Abstract

The high-strength 7xxx Al alloys are frequently used due to their excellent properties. To achieve these properties, heat treatment is crucial. In this study, the influence of La on the microstructure evolution of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys during solution annealing, the first step of heat treatment, was investigated. The results showed that La additions significantly affect the microstructure by increasing in the eutectic solidus temperature, influencing the melting enthalpy of Mg2Si/LaAlSi, promoting the formation of LaAlSi and reducing Mg2Si, increasing the melting enthalpy of α-Al, shortening the time to reach the eutectic melting peak and preventing a significant increase in grain size. A 10 h solution heat treatment was recommended, with minimal benefits after 12 h. 0.15 wt% La was the minimum to prevent an increase in grain size. La altered the Al45Cr7 phase and formed a new Al20Cr2La phase with larger dimensions and sharper edges. Faster cooling rates refine the grain size due to precipitation along the grain boundaries. The content of the T-phase (Mg32(Al, Cu, Zn)49) decreased with increasing annealing time. Prolonged annealing promoted the diffusion of Mg and Zn from the eutectic phases, which led to their dissolution in the matrix. Zn diffused out first, followed by Mg. Prolonged annealing favored the formation of the Al7Cu2Fe phase over the Al13Fe4 phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys have the following advantages: high strength, good wear resistance and low weight, which translates into a good strength–to–weight ratio. This combination makes them very promising for various applications, especially in transportation (cars, planes and trains). Due to their lower weight and better mechanical properties, they are gradually replacing steel or have already replaced it in some cases. However, fatigue strength and resistance to stress corrosion are still limitations for these alloys1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The switch to Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys is crucial for reducing our carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emissions. In the EU, transportation is responsible for 20% of greenhouse gasses, with road transport contributing 72%11,12,13. Cars and vans are responsible for around 15% of CO2 emissions in the EU14. By using lighter materials such as Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys, the automotive and transportation industries can reduce fuel consumption and carbon emissions13,14,15. Compared to steel, Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys are characterized by their lower weight and higher mechanical properties. This impressive combination is achieved through special heat treatments that result in an exceptional strength–to–weight ratio2,4,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. These treatments typically include solution annealing and ageing24,26,27,28,29. In the Al–Zn–Mg–Cu system, the Zn/Mg ratio plays a crucial role in determining the crystalline phases formed and the strength of the alloy. Previous studies2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,17,25,30,31,32,33,34 have identified several phases (in addition to the basic Al crystal structure) that form and solidify during cooling. Importantly, the compositions of these phases, such as M/η (MgZn2)1,3,5,6,9,10,31,32,33,34, S (Al2CuMg)1,2,3,5,6,32,33,34, T (Al2Mg3Zn3, Mg32(Al, Cu, Zn)49 or AlCuMgZn)1,2,3,6,10,31,33,34, V/Z (Mg2Zn11 + Al5Cu6Mg2)3 and σ (T + η/M – Mg(Zn, Cu, Al)2)34, are not fixed. Previous studies6,10,25 have shown that the balance between Zn and Mg (Zn/Mg ratio) plays a key role in the strength mechanism of the alloy. If the Zn/Mg ratio is less than 2.2, the T-phase is the main factor in the strength of the alloy. However, when the ratio is above 2.2, the η/M phase becomes the most important factor for strength. Lim et al.6 analyzed the Zn/Mg ratio in the widely used alloy EN AW-7175 and reported that a lower Cu and Mg content combined with a higher Zn/Mg ratio (3.0) resulted in a lower dissolution temperature (solvus) for the S-phase, resulting in a larger and coarser S-phase. Conversely, a higher Cu and Mg content in combination with a lower Zn/Mg ratio (2.0) resulted in a higher solvus temperature, meaning that the S-phase dissolved more easily during heat treatment.

