Abstract

The relationship between nutrient intake and osteoarthritis (OA) remains unclear. This study utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in a multi-cycle retrospective cohort study to explore the associations between the intake of six nutrients—carbohydrates, dietary fiber, protein, fat, folate, niacin and OA. This study performed a cross-sectional analysis using NHANES data from 1999 to 2018 to investigate the relationship between the intake of six nutrients and OA. Univariate and multivariate weighted logistic regression models, along with restricted cubic splines (RCS), were applied to assess the associations between nutrient intake and OA. A total of 32,484 participants were included in the study, of whom 1864 were diagnosed with OA, resulting in a prevalence rate of 5.74%. Multivariate weighted logistic regression consistently demonstrated that dietary fiber, folic acid, and nicotinic acid intake were negatively associated with the presence of OA, while protein intake exhibited a J-shaped relationship with OA, and carbohydrate or fat intake showed no significant association with OA. Compared with participants in the lowest quartile (Q1), those in the highest quartile (Q4) of dietary fiber, folic acid, and nicotinic acid intake had 27%, 28%, and 33% lower odds of having OA, respectively, after adjusting for potential confounding factors. RCS analysis revealed that dietary fiber and nicotinic acid intake had a nonlinear relationship with the presence of OA, folic acid intake had a linear relationship with OA, and protein intake followed a J-shaped curve with OA. These results suggest that higher intake of dietary fiber, folic acid, and nicotinic acid is associated with a reduced likelihood of OA, while protein intake follows a J-shaped curve, with moderate intake offering the greatest protection. These findings highlight the importance of balancing protein intake and optimizing the consumption of other nutrients for the prevention and management of OA. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease that primarily affects articular cartilage, subchondral bone, and synovial membranes1. It is characterized by joint pain, stiffness, and functional limitations, leading to reduced quality of life2. OA is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders globally, affecting millions of adults, particularly those over the age of 603. As the global population ages and obesity rates continue to rise, the incidence of OA is expected to gradually increase4. The number of people with OA is projected to nearly double by 2050, with an estimated 642 million people suffering from knee OA, which is also expected to increase by 74.9%3. The etiology of OA is multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, mechanical stress, and systemic inflammation5. A number of previous clinical studies have provided evidence that long-term use of ultra-processed foods can predispose individuals to a variety of chronic diseases6,7, and conversely, that some nutrient intake such as dietary fiber can reduce the inflammatory response to chronic inflammation8. Despite its prevalence and impact, effective preventive and therapeutic strategies for OA remain an ongoing challenge.

Diet is strongly associated with a variety of diseases and there have been many previous studies on diet and arthritis9,10. A longitudinal cohort study analyzing 2375 patients with OA through a dietary questionnaire found a significant association between specific dietary intake and reduced knee pain and improved quality of life for patients11.

A recent study has shown that high dietary fiber intake can alter intestinal flora and reduce systemic inflammatory responses and the extent of osteoarthritic lesions through the gut-bone axis12. Dr. Dai et al. conducted an 8-year prospective study and found that high folate intake plays an important role in knee protection in people with a high prevalence of osteoarthritis13. And a low-carb diet may reduce pain in people with knee OA14. In addition, obesity is one of the most common risk factors for arthritis, and dietary fiber may reduce the risk of arthritis by modulating the gut microbiota to achieve weight loss15. In addition, nutrient supplements play a role in the evolution of arthritis; for example, omega-3 supplementation improves morning stiffness and pain in joints. However, there are also conflicting studies on the effects of nutrient intake on patients with OA16,17. Thus, the relationship between dietary intake of carbohydrates, dietary fiber, protein, fat, folate, and niacin and the risk of OA remains poorly understood.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between carbohydrate, dietary fiber, protein, fat, folate, and niacin intake and the prevalence of OA among adults in the United States. The relationship between intake of these six nutrients and the presence of OA was explored by analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2018.

Materials and methods

Study population and design options

NHANES is a series of cross-sectional surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)18.The study is designed to collect data on the health, nutritional status, and behavior of noninstitutionalized adults and children in the U.S. NHANES is a cross-sectional survey study that collects data through personal interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory assessments on demographics, dietary habits. For more information about the survey and related research data, visit the official NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/). NHANES is widely used for the analysis of various diseases.

