Abstract

Metal toxicity in groundwater surrounding coal mines is a major concern because it may pose a significant risk to human health of the local populace. The present study investigated Al, As, Ba, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, Se, Sr, and Zn concentrations in the groundwater of Umaria coalfields during the post-monsoon season and pre-monsoon season. The study was carried out to investigate the spatial and temporal variation of the metals in the groundwater along with statistical source identification of the metals and assessment of human health risks due to intake of the metals through the groundwater. The metals of concern were Al, Fe and Mn, which exceeded the Indian drinking water quality standards in 26%, 38% and 12% of samples in the post-monsoon season and 38%, 40% and 14% of samples in the pre-monsoon season. A marked decrease in metal concentrations in the post-monsoon season was also observed, which may be attributed to the dilution effect associated with the heavy rainfall during the monsoon season. Principal component analysis used to identify contamination sources of the metals indicated geogenic attributes, coal mining activities and vehicular load as the sources of the metals in the groundwater. The human health risk assessment suggested considerable risk to the local populace using the groundwater for drinking purposes. The probable health risk, as suggested by the Hazard Index, depicted a higher risk to the child population as opposed to the adults. The Hazard Index for the child population was greater than unity in 60% and 76% of the samples in the post- and pre-monsoon seasons, respectively, suggesting a significant risk of metal exposure from groundwater intake. The study also suggested that ingestion was the primary exposure pathway and risk due to dermal exposure was trivial. The carcinogenic risk due to As and Cr were within the acceptable limits except for one location each for As and Cr. The present study suggests a potential non-carcinogenic human health risk due to groundwater intake; hence, the study area needs routine groundwater quality monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal mining is a major industry that generates 41% of the world’s electricity1,2. However, there are a lot of environmental consequences of coal mining worldwide, particularly its effects on the water resources3,4. In India also, coal mining leads to water quality issues in surface and groundwater resources, instigating the residents of the coal mining areas to struggle with potable water availability5,6,7. During the mining processes, such as coal extraction and processing, heavy metals can be released into the environment. There is a significant threat to human and environmental health from these contaminants since they can seep into groundwater systems8,9.

Groundwater is a valuable resource in many coal mining areas, providing drinking water, irrigation, and industrial applications10. Mining-induced heavy metal migration into groundwater is a multifaceted environmental issue. The prolonged presence of contaminants in the environment might lead to their accumulation in groundwater, therefore possibly impacting significantly large populations. In order to safeguard public health and maintain the long-term viability of water resources, it is imperative to evaluate the hazards linked to groundwater metal contamination11. Groundwater quality in mining sites can be damaged due to metal leaching, including arsenic (As), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), and cadmium (Cd)12. Elevated levels of these metals in groundwater can lead to detrimental impacts on human health, such as neurological diseases, renal impairment, and malignancy13. Skin lesions, developmental consequences, and cancer have been associated with arsenic exposure14. Lead can affect children’s cognition and adult cardiovascular health15.

Groundwater is intensively used for drinking and irrigational uses, and thus, its quality has been a major concern worldwide16,17. Recent studies have demonstrated the dissemination of metals contaminating groundwater in coalfield regions both nationally and globally, presenting a significant concern. Investigations in the Wardha Valley Coalfields of India uncovered elevated concentrations of heavy metals, including iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb), frequently surpassing the allowed limits for safe drinking water18. Research in the Jharia Coalfield revealed seasonal fluctuations in metal concentrations, highlighting the necessity for ongoing monitoring and mitigation strategies19.

Mining activities in China contaminated groundwater in the some coal mining areas with heavy metals such as As, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb, and Zn20,21,22. Groundwater contamination has also been detected around coal combustion product disposal facilities in the United States23. Heavy metal contamination in coal mining groundwater has been revealed in South Africa. This contamination poses a risk to local people who use groundwater for domestic uses24. Acid mine drainage (AMD) occurs when sulphide minerals are exposed during the mining process, releasing metals such as iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), arsenic (As), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg) into aquifers. Metal concentrations in coal-rich areas exceed permissible limits for drinking water25,26.

Effective management and remediation of the groundwater require a thorough understanding of contamination patterns and health effects. Health risks associated with metal contamination require robust risk assessment methods to quantify potential impacts and guide public health interventions27. Human health risk assessment also helps in classifying the metals responsible for the anticipated health hazards. The seasons, locations, and population groups with greater risks can be identified correspondingly. Advanced geographic information system (GIS) technology analyses and visualises geographical data on environmental contaminants and health hazards. The subsequent use of GIS after health risk assessment can build precise maps and models that show contamination patterns and high-risk locations using mining, and metal contamination data28. GIS helps researchers understand the distribution of contaminants and develop targeted interventions and policies7.