This study focuses on alloys where the Zn–Mg ratio (Zn/Mg) is between 2.4 and 2.5. The literature indicates that in this range, the η or M-phase (MgZn2) plays a crucial role in strengthening the material6,10,25. The effects of the addition of La on the solidification of the Al-Zn–Mg–Cu alloy (melting point, temperature range during solidification and formation of phases during solidification) have already been investigated35,36. Studies37,38,39,40,41,42 have shown that the addition of La can reduce the size of Al crystals and improve the mechanical properties. Xu et al.37 demonstrated that the addition of La has a refining effect and also reduces the number of precipitates at the grain boundaries. Yuan et al.38 showed that the addition of La significantly refines the grains and improves the tensile properties of the alloy. Meanwhile, Tang et al.39 showed that La additions also affected the SDAS (Secondary Dendrite Arms Spacing), which were reduced. Medvedev et al.40, on the other hand, showed that La additions increased the mechanical strength and thermal stability of the alloy, but decreased its electrical conductivity. In addition to the above results Jiang et al.41 demonstrated that La additions change the phases in the microstructure, in their case this was the Al13Fe4 phase. The main objectives of this work were to investigate how the microstructure evolves during heat treatment (solution annealing) and how the addition of La influences the formation of the different phases. Another crucial question is whether the addition of La influences the microstructure during heat treatment by preventing excessive grain growth. It is expected that the results obtained will open new horizons of knowledge on the influence of La additions on the microstructure and thus the mechanical properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

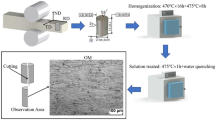

In each experiment, 500 g of the alloy EN AW-7175 (sample A - Table 1) was melted in an electric resistance furnace. The graphite crucible was covered with Ca2O4Si to minimize heat loss and stabilize the molten metal. The melt reached 750 °C and served as the casting temperature for all batches. High purity La (La, 99.99 wt%) was added. To ensure uniform metallurgical parameters, sample A (reference) was also remelted and cast. All samples were cast in a Croning sand cell43 at a cooling rate of 5 °C min− 1. The chemical composition of the alloys was analyzed using an OES ARL iSpark 8860 instrument (Table 1).

An earlier study36 examined the phases present in the as-cast samples at room temperature. Interestingly, the addition of La leads to two new phases: LaAlSi, which replaces the Mg2Si phase, and Al20Cr2La phase, essentially a modified Al45Cr7 phase.

Heat treatment

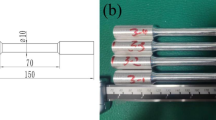

Samples with the dimensions 10 × 10 × 10 mm were prepared for solution annealing. Annealing was performed in an electric resistance tube furnace at 460 °C, with holding times ranging from 1 h to 24 h. After each specified holding time, the samples were rapidly quenched in water. The samples are labeled according to the duration of solution annealing: 0 (0 h), i.e. the sample in the as-cast state, 1 (1 h), 2 (2 h), 3 (4 h), 4 (6 h), 5 (8 h), 6 (10 h), 7 (12 h), 8 (14 h) and 9 (24 h). To avoid confusion, we use a combined naming system for the samples and the corresponding solution annealing times. For example, sample A, which was annealed for 1 h, is labeled “A1” and sample B, which was annealed for 6 h, is labeled “B4”.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

To analyze the characteristic temperatures and melting enthalpies of the samples, the DSC method was used with a NETZSCH DSC 404 F3 Pegasus instrument. The approximately 3 × 3 × 3 mm samples were prepared from the specimens after heat treatment. All samples were run through the same heating program from 25 °C to 720 °C at a heating rate of 10 K min− 1 under an argon (Ar5.0) protective atmosphere, with appropriate corrections made. Empty Al2O3 crucibles were used as reference. The solidus temperatures were determined using the tangent method and the melting enthalpies using the integral surface area calculation.