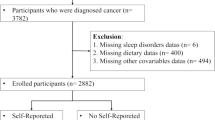

A total of 135,310 participants were enrolled in this study, and 10 NHANES data cycles (NHANES 1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, 2017–2018 cycles) in which the survey was completed. Of these, we excluded 67,842 participants who lacked OA, 8201 who lacked Carbohydrate/dietary fiber/protein/fat/folic acid/niacin, 153 for whom educational attainment was unavailable, 435 for whom marital status was unavailable, 4899 for whom poverty-to-income ratios were unavailable, 585 for whom body mass index (BMI) information was unavailable, 10 for whom diabetes mellitus (DM) history was not missing at this time, 10 for whom blood pressure information, 17 were unable to obtain smoking status, and 7191 were unable to obtain alcohol consumption status. Therefore, a total of 32,484 participants were ultimately included in this study. A flowchart detailing the study design can be seen in Fig. 1. The NHANES data were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent19.

Data collection

Exposure variable

We exposed data using carbohydrate、dietary fiber、protein、fat、folic acid and niacin intake, and this data source was collected primarily through two recall interviews. Participants were asked to recall what they had eaten in the past 24 h, with the first interview taking place at a mobile examination center (MEC) and the second follow-up visit taking place by telephone 3 to 10 days later20. Detailed information on all foods and beverages consumed by participants in the past 24 h was collected through the dietary recall method. To obtain detailed nutritional content of each diet, the researchers used the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Dietary Studies database (FNDDS)21. This database summarizes individual nutrient intakes, and dietary fiber intake was assessed according to the NHANES guidelines, with the final dietary fiber intake being the average of the two dietary interviews that were calculated.

Outcome variable

To assess whether a patient had OA, all participants were asked two questions about osteoarthritis. Firstly, if they answered “yes” to the question “Your doctor said you have arthritis” then they were considered to have arthritis (MCQ160A). However, there are many types of arthritis, and to further differentiate between the types of arthritis suffered, participants who answered “yes” to the first question were asked, “What type of arthritis” (MCQ195). Response options included “rheumatoid arthritis”, “osteoarthritis”, “psoriatic arthritis”, “other ”, “refused” and “don’t know”, and only those who answered “osteoarthritis” were considered to have OA.

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on prior literature and OA risk assessment and included age, gender, race, marital status, education level, body mass index (BMI), smoking and alcohol use, PIR, and baseline medical history status (hypertension and diabetes). We categorized race into four total: Mexican American, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other. Marital status was categorized into two categories, widowed/divorced/separated/never married or married/living with partner. The PIR is calculated as the ratio of household income to the federal poverty threshold, adjusted for family size and inflation. PIR is categorized as < 1.30, 1.31–3.49, or ≥ 3.50, corresponding to low income, middle income, and high income, respectively. Educational level was categorized using high school as the dividing line into less than a high school degree, a high school degree, and more than a high school degree (which includes college graduates or higher).BMI was measured offline by height and weight measurements at the first interview, and was categorized as normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2 ), heavy (25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2 ), and overweight (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 ) based on BMI. Smoking status was categorized into three types, never smoked/previously smoked/currently smoked. Alcohol consumption was defined as at least 12 drinks per year.

An average systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 140 mmHg and/or an average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 90 mmHg, as well as self-reported diagnosis of hypertension and antihypertensive drug use, were considered hypertension22,23. Participants were defined as diabetic if they had been diagnosed by a physician, had a hemoglobin A1c level above 6.5%, fasting blood glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random blood glucose level ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or were using diabetes medications or insulin24. Measurement details for these variables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analysis

To mitigate the effects associated with the intricate multi-stage sampling design employed by NHANES, we utilized the Day 1 dietary sample weight (WTDRD1) as delineated by the guidelines established by NHANES and performed weighted analyses to augment the precision of the data. Continuous variables are presented as weighted means with standard errors, and categorical variables are presented as counts with corresponding percentages. Subsequently, participants’ baseline features were assessed based on OA status using the Kruskal–Wallis and chi-square tests. To estimate the adjusted odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) for six nutrients quartiles, weighted logistic regression models were employed. The study constructed three weighted logistic regression models: Model 1 had no adjustments; Model 2 was adjusted for age, race, marital status, education level, and PIR; and Model 3 included further adjustments for BMI, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Additionally, the study applied weighted restricted cubic splines (RCS) to clarify the dose-response relationship between six nutrients and the presence of OA, adjusting for potential confounders. In order to investigate any potential differential connections between subgroups, we subsequently stratified the patients by age, race, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, hypertension, and diabetes and performed interaction analyses. Multicollinearity among the covariates was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). A VIF value below 10 was considered acceptable and indicative of no severe multicollinearity. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.1; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org), with statistical significance set at a two-sided P-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline population characteristics

