Abstract

With the fast growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and a novel generation of network technology, the Internet of Things (IoT) has become global. Malicious agents regularly utilize novel technical vulnerabilities to use IoT networks in essential industries, the military, defence systems, and medical diagnosis. The IoT has enabled well-known connectivity by connecting many services and objects. However, it has additionally made cloud and IoT frameworks vulnerable to cyberattacks, production cybersecurity major concerns, mainly for the growth of trustworthy IoT networks, particularly those empowering smart city systems. Federated Learning (FL) offers an encouraging solution to address these challenges by providing a privacy-preserving solution for investigating and detecting cyberattacks in IoT systems without negotiating data privacy. Nevertheless, the possibility of FL regarding IoT forensics remains mostly unexplored. Deep learning (DL) focused cyberthreat detection has developed as a powerful and effective approach to identifying abnormal patterns or behaviours in the data field. This manuscript presents an Advanced Artificial Intelligence with a Federated Learning Framework for Privacy-Preserving Cyberthreat Detection (AAIFLF-PPCD) approach in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. The AAIFLF-PPCD approach aims to ensure robust and scalable cyberthreat detection while preserving the privacy of IoT users in smart cities. Initially, the AAIFLF-PPCD model utilizes Harris Hawk optimization (HHO)-based feature selection to identify the most related features from the IoT data. Next, the stacked sparse auto-encoder (SSAE) classifier is employed for detecting cyberthreats. Eventually, the walrus optimization algorithm (WOA) is used for hyperparameter tuning to improve the parameters of the SSAE approach and achieve optimal performance. The simulated outcome of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique is evaluated using a benchmark dataset. The performance validation of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique exhibited a superior accuracy value of 99.47% over existing models under diverse measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

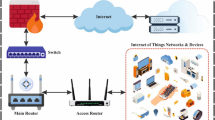

A maintainable smart city is a standard shift in urban improvement that controls communication technologies (ICTs) and the power of information to make a liveable, more efficient, and urban environment-friendly1. By incorporating several technological developments, like data analytics, renewable energy solutions, and IoT devices, smart, maintainable cities intend to improve the living standard for residents while reducing the negative impact on the environment. The main aim of a maintainable smart city is to enhance the effectiveness of urban services and operations2. Utilizing ICTs, cities can improve transportation systems, waste management, resource allocation, and energy consumption. The smart city method contains a sensing layer and data analytical process to recognize the real-world patterns of the city services in dissimilar regions like energy, transport, health, environment, and waste management3. Ensuring security in smart cities means sustaining data and the lattice from any evil actions and threats. Cyber-security of hardware and software made for smart cities is not usually considered by their vendors. Thus, using such insecure products can lead to the method being filled with fake data, malfunctioning through hacking, and the system being stopped4. To address these problems, this work investigates the impossibility of FL for privacy-preserving cyberthreat detection, which, as far as we know, is one of the innovative contributions. As a distributed learning model, FL is familiar with numerous privacy-sensitive fields, such as the next-word prediction task and medical imaging understanding in virtual keyboards5. In this nutshell, FL permits distributed clients (data owners) to collectively train a machine learning (ML) approach without exposing their local datasets to some parties. Figure 1signifies the architecture of FL6.

Despite attaining encouraging performance outcomes in some privacy-sensitive ML tasks, FL is also vulnerable to adverse ML attacks, particularly poisoning assaults. In this case, FL methods have exposed encouraging outcomes in achieving large-scale datasets from different IoT devices, providing a possible path forward7. Developing the current investigation is pivoting to the DL and ML methods to avoid these restrictions. Many applications and IoT services with ML-based methods are emerging in massive regions such as healthcare, object monitoring, transport, security, surveillance, and control. DL approaches provide critical essential services and strong security methods to protect IoT devices, and preventive security designs have been consistent with implementation errors and inadequate activity approaches, as threats were unavoidable8. Furthermore, conventional cyberattack detection provides a fight with the ‘high-dimensional curse’ after handling higher-dimensional IoT data streams. It results in enhanced computational cost and decreased detection precision. The heterogeneous nature of IoT devices also offers novel challenges regarding model generalization and data standardization9. The rapid advancement of technology has created new opportunities for improving urban living through interconnected systems and effectual resource management. However, as smart cities become more dependent on the IoT and data analytics, the requirement for robust security and privacy measures has become increasingly critical. The challenge is safeguarding sensitive data while maintaining the performance of smart city services. FL, paired with advanced AI techniques, presents a promising approach to improving cybersecurity by enabling collaborative learning without compromising privacy. This approach confirms that smart city infrastructures remain secure, effectual, and sustainable as they evolve10.

This manuscript presents an Advanced Artificial Intelligence with a Federated Learning Framework for Privacy-Preserving Cyberthreat Detection (AAIFLF-PPCD) approach in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. The AAIFLF-PPCD approach aims to ensure robust and scalable cyberthreat detection while preserving the privacy of IoT users in smart cities. Initially, the AAIFLF-PPCD model utilizes Harris Hawk optimization (HHO)-based feature selection to identify the most related features from the IoT data. Next, the stacked sparse auto-encoder (SSAE) classifier is employed for detecting cyberthreats. Eventually, the walrus optimization algorithm (WOA) is used for hyperparameter tuning to improve the parameters of the SSAE approach and achieve optimal performance. The simulated outcome of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique is evaluated using a benchmark dataset. The major contribution of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique is as follows:

The AAIFLF-PPCD model introduces a novel feature selection mechanism based on HHO to improve cyberthreat detection performance. This approach improves the model’s efficiency by choosing relevant features and reducing dimensionality. Additionally, it optimizes the detection process, resulting in improved accuracy and faster response times when detecting cyberthreats.

The AAIFLF-PPCD technique employs an SSAE classifier to identify and detect cyberthreats accurately. This classifier captures intrinsic patterns in cyberattack data, improving detection performance. The model also improves the approach’s capability to distinguish between normal and malicious behaviours, enhancing overall security efficiency.

