Abstract

Defect recognition is crucial in steel production and quality control, but performing this detection task accurately presents significant challenges. ConvNeXt, a model based on self-attention mechanism, has shown excellent performance in image classification tasks. To further enhance ConvNeXt’s ability to classify defects on steel surfaces, we propose a network architecture called ESG-ConvNeXt. First, in the image processing stage, we introduce a serial multi-attention mechanism approach. This method fully leverages the extracted information and improves image information retention by combining the strengths of each module. Second, we design a parallel multi-scale residual module to adaptively extract diverse discriminative features from the input image, thereby enhancing the model’s feature extraction capability. Finally, in the downsampling stage, we incorporate a PReLU activation function to mitigate the problem of neuron death during downsampling. We conducted extensive experiments using the NEU-CLS-64 steel surface defect dataset, and the results demonstrate that our model outperforms other methods in terms of detection performance, achieving an average recognition accuracy of 97.5%. Through ablation experiments, we validated the effectiveness of each module; through visualization experiments, our model exhibited strong classification capability. Additionally, experiments on the X-SDD dataset confirm that the ESG-ConvNeXt network achieves solid classification results. Therefore, the proposed ESG-ConvNeXt network shows great potential in steel surface defect classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steel, as an essential material in industrial production, is widely used in various fields such as construction, infrastructure, automotive, transportation, machinery, and industrial equipment1. However, during the actual production process, due to the influence of complex factors such as the manufacturing process and production environment, various defects may appear on the steel surface, including cracks, inclusions, rolled-in scales, and scratches. Accurate classification and identification of these defects can help analyze their formation causes and optimize the production process, ultimately improving product quality. This not only holds significant industrial application value but also has far-reaching theoretical significance2.

In the traditional identification of steel surface defects, two main methods are used: manual inspection and non-destructive testing3. Although manual visual inspection can intuitively detect defects, it is less efficient, more labor-intensive, and susceptible to subjective factors, which limits the consistency and accuracy of the inspection results. Non-destructive testing methods, such as ultrasonic testing, magnetic particle testing, and penetration testing, can identify surface defects without damaging the material. However, these methods have high requirements regarding the type of defects, inspection materials, and inspection environment, which limits their widespread application in practice4.

With the rapid development of computer technology, machine vision has overcome the shortcomings of traditional inspection methods by leveraging advantages such as fatigue resistance, low cost, high accuracy, and speed. It has gradually become the most effective choice for industrial inspection5. However, machine vision methods typically use industrial cameras to capture images and directly process them to obtain detection results. The processing methods include distortion correction, image denoising, image segmentation, etc., followed by the classification and detection of defective images using classifiers. The disadvantage of this approach is that the detection model is relatively simple and may not meet generalization requirements. Due to the complexity of steel surface defects in terms of area and shape, traditional image processing techniques have struggled to meet the demands of industrial detection. Unlike traditional machine vision methods, deep learning approaches utilize learning-based techniques6. Through the stacking of multi-layer neural networks, deep learning can fit high-dimensional functions and achieve distributed representation of input data. After training on many samples, deep learning can extract essential features and is characterized by high flexibility and superior fitting capabilities.

In intelligent manufacturing systems, industrial products typically have few defects, leading to an extremely unbalanced sample distribution in surface defect recognition tasks, which diminishes the deep learning model’s ability to recognize these categories effectively7. Meanwhile, traditional deep learning models often struggle with feature extraction, making it difficult to capture the subtle texture and shape features of the steel surface. Additionally, noise and background interference pose significant challenges in complex shooting environments. Moreover, with limited training data, the model is prone to overfitting, which negatively affects its generalization ability. To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel method for steel surface defect classification. First, to tackle the data imbalance problem, we employ data augmentation to address the current situation. Second, to resolve the insufficient feature information in the model, we propose a parallel multi-scale residual module to enhance the model’s ability to extract diverse features. To overcome the limitations in capturing subtle texture and shape features, we introduce a multi-attention mechanism to focus on key information while minimizing noise and background interference. During training, we use the AdamW optimizer and extend the dataset by combining multiple data augmentation techniques, which effectively alleviates the sample distribution imbalance and improves the model’s generalization ability. The results demonstrate that the proposed model excels in classification performance.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A parallel multi-scale residual module is proposed. This module extracts diverse discriminative features from the input image and fuses them to further enhance the model’s ability to capture various features.

