Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a prevalent and highly fatal primary malignant brain tumor. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification plays a critical role in the development of brain tumor. WTAP and ZC3H13 have been identified across various species. Immune contexture, which includes the tumor microenvironment (TME), plays a significant role in cancer progression and treatment. This study aimed to explore the potential impact between WTAP and ZC3H13 on the immunological characteristics of GBM. We utilized data from TCGA-GBM, GEO and CGGA datasets to obtain platform and probe data. Patients with GBM were stratified into two clusters based on the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 using consensus clustering approach. Immune infiltration within the tumor microenvironment was assessed using ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT and ssGSEA methodologies. Functional disparities were determined through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) were also analyzed. Co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to identify genes associated with WTAP/ZC3H13 and immunity. Validation was performed using GEO and CGGA datasets. Our analysis revealed that cluster1 exhibited higher WTAP expression but lower ZC3H13 expression compared to cluster2. Cluster1 showed higher levels of immune infiltration and TMB compared to cluster2. WGCNA identified 15 genes closely associated with WTAP/ZC3H13 expression and immune scores, notably CTLA4, CD27, ICOS, and LAG3. Our results suggested that WTAP and ZC3H13 influence on immune contexture of GBM, providing new insights into tumor immunity in GBM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and lethal brain cancer. The survival rate for patients diagnosed with WHO grade IV glioma is extremely low, with a 5-year survival rate of only 5.5%1.The high infiltrative nature of GBM, combined with genetic heterogeneity, complicates therapeutic strategies2. Immunotherapy has emerged as an effective approach for many cancers, but its efficacy varies among patients3,4. The future of immunotherapy likely depends on identifying biomarkers to guide personalized treatments. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common RNA modification in mammals, involved in regulating RNA processing such as degradation, nuclear export and translation5,6. Dysfunctional m6A modification has been associated with various types of cancers7,8,9. In the context of tumors, m6A RNA methylation can act as a double-edged sword, with its impact dependent on the interaction of “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers.”10. In the context of tumors, m6A RNA methylation serves as a double-edged sword, with its impact dependent on the interplay of the three aforementioned factors. Current studies suggest that dysregulated m6A regulators may influence cancer growth, and targeting m6A modification could potentially enhance cancer therapy when combined with immunotherapy or chemotherapy11,12. The “writers” of m6A RNA methylation are a group of methyltransferases, which can be divided into two subcomplexes: the m6A-METTL complex (MAC) that includes METTL3 and METTL14, and the m6A-METTL associated complex (MACOM) that consists of Wilms tumor 1 associated protein (WTAP), Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13 (ZC3H13), RNA binding motif protein 15/15B (RBM1/15B), and vir-like m6A methyltransferase-associated protein (VIRMA). WTAP and ZC3H13 play roles in the nuclear localization of the MAC. Research has shown that m6A RNA methylation is drastically reduced in the absence of either WTAP or ZC3H1313.

WTAP has been shown to modulate immune cells and suppress tumorigenesis by reducing m6A modification of WTAP through Wnt signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer14. ZC3H13 has been identified as a potential tumor suppressor gene, inhibiting the proliferation of colon cancer cells via RAS-ERK pathway15. Additionally, ZC3H13 has been associated with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) response and the tumor immune microenvironment (TME) in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma16, as well as being linked to prognosis and immune infiltrates in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma17. Although both WTAP and ZC3H13 play important roles in cancer, no studies have yet investigated their combined effects in cancer.

To better understand the roles of WTAP and ZC3H13 in tumor immunity, we conducted an analysis using transcriptome profiling data from TCGA-GBM, CGGA, and GEO databases. Patients were classified into two clusters based on the expression levels of WTAP and ZC3H13. Bioinformatic analyses were performed to compare clinical characteristics, immune infiltration, immune checkpoint expression, mutation profiles, and biological pathways between the two clusters. The results revealed that cluster 1 had higher expression of WTAP compared to ZC3H13, alongside increased immune infiltration, checkpoint inhibitor expression, and tumor mutation burden (TMB)1. This suggests that cluster 1 may exhibit a more favorable response to immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

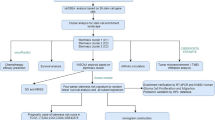

Data collection and analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from glioblastoma tissue samples were retrieved from several public databases: the TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) through the UCSC Xena website (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA, http://www.cgga.org.cn/). The CGGA data provided comprehensive clinical information, including age, gender, tumor grade, radiotherapy status, chemotherapy status and MGMTp methylation status. The TCGA-GBM dataset consisted of 173 samples. Somatic mutation data were accessed from the Genomic Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) using the package TCGA- Biolinks in R18. Additionally, we used the complex-heat map package to visualize a waterfall plot of mutations in GBM19. The immune characteristics of GBM patients were analyzed using data from GSE108474, GSE50161 and CGGA datasets20. Since these databases are publicly available, no local ethics committee approval was required.

