Abstract

With the development of mobile internet and artificial intelligence, the core of current surveying and mapping science and technology is no longer confined solely to outdoor applications. High-precision indoor positioning technology is now one of the core technologies in the era of artificial intelligence. An angle measurement and positioning system based on wireless signal array antennas can achieve high accuracy in indoor unblocked conditions. However, indoor environment is unpredictable, and the user's behavior is also random. Inevitably, some signal reflection and other factors will affect the positioning accuracy. Considering all the aforementioned, this study analyzes the principles and characteristics of a Bluetooth signal based array antenna angle measurement and positioning system. In addition, aiming at the multi-phase problem caused by antenna switching, the frequency estimation method based on FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) is studied in this paper, achieving high-precision angle measurement and positioning. Aiming at the problem that the system positioning error increase in the complex and variable indoor environment, a fusion positioning method of Bluetooth array/PDR (Pedestrian Dead Reckoning) based on the SVD-EKF (Singular Value Decomposition–Extended Kalman Filter) is proposed. This study introduces a few improvements to the EKF (Extended Kalman Filter). First, the predicted state covariance matrix is decomposed by singular value decomposition, which improves the robustness of the EKF. Second, a Bluetooth array self-evaluation factor is introduced and combined with the Huber function to construct an adaptive factor, thus further enhancing filtering accuracy and environmental adaptability. Through static and dynamic data collected in indoor environment, the feasibility of the algorithm is verified. The results of static and dynamic experimental results show that the array angle measurement and positioning system can achieve high accuracy, the near point positioning maximum error is 0.3m and the far point positioning accuracy is 0.6m. The dynamic test results in the room show that after SVD-EKF algorithm optimization, the positioning error is reduced by 0.05m, which is equivalent to the EKF algorithm. However, in corridor areas, the improvement of accuracy of SVD-EKF algorithm is better than EKF, achieving an improvement of 0.373 m and a smoother positioning result compared to the traditional EKF algorithm. This study provides a new practical technology with a high precision and easy deployment for indoor positioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, smart terminals such as mobile phones and tablet computers have gradually become an indispensable tool in public life. At the same time, people's demand for service performance of handheld positioning is getting higher and higher1,2,3. The GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) is the primary source of high-precision location information when the user is outdoors4. Its accuracy can meet people's daily needs, and this system has been widely used in various industries, such as transportation, agriculture, and commerce5. The convenience brought by the acquisition of high-precision location information in outdoor conditions is highly appreciated6,7. However, numerous studies have shown that most people's activities occur indoors8,9, and large-scale shopping malls, airports, stations, and other crowded indoor places require efficient crowd monitoring and dynamic analysis methods10,11. For instance, in mines, high-rise buildings, and other scenarios with special work types, it is necessary to locate internal personnel in real-time during emergencies. Similarly, medical care institutions need to locate care recipients in real-time to provide timely and proper medical care services. In recent years, numerous scholars have tried to use basic physical field characteristics, such as sound12, light13,14, electricity15,16,17,18, magnetism19, and force20, to determine parameters related to indoor locations. However, an indoor environment is unpredictable, and the existing indoor positioning technologies have not yet been mature and highly accurate21. Currently, there has been no indoor positioning technology that can provide high precision, low cost, and easy deployment simultaneously22.

Exploring new positioning sources and developing high-precision, high-availability positioning technologies is the current trend in indoor positioning technology. Currently, indoor positioning sources can be categorized into radio frequency signals, motion sensors, visual signals, audio signals, light source signals, environmental feature signals, and more. Due to various limitations such as indoor spatial environments, signal types, and sensor performance, current methods relying on a single signal source, a single sensor source, integrated navigation, and fusion positioning still suffer from inadequacies in positioning accuracy, stability, reliability, and speed. These limitations make it challenging to meet the demands for high-precision indoor positioning. Compared to single positioning technologies, a method that uses wireless high-precision real-time positioning to determine locations as control calibration points, combined with short-term high-precision fusion positioning using micro-inertial navigation, is more suited for indoor positioning scenarios.

In our approach, we propose a single-base station positioning method based on Bluetooth signals. This method employs a circular array antenna for direction finding, combined with the deployment height of the base station to achieve positioning. A single base station is capable of performing two-dimensional positioning. However, the positioning coverage and accuracy of a Bluetooth array are highly related to the deployment height of base stations. Namely, in many low-lying scenarios, although the positioning accuracy is high, the coverage area is small. In such situations, to achieve full coverage, it is necessary to deploy additional base stations, which substantially increases the positioning cost.

To address the aforementioned issues, we propose a Bluetooth array–PDR fusion positioning method based on the SVD-EKF (Singular Value Decomposition Extended Kalman Filter), which combines high precision of Bluetooth arrays and wide coverage of the PDR. By introducing the concept of SVD, we perform SVD on the covariance matrix to ensure its non-negative definiteness after multiple calculations. Additionally, we incorporate a circular array polarization factor for adaptive robustness, constructing test information based on the innovation vector and its covariance matrix to address the decline in filter accuracy caused by disrupted optimal conditions. The improved Sage-Husa filter is utilized to continuously estimate and correct the covariance matrix of system noise in real-time, thereby reducing the state estimation error.

Our contributions to the field of indoor localization systems include two aspects. (1) A single-base station positioning method based on Bluetooth signals. This method overcomes the limitations of ranging positioning systems that require precise timing and multiple base stations for positioning. It achieves precise positioning with angle measurement from a single base station and features low cost and easy deployment. (2) A Bluetooth array/PDR fusion positioning method based on the SVD-EKF (Singular Value Decomposition Extended Kalman Filter). This method addresses the issue of limited coverage in low-lying environments by combining the high precision of Bluetooth arrays with the wide coverage of PDR. We propose this method as an alternative to traditional systems that may struggle in such environments. Our aim is provide a novel and practical technology for indoor positioning that is low-cost, high-precision, and easy to deploy. Furthermore, we strive to offer new insights into the improvement of Kalman filtering techniques, particularly in the context of indoor localization systems.