-

2.

A serial approach to multiple attention mechanisms is proposed. We serialize an efficient local attention module, a lightweight, parameter-free attention module, and a global attention module after different convolutional modules. These modules utilize the extracted defect features to enable the model to focus on global discriminative features and use the information more efficiently to emphasize the defect itself.

-

3.

The model’s performance was evaluated using the NEU-CLS-64 dataset, which demonstrated that the model proposed in this paper has a strong ability to classify steel surface defects. First, the effectiveness of each sub-module was assessed through ablation experiments. Subsequently, feature visualization and result visualization experiments were conducted to examine the model’s classification effectiveness and its focus on defects. Our ESG-ConvNeXt network outperforms other methods in classifying surface defects on strips. Finally, in generalizability experiments, our proposed network also shows excellent results on the X-SDD dataset.

Related work

In recent years, the rise of deep learning technology has revolutionized the field of steel material surface defect detection. Deep learning-based methods can autonomously learn image features without the need for manually designed feature extraction algorithms8, significantly improving the accuracy and efficiency of defect detection. Common deep learning models include Convolutional Neural Networks9 (CNN), Generative Adversarial Networks10 (GAN), and object detection algorithms such as YOLO11, SSD12, and Faster R-CNN13. These algorithms can be trained on large image datasets to recognize defects of various types and sizes and can be adapted to different surface conditions of steel materials. However, online adaptive detection of steel surface defects remains a challenging task due to the diversity of defect classes14, low contrast between defects and the background, and complex texture backgrounds.

Wei et al.15 proposed an enhanced Faster R-CNN model that achieved significant improvements in the detection rate of small defects and the reduction of false alarms by combining weighted RoI pooling, deformable convolution, and the feature pyramid network (FPN). However, the study did not explore the model’s adaptability in various industrial scenarios with different defect types. Guan et al.16 introduced an improved deep learning network model for identifying steel surface defects through feature visualization and quality assessment, demonstrating significant improvements in classification accuracy and convergence speed compared to VGG19 and ResNet. However, further research is needed to enhance the detection of rare defects and the model’s generalization ability under small sample conditions. Zhao et al.17 proposed a new algorithm based on discriminative manifold regularized local descriptors (DMRLD) for the classification of steel surface defects, which constructs local descriptors through a learning mechanism and utilizes the manifold structure for feature extraction, thus improving classification performance. Feng et al.18 fused the ResNet50 and FcaNet networks, added the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module), and validated the algorithm on the X-SDD strip steel defect dataset, achieving a classification accuracy of 94.11%. To address the algorithm’s low classification performance for individual defects, the team applied ensemble learning for optimization, combining it with VGG16 and SqueezeNet on top of the original network, which increased the recognition rate of individual iron oxide pressed-in defects by 21.05% and the overall accuracy rate to 94.85%.

In a complex industrial production context, defects on the surface of hot-rolled strip steel are rare and diverse, making it very challenging to acquire defect images. Wang et al.19 proposed a transductive learning algorithm to address the problem of poor classification accuracy when only a small number of labeled samples are available. Unlike most inductive small sample learning methods, this algorithm trains new classifiers during the testing phase, enabling it to handle unlabeled samples in the dataset. Additionally, the team implemented simple fusion counting to extract more sample information, achieving a high classification accuracy of 97.13% on the NEU-CLS dataset with only one labeled sample. Yi et al.20 proposed a single-image model-based SDE-ConSinGAN method for surface defects in strip steel, trained using generative adversarial networks, to construct a framework for image feature cutting and stitching. The model aims to reduce training time by dynamically adjusting the number of iterations in different phases, and to emphasize the detailed defect features of the training samples by introducing a new resizing function and incorporating a channel attention mechanism.

Materials and methods

Dataset description

In this study, the NEU-CLS-6421 dataset, consisting of surface defects on hot-rolled strip steel from Northeastern University, was used. The dataset contains approximately 7000 images across nine defect categories: rolling scale, patches, cracks, pitting surface, inclusions, scratches, oil stains, pits, and rust. Each category includes hundreds to thousands of images, each with a size of 64 × 64 pixels. Figure 1 illustrates a random sample of images from each category.