Immune infiltration analysis

The ESTIMATE algorithm was used to estimate the stromal and immune cell content in tumor tissues. This allowed for the calculation of stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score, and tumor purity, utilizing the R package. The ESTIMATE algorithm evaluates the proportions of stromal and immune cells in tumor samples based on gene expression signatures. CIBERSORT (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/) was employed to compute cell composition from gene expression profiles. The proportion of 22 immune cell types in the high- and low-expression clusters were compared and visualized using the R package “vioplot”21. Infiltration levels of 28 immune cell types in the clusters were calculated using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) with the R package GSVA22.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the “clusterProfiler” package in R, along with the c2.cp.kegg.v7.5.1.entrez.gmt dataset, to identify functional difference between clusters. The Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB) was used for the analysis (https://www.gseamsigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/ index.jsp)23. Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 package on HTSeq-Counts data, with threshold values of |log2FoldChange | >1 and an adjusted P value < 0.05.

Differential expressed genes (DEG) analysis

Differential expression profiling of the clusters was conducted using DESeq2 package in R on the HTSeq-Counts data, applying threshold values of |log2FoldChange | >1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed on differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using the WGCNA package in R24. Nine modules were identified, and the correlation between clusters and the ESTIMATE score, immune score, stromal score, and tumor purity was calculated. Hub genes within these modules were selected based on gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM) criteria. Genes with |GS| > 0.2 and |MM| > 0.8 were chosen as hub genes.

Functional enrichment analysis

Functional enrichment analysis was performed through Gene ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gens and Genomes (KEGG) analysis using the “clusterProfiler” package in R. A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING database. Spearman’s correlation analysis of gene–gene, gene–ESTIMATE, and gene–ssGSEA relationships was conducted using the “corrplot” package R25.

Cell culture

Human glioblastoma U87MG cells were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium-High glucose (DMEM, D5796, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sijiqing, Hangzhou, China), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 g/ml streptomycin, and incubated at 37℃ in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2. U87MG cells were passaged 2–3 times per week.

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

For gene knockdown, DNA fragments encoding hairpin precursors for WTAP were synthesized and inserted into the shRNA expression vector GV248. For overexpression, the full-length open reading frame (ORF) of human ZC3H13 was synthesized and cloned into pIRES2-EGFP. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine2000 Reagent (Invitrogen Preservation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Stably transfected cells were selected under G418 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) or Puromycin (Sigma). Cell clones were obtained via the limited diluted method.

Specimen collection and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Ten GBM tissue samples and adjacent normal tissues were collected from the First Hospital of Jiujiang University. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical School of Jiujiang University (approval number: JJU202400017) and all experiments were conducted according to relevant guidelines and regulations. In addition, specimens were obtained from Human glioblastoma U87MG cells and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. Tissues and cells were lysed in TRIzol lysis solution (cat no. 15596-018; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol and dissolved in nuclease-free water. For the detection of WTAP, ZC3H13, CD27, CD70, CD80, CD86, ICOS, CTLA4 and LAG3 expression, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript II 1st strand cDNA Synthesis kit (cat no. 6210 A; Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) and qPCR was performed with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (cat no. DRR420A, Takara) using an ABI 7900 Prism Real-Time PCR system (model no. 7900HT; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). 18s rRNA was used as an internal control. The amplification conditions for WTAP and ZC3H13 were: Polymerase activation for 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The threshold cycle (Cq) value of PCR amplification was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method.