The AAIFLF-PPCD approach integrates the WOA model for hyperparameter tuning to enhance classifier performance. This optimization method fine-tunes the model’s parameters, confirming more accurate and effective threat detection. By utilizing WOA, the model adapts to dynamic cyberthreat patterns, improving its overall detection capabilities.

The novelty of the AAIFLF-PPCD model is its integration of HHO for feature selection, SSAE for classification, and WOA for hyperparameter optimization. This unique combination improves the model’s capability to detect cyberthreats more accurately and efficiently. By incorporating these advanced techniques, the model utilizes optimized features, refined classification, and improved performance, providing a robust solution for cyberthreat detection in dynamic environments.

Literature survey

Khan et al.11introduced a privacy-preserving FL-based IDS approach called Fed-Inforce-Fusion. In particular, the presented Fed-Inforce-Fusion approach utilizes reinforcement learning methods for learning the latent relationships of healthcare information. Then, an FL-based approach is designed. Subsequently, aggregation or fusion tactics are utilized. Thantharate and Anurag12proposed Cybria, an FL architecture for collective cyberthreat recognition without negotiating sensitive information. The decentralization method training methods on local data dispersed over clients and divides just intermediary method upgrades to produce a combined global method. This research additionally advanced an FL framework designed to preserve privacy and preserve intrusion detection. In13, a primarily executed Capsule Network (CapsNet) has been proposed. Then, the Quantum Key Secure Communication Protocol (QKSCP) was additionally applied. Afterwards, the Dual Q Network-based Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic method (DQN-A3C) model prevents and detects assaults. Finally, the understandable DQN-A3C technique and the Siamese Inter Lingual Transformer (SILT) transformer were utilized for natural language representation. Lastly, an FL-based knowledge-transfer method, recognized as global risk evaluation, is generated among the Cyber Threat Repository (CTR) and cloud servers. Alqurashi14 implemented a new hybrid FL architecture using a multi-party communication (FLbMPC) approach. This method contains four stages: data aggregation, standardization and data collection, attack detection, and model training. FL has been applied to train the local methods of all IoT devices using their corresponding subsets of data. The MPC model has been applied to aggregate the encoded local methods globally. Lastly, in the attack recognition stage, the global approach compared real-world sensor data and forecast values for identifying cyberattacks. Park et al.15 developed a PoAh-enabled FL structure for DDoS attack detection in IoT systems. FL has been applied at the federated layer for privacy preservation to mitigate the negative influences needed for stability, accuracy, low latency, and fast processing. Furthermore, blockchain (BC) technology has been applied at the authentication layer with PoAh to guarantee data validation, authentication, performance, and higher security in IoT systems.

Djenouri and Belbachir16 discover cutting-edge pipelines that combine federated DL using trusted authorities’ methods. An enhanced Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) approach was proposed to efficiently recognize intrusions and anomalies inside the system. Moreover, an intelligent swarm optimization (ISO) solution is presented to tackle dimension-reducing problems. Detailed assessments of the FL-based methods are performed by applying the famous NSL-KDD database. Gaba et al.17presented a new vertical federated multi-agent learning architecture. This model uses synchronous DQN-based agents in stationary settings, enabling convergence to optimum tactics. Rawat and Kumar18recommended a decentralized structure containing a chain of Federated blocks at every edge device using a cohere-consensus mechanism (FBCC). This architecture utilizes BC technology to update local techniques or store global techniques. The work also emerged using a new cohere-consensus mechanism to enable the recommended FBCC, effectively reducing the amount of consensus calculating while concurrently reducing the threat of malicious attacks. Jain, Tihanyi, and Ferrag19 explore security challenges in integrating DL techniques in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), focusing on risks like adversarial attacks and data privacy breaches while highlighting the requirement for novel security solutions to improve system robustness and trustworthiness. Kumar et al.20 integrate a BC-based AKA mechanism with explainable AI (XAI) for securing smart city consumer applications. The technique confirms secure communication between entities utilizing BC and employs SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the key features influencing decisions. Kumar et al.21 propose a DL and BC-based case study for secure data sharing in ZTNs, featuring a variational autoencoder (VAE) and attention-based gated recurrent units (AGRU)-based IDS and a novel authentication protocol using BC, ECC, smart contracts, and PoA consensus. Kumar et al.22 address security and privacy in CIoT-inspired Metaverse, explore the role of XAI and BC, and present future research directions for building the Metaverse.

Satpathy et al.23 analyze the performance of integrating Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) and LSTM with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in a FL framework to reduce data dimensionality while preserving key values. Myrzashova et al.24 introduce an innovative framework that leverages BC-based FL, ensuring the preservation of privacy and security. Prince et al.25 assess the security of IoT devices, focusing on integrating IEEE Standards with DL techniques. Kollu et al.26 present a novel intrusion detection method using federated graphical authentication and cloud-based smart contracts in FinTech. Zhang et al.27 propose a research and application framework for trusted data circulation in the food industry, utilizing BC and FL to enhance data security, utilization, and processing efficiency. Tauseef et al.28 explore the integration of BC and AI to improve the security of IoT networks, focusing on their complementary roles in ensuring data confidentiality, integrity, and anomaly detection. Alamro et al.29 present an Advanced Ensemble Transfer Learning for Cyberthreat Detection in Low Power Systems (AETL-CDLPS) model by using linear scaling normalization (LSN) for data normalization, improved coati optimization algorithm (ICOA) for feature selection and an ensemble of gated recurrent unit (GRU), deep convolutional neural network (DCNN), and SSAE classifiers, optimized by Bayesian Optimization (BOA). Bashir et al.30 explore the adoption of IoT technology in Maritime Transportation Systems (MTSs). It discusses real-time tracking, cargo handling, maintenance, route optimization, and fuel consumption in MTSs, focusing on future applications and advancements. Hassan et al.31 introduce FLLSTM Trust-aware Location-aided Routing (FLSTMT-LAR), a framework combining FL, LSTM-based trust prediction, and multiobjective optimization for secure, efficient, and low-latency routing in IoT networks while preserving privacy. Bac et al.32 explore the use of AI and XAI for cybersecurity in Smart Manufacturing in Industry 5.0, highlighting XAI’s role in anomaly detection within Industrial Control Systems. Malik et al.33 incorporate FL and BC to enhance Healthcare IoT analytics and security, ensuring data privacy and preventing manipulation while complying with strict healthcare regulations.

