Abstract

Previous studies investigating the correlation between mode of delivery and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have yielded inconsistent results. This study aims to investigate the association between mode of delivery and PTSD in a cohort of Chinese women with a high rate of cesarean section (CS). We conducted a prospective cohort study in China between October 2019 and June 2021. Women aged 20–45 years who give birth at The Seventh Hospital of the Southern Medical University during the study period were enrolled. PTSD was assessed by the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version at 42 days postpartum. We examined the independent association between mode of birth and PTSD by log-binomial regression analysis. A total of 759/800 (94.88%) women completed questionnaire. The prevalence of postpartum PTSD was 12.12% in included women, 8.18% in women with vaginal delivery (VD), 17.55% in women with CS. After adjusting for confounding factors, it was found that women with elective CS (RR = 1.70, 95%CI, 1.03 to 2.87) and emergency CS (RR = 1.95, 95%CI, 1.08 to 3.83) had an increased risk of developing postpartum PTSD compared with women with VD. CS is identified as an independent risk factor for PTSD in a cohort of Chinese women with a high prevalence of CS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although childbirth is normally viewed as a pleasant life event, the rapid psychophysiological changes during childbirth may render it to be a stress-inducing experience. About 20–45% women perceive their childbirth as a traumatic event, which may contribute to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)1. PTSD was characterized by the presence of trauma exposure with symptom presence for a month with at least one of the following symptoms: intrusion, avoidance, negative mood and cognitive changes as well as hyperarousal and reactivation2. Recently, PTSD following childbirth has gained growing attention. A systematic review of 59 studies originating from 23 countries with a total sample size of 24,267 women on all births including vaginal birth and cesarean section (CS) reported a mean prevalence of PTSD related to childbirth of 4.0% in community samples1. A number of studies3,4 have shown that PTSD has a negative impact on women, women’s relationship with their husbands and other family members, birth outcomes, as well as infant emotional and physical development.

Previous studies3,4,5 have demonstrated that various risk factors could contribute to the development of PTSD, including a history of psychologic issues, depression and anxiety, obstetric procedures, maternal and perinatal complications, negative experience with healthcare settings, perception of loss of control during birth, and lack of social support. In addition, some studies6,7,8,9,10,11 have reported that the mode of birth was associated with PTSD, however, of them, three studies6,7,8 found significant variance in symptoms of PTSD across the modes of birth they investigated, while other three studies9,10,11 did not find a significant association between mode of birth and PTSD.

While childbirth is a biological event, the pregnancy and birth experiences surrounding it are mostly social constructs, shaped by cultural perceptions and practices12. There are geographical and cultural variations in women’s attitudes towards childbirth and perception of mental health issues4,5,6. In our previous systematic review that about the prevalence of PTSD after CS, we did not identify any study specific to Chinese women13. Women in China have more traditional beliefs and practices about childbirth, such as preferring for boys, choosing a certain time to give birth, refraining from consuming “cold” food, which make them be more likely to have psychological problems, including maternal PTSD12. Besides, although the high CS rate in China has been declining recently after adopting the WHO recommendations, it continues to be higher than the recommended levels14. Given China’s large population base and relatively high CS rate, it is expected that there will be more CS mothers in the future. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to further clarify the relationship between CS and the occurrence of postpartum PTSD, so as to prevent and deal with the risk factors related to postpartum PTSD.

The present study aimed to conduct a prospective cohort study of Chinese women at childbirth in order to address the following research questions: (1) Whether CS is associated with the development of postnatal PTSD? (2) Is CS an independent risk factor for postpartum PTSD in Chinese women? (3) Explore measures to prevent and reduce the risk associated with postpartum PTSD.

Materials and methods

Study site

This study was conducted in The Seventh Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangdong, China, between October 2019 and Jun 2021. Approval from Human Research Ethics Committee of The Seventh Hospital of Southern Medical University was obtained before the commencement of the study. And this cohort study was conducted following The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement15. All women enrolled into this study participated on a voluntary basis and gave their written informed consents. Accuracy and precision of all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population

All women aged 20–45 years with a singleton pregnancy who visited The Seventh Hospital of Southern Medical University for prenatal care and planned to give birth at the same hospital were invited to participate in this study, and scored less than 13 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)16 at 3 days after childbirth. We excluded: (1) women with an existing or previous history of psychologic trauma or psychiatric disorder. (2) women with major physical comorbidity, including hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes, immune diseases or hematologic disease. (3) women with the following major obstetric and pregnancy complication: severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, placenta previa, placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, or major postpartum infection, or with serious neonatal problems such as major birth defects, premature infant, or birth weight < 1500 g.