Western blot analysis

Total lysates from different treatments of U87MG cells were prepared using 5 x SDS lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (P1006, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Protein concentration was measured using the BSA protein assay (P0398S, Beyotime Biotechnology). Forty micrograms of protein were fractionated on a 12% SDS-PAGE, transfered to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were immunoblotted with the primary antibodies: WTAP (A04296-2, Boster Biotech, Wuhan, China), CD27 (A01148-2, Boster Biotech), CD70 (A02853-2, Boster Biotech), CD80 (A00196-3, Boster Biotech), CD86(BM4121, Boster Biotech), ICOS (A00291-2, Boster Biotech), CTLA4 (A00020-1, Boster Biotech), LAG3 (M02869-2, Boster Biotech), Beta-actin (BM3873, Boster Biotech). Beta-actin was probed as a loading control. Then membrances were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (BM3898, Boster Biotech), Western blot analysis was performed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System ((LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS and R software, with Spearman’s coefficient used to assess relationships. Clinical characteristics between clusters were compared using a two-tailed Student’s t-test and Chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate clinical factors influencing cluster assignment. Statistical significance was considered at p-values < 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Immune-related m6A regulators analysis

We first analyzed the impact of m6A regulators on the immune micro environment in GBM patients. Among 20 identified m6A regulators, we focused on the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 using RNA-seq data from TCGA-GBM. The results showed that 20 m6A regulators were examined the correlation between their expression and ESTIMATE (Fig. 1A). WTAP expression was higher in tumor tissues than in normal tissues, whereas ZC3H13 showed lower expression in tumors compared to normal tissues (Fig. 1B, C). Using consensus clustering, we grouped the 144 GBM samples into two clusters based on the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 (Fig. S1). The heatmap visualization demonstrated that cluster 1 exhibited high WTAP expression and low ZC3H13 expression, with a significant inverse correlation between the two(Fig. 1D). Furthermore, WTAP and ZC3H13 play roles in the nuclear localization of the MAC. Spearman’s analysis revealed an inverse correlation in the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 between the two clusters (R = − 0.305, P = 2.18 × 10− 5, Fig. 1E). In addition, MACOM includes WTAP, HAKAI, RBM15, RBM15B, VIRMA and ZC3H13, forms a stable functional unit, but the expression of HAKAI, RBM15, RBM15B and VIRMA were high in tumor(Fig. S2).

The relationship of m6A regulators, immune score and clustering of TCGA-GBM patients according to the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13. The correlation between m6A regulators and results of ESTIMATE (A). The expression of WTAP and ZC3H13in GBM (n = 144) and the corresponding normal tissue (n = 10), respectively (B and C). The heatmap of two clusters (group1 = 79, group2 = 65) according to the expression WTAP and ZC3H13 in TCGA-GBM (D).The association between the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 (E). The data are mean ± standard deviation. ** P < 0.01 compared with the corresponding control values.

Clinical characteristics

Using TCGA, GEO, and CGGA datasets, we analyzed the clinical characteristics of the two clusters. Although no survival data was available from GEO, a survival analysis using TCGA data did not show significant differences in prognosis between clusters. However, a notable survival difference was observed in the CGGA dataset (Fig. S3A and B). The clinical characteristics was analyzed (Table S1).

Immune characteristics and pathways

GSEA revealed significant enrichment of immune-related pathways in both clusters. These included pathways related to adaptive immune response, immune system regulation, and the positive regulation of immune processes (Fig. 2A and Table S2). To further investigate the immunological differences between cluster1 and cluster2, we utilized ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT, and ssGSEA. The result showed that the stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores of cluster1 were higher than those of cluster2, while the tumor purity of cluster2 was greater than that of cluster1(Fig. 2B). Cluster 1 exhibited higher levels of CD4 + T cells, M2 macrophages, and other immune cell types, indicating a more robust immune response (Fig. 2C). The ssGSEA analysis revealed that the expression of 22 immune cell subtypes, including activated CD4 T cells, activated CD8 T cells and activated dendritic cells, was higher in cluster 1 compare to cluster2. Furthermore, the analysis highlighted 28 immune cell subtypes between the two clusters (Fig. 2D and Fig. S4). In summary, the results suggest that immune infilitraton is higher in cluster 1 than in cluster 2.

The immune characteristics between two clusters. The functional enrichment of two clusters (A). The proportion of stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity (B). The difference of immune cells and expression of immune cells between two clusters (C). ssGSEA analysis ‘between two clusters (D). The number of cluster1 is 79, and cluster2 is 65. The data are mean ± standard deviation (ns, no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding control values).

Immunotherapy analysis

To assess the sensitivity of immunotherapy in GBM patients, we identified immunotherapy targets in the two clusters. Cluster 1 showed higher expression levels of immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD1, PDL2, CTLA4, CD86, LAG3 and ICOS) compared to cluster 2, indicating that cluster 1 may be more responsive to immunotherapy (Fig. 3A–D). These findings suggest that the response to immunotherapy in cluster1 may be better than in cluster2.