Extensive data gaps exist when evaluating metal contamination in groundwater resources in mining areas. Insufficient geographical and temporal coverage of metal contamination data, insufficient knowledge of metal transport routes, and absence of information on the long-term health consequences of exposure are among the gaps identified5. Addressing these gaps is critical for enhancing risk assessment and creating focused remedial measures for coal mining areas. The current study was carried out at Umaria coalfield in Umaria district, Madhya Pradesh, India, during November 2022 (post-monsoon) and June 2023 (pre-monsoon). The coalfield region is surrounded by many anthropogenic activities, including mining of coal and related activities, residential developments, and agricultural practices. However, to the best of our knowledge, no extensive studies have been carried out related to metal contamination in groundwater and the associated human health risk assessment in this coal mining area. Furthermore, in the Umaria coalfield, groundwater is a primary source for utilisation of drinking and domestic uses. Hence, a study related to groundwater contamination pertaining to metals is obligatory. Also, the knowledge regarding the effects of coal mining on groundwater quality, the probable sources of metal contamination and the likely risk to the health of the local population using the groundwater for drinking and domestic purposes is warranted. Keeping this in view, the study attempts (i) to evaluate metal contamination in groundwater in the coal mining area, (ii) to identify correlations and probable sources of heavy metal contamination in the mining area, (iii) to evaluate the probable human health risk due to the use of contaminated groundwater for drinking, (iv) GIS-based mapping of contamination levels and the calculated health risks. Thus, the study may provide information on the status of groundwater quality to provide practical insights to legislators, environmental agencies, and public health experts by integrating GIS and risk assessment approaches. The study holds the inevitability of protecting the groundwater resources, public health, and sustainable mining in the study area.

Materials and methods

Study area

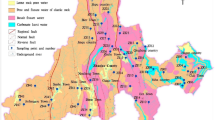

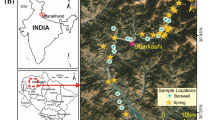

The Umaria coalfield (study area) is situated in the Umaria district, Madhya Pradesh, India (Fig. 1). The district has abundant mineral resources, with coal being a significant one. Umaria Coalfield’s land use maps (Supplementary Fig. 1) show that agriculture, forests, human settlements, barren land, and water bodies mainly cover the study area. A thermal power plant is also situated close to the study area. The climate of the district is classified into four seasons, i.e. summer season (March to mid-June), monsoon season (mid-June to September), transitional period (October and November) and winter season (December to February), respectively29. The district experiences an average annual precipitation of approximately 1248.8 mm29.

The map of the Umaria district29, study area and groundwater sampling locations in the Umaria coalfield.

Geologically, the study area is mostly dominated by the Gondwana Sedimentary Formation rocks underlain by Archean Metamorphics30. The stratigraphic classification of the litho-units is Archean Metamorphics at the lowermost layer, succeeded by a series of overlained formations known as Talchir, Barakar, and Supra Brakar30. The upper Barakar Formation has granular sandstone, shale, red clay, and coal seams. The Talchir Formation has marine sandstone containing fossils, clay, and shales. The major parts of the region are covered by the Gondwana Sedimentary Formation, which possesses promising aquifers29. The upper sedimentary formations exhibit both primary and secondary porosity. Groundwater in the district is primarily recharged by rain29. Groundwater level monitoring of the study area shows that the water level ranges from 1.9 m below ground level (mbgl) to 11.8 mbgl in the pre-monsoon season (pre-ms) and from 1.3 mbgl to 9.7 mbgl during the post-monsoon season (post-ms) with a groundwater fluctuation from 0.1 mbgl to 6.3 mbgl. The district has a population of 644,758, of which females and males were 314,084 and 330,674, respectively, as per the Indian census 2011. Out of the total population, about 83% of the population resides in rural areas of the district. The area’s residents primarily depend on the district’s available groundwater resources for drinking and domestic uses.

Sampling and analysis

To analyse the metals concentration in the groundwater of the Umaria coalfield, a systematic sampling was conducted in the post-monsoon season (post-ms) (November 2022) and the pre-monsoon season (pre-ms) (June 2023), respectively. A total of one hundred (100) groundwater samples were collected during the post-ms (n = 50) and pre-ms (n = 50) from various locations, including Amha, Amlai, Bhundi, Dagdauwa, Dhanwahi, Dhanwar, Karnpura, Kiratntal, Pipria, Mahura, Majhgawan, Munda Karkeli, Pinaura, Nowrozabad, Pali, Pondi, Sastra and Umaria (Fig. 1). A limited number of samples could be obtained from the western part of the study area because of its predominantly forest environment (Supplementary Fig. 1). Groundwater samples were collected in pre-washed polyethylene bottles (capacity 120 ml) after pumping the hand pumps/tube wells for some time, filtered with a 0.45 μm Millipore filter and preserved with supra-pure nitric acid31. Fourteen metals (namely Al, As, Ba, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, Se, Sr and Zn) concentration in the samples were determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS), model ELAN DRCe, Perkin Elmer.

Quality control

Instrument calibration standards and reagent blanks were examined with the samples to ensure the ICP-MS readings were accurate and precise. The results indicated that the concentrations of the standards fell within the ± 5% precision range. Along with the samples, a certified reference material (CRM) {NIST-1640a32 (natural water)} from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA (Table 1) was also tested in the same way. Then, the metal concentrations were compared to the certified concentration values. The analysis of the CRM resulted in appreciable recoveries from 95.8% to 104.9% of the certified values of the metals. Throughout the analysis, standard glassware and Millipore distilled water were used.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

One important statistical method for finding the probable sources of elements is PCA. It replaces the actual dependent variable (concentration of metals in the study) with a smaller number of theoretical independent variables called principal components (PC)33. The current study used the PCA method to identify the theoretical origins of analysed metals. The exploratory factor analysis was conducted using varimax rotation34, reducing the number of variables with a strong loading on each component and simplifying the interpretation of the principal component analysis outcomes35. The components with eigenvalues surpassing unity are exclusively considered to identify the likely origins36. The principal components score for each variable reflects the degree of correlation between the original variable and the component. A positive score above 0.5 indicates a good correlation between the specified variable and the PC.