The limitations of the existing studies in this domain include the high computational cost and complexity associated with integrating BC, FL, and AI, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Additionally, privacy and security concerns still pose significant challenges, as data sharing across distributed systems remains vulnerable to attacks. Furthermore, many existing approaches lack sufficient explainability, making it difficult for security analysts to trust the automated decision-making processes. Another gap is the limited scalability of some proposed solutions when applied to large-scale, real-world systems. Future research should improve these techniques’ efficiency, scalability, and interpretability while addressing the evolving cybersecurity threats in IoT and other applications.

Materials and methods

This manuscript presents the AAIFLF-PPCD method in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. The primary focus of the AAIFLF-PPCD method is to ensure robust and scalable cyberthreat detection while preserving the privacy of IoT users in smart cities. To accomplish that, the AAIFLF-PPCD model contains three stages: HHO-based feature selection, SSAE-based attack recognition, and WOA-based hyperparameter tuning. Figure 2 illustrates the flow of the AAIFLF-PPCD model.

Stage I: feature selection using HHO

Firstly, the AAIFLF-PPCD model utilizes HHO-based feature selection to identify the most related features from the IoT data34. This method is chosen due to its ability to replicate Harris hawks’ collaborative hunting behaviour, balancing exploration and exploitation. This method is advantageous in handling high-dimensional datasets, as it effectually chooses the most relevant features while discarding irrelevant ones, improving both model accuracy and computational efficiency. Compared to other optimization techniques like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) or Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), HHO presents faster convergence and more precise feature subsets. Moreover, the capability of the HHO model to avoid local optima makes it a robust choice for complex, non-linear feature selection tasks. The technique improves the overall performance of ML models, specifically in cyberthreat detection, by improving the quality of input features and reducing overfitting. Figure 3 illustrates the steps involved in the HHO model.

HHO replicates the Harris hawk’s predatory behaviour over three stages: the exploration stage, replicating the behaviour of hawks before searching; the transitional stage between exploitation and exploration, replicating the transition from hunting for prey to starting the search; and the exploitation stage, reflect the hawks’ particular behaviours throughout the searching method.

Exploration stage

The exploration stage mimics HH’s monitoring, waiting, and tracking behaviours in the initial searching phases. To arrest prey, HH has to wait for the prey’s arrival in the patient. In the exploration stage, HH’s location is decided by (1).

Meanwhile, \(\:q\) means randomly generated numbers among \(\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) and defines the dual tracking approaches of HH. If \(\:q\ge\:0.5\), HHs lay on an arbitrary tree; if \(\:q<0.5,\) HHs perch follow the location of another prey and hawk.

The location vectors of the HH in the \(\:tth\) and the \(\:t+1\) iteration are \(\:X\left(t\right)\) and \(\:\left(t+1\right)\), correspondingly. The arbitrary location vector is \(\:{X}_{rand}\left(t\right)\), and the average location vector of every HH is \(\:X\left(t\right)\). \(\:UB\) and \(\:LB\) signify the upper and lower limitations of the search space. \(\:{r}_{1},{r}_{2},{r}_{3}\), and \(\:{r}_{4}\) are randomly generated values isolated in the range\(\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\). N can mean the entire hawk count\(\:.\)

Transition between exploitation and exploration

An HH can transition between positions according to its prey’s escaping feature (signified by \(\:En\)). Notably, \(\:En\) is reduced in the escaping process.

Whereas \(\:En\) refers to the prey’s escape feature, and \(\:E0\) means the emerging escape feature of the prey. If the target needs to seepage from the HH, using the consumption of bodily strength, the escaping feature will be released slowly. According to the value of \(\:En\), when \(\:\left|En\right|\ge\:1\), it arrives at the exploration stage, and the HH defines the prey location by searching several regions in the search interval. When \(\:\left|En\right|<1\), it arrives at the exploitation stage, and the HH assaults the prey discovered during the exploration stage.

Exploitation stage

During this stage, the HH finds its prey and strikes it. This HHO model provides four attack methods according to how that victim escaped and the HH’s tactic to hunt its prey. Based on the dimensions of \(\:En\), the HH accepts dual tactics: hard and soft siege. If \(\:\left|En\right|\ge\:0.5\) and \(\:\left|En\right|<0.5,\) the HH accepts soft and hard siege. The randomly formed number \(\:r\) characterizes the likelihood that the prey would escape from the unsafe surroundings once the HH presents an unexpected attack. \(\:r\) is isolated equally in the range \(\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\). If \(\:r<0.5\), it successfully escapes the prey. Otherwise, it fails to take flight.

-

Tactic 1: Soft Siege.

If \(\:r\ge\:0.5\) and \(\:\left|En\right|\ge\:0.5\), the prey’s escaping feature is relatively large; hence, it attempts to escape from unsafe surroundings by jumping arbitrarily. The instruction in Eq. (4) imitates the behavioural model.

Here, \(\:Ju\) means randomly generated number consistently spread at the interval\(\:\left(\text{0,2}\right)\), which specifies the random leaping level in the prey’s escape \(\:\varDelta\:X\left(t\right)\) represents abnormality between the prey location vector and an HH location vector within the \(\:{t}^{th}\) iterations in Eq. (5).

-

Tactic 2: Hard Siege.

The prey escaping feature is insufficient if r ≥ 0.5 and 1En |<0.5. Currently, the HH presents the hard siege on prey for the following assaults expressed in Eq. (6).

-

Tactic 3: soft besiege followed by advanced fast dives.

If \(\:r<0.5\) and \(\:\left|En\right|\ge\:0.5\), the escape feature of the prey is enough. The computation equations are as shown:

Here, \(\:LF\) refers to Levy Flight, \(\:u\) and \(\:v\) are randomly generated numbers distributed evenly in the range\(\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\), \(\:p\) means 1.5, and \(\:Dim\) displays the problem’s dimension, which must be resolved.

-

Tactic 4: hard besiege followed by advanced swift dives.