The immune checkpoint gene of GBM between two clusters. PD1 related immune checkpoint gene (A). CTA4 related immune checkpoint gene (B). Other immune checkpoint gene (C). Agonists of T cell activation gene (D). The data are mean ± standard deviation (ns, no significance, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding control values).

Genetic mutation, co-expression and immune infiltration

Genetic mutations can influence the effectiveness of immunotherapy. Therefore, we examined the mutations in the two clusters. The mutation profiles of the two clusters are shown in Fig. 4A and B. Cluster 1 also exhibited a higher TMB compared to cluster 2. Notably, mutations in genes such as MLH1, MSH2, and PMS2 were more frequent in cluster 1 (Fig. 4C, D). These results suggest that the cluster 1 may respond more favorably to immune checkpoint blockade therapies, and TMB could be a potential factor in predicting response to immune checkpoint immunotherapy26. A total of 144DEGs were identified, with 79 upregulated and 65 downregulated gene between the two clusters. The volcano plot of these DEGs was shown in Fig. S5A. Using WGCNA, we explored the correlation between m6A modification and immunity across modules and traits. A strong correlation between m6A (R = 0.59, P = 9e-15) and immunity (R = 0.66, P = 2.9e-28) was observed in MEturquoise module(Fig. 5A, Fig. S5B and C). Subsequently, 15 hub genes (CTLA4, CD27, LAG3, ICOS, CCL13, CCL20, CCL7, CSF2, CSF3,CXCL13, CXCL3, CXCL5, IL2RA, MMP7 and CXCL8) were identified from the MEturquoise module based on MM > 0.7 and GS > 0.25 (Fig. 5B, Fig. S5D). The heatmap of these 15 hub genes revealed expression differences between the two tumor clusters (Fig. 5C).

The mutation between two clusters. The mutational landscape of cluster 1 and cluster 2, respectively (A and B). The tumor mutation burden (TMB) etween two clusters (C). The association of POLE proofreading domain with mismatch repairing of gene mutation between two clusters (D). The number of cluster1 is 79, and cluster2 is 65. The data are mean ± standard deviation (**P < 0.01 compared with the corresponding control values).

The relationship of the two clusters between immunity in the WGCNA. The different expressed genes were analyzed by volcano plot (A). The soft powers were analyzed by network topology (B). Gene dendrogram and module colors (C). The module associated with both clustering and eigengenes and cluster ESTIMATE results by heatmap (D). The scatter plot of module eigengenes in the blue module (E). The number of cluster1 is 79, and cluster2 is 65.

Functional enrichment of hub genes and correlation with immune infiltration

The GO enrichment analysis revealed that the 15 hub genes were predominantly involved in the positive regulation of immune system (Fig. 6A). The gene associations and PPI analysis were also examined (Fig. 6B-C). The relationship between gene expression and immune infiltration was found to be significant through ESTIMATE and ssGSEA analysis (Fig. 6D-E).

The analysis of 15 hub genes. The hub gene was analyzed by GO enrichment analysis (A). The hub gene was attained by PPI network (B). The association between the hub genes (C). The association of hub genes between ESTIMATE (D). The ssGSEA was analyzed the correlation of hub genes and expression of immune cells (E).

GEO validation of immune characteristics analysis

For glioblastoma samples from GSE108474 and GSE50161, batch correction was performed, and patients were divided into two clusters using the same method as TCGA data. This showed similar expression patterns of WTAP and ZC3H13 in the two clusters (Fig. 7A). Spearman’s correlation coefficient for WTAP and ZC3H13 was R = − 0.023 (Fig. 7B). Evaluation of the expression of immunomodulatory target genes and immune infiltration (using ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT and ssGSEA) revealed that cluster 1 exhibited a more active immune response compared to cluster2 (Fig. 7C-F).

The validation of immune character between two clusters in GEO data. The headmap of expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 in two clusters (A). The association between WTAP and ZC3H13 in GSE108474 and GSE50161 (B). The correlation of stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity in two clusters (C).The targets of immunomodulatory (D). The proportion of immune cells (E) and expression of immune cells (F) between two clusters. The number of cluster1 is 79, and cluster2 is 65. The data are mean ± standard deviation (ns, no significance, *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding control values).