Despite the availability of approximately 7000 samples in the dataset, there is an imbalance among the categories. Considering that images may encounter various factors during the collection process, such as different angles, changes in lighting, and interference from impurities, we applied data augmentation techniques such as rotation, adding random noise, and adjusting brightness to simulate various real-world scenarios and expand the dataset. After augmentation, the total number of samples reached 28,904.

Constructing network model

With the emergence of Vision Transformers22 (ViTs), they have gradually replaced convolutional neural networks (ConvNets) as the leading models for image classification23. However, when dealing with computer vision tasks such as object detection and image classification, the performance of pure ViTs often falls short. Hierarchical Transformers, such as Swin Transformer24, have incorporated prior knowledge from convolutional neural networks, allowing Transformers to serve as universal backbone networks in various visual tasks and demonstrating excellent performance. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of this hybrid approach is often attributed to the superiority of Transformers themselves rather than the inherent advantages of convolution. Recently, researchers have progressively aligned the design of standard ResNet25 with that of visual transformers, leading to the development of a scalable, pure convolutional neural network called ConvNeXt, aimed at improving the inference speed and accuracy of image classification tasks. Compared to the Swin Transformer, ConvNeXt exhibits superior performance in mechanical applications. Therefore, we have chosen ConvNeXt V226, a pure convolutional neural network, as the backbone and proposed our model to tackle the detection and classification of surface defect types in hot-rolled steel strips.

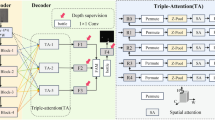

Overall structure of the network model

To accurately detect the types of defects on the surface of hot-rolled strip steel, we propose a network called ESG-ConvNeXt. This network is not only capable of effectively learning image features but also capable of classifying these images accurately. As shown in Fig. 2, the network consists of four main stages: Stage 1, Stage 2, Stage 3, and Stage 4. In the image preprocessing stage, a convolution kernel with a stride of 4 and a size of 4 × 4 is used for downsampling, and the image is resized to an input feature map of 224 × 224, which is then normalized by an LN layer. After each stage of processing, the dimension of the feature map is progressively reduced while the number of channels is increased, and the receptive field is expanded, ultimately outputting the key point location information of the defects on the strip surface. All stages except the first one consist of a downsampling layer and a modified ConvNeXt block, where the main function of the downsampling layer is to expand the receptive field while reducing the image resolution. The model structure is inspired by the Swin Transformer, and the ratio of the number of core blocks is modified from the standard 3:4:6:3 to 1:1:3:1. Replacing the Stem layer in the traditional ResNet model, the stride of the convolutional layer is increased from 2 to 4, the convolution kernel size is reduced from 7 to 4, and the maximum pooling layer is removed.

The training process is as follows: First, the training and test sets are divided in a ratio of 8:2; the training set is augmented with data, and the test set is normalized. Next, the ESG-ConvNeXt model is defined, the model parameters are initialized, and the optimizer and loss function are specified. Finally, the model is trained using the training set, and its performance is evaluated using the test set.

ConvNeXt module for multi-attention mechanisms

To overcome the limitations of standard convolutional operations in capturing long-range dependencies and focusing on important features, we integrate three different attention mechanisms: efficient local attention27 (ELA), parameter-free attention module28 (SimAM), and global attention mechanism29 (GAM) at key locations in each ConvNeXtV2 block, as shown in Fig. 3a. This hierarchical approach aims to progressively optimize the feature map to improve the model’s classification ability and robustness. We name our proposed model “ESG-ConvNeXtV2,” where “ESG” stands for the initials of the three attention mechanisms we integrate. This naming provides an intuitive reflection of the key components of the model and highlights its core strategy for improving feature representation.

Firstly, an efficient local attention (ELA) mechanism is introduced after the first convolution operation within each ConvNeXtV2 block. As shown in Fig. 3d, ELA employs strip pooling in the spatial dimension to acquire feature vectors in the horizontal and vertical directions while maintaining a narrow kernel shape to capture long-range dependencies and prevent the influence of irrelevant regions on the label prediction. This approach generates rich target location features in their respective directions. The ELA independently processes the feature vectors in each direction to obtain attention predictions, which are then combined through a product operation to ensure accurate location information for the region of interest.