The structure of this paper is divided into five sections: introduction, literature review, methods, evaluation, and conclusions. (1) We introduce the subject and our approach to the issue. (2) We review the current literature on the common approaches for indoor tracking and localization. (3) We propose a dual-channel dual-polarized Bluetooth array positioning method. We analyze the errors generated during the positioning process and subsequently propose a fusion positioning method based on the EKF. Additionally, we make improvements to the EKF. (4) We provide a detailed introduction to the testing environment and methodology. Both static and dynamic experimental validations of the algorithm are conducted in indoor environments. (5) Our paper concludes with the conclusions section.

Literature review

The literature reveals that, current categories of indoor positioning sources can be divided into radio frequency signals, motion sensors, visual signals, audio signals, light source signals, and environmental feature signals. Bluetooth has been one of the most common short-distance wireless communication technology specifications in people’s daily lives23,24. It was first proposed by Ericsson in 1994 and has matured compared to the other technologies after more than 20 years of development25,26. The BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) in the protocol indicates the requirements of indoor positioning caused by its low energy consumption27,28,29. Early positioning methods based on BLE typically relied on fingerprint matching for localization. This method required regular updates to the fingerprint database and had relatively low positioning accuracy, gradually fading out of the mainstream positioning landscape.

AOA (Angle of Arrival) positioning is a high-precision positioning method. Compared to a multi-base station positioning method that measures time and distance, a high-precision angle measurement positioning technology can be used for single base station positioning. This method can reduce costs and avoid problems such as time synchronization of base stations and joint calculation of different base stations30. To eliminate frequency synchronization errors, Zhen et al. proposed a dual-channel antenna array and combined them with a phase comparison angle measurement method for comparing antennas31,32. Although this method eliminates frequency errors, it also reduces the signal resolution during the phase comparison process, thereby decreasing the positioning accuracy.

Multi-source fusion positioning is currently one of the main methods for addressing the problems of high cost, low positioning accuracy, and poor generalization capabilities in indoor positioning. Particularly, the combination of inertial sensors with high-precision positioning technologies forms a solution that can ensure low cost, high precision, and wide coverage33,34. Inertial sensors are the core positioning devices for multi-source fusion technology. For smartphones, these sensors are ubiquitous, available, low-cost, and low-power consuming and have the highest data output frequency, which provides them an obvious advantage in multi-source fusion solutions35,36,37. Therefore, the PDR (Pedestrian Dead Reckoning) has been widely adopted in pedestrian navigation and positioning38. The three key issues in PDR are step detection, step length estimation, and heading estimation. Poulose et al.39 proposed a pitch-based step detection algorithm that reduces the error in step detection. Nonetheless, due to the complexity of a user’s phone-holding postures and differences in a phone’s inertial sensor hardware, conventional PDR has many shortcomings in terms of positioning accuracy, phone generalization ability, and support for multiple holding postures. Therefore, the selection of the fusion method can significantly affect the fusion result40,41.

To realize an accurate system state estimation using a classical kalman filter, the prerequisite is that the dynamic model of the system is accurate and that the noise is an uncorrelated white noise. Also, to ensure system stability, appropriate initial value and variance matrix must be selected. However, in a complex indoor environment, it is obviously difficult to guarantee. Aiming to solve this problem, many adaptive filtering algorithms based on the estimation algorithm of statistical characteristics of time-varying noise have been proposed. When the covariance matrix of the system noise and the covariance matrix of the measurement noise are uncertain, the adaptive filtering uses the information on the observed data to estimate and correct the statistical characteristics of the noise continuously so as to reduce the state estimation error. Among and algorithms for uncertainty, the Sage–Husa algorithm is most representative. The EKF (Extended Kalman Filter) is simple to calculate and easy to implement, and for moderate function nonlinearity, the EKF can achieve excellent filtering effects42,43.

Methods

Array antenna angle of arrival positioning algorithm

Positioning principle

A Bluetooth array angle measurement is to measure the azimuth and pitch angle of a signal received by an array antenna, combined with the layout height of the base station to achieve two-dimensional positioning.

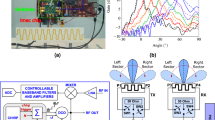

Figure 1 shows the array antenna model. The array has 13 antennas, including 12 around and 1 in the middle. The surrounding antennas are 6 pairs of orthogonal antennas, which switch data acquisition in turn during data acquisition. The antenna in the middle collects data separately. Therefore, the middle antenna has the largest number of data acquisition, which is suitable for frequency estimation. The position observation diagram are presented in Fig. 2.

Suppose \(s(t)\) is the waveform of the data and its wavelength is \(\lambda_{{0}}\). The azimuth angle and pitch angle are \(\varphi\) and \(\theta\) respectively. The frequency of signal source is set to \(f_{0}\). The switching time between antennas is \(T\). The signal model that can obtain the frame data is:

where \(B\) indicates the transmitting power of the signal; \(p_{n} (\theta ,\,\varphi ,\,\gamma ,\,\eta )\) indicates the polarization type; \(\gamma\) and \(\eta\) are information related to polarization; \(\tau_{n} (\theta ,\,\phi )\) represents the signal’s time delay to the nth array element; \(f_{d}\) is the Doppler frequency.

The matrix is expressed in column vector as:

where \({\mathbf{p}}(\theta ,\,\varphi ,\,\gamma ,\,\eta ){ \,= \,}{\mathbf{P}}(\theta ,\varphi ){\mathbf{w}}(\gamma ,\eta )\), \({\mathbf{P}}(\theta ,\varphi ){ \,= \,}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{p}}_{1}^{T} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ {{\mathbf{p}}_{2}^{T} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ \vdots \\ {{\mathbf{p}}_{2N}^{T} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \({\mathbf{w}}(\gamma ,\eta ){ \,= \,}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\cos \gamma } \\ {\sin \gamma e^{i\eta } } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \({\mathbf{a}}_{s} {(}\theta {,}\phi {) = }\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {e^{{ - i2\pi f_{0} \tau_{1} (\theta {,}\phi )}} e^{{i2\pi (f_{d} + f_{\Delta } )[(n - 1)T + t - \tau_{1} (\theta ,\,\phi )]}} } \\ {e^{{ - i2\pi f_{0} \tau_{2} (\theta {,}\phi )}} e^{{i2\pi (f_{d} + f_{\Delta } )[(n - 1)T + t - \tau_{2} (\theta ,\,\phi )]}} } \\ \vdots \\ {e^{{ - i2\pi f_{2N} \tau_{1} (\theta {,}\phi )}} e^{{i2\pi (f_{d} + f_{\Delta } )[(n - 1)T + t - \tau_{2N} (\theta ,\,\phi )]}} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), and \(e\) is the Hardmard product.

