Abstract

Oxidative stress during semen processing affects sperm membrane integrity, leading to compromised sperm membrane functions and kinematics, often resulting in reproductive losses. The first objective of the present study explored the effect of Quercetin (QUE) on seminal parameters, i.e., total antioxidant capacity (TAC), as well as sperm viability, DNA fragmentation, kinematics, intracellular calcium, and apoptosis. The second objective evaluated fold changes in the transcription of apoptotic regulatory (Bax, Bad, Bcl2, Bcl2L1, Fas, FasL, and Caspase 3, 8, 9, and 10) and calcium-regulating CatSper-1,2,3 and 4 genes of the buck spermatozoa. The final objective was fertility trial of negative control and best-performing treatment group. The study analysed 36 ejaculates from 6 bucks, each ejaculate was then divided into 5 parts and extended using TRIS extender with different concentrations of QUE. The negative control (C) consists of extended semen without the addition of QUE, whereas positive control (T1) had been added with vitamin E at a concentration of 3 mmol/mL. Furthermore, treatment groups 2, 3, and 4 (T2, T3, T4) were supplemented with 10, 20, and 30 µmol of QUE/mL of extended semen. The samples at the post-thaw stage were evaluated for seminal parameters as described in the objectives. Group T3 supplemented with 20 µmol/mL QUE was observed with the best results. QUE at 20 µmol/mL concentration significantly enhanced semen TAC along with various sperm parameters, i.e., viability, kinematics, intracellular calcium and plasma membrane fluidity. QUE at 20 µmol/mL concentration also downregulated pro-apoptotic and upregulated anti-apoptotic genes. Similarly, QUE downregulated caspase family genes and upregulated CatSper genes. Field fertility trials showed improved conception rates in the treatment group. QUE-induced control of oxidants might have contributed to higher TAC and viability. The upregulation of anti-apoptotic and downregulation of pro- and other apoptotic regulatory genes, as well as the upregulation of CatSper genes, suggest a regulatory effect of QUE on sperm apoptosis, and calcium homeostasis. Lower proportion of apoptosis and higher normal intracellular calcium, as estimated through flow cytometry, further validated our findings. Our field fertility trial yielded 58.3% conception rate in the treatment group as compared to 27.6% in the control group. QUE at 20 µmol/mL concentration significantly improved the antioxidant capacity, intra-cellular calcium concentration, and kinematics of goat sperm and subsequently resulted in better fertility as compared to control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reproduction is a complex phenomenon comprising cellular activity and signalling resulting in gametogenesis, followed by fertilization, zygote development, and ultimately leading to the production of healthy, viable offspring through subsequent developmental stages. Modifications in sperm activity and morphology, are crucial for successful oocyte fertilization. These modifications encompass sperm kinematics, chemotactic movement, acrosomal reaction, and the union of the sperm and oocyte plasma membranes. The oocyte undergoes morphological, metabolic, and electrical modifications after this union, leading to effective fertilization and the start of embryonic development1. The main function of spermatozoa is to activate and fertilize the oocyte, which is supported by functional membranes (plasma, acrosomal, and mitochondrial membranes) and sperm kinematics. Sperm acquire functional competency through a series of morphological and metabolic transformations. These processes are closely associated with modified electrical properties within spermatozoa, facilitated by the activity of ion channels located in its plasma membrane2. However, semen cryopreservation triggers oxidative stress, leading to enormous generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), resulting in rapid depletion of antioxidants followed by early apoptotic changes and lipid peroxidation3,4. These events subsequently result in subtle changes in sperm membranes, including impaired plasma membrane fluidity, integrity and apoptotic changes4,5. Compromised spermatozoa often results in unsuccessful fertilization, however, in instances of successful fertilization, the zygote undergoes atypical developmental changes during cleavage and early embryonic stages6. Apoptotic changes are defined by certain variations in the shape of cells, such as DNA fragmentation, formation of blebs with organelles surrounded by a membrane, and reduction in cell size. The B-cell lymphoma (Bcl) protein family is known for its role in controlling programmed cell death (apoptosis) in several types of cells. Some members of this family, such as Bcl2 and Bcl2L1, possess the ability to impede apoptosis, but others, like Bax, Bak, and Bad, have the capability to initiate apoptotic processes7. During fertilization, various types of RNAs are transferred from male to female gametes. Several of these RNAs may be involved in regulating fertilization and the early phases of embryonic development8. Transcriptional changes can occur in spermatozoa throughout the process of cryopreservation9. Prior research has indicated that cryopreservation might impair mitochondrial functions and influence both external and internal apoptotic mechanisms, potentially leading to apoptosis. These effects may be attributed to, plasma membrane damage and other minor changes10. The sperm cells within the female genitalia are exposed to higher levels of biochemical substances11,12. This facilitates adenyl cyclase enzyme activation, thus stimulating the production of cyclic AMP and preparing protein kinase A for action. The complete sequence of events enables the membrane to become more negatively charged, which triggers the activation of the sperm cationic channel known as CatSper, as well as the voltage-gated calcium channel13,14. CatSper is a principal calcium-regulating ion channel located solely in the flagellar region of spermatozoa15. The influx of calcium through the active CatSper channel induces hyperactivation, thereby enhancing sperm transport and subsequent fertilisation processes. The CatSper channel comprises 10 subunits, of which CatSper 1, 2, 3, and 4 serve as pore-forming units, while the others function as auxiliary units16. Elevated intracellular calcium concentration results from calcium influx largely via CatSper, enhances sperm motility, and facilitates hyperactivation, capacitation, and acrosomal reaction. The acrosome reaction facilitates the initial penetration of extracellular oocyte membranes, subsequently leading to fertilization. The aforementioned steps, namely capacitation, hyperactivation, and acrosomal response, are also regulated by calcium, which plays a crucial role in promoting fertilization indirectly15,16,17.

QUE is a flavone component that can be found in various berries and vegetables. QUE is a powerful antioxidant that effectively traps reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), making it highly effective at eliminating oxidants3. In addition, QUE regulates the lipid component of plasma membranes of various cells and possesses enzymatic modulation and repair capabilities. Furthermore, QUE in semen regulates the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), which in turn regulates subtle membrane modifications and enhances the viability of sperm cells following freezing and thawing3. QUE was also reported to have regulatory effects on sperm kinematics18. Moreover, recently, it has been reported that QUE impacts the functionality of CatSper channel genes19.