In the first step of the Efficient Local Attention (ELA) mechanism, strip pooling is used to generate feature maps containing information about horizontal and vertical coordinates in the spatial dimension of the input tensor, and the RH × W × C capabilities denote the outputs of the convolutional blocks in terms of height, width, and the number of convolutional kernels, respectively. To apply strip merging, average merging is performed for each channel in both horizontal and vertical spatial scales: (H,1) denotes the horizontal direction and (1, W) denotes the vertical direction. Therefore, the output of the c-th channel at height h can be expressed by Eq. (1), and the output of the c-th channel at width w is expressed by Eq. (1).

In the first step of the Efficient Local Attention (ELA) mechanism, strip pooling is used to generate feature maps containing information about horizontal and vertical coordinates in the spatial dimension of the input tensor, with the RH × W × C capability denoting the output of the convolutional block, and H,W and C being the height, width, and number of convolutional kernels, respectively. To apply strip merging, average merging is performed for each channel at two spatial scales, horizontal and vertical: (H,1) denotes the horizontal direction and (1, W) denotes the vertical direction. Therefore, the output of the c-th channel at height h can be expressed by Eq. (1), and the output of the c-th channel at width w is expressed by Eq. (2).

To effectively utilize the surface defect information of hot rolled strip captured in the first step, a simple processing method is designed to apply 1D convolution to locally interact with two feature vectors in the second step. The size of the convolution kernel can be adjusted to represent the coverage of the local interaction. The generated feature vectors are processed by group normalization (Group Norm) and nonlinear activation functions to generate predictions of positional attention in both directions. The final positional attention is obtained by multiplying the positional attention in both directions.

Equation (3) represents the result of positional attention in the horizontal direction, and Eq. (4) represents the result of positional attention in the vertical direction, zh and zw are obtained from Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. σ is denoted as the nonlinear activation function, Gn denotes the extended and adopted attentional weight, and Fh and Fw denote the 1D convolutions, and to be more in line with the structure of our network, the convolution kernel of Fh and Fw is set to 5. Finally, the output Y of the ELA module is obtained by Eq. (5):

By applying Efficient Local Attention (ELA) after the first convolutional layer, we ensure that subsequent layers receive optimized inputs, thus improving the model’s ability to learn and generalize to the data.

Next, after the second convolution operation, we fused an attention mechanism module (SimAM) capable of estimating 3D weights. This module proposes a neuron-based energy function to compute attention weights by evaluating the importance of individual neurons, as shown in Fig. 3b. Meanwhile, it enhances feature extraction by focusing on the key information in the downsampling module to minimize the risk of overfitting and effectively capture discriminative features. The energy function is defined as shown in Eq. (6):

where t and xi are the target neuron and other neurons of a single channel input feature, i is the spatial dimensionality coefficient, (\(w_{t} x_{i} + b_{t}\)) and (\(w_{t} t + b_{t}\)) are the linear transformations of xi and t, and M = HxW is the number of neurons in a single channel, where H and W are the height and width of the input features, respectively. The analytical solution of the above equation is Eqs. (7) and (8):

where \(\mu_{t} = \frac{1}{M - 1}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{M - 1} {x_{i} }\) and \(\sigma_{t}^{2} = \frac{1}{M - 1}\sum\limits_{i}^{M - 1} {(x_{i} - \mu_{t} )^{2} }\) are the meaning and variance of all neurons in this channel except t. Thus, the minimum energy formula is shown in Eq. (9):

Equation (9) shows that the lower the \(e_{t}^{*}\) energy, the greater the difference between neuron t and the other neurons around it, and the more important it is for visual processing. Finally, the features are optimized for processing, as shown in Eq. (10):

where X is the input feature and E groups all the energy functions across energy and space. Adding a sigmoid limits excessively large values in E without affecting the relative importance of each neuron. The SimAM attention module is introduced after the second convolution to focus the model on information-rich neurons, reducing noise and suppressing interference from irrelevant features such as background, thus enhancing the feature representation of the network.

After the final convolution operation of each ConvNeXtV2 block, a Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) is fused. This mechanism retains information to enlarge the global cross-dimensional interaction and amplifies the global dimensional interaction features while reducing the information. The GAM assigns different weights to different dimensions of the input data, to achieve the distinction of different feature attention levels. The whole process is shown in Fig. 3c.