Considering the noise of the base station receiver hardware itself, the signal vector is as follows::

where \({\mathbf{a}}(\theta ,\,\phi ,\,\gamma ,\,\eta ){ \,= \,}{\mathbf{p}}(\theta ,\,\phi ,\,\gamma ,\,\eta )e{\mathbf{a}}(\theta ,\,\phi )\), and \({\mathbf{n}}_{i}\) is receiver noise vector, and its covariance matrix \({\varvec{R}}_{n}\).

The indoor environment is very complex, and the movement of users is also random. Therefore, during the positioning process, the base station will receive multi-path echoes caused by many obstacles. Assume that the number of signals collected is \(P\). Taking these effects into account, formula (4) can be written as:

where \( {\mathbf{A}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{a}}(\theta _{1} ,\phi _{1} ,\gamma _{1} ,\eta _{1} )} & {{\mathbf{a}}(\theta _{2} ,\phi _{2} ,\gamma _{2} ,\eta _{2} )} & {L\quad {\mathbf{a}}(\theta _{P} ,\phi _{P} ,\gamma _{P} ,\eta _{P} )} \\ \end{array} } \right] \) represents the array manifold matrix of darkroom acquisition; \({\mathbf{s}}_{i}\) is the signal vector, the formula is as follows:

Multipath signals will cause large errors, so in the indoor environment, it is necessary to judge whether the identification signal is a multipath signal, and the super-resolution Angle estimation method is used in this case. MUSIC (Multiple Signal classification) spectrum estimation algorithm is a common super-resolution angle estimation method. Compared with other methods, this method is less complex and more practical. Therefore, this algorithm is adopted in this study.

After obtaining the azimuth angle and pitch angle, the source coordinates can be obtained by combining the positioning observation diagram as follows:

where, \(h\) is base station layout height.

The precondition for super-resolution angle estimation is accurately defined array manifold. The array manifold of a polarizing sensitive circular array is related to both the signal transmission angle and the polarization type. Due to the processing errors in array antennas and significant coupling in circular arrays, it is challenging to realize super-resolution applications by directly using theoretically calculated array manifolds. Therefore, this study adopts the method of darkroom measurements to obtain the array manifold of an array antenna when the incident signal is horizontally and vertically polarized. Since the grid points in the darkroom measurement are relatively sparse, significant errors could arise in the angle measurement. Thus, to improve the angle estimation accuracy, the grid points need to be denser, which indicates that interpolation of the measured data is required to obtain an array manifold matrix of the Bluetooth array with densified grid points. The amplitude images of the vertically and horizontally polarized array manifolds after interpolation are presented in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively.

Error analysis

The frequency synchronization error can result in a deviation between \(\overline{{f_{0} }}\) and \(f_{0}\), and the difference between them is \(f_{\Delta } { \,= \,}f_{0} - \overline{{f_{0} }}\). Figure 5 shows the amplitude diagram and phase diagram. Since the amplitude can reflect the signal strength, and the single-channel rotational mining does not affect the signal strength, the mining neither affects the amplitude. However, the existence of a redundant phase can be clearly seen from the phase diagram, and phase instability will reduce positioning accuracy. Therefore, to achieve high precision positioning, the frequency deviation must be accurately estimated.

The height of base station layout can generally meet the far field condition. So Eqs. (1) and (2) can be written as:

By FFT for \(N\) points of channel 2, the following spectrum can be obtained:

where \(k\) is the spectrum line.

Next, calculate the maximum value of the spectrum. After the maximum value is obtained, assume that the corresponding spectral line is \(k_{1}\). According to the principle of the maximum likelihood estimation, the following formula can be obtained:

According to Eq. (11), the data length of FFT determines the accuracy of frequency estimation. The data length is positively correlated with the accuracy. In this system, the length of FFT is the number of data points collected by channel 2. These points are the sum of the points collected by the other 12 antennas. As a result, highly accurate frequency estimates can be obtained.

The frequency deviation is estimated by FFT, and the data amplitude and phase diagram after frequency deviation compensation is shown in Fig. 6. By comparing the phase diagram in Fig. 5, it can be observed that the excess phase caused by antenna rotation mining is eliminated.

In this system, the positioning error caused by the frequency offset can be eliminated by frequency estimation methods. However, the interior is mostly NLOS (Non Line of Sight) environment. In this case, In this case, the positioning error of the system increases sharply. Therefore, it is difficult for a single system to achieve high-precision positioning when the signal is affected; also, the coverage range of a Bluetooth array is limited in low environments. Nevertheless, inertial navigation can provide high-precision relative positions in a short period. Therefore, using low-cost inertial navigation can reduce the system's positioning errors in NLOS environments and can extend the system's positioning range; thus, it is a primary solution to address the aforementioned problems.

Bluetooth array–PDR fusion positioning method

Bluetooth array/PDR fusion positioning method based on EKF

As mentioned before, for a function with moderate nonlinearity, the EKF can achieve a very good filtering effect. Considering that the algorithm introduced in this paper is primarily intended for human activity scenarios where state changes are relatively slow, the EKF is selected for fusion positioning. During the system modeling process, it is assumed that the motion of a pedestrian in a two-dimensional space represents uniform linear motion. Given the known parameters, such as the initial position, the angle with the north reference axis, and motion direction, based on the basic principle of the PDR, the pedestrian's new coordinates at the next time point can be calculated by:

A pedestrian's motion trajectory can be regarded as a trajectory composed of numerous discrete step points. If the length and time interval of a step are known, the step can be considered uniform motion. Assume that a pedestrian's position coordinates at a time (\(k - 1\)) are \((x_{k - 1} ,y_{k - 1} )\), the step length of the \(k\)th step is \(l\), and the motion time is \(\Delta t_{k}\); the corresponding schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 7.