Non-carcinogenic risk assessment on human health

Hazard quotients (HQs) were computed for all analysed metals under consideration to assess the non-carcinogenic risk associated with groundwater consumption pertaining to ingestion and dermal pathways. Hazard quotients for metals were determined by dividing the Average Daily Dose (ADD) calculated for the ingestion pathway (ADDing) and dermal pathway (ADDderm) by the corresponding Reference Dose (RfD). Table 2presents the formulae and input parameter values for calculating the non-carcinogenic risk in various population groups (adult male, adult female and child) for both ingestion and dermal pathways. RfD of a specific metal is the highest possible daily dose per unit of body weight, which is unlikely to negatively impact human health, considering the specific exposure routes. Hence, if the HQ is less than one, it can be considered safe pertaining to non-cancer hazards37.

The HQ quantifies the non-carcinogenic risk of one specific metal. However, considering the presence of many metals in the medium, such as drinking water, the overall risk is assessed by calculating the Hazard Index (HI), which combines the HQ values of all the metals under consideration. HI values more than 1 indicate potential adverse impacts on human health, thereby necessitating further investigation of the region38. The estimation of the HI, derived from dose additivity, is limited to screening applications due to its suppositional nature and lack of consideration for the process by which metals impact target organs or the human body39.

Assessment of carcinogenic risks

The carcinogenic risks were evaluated using Eq. (1), adhering to the methods established by42. The derived value represents the added probability of a person developing any form of cancer throughout their lifetime due to exposure to carcinogens. As per USEPA guidelines, the acceptable or tolerable range for carcinogenic risks falls within 10−6 to 10−4.

In this equation, ADD represents the daily intake averaged over 68.3 years (mg/kg/day), whereas SFo represents the oral slope factor, which is expressed as (mg/kg/day)−1. These slope parameters were taken from the USEPA’s risk-based concentration table, while the average life span of the Indian population was obtained from the World Health Organisation43.

Geographical information system (GIS)

GIS is widely used by researchers for graphical representation due to its reliability in collecting and organising data pertaining to environmental concerns and precisely establishing their spatial associations44. GIS-based outcomes can assist policymakers in making prompt strategic decisions to address environmental issues at local, national, and global scales45,46,47,48. Inverse distance weighting (IDW) is one of the important interpolation tools in the GIS environment for spatial distribution mapping of groundwater changes49. Hence, IDW interpolation has been used in a GIS environment to produce distribution maps of specific elements and computed risks to human health.

Results and discussion

Metal distribution

A total of 14 metals were analysed in the groundwater samples of the Umaria coalfield during post- and pre-monsoon seasons, and their statistical summary is presented in Table 3. As is common in environmental quality data, the metal concentration in the present study varies according to a log-normal distribution. Consequently, the geometric mean represents the central tendency (Table 3). The concentrations of Al vary from 1.83 µg/L to 101.7 µg/L, with a geomean value of 24.9 µg/L in the post-ms and from 4.65 µg/L to 99.7 µg/L, with a geomean value of 28.8 µg/L during the pre-ms. About 26% and 38% of the groundwater samples exceeded the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS, 2012)50 drinking water acceptable limit (30 µg/L) of Al during the post- and pre-monsoon seasons, respectively, in the coalfield (Fig. 2). The groundwater location GW14 has the highest concentration of Al during both seasons (Fig. 2).

The Fe concentrations range from 31.2 µg/L to 1176 µg/L (geomean 403 µg/L) in the post-ms and from 5.82 µg/L to 3119 µg/L (geomean 481 µg/L) in the pre-ms in the groundwater of the study area (Table 3). The concentration of Fe exceeded the BIS (2012)50 acceptable limit drinking water limit of 300 µg/L in 38% and 40% of the samples during the post- and pre-monsoon seasons, respectively (Fig. 3). The sampling location GW16 has the highest concentration of Fe in the post-ms while GW25 has the highest Fe concentration during the pre-ms (Fig. 3). The sampling locations 16, 17, 25, 26 and 37 have a value of Fe greater than 1000 µg/L in the post-ms, while 06, 16, 17, 24, 25, 37 and 38 in the pre-ms have Fe concentration higher than 1000 µg/L (Fig. 3). These locations were predominantly within close vicinity to the coal mines.

The concentrations of Mn vary from 2.14 µg/L to 312 µg/L, with a geomean value of 42.8 µg/L in the post-ms and from 1.26 µg/L to 358 µg/L, with a geomean value of 52.9 µg/L in the pre-ms in the coalfield (Table 3). About 12% and 14% of the samples exceeded the Mn acceptable limit of 100 µg/L established by the BIS (2012) during the post- and pre-ms seasons, respectively (Fig. 4). The groundwater location 29 has the highest concentration of Mn during both seasons (Fig. 4).

Nevertheless, the concentration of Ba, Pb, Cd, and Zn also exceeded the acceptable BIS (2012)50 water quality limits in a few groundwater samples (Table 3). However, As, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Se values in the coalfield groundwater samples were within the BIS drinking water guidelines for both seasons (Table 3). The findings suggest that the elevated Al, Fe, and Mn levels in groundwater render it unfit for drinking purposes in many locations (Table 3). These three elements primarily concern people in the study area, followed by Ba, Pb, Cd and Zn (Table 3).