CGGA validation of immune characteristics analysis

Similarly, 328 glioblastoma samples from the CGGA dataset were divided into two clusters using the same method as TCGA data, showing similar expression patterns of WTAP and ZC3H13 (Fig. 8A). Spearman’s correlation coefficient for WTAP and ZC3H13 was R = − 0.243 (p < 0.05, Fig. 8B). Analysis of immunomodulatory targets genes and immune infiltration (ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT and ssGSEA) showed that cluster 1 demonstrated potentially more active immune system responses compared to cluster 2 (Fig. 8C-F).

The validation of immune character between two clusters in CGGA data. The headmap of expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 in two clusters (A). The association between WTAP and ZC3H13 in CGGA data (B). The correlation of stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity in two clusters (C).The targets of immunomodulatory (D). The proportion of immune cells (E) and expression of immune cells (F) between two clusters. The number of cluster1 is 446, and cluster2 is 572. The data are mean ± standard deviation (ns, no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding control values).

Verification of gene expression levels

To study the expression patterns of WTAP, ZC3H13, CD27, CD70, CD80, CD86, ICOS, CTLA4 and LAG3 in tissues and human glioblastoma U87MG cells, the expression levels were tested. WTAP expression significantly increased (4.32 ± 0.49 fold) compared to adjacent normal tissues, while ZC3H13 expression was significantly reduced (3.16 ± 0.50 fold) in GBM tissues (Fig. 9A). The silencing of WTAP using FAM-siRNA primers in U87MG cells resulted in a 55% reduction in expression (Fig. 9B -C). The expression levels of CD27, CD70, CD80, CD86, ICOS, CTLA4, and LAG3 in siRNA WTAP and overexpressed ZC3H13 were demonstrated in Fig. 9D-F.

Relative expression of genes expression in GBM tissues. Expression levels of WTAP and ZC3H13 genes were compared with those of the control group on GBM tissues, 10 GBM and adjacent tissues, respectively (A). The expression levels of siRNA WTAP and overexpression ZC3H13 genes (B and C). The expression levels of CD27, CD70, CD80, CD86, ICOS, CTLA4, and LAG3 in siRNA WTAP and overexpression ZC3H13 were demonstrated in Fig. 9D and F, respectively. The result were determined by qRT-PCR. The data are mean ± standard deviation of six replicate experiments. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding control values.

Discussion

The catalytic subunit of the m6A writer complex is formed by MACOM (comprising WTAP, VIRMA, ZC3H13, HAKAI, and RBM15/RBM15B) forms a stable functional unit, regulating m6A writer activity and selective methylation of mRNAs. ZC3H13 played a critical role in anchoring WTAP in the nucleus to facilitate m6A methylation27. WTAP was found to be upregulated in glioblastoma, promoting metastasis and invasion, thus acting as a tumor promoter28. WTAP has been implicated in various cancer types, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma29, where it has been linked to T-cell-inflamed gene expression profiles and immune checkpoints14. However, its relationship with immunotherapy response in glioblastoma remains unexplored. Conversely, ZC3H13’s low expression is linked to suppressed proliferation and invasion in colorectal cancer, suggesting a tumor suppressor role30. ZC3H13 may also act as a tumor suppressor in glioblastoma31. However, there is no report on the role of their interaction in cancer. In this study, we found consistent expression patterns of WTAP and ZC3H13 in GBM, as well as a negative correlation between their expression levels, indicating a potential interaction through m6A modification. The expression of HAKAI, VIRMA and RBM15/RBM15B was also found to be high in tumors (Figure S4). Furthermore, analysis of multiple datasets revealed a negative correlation between WTAP and ZC3H13 expression and immune score, which may impact immune infiltration and response to immunotherapy in GBM. Subgroup analysis identified two distinct clusters of glioblastoma patients based on WTAP and ZC3H13.