Therefore, the speed of a pedestrian traveling to the \(k\)th step can be calculated as follows:

The northward and eastward velocities at the \(k\)th step can be calculated as follows:

Therefore, the user's position after completing the \(k\)th step can be expressed by:

In the process of uniform motion, a change in a pedestrian’s velocity between two consecutive steps is not significant, so it can be assumed that the equivalent velocities of the preceding and subsequent steps are the same. Therefore, the system's state vector can be represented by \({\mathbf{X}}_{k} = \left[ {x_{k} ,y_{k} ,v_{n,k} ,v_{e,k} } \right]^{T}\). Then, based on Eq. (16), the system's state equation can be derived by:

The state transition matrix \({{\varvec{\Phi}}}\) of a pedestrian from time (\(k - 1\)) to the next moment is defined by:

where \({\mathbf{W}}_{k - 1} = \left[ {a_{n,k} ,a_{e,k} } \right]^{T}\) represents the acceleration noise of a pedestrian in the northward and eastward directions from time (\(k - 1\)) to the next moment, which represents the system noise; in this study, \({\mathbf{W}}_{k - 1} = \left[ {0.1,0.1} \right]^{T}\).

The coefficient matrix of the system noise is \({{\varvec{\Gamma}}}\), and it can be defined by:

The northward and eastward coordinates of a pedestrian at a time \(k\) obtained through the Bluetooth array-based positioning represent a measurement vector, which is denoted by \({\varvec{Z}}_{k} = [x_{n} ,x_{e} ]^{T}\); thus, the system's measurement equation is given by:

Further, the measurement matrix is defined as follows:

In Eq. (19), \({\mathbf{V}}_{k}\) represents the measurement noise at a time \(k\).

Therefore, the complete prediction and update process can be written as:

Improved EKF algorithm with SVD and adaptive robustness

\({\mathbf{P}}_{k,k - 1}\) is a symmetric matrix. Over time, the number of iterations increases, which results in it no longer having a non-negative positivity. To solve this problem, assume that the rank of the matrix is \(e\), \(0 < e < 1\), and its eigenvalue is \( \sigma _{1}^{2} ,\quad \sigma _{2}^{2} ,\quad \ldots ,\quad \sigma _{n}^{2} \). So there is an orthogonal matrix that is similar to the diagonal matrix of \({\mathbf{S}}\). Assuming \({\varvec{V}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\varvec{V}}_{1} } & {{\varvec{V}}_{2} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), and \({\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\varvec{V}}_{2} = 0\), then the matrix can be written as follows:

Next, set \({\varvec{U}}_{1} = {\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\varvec{V}}_{1} {\varvec{S}}_{r}^{ - 1}\), and \({\varvec{U}}_{1}^{T} {\varvec{U}}_{1} = {\varvec{I}}\). Therefore, the \(r\) column vectors of \({\varvec{U}}_{1}\) are a set of unit orthogonal vectors. Then there is an orthonormal matrix \({\varvec{U}}_{2}\) such that \({\varvec{U}} = [\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\varvec{U}}_{1} } & {{\varvec{U}}_{2} } \\ \end{array} ]\). Therefore, the following formula holds:

From \({\varvec{U}}_{1} = {\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\varvec{V}}_{1} {\varvec{S}}_{r}^{ - 1}\), it can be obtained \({\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\varvec{V}}_{1} = {\varvec{U}}_{1} {\varvec{S}}_{r}\), which yields:

Further, since \({\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\varvec{V}}_{2} = 0\), it holds that \({\mathbf{U}}_{1}^{T} {\mathbf{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\mathbf{V}}_{2} = {\mathbf{U}}_{2}^{T} {\mathbf{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\mathbf{V}}_{2} = 0\).

Namely, it holds that:

In addition, since \({\varvec{P}}_{k,k - 1}\) is symmetric, the following formula holds:

Thus, \({\varvec{V}} = {\varvec{U}}\) and \({\varvec{V}}^{T} {\varvec{U}} = {\varvec{I}}\), which get:

Afterward, by setting \({\mathbf{D}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{S}}_{r}^{{}} } & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ \end{array} } \right]\), it can be obtained that:

Any matrix can be decomposed by SVD into the product of several simple matrices. At the same time, the original characteristics of the matrix are preserved. In the traditional KF algorithm, the state covariance matrix loses its non-negative positivity after many iterations. The decomposition of SVD can maintain its non-negative positivity and improve the accuracy.

The polarization factor of a circular array antenna can reflect the polarization mode of the signal source and also indicate the strength of the corresponding signal. Therefore, the polarization factor of a circular array antenna can serve as a basis for evaluating the positioning accuracy of a Bluetooth array. When factors such as occlusion lead to a decrease in system positioning accuracy, the polarization factor of the circular array antenna will also reflect corresponding changes. Therefore, introducing the polarization factor for filtering adaptation can better cope with the variability of indoor environments.

In a real indoor testing environment, the polarization mode of a signal source is unknown. Therefore, the least squares method is employed to estimate the polarization mode in this study. When a signal source is incident on an array antenna at an elevation angle \(\theta\) and an azimuth angle \(\varphi\), the polarization factor of the signal source can be expressed by:

At the current location, a frame of effective Bluetooth data is represented by \({\mathbf{y}}_{i}\), and the horizontal- and vertical-polarization directive vectors of the array antenna are represented by \({\mathbf{v}}_{h} (\theta ,\varphi )\) and \({\mathbf{v}}_{v} (\theta ,\varphi )\), respectively. The polarization factor can be estimated as follows:

where \({\mathbf{s}}(\theta ,\varphi ) = [\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{v}}_{h} (\theta ,\varphi )} & {{\mathbf{v}}_{v} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ \end{array} ]\), \({\mathbf{v}}_{h} (\theta ,\varphi ) = [\begin{array}{*{20}c} {a_{h1} (\theta ,\varphi )} & {a_{h2} (\theta ,\varphi )} & \cdots & {a_{hN} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ \end{array} ]\), and \({\mathbf{v}}_{h} (\theta ,\varphi ) = [\begin{array}{*{20}c} {a_{v1} (\theta ,\varphi )} & {a_{v2} (\theta ,\varphi )} & \cdots & {a_{vN} (\theta ,\varphi )} \\ \end{array} ]\); \(a_{n} (\theta ,\varphi )\) is a component related to the polarization type.