If \(\:r<0.5\) and \(\:\left|En\right|<0.5\), the HH makes a robust encirclement before the \(\:raid\) and then drops the mean distance from the prey. This allows the prey to escape, whereas the escape feature is insufficient. The computation equations are as shown:

The HHO method combines the goals into an objective equation such that a current weight recognizes all objective importance. This paper utilizes the fitness function (FF), which incorporates both FS goals as demonstrated in (15).

Whereas \(\:Fitness\left(X\right)\) characterizes the fitness value of a subset\(\:\:X,\)\(\:E\left(X\right)\) symbolizes the classifier rate of error by utilizing the chosen features in the subset\(\:\:X\), \(\:\left|R\right|\) and \(\:\left|N\right|\) represent selected feature counts and the original feature counts in the dataset individually, \(\:\beta\:\) and \(\:\alpha\:\) denotes weights of the reduction ratio and the classifier error, \(\:\beta\:=(1-\alpha\:)\) and\(\:\:\alpha\:\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\).

Stage II: attack classification using SSAE

Next, the SSAE classifier is employed for detecting cyberthreats35. This technique is a powerful model for attack classification due to its ability to learn hierarchical, abstract representations of data through deep architecture while maintaining sparsity. This sparsity enables SSAE to effectually capture important features in high-dimensional datasets, which is crucial for accurately detecting subtle attack patterns. Compared to conventional classifiers like decision trees or support vector machines, SSAE outperforms handling complex, unstructured data and is less prone to overfitting. The DL structure of the model allows it to automatically learn relevant features without extensive feature engineering, mitigating the manual intervention required. The capability of the SSAE model to detect anomalies and classify attacks in large-scale cybersecurity datasets makes it highly appropriate for real-time intrusion detection systems. Furthermore, SSAE is more resilient to noise, which improves its reliability in dynamic, evolving attack scenarios. Figure 4 portrays the structure of SSAE.

Auto-encoder (AE) is a single HL neural network (NN) with an encoder and decoder. It comprises a HL, an output, and an input layer. The input sample image \(\:X=\left[{x}_{1},{x}_{2}{\cdots\:,\:x}_{m}\right]\) is utilized, whereas \(\:m\) denotes the system’s training sample counts. The encoding maps the input data to a concealed representation \(\:h\). Next, the decoding maps the concealed representation \(\:h\) to a rebuilt output \(\:z\). These dual stages are described as:

Here, \(\:{b}_{1}\) and\(\:\:{w}_{1}\) represent the biases and weights of the encoder layer, \(\:{b}_{2}\) and\(\:{\:w}_{2}\) correspondingly represent the decoder layer’s biases and weights. The \(\:f\left(\bullet\:\right)\) and \(\:g\left(\bullet\:\right)\) are mappings. Conventional AE can update functions; now, they are sigmoid functions \(\:(1+\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}(-x){)}^{-1}\). Conventional AE can update the parameters \(\:\theta\:=\{{W}_{1},{b}_{1},{W}_{2},{b}_{2}\}\) by reducing the loss function \(\:J\left(W,b\right)=\frac{1}{\text{m}}{\sum\:}_{t=1}^{m}\frac{1}{2}{\left(\parallel{x}_{i}-{z}_{i}\parallel\right)}^{2}\), representing an error in the output and input data reconstruction.

The SAE is an NN method that presents a sparsity limitation on the conventional AE. This limitation removes more important features by limiting the activation elements in the HL, making the activation of the concealed components sparser. Specifically, by presenting a sparsity restriction, most concealed representation nodes are saved hidden, and just smaller ones are stimulated. When the sigmoid activation function is selected, an output near 0 represents that the node is inactive, while an output close to 1 indicates that the node is active.

Assumed that\(\:\:{a}_{j}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) refers to the activation value of concealed neuron \(\:j\), and \(\:{a}_{j}\left({x}_{i}\right)=f\left({W}_{j}{x}_{i}+{b}_{j}\right)\). Next, the average activation is described as:

To encounter the sparsity state, the average activation value \(\:\widehat{\rho\:}\) of the HL neurons is limited to a p-value near zero by adding a sparse penalty factor. This term is stated as:

While \(\:\beta\:\) denotes the sparsity penalty term, which can typically be a value among \(\:(0\),1), and \(\:s\) represents the size of the HL. \(\:KL\left(\rho\:\right|\left|{\widehat{\rho\:}}_{j}\right)\) denotes Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which is applied to penalize the change between the actual and estimated distributions.

SSAE is a DL approach that associations the stacked AE with the sparse AE with a sparsity limitation. This method could learn higher-level data characteristics by stacking numerous sparse AE layer by layer while presenting sparsity limitations to remove more explanatory characteristics. For every HL \(\:l\in\:\left\{\text{1,2},\cdots\:,\:D\right\}\) of the SSAE, and \(\:D\) refers to the total layer value. \(\:{h}^{l}=f\left({W}^{l}{h}^{l-1}+{b}^{l}\right)\) means layer output value \(\:l\). According to the architecture of the SGAE in the earlier section, a 2-layer SSAE is utilized here. As a result, the last SSAE loss function is described as:

While \(\:\beta\:\) denotes the parameter in balancing the dissimilar penalty factors of the loss function.

Stage III: hyperparameter tuning

Eventually, the WOA is used for hyperparameter tuning to enhance the parameters of the SSAE technique and achieve optimal performance36. This model is chosen because it can explore the solution space efficiently and avoid local optima. WOA replicates the social behaviours of walruses, which allows it to balance exploration and exploitation, resulting in robust optimization results. Unlike conventional optimization methods like grid or random search, WOA needs fewer iterations and computational resources while providing high-quality solutions. Its versatility in adapting to diverse problems makes it appropriate for fine-tuning complex ML models, particularly in cybersecurity tasks where high accuracy is critical. WOA is valuable for optimizing hyperparameters for DL models, like the SSAE, ensuring optimal performance. The fast convergence and efficiency of the algorithm in high-dimensional search spaces make it an ideal choice over more conventional optimization techniques.