Microstructure characterization

The remaining material was carefully ground and polished. For SEM analysis, we used a ThermoFisher Scientific Quattro S FEG-SEM (Field Emission Gun Scanning Electron Microscopy) equipped with an Ultim® Max Oxford Instruments EDS (Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy) analyzer. For La-rich phases, a TEM with FEI Tecnai 12 was used to identify and confirm the phase stoichiometry. For TEM samples preparation, focused ion beam (FIB) is used. The grain size was determined according to the ASTM E112 standard using the intercept method.

Results and discussion

DSC

Of the 36 DSC analyzes carried out as part of this study, only a few representative results (heating curves) are shown here (Figs. 1 and 2). Figure 1 shows the DSC heating curve of sample A1 with an enlargement of the Mg2Si melting peak. Figure 2 shows the DSC heating curve for sample C7. The other results are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The melting temperatures of the eutectic phases are in good agreement with the previously published data44 for the Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy.

The temperatures of the eutectic solidus increased with longer solution annealing times (Fig. 3a). Sample A showed a clear temperature jump after 6 h, rising from 479.7 °C to 488.5 °C (8 h), before reaching a plateau after 14 h and finally rising slightly to 492.4 °C after 24 h. Samples B, C, and D all showed an initial increase in temperature after 4 h (from ~ 479 °C to ~ 489 °C), with sample B deviating from this trend after 24 h. However, samples C and D then maintain similar eutectic solidus temperatures, while sample B deviates after 4 h. Figure 3b shows no clear trend for the solidus temperatures of Mg2Si and LaAlSi (due to the low Si content). All samples showed an initial temperature increase up to 14 h, followed by a plateau. The α-Al solidus temperatures (Fig. 3c) decreased with increasing annealing time. La significantly influenced these temperatures, with sample D showing the largest deviation from the reference (sample A). The difference was 12.4 °C after 2 h, which persisted up to 10 h after annealing. After 24 h, samples A and D had similar temperatures, while B and C increased again. After 24 h, samples A, B and D reach comparable temperatures of approximately 561 °C, with C lagging behind at 556.5 °C (although the difference is small). It is worth noting that, the values of A and D (585.8 °C and 586.7 °C) are closer to those of B and C (580.6 °C and 581.0 °C).

Figure 4a shows that the eutectic melt enthalpies decrease for all samples with longer solution annealing times. Sample A decreases from -3.2 J/g to -1.0 J/g, sample B from -2.2 J/g to -1.0 J/g, sample C from -2.9 J/g to -0.8 J/g, and sample D from -3.3 J/g to -1.8 J/g, indicating a minimal influence of La addition. Figure 4b shows low melting enthalpies for the Mg2Si/LaAlSi phase, indicating minimal presence of these phases (below -0.7 J/g). La triggers the formation of LaAlSi, as can be seen in samples B, C, and D after 1 h. Sample D shows the largest difference with a decrease (0.43 J/g) compared to sample A. These deviations are mainly due to the different phase compositions: sample A consists of Mg2Si, sample B consists of a mixture of Mg2Si and LaAlSi, and samples C and D consist of LaAlSi. Figure 4c shows that the α-Al melting enthalpies increase with longer solution annealing times, with a peak at 14 h. Sample A shows the largest jump, increasing from -196.3 J/g to -294.8 J/g after 4 h. Similar increases are observed for samples B (from -211.1 J/g to -292.3 J/g), C (-211.9 J/g to -336.1 J/g), and D (-233.9 J/g to -339.2 J/g). The gap between the α-Al melting enthalpies increases significantly between 4 h and 6 h annealing time. The La content influences the melting enthalpies, with a higher La content leading to higher enthalpies.

Figure 5 shows the development of the eutectic melting peaks for samples A and B with increasing solution annealing time. Sample A (Fig. 5a) initially showed a single peak, which split into two distinct peaks after annealing for 1 h. The splitting gradually decreased and disappeared completely after 10 h. After 12 h the eutectic is almost completely dissolved. Sample B (Fig. 5b) showed a similar pattern, but with one crucial difference: the two melting peaks merged back into one after 6 h. This finding indicates that the addition of La accelerated the return to a single melting peak compared to sample A and significantly shortened the required time (2 h).