Solving the above equation can provide the polarization factor of the signal source when it is incident on the array antenna at the current location as follows:

The polarization factor correlates with the signal matrix to obtain the correlation matrix, which is expressed as follows:

For the range covered by the array antenna, the correlation matrix between the incident signals and the manifold matrix is \({\mathbf{C}}(\theta ,\varphi )\), and \(\varepsilon_{B}\) denotes the maximum value among all the elements of matrix \({\mathbf{C}}(\theta ,\varphi )\). This maximum value represents the self-assessment factor, and its larger value indicates a stronger correlation and a higher positioning accuracy. This serves as a criterion for determining whether the positioning result is normal or not, which can be written as:

where \(c\) represents the threshold. Its value is the experience value obtained from multiple static tests.

In the Kalman filter, the innovation vector is \({\mathbf{r}}_{k} = {\mathbf{Z}}_{k} - {\mathbf{H}}_{k} {\mathbf{X}}_{k,k - 1}\). Vector \({\varvec{r}}_{k}\) follows a Gaussian distribution. If there are no factors such as multipath, occlusion, then its mean is zero. However, if the signal is interfered by factors such as multipath and occlusion, its positioning error will also increase. At this point, the mean is considered to be \({\varvec{Z}}_{k} - {\varvec{Z}}_{k}^{{\text{T}}}\), where \({\varvec{Z}}_{k}^{{\text{T}}}\) is the actual position. Assuming that the covariance matrix of \({\varvec{r}}_{k}\) is \({\mathbf{N}}_{k} = {\mathbf{H}}_{k} {\mathbf{P}}_{k,k - 1} {\mathbf{H}}_{k}^{{\text{T}}}\), the verification information can be constructed as follows:

Replacing \({\mathbf{R}}_{cv,k}\) with \(\alpha_{k} {\mathbf{R}}_{cv,k}\) in formula 29 can improve the anti-difference performance of the filter. Then, the self-assessment factor of a Bluetooth array is compared with threshold value, and if \(\varepsilon\) is less than the threshold, indicates that the location result is abnormal, and vice versa. This way can be enhanced the robustness of filtering and improves positioning accuracy.

Using Sage–Husa filter can improve the accuracy of the filter. Suppose \(0 < b < 1\) is the forgetting factor, its formula is as follows:

where \(\beta_{k} { = (1} - {\text{b)/(1}} - {\text{b}}^{k + 1} {)}\).

The overall system workflow, incorporating the Bluetooth array positioning algorithm, is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Evaluation

In this study, the basic principle of Bluetooth array angle measurement is Angle of Arrival. Although smartphones use omnidirectional antennas, in actual environments where a signal source can be placed in different directions, the positioning results might vary. The positioning accuracy changes with the signal source’s position, is negatively correlated with the distance of the signal source and the positioning base station. Before verifying the effectiveness of the tracking algorithm, the Bluetooth array system positioning accuracy needs to be ensured. To this end, static testing of the signal source and self-rotation testing of the signal source were conducted in this study. Also, dynamic testing was performed only after the accuracy requirements in static and self-rotation testing had been met.

In certain indoor environments, the presence of furniture and other internal furnishings can make it challenging to conduct accuracy tests at different horizontal distances from a base station. Hence, static and rotation positioning tests were performed in open environments. In the position calculation process, the height was assumed to be known, and the base station layout height is substituted into Eq. (7). A relative coordinate system was defined using the center of base station as the origin. Figure 9 shows the test environment. Base station layout height is 2.4m. During the data collection process, each frame of data was collected over two loops, and each antenna collected eight data points. The central antenna, which was antenna number 9, served as a frequency estimation antenna, and the collected data were routed to the receiver through channel 1. The signal source was a Xiaomi 9 smartphone.

Static test results

As mentioned before, the positioning accuracy varies with a signal source’s location. Therefore, in this study, points at different distances from a base station were selected for static testing. For the static testing, points at a different horizontal distance from the base station, with the coordinates of (0, − 1), (1.5, 0), and (2, − 1.5) were selected. The results are shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12. Figures 10, 11 and 12a,b represent the horizontal two-dimensional positioning results of two consecutive frames of data; Figs. 10, 11 and 12c shows the cost function plot for a single frame of data; Figs. 10, 11, and 12d illustrates the variation curve of the circular-polarization factor for multiple continuous data frames.

Figure 10 shows the results of point (0, − 1). It can be observed that the x- and y-direction accuracy was 0.144 m and 0.09 m. This indicated good and stable positioning results without abrupt changes. The circular polarization factor curve in Fig. 10d shows that most polarization factors were larger than nine. Figure 11 shows the results of point (1.5,0). It can be observed that the x- and y-direction accuracy was 0.1 m and 0.14 m. Most polarization factors were larger than nine, albeit slightly lower compared to the (0, − 1) point. Figure 12 shows the results of point (2, − 1.5). At this point, the x- and y-direction accuracy was 0.714 m and 0.579 m. The reason for the lower accuracy at this point was due to a discontinuity in the data generated by the 22nd frame, which was possibly due to interference from the other signals. Therefore, the results from this frame were considered outliers. Excluding this frame, the x- and y-direction accuracy was approximately 0.382 m and 0.265 m. At this point, the elevation angle between the signal source and positioning base station is large, so a slightly lower accuracy was achieved, but it was still within 0.5 m. The circular polarization factor curve demonstrates that most polarization factors were greater than eight. When the 22nd frame data was disturbed, the polarization factor dropped below two.