The first objective of this study was to explore the effect of QUE on the total antioxidant capacity of extended buck semen, as well as viability, DNA fragmentation, kinematics, intracellular calcium level, apoptotic changes and membrane fluidity of buck spermatozoa. Similarly, the second objective was to explore fold changes in the transcription of apoptotic regulatory and calcium-regulating genes in buck spermatozoa. The final objective was a field fertility trial on receptive doe using buck semen from the negative control and best-performing treatment group.

Materials and methods

Collection of semen ejaculates and supplementation of QUE

The experiment was carried out with authorisation and in compliance with the protocols of the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC/BVC/2023/02), adhering to ARRIVE principles (https://arriveguidelines.org). Our investigation included six apparently healthy and sexually mature adult Black Bengal bucks, aged between 2 to 3 years and weighing approximately 20 to 25 kg, housed at the goat unit. The current study compared results of test and control groups. The sample size for the study was determined based on prior research3. The study included ejaculates showing mass motility of 4 or above and freshly extended semen exhibiting progressive motility exceeding 80%. Blinding was implemented in such a way that the selection of all animals, treatment dosages, test execution, data collection, and statistical analysis were conducted by separate investigators. The study examined a total of 36 semen collections from six sexually matured proven donor bucks. These ejaculates were obtained thrice a week through the use of buck-specific artificial vagina. The freshly collected semen was divided into 5 parts and extended using glycerylated TRIS-egg yolk citrate. The negative control (C) was devoid of QUE whereas positive control (T1) comprised 3 mmol vitamin E/mL of extended semen. Treatment categories containing QUE at a concentration of 10, 20, and 30 µmol/mL of extended semen were named T2, T3, and T4, respectively. Sperm concentrations in all the groups were kept at 200 million/mL of extended semen. These samples were cryopreserved as per standard protocol4,20. Briefly, extended semen samples at ambient temperature were equilibrated in a chilled cabinet for 4 h and thereafter filled and sealed in 0.25 mL French straws using a sealing-filling machine (MRS-I, IMV, FRANCE). Subsequently, these packed samples at chilling temperature were transported into the chamber of a programmed freezer (Digicool, IMV, France) to attain − 140 °C. The frozen semen straws were later immersed in liquid nitrogen to achieve a final temperature of -196 °C. Thawing was carried out by placing frozen semen straw at 35 °C for 40 s.

The samples were evaluated at the post-thaw stage for TAC of the semen, as well as sperm, chromatin dispersion and kinematics through CASA, along with flow cytometry parameters i.e., viability of the spermatozoa, intra-cellular calcium concentration, apoptotic changes and fluidity of the sperm plasma membrane. The treatment group resulted best in the above-mentioned parameters, i.e., T3 (20 µmol QUE) underwent further evaluation for the relative quantification of transcripts of the apoptotic and CatSper genes using SYBR green chemistry. Comparisons for the relative change in expression of target genes were made between the negative control (C) and treatment groups (20 µmol QUE). The data obtained in the form of cycle threshold (Cq) were evaluated for change in fold expression for apoptotic and CatSper channel genes. Furthermore, these two groups, i.e., treatment (T3) and negative control, were evaluated for in vivo fertility tests in field conditions. For this purpose, a total of 3200 artificial inseminations (1600 AI for each group in rural parts of two provinces) were performed with the help of a non-government organisation. Successful parturition and abortions were included under fertility.

Evaluation of the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of semen

Cryopreserved semen samples after thawing, were analysed for TAC using an antioxidant kit (Cayman Chemicals item no. 709001, USA). The main working principle of the assay is to prevent the conversion of ABTS into oxidised ABTS (ABTS-O) through metmyoglobin. The produced ABTS-O was read at 750 nm wavelength in a calorimeter. The procedure of assay followed in our lab was as per the previous description21, with slight modifications. In brief, prior to commencement of the assay, the Trolox reference and substances were prepared in accordance with the directions provided by the manufacturer. Semen samples and 10 µL of Trolox reference were added to the appropriate plate containing ninety-six wells. Subsequently, each well was supplemented with chromogen and metmyoglobin in 150 and 10 µL volumes, respectively. Hydrogen peroxide (40 µL) was mixed to start the reaction. The wells were covered and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, followed by reading the absorbance at 750 nm. The mean absorption of every standard and sample was calculated to determine the reaction rate. The standard average absorbance in relation to the final plotting of the Trolox equivalent (mM) for the standard curve for every run was used for the identification of the unknown samples. The total antioxidant content of each sample was determined by obtaining values from the equation derived by the linear regression of the standard curve. The following equation was used to calculate the resulting antioxidant capacity of every sample.

\({\text{TAC }}\left( {{\text{mmol of Trolox Equivalent}}} \right){\text{ }}=\frac{{{\text{Average}}\;{\text{absorbance}}\;{\text{of}}\;{\text{semen}}\;{\text{sample}}\;({\text{Y-intercept}})}}{{{\text{Slope}}}} \times {\text{dilution}} \times {\text{1}}000\)

Analysis of sperm kinematics

Sperm kinematics was assessed employing the CASA (Computer Assisted Semen Analyser, IVOS II, Hamilton Thorne, USA) based on the earlier adopted methodology3. The movement patterns of sperm were analysed by considering their morphological dimensions, with a specific focus on the structural characteristics of the head and tail regions. A 2 µL semen sample was used in an 8-chambered Leja slide (IMV Technologies, France). The analysis of four to six fields, each containing about a thousand spermatozoa, was part of the observation. The following parameters were observed: the percentage of total motility as well as progressive motility of spermatozoa; velocity parameters, like path velocity, curvi-linear velocity, and straight-line velocity in µm/s; percent of linearity, straightness, and wobble; frequency- beat cross (Hz); and the displacement of amplitude as well as lateral head in µm. The suggested application program was fixed for frame count and capture at 30 (Nos.) and 60 Hz, respectively. The temperature during the analysis was kept at 35 °C.