Dissolved total metal load

The dissolved total metal load (sum of concentrations of all analysed metals) in the groundwater samples was higher in the pre-ms than in the post-ms, indicating dilution due to intense rainfall during the monsoon season. Figure 5shows that the metal load in the groundwater of the study area had an average of 1505 µg/L in the post-ms and about 2024 µg/L in the pre-ms. The Umaria district receives its maximum rainfall during the southwest monsoon season, which takes place from June to September, and it is the primary source of groundwater replenishment in the area29. Previous investigations have reported similar findings, indicating that the metal load is reduced during the monsoon and post-monsoon seasons compared to the pre-monsoon season due to dilution caused by rainfall47,51,52,53.

Comparison with other studies

Table 4 compares the metal concentration in the groundwater of the Umaria coalfield with selected national and international coalfield groundwater studies. Table 4 shows that the groundwater of the Umaria coalfield is comparable with most of the other coalfield groundwater. However, Iron concentration in the groundwater is considerably lower than the groundwater from some Indian coalfields (East Bokaro, West Bokaro, North Karanpura, Korba, Tachir and Neyveli) and a coalified of Bangladesh (Barapukuria). The concentration of Al, As, Ba and Cd were also lower as compared to the groundwater from few other coalfields (Korba and Talchir from India; Tshikondeni coalfield of South Africa). The Cr and Cu content in the groundwater of the Umaria coalfield is comparable to other studies except for Neyvelli, Talchir and Tshikondeni coalfields, which depicted higher contents of the metals. The Mn concentration is comparable with the West Bokaro coalfield of India and the Hauinan and Sulin coalfields of China. However, the Mn value is much lower than the Ib Valley, Korba, East Bokaro, North Karanapura and Talcher coalfields of India and the Tshikondeni coalfield of South Africa. The Mn value in the Umaria coalfield groundwater is higher than that of other coalfields’ groundwater, such as Brajrajnagar of India and Barapukuria coalfield of Bangladesh. The variation in the concentration of the metals in the groundwater of the different coalfields may be attributed to their geological attributes and anthropogenic inputs.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA is a method used to reduce complexity in multivariate data and identify the relationships between variables. A PCA analysis was conducted by using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test in statistical software (i.e. IBM SPSS 21). The KMO conduct is a sampling acceptability technique that quantifies the percentage of variance resulting from the main principal components. Table 5 presents the PCA loadings of fourteen metals for post-ms and pre-ms seasons, together with their eigenvalues, variance explained by each component and the cumulative variance explained. The findings indicate the presence of three main components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) involving prominent groups of heavy metals and cumulatively accounting for 62.39% of the variance in the data.

Principal Component 1 (PC1) accounted for 24.3% of the total variance and has significant loadings of Mn (0.74), Cu (0.70), Ni (0.68), As (0.83), Se (0.68), and Ba (0.82). Potential sources of these metals in groundwater include coal mining operations, coal beneficiation and processing units. The effluents introduce various metals and ions into the underground water, which can impact its quality by leaching65,66. The leaching of Cu, As, Cd, Co, and Pb into groundwater is also attributed to the combustion of coal in power-generating facilities. Previous investigations have demonstrated that leachate originating from coal mines and thermal power plants is a major factor in water contamination67,68,69. Principal component 2 (PC2) accounted for 22.4% of the variance and includes high loadings of Co (0.83), Cd (0.66), Al (0.64), Sr (0.85), and Fe (0.87). This component appears to be related to natural sources.

Principal Component 3 (PC3) accounted for 15.7% of the total variation reported, with the highest loadings observed on Pb (0.85), Zn (0.86), and Cr (0.65). This component is an indicator of contamination mostly that originates from vehicular sources. Lead (Pb) is a well-established contaminant often linked to engine emissions (historically from leaded petrol)70. Although attempts have been made to decrease the presence of lead in the environment, it continues to be a major environmental issue because of its inherent persistence and toxicity, especially in urban and industrial areas71. Pb is also a constituent of fuel tanks, batteries, bearings, etc., used in automobiles72. Vehicle tyres also contain Pb and Zn, and thus, wearing down of the tyres can be a probable source of Pb and Zn73,74. Zn is also used as a minor additive in fuel and lubricants75. The use of Cr in the catalytic converters and brake linings epitomizes the vehicular sources of the metal76.

Human health risk assessment

Non-carcinogenic risk

A comprehensive evaluation of non-carcinogenic human health hazards was carried out for male, female, and child populace considering the ingestion and dermal pathways. Tables 6 and 7depict the calculated Hazard Quotients (HQ) of analysed metals using the geometric mean associated with the ingestion of groundwater from the Umaria coalfield for post-ms and pre-ms, respectively. For the post-ms, the highest HQ was depicted for Co, followed by As and Mn. In the same pattern, during the pre-ms also, the highest HQ values were evaluated for Co (0.13, 0.11 and 0.20 for males, females and child, respectively), followed by As and Mn. Furthermore, among all the population groups, the highest HQ value was computed for Co (0.20), followed by As (0.17), Mn (0.13), and Ba (0.10) for the child population during the pre-ms. The HQs of all elements, calculated using geometric mean concentrations, were below 1 for all the population groups for both seasons, indicating that these metals individually represented little hazards for the residents consuming the groundwater. The probable non-cancer risks due to the cumulative effect of the considered metals via the ingestion pathway are evaluated using the Hazard Index (HI). The Hazard Index (HI) was determined by summing all the HQs. The HI for both males and females remained below 1 in both seasons, indicating that the risk of non-carcinogenic health impacts is within acceptable limits, suggesting lower exposure or greater physiological capacity to handle contaminant loads without adverse effects77. A further reduction in HQ was observed in the post-ms, which could be attributed to a decrease in contaminant concentration following rainfall, thus lowering the risk for adult populations. The HI for child was found to be greater than one (1.01) for the child populace (Table 7) during the pre-ms, indicating a significant risk of metal exposure from groundwater intake78. Children are more vulnerable to toxic exposures due to their smaller body size, higher consumption rates relative to body weight, and ongoing development of their biological systems79.