A total of 32,484 eligible participants, aged between 20 and 85 years, were included in the final analysis. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, of these participants, 1864 self-reported having osteoarthritis and 30,620 reported normal joint function, resulting in a prevalence of OA of 5.74%. In the OA group, approximately 56.17% of the subjects were ≥ 60 years of age, 13.57% had less than high school education, 37.61% had low household income, 46.46% had a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/ m2, 63.36% had a history of smoking, and 75.43% had a background of alcohol consumption. In addition, in the OA group, 23.18% of the subjects were diagnosed with diabetes and 66.95% with hypertension. Statistically significant differences were found between the two groups of subjects in terms of age, race, gender, PIR, education, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, and prevalence of hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (P < 0.05). Participants with OA had lower median intakes of carbohydrates (215 vs. 243 g), dietary fiber (19 vs. 22 g), protein (66 vs. 76 g), fat (68 vs. 75 g), folic acid (311 vs. 349 µg), and niacin (19 vs. 22 mg) compared to non-OA participants. Additionally, the proportion of OA cases was highest in the lowest intake quartile (Q1) for all six nutrients, such as carbohydrates (33.74%) and dietary fiber (35.19%). The VIF analysis revealed that all covariates had VIF values between 1 and 3, indicating no significant multicollinearity. Detailed results of the VIF analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Association between nutrients intake and OA

We used a weighted multivariate logistic regression analysis to investigate the association between different nutrient intake levels and the presence of OA across various models. The results, as shown in Table 1, demonstrated negative associations between the levels of dietary fiber, folate, and niacin intake and the presence of OA. However, a J-shaped relationship was observed for protein intake. Both univariate and multivariate weighted logistic regression models consistently indicated inverse associations between dietary fiber, folate, niacin, and the odds of having OA. In addition, we transformed dietary fiber, protein, folate, and niacin into categorical variables expressed in quartiles to enhance the rigor of the analysis. In Model 3, after adjusting for all possible covariates, participants in the highest quartile (Q4) of dietary fiber, folate, and niacin intake had 27%, 28%, and 33% lower odds of having OA compared to participants in the lowest quartile (Q1), respectively (Table 1). For protein intake, participants in the third quartile (Q3) had the lowest odds of having OA, whereas those in the highest quartile (Q4) exhibited a slightly elevated odds compared to Q3, consistent with a J-shaped relationship.

Dose-response curve analysis using RCS confirmed the J-shaped relationship between protein intake and the presence of OA, as well as nonlinear relationships for dietary fiber and niacin intake, with the presence of OA decreasing within certain ranges of intake (Fig. 2). In addition, a linear inverse relationship was observed between folate intake and the presence of OA, which decreased as folate intake increased (Fig. 2). No significant associations were found between carbohydrate or fat intake and OA.

Subgroup analysis

We performed stratified analyses to assess whether the associations between the six nutrients and OA differed across subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our findings showed no significant differences in the associations between carbohydrates, dietary fiber, protein, and fat and the presence of OA in the subgroup analyses (interaction P > 0.05). Interactions were found in the subgroup analyses of folate and niacin with OA, with interactions between hypertension and folate, and race and niacin (P < 0.05 for interaction). Specifically, after adjusting for covariates, the effect of folic acid on reducing the odds of having OA was more pronounced in those without hypertension. After adjusting for covariates, the effect of niacin on reducing the odds of having OA was more pronounced in the Mexican American and Non-Hispanic White races.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between intake of six key nutrients (carbohydrates, dietary fiber, protein, fat, folate, and niacin) and the presence of OA using cross-sectional data from NHANES (1999–2018). Results showed significant negative associations between the intake of dietary fiber, folate, and niacin and the odds of having OA, while protein intake exhibited a J-shaped relationship with the odds of having OA, indicating that moderate intake was associated with the lowest odds. No significant associations were found for carbohydrate or fat intake. These findings provide important insights into the potential role of diet in the prevention and management of OA.