Evaluation of DNA fragmentation through sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) method

SCD is the basic principle of DNA fragmentation assessment. Chromatin of spermatozoa responds differently when subjected to nucleo-protein depletion with DNA (fragmented or non-fragmented). Moreover, nucleotides of the treated sperm possessing null to negligible DNA break produce large ‘Halo’ of DNA loop spreading, whereas DNA with massive breakage will show negligible halo, or sometimes it may not produce halo at all. DNA fragmentation was assessed using CASA (IVOS II, Hamilton Thorne, USA). In brief, the assay was conducted using Caprine Halomax kit, which is developed for goat sperm DNA fragmentation analysis. The semen sample was diluted with PBS at 37 °C to achieve 15–20 × 106 spermatozoa/mL. The sperm aliquot (25 µL) was poured into a microcentrifuge tube. Simultaneously, an agarose gel (50 µL) was heated at 95–100 °C for 5 min. The same was maintained at 37 °C for 5 min to attain equilibration. Thereafter, melted agarose was poured into MC tubes containing sperm suspension followed by gentle mixing. A drop of sperm suspension was put on pre-coated wells of slide, covered with a large-sized (22 × 22 mm) glass cover slip; furthermore, gentle pressure was applied to eliminate air bubbles. The glass slide was kept over a chilled (4 °C) metal tray and placed in the chilling cabinet of the refrigerator for 25 min to facilitate the solidification of agarose. Now the glass slide was moved from the refrigerator to the room, and coverslip was removed via gentle sliding. Now the glass slide was kept horizontally in a petri dish, and wells of the slide were immersed in freshly prepared acidic denaturing solution (80 µL HCL mixed with 10 µL distilled water) for 7 min, followed by flooding the wells with lysis solution at 22 °C for 5 min, thereafter washing with distilled water. Finally, wells of the slide were made dry through successive treatments of 70%, 90%, and absolute ethanol, each for 2 min, followed by drying in air. Furthermore, staining dye FluoroFrag™ and diluent antifade solution were thawed at 37 °C in a dry bath. Antifade solution (1 mL) was added to the amber coloured tube containing the stain and then subjected to vortexing for 30 s. Staining of sperm was carried out by placing prepared slide on a horizontal surface, and 3 µL of prepared stain solution was poured on each well, then glass coverslip (22 × 22 mm) was applied over each well and the slide was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Finally, these ready slides were evaluated using IVOS II (Hamilton Thorne, USA) (Fig. 1).

Assessment of spermatozoa using flow cytometry

Sperm-specific flow cytometry was carried out as per the previously described protocol3.

Flow cytometric evaluation of viability of spermatozoa

Flow cytometric analysis was carried out for viability and plasma membrane integrity of spermatozoa using SYBR-14 and propidium iodine (PI) through LIVE/DEAD™ sperm viability kit (L-7011, Invitrogen, USA). Briefly, semen samples were diluted by mixing 10 µL of semen in 190 µL of easy buffer B (EBB, IMV India). Similarly, a working solution of SYBR-14 dye was also prepared by placing 1 µL of dye and 49 µL of triple-distilled water. A volume of 200 µL of the diluted samples were transferred into cytometry vials, followed by the addition of 5 µL of working dye solution. The samples were combined and subjected to incubation at ambient temperature for a duration of 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were added with 5 µL of PI, and the solution was allowed to incubate for an additional 5 min prior to analysis.

Flow cytometric evaluation of apoptosis and membrane fluidity changes in spermatozoa

Flow cytometric assessment of apoptotic and necrotic changes on spermatozoa was conducted by employing Merocyanine-540 and YO-PRO1 reagents (YO-PRO™ 1 iodide 491/509 REF-Y 3603). Merocyanine and Yo-Pro-1 are both fluorescent dyes that were used to study membrane fluidity membrane integrity and apoptosis.

Briefly, a working solution of merocyanine was prepared by diluting 1µL stock solution (10X) with 9 µL DMSO. Similarly, working solution of YO-PRO-1 (1 mM) was also prepared prior to start the experiment. To initiate the experiment, 190 µL of EBB was poured into the designated well. The experimental procedure involved the addition of 1 µL merocyanine (1X) and Yo PRO-1 (1 mM). The mixture was then homogenised using a 200 µL tip and then thawed semen (10 µL) was introduced into the designated well. The mixture was then subjected to incubation at a temperature of 37 °C for a duration of 10 min while being shielded from light. A total of five distinct populations of spermatozoa were assessed: sperm exhibiting typical fluidity of the membrane, transitional phase, elevated membrane fluidity, apoptotic changes, and necrotic spermatozoa.

Flow cytometric evaluation of intracellular calcium level in spermatozoa

The intracellular calcium assay in sperm cytoplasm was performed using the Flou-4 NW calcium kit with the protocol prescribed by the manufacturer. Briefly, initial solution of probenecid at 250 mM and 1 mL of assay buffer (C) in a vial of probenecid (B) was taken, followed by vortexing till dissolution, and finally, the solution was kept at -20 °C. Small aliquots of 100 µL double-strength dye (2X), 5 mL of assay buffer, and 100 µL of the initial solution of probenecid in the bottle of flourochrome (A) was mixed till complete solubilization (1–2 min). Similarly, semen samples were prepared with an adjustment of 1,25,000 cells/well of 50 µL capacity. Samples were incubated for half an hour at 37 °C followed by another 30 min at ambient temperature in absence of light. Events were recorded in the flow cytometer using calcium assay setup.

The second objective of the study included the evaluation of expression patterns of various apoptotic and calcium-regulating genes and the third objective evaluated field fertility trial. However, the comparison was performed between negative control group and best performing group of first objective. Results of first objectives indicated that group T3 containing 20 µmol/mL QUE was superior in all the seminal parameters tested. Thus, quantification analysis of various genes and field fertility trials were carried out for negative control and T3 group only. For better clarity, the T3 group is now renamed as treatment (T) group.

Gene expression studies

Specific primer designing for the gene of interest

Primers specific to gene of interest were designed via NCBI site using (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) in conjunction with Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) Primer Designing Tool. The list of primers is presented in supplementary file no. 2. RNA isolation from spermatozoa was carried out as per standard protocol followed in our lab (detailed description is given in supplementary file 3).

Standardization of primers for apoptosis and CatSper genes

Primers designed for pro and anti-apoptosis as well as death ligand genes along with CatSper channel genes, were subjected to standardization using gradient temperature and time settings. Similarly, PCR was implemented for gene amplification. Each primer was tested for its efficacy using standard curve obtained using qPCR (detailed description is given in supplementary file 4).

Assessment of relative expression of genes of interest with housekeeping genes using real time PCR

Each standardized gene was further subjected to specificity check using qPCR. Reaction mixture was prepared in PCR tubes by adding 2X master mix followed by the addition of forward and reverse primer of each gene (1 µL) along with cDNA and NFW (1 µL each). The prepared reaction mixture was placed in qPCR (Aria MX with Agilent Aria software v1.5 Agilent technologies) with standard protocol mentioned in supplementary file 4.