Figure 6 confirms the trend observed in Fig. 5 and shows the eutectic melting peaks of samples C and D at the same annealing times. Both Fig. 6a and b show a similar pattern to samples A and B: the double eutectic melting peak disappears after 6 h. This agreement shows that although the addition of La shortens the time for the eutectic melting peak, the amount of La does not affect this time frame.

DSC analyzes of rapidly cooled samples A and C (Fig. 7) confirmed the absence of a eutectic peak in the heating curve. The samples were cast in a Cu mold with a cooling rate of 10–15 °C s− 1, comparable to industrial direct-chill casting45,46. This indicates that the solution heat treatment temperature for Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys can possibly be increased to 470–480 °C19,21,40,47,48,49.

Microstructure evolution

The grain size (Table 2) is the calculated average of 410 grain boundary intersections (ASTM E112 – intercept method). The results of samples 0, 5, 7, and 9 (corresponding to solution annealing times of 0 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h, respectively) show a clear trend towards increasing grain size with longer annealing times. However, the addition of La appeared to suppress grain growth compared to reference sample A (without La). While La did not refine the grain size of the as-cast samples36, it showed a stabilizing effect during solution annealing. The grain size of sample D (with 0.15 wt% La) remained relatively stable between 8 h and 24 h, increasing by only 1.9 μm. This suggests that 0.15 wt% La may be the minimum required for stable grain size during solution annealing.

The EDS analysis of sample A1 (Fig. 8) revealed eutectic phases. Spectra 1 and 2 (brighter) represent the T-phase (Mg32(Al, Cu, Zn)49) indicating a higher Zn content, while spectra 3 and 4 (darker) represent the S-phase (Al2CuMg), with a higher Cu concentration. Part of the Zn remains dissolved, but longer annealing times promote its diffusion from the S-phase. In the as-cast state, the microstructure consists of an α(Al) and a σ[Mg(Zn, Cu, Al)2] eutectic phase36. These phases start to transform into the S-phase and the T-phase during annealing, which is consistent with the DSC results. After annealing for 12 h, only a small part of the eutectic phase remains undissolved. Spectrum 5 corresponds to the Al13Fe4 phase. Although some Cu has dissolved in this phase, this is not sufficient to form the Al7Cu2Fe phase, as the Cu content should be higher than the Fe content50. With longer annealing times (as in samples A6 and A9), the amount of dissolved Cu increases. Spectrum 6 identifies the Mg2Si phase, which is obvious due to the locally increased Mg and Si content. Spectrum 7 shows the chemical composition of the matrix. The matrix already has an increased Zn content, which increases further with longer annealing times.

Figure 9a shows the chemical EDS analysis for the Al45Cr7 phase. Spectrum 8 identifies the AlCr phase, but other alloying elements are also present as the EDS analysis recognizes the surrounding matrix material. Spectrum 9 corresponds to an AlTiB nucleus, probably originating from scrap used in the production of EN AW-7175. Figure 9b shows the EDS elemental mapping, which reveals an increased concentration of Cr compared to the surrounding matrix. There is also an enrichment of Mn and evidence of the Mg2Si phase. The higher concentration of Cu in these regions indicates the presence of the S-phase (Al2CuMg) along the edges of the Al45Cr7 phase. The Al45Cr7 phase was previously identified in a study with a focus on the solidification and microstructure of as-cast alloys36. This identification is based on observations in the literature51,52,53. However, the analysis of this phase goes beyond the current framework, as La additions appear to influence its behavior, as shown in samples B and D.