Further, to visually represent the positioning results of the three points, the error statistics and CDF diagrams of the three points are shown in Fig. 13. The positioning error was calculated by \(\sqrt {\Delta x^{2} + \Delta y^{2} }\), where \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta y\) represented the errors of the current positioning point, respectively. In Fig. 13, it can be observed that the positioning errors of points (0, − 1) and (1.5, 0) were similar and outperformed those of point (2, − 1.5). Point (2, − 1.5) was close to the positioning range’s edge and its positioning accuracy was also better than 0.5 m. Therefore, the Bluetooth array could ensure high-precision static positioning within the coverage area.

Empirical source rotation positioning results

For the source spin test, this study selected point (1.5, 0) on the coordinate axis and point (2, − 1.5) off the coordinate axis, which was farther from the antenna in terms of horizontal distance, for testing. The two-dimensional positioning results and the corresponding polarization factor curve of the 200 frames of data are presented in Figs. 14 and 15. In the error graph for point (1.5, 0), it can be observed that the x-direction accuracy was high, having a value of approximately 0.14 m, and the z-direction accuracy was nearly 0.24 m, indicating good positioning results with only one discontinuity point; this was probably due to interference from the other signals. The x-direction positioning result was significantly affected by the source spin, showing a decreasing-then-increasing-then-decreasing trend. Meanwhile, the z-direction positioning result remained relatively stable with the source spin. The polarization factor curve shows that most polarization factors were higher than nine. However, during data interference, the polarization factor dropped below two. For point (2, − 1.5), the error graph reveals an x-direction accuracy of approximately 0.255 m and a y-direction accuracy of nearly 0.125 m. Therefore, for distant points, there were significant fluctuations in positioning accuracy for certain frames, and some of them reached over 0.5 m. The polarization factor curve shows that the majority of polarization factors were above six, while some points with a lower positioning accuracy had polarization factors below six.

The error statistics and CDF diagrams for the two test points are presented in Fig. 16. The graphs in Fig. 15 indicate that the positioning error for point (1.5, 0) was better than that for point (2, − 1.5), and the worst angular accuracy of the positioning results was better than 0.8 m. Therefore, for both points, the Bluetooth array at any angle could ensure high-precision positioning.

Further, to reflect the positioning accuracy more intuitively, this study analyzed the statistics of the static and source spin positioning results. The analysis results are shown in Table 1.

Empirical dynamic positioning results

The comprehensive analysis of the static tests and source spin tests indicated that the Bluetooth array could achieve high-precision positioning at different angles. The polarization factor varied significantly with the angle value, but it could reflect the positioning results’ quality. When the polarization factor was larger than six, the positioning results were generally good; however, when the polarization factor was less than two, the positioning results were incorrect. Therefore, the polarization factor could be used as a self-assessment factor for the accuracy of the Bluetooth array combined with the EKF. Based on this, dynamic positioning experiments were conducted. The test location was at the former site of the Chinese Academy of Surveying and Mapping The experimental environment was on the third floor. This test environment was selected because it has cluttered rooms and long, narrow corridors, and it is complex and diverse. The Bluetooth array system consisted of self-developed Bluetooth signal-receiving devices and backend processing algorithms. On the user end, a Xiaomi 9 mobile phone with the integrated indoor-outdoor positioning application developed on the Android Studio platform was used. The coordinates were unified Gauss plane coordinates in CGCS2000 coordinate system. The plan of the test site is shown in Fig. 17.

During the experiment, pedestrians carried mobile phones and walked along the path A4-A3-A2-A1-A4-A5-A6-A7. The output frequency of the Bluetooth array data was 1 Hz. Since all timing was based on the mobile phone’s time, and the Bluetooth array algorithm computation time was less than 2 ms, there was no need to consider time synchronization between the Bluetooth array and the PDR. The results of the Bluetooth array without integrating the PDR are shown in Fig. 18.

Due to the inevitable deviation from the preset trajectory when the pedestrians walked along the predefined path, using the preset trajectory as a reference was not entirely reliable. Therefore, an automatic tracking continuous dynamic positioning evaluation method using a total station was employed in this study to evaluate the Bluetooth array and fusion positioning results obtained indoors. The total station could not have line-of-sight visibility inside rooms and corridors simultaneously, so automatic tracking tests were conducted separately in rooms and corridors using the same total station. The measurement time of the total station was determined based on the time when the data were received by the computer. The computer time was synchronized with the times of the network and mobile phone, having a time synchronization error of less than 50 ms. Since pedestrian movement was slow, this time synchronization error could be ignored.

The dynamic positioning results obtained in the room and corridor are presented in Fig. 19, where Fig. 19a shows the dynamic positioning trajectory in the room, and Fig. 19b displays the dynamic positioning trajectory in the corridor. In Fig. 19, the blue asterisks represent the original output coordinates of the Bluetooth array; the red asterisks represent the reference trajectory coordinates output by the total station; the green plus signs indicate the coordinates fused by the EKF integrating the Bluetooth array and PDR; the blue plus signs are the coordinates fused by the SVD-EKF integrating the Bluetooth array and PDR. Since the total station had a relatively high data output frequency, its data were filtered. The total station’s coordinates in Fig. 19a and b denote the coordinates corresponding to the time tags selected based on the Bluetooth array data. In Fig. 19a and b, it can be observed that the RMS values of the Bluetooth array standalone system in the corridor and room were 0.665m and 0.286 m. After the EKF fusion, the RMS values in the room and corridor were 0.241 m and 0.422 m. Thus, the accuracy in the room improved by 0.045 m, and that in the corridor improved by 0.243 m. After the SVD-EKF fusion, the RMS values in the room and corridor were 0.236 m and 0.292 m. Therefore, the accuracy in the room improved by 0.05 m, and that in the corridor improved by 0.373 m. In the room, due to the inherently high positioning accuracy of the Bluetooth array, the two fusion methods showed comparable improvements in positioning accuracy. Due to the narrow layout of corridors, the multipath effect is exacerbated, and the number of base stations deployed is relatively limited. The proposed SVD-EKF fusion positioning method significantly outperformed the EKF in accuracy, and its positioning trajectory was smoother. These results indicated that compared to the EKF, the proposed SVD-EKF could significantly improve both robustness and accuracy, which makes it suitable for complex and variable indoor environments.