During the pre-ms, considering all the locations, the HI values for male, female, and child populations were recorded > 1 in 38%, 30%, and 76% of the groundwater samples, respectively (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). In the post-ms, the HI values were greater than 1 in 32%, 28%, and 64% of the groundwater samples for male, female and child populations, respectively (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). Since the HI is greater than unity in quite a few locations, it can be inferred that there is a probable risk to the consumers of the groundwater, considering the cumulative effects of the metals. The elevated HI in children (Fig. 8) suggests that they are particularly vulnerable to exposure to metal contaminants, even when concentrations are reduced in the post-ms season. The higher HI values are likely due to physiological factors, such as faster metabolism and different absorption rates, making child more susceptible to the effects of contaminants compared to male and female80. Considering the locations, higher HI was depicted in the sites which were in close vicinity of coal mining areas (locations 16, 17, 29, 37, 50).

The HQderm(hazard quotient by dermal absorption) of all the metals for all the population groups were evaluated to assess the risk to human health through dermal exposure of the metals in the groundwater. The HQderm of all the metals across all 50 locations for the post-ms season and pre-ms season are depicted in Fig. 9a and b, respectively. The HQderm for the adult and child populations were far below unity, indicating that these metals posed little hazards via dermal absorption. The largest value of HQderm, considering the geometric mean, was 0.01, which was for Mn for child populace in the pre-monsoon season. Considering all the locations, the HQderm of Mn ranged from 0.0009 to 0.066 in the post-ms (Fig. 9a) while it varied from 0.0005 to 0.082 in the pre-ms (Fig. 9b). The Hazard Index (HI) due to the dermal exposure route was also estimated by adding the HQs, however, the HI due to dermal exposure did not surpass unity for any of the population group in any of the locations for both the seasons. Nevertheless, considering the population groups, the highest risk was for the child population. The HI due to dermal exposure varied from 0.02 to 0.19 and 0.01 to 0.23 for the child populace during the pre-ms and post-ms seasons, respectively. Thus, it can be inferred that the ingestion pathway is the primary exposure pathway for the metals in the groundwater in the study area, and dermal absorption had no or little health threat.

Carcinogenic human health risk

Out of the metals analysed in groundwater, As and Cr has been categorized as a recognized human carcinogen by both the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the Integrated Risk Information System of the USEPA38,81. Thus, the evaluation of carcinogenic risk in this study was carried out on the levels of As and Cr found in groundwater. However, it may be noted that Cr(VI) has been related to carcinogenic risk, and since speciation of Cr could not be done in the present study, total Cr analysed was taken up for the carcinogenic assessment. This carcinogenic risk evaluation of Cr has been done with an assumption that all the Cr in the groundwater was in the form of Cr(VI). This might be an overestimation of the cancer risk of Cr.

When considering the geometric mean for the entire study area, the calculated carcinogenic risk in the post-ms season, the cancer risk for As and Cr was calculated 1.58 × 10−5 and 2.34 × 10−5 for male, 1.36 × 10−5 and 2.01 × 10−5for female, and 6.32 × 10−6 and 9.35 × 10−6 for children, respectively (Table 6). However, for the pre-ms season associated with oral intake of As and Cr was 1.65 × 10−5 and 2.40 × 10−5 for male, 1.42 × 10−5and 2.07 × 10−5for female, and 6.59 × 10−6 and 9.59 × 10−6 for children, respectively (Table 7). Since the cancer risk remains below the specified target risk of 1 × 10 − 4, it can be estimated as an “acceptable” value as provided by the USEPA. While accounting for the different locations, the probable cancer risk of As exceeded the permissible limits of 1 × 10−4 in one location (GW37) for the male and female populace in both seasons, while for Cr, the risk surpassed the limits in one location (GW12) in both the seasons for all the population groups.

Conclusions

The present research focused on the evaluation of metals and identification of their sources in groundwater of the Umaria coalfield in Madhya Pradesh. The study also used systematic health risk indices to assess potential health risks due to metal contamination to local population. The levels of Al, Fe, Mn, Ba, Pb, Cd and Zn exceeded Indian drinking water quality guidelines BIS (2012) in some of the locations. The concentrations of the metals were generally higher in the pre-monsoon season as compared to the post-monsoon season. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results show that the data is divided into three principal components collectively accounting for 62.4% of the variance, with initial eigenvalues greater than one. Furthermore, the PCA indicated that metals were present in the groundwater of the study area due to both natural and human activities. This analysis revealed that elevated amounts of metals were identified in close vicinity to industrial and coal mining sites, implying that human activities had a substantial impact on their concentrations. The study emphasises the importance of focused risk management techniques for child, especially during the pre-ms period when metal contaminants are more concentrated. The study depicts that the male and female populations have lower risks while the child population remain vulnerable, emphasising the necessity for ongoing environmental monitoring and intervention methods to protect public health. The study also depicts that the ingestion pathway is the primary exposure pathway for the metals in the groundwater in the study area, and dermal absorption had no or little health threat. The carcinogenic risk due to As and Cr were within the acceptable limits except for one location each for As and Cr. The findings hold immense importance for public health management, as they can guide policymakers in implementing remediation strategies, ensuring safe drinking water, and protecting vulnerable populations from chronic health conditions caused by metal exposure. Additionally, the study contributes to broader environmental research by providing a model for assessing human-induced contamination in coalfield regions, thus offering scope for comparative studies in other mining areas worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

McHugh, L. World energy needs: A role for coal in the energy mix. Issues in Environmental Science and Technology No. 45 Coal in the 21st Century: Energy Needs, Chemicals and Environmental Controls, Edited by R.E. Hester and R.M. Harrison, Published by the Royal Society of Chemistry (2017).