WO has been categorized as a swarm-based meta-heuristic optimizer method stimulated by the social behaviours of walruses in breeding, roosting, foraging, and migrating. The walrus is the largest aquatic animal, apart from whales. The walrus has dual characteristics that help it in several activities for self-defence and survival. Using these safety and danger signals, WO incorporates the exploitation and exploration stages, thus equaling the exchange between initial convergence and avoiding capture in local bests. Moreover, the WO population’s behaviour imitates the walrus herd’s roosting behaviour, which is dissimilar in juveniles, males, and females, whereas they update their locations. The optimizer processes of the presented WO have been carried out in 4 stages: initialization, making of safety and danger signals, exploitation (reproduction), and exploration (migration).

Initialization

The WO’s modelling starts with a group of early arbitrary bounded solutions (\(\:S\)), which help as the initial population matrix (\(\:S\)).

Whereas \(\:N\) denotes the size of the population; \(\:dim\) characterizes the decision variable’s dimension in all solution vectors \(\:\left({S}_{i}\right)\); \(\:{s}_{i}^{j}\) represents the \(\:{j}^{th}\) decision variable in the \(\:{i}^{th}\) solution; \(\:{s}_{i,\:\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}^{j}\) and \(\:{s}_{i,\:\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}^{j}\) represent upper and lower limits of \(\:{s}_{i}^{j}\), and \(\:rand\) refers to the randomly generated number in the interval of \(\:\left[\text{0,1}\right].\) All candidate solutions contain their fitness value \(\:\left({F}_{i}\right)\), organized in the succeeding vector:

90% of the WO population (walrus group) comprises adults, dispersed correspondingly among females and males. The residual 10% of walruses are measured to be juveniles. All candidates’ solutions constantly updated their locations within the searching area through iteration that followed the tactics considered in the following stages.

Producing safety and danger signals

During the WO population, some walruses help monitor as guards. The group’s direction is described and impacted by presenting danger alerts when sudden environments are discovered. During WO, the following descriptions are expressed to describe these double type of signals, such as danger and safety signals, which play an essential part in the balance between exploitation and exploration:

Here, \(\:A\) and \(\:R\) characterize coefficients of danger; \(\:\alpha\:\) means the descending factor that reduces from (1-\(\:0\)) through iterations, \(\:k\) and \(\:i{t}_{-}\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}\) is, correspondingly, the iteration amount and the maximal pre-defined iteration counts; and \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are randomly generated numbers in the interval of \(\:\left[\text{0,1}\right].\)

Exploration (Migration)

If danger signals are incredibly high, more than a particular pre-defined level, the walrus group must migrate to other, suitable regions for survival. During WO, this method can take place in the initial phase of the technique, giving a chance to maximize the global hunt. Therefore, the location of all solutions in the population of WO would be upgraded as shown:

Now \(\:{S}_{i}^{k+1}\) and \(\:{S}_{i}^{k}\) are the novel and present locations of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) solution vector; \(\:migratio{n}_{-}step\) means walrus motion’s step length; \(\:{S}_{m}^{k}\) and \(\:{S}_{u}^{k}\) mean dual solution vectors selected at random from the group at \(\:{k}^{th}\) iterations, representative vigilantes within the group; \(\:\beta\:\) characterizes the migrating stage controller coefficient changing quickly through iterations; and \(\:{r}_{3}\) stands for randomly generated numbers in the interval of \(\:\left[\text{0,1}\right].\)

Exploitation (Reproduction)

On the contrary, in the migration stage, the walrus group tends to reproduce in its present region rather than migrate if the dangers are lower. According to the safety signal level, the reproduction phase might be separated into two major activities: foraging underwater and roosting onshore. This activity will likely occur late during WO, presenting a chance for maximizing local search. The mathematics approaches demonstrating both actions are as follows:

Behavior of roosting

This behaviour has three major types of the population of WO— juveniles, males, and females in the walrus group updated their locations in 3 distinct ways. Halton sequence distribution has been accepted to reallocate the solution vector associated with male walruses arbitrarily. This novel location of the female walrus is targeted through the male walrus \(\:\left(Mal{e}_{i}^{k}\right)\) and the walrus in the leader \(\:\left({S}_{best}^{k}\right)\). During the system’s development, the female walrus was compelled by the lead rather than the mate.

Whereas \(\:Pemal{e}_{i}^{k+1}\) and \(\:Pemal{e}_{i}^{k}\) represent the novel and present locations of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) female walrus, \(\:Mal{e}_{i}^{k}\) refers to the present location of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) male walrus. Then, juvenile walruses are required to alter their location to prevent predators.

Here, \(\:Juvenil{e}_{i}^{k+1}\) and \(\:Juvenil{e}_{i}^{k}\) represent novel and present locations of the \(\:{i}^{ih}\) juvenile walrus, individually; \(\:P\) embodies the suffering feature of the juvenile walrus, has arbitrary values in the interval of \(\:0\) and \(\:1\) represents securer locations; and \(\:LF\) denotes a randomly generated vector based-on the Lévy function.

Now, \(\:g\) and \(\:h\) characterize dual variables taking a normal distribution, \(\:\left(0,{\sigma\:}_{g}^{2}\right),hN\left(0,{\sigma\:}_{h}^{2}\right)\).

Here, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{g}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{h}\) represent standard deviations.

Foraging behavior

Gathering and fleeing activities are the two major types of foraging underwater. Then, walruses would escape predators to other safer places underwater. WO imitates these behaviours mostly in late iterations.

Now, \(\:\left|{S}_{besi}^{k}-{S}_{i}^{k}\right|\) refers to the distance between the current walrus and the leader walrus, and \(\:{r}_{4}\) means randomly generated number in the interval\(\:\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\). In the collection activity, walruses updated their locations to identify sea areas with incredible food accessibility by distributing data and collaborating with other walruses within the group. These techniques help attain development in local exploitation and gain the optimal conceivable solution in a particular region in the searching area.