Outcome measure

Mothers were assessed for PTSD at 42 days after childbirth using Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian version (PCL-C)17. PCL-C is a 17-item self-report rating-scale, including five items of re-experience, seven items of avoidance, and five items of hyperarousal. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale reflecting the severity of symptoms ranging from “not at all” (1) to “extremely” (5) within the last month. Total scores are calculated as the mean response across all items, ranging from 17 to 85, with a higher total score representing more severe PTSD symptoms. A threshold of 38 or higher was selected as the optimal cut-point for probable PTSD18. The Chinese version of PCL-C has shown great diagnostic agreement, sound reliability (Cronbach’s α above 0.77) and validity19. The PCL-C was administered at 42 days postpartum for two reasons: (1) Considering that the PCL-C assessed PTSD symptoms in the past month17. Research suggests that the rate of PTSD is likely to be highest between 4 and 6 weeks postpartum20. Administering the PCL-C at 42 days aligns with this timeframe, allowing us to capture the peak levels of PTSD symptoms that may arise following childbirth. (2) In China, the 42-day postpartum period corresponds with the routine maternal health check-up. This timing facilitates the integration of our study assessments into the existing healthcare schedule, making it more convenient for participants and ensuring a higher follow-up rate. Therefore, we decided to follow up the participants at 42 days postpartum.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between vaginal delivery (VD) women and CS women using descriptive statistics. The association between mode of birth and PTSD was analyzed using log binomial regression analysis to provide crude and adjusted estimations. The obstetrical factors included in the adjusted log binomial regression were parity, anxiety during pregnancy, depressed during pregnancy, and fear of birth. Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used as effect measures. Two-sided test was applied in all statistical analyses, with P < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant. SPSS version 26.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

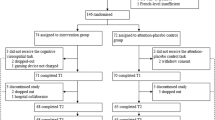

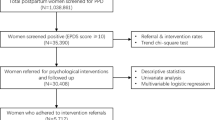

A total of 800 mothers met our eligibility criteria and were enrolled into this study at 3 days after childbirth. Of them, 18 mothers were excluded because of invalid questionnaires and 23 mothers were lost to follow-up, leaving 759 mothers were suit (94.90%) for the final analysis (Fig. 1). The details of the distribution of baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were 440 mothers (57.90%) gave birth vaginally and 319 mothers (42.10%) delivered by CS (including 237 elective and 82 emergency CS, Fig. 2). The majority (65.61%) of them were between the ages of 25 and 34 years, and 42.02% women were unemployed, 72.86% women graduated from secondary school, 88.93% women were married, 39.66% women were nulliparous.

The PCL‑C scores and rate of postpartum PTSD in study participants

The total symptom score, scores for reexperience, avoidance, and hyperarousal were all lower in VD women when compared to CS women (Table 2). According to our statistics, there were 12.12% (92/759) women finally developed postpartum PTSD within 42 days after childbirth. The prevalence of postpartum PTSD within 42 days after childbirth was 8.18% (36/440) in mothers with VD, much lower than 15.19% (36/237) in elective CS mothers and 24.39% (20/82) in emergency CS mothers (Fig. 3). More details are shown in Table 3.

Results of multiple log‑binomial regression analysis

Table 4 shows the results of analysis of the association of PTSD with potential confounding factors considered in this study in with VD women. Nulliparous (adjusted RR 2.74, 95% CI 1.31 to 5.76), anxiety during pregnancy (adjusted RR 2.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 4.53), depressed during pregnancy (adjusted RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.68) and fear of birth (adjusted RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.67) were independent risk factors for PTSD. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the risk of PTSD was increased for elective CS women (adjusted RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.87) and emergency CS women (adjusted RR 1.95, 95% CI 1.08 to 3.83) as compared with VD women (Table 5).

Discussion

Main findings

Our prospective cohort study of Chinese women revealed that CS may be an important independent risk factor of postpartum PTSD. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, we found that both elective CS and emergency CS were associated with an increased risk of developing postpartum PTSD compared to VD. Additionally, nulliparous status, anxiety during pregnancy, depression during pregnancy, and fear of birth were identified as independent risk factors for PTSD.