World Coal Association, Coal and & Infrastructure, M. World Coal Association, London, (2013).

Alhamed, M. & Wohnlich, S. Environmental impact of the abandoned coal mines on the surface water and the groundwater quality in the south of Bochum, Germany. Environ. Earth Sci. 72, 3251–3267 (2014).

Sun, K. et al. Impact of coal mining on groundwater of Luohe Formation in Binchang mining area. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 8 (1), 88–102 (2021).

Singh, A. K., Mahato, M. & Neogi, B. Quality assessment of mine water in the Raniganj Coalfield area, India. Mine Water Environ. 29, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-010-0108-222 (2010).

Singh, A. K., Mahato, M. K. & Neogi, B. Environmental geochemistry and quality assessment of mine water of Jharia Coalfield, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 65, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1064-2 (2012).

Mazinder, Baruah, P. & Singh, G. Assessing the utilization potential of pumped-out mine water for potability in the water-stressed coal mining region of Jharia, India: a quantitative, qualitative and probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ. Develop Sustain. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-02973-z (2023).

Jordaan, A. et al. Environmental impacts of coal mining and coal utilization. Environ. Sci. Policy. 13 (7), 749–756 (2010).

Zhang, S. et al. Impact of coal mining on groundwater quality and health risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (12), 7896–7905 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Assessment of groundwater quality in coal mining areas. Water Qual. Res. J. 54 (4), 405–418 (2019).

Miller, C. L. et al. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in environmental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 15 (6), 1200 (2018).

Sahoo, S. K. et al. Groundwater contamination in coal mining regions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 186 (3), 1557–1570 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Heavy metal contamination and human health risks in mining areas. Sci. Total Environ. 678, 124–135 (2019).

Smith, A. H. et al. Arsenic epidemiology and drinking water standards. Science 314 (5801), 637–640 (2006).

Gordon, C. W. et al. Lead exposure and health effects. Environ. Health Perspect. 127 (8), 085001 (2019).

Ali, S. et al. Groundwater quality assessment using water quality index and principal component analysis in the Achnera block, Agra district, Uttar Pradesh, Northern India. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56056-8 (2024).

Ghosh, A. & Bera, B. Hydrogeochemical assessment of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation applying groundwater quality index (GWQI) and irrigation water quality index (IWQI). Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 22, 100958. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2023.100958

Ganvir, P.S. & Guhey, R. An Implication of Enhanced Rock Weathering on the Groundwater Quality: A Case Study from Wardha Valley Coalfields, Central India. Weathering and Erosion Processes in the Natural Environment, 21, 215-242 (2023)

Panigrahy, B.P. et al. Assessment of heavy metal pollution index for groundwater around Jharia coalfield region, India. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 6 (3), 33-39 (2015)

Qiu, H., Gui, H., & Song, Q. Human health risk assessment of trace elements in shallow groundwater of the Linhuan coal-mining district, Northern Anhui Province, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 24(5), 1342-1351 (2018)

Wang, L. et al. Environmental and health risks posed by heavy metal contamination of groundwater in the Sunan Coal Mine, China. Toxics, 10(7), 390 (2022)

Chen, J. Gui, H. Guo, Y. & Li, J. Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Shallow Groundwater of Coal–Poultry Farming Districts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19(19), 12000 (2022)

Carlson, C.L. & Adriano, D.C. Environmental impacts of coal combustion residues. J. Environ. Qual. 22(2), 227-247 (1993)

Nephalama, A. Muzerengi, C. Assessment of the influence of coal mining on groundwater quality: Case of Masisi Village in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Proceedings of the Freiberg/Germany, Mining Meets Water—Conflicts Solutions, Leipzig, Germany, 11-15, (2016)

Acharya, B.S. & Kharel, G. Acid mine drainage from coal mining in the United States–An overview. J. Hydrol. 588, 125061 (2020)

Galhardi, J. A. & Bonotto, D. M. Hydrogeochemical features of surface water and groundwater contaminated with acid mine drainage (AMD) in coal mining areas: a case study in southern Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res, 23, 18911-18927 (2016)

Wei, X et al. Occurrence, mobility, and potential risk of uranium in an abandoned stone coal mine of Jiangxi Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 83(18), 531 (2024)

Suh, J., Kim, S. M. Yi, H. & Choi, Y. An overview of GIS-based modeling and assessment of mining-induced hazards: Soil, water, and forest. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 14(12), 1463 (2017).

CGWB (Central Ground Water Board). District Ground Water Information Booklet, Umaria District, Madhya Pradesh, Published by Ministry of Water Resources, Central Ground Water Board (North Central Region, Government of India, 2013).

Srivastava, S. C. Anand-Prakash. Palynological succession of the lower Gondwana sediments in Umaria Coalfield, Madhya Pradesh, India. The Palaeobotanist 32 (1), 26–34 (1984).