Different dietary patterns are closely related to human health. Nutrient deficiencies often lead to disease. Previous studies have confirmed that dietary fiber can positively regulate intestinal flora and metabolically form beneficial products such as short-chain fatty acids, which have significant advantages in reducing the risk of gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome25,26. In addition, dietary fiber intake plays a positive role in cardiovascular disease27, liver disease28, and dyslipidemia29. Protein intake is important with muscle, bone and joint cartilage. Inadequate intake of folic acid, or even deficiency, is associated with a variety of diseases including gynecological, cancer, and musculoskeletal disorders30. In addition, niacin has been found to be associated with pellagra31, glaucoma retinal function32, and a variety of neurological disorders33. Thus, the importance of maintaining levels of various nutrients in the body cannot be overstated.

OA belongs to the list of culprits that affect the health of most people’s lives and its prevalence is increasing every year. In studying the pathogenesis of OA, we have found that aging, inflammation and weight gain are very important influencing factors. Previous studies have found that dietary fiber, folic acid, and niacin have been found to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-modulating effects34, and that proteins have also been found to have a protective effect on articular cartilage, which in turn improves OA-related symptoms16,35.

Furthermore, with the concept of the gut-skeletal axis, studies have shown that aging and obesity in the body have a great impact on the composition of the gut microbiota and that gut flora modulates joint inflammation12. Dietary fiber is an easily overlooked nutrient, but most studies have shown that it has a positive impact on the health of the organism. Studies have confirmed that consuming a certain amount of dietary fiber can help slow down aging or reduce the risk of obesity36,37. However, an analysis of ten years of data on dietary fiber intake among adults in the United States showed that bread and cereals were their main sources of dietary fiber, with low levels of both overall intake38. A large-sample prospective cohort study through 4,796 participants found that higher total dietary fiber intake was associated with a lower risk of osteoarthritis39. Furthermore, niacin reduces cholesterol levels in cartilage, which in turn eases the progression of OA. A recent study found that niacin, an ancient cholesterol-lowering drug, can mitigate the progression of osteoarthritis by its ability to enhance cholesterol efflux from chondrocytes40. Another study found enhanced cholesterol hydroxylase uptake and increased production of oxysterol metabolites in OA chondrocytes, whereas retinoic acid-associated orphan receptor α (RORα) was found to mediate osteoarthritis progression by altering cholesterol metabolism through animal experiments in mice41.

From a biological perspective, the protective role of folic acid against OA may be attributed to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Folic acid plays a pivotal role in homocysteine metabolism, reducing homocysteine levels that, if elevated, are known to promote oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which contribute to cartilage degradation and OA progression34. Additionally, folic acid has been shown to modulate immune responses, potentially mitigating the inflammatory pathways implicated in OA42. However, the molecular biological mechanisms of the protective effects of different nutrients against OA still need to be investigated more thoroughly in more animal experiments. Moreover, whether diet-specific intake has a better protective effect against OA and what the optimal dose is still needs to be verified in large-scale clinical trials.

More previous studies on the relationship between diet and arthritis exist, and a number have found that specific dietary intake slows the symptoms of arthritis19,20,21. However, there is a lack of analysis of the elements of the diet that work to more accurately access beneficial foods. Previous studies have focused on how a particular type of dietary intake affects OA disease43,44,45, but none of these studies have been able to provide patients and healthcare providers with the starting elements. Instead, NHANES calculates intake of specific nutrients by counting large samples and analyzing specific food components, including nutritional supplements. Our study provides insight into the health benefits of different nutrients and helps raise awareness of the need to consume dietary fiber, protein, folate and niacin. This provides ideas for clinicians in the treatment of OA, as well as prevention for patients with joint pain and OA. More studies between different nutrients and OA should be added in the future, which will also reduce the burden of OA on national health insurance.

The strength of this study is that it focuses on the relationship between intake of different nutrients and OA and is supported by a large sample. Then again, the study has some limitations. First, the diagnosis of OA we used was self-reported from the participants, and although this method allows for rapid data collection from a large population, there is a risk of lack of accuracy. And, because the study was retrospective in design, it was not possible to confirm a causal relationship between exposure and outcome. Second, although we adjusted for common confounders affecting OA, there may still be residual confounders, which could potentially influence the relationship between nutrients and OA. Third, the population we studied was the US population, and further, larger sample studies are needed to determine whether the benefits of different nutrient intakes can be generalized to other populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study based on NHANES (1999–2018) found negative associations between dietary fiber, folate, and niacin intake and OA in the U.S. population after adjusting for potential confounders. Protein intake showed a J-shaped relationship with OA, with the lowest quartile (Q1) associated with a significantly higher risk, while no significant associations were observed in higher quartiles. These findings suggest that optimizing nutrient intake, particularly increasing dietary fiber, folate, and niacin, and avoiding inadequate protein intake, may help reduce the odds of having OA. Further research and randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm these results and determine effective dietary strategies for OA prevention and management.