Field fertility trial

The treatment group (previously referred to as T3) and the negative control group (C) were evaluated for in vivo fertility under field conditions. The artificial inseminations (AI) of each aforesaid treatment (n = 1600) were carried out with the assistance of a non-governmental organization. Each doe was inseminated twice, with a single straw used for each insemination, administered at 24 and 36 h following the onset of estrus signs. Pregnancy was diagnosed via ultrasonographic examination of each doe on day 40 using a trans-abdominal ultrasound probe (SUN-806G, Sunbright, China). These findings were revalidated by quantifying successful parturition and abortion instances.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the first objective were initially assessed for uniformity using Levene’s test, and uniformly distributed data was subsequently evaluated with one-way ANOVA using SPSS v.26. The Duncan multiple comparison was used to examine the means data of all the groups for significant differences. However, TAC and DNA fragmentation with non-homogeneity were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test through GraphPad Prism software. The data obtained from second objective after every extension stage, and the relative expression of the qPCR product were estimated using the following equation: 2(-∆∆Ct). The level of significance was calculated using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Effect of QUE on total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of semen

TAC of semen at the post-thaw stage of cryopreservation showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) across the negative control and QUE-treated groups. TAC concentration in all treatment groups has significantly increased (p < 0.01) when compared to the negative control group. The TAC results has been presented in Fig. 2. Mean ± SE% values of TAC have been presented in Table 1 of the supplementary file 1.

Total anti-oxidant capacity assay

Effect of QUE on sperm viability and plasma membrane integrity assessed through flow cytometry

The impact of QUE on the viability and integrity of the plasma membrane of cryopreserved buck spermatozoa has been shown in Fig. 3. The mean values of viability and plasma membrane integrity of spermatozoa at the post-thaw stage of cryopreservation showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treated groups. However, within treated group T2 and T4 did not differ significantly. Nevertheless, the T3 group, which was supplemented with 20 µmol QUE, exhibited significantly (p < 0.01) higher proportion of live sperm having intact plasma membrane in comparison with all other groups. Dot plot gating of a representative sample and Mean ± SE% values of sperm viability and plasma membrane integrity have been presented in Fig. *1 and Table 2 of the supplementary file 1, respectively.

QUE on the sperm viability and plasma membrane integrity of buck semen at the post-thaw stage was assessed. The data presented include the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (n = 36). Different lowercase characters shown as superscripts demonstrated a statistically significant distinction (p < 0.01).

Effects of QUE on sperm movement using computer-assisted sperm analysis

The impact of QUE on the movement patterns of cryopreserved buck sperm has been demonstrated in Figs. 4 and 5. Motility parameters (total and progressive motility) of cryopreserved sperm were reported with significant variations (p < 0.01) between negative control and treated groups. Among the treated groups, T3 group (20 µmol QUE), showed significant improvement in terms of total and progressive motility. Similar trend followed in other kinematics parameters. Mean ± SE% values of sperm kinematics have been presented in Table 3 of the supplementary file 1.

Effect of QUE on DNA fragmentation in cryopreserved spermatozoa evaluated through SCD

Cryopreserved spermatozoa with fragmented DNA have been depicted in Fig. 6. The percentage of spermatozoa with fragmented DNA did not differ significantly among the groups. Mean ± SE% values of DNA fragmentation have been presented in Table 4 of the supplementary file 1.

Impact of QUE on apoptosis and membrane fluidity of cryopreserved spermatozoa

The impact of QUE on the process of apoptosis as well as the fluidity of sperm plasma membrane after thawing is illustrated in Fig. 7. The mean values of apoptosis and membrane fluidity, showed significant differences (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treated groups. The mean (± SE) percentage of normal sperm showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) between negative control and treated groups. Group T3, which received supplementation of 20 µmol QUE, had significantly higher proportion of normal spermatozoa compared to all other groups (p < 0.01). Similarly, amongst all groups, T3 had a significantly (p < 0.01) reduced proportion of spermatozoa with higher membrane fluidity, as compared to groups C, T1, and T2. The mean (± SE%) of transitional sperm differed considerably (p < 0.01) across the negative control and treated groups. However, there was no significant difference seen between treatment groups, T1, T2, and T4. Sperm proportion, undergoing apoptosis showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treated groups. Group T3, exhibited a significantly lower (p < 0.01) proportion of apoptotic spermatozoa amongst all groups. Dot plot gating and Mean ± SE% values of membrane fluidity and apoptosis have been presented in Fig. *2 and Table 5 of the supplementary file 1, respectively.

Effect of QUE on intracellular calcium level in spermatozoa

The effect of QUE on intra-cellular calcium level of buck sperm at post thaw stage of cryopreservation has been presented in Fig. 8. Mean (± SE) values of intra-cellular calcium level exhibited significant (p < 0.01) difference between negative control and treated groups.

The mean (± SE) proportion of spermatozoa with reduced intra-cellular calcium concentration exhibited a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treated groups. However, there was no statistically significant difference noticed between treatment groups, T2, T3, and T4. The mean (± SE%) of spermatozoa with normal intra-cellular calcium level showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treated groups. Among treatment groups, T3 supplemented with 20 µmol QUE had significantly (p < 0.01) higher spermatozoa with normal intra-cellular calcium level as compared to T1, T2, and T4 groups. However, there was no statistically significant difference seen among treatment groups T1, T2, and T4. The mean (± SE%) of spermatozoa with increased intra-cellular calcium level showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the negative control and treatment groups. Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant distinction detected amongst treated groups, T2, T3, and T4. Mean ± SE% values of intra-cellular calcium and dot plot gating have been presented in Table 6 and Fig. *3 of supplementary file 1, respectively.

QUE on intra-cellular calcium level of cryopreserved buck spermatozoa. The data presented includes the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (n = 36). Different lowercase characters shown as superscript demonstrated a statistically significant distinction (p < 0.01). Different lower-case letters (a, b, c) in each group of bars differed significantly (p < 0.01).

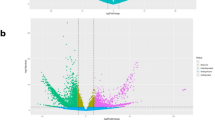

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of apoptotic and CatSper gene at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Objective 2 included qPCR analysis of the relative abundance of Apoptotic and CatSper gene transcripts using SYBR green chemistry. The comparison was made between negative control and best treatment group based on results obtained from objective 1. Various sperm function tests and oxidative-antioxidant status yielded significant (p < 0.01) improvement in group T3 supplemented with 20 µmol QUE/mL of buck semen extender. Thus, comparison for relative change in expression of target genes were made between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol QUE). The data obtained in form of CqCycle threshold were evaluated for change in fold expression as described by Livak and Schmittegn (2001). Mann-Whitney U test was carried out to evaluate the level of significance.