Radojevic, M. & Bashkin, V. N. Practical Environmental Analysis (Royal Society of Chemistry, 1999).

NIST. Certificate of analysis for standard reference material 1640a, trace elements in natural water. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA (2010).

Giri, S., Tiwari, A. K., Mahato, M. K. & Singh, A. K. Spatio-temporal variations of metals in groundwater from an iron mining impacted area: assessing sources and human health risk. Total Enviro Res. Themes, 8, 100070 (2023).

Howitt, D. & Cramer, D. Introduction to SPSS in Psychology: With Supplement for Releases 10, 11, 12 and 13 (Pearson, 2005).

Chidambaram, S., Karmegam, U., Prasanna, M. V. & Sasidhar, P. A study on evaluation of probable sources of heavy metal pollution in groundwater of Kalpakkam region, South India. Environmentalist 32, 371–382 (2012).

Kolsi, S. H., Bouri, S., Hachicha, W. & Dhia, H. B. Implementation and evaluation of multivariate analysis for groundwater hydrochemistry assessment in arid environments: a case study of Hajeb Elyoun-Jelma, Central Tunisia. Environ. Earth Sci. 70 (5), 2215–2224 (2013).

USEPA., (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Risk assessment guidance for superfund (RAGS), vol I: human health evaluation manual (Part E, supplemental guidance for dermal risk assessment) USEPA, Washington, DC. (2004).

USEPA., (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Exposure factors handbook ed (Final), (2011). Washington DC. https://www.epa.gov/expobox/exposure-factors-handbook-2011-edition

Wilbur, S. B., Hansen, H., Pohl, H., Colman, J. & McClure, P. Using the ATSDR guidance manual for the assessment of joint toxic action of chemical mixtures. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 18 (3), 223–230 (2004).

Chowdhury, U. K. et al. Groundwater arsenic contamination and human sufferings in West Bengal, India and Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. 83, 393–415 (2001).

ICMR., (Indian Council of Medical Research). Nutrient requirements and recommended dietary allowances for indians Hyderabad (India). Natl. Inst. Nutr. (2009).

De Miguel, E., Iribarren, I., Chacon, E., Ordonez, A. & Charlesworth, S. Risk-based evaluation of the exposure of children to trace elements in playgrounds in Madrid (Spain). Chemosphere 66 (3), 505–513 (2007).

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016 [OP]: Monitoring Health for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). World Health Organ. (2016).

Clarke, K. C. Analytical and computer cartography. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-033481-2. (1995).

Stafford, D. B. Civil engineering applications of remote sensing and geographic information systems. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). (1991).

Johnson, L. E. Geographic Information Systems in Water Resources Engineering (CRC, 2016).

Tiwari, A. K., Singh, P. K., Singh, A. K. & De Maio, M. Estimation of heavy metal contamination in groundwater and development of a heavy metal pollution index by using GIS technique. Bull. Environ. Contam. 96, 508–515 (2016).

Ozioko, O. H. & Igwe, O. GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using heuristic and bivariate statistical methods for Iva Valley and environs Southeast Nigeria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192, 1–19 (2020).

Ghosh, A., Bhattacharjee, S. & Bera, B. Hydro-Geomorphological Mapping of Manbhum-Singhbhum Plateau (Part of Singhbhum Protocontinent, India) for Water Resource Development and Landuse Planning. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 51 (8), 1757–1775 (2023).

BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards). Drinking water specifications, IS:10500, 2nd revision. New Delhi. (2012). http://law.resource.org/in/bis/S06/is.10500.2012.pdf

Dhakate, R. & Singh, V. S. Heavy metal contamination in groundwater due to mining activities in Sukinda valley, Orissa-a case studies. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 1 (4), 58–67 (2008).

Jain, C. K., Bandyopadhyay, A. & Bhadra, A. Assessment of ground water quality for drinking purpose, District Nainital, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 166, 663–676 (2010).

Giri, S., Mahato, M. K., Singh, G. & Jha, V. N. Risk assessment due to intake of heavy metals through the ingestion of groundwater around two proposed uranium mining areas in Jharkhand, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 184 (3), 1351–1358 (2012).

Neogi, B., Tiwari, A. K. & Singh, A. K. Groundwater geochemistry and risk assessment to human health in North Karanpura Coalfield, India. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management, 20,100897. (2023).

Singh, R. et al. Assessment of potentially toxic trace elements contamination in groundwater resources of the coal mining area of the Korba Coalfield, Central India. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 1–17 (2017).

Mahato, M. K., Singh, P. K., Tiwari, A. K. & Singh, A. K. Risk assessment due to intake of metals in groundwater of East Bokaro Coalfield, Jharkhand, India. Exp. Health. 8, 265–275 (2016).

Jayaprakash, M., Giridharan, L., Venugopal, T., Kumar, K., Periakali, P. & S.P. & Characterization and evaluation of the factors affecting the geochemistry of groundwater in Neyveli, Tamil Nadu, India. Environ. Geol. 54, 855–867 (2008).

Sahoo, S. & Khaoash, S. Impact assessment of coal mining on groundwater chemistry and its quality from Brajrajnagar coal mining area using indexing models. J. Geochem. Explor. 215, 106559 (2020).

Dhakate, R., Mahesh, J., Sankaran, S., Gurunadha & Rao, V. V. S. Multivariate statistical analysis for assessment of groundwater quality in Talcher Coalfield Area, Odisha. J. Geol. Soc. India. 82, 403–412 (2013).