Data availability

All datasets used during the current study can be found on the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

References

Jang, S., Lee, K. & Ju, J. H. Recent updates of diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment on osteoarthritis of the knee. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052619 (2021).

Hawker, G. A. & King, L. K. The burden of osteoarthritis in older adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 38(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.005 (2022).

Global and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 5(9), e508–e522. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(23)00163-7 (2023).

Hu, Y., Chen, X., Wang, S., Jing, Y. & Su, J. Subchondral bone microenvironment in osteoarthritis and pain. Bone Res. 9(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-021-00147-z (2021).

Guan, S. Y. et al. Global burden and risk factors of musculoskeletal disorders among adolescents and young adults in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Autoimmun. Rev. 22(8), 103361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103361 (2023).

Srour, B. et al. Ultra-processed foods and human health: from epidemiological evidence to mechanistic insights. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 (12), 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(22)00169-8 (2022). eng. Epub 2022/08/12.

Elliott, P. S., Kharaty, S. S. & Phillips, C. M. Plant-based diets and lipid, lipoprotein, and inflammatory biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: A review of observational and interventional studies. Nutrients. 14(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245371 (2022).

Sánchez-Rosales, A. I., Guadarrama-López, A. L., Gaona-Valle, L. S., Martínez-Carrillo, B. E. & Valdés-Ramos, R. The effect of dietary patterns on inflammatory biomarkers in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 14(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214577 (2022).

Xie, Z. & Qin, Y. Is diet related to osteoarthritis? A univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization study that investigates 45 dietary habits and osteoarthritis. Front. Nutr. 10, 1278079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1278079 (2023).

Morales-Ivorra, I., Romera-Baures, M., Roman-Viñas, B. & Serra-Majem, L. Osteoarthritis and the mediterranean diet: a systematic review. Nutrients. 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081030 (2018).

Zheng, Z., Luo, H. & Xue, Q. Association between niacin intake and knee osteoarthritis pain and function: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Rheumatol. 43 (2), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06860-w (2024). eng. Epub 2024/01/05.

Wu, Y. et al. Dietary fiber may benefit chondrocyte activity maintenance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1401963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1401963 (2024).

Dai, Z., Lu, N., Niu, J., Felson, D. T. & Zhang, Y. Dietary fiber intake in relation to knee pain trajectory. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 69 (9), 1331–1339. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23158 (2017).

Strath, L. J. et al. The effect of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on pain in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 21 (1), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz022 (2020).

Tian, S., Chu, Q., Ma, S., Ma, H. & Song, H. Dietary fiber and its potential role in obesity: a focus on modulating the gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 71(41), 14853–14869. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.3c03923 (2023).

Mathieu, S. et al. A meta-analysis of the impact of nutritional supplementation on osteoarthritis symptoms. Nutrients. 14(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081607 (2022).

Zhao, Z. X. et al. Does vitamin D improve symptomatic and structural outcomes in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 33 (9), 2393–2403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01778-8 (2021).

Bailey, R. L., Pac, S. G., Fulgoni, V. L. 3, Reidy, K. C. & Catalano, P. M. Estimation of total usual dietary intakes of pregnant women in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2(6), e195967. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5967 (2019).

Fang Zhang, F. et al. Trends and disparities in diet quality among US adults by supplemental nutrition assistance program participation status. JAMA Netw. Open. 1(2), e180237. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0237 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Associations of diet quality and heavy metals with obesity in adults: a cross-sectional study from national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES). Nutrients. 14(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194038 (2022).

Pan, J., Hu, Y., Pang, N. & Yang, L. Association between dietary niacin intake and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Nutrients. 15(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15194128 (2023).

Flack, J. M. & Adekola, B. Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 30 (3), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.05.003 (2020). Epub 20190515.