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of pro-apoptotic genes in buck spermatozoa at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Pro-apoptotic genes i.e., Bad and Bax were evaluated for change in expression between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol). Mean (± SE) of fold change expression of Bax and Bad genes were observed as 0.68 ± 0.031 and 0.96 ± 0.021, respectively against negative control. Bad gene showed non-significant difference whereas Bax gene was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated, as compared to negative control. Relative expression of pro-apoptotic genes having significant difference has been presented in Fig. 9.

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of anti-apoptotic genes in buck spermatozoa at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Anti-apoptotic genes i.e. Bcl2 and Bcl2L1 were evaluated for relative change in expression between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol). Mean (± SE) of fold change in expression of Bcl2 gene was non-significant, however, Bcl2L1 was significantly (p < 0.01) upregulated in treatment group as compared to negative control. Mean (± SE) of fold change expression of anti-apoptotic gene i.e. Bcl2 and Bcl2L1 were observed as 0.84 ± 0.032 and 2.84 ± 0.011, respectively against negative control. Relative expression of anti-apoptotic genes having significant difference has been presented in Fig. 9.

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of apoptotic-caspase family genes in buck spermatozoa at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Relative expression of caspase family genes i.e. Caspases 3,8,9, and 10 were evaluated between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol). Caspase 3 and caspase 8 were non-significantly expressed, whereas caspase 9 and caspase 10 were significantly (p < 0.01) downregulated in treated group as compared to negative control. Mean (± SE) of fold change in transcripts of apoptotic gene i.e. Caspase 3, 8, 9 and 10 were observed as 0.89 ± 0.01, 0.92 ± 0.13, 0.81 ± 0.01 and 2.21 ± 0.02, respectively in treatment group against negative control. Relative expression of apoptotic-Caspase family genes having significant difference has been presented in Fig. 9.

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of apoptotic-Fas and FasL genes in buck spermatozoa at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Relative expression of Fas and FasL gene were evaluated between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol), however, both the genes expressed non-significant difference between negative control and treatment group. Mean (± SE) of fold change in transcripts of apoptotic gene i.e. Fas and FasL were observed as 0.97 ± 0.005 and 0.92 ± 0.017, respectively in treatment group compared to negative control.

Effect of QUE treatment on relative quantification of transcripts of calcium regulating CatSper family gene in buck spermatozoa at post-thaw stage of cryopreservation

Relative expression of CatSper 1,2,3 and 4 genes were evaluated for their expression between negative control and treatment group (20 µmol). Expression of CatSper 1,2 and 4 were significantly (p < 0.01) upregulated in treatment group. Mean (± SE) of fold change in transcripts of CatSper channel gene i.e. CatSper 1,2,3 and 4 were observed as 2.98 ± 0.031, 3.24 ± 0.087, 1.06 ± 0.072 and 1.22 ± 0.067 respectively in treatment group against negative control. There was a non-significant deviation observed in CatSper 3 gene expression between negative control and treatment.

Relative expression of CatSper 1,2,3 and 4 genes have been presented in Fig. 10.

Effect of QUE treatments on in-vivo fertility trial

Our field fertility trial yielded a 58.3% conception rate in treatment group as compared to 27.6% in the negative control group.

Discussion

The phenomenon of excessive RONS production during the freezing and thawing of sperm cells lead to oxidative stress that damages the membrane integrity, resulting in compromised membrane functions and kinematics3. Antioxidants present in the semen regulate oxidative stress through neutralizing RONS; therefore, semen with higher antioxidant capacity can resist oxidative stress-induced damage3. The antioxidant capacity of semen consists of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components21. To assess the antioxidant potential of cryopreserved semen, multiple studies were conducted through evaluations of these compounds in both groups (enzymatic or non-enzymatic) and individual settings. However, evaluating individual antioxidants or enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as a group does not accurately represent the true antioxidant capacity of semen22,23. Thus, in the present study we evaluated TAC of semen, which represents the actual antioxidant strength. Our study reported superior TAC value in all the treated groups; however, the best TAC values were observed in the T3 group. The best TAC value in T3 is probably due to the presence of QUE in the most effective dose, i.e., 20 µmol/mL, which mitigated the drainage of naturally present antioxidants to its maximum extent. Several workers reported RONS-induced DNA damage in sperm cells, resulting in significant occurrence of both single- and double-strand DNA breaks24,25. The precise understanding of DNA fragmentation within spermatozoa during cryopreservation is still lacking. Existing research indicates DNA damage in spermatozoa is linked to a rise in RONS during freezing and thawing rather than the triggering of caspases, which initiates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis26,30. Our DNA fragmentation analysis showed non-significant difference despite the higher TAC of the QUE-treated groups, which controlled the RONS concentration in the treated sample in a highly significant manner3. Our results are further supported by previous works that reported cryopreservation-induced early apoptotic changes yet non-significant differences in damaged sperm DNA27,28.

Unlike the majority of studies conducted in humans, where semen from sub-fertile and fertile patients were compared, whereas our study compared the semen of apparently healthy breeding bucks against various treatment doses of QUE. This could be the probable reason for the non-significant difference in the proportion of sperm having fragmented DNA between the treatment and control groups. Semen containing more leukocytes (pathological condition) are more prone to DNA fragmentation. Therefore, oxidative stress during cryopreservation, coupled with a higher concentration of leukocytes, may lead to a higher probability of DNA fragmentation25,26.

Spermatozoa possess distinct kinematic properties that are exclusive to these specialized cells. The diverse velocity patterns and motions of the spermatozoa arise from its energy metabolism along with its reaction to the surrounding environment. Sperm motility in a forward direction with adequate velocity is also essential for fertilization. Motion characteristics play a crucial role in the fertilization process in every species18. Studies have shown that the fertilization rates of goat oocytes in in-vitro conditions are positively correlated with the increased mobility of sperm29. Therefore, the evaluation of the proportion of motile spermatozoa is a crucial factor. A robust positive link was identified between LIN and STR values30. The CAS analyzer in our study classified sperm into various subpopulations, namely distance indicators, i.e., DAP, DSL, and DCL, as well as velocity indicators, i.e., VAP, VSL, and VCL. Furthermore, our study reported a significant (p < 0.01) difference between treated and negative control samples in terms of distance and velocity indicators. QUE in semen improved the movement of sperm and controlled RONS concentration3. Our findings were supported by earlier findings where sperm with greater levels of VCL, VSL, and VAP were associated with higher fertility rates31. Consequently, these velocity measures are dependable indices of fertility18. Similarly, our research reveals that the groups treated with QUE had greater average values for distance markers including DAP and DSL. Similar results were reported in goat semen with lower concentrations of QUE, which can be attributed to differences in the composition of semen extenders31,32. In the present study, the LIN, STR, and WOB values in the QUE-treated groups improved significantly, since these values are ratios of the velocity indicators; therefore, higher values of these parameters also suggest better sperm motility. Our results are corroborated by previous studies that found a positive correlation between higher values of linearity, straightness, and wobbles with improved sperm motility29,33,34,35.