Interpretations

Previous studies21,22 have shown that a woman’s birth experience is closely related to the onset of postpartum PTSD. Yakupova et al.21 found that women who had a cesarean birth, or a greater number of medical interventions, or experienced obstetric violence during childbirth, had higher levels of postpartum PTSD symptoms. According to Ertan et al.22, women could suffer from mental health disorders related to birth experience during the postpartum. Unpleasant birth experiences and the occurrence of postnatal PTSD often determine a woman’s willingness to have children again. In other words, the occurrence of postnatal PTSD is directly related to human reproduction and healthy population growth, especially for countries with aging problems and some developed countries23, such as China, Japan, Russia and South Korea. World Population Prospects 202223 showed that the fertility rates of Korea, China, Japan and Russia are 0.88, 1.16, 1.30 and 1.49, respectively. Our study in a cohort of Chinese women with high CS rate revealed that the prevalence of PTSD in postpartum women was 12.12%. This number was higher than that reported in a meta-analysis in 2023, which combined 18 studies of postpartum PTSD and indicated the pooled prevalence of postpartum PTSD was 11.2% in Mainland China, with a higher prevalence at the time point within first month postpartum (18.1%)24. We conducted a systematic review of 9 studies originating from 7 countries with a total of 1,134 women and found that the pooled prevalence of PTSD after CS was 10.7%, and pooled prevalence of PTSD after emergency CS was higher than that after elective CS13. Variations in test used to detect PTSD, time points at measurement of PTSD, geographical origin of study, risk profile of PTSD, and methodological quality may explain the differences in the reported PTSD prevalence rates.

This study supported that CS was a significantly risk factor of PTSD. Findings of this study suggest that the prevalence of PTSD was 17.55% in women delivered by CS, which was about two-times higher than that in women who delivered vaginally. Specifically, the prevalence of postpartum PTSD within 42 days after childbirth was 24.39% (20/82) in emergency CS mothers. A systematic review1 with a total of 24,267 women reported a prevalence of PTSD related to childbirth of 4.0% in community samples, suggesting that CS may be an important traumatic event. Besides, a prospective cohort study with 1824 women also identified CS as a risk factor for PTSD symptoms7. CS women show more frequent a feeling of disappointment, poor body feeling, and lower self-confidence. And a worsening of mood and a decrease in self-esteem could be detected in women who give birth by CS6. In addition, CS women worried more about the safety of their baby and felt less satisfied overall with their birthing experiences, which may lead to women may perceive CS as more traumatic than VD.

An elective CS is defined as a planned CS without strict medical indication and performed before the start of labour25. Elective CS is usually performed when medical indications such as placenta previa and pre-eclampsia present, but elective CS also be a traumatic event as it brings physical trauma even psychological to women26. Findings of this study suggest that the prevalence of PTSD was 15.19% in women delivered by elective CS. Nagle et al.27 reported an increased risk following CS for severe maternal morbidities, complications in newborn medical health. Besides, a study conducted by Dekel et al.6 showed that complications in psychologically derived factors such as maternal bonding are related to CS. Increased risk of PTSD following CS may in part reflect these negative impacts of CS.

Emergency cesarean birth is considered to be the most traumatic mode of birth, because of the stress associated with needing emergency surgery, often when a woman is in established labor28. Except for the same negative results as elective CS, emergency CS women usually have an unpleasant birth experience9. The negative emotions, fear, and painful experiences associated with emergency CS can contribute to the formation and consolidation of fear memories, potentially leading to postpartum PTSD30. Childbirth pain, particularly from cervical dilation, has been shown to be highly distressing27,28 and can stimulate the amygdala region of the limbic system, a key area involved in the formation of conditioned fear memories—a core symptom of PTSD31. A study conducted by Du et al.32 found that analgesia pump use was a protective factor against postpartum PTSD. The release of norepinephrine during stressful and traumatic events can increase the formation of event-related fear memories, thus inducing PTSD33. Sedative and analgesic drugs delivered via an analgesic pump may prevent the onset and development of PTSD by lowering the important source of norepinephrine in the central nervous system and reducing the consolidation, reinforcement and formation of conditioned fear memories during the early stage of trauma34. Besides, a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Carter et al.28 found that women who developed PTSD after emergency CS felt less in control and less supported than those who did not develop it after the same procedure. Therefore, ensuring that women feel supported and in control during CS may mediate against this risk21,22.