To further investigate the function of these clusters, GSEA analysis revealed enrichment of immune-related pathways in both clusters, suggesting a connection to immune responses. Immune-related pathways such as adaptive immune response and immune system regulation were enriched in both clusters. The immune characteristics were evaluated using ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT, and ssGSEA analyses. The ESTIMATE analysis, based on TCGA, GSE108474, GSE50161 and CGGA data, revealed higher stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores in cluster1 compared to cluster 2. This suggests a dynamic tumor immune microenvironment in cluster 1 and implies that cluster 1 may exhibit more active in immune response than cluster 2. The CIBERSORT analysis demonstrated a significantly high proportion of CD4 T cells, macrophages, and mast cells in cluster 1 compared to cluster 2. Additionally, ssGSEA analysis showed significantly higher expression of 22 immune cell subtypes in cluster 1, including CD4 and CD8 Tcells, dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophil cells, B cells, macrophages cells, mast cells, myeloid-derived cells, mast cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC cells), monocyte cells, natural killer (NK) cells, regulatory T cells, T helper cells (CD4), and natural killer T (NKT) cells, compared to Cluster 2. Furthermore, the proliferation of CD4/CD8 + T cells has been linked to improved survival in GBM. DCs are considered to have varied functional states that influence anti-tumor T cell immunity32. Conventional type 1 dendritic cells can be recruited by NK cells into the tumor microenvironment33. NK cells have been identified as immune regulatory cells with cytotoxic potential in anti-tumor response against GBM34. Stimulating NKT cells has shown promise as a therapeutic strategy for patients with anti-PD-1–resistant cancer, and NKT cells are pivotal in anti-tumor immunity35. NKT cells may serve as a potential immunotherapy target for glioblastoma patients by focusing on CD1d36. Macrophages differentiate into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. CIBERSORT and ssGSEA analyses showed a higher proportion of M1 macrophages and increased macrophage expression in cluster1 compared to cluster2, indicating that cluster1 could more readily establish an anti-tumor microenvironment and suggesting superior “immune competence” in cluster1. Therefore, patients in cluster1 may be more likely to benefit from immunotherapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including programmed cell death 1 (PD1), and its ligand PDL1 and PDL2, as well as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) and its ligands (CD80 and CD86), are well-established targets for immunotherapy37. Emerging immune checkpoints such as lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3)38, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3)39, and T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) are also significant co-inhibitory receptor targets40. The analysis revealed significantly higher expression of these targets in Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2.

TMB may influence the response to immunotherapy41. The analysis indicated that the TMB in cluster1 was higher than cluster2. Additionally, the expression of mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) and POLE was higher in cluster1, suggesting that cluster1 may exhibit a better response to immunotherapy.

To assess the relationship between WTAP/ ZC3H13 and immune score, WGCNA was performed. Fifteen hub genes, including CTLA4, CD27, LAG3 and ICOS were identified. CTLA4, CD27, LAG3 and ICOS were obtained. These genes are known to mediate T-cell exhaustion42, which may occur in cluster 1, suggesting that this cluster might have a better response to immunotherapy. RT-qPCR validation of WTAP, ZC3H13, CD27, CD70, CD80, CD86, ICOS, CTLA4 and LAG3 expression in 10 GBM and adjacent tissues showed that cluster1 may represent “hot tumors”, while cluster2 may represent “cold tumors”, with cluster1 playing a key role in the immune activity of “hot tumors” in GBM.

Although the relationship between WTAP, ZC3H13 and immunity was thoroughly analyzed, further validation using glioblastoma samples of GSE108474, GSE50161 and CGGA showed similar, though not identical, results compared to TCGA. It was noted that the number of pure glioblastoma samples was small in GSE108474 and GSE50161, and these were retrospective studies. Therefore, prospective studies are recommended to avoid potential bias in the analysis. Additionally, direct analysis of the protein level of WTAP and ZC3H13 is need to demonstrate their role in anti-tumor immunity, and further experimental studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the effects of WTAP and ZC3H13.

Conclusion

This study analyzes the expression of WTAP and ZC3H13 in various datasets, showing high expression of WTAP in cluster 1 and low expression of ZC3H13. Cluster 1 exhibited higher levels of immune checkpoint targets, immune cell infiltration, TMB, and dMMR-MSI-H, suggesting that WTAP and ZC3H13 may provide novel insights into m6A modification and tumor immunity.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- TMB:

-

Tumor mutation burden

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- WTAP:

-

Wilms tumor 1- associated protein

- ZC3H13:

-

Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13

- ICB:

-

Immune checkpoint blockade

- TME:

-

Tumor immune microenvironment

- UCSC:

-

University of California, Santa Cruz database

- CGGA:

-

Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- ESTIMATE:

-

Estimation of stromal and immune cells via expression data

- ssGSEA:

-

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gens and Genomes

- PPI:

-

Protein–protein interaction

- RTqPCR:

-

Reverse transcriptionquantitative polymerase chain reaction

- NK:

-

Natural killer

- PD1:

-

Programmed cell death 1

- CTLA4:

-

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4

- LAG-3:

-

Lymphocyte activation gene-3

- TIM-3:

-

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

- TIGIT:

-

T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain

References

Chen, C. H. et al. Suppression of tumor growth via IGFBP3 depletion as a potential treatment in glioma. J. Neurosurg. 132, 168–179 (2019).