Excessively produced RONS alters membrane fluidity and induces apoptotic changes. Apoptosis is characterized by distinct changes in the cell structure, including fragmentation of the nucleus, the formation of membrane-enclosed apoptotic blebs containing organelles, and a reduction in cell size. The B-cell lymphoma (Bcl) protein family is recognized for its involvement in regulating apoptosis in several cell types. Certain members of this family, including Bcl2 and Bcl2L1, can inhibit apoptosis, while others, such as Bax, Bak, and Bad, have the potential to trigger apoptotic changes7. In the procedure of fertilization, different categories of RNAs pass through sperm cells to the oocyte. It is possible that a number of these RNAs play a role in controlling conception and the initial stages of embryonic growth8. Transcriptional changes may take place in spermatozoa at the time of freezing and thawing9. However, earlier studies have shown that during cryopreservation, damage to mitochondrial functioning as well as subtle changes in the plasma membrane may trigger extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic mechanisms that might result in apoptosis3,10. Hence, the mRNA abundance of genes associated with programmed cell death was examined in the present study. Specifically, the expression of two pro-apoptotic genes, namely Bad and Bax, were assessed to determine any alterations between the negative control and treatment group. The target genes Bax expressed significant (p < 0.05) variation between treatment and negative control groups. Downregulation of the pro-apoptotic Bax gene in the treatment group indicated anti-apoptotic property of QUE. Furthermore, the expression levels of two anti-apoptotic genes, namely Bcl2 and Bcl2L1, were assessed for their relative expression. A significant (p < 0.01) difference was observed in the expression of Bcl2L1 gene between negative control and treatment groups. The findings demonstrated that the supplementation of QUE at a concentration of 20 µmol resulted in a considerable reduction in Bax and increase in Bcl2L1 mRNA expression. The positive benefits seen may be attributed to a reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in samples treated with QUE. Furthermore, the results suggested that the addition of QUE (20 µmol) could enhance the post-thaw quality of sperm following cryopreservation and confer resistance to the freezing and thawing processes owing to its anti-apoptotic action. The up- and down-regulation of anti-apoptotic (Bcl2L1) and pro-apoptotic (Bax) genes in QUE (20 µmol)-treated semen is corroborated by another study with the addition of antioxidant L-carnitine in mouse semen32.

The present study also evaluated the relative mRNA expression of two important genes associated with apoptosis, namely, Fas and FasL. These genes are linked to the extrinsic pathway of the apoptotic cascade. However, in our study, we observe non-significant changes in these genes. The possible explanation of this outcome can be traced to the earlier findings in rats, which indicate that an increase in the expression of the Fas-receptor complex is linked to the programmed cell death of spermatocytes in the initial stage of sperm production36,42. FasL triggers the activation of Fas, thus forming a Fas-receptor complex that initiates a pre-apoptotic demise signal in the cell that possesses these receptors37. The presence of the Fas-receptor complex has been observed in testicular tissue38. A recent study revealed that the level of FasL transcription was increased in testicular cells of individuals suffering from a pathological condition of the testis, indicating a potential association with the removal of spermatocytes displaying Fas expression and their abnormal development39. Our study was conducted on mature spermatozoa, and their non-significant expression may explain the possibility that only spermatocytes during their developmental or maturation phase may express these genes. Changes in germ cell maturation during meiosis and the post-meiotic phase may be connected to a rise in the expression of the Fas gene, thus facilitating the elimination of defective gametes40,41. Present study also evaluated the expression pattern of genes associated with the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, namely, caspases 3, 8, 9, and 10. Our results indicate a positive effect of QUE on downregulation of caspase 9 and 10 genes owing to its anti-apoptotic action. Our findings align with the previous research that reported expression of apoptotic genes of caspase family in cat sperm in different breeding seasons42. In an animal model, cryopreservation augmented the occurrence of apoptotic markers, such as changes in mitochondrial activity, activation of caspases, enhanced membrane permeation, and external appearance of phosphatidylserine4,43.

A recent study showed a substantial correlation between cryopreservation and the upregulation of caspases 3, 8, 9, 10 and the reduced mitochondrial membrane27,44. The study of the differences between fresh and cryopreserved sperm cells showed that cryopreservation greatly increased the number of spermatozoa with activated caspases45,46. Therefore, the release of phosphatidylserine (PS) to external surface of the sperm plasma membrane, followed by triggering of caspase family genes and the breakdown of chromosomes, are regarded as indicators of apoptotic changes7,47.