Figure 10 shows the EDS mapping for an enlarged eutectic phase in sample A6. It is noteworthy that the T-phase is almost absent, as indicated by the lack of a significant Zn enrichment. Localized regions of the increased Cu content correspond to the S-phase. Conversely, Mg appears to diffuse into the matrix when the Fe content starts to increase, which is more evident in sample A9 (Fig. 11). In addition, localized areas with increasing Si and Mg concentrations confirm the presence of the Mg2Si phase.

Figure 11 shows the results of the EDS mapping for sample A9. The image shows that Mg and Zn have diffused out of the eutectic phases and are now distributed in the matrix. In contrast, the concentrations of Fe and Cu, whose diffusion rate in the Al matrix is significantly slower than Mg and Zn, are increased. This prolonged annealing time (24 h) favored the formation of the Al7Cu2Fe phase, which is also consistent with the CALPHAD calculations from the earlier study36. Moreover, the Mg2Si phase partly remains, while the remaining Mg seems to have dissolved in the matrix. We expect a similar trend for the phases in samples B, C and D. The analysis will now continue with samples B and D.

In sample B1 (Fig. 12), the eutectic phases behave similarly to sample A, which is confirmed by the DSC results (Fig. 5). The T-phase (Mg32(Al, Cu, Zn)49) decreases with increasing annealing time, while the S-phase (Al2CuMg) is still present in small quantities after 12 h. Prolonged annealing promotes the diffusion of Mg and Zn from the eutectic phases, which leads to their dissolution in the matrix. Figure 12 also shows the presence of the Mg2Si phase and the Al20Cr2La phase, which is sharp-edged. These tendencies in the eutectic phases are the same in all the samples studied. However, since the behavior of the eutectic phases has already been discussed, the SEM analysis in the following figures (Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15) now focuses on the La-based phases.

Figure 13 shows the results for sample B6. The Al13Fe4 phase (needle-like phase) and the Mg2Si phase are still present. In the La-rich phases, only Al20Cr2La is still present, whereby the annealing time has no significant influence. The LaAlSi phase changes with longer annealing times, as more Cu dissolves in it. Cu diffuses from the eutectic phase into the Al-Fe phase and forms the Al7Cu2Fe phase. Some of the Cu also diffuse into the LaAlSi phase and slowly replaces the Al, as shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14 shows that the T-phase is no longer present, only the S-phase. The acicular LaAlSi phase transforms into the LaCuSi phase as the Al content decreases. This transformation takes place after annealing for 10 h, whereby LaCuSi becomes more stable.

Figure 15 shows two La-rich phases. The eutectic phase remains unchanged, which is consistent with previous trends. The sharp-edged Al20Cr2La phase also remains unchanged, even with longer annealing times. However, the LaAlSi phase loses its Al content with increasing Cu concentration. This trend is consistent with sample B.

A TEM analysis was performed to confirm the stoichiometry of the La-rich phases (Figs. 16 and 17). Figure 16 shows the analysis of sample D1, where the Al20Cr2La phase was identified and confirmed. The crystallographic parameters of the Al20Cr2La phase have already been determined by M. J. Kangas et al.54. Figure 17 shows the analysis of the same sample, but with the LaAlSi phase identified. The latter phase is a ternary compound (the so-called “τ” phase) whose crystallographic parameters were determined by J. Du et al.55.

Conclusions

Based on the results, some main conclusions can be drawn as below:

La addition:

-

La accelerates the temperature rise of eutectic solidus by 2 h (compared to 6 h – reference sample).

-

La promotes the formation of LaAlSi, which leads to the disappearance of Mg2Si and influences its melting enthalpy.

-

A higher La content increases the α-Al melting enthalpy and the sample spacing during the 4–6 h annealing.

-

10 h is the recommended minimum for solution annealing; an extension beyond 12 h offers no significant advantage.

-

0.15 wt% La is the minimum addition required to prevent significant grain growth during solution annealing.