Based on the above-presented experimental results, the proposed indoor positioning method of dual-channel Bluetooth array angle measurement can achieve static positioning accuracy better than 0.6 m. When the positioning accuracy is reduced in a complex environment, can achieve dynamic positioning accuracy better than 1 m by the proposed Bluetooth array–PDR fusion positioning method. The SVD-EKF method proposed in this paper is compared with the traditional EKF has stronger robustness and environmental adaptability and can significantly improve the accuracy in a narrow corridor area. Consequently, the proposed method has a practical significance and can improve indoor positioning accuracy.

Conclusions

Currently, multi-source fusion positioning is one of the primary solutions to address the problems of low accuracy and poor system generalization capabilities in indoor positioning. This study proposes a Bluetooth array–PDR fusion positioning method based on the SVD-EKF. The SVD-EKF incorporates singular value decomposition and Bluetooth array polarization factors into the EKF, which enhances the robustness and environmental adaptability of the filtering algorithm. On the premise that the static positioning accuracy of a Bluetooth array is satisfied, the dynamic positioning accuracy of SVD-EKF and conventional EKF is compared in an NLOS environment.

The static positioning tests are performed at different distances, and the source spin tests are conducted in an open environment. The results show that the Bluetooth array angle measurement achieves high positioning accuracy in the coverage range. Near point positioning accuracy is 0.3m, far point positioning accuracy is 0.6m.

In addition, dynamic tests are performed in real-world environments. The results show that the positioning error of Bluetooth array system is less than 1m, with the Hausdorff distances of 0.82 m and 0.41 m for the corridor section and interior room section. The positioning error of the room is smaller than that of the corridor, which can be attributed to the narrowness of the corridor area, severe multipath effects from the walls, and the inability to perform multi-base station joint solutions.

Finally, accuracy testing for fusion positioning is conducted using a dynamic testing method with automatic tracking by the total station. The results show a 0.05m improvement in the accuracy of the SVD-EKF algorithm compared to the EKF algorithm in rooms with higher Bluetooth array positioning accuracy. In the corridor section, where the Bluetooth array system's positioning accuracy sharply declines, the proposed SVD-EKF fusion positioning method demonstrates significantly better accuracy than the EKF algorithm, achieving an improvement of 0.373 m and a smoother positioning result compared to the traditional EKF algorithm.

In conclusion, the proposed SVD-EKF algorithm exhibits stronger robustness and environmental adaptability compared to the traditional EKF algorithm and can achieve static and dynamic positioning accuracies of 0.6 m in the covered area.

This system has certain limitations, as it has made relatively few improvements to the PDR algorithm, making it difficult to fully leverage the advantages of single-base station positioning using Bluetooth arrays. Therefore, the enhancement of the PDR model will be the main focus of my subsequent research, including considerations for users' different motion states, postures, and various device placement positions. Additionally, I will continue my research on improving Kalman filter algorithms, refining the fusion positioning method for different abrupt situations. Lastly, I will also conduct research on the geometric configuration of base station deployment, aiming to reduce the number of base stations while ensuring accuracy, thereby lowering costs.

Data availability

The present dataset is released in the GitHub repository of the first author, and the URL is https://github.com/Chenhuilixynu/BLEPDR_data.

Abbreviations

- FFT:

-

Fast Fourier transform

- PDR:

-

Pedestrian dead reckoning

- SVD-EKF:

-

Singular value decomposition-extended Kalman filter

- EKF:

-

Extended Kalman filter

- GNSS:

-

Global navigation satellite system

- AOA:

-

Angle of arrival

- BLE:

-

Bluetooth low energy

- NLOS:

-

Non line of sight

References

Shin, B. et al. Motion recognition-based 3D pedestrian navigation system using smartphone. IEEE Sens. J. 16(18), 6977–6989. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2016.2585655 (2016).

El-Sheimy, N. & Li, Y. Indoor navigation: State of the art and future trends. Satell. Navig. https://doi.org/10.1186/S43020-021-00041-3 (2021).

Ji, W. et al. Multivariable fingerprints with random forest variable selection for indoor positioning system. IEEE Sens. J. 22(6), 5398–5406. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3103863 (2021).

Liu, J., Chen, R., Chen, Y., Pei, L. & Chen, L. iParking: An intelligent indoor location-based smartphone parking service. Sensors 12, 14612–14629. https://doi.org/10.3390/s121114612 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. NLOS mitigation in sparse anchor environments with the misclosure check algorithm. Remote Sens. 11, 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11070773 (2019).

Feng, D. et al. Kalman filter based integration of IMU and UWB for high-accuracy indoor positioning and navigation. IEEE Internet Things J. 7(4), 3133–3146. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.2965115 (2020).

Cao, X. et al. A universal Wi-Fi fingerprint localization method based on machine learning and sample differences. Satell. Navig. 001, 002 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Carrier phase ranging for indoor positioning with 5G NR signals. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.11772 (2021).

Jian, C. et al. A multisensor fusion algorithm of indoor localization using derivative Euclidean distance and the weighted extended Kalman filter. Sensor Rev. 42(6), 669–681 (2022).

Ruiz, A. R. et al. Accurate pedestrian indoor navigation by tightly coupling foot-mounted IMU and RFID measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 61(1), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2011.2159317 (2011).

Ebrahimi, A. & Czarnuch, S. Automatic super-surface removal in complex 3D indoor environments using iterative region-based RANSAC. Sensors 11, 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/S21113724 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Improved TOA estimation method for acoustic ranging in a reverberant environment. IEEE Sens. J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2020.3036170 (2020).