Cui, X. et al. Dissecting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments in Glioblastoma-on-a-Chip for optimized PD-1 immunotherapy. Elife 9, e52253 (2020).

Lyu, N., Yi, J. Z. & Zhao, M. Immunotherapy in older patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 162, 76–98 (2022).

Cavalluzzo, B. et al. Novel molecular targets for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 14, 140 (2021).

Van, V. E. C. N. et al. N6-methyladenosine promotes TNF mRNA degradation in CD4 + T lymphocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 4 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in DNA damage response and cancer radiotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2024).

Gao, Z., Long, Y., Wu, Y., Pu, Y. & Xue, F. LncRNA LINC02253 activates KRT18/MAPK/ERK pathway by mediating N 6-methyladenosine modification of KRT18 mRNA in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis 43, 419–429 (2022).

Gao, C. et al. Analysis of the expression patterns and clinical relevance of m6A regulators in 33 cancer types. Future Oncol. 18, 565–577 (2022).

Huang, H., Weng, H. & Chen, J. m6A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: roles and therapeutic implications in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 37, 270–288 (2020).

Fang, Z. et al. Role of m6A writers, erasers and readers in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 1–20 (2022).

Shen, Y., Wang, S. & Wu, Y. A novel m6A-related LncRNA signature for predicting prognosis, chemotherapy and immunotherapy response in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cells 11, 2399 (2022).

Gu, C. et al. RNA m 6 a modification in cancers: Molecular mechanisms and potential clinical applications. Innovation 1, 11 (2020).

Paramasivam, A., George, R. K. & Priyadharsini, J. Genomic and transcriptomic alterations in m6A regulatory genes are associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 11 7, 3688–3697 (2021).

Xu, J. -l. Wilms tumor 1-associated protein expression is linked to a T-cell-inflamed phenotype in pancreatic cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 68, 831–840 (2023).

Lin, Y., Zhang, B. & Chen, Z. circRERE regulates the expression of GBX2 through miR-1299 and ZC3H13/N6-methyladenosine (m6A) to Promote Growth and Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma cells. J. Biosci. 47, 52 (2022).

Lu, M. et al. Novel immune-related ferroptosis signature in esophageal cancer: an informatics exploration of biological processes related to the TMEM161B-AS1/hsa-miR-27a-3p/GCH1 regulatory network. Front. Genet. 13, 829384 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Identification of m6A methyltransferase-related genes predicts prognosis and immune infiltrates in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Transl Med. 9 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. Hypermethylation of LATS2 promoter and its prognostic value in IDH-mutated low-grade gliomas. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 586581 (2020).

Lin, A. et al. Genomic and immunological profiles of small-cell lung cancer between East asians and caucasian. Cancer Cell. Int. 22, 1–16 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. A novel six-mRNA signature predicts survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Front. Genet. 12, 634116 (2021).

Zhong, Q. Y. et al. A gene expression-based study on immune cell subtypes and glioma prognosis. BMC cancer. 19, 1–10 (2019).

Zhu, Y., Feng, S., Song, Z., Wang, Z. & Chen, G. Identification of immunological characteristics and immune subtypes based on single-sample gene set enrichment analysis algorithm in lower-grade glioma. Front. Genet. 13, 894865 (2022).

Duan, Y., Liu, Y., Xu, Y. & Zhou, C. Bioinformatics analysis identifies key genes in recurrent implantation failure based on immune infiltration. Reprod. Sci. 30, 952–965 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Diabetic kidney disease-predisposing proinflammatory and profibrotic genes identified by weighted gene co‐expression network analysis (WGCNA). J. Cell. Biochem. 123, 481–492 (2022).

Bai, J., Pu, X., Zhang, Y. & Dai, E. Renal tubular gene biomarkers identification based on immune infiltrates in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Ren. Fail. 44, 966–986 (2022).

Haibo et al. Successful response to the combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma with high tumour mutational burden and PD-L1 expression: a case report. Bmc Cancer. 18, 1105 (2018).

