HEPATOL. 19, 140–147 (2013).

Kim, A. H., Son, D. H. & Lee, Y. J. Modified triglyceride-glucose index indices are Reliable markers for Predicting Risk of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1308265 (2023).

Song, K. et al. Comparison of the Modified Tyg Indices and Other Parameters to Predict Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Youth. Biology-Basel. 11, (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Triglyceride glucose-body Mass Index is effective in identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese subjects. MEDICINE 96, e7041 (2017).

Zeng, P., Cai, X., Yu, X. & Gong, L. Markers of insulin resistance associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-diabetic population. Sci. Rep. 13, 20470 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Triglyceride glucose-waist circumference: the optimum index to screen nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 376 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023JJ50060) for their financial support, which made this research possible.

Funding

This article was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023JJ50060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiuli Wang, Jie Liu and Ke Yu contributed to the study concept and design, researched, and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. Hanxiong Liu, Xiang Li and Zhenhua Huang analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Liu, J., Yu, K. et al. Association between TyG-related parameters and NAFLD risk in Japanese non-obese population. Sci Rep 15, 7119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88478-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88478-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The mediating effect of triglycerides and related indices on the association between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oral health in adults aged ≥ 45 years from the national health and nutrition examination survey 2003–2016

Lipids in Health and Disease (2026)

-

Evaluation of a new TyG indicator, TyHGB, in predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: evidence from two independent populations

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Association between TyG index and MASLD in lean young adults: a retrospective study

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2025)