Xie, B., Tan, G. & He, T. SpinLight: A high accuracy and robust light positioning system for indoor applications. ACM https://doi.org/10.1145/2809695.2809713 (2015).

Liu, X., Guo, L. & Wei, X. Indoor visible light applications for communication, positioning, and security. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021(18), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1730655 (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. A robust dead reckoning algorithm based on Wi-Fi FTM and multiple sensors. Remote Sens. 11(5), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11050504 (2019).

Ye, F. et al. A low-cost single-anchor solution for indoor positioning using BLE and inertial sensor data. IEEE Access 7, 162439–162453. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2951281 (2019).

Guo, G. et al. Indoor smartphone localization: A hybrid WiFi RTT-RSS ranging approach. IEEE Access 7, 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2957753 (2019).

Zhou, R., Yang, Y. & Chen, P. An RSS transform-based WKNN for indoor positioning. Sensors 21(17), 5685. https://doi.org/10.3390/S21175685 (2021).

Kuang, J., Niu, X., Zhang, P. & Chen, X. Indoor positioning based on pedestrian dead reckoning and magnetic field matching for smartphones. Sensors 18(12), 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18124142 (2018).

Fan, Q. et al. Improved pedestrian dead reckoning based on a robust adaptive Kalman filter for indoor inertial location system. Sensors 19(2), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19020294 (2019).

Wang, B. et al. A novel weighted KNN algorithm based on RSS similarity and position distance for Wi-Fi fingerprint positioning. IEEE Access 8, 30591–30602. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2973212 (2020).

Thio, V. et al. Experimental evaluation of the forkbeard ultrasonic indoor positioning system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2021.3136261 (2021).

Bian, H., Li, Z. & Zhao, F. A method of indoor localization based on BLE4.0 protocol of using beacons. in International Conference on Mechanical, Information and Industrial Engineering (2015).

Chu, T. Simplified indoor localization using bluetooth beacons and received signal strength fingerprinting with smartwatch. Sensors 24, 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24072088 (2024).

Ciabattoni, L. et al. Real time indoor localization integrating a model based pedestrian dead reckoning on smartphone and BLE beacons. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-017-0579-0 (2017).

Bae, H. J. & Choi, L. Indoor positioning system with pedestrian dead reckoning and BLE inverse fingerprinting. Int. J. Sens. Netw. Data Commun. https://doi.org/10.4172/2090-4886.1000159 (2018).

Bai, L. et al. A low cost indoor positioning system using bluetooth low energy. IEEE Access 8, 136858–136871. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3012342 (2020).

Qiu, X., Wang, B., Wang, J., et al. AOA-based BLE localization with carrier frequency offset mitigation. in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCWorkshops49005.2020.9145137. (2020).

SIG. Bluetooth 5.1 Direction Finding: 2019 [S/OL]. [2019–09–20]. https://www.bluetooth.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/BTAsia/1145-NORDIC-Bluetooth-Asia-2019-Bluetooth-5.1-Di-rection-Finding-Theory-and-Practice-v0.pdf.

Huang, C. et al. A performance evaluation framework for direction finding using BLE AoA/AoD receivers. IEEE Internet Things J. 8(5), 3331–3345. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.3022032 (2020).

Zhen, J. et al. A high accuracy positioning method for single base station in indoor Emer-gency environment. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 45, 1146–1154. https://doi.org/10.13203/j.whugis2020012 (2020).

Li, C. et al. An indoor positioning and tracking algorithm based on angle-of-arrival using a dual-channel array antenna. Remote. Sens. 13(21), 4301 (2021).

Qian, Y. & Chen, X. An improved particle filter based indoor tracking system via joint Wi-Fi/PDR localization. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1, 32 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Distributed Kalman filter for UWB/INS integrated pedestrian localization under colored measurement noise. Satell. Navig. 001, 002 (2021).

Foxlin, E. Pedestrian tracking with shoe-mounted inertial sensors. IEEE Comput. Gr. Appl. 25(6), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2005.140 (2005).

Wang, Q. et al. Pedestrian dead reckoning based on walking pattern recognition and online magnetic fingerprint trajectory calibration. IEEE Internet Things J. 8(3), 2011–2026. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.3016146 (2020).

Gu, F. et al. Accurate step length estimation for pedestrian dead reckoning localization using stacked autoencoders. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 68(8), 2705–2713. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2018.2871808 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. An improved PDR localization algorithm based on particle filter. Comput. Inform. 39, 340–360. https://doi.org/10.31577/CAI_2020_1-2_340 (2020).

Poulose, A., Senouci, B. & Han, D. S. Performance analysis of sensor fusion techniques for heading estimation using smartphone sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 19(24), 12369–12380. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2019.2940071 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. An improved strong tracking Kalman filter algorithm for the initial alignment of the shearer. Complexity https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3172501 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Precise 3-D indoor localization based on Wi-Fi FTM and built-in sensors. IEEE Internet Things J. 7(12), 11753–11765. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.2999626 (2020).

Wu, F., Liang, Y., Fu, Y. et al. A robust indoor positioning system based on encoded magnetic field and low-cost IMU. in 2016 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium - PLANS 2016. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/PLANS.2016.7479703. (2016).

Poulose, A., Eyobu, O. S. & Han, D. S. An indoor position-estimation algorithm using smartphone IMU sensor data. IEEE Access 7, 11165–11177. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2891942 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank CASM for providing a rich experimental environment and convenient installation services. We thank Sun Yat-sen University for technical support.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2022YFC3005705).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHL (Chenhui Li) is the author of the algorithm, and all authors are involved in the research process and experimental verification. CHL (Chenhui Li) is responsible for the acquisition and analysis of Bluetooth data. The Bluetooth array positioning software code was written by JXW (Wu Jianxin) and Chenhui Li (CHL). The first draft of the manuscript was written by CHL (Li Chenhui) and then revised and commented on by JZ (Zhen Jie) and JXW (Wu Jianxin). All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Zhen, J. & Wu, J. An indoor positioning method based on bluetooth array/PDR fusion using the SVD-EKF. Sci Rep 15, 4579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88860-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88860-1