Wen, J., Lv, R., Ma, H., Shen, H. & Diao, J. Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA m 6 a methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell Self-Renewal. Mol. Cell. 69, 1028–1038e1026 (2018).

Li, Z. X. et al. WTAP-mediated m6A modification of lncRNA DIAPH1-AS1 enhances its stability to facilitate nasopharyngeal carcinoma growth and metastasis. Cell. Death Differ. 29, 1137–1151 (2022).

Fan, Y. et al. Role of WTAP in cancer: from mechanisms to the therapeutic potential. Biomolecules 12, 1224 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Identification and validation of the N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation regulator ZC3H13 as a novel prognostic marker and potential target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Med. Sci. 19, 618 (2022).

Li, P., Richard, H. T., Zhu, K., Li, L. & Huang, S. The roles and regulation of m6A modification in glioblastoma stem cells and tumorigenesis. Biomedicines 10, 969 (2022).

Duong, E. et al. Type I interferon activates MHC class I-dressed CD11b + conventional dendritic cells to promote protective anti-tumor CD8 + T cell immunity. Immunity 55, 308–323 (2022). e309.

Reschke, R., Olson, D. J. & Leveraging, S. T. I. N. G. Batf3 dendritic cells, CXCR3 ligands, and other components related to innate immunity to induce a hot tumor microenvironment that is responsive to immunotherapy. Cancers 14, 2458 (2022).

Miller, J. et al. (BMJ Specialist Journals, (2020).

Bae, E. A. et al. Activation of NKT cells in an anti-PD-1–resistant tumor model enhances antitumor immunity by reinvigorating exhausted CD8 T cells. Cancer Res. 78, 5315–5326 (2018).

Hara, A. et al. CD1d expression in glioblastoma is a promising target for NKT cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 70, 1239–1254 (2021).

Sharafi, F. et al. A comprehensive review about the utilization of immune checkpoint inhibitors and combination therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: an updated review. Cancer Cell. Int. 22, 1–13 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Analysis of the immune checkpoint lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3) in endometrial cancer: an emerging target for immunotherapy. Pathol. Res. Pract. 236, 153990 (2022).

Mohsenzadegan, M. et al. The prospect of targeting T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing‐3 in renal cell carcinoma immunotherapy. Scand. J. Immunol. 96, e13197 (2022).

Tian, X., Ning, Q., Yu, J. & Tang, S. T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain in cancer immunotherapy: a focus on tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells. Mol. Immunol. 147, 62–70 (2022).

Anagnostou, V., Bardelli, A., Chan, T. A. & Turajlic, S. The status of tumor mutational burden and immunotherapy. Nat. Cancer. 3, 652–656 (2022).

Bjoern, J. et al. Influence of ipilimumab on expanded tumour derived T cells from patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget 8, 27062 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank UCSC xena website (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA, http://www.cgga.org.cn/), and the Genomic Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) .

Funding

This work was funded by the grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502843, 81360447), Jiangxi Natural Science Foundation Project (20202BAB206067, 20232BAB206141), Jiujiang base and talent plan-high level scientific and technological innovation talent project (S2020QNZZ011, S2024ZDYFN0023), Future project of Jiujiang administration of traditional Chinese medicine (2021b697), Special Research Project of Jiangxi Cognitive Science and Interdisciplinary Research Center (RZYB202206), Science and Technology Plan Project of Jiangxi Provincial Health Commission (SKJP220225877, 202311158). Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (202311843003, S202411843047), Department of Science and Technology of Hubei Province with the Project (2022BCE045), Talent Introduction Projects of Hubei Polytechnic University (22xjz16R). Key research and development project of Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province (S2024ZDYFN0014 and S2024ZDYF0023), Xuncheng Talents project in Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province (JJXC2023071).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liyun Gao provided conception. Jiaxin Gao collected resources of the study. Jiayin He used the methodology. Wenyan Fan reply software. Xiangxin Che had a supervision. Xin Wang Wrote the original draft. Tao Wang and Chunhua Han reviewed &edited the articles.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, L., Gao, J., He, J. et al. Identification of m6A methyltransferase-related WTAP and ZC3H13 predicts immune infiltrates in glioblastoma. Sci Rep 15, 4412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88671-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88671-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The mechanistic role of Wilms tumor 1-associated protein in cancer pathogenesis, immunity, immunotherapy, and therapy resistance

Investigational New Drugs (2026)

-

The m6A modification in cancer: roles, implications, and its potential in therapy

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)