Reboussin, D. M. et al. ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines. Circulation 138 (17), e595–e616. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000601 (2018). Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 30354656.

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 45(Suppl 1), S17–S38. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S002 (2022).

Guan, Z. W., Yu, E. Z. & Feng, Q. Soluble dietary fiber, one of the most important nutrients for the gut microbiota. Molecules. 26(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226802 (2021).

Gill, S. K., Rossi, M., Bajka, B. & Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18 (2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-00375-4 (2021).

Shivakoti, R. et al. Intake and sources of dietary fiber, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease in older US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 5(3), e225012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5012 (2022).

Shen, H. et al. Dietary fiber alleviates alcoholic liver injury via Bacteroides acidifaciens and subsequent ammonia detoxification. Cell. Host Microbe. 32 (8), 1331–1346e. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2024.06.008 (2024). 6. eng. Epub 2024/07/04.

Lu, K. et al. Effect of viscous soluble dietary fiber on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized clinical trials. Front. Nutr. 10, 1253312. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1253312 (2023).

Hwang, S. Y., Sung, B. & Kim, N. D. Roles of folate in skeletal muscle cell development and functions. Arch. Pharm. Res. 42 (4), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-018-1100-9 (2019).

Prabhu, D., Dawe, R. S. & Mponda, K. Pellagra a review exploring causes and mechanisms, including isoniazid-induced pellagra. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 37 (2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpp.12659 (2021).

Hui, F. et al. Improvement in inner retinal function in glaucoma with nicotinamide (vitamin B3) supplementation: a crossover randomized clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 48 (7), 903–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.13818 (2020).

Wuerch, E., Urgoiti, G. R. & Yong, V. W. The promise of niacin in neurology. Neurotherapeutics 20 (4), 1037–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-023-01376-2 (2023).

Shea, B. et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013(5), Cd000951. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000951.pub2 (2013).

Nguyen, H. D., Oh, H. & Kim, M. S. An increased intake of nutrients, fruits, and green vegetables was negatively related to the risk of arthritis and osteoarthritis development in the aging population. Nutr. Res. 99, 51–65 (2022).

Matt, S. M. et al. Butyrate and dietary soluble fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front. Immunol. 9, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832 (2018).

Delzenne, N. M. et al. Nutritional interest of dietary fiber and prebiotics in obesity: lessons from the MyNewGut consortium. Clin. Nutr. 39 (2), 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.03.002 (2020).

McGill, C. R., Fulgoni, V. L. 3 & Devareddy, L. Ten-year trends in fiber and whole grain intakes and food sources for the United States population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2010. Nutrients. 7(2), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7021119 (2015).

Dai, Z., Niu, J., Zhang, Y., Jacques, P. & Felson, D. T. Dietary intake of fibre and risk of knee osteoarthritis in two US prospective cohorts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 (8), 1411–1419. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210810 (2017). eng. Epub 2017/05/26.

Lee, G. et al. Enhancing intracellular cholesterol efflux in chondrocytes alleviates osteoarthritis progression. Arthritis Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42984 (2024).

Choi, W. S. et al. The CH25H-CYP7B1-RORα axis of cholesterol metabolism regulates osteoarthritis. Nature 566 (7743), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0920-1 (2019).

de Candia, P. & Matarese, G. The folate way to T cell fate. Immunity. 55(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.12.009 (2022).

Wei, Y. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption, genetic susceptibility, and the risk of hip/knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Nutr. 43 (6), 1363–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.04.030 (2024).

Veronese, N., Ragusa, F. S., Dominguez, L. J., Cusumano, C. & Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet and osteoarthritis: an update. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36(1), 231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02883-8 (2024).

Diao, Z. et al. Causal relationship between modifiable risk factors and knee osteoarthritis: a mendelian randomization study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 11, 1405188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1405188 (2024).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Study design, data collection and statistical analysis, X.F.L., X.M.D., R.L., Writing-original draft, X.F.L., X.M.D., R.L., S.S.L.; Writing-review and editing, X.F.L., X.M.D., S.S.L., Z.H.Z., X.C.D., Y.L.L., J.L., Y.L.; Supervision: J.L., Y.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and informed Consent Statement

NHANES is a publicly available, free database that has been approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board and agreed to by all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, X., Deng, X., Lai, R. et al. Associations between nutrient intake and osteoarthritis based on NHANES 1999 to 2018 cross sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 4445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88847-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88847-y