Here, \(\:{S}_{1}\) and \(\:{S}_{2}\) are dual-weighting vectors affecting the collecting activity of the herd; \(\:{S}_{second}^{k}\) signifies the present location of the second walrus; \(\:\left|{S}_{second}^{k}-{S}_{i}^{k}\right|\) characterizes the distance between the next and the present walrus; \(\:a\) and \(\:b\) represent gathering coefficients; \(\:\theta\:\) contains a value from \(\:(0\)-\(\:\pi\:)\), and \(\:{r}_{5}\) signifies randomly generated number in the interval of \(\:\left[\text{0,1}\right].\)

Fitness selection is an important feature that manipulates performance in the WOA. The hyperparameter choice procedure consists of the solution encoder method to assess the efficacy of the candidate solutions. In this paper, the WOA considers precision as the primary condition to model the FF, expressed as demonstrated.

Here, TP characterizes the true positive, and FP signifies the false positive value.

Result analysis and discussion

The experimental outcome of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique is verified under the Kaggle dataset37. The dataset contains 30,000 instances under 12 classes, as revealed in Table 1. The total number of features is 65, but only 32 have been selected.

Figure 5 demonstrates the correlation matrix of the AAIFLF-PPCD model. The figure illustrates the correlations between various network parameters, such as Scr_port, Des_port, byte_rate, anomaly_alert, total_packet, total_bytes, File_activity, and Process_activity. Scr_port and Des_port exhibit a negative correlation of −0.04, indicating a weak inverse relationship. byte_rate shows a slight negative correlation with Scr_port (−0.09) and Des_port (−0.03), with a minor positive correlation of 0.05 with anomaly_alert. total_packet portrays weak negative correlations with other variables, and total_bytes has a more significant positive correlation (0.23) with total_packet. File_activity and Process_activity share a robust positive correlation of 0.93, implying their robust association in network behaviour. Additionally, other variables like total_bytes, File_activity, and Process_activity exhibit weak correlations with the other features in the matrix. The results identify that the AAIFLF-PPCD model has effectual prediction of all classes accurately.

Figure 6 signifies the relationships between network parameters such as total_bytes, total_packet, anomaly_alert, byte_rate, Des_port, Scr_port, File_activity, and Process_activity. For instance, total_bytes and total_packet have a strong positive correlation of 0.75, illustrating that one growth is associated with an increase in the other. Anomaly_alert exhibits a weak correlation with the different parameters, with the highest being 0.50 with Scr_port. A positive correlation of 0.50 between byte_rate and total_bytes suggests that as byte_rate increases, total_bytes also tend to rise. File_activity and Process_activity exhibit a seamless positive correlation of 1.0, signifying a close relationship between these variables. Additionally, diverse attack types such as Generic_scanning, scanning vulnerability, Exfiltration, and Insider_malicious are identified, reflecting various cybersecurity threats detected from the visualized data.

Figure 7 presents the classifier outcomes of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique under 80%TRPH and 20%TSPH. Figure 7a and b illustrates the confusion matrices with correct identification and classification of all classes. Figure 7c demonstrates the PR analysis, implying higher performance through all classes. Eventually, Fig. 7d represents the ROC study, signifying proficient results with great ROC values for several classes.

Table 2; Fig. 8 depict the classifier outcomes of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 80%TRPH and 20%TSPH. The outcomes indicate that the AAIFLF-PPCD approach correctly identified the samples. With 80%TRPH, the AAIFLF-PPCD approach provides average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:{F1}_{score}\), and \(\:{AUC}_{score}\)of 99.47%, 97.20%, 96.84%, 96.92%, and 98.28%, respectively. Moreover, with 20%TSPH, the AAIFLF-PPCD model provides average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:{F1}_{score}\), and \(\:{AUC}_{score}\)of 99.43%, 96.94%, 96.55%, 96.66%, and 98.12%, respectively.

Figure 9 depicts the training (TRA) \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) and validation (VAL) \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) performances of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 80%TRPH and 20%TSPH. The \(\:acc{u}_{y}\:\)values are computed over a range of 0–25 epochs. The figure emphasizes that the TRA and VAL \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) values show growing tendencies, notifying the capabilities of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique with enhanced performance through multiple iterations.

Figure 10 shows the TRA loss (TRALOS) and VAL loss (VALLOS) graph of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 80%TRPH and 20%TSPH. The loss values are computed across a range of 0–25 epochs. The TRALOS and VALLOS values represent a decreasing trend, which notifies the proficiency of the AAIFLF-PPCD method in harmonizing an equilibrium among data fitting and generalization.

Figure 11 exhibits the classifier outcomes of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 70%TRPH and 30%TSPH. Figure 11a and b displays the confusion matrices with correct identification and classification of all class labels. Figure 11c displays the PR outcome, specifying enhanced performance through all classes. Finally, Fig. 11d exemplifies the ROC outcome, demonstrating proficient results with better ROC values for different classes.

Table 3; Fig. 12 demonstrate the classifier results of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 70%TRPH and 30%TSPH. The outcomes indicate that the AAIFLF-PPCD approach correctly identified the samples. With 70%TRPH, the AAIFLF-PPCD approach presents average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:{F1}_{score}\), and \(\:{AUC}_{score}\)of 99.18%, 95.11%, 95.10%, 95.10%, and 97.33%, respectively. Additionally, with 70%TRPH, the AAIFLF-PPCD technique presents average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:{F1}_{score}\), and \(\:{AUC}_{score}\)of 99.25%, 95.51%, 95.53%, 95.52%, and 97.56%, respectively.

Figure 13 shows the TRA and VAL \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) performances of the AAIFLF-PPCD methodology under 70%TRPH and 30%TSPH. The \(\:acc{u}_{y}\:\)values are computed through an interval of 0–25 epochs. The figure highlighted that the TRA and VAL \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) values display increasing tendencies, notifying the proficiency of the AAIFLF-PPCD model with superior performance above numerous iterations.

Figure 14 shows the TRALOS and VALLOS graph of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach under 70%TRPH and 30%TSPH. The loss values are computed across a range of 0–25 epochs. The TRALOS and VALLOS values show a decreasing trend, which notifies the competency of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique in harmonizing an equilibrium among data fitting and generalization.