Microstructure evolution:

-

La promotes the formation of LaAlSi (needle-like morphology) at the expense of Mg2Si, which disappears with increasing La content (almost completely in sample D).

-

La also modifies Al45Cr7 and forms larger, sharp-edged Al20Cr2La. Faster cooling reduces the size of these new phases and can refine the grain size due to their precipitation along the grain boundaries.

Phase evolution during solution annealing:

-

As the annealing time increases, the content of the T-phase (Mg32(Al, Cu, Zn)49) decreases, so that after 12 h only a small amount of the S-phase (Al2CuMg) remains.

-

Prolonged annealing promotes the diffusion of Mg and Zn (first Zn, then Mg) from the eutectic phases into the matrix, while the Fe and Cu concentrations increase.

-

Annealing for 24 h favors the formation of Al7Cu2Fe and replaces Al13Fe4.

-

Prolonged annealing reduces Al to LaAlSi and increases Cu; after 10 h LaAlSi disappears and is replaced by LaCuSi.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Tilen Balaško.

References

Azarniya, A., Taheri, A. K. & Taheri, K. K. Recent advances in ageing of 7xxx series aluminum alloys: A physical metallurgy perspective. J. Alloys Compd. 781, 945–983 (2019).

Jia, P. et al. Studies on the microstructures and properties in phase transformation of homogenized 7050 alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 612, 335–342 (2014).

Priya, P., Johnson, D. R. & Krane, M. J. M. Precipitation during cooling of 7XXX aluminum alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 139, 273–284 (2017).

Rometsch, P. A., Zhang, Y. & Knight, S. Heat treatment of 7xxx series aluminium alloys - some recent developments. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China (English Ed. 24, 2003–2017 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Milkereit, B., Kessler, O., Schick, C. & Rometsch, P. A. Development of continuous cooling precipitation diagrams for aluminium alloys AA7150 and AA7020. J. Alloys Compd. 584, 581–589 (2014).

Lim, S. T., Eun, I. S. & Nam, S. W. Control of equilibrium phases (M,T,S) in the modified aluminum alloy 7175 for thick forging applications. Mater. Trans. 44, 181–187 (2003).

Ghiaasiaan, R., Zeng, X. & Shankar, S. Controlled diffusion solidification (CDS) of Al3Zn3Mg3Cu (7050): Microstructure, heat treatment and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 594, 260–277 (2014).

He, K. Z., Tan, Z. M., Zheng, X., Zhang, X. M. & Zhou, K. C. Microstructure and mechanical properties of DC Cast 7065 aluminum alloy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. (2021). (1906).

Colin, M. & Jolliffe, R. Strengthening of 7175 Aluminum Alloy Through Multi-Step Aging Process. 26 (2021).

Österreicher, J. A. et al. Stabilization of 7xxx aluminium alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 740, 167–173 (2018).

Ajanovic, A. & Haas, R. The impact of energy policies in scenarios on GHG emission reduction in passenger car mobility in the EU-15. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 68, 1088–1096 (2017).

Lodi, C. et al. Reducing CO 2 emissions of conventional fuel cars by vehicle photovoltaic roofs. Transp. Res. Part. D Transp. Environ. 59, 313–324 (2018).

Fontaras, G. & Dilara, P. The evolution of European passenger car characteristics 2000–2010 and its effects on real-world CO 2 emissions and CO 2 reduction policy. Energy Policy. 49, 719–730 (2012).

Tsiakmakis, S., Fontaras, G., Ciuffo, B. & Samaras, Z. A simulation-based methodology for quantifying European passenger car fleet CO2 emissions. Appl. Energy. 199, 447–465 (2017).

Hottle, T., Caffrey, C., McDonald, J. & Dodder, R. Critical factors affecting life cycle assessments of material choice for vehicle mass reduction. Transp. Res. Part. D Transp. Environ. 56, 241–257 (2017).

Starink, M. J. & Wang, S. C. A model for the yield strength of overaged Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys. Acta Mater. 51, 5131–5150 (2003).