Spermatozoa are mobile cells that can reach fertilization site, i.e., the oviduct. These spermatozoa at oviducal surface are exposed to a high concentration of biochemical substances. This facilitates adenylate cyclase activation, which in turn stimulates cAMP productivity and prepares protein kinase A for action. The complete sequence of events enables the membrane to become more negatively charged, which triggers the activation of the sperm cationic channel known as CatSper, as well as the voltage-gated calcium channel13,14. Elevated intracellular calcium concentration arises from the entry of calcium, mostly aided by CatSper, leading to heightened activity and promoting fertilization. The acrosome response is a crucial process that enhances membrane fluidity, making it essential for sperm to acquire the ability to fertilize. The pre-fertilization events, namely capacitation, hyperactivation, and acrosomal response, are regulated by calcium, which plays a crucial role in promoting fertilization indirectly15. The CatSper channel has a vital role in controlling the influx of calcium into sperm cells, thereby playing a significant part in determining fertility. CatSper is an exceptional calcium-regulating channel found in the primary portion of sperm flagella16. It is proved that CatSper regulates sperm motility via chemotaxis48,49. The entrance of calcium into the cell through CatSper is considered a significant element that triggers the hyperactivation of spermatozoa16,50. In addition, it was reported that spermatozoa devoid of CatSper were incapable of achieving hyperactivation and therefore unable to participate in fertilization51. Similarly, CatSper is believed to trigger the rapid rise of intracellular calcium levels in the flagella, followed by a quick increase in the head region of spermatozoa. This is achieved by utilizing the calcium reserve located at the sperm neck52. Previous studies revealed that antioxidants can regulate the gene expression of the CatSper channel, thus resulting in better motility and finally fertility52,53,54,55. In present study, relative expression of CatSper 1,2,3 and 4 genes were evaluated for their expression in negative control and treatment groups. Treated group exhibited upregulated expression of CatSper 1, 2, and 4 in a significant (p < 0.01) manner. Our findings were in concurrence with previous work where it was observed that the presence of antioxidants reduced ROS concentration during cryopreservation, leading to the preservation of a fully functional CatSper channel in buffalo spermatozoa19. Our results indicate a positive effect of QUE in regulating calcium channels in spermatozoa. These findings were potentiated by flow cytometric evaluation of intracellular calcium concentration of spermatozoa treated with QUE in different dose rates. T3 containing 20 µmol QUE was reported with a significantly higher proportion of sperm having normal intracellular calcium concentration. This finding is again validated by the sperm kinematic evaluation, which showed significant improvement in the proportion of progressively motile spermatozoa subjected to 20 µmol QUE addition. Furthermore, QUE-treated sperm showed significantly improved distance and velocity parameters. All these findings indicate the beneficial effect of QUE addition in better intracellular calcium concentration and sperm kinematics.

Conclusion

QUE is recognized for its preventive effects against oxidative damage. This effect has been explored and validated; additionally, the findings of the present study substantiate this action, emphasizing improvements in various characteristics underlying sperm quality and fertilization capacity in buck spermatozoa for the first time. This study contributes to the understanding of enhancing semen quality by mitigating the adverse effects occurring during semen processing and cryopreservation.

Data availability

Data acquired during the study is included in supplementary files 1–5.

References

Tosti, E. & Ménézo, Y. Gamete activation: basic knowledge and clinical applications. Hum. Reprod. Update. 22, 420–439 (2016).

Gallo, A. & Tosti, E. Ion currents involved in gamete physiology. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 59, 261–270 (2015).

Kumar, A. et al. Quercetin in semen extender curtails reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and improves functional attributes of cryopreserved buck semen. Cryobiology 116, 104931 (2024).

Kumar, A., Saxena, A. & Anand, M. Subtle membrane changes in cryopreserved bull spermatozoa when modified temperature drop rates are used during the first phase of freezing. Cryo Lett. 45(4), 212–220 (2024).

Kumar, A., Saxena, A., Kumar, A. & Anand, M. Effect of cooling rates on cryopreserved Hariana bull spermatozoa. J. Anim. Res. 8, 149–154 (2018).

Amidi, F., Pazhohan, A., Shabani Nashtaei, M., Khodarahmian, M. & Nekoonam, S. The role of antioxidants in sperm freezing: a review. Cell. Tissue Bank. 17, 745–756 (2016).

Almeida, C. et al. Caspase signalling pathways in human spermatogenesis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 30, 487–495 (2013).

Selvaraju, S. et al. Current status of sperm functional genomics and its diagnostic potential of fertility in bovine (Bos taurus). Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 64, 484–501 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Comparative transcript profiling of gene expression of fresh and frozen–thawed bull sperm. Theriogenology 83, 504–511 (2014).

Li, Z., Lin, Q., Liu, R., Xiao, W. & Liu, W. Protective effects of ascorbate and catalase on human spermatozoa during cryopreservation. J. Androl. 31, 437–444 (2010).

Austin, C. R. The capacitation of the mammalian sperm. Nature 170, 326 (1952).

Chang, M. C. Fertilizing capacity of spermatozoa deposited into the fallopian tubes. Nature 168, 697–698 (1951).

De Jonge, C. Biological basis for human capacitation-revisited. Hum. Reprod. Update. 23, 289–299 (2017).

Puga Molina, L. C. et al. Molecular basis of human sperm capacitation. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 6, 72 (2018).

Publicover, S. J. Ca2 + signalling in the control of motility and guidance in mammalian sperm. Front. Biosci. Volume, 5623 (2008).

Lishko, P. V. et al. The control of male fertility by spermatozoan ion channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 453–475 (2012).

Lishko, P. V. & Mannowetz, N. CatSper: a unique calcium channel of the sperm flagellum. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2, 109–113 (2018).

Batool, I. et al. Quercetin in semen extender improves frozen-thawed spermatozoa quality and in-vivo fertility in crossbred Kamori goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 11, (2024).

Dalal, J., Kumar, A., Honparkhe, M., Singhal, S. & Singh, N. Comparison of three programmable freezing protocols for the cryopreservation of buffalo bull semen. Indian J. Anim. Reprod. 37, 54–55 (2016).

Dalal, J. et al. Low-density lipoproteins protect sperm during cryopreservation in buffalo: unravelling mechanism of action. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87, 1231–1244 (2020).

Mahfouz, R., Sharma, R., Sharma, D., Sabanegh, E. & Agarwal, A. Diagnostic value of the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in human seminal plasma. Fertil. Steril. 91, 805–811 (2009).

Bathgate, R. Antioxidant mechanisms and their benefit on post-thaw boar sperm quality. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 46, 23–25 (2011).

Lu, X. et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoTEMPO improves the post-thaw sperm quality. Cryobiology 80, 26–29 (2018).

Lasso Pirot, A., Fritz, K. I., Ashraf, Q. M., Mishra, O. P. & Delivoria-Papadopoulos, M. Effects of severe hypocapnia on expression of bax and bcl-2 proteins, DNA fragmentation, and membrane peroxidation products in cerebral cortical mitochondria of newborn piglets. Neonatology 91, 20–27 (2007).

Smith, R. et al. Increased sperm DNA damage in patients with varicocele: relationship with seminal oxidative stress. Hum. Reprod. 21, 986–993 (2005).

Thomson, L. K. et al. Cryopreservation-induced human sperm DNA damage is predominantly mediated by oxidative stress rather than apoptosis. Hum. Reprod. 24, 2061–2070 (2009).

Paasch, U. et al. Cryopreservation and thawing is associated with varying extent of activation of apoptotic machinery in subsets of ejaculated human spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 71, 1828–1837 (2004).