Table 4; Fig. 15analyze the comparative results of the AAIFLF-PPCD model with the recent techniques20,21,22,38,39,40. The results underlined that the SVM, KNN, MLP, CNN + GRU, HZDA-5G IIoT, and PSO Ensemble models have reported worse performance. In the meantime, the IRMOFNN-AD model has gained closer outcomes with improved \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:acc{u}_{y},\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:\:{F1}_{score}\) of 95.33%, 95.33%, 99.10%, and 95.45%, respectively. Additionally, the AAIFLF-PPCD approach reported enhanced performance with superior \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\)\(\:acc{u}_{y},\:{and\:F1}_{score}\) of 97.20%, 96.84%, 99.47%, and 96.92%, respectively.

In Table 5; Fig. 16, the comparative analysis of the AAIFLF-PPCD approach is identified in terms of processing time (PT). The results suggest that the AAIFLF-PPCD model accomplishes more excellent performance. Based on PT, the AAIFLF-PPCD model presents lesser PT of 4.51s, demonstrating its superior efficiency in PT. In comparison, the SVM, KNN, MLP, CNN + GRU, HZDA-5G IIoT, PSO Ensemble, IRMOFNN-AD, XAI, SHAP, VAE, and AGRU methods attain improved PT values of 11.93s, 15.58s, 10.54s, 14.49s, 9.80s, 8.21s, 7.95s, 8.50s, 9.18s, 9.77s, and 10.32s, subsequently. This highlights the significant advantage of the AAIFLF-PPCD model in terms of processing time, making it a more time-efficient choice for cyberthreat detection in comparison to traditional and advanced methods.

Conclusion

This manuscript presented the AAIFLF-PPCD model in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. The AAIFLF-PPCD model concentrated on ensuring robust and scalable cyberthreat detection while preserving the privacy of IoT users in smart cities. Initially, the AAIFLF-PPCD model involved three stages: HHO HHO-based feature selection, SSAE-based attack detection, and WOA-based hyperparameter tuning. Primarily, the AAIFLF-PPCD model utilized HHO-based feature selection to identify the most related features from the IoT data. Next, the SSAE classifier was employed to detect cyberthreats. Eventually, the WOA was used for hyperparameter tuning to enhance the parameters of the SSAE method and achieve optimal performance. The simulated outcome of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique was evaluated using a benchmark dataset. The performance validation of the AAIFLF-PPCD technique exhibited a superior accuracy value of 99.47% over existing models under diverse measures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/munaalhawawreh/xiiotid-iiot-intrusion-dataset.Code Availability Statement: The source code developed and used in this study is available upon reasonable request. Researchers interested in accessing the code may contact the corresponding author at [mragab@kau.edu.sa].

References

Bandera, N. H., Arizaga, J. M. M. & Reyes, E. R. Assessment and prediction of chronic kidney using an improved neutrosophic artificial intelligence model. Int. J. Neutrosophic Sci., (1), (2023). pp.174 – 74.

Ding, S., Tukker, A. & Ward, H. Jun., Opportunities and risks of internet of things (IoT) technologies for circular business models: a literature review. J. Environ. Manag, 336, (2023). Art. 117662.

Rajawat, A. S. et al. Anomalies detection on attached IoT device at cattle body in smart cities areas using deep learning. AI IoT Smart City Appl. 223–233. (2022).

Demertzi, V., Demertzis, S. & Demertzis, K. An overview of cyber threats, attacks and countermeasures on the primary domains of smart cities. Applied Sciences, 13(2), p.790. (2023).

Kaddah, W., Gooya, E. S., Elbouz, M. & Alfalou, A. Securing Smart Cities Using Artificial Intelligence: Intrusion and Abnormal Behavior Detection Systempp. 120–125 (in: Pattern Recognition and Tracking XXXII, SPIE, 2021).

Reddy, D. K. et al. Deep neural network based anomaly detection in internet of things network traffic tracking for the applications of future smart cities. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun Technol. 32 (7), e4121 (2021).

Muthunagai, S. & Anitha, R. CTS-IIoT: Computation of time series data during index based de-duplication of Industrial IoT (IIoT) data in cloud environment, Wireless Pers. Commun., vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 433–453, Mar. (2023).

Elsaeidy, A. A., Jamalipour, A. & Munasinghe, K. S. A hybrid deep learning approach for replay and DDoS attack detection in a smart city. IEEE Access. 9, 154864–154875 (2021).

Nova, K. Security and resilience in sustainable smart cities through cyber threat intelligence. Int. J. Inform. Cybersecur. 6 (1), 21–42 (2022).

Sampathkumar, B. & Thanikachalam, R. A multiclass attack classification Framework for IoT using Hybrid Deep Learning Model. J. Cybersecur. Inform. Manage., (1), (2025). pp.151 – 51.

Khan, I. A. et al. Fed-inforce-fusion: A federated reinforcement-based fusion model for security and privacy protection of IoMT networks against cyber-attacks. Information Fusion, 101, p.102002. (2024).

Thantharate, P. & Anurag, T. December. CYBRIA-pioneering federated learning for privacy-aware cybersecurity with brilliance. In 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life using AI, Robotics and IoT (HONET) (pp. 56–61). IEEE. (2023).

Gwassi, O. A. H., Uçan, O. N. & Navarro, E. A. Cyber-XAI-Block: an end-to-end cyber threat detection & fl-based risk assessment framework for iot enabled smart organization using xai and blockchain technologies. Multimedia Tools and Applications, pp.1–42. (2024).

Alqurashi, F. A Hybrid Federated Learning Framework and Multi-Party Communication for Cyber-Security Analysis. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 14(7). (2023).

Park, J. H., Yotxay, S., Singh, S. K. & Park, J. H. PoAh-Enabled Federated Learning Architecture for DDoS Attack Detection in IoT Networks. Human-Centric Computing And Information Sciences, 14. (2024).

Djenouri, Y. & Belbachir, A. N. October. Empowering Urban Connectivity in Smart Cities using Federated Intrusion Detection. In 2023 IEEE 10th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) (pp. 1–9). IEEE. (2023).

Gaba, S., Budhiraja, I., Kumar, V., Garg, S. & Hassan, M. M. An innovative multi-agent approach for robust cyber-physical systems using vertical federated learning. Ad Hoc Networks, 163, p.103578. (2024).