Deschamps, A. & Bréchet, Y. Influence of quench and heating rates on the ageing response of an Al-Zn-Mg-(Zr) alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 251, 200–207 (1998).

Berg, L. et al. GP-zones in Al–Zn–Mg alloys and their role in artificial aging. Acta Mater. 49, 3443–3451 (2001).

Lin, Y. C., Zhang, J. L., Liu, G. & Liang, Y. J. Effects of pre-treatments on aging precipitates and corrosion resistance of a creep-aged Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy. Mater. Des. 83, 866–875 (2015).

Liu, Y., Liang, S. & Jiang, D. Influence of repetitious non-isothermal aging on microstructure and strength of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 689, 632–640 (2016).

Liu, M., Klobes, B. & Maier, K. On the age-hardening of an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy: A vacancy perspective. Scr. Mater. 64, 21–24 (2011).

Huang, R. et al. Effects of mg contents on microstructures and second phases of as-cast Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 2105–2117 (2022).

Williams, J. C. & Starke, E. A. Progress in structural materials for aerospace systems. Acta Mater. 51, 5775–5799 (2003).

Hou, S., Zhang, D., Ding, Q., Zhang, J. & Zhuang, L. Solute clustering and precipitation of Al-5.1Mg-0.15Cu-xZn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 759, 465–478 (2019).

Suh, D. W., Lee, S. Y., Lee, K. H., Lim, S. K. & Oh, K. H. Microstructural evolution of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu-(Sc) alloy during hot extrusion and heat treatments. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 155–156, 1330–1336 (2004).

Qu, L. et al. Influence of aging treatment on the microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of Al-Zn-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy. Vacuum 200, 110995 (2022).

Kaufman, J. G. Introduction to Aluminium Alloys and Tempers (ASM International, 2000).

Paulisch, M. C., Treff, A., Driehorst, I. & Reimers, W. The influence of natural aging and repeated solution annealing on microstructure and mechanical properties of hot extruded alloys Al 7020 and Al 7175. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 709, 203–213 (2018).

Song, R. & Zhang, Q. Heat treatment optimization for 7175 aluminum alloy by evolutionary algorithm. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 17, 139–141 (2001).

LIU, T. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of squeeze-cast Al – 5.0Mg – 3.0Zn – 1.0Cu alloys in solution-treated and aged conditions. . Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China (English Ed.) 30, 2326–2338 (2020).

Subroto, T. et al. Semi-solid constitutive parameters and failure behavior of a cast AA7050 Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 52, 871–888 (2021).

Wolverton, C. Crystal structure and stability of complex precipitate phases in Al–Cu–Mg–(Si) and Al–Zn–Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 49, 3129–3142 (2001).

Li, C., Chen, Z., Zeng, S., Cheng, N. & Chen, T. Intermetallic phase formation and evolution during homogenization and solution in Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 56, 2827–2838 (2013).

Fan, X., Jiang, D., Meng, Q. & Zhong, L. The microstructural evolution of an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy during homogenization. Mater. Lett. 60, 1475–1479 (2006).

Deev, V. et al. Effect of La addition on solidification behavior and phase composition of cast Al-Mg-Si Alloy. Met. (Basel). 10, 1–12 (2020).

Balaško, T., Vončina, M., Nagode, A. & Medved, J. Influence of La additions on solidification and microstructure in the as-cast state of the aluminium alloy EN AW-7175. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-024-13241-1 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Effect of La Addition on Microstructure and properties of Al-0.2Fe-0.06Cu Alloy. Met. (Basel) 12, (2022).

Yuan, W. H. & An, B. L. Effect of la addition on the microstructures and mechanical properties of 7075 aluminum alloy. Adv. Mater. Res. 152–153, 1810–1813 (2011).

Tang, P. et al. Influence of strontium and lanthanum simultaneous addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of the secondary Al-Si-Cu-Fe alloy. J. Rare Earths. 35, 485–493 (2017).