Our study also indicated that negative emotions during pregnancy were risk factors for developing PTSD, including fear of birth, anxiety and depressed during pregnancy. Fear of birth increased the risk of a negative subjective birth experience which in turn may lead to PTSD. Avignon V et al.35 found that fear of birth may result in fatigue and sleep deprivation during pregnancy, which may be another explanation for why women with fear of birth were more likely to suffer from PTSD. A cohort study conducted by Steetskamp J et al.5 also showed that negative emotions, distress and a generally negative experience of labor were connected with the development of PTSD. Therefore, paying attention to the psychological status of pregnant women and providing appropriate psychological intervention may contribute to reducing the prevalence of PTSD21,22,27. In addition, our study found that nulliparous women are more likely to suffer PTSD. Among primiparous women, the relative risk of developing a PTSD symptom profile after CS was 6.3 times higher compared to normal vaginal deliveries6. Nulliparous women have more uncertainty about birth, which may increase their perceived birth pain. A cohort study conducted by Steetskamp et al.5 found that birth pain was considered a highly predisposing factor for developing PTSD.

The best way to prevent the onset the disease is by active prevention. Therefore, on the basis of this study and literature reviews21,22,27, we give the following preventive recommendations: (1) strict control the indications of CS to reduce the CS rate; (2) conduct health education related to childbirth for pregnant women to make them know and understand the perinatal process as much as possible to eliminate the fear and anxiety of the unknown; (3) health education for the family members of pregnant women to popularize perinatal knowledge so that the pregnant women can obtain enough family support; (4) family members and medical personnel should pay close attention to maternal psychological changes in the perinatal period, find and provide timely help and support, when necessary, preventive psychological intervention.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the association between mode of birth and PTSD among women in Guangdong province of China. We carefully assessed potential confounders and performed appropriate methods to adjust for the effect of these confounders. The consistent results from different models in the adjustment suggest the robustness of the association between mode of birth and PTSD. In addition, design and analysis of this study was based on a systematic review that we conducted before.

Of course, there were several limitations for consideration in interpreting the results. (1) Limitations in analysis: while our analysis includes most of the important antepartum and intrapartum risk factors reported in the literature, some potential postpartum risk factors such as postpartum care provider and postpartum living environment, have not been taken into consideration in the regression analysis. Second, (2) Limitations in data collection: PCL-C was used to classify PTSD. It should be noted that this is a screening measure not a diagnosis. We chose the PCL-C as a screening tool primarily due to its reliability and validity in assessing PTSD symptoms across a broad range of populations. Instruments specifically designed for birth trauma, such as the Birth Trauma Scale (BTS), as well as a diagnostic tool may provide a more comprehensive picture of PTSD. (3) Limitations in sample selection: the study was conducted in a single medical institution. Whether the results could be generated to other regions of China remains to be explored.

Conclusion

Our study conducted with a cohort of Chinese women unveiled that CS emerged as a significant risk factor for the development of PTSD. Facilitating an environment where women feel supported and empowered during CS may serve as a potential mediator against this risk. Pregnant women should receive comprehensive education regarding childbirth, encompassing the benefits of VD, the natural birthing process, and essential considerations. This approach can effectively enhance pregnant women’s confidence in opting for natural birth. Implementing various professional practices such as optimizing delivery positions and providing Doula-assisted deliveries could significantly improve women’s overall childbirth experience while simultaneously reducing stressors associated with labor, ultimately mitigating the likelihood of developing PTSD.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due Chinese data safety restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yildiz, P. D., Ayers, S. & Phillips, L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 208, 634–645 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (Arlington,2013).

Fameli, A. L., Costa, D. S. J., Coddington, R. & Hawes, D. J. Assessment of childbirth-related post traumatic stress disorder in Australian mothers: psychometric properties of the City Birth Trauma Scale. J. Affect. Disord. 324, 559–565 (2023).

Yonkers, K. A. et al. Pregnant women with posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of preterm birth. JAMA Psychiatry 71(8), 897–904 (2014).

Steetskamp, J. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: prevalence and associated factors a prospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306(5), 1531–1537 (2022).

Dekel, S. et al. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch. Womens Ment Health 22(6), 817–824 (2019).

Furuta, M., Sandall, J., Cooper, D. & Bick, D. Predictors of birth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms: secondary analysis of a cohort study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19(6), 987–999 (2016).

Feeley, N., Hayton, B., Gold, I. & Zelkowitz, P. A comparative prospective cohort study of women following childbirth: mothers of low birthweight infants at risk for elevated PTSD symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 101, 24–30 (2017).

Noyman-Veksler, G., Herishanu-Gilutz, S., Kofman, O., Holchberg, G. & Shahar, G. Post-natal psychopathology and bonding with the infant among first-time mothers undergoing a caesarian section and vaginal delivery: sense of coherence and social support as moderators. Psychol. Health 30(4), 441–455 (2015).