Rawat, P. & Kumar, P. July. Blockchain based Federated Deep Learning Framework for Malware Attacks Detection in IoT Devices. In 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT) (pp. 1–10). IEEE. (2023).

Jain, R., Tihanyi, N. & Ferrag, M. A. Securing Tomorrow’s Smart Cities: Investigating Software Security in Internet of Vehicles and Deep Learning Technologies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.16410. (2024).

Kumar, R. et al. Blockchain-based authentication and explainable AI for securing consumer IoT applications. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. (2023).

Kumar, R., Kumar, P., Aloqaily, M. & Aljuhani, A. Deep-learning-based blockchain for secure zero-touch networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 61 (2), 96–102 (2022).

Kumar, P., Kumar, R., Aloqaily, M. & Islam, A. N. Explainable AI and blockchain for Metaverse: a security, and privacy perspective. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. (2023).

Satpathy, S., Swain, P. K., Mohanty, S. N. & Basa, S. S. July. Enhancing Security: Federated Learning against Man-In-The-Middle Threats with Gradient Boosting Machines and LSTM. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. (2024).

Myrzashova, R. et al. Safeguarding Patient Data-Sharing: Blockchain-Enabled Federated Learning in Medical Diagnostics. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing. (2024).

Prince, N. U. et al. A.B. and IEEE standards and Deep Learning techniques for securing internet of things (IoT) devices against Cyber attacks. J. Comput. Anal. Appl., 33(7). (2024).

Kollu, V. N., Janarthanan, V., Karupusamy, M. & Ramachandran, M. Cloud-based smart contract analysis in fintech using IoT-integrated federated learning in intrusion detection. Data, 8(5), p.83. (2023).

Zhang, X., Ren, Y., Xu, J. & Chi, C. August. Research and Application Framework for Trusted Circulation of Food Industry Data Based on Blockchain and Federated Learning. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain) (pp. 530–535). IEEE. (2024).

Tauseef, M., Kounte, M. R., Nalband, A. H. & Ahmed, M. R. Exploring the joint potential of Blockchain and AI for securing internet of things. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., 14(4). (2023).

Alamro, H. et al. Modelling of Bayesian-Based Optimized Transfer Learning Model for Cyber-Attack Detection in Internet of Things Assisted Resource Constrained Systems. IEEE Access. (2024).

Bashir, A. K., Rawat, D. B., Wu, J. & Imran, M. A. Guest Editorial Security, Reliability, and Safety in IoT-Enabled Maritime Transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24 (2), 2275–2281 (2023).

Hassan, S. M., Mohamad, M. M., Muchtar, F. B. & Dawoodi, F. B. Y. P. Enhancing MANET Security through Federated Learning and Multiobjective optimization: A Trust-aware Routing Framework. IEEE Access. (2024).

Bac, T. P., Ha, D. T., Tran, K. D. & Tran, K. P. Explainable Articial Intelligence for Cybersecurity in Smart Manufacturing. In Artificial Intelligence for Smart Manufacturing: Methods, Applications, and Challenges (199–223). Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2023).

Malik, R., Razzaq, H., Bhatt, C., Kaushik, K. & Khan, I. U. May. Advancing Healthcare IoT: Blockchain and Federated Learning Integration for Enhanced Security and Insights. In 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences and Engineering (IC3SE) (pp. 308–314). IEEE. (2024).

You, G., Hu, Y., Lian, C. & Yang, Z. Mixed-Strategy Harris Hawk Optimization Algorithm for UAV Path Planning and Engineering Applications. Applied Sciences, 14(22), p.10581 (2024).

Wang, H., Pan, H., Sun, J., Gu, X. & Palade, V. Fl-Mhae: Federated-Learning-Based Multiresolution Hybrid Auto-Encoder for Image Classification. Available at SSRN 4987074.

Eisa, M. G., Farahat, M. A., Abdelfattah, W. & Lotfy, M. E. Multiobjective Optimal Integration of Distributed Generators into Distribution Networks Incorporated with Plug-In Electric Vehicles Using Walrus Optimization Algorithm. Sustainability, 16(22), p.9948. (2024).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/munaalhawawreh/xiiotid-iiot-intrusion-dataset

Verma, P. et al. Zero-Day Guardian: a dual Model enabled Federated Learning Framework for handling zero-day attacks in 5G enabled IIoT. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. (2023).

Manickam, P. et al. Billiard based optimization with deep learning driven anomaly detection in internet of things assisted sustainable smart cities. Alexandria Eng. J. 83, 102–112 (2023).

Alrayes, F. S. et al. Improved Radial Movement Optimization With Fuzzy Neural Network Enabled Anomaly Detection for IoT Assisted Smart Cities. IEEE Access. (2023).

Acknowledgements

This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant no. (GPIP: 552-135-2024). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR at KAU for technical and financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahmoud Ragab: Conceptualization, methodology development, formal analysis, investigation, writing. Ehab Bahaudien Ashary: Methodology, investigation, validation. Bandar M. Alghamdi: Formal analysis, investigation, writing. Rania Aboalela: Formal analysis, investigation, review and editing. Naif Alsaadi: Validation, methodology, experiment, reviewand editing. Louai A. Maghrabi: Discussion, visualization, conceptualization, review and editing. Khalid H. Allehaibi: Conceptualization, methodology development, supervision, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The manuscript was written with contributions from all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This article contains no studies with human participants performed by authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ragab, M., Ashary, E.B., Alghamdi, B.M. et al. Advanced artificial intelligence with federated learning framework for privacy-preserving cyberthreat detection in IoT-assisted sustainable smart cities. Sci Rep 15, 4470 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88843-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88843-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Energy-efficient graph learning with blockchain–IoT integration for secure smart city energy management

Electrical Engineering (2026)

-

Identifying significant features in adversarial attack detection framework using federated learning empowered medical IoT network security

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Dynamic weight clustered federated learning for IoT DDoS attack detection

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Secure federated learning with metaheuristic optimized dimensionality reduction and multi-head attention for DDoS attack mitigation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

MedShieldFL-a privacy-preserving hybrid federated learning framework for intelligent healthcare systems

Scientific Reports (2025)