Medvedev, A. E. et al. Enhancement of mechanical and electrical properties of Al-RE alloys by optimizing rare-earth concentration and thermo-mechanical treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 745, 696–704 (2018).

Jiang, H. et al. The influence of rare earth element lanthanum on the microstructures and properties of as-cast 8176 (Al-0.5Fe) aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 859, 157804 (2021).

Hosseinifar, M. & Malakhov, D. V. Effect of Ce and La on microstructure and properties of a 6xxx series type aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 43, 7157–7164 (2008).

Petrič, M. et al. Solidification behaviour and microstructure of AlSi7Mg cast alloy with addition of Li. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 19, 2084–2092 (2022).

Xu, D. K., Rometsch, P. A. & Birbilis, N. Improved solution treatment for an as-rolled Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy. Part I. Characterisation of constituent particles and overheating. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 534, 234–243 (2012).

Yin, S., Howells, A., Lloyd, D. J., Gallerneault, M. & Fallah, V. Thin strip vs direct chill casting: The effects of casting cooling rate on the As-cast microstructure of AA6005 Al–Si–Mg alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 53, 1928–1933 (2022).

Baserinia, A. R. et al. A numerical study of the direct-chill co-casting of aluminum ingots via fusion™ technology. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 44, 1017–1029 (2013).

Hörnqvist, M. & Karlsson, B. Influence of heat treatment on the cyclic deformation properties of aluminium alloy AA7030. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 479, 345–355 (2008).

Fan, X., Jiang, D., Meng, Q., Lai, Z. & Zhang, X. Characterization of precipitation microstructure and properties of 7150 aluminium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 427, 130–135 (2006).

Waterloo, G., Hansen, V., Gjønnes, J. & Skjervold, S. R. Effect of predeformation and preaging at room temperature in Al–Zn–Mg–(Cu,Zr) alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 303, 226–233 (2001).

Xu, D. et al. Phase transformation and microstructure evolution of an ultra-high strength Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy during homogenization. Mater. Charact. 131, 285–297 (2017).

Cui, Y. & Gourlay, C. M. Growth twinning and morphology of Al45Cr7 and Al13Fe4. J. Alloys Compd. 893, 162318 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Experimental study of the phase relationships in the Al-rich corner of the Al-Si-Fe-Cr quaternary system at 700°C. Int. J. Mater. Res. 106, 470–480 (2015).

Boulet, P., de Weerd, M. C., Gaudry, E., Ledieu, J. & Fournée, V. Single crystal growth, crystal structure and surface characterisation of the binary phase Al 45 cr 7. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1458, 012016 (2020).

Kangas, M. J., Schmitt, D. C., Sakai, A., Nakatsuji, S. & Chan, J. Y. Structure and physical properties of single crystal PrCr2Al20 and CeM2Al20 (M = V, cr): A comparison of compounds adopting the CeCr2Al20 structure type. J. Solid State Chem. 196, 274–281 (2012).

Du, J. et al. Phase equilibria of the Al-Si-La system between 0 and 50 at.% La at 600 and 800°C. J. Alloys Compd. 765, 608–615 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the work by the Slovenian Research And Innovation Agency (ARIS) program P1-0195 (B). We would like to thank Ilse Letofsky-Papst and Maja Vončina for their help with this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tilen Balaško: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing & editing – original draft. Jožef Medved: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Aleš Nagode: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Jiehua Li: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balaško, T., Nagode, A., Li, J. et al. Microstructure evolution during solution annealing of an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloy with La additions. Sci Rep 15, 3845 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88490-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88490-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Influence of Zn Content on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of High-Mg-Containing as-Cast Al-8Mg-0.6Mn-xZn Alloy

International Journal of Metalcasting (2025)

-

Study on Microstructure Control and Properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy by Pulsed Electric Field

JOM (2025)