Bharat, A. P., Singh, A. K. & Mahato, M. K. Heavy metal geochemistry and toxicity assessment of water environment from ib valley coalfield, India: implications to contaminant source apportionment and human health risks. Chemosphere 352, 141452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemo-sphere.2024.141452 (2024).

Nephalama, A. & Muzerengi, C. Assessment of the influence of coal mining on groundwater quality: Case of Masisi Village in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Proceedings of the Freiberg/Germany, Mining Meets Water- Conflicts Solutions, Leipzig, Germany, 11–15 (2016).

Bhuiyan, M. A., Islam, M. A., Dampare, S. B., Parvez, L. & Suzuki, S. Evaluation of hazardous metal pollution in irrigation and drinking water systems in the vicinity of a coal mine area of northwestern Bangladesh. J. Hazard. Mater. 179 (1–3), 1065–1077 (2010).

Zhang, S., Liu, G. & Yuan, Z. Environmental geochemistry of heavy metals in the groundwater of coal mining areas: a case study in Dingji coal mine, Huainan Coalfield, China. Environ. Forensics. 20 (3), 265–274 (2019).

Qiu, H. & Gui, H. Heavy metals contamination in shallow groundwater of a coal-mining district and a probabilistic assessment of its human health risk. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 25 (3), 548–563 (2019).

Sharma, D. A. et al. Distribution of uranium in groundwaters of Bathinda and Mansa districts of Punjab, India: inferences from an isotope hydrochemical study. J. Radioanal Nucl. Chem. 313 (3), 625–633 (2017).

Sharma, S., Nagpal, A. K. & Kaur, I. Appraisal of heavy metal contents in groundwater and associated health hazards posed to human population of Ropar Wetland, Punjab, India and its environs. Chemosphere 227, 179–190 (2019).

Agrawal, P., Mittal, A., Prakash, R., Kumar, M. & Tripathi, S. K. Contamination of drinking water due to coal-based thermal power plants in India. Environ. Forensics. 12 (1), 92–97 (2011).

Sahoo, M., Mahananda, M. R. & Seth, P. Physico-chemical analysis of surface and groundwater around talcher coal field. J. Geosci. Environ. Protect. 4, 26–37 (2016).

Li, K. et al. Spatial analysis, source identification and risk assessment of heavy metals in a coal mining area in Henan, Central China. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 128, 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ibiod.2017.03.026 (2018).

Jarup, L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 68, 167 182 (2003).

Needleman, H. Lead poisoning. Annu. Rev. Med. 55 (1), 209–222 (2004).

Lohse, J., Sander, K. & Wirts, M. Heavy Metals in Motor Vehicles 2. Report Compiles for the Directorate General Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection of the Commission of the European Communities (Okopol—Institut fur Ohkologie und Politik GmbH, 2001).

Sharheen, D. G. Contributions of urban roadway usage to water pollution. EPA-600/2-75-004 (1975).

Davis, A., Shokouhian, M. & Ni, S. Loading estimates of lead, copper, cadmium and zinc in urban runoff from specific sources. Chemosphere 44, 997–1009 (2001).

Ipeaiyeda, A. R. & &Dawodu, M. Heavy metals contamination of top soil and dispersion in the vicinities of reclaimed auto-repair workshops in Iwo, Nigeria. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiopia. 22 (3), 339–348 (2008).

Fishbein, L. Sources, transport and alterations of metal compounds: an overview. I. Arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, and nickel. Environ. Health Perspect. 40, 43–64 (1981).

USEPA., (US Environmental Protection Agency). Water Quality Criterion for the Protection of Human Health: Methylmercury Chap. 4: Risk Assessment for Methylmercury (EPA Office of Sciences and Technology, Office of Water, 2001).

USEPA., (US Environmental Protection Agency). Health Effect Assessments Summary Tables (HEAST) and user’s Guide (Office of Emergency and Remedial Response, 1989).

Ginsberg, G., Hattis, D., Miller, R. & Sonawane, B. Pediatric pharmacokinetic data: implications for environmental risk assessment for children. Pediatrics 113 (Supplement-3), 973–983 (2004).

Faustman, E. M., Silbernagel, S. M., Fenske, R. A., Burbacher, T. M. & Ponce, R. A. Mechanisms underlying children’s susceptibility to environmental toxicants. Environ. Health Persp. 108 (suppl-1), 13–21 (2000).

IARC., International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Supplement 7: overall evaluations of carcinogenicity: an updating of IARC monographs volumes 1 to 42. (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Vice Chancellor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and the Director of CSIR- Central Institute of Mining and Fuel Research, Dhanbad, for providing the research facilities. We thank Saurabh Kumar Singh and Suraj Kumar for their support during the sampling. One of the authors (Ashwani Kumar Tiwari) is grateful to the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India, for funding support. We sincerely thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India, under the start-up research grant (No. SRG/2022/000355).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.T. designed fieldwork, collected groundwater samples, conducted laboratory analysis and data interpretation, and conceptualised and prepared a draft manuscript. A.K.S. provided analytical support, and M.K.M. and S.G. helped during the analysis. S.G. helped estimate the risk to human health. M.K.M. S.G. and A.K.S edited the draft manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiwari, A.K., Giri, S., Mahato, M.K. et al. Anthropogenic influence on groundwater metal toxicity and risk to human health assessment in Umaria coalfield of Madhya Pradesh, India. Sci Rep 15, 12007 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88783-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88783-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ecological and health risk assessment of heavy metal pollution of sediments from artisanal mining in North Central Nigeria

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2025)