Polachek, I. S., Harari, L. H., Baum, M. & Strous, R. D. Postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: the uninvited birth companion. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 14(6), 347–353 (2012).

Cohen, M. M., Ansara, D., Schei, B., Stuckless, N. & Stewart, D. E. Posttraumatic stress disorder after pregnancy, labor, and delivery. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 13(3), 315–324 (2004).

Withers, M., Kharazmi, N. & Lim, E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: a review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 56, 158–170 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder following caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 29(2), 200–209 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Risk factors for failure of conversion from epidural labor analgesia to cesarean section anesthesia and general anesthesia incidence: an updated meta-analysis. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal. Med. 36 (2), 2278020 (2023).

Von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61(4), 344–349 (2008).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 150, 782–786 (1987).

National Center for PTSD. Using the PTSD checklist for DSM-IV (PCL). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_Psychometric_Information.pdf (2024).

Harrington, T. & Newman, E. The psychometric utility of two self-report measures of PTSD among women substance users. Addict. Behav. 32(12), 2788–2798 (2007).

Li, H. et al. Diagnostic utility of the PTSD checklist in detecting ptsd in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychol. Rep. 107(3), 733–739 (2010).

Dikmen-Yildiz, P., Ayers, S. & Phillips, L. Depression, anxiety, PTSD and comorbidity in perinatal women in Turkey: a longitudinal population-based study. Midwifery 55, 29–37 (2017).

Yakupova, V. & Suarez, A. Postpartum PTSD and birth experience in russian-speaking women. Midwifery 112, 103385 (2022).

Ertan, D., Hingray, C., Burlacu, E., Sterlé, A. & El-Hage, W. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry 21(1), 155 (2021).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World PopulationProspects 2022:SummaryofResuls.UN DESA/POP/2022/TRNO.3 (2022).

Meili, X. et al. Prevalence of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder and its determinants in Mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Psychiatr Nurs. 44, 76–85 (2023).

FA. Timing of elective pre-labour caesarean section: a decision analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 59(2), 221–227 (2019).

Mylonas, I. & Friese, K. Indications for and risks of Elective Cesarean Section. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 112(29–30), 489–495 (2015).

Nagle, U. et al. A survey of perceived traumatic birth experiences in an Irish maternity sample—prevalence, risk factors and follow up. Midwifery 113,103419 (2022).

Carter, J., Bick, D., Gallacher, D. & Chang, Y. S. Mode of birth and development of maternal postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Birth 49(4), 616–627 (2022).

Karlström, A. Women’s self-reported experience of unplanned caesarean section: results of a Swedish study. Midwifery 50, 253–258 (2017).

Hüner, B. et al. Post-traumatic stress syndromes following childbirth influenced by birth mode-is an emergency cesarean section worst? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 309(6), 2439–2446 (2024).

Chaaya, N., Battle, A. R. & Johnson, L. R. An update on contextual fear memory mechanisms: transition between Amygdala and Hippocampus. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 92, 43–54 (2018).

Du, F. et al. Risk factors for postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder after emergency admission. World J. Emerg. Med. 15(2), 121–125 (2024).

Soeter, M. & Kindt, M. Noradrenergic enhancement of associative fear memory in humans. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 96(2), 263–271 (2011).

Wang, Y. X., Mao, X. F., Li, T. F., Gong, N. & Zhang, M. Z. Dezocine exhibits antihypersensitivity activities in neuropathy through spinal µ-opioid receptor activation and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Sci. Rep. 7, 43137 (2017).

Avignon, V., Baud, D., Gaucher, L., Dupont, C. & Horsch, A. Childbirth experience, risk of PTSD and obstetric and neonatal outcomes according to antenatal classes attendance. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 10717 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to all participants in The Seventh Hospital of Southern Medical University for their contributions to this study.

Funding

Guangzhou Health Science and Technology Program(20251A011083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BX, YC conceptualized and designed the study. JT made major contributions to the acquisition of the data. BX drafted the paper; YC critically reviewed and revised the paper, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Each author certified that they had participated sufficiently in the work to believe in its overall validity and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of its content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval from Human Research Ethics Committee of The Seventh Hospital of Southern Medical University was obtained.

Ethical statement

There was no harm to the participants. All women included in our study knew our research objective and procedure. All women enrolled into this study participated on a voluntary basis and gave their written informed consents.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, B., Chen, Y. & Tang, J. A prospective cohort study of the association between mode of delivery and postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder. Sci Rep 15, 4149 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88717-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88717-7