Duru, N. K., Morshedi, M., Schuffner, A. & Oehninger, S. Cryopreservation-thawing of fractionated human spermatozoa and plasma membrane translocation of phosphatidylserine. Fertil. Steril. 75, 263–268 (2001).

Dorado, J. et al. Relationship between conventional semen characteristics, sperm motility patterns and fertility of andalusian donkeys (Equus asinus). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 143, 64–71 (2013).

Ibanescu, I., Siuda, M. & Bollwein, H. Motile sperm subpopulations in bull semen using different clustering approaches–associations with flow cytometric sperm characteristics and fertility. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 215, 106329 (2020).

Seifi-Jamadi, A., Kohram, H., Shahneh, A. Z., Ansari, M. & Macías-García, B. Quercetin ameliorate motility in frozen-thawed Turkmen stallions sperm. J. Equine Veterinary Sci. 45, 73–77 (2016).

Rezaei, N., Mohammadi, M., Mohammadi, H., Khalatbari, A. & Zare, Z. Acrosome and chromatin integrity, oxidative stress, and expression of apoptosis-related genes in cryopreserved mouse epididymal spermatozoa treated with L-Carnitine. Cryobiology 95, 171–176 (2020).

Singh, P. et al. Effect of graphene oxide as cryoprotectant on post-thaw sperm functional and kinetic parameters of cross bred (HF X Sahiwal) and Murrah buffalo bulls. Cryobiology 106, 102–112 (2022).

Singh, P. et al. Sodium dodecyl sulphate, N-octyl β-D glucopyranoside and 4-methoxy phenyl β-D glucopyranoside effect on post-thaw sperm motion and viability traits of Murrah buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bulls. Cryobiology 107, 1–12 (2022).

Fernandez-Novo, A. et al. Effect of extender, storage time and temperature on kinetic parameters (CASA) on bull semen samples. Biology 10, 806 (2021).

Lizama, C., Alfaro, I., Reyes, J. G. & Moreno, R. D. Up-regulation of CD95 (Apo-1/Fas) is associated with spermatocyte apoptosis during the first round of spermatogenesis in the rat. Apoptosis 12, 499–512 (2007).

Janssen, H. L. A., Higuchi, H., Abdulkarim, A. & Gores, G. J. Hepatitis B virus enhances tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) cytotoxicity by increasing TRAIL-R1/death receptor 4 expression. J. Hepatol. 39, 414–420 (2003).

Guazzone, V. A., Jacobo, P., Theas, M. S. & Lustig, L. Cytokines and chemokines in testicular inflammation: a brief review. Microsc Res. Tech. 72, 620–628 (2009).

Kim, J. H. et al. Methyl jasmonate induces apoptosis through induction of Bax/Bcl-XS and activation of caspase-3 via ROS production in A549 cells. Oncol. Rep. 12, 1233–1238 (2004).

Mishra, D. P. & Shaha, C. Estrogen-induced spermatogenic cell apoptosis occurs via the mitochondrial pathway: role of superoxide and nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6181–6196 (2005).

Francavilla, S. et al. Fas expression correlates with human germ cell degeneration in meiotic and post-meiotic arrest of spermatogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8, 213–220 (2002).

Prochowska, S., Partyka, A. & Niżański, W. Expression of apoptosis-related genes in cat testicular tissue in relation to sperm morphology and Seasonality—A preliminary study. Animals 11, 489 (2021).

Martin, G., Sabido, O., Durand, P. & Levy, R. Cryopreservation induces an apoptosis-like mechanism in bull sperm. Biol. Reprod. 71, 28–37 (2004).

Duru, N. K., Morshedi, M. S., Schuffner, A. & Oehninger, S. Cryopreservation-thawing of fractionated human spermatozoa is associated with membrane phosphatidylserine externalization and not DNA fragmentation. Andrology 22, 646–651 (2001).

Grunewald, S. et al. Caspase activation in human spermatozoa in response to physiological and pathological stimuli. Fertil. Steril. 83(Suppl 1), 1106–1112 (2005).

Rosado, J. A. et al. Early caspase-3 activation independent of apoptosis is required for cellular function. J. Cell. Physiol. 209, 142–152 (2006).

Kumar, A., Saxena, A. & Anand, M. Evaluation of acrosomal integrity and viability in bull spermatozoa: comparison of cytochemical and fluorescent techniques. Int. J. Livest. Res. 1 (2019).

Hwang, J. Y. et al. Dual sensing of physiologic pH and calcium by EFCAB9 regulates sperm motility. Cell 177, 1480–1494e19 (2019).

Eisenbach, M. & Giojalas, L. C. Sperm guidance in mammals - an unpaved road to the egg. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 276–285 (2006).

Strünker, T. et al. The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca2 + influx in human sperm. Nature 471, 382–386 (2011).

Qi, H. et al. All four CatSper ion channel proteins are required for male fertility and sperm cell hyperactivated motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 1219–1223 (2007).

Askari Jahromi, M. et al. Evaluating the effects of Escanbil (Calligonum) extract on the expression level of Catsper gene variants and sperm motility in aging male mice. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 12, 459–466 (2014).

Singh, A. P. & Rajender, S. CatSper channel, sperm function and male fertility. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 30, 28–38 (2015).

Alipour, F. et al. Assessment of sperm morphology, chromatin integrity, and catSper genes expression in hypothyroid mice. Acta Biol. Hung. 69, 244–258 (2018).

Sun, X. H. et al. The Catsper channel and its roles in male fertility: a systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 15, 65 (2017).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. K., J.K. P. and N. K. conceived the experiment. R. D. and A. K. were responsible for the collection, processing, cryopreservation, and DNA fragmentation analysis of sperm. A. K. conducted sperm kinetics evaluation using CASA. The flowcytometric evaluation of sperm functions was conducted by M. (A) and S. V. , Aj. K. and A. (B) conducted gene expression studies of Apoptotic regulatory genes, while S. V. conducted gene expression analysis of CatSper channel gene. J. T. oversaw data analysis, statistical design, S.S. prepared table and V. Y. performed proof reading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Present research work was performed at Bihar Veterinary College, Bihar Animal Sciences University, Patna, and Department of Veterinary Physiology, DUVASU The study was conducted in compliance with the directions in addition to the approval of the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of Bihar Animal Sciences University (IAEC/BVC/2023/02).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Prasad, J.K., Kumar, N. et al. Quercetin modulates transcription of the apoptotic and CatSper genes and optimises post thaw viability and kinematics of buck spermatozoa. Sci Rep 15, 22818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88525-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88525-z