From the figure, the input feature F1 is obtained after a series of intermediate operations, and the output feature F3 is obtained. The intermediate state is defined as F2, and its formula is shown in Eqs. (11) and (12), respectively. Where MC denotes channel attention and MS denotes spatial attention.

The channel attention module uses 3D alignment to maintain information across three dimensions. After two layers of Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to amplify the correlation of the channels across dimensions, the inverse alignment is performed, and the result is obtained by Sigmoid function. This is shown in Fig. 4.

After the channel attention module generates the feature map, the spatial attention module further compresses the feature map. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 5, the input features are first convolved by 7 × 7 to reduce the number of channels, thus reducing the computation; then they are operated by r (reduction ratio), followed by another 7 × 7 convolution to increase the number of channels, and finally the results are obtained by the Sigmoid function.

By adding a Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) after the last layer of convolution, it is possible to ensure that the feature representation is optimized throughout the processing, allowing the model to make more accurate predictions before passing through the fully connected layers.

Parallel processing strategy

To address the potential loss of detailed information during the downsampling process, we propose a new parallel network structure, as shown in Fig. 6. This structure is based on the design principles of the Residual Block and Inverted Residual Block, with two types of networks reconstructed.

First, in the residual block-based structure, we apply two 3 × 3 convolution operations to the input feature maps and introduce a 1 × 1 convolution to increase the number of channels, thereby enhancing the richness of the feature representation. To avoid the issue of zero output caused by the ReLU activation function when handling negative values, we use the PReLU activation function instead of ReLU. This ensures that no information is lost during negative inputs, while also enhancing the training effect and model performance, enabling better handling of data diversity.

Second, in the inverted residual block-based design, the input feature maps are first expanded by a 1 × 1 convolution, followed by high-dimensional feature extraction using 3 × 3 depthwise separable convolution. To ensure that the output feature map maintains the same size and dimension as the input, we use a 1 × 1 convolution for dimensionality reduction. Since the inverted residual structure may have limitations in capturing complex features, we introduce the SimAM attention mechanism after dimensionality reduction to address this limitation and improve feature representation.

By processing these two network structures in parallel with the previously mentioned ConvNeXt module containing the attention mechanism, we significantly enhance the overall performance and generalization of the model.

Improved activation functions

The original ConvNeXt network used GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) as an activation function. GELU is a type of activation function that contains regularization and is a smoothed variant of ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), which introduces the idea of stochastic regularity to alleviate the problem of vanishing gradients. The GELU activation function takes the form of Eq. (13):

where x is used as the neuron input and erf(x) is the error function, a non-fundamental function. The larger x is, the more likely it is that the activation output x will be preserved, while the smaller x is, the more likely it is that the activation will result in a 0. The result of the activation is the same as that of a neuron.

Since the GELU activation function affects the convergence of the hard saturated region during the computation, we consider changing the activation function to avoid this situation. The ReLU function is defined as max (ax, x), the problem of which is that when the input is less than zero, the gradient is zero, which results in neurons not being able to learn through backpropagation. The Sigmoid function is computed by the formula \(\frac{1}{{1 + e^{ - x} }}\), where x is the input value. The output range of the Sigmoid function is (0, 1). This function is affected by the gradient saturation problem during computation, i.e., the gradient tends to zero at large or small input values, which leads to gradient vanishing and gradient explosion. The PReLU (Parameter Rectified Linear Unit) activation function is defined as max (ax, x) (0 < a < 1). It is showing in Fig. 7. Compared to the above activation function, PReLU solves the hard saturation problem of GELU at (x < 0)30. Therefore, we replace the GELU activation function with the PReLU activation function to increase the nonlinear capability of the proposed network model. The improved activation function can convey the defect information on the surface of hot-rolled strip more effectively at each stage, which improves the recognition performance and classification effect of the model.

The improvements of downsampling module

The structure of the downsample module in the ConvNeXt model is shown in Fig. 8a, which contains a normalization layer and a convolutional layer. Downsampling reduces the size of the extracted feature map and filters out less influential features and redundant information while retaining key feature information. In addition, it helps to reduce computational cost and memory consumption.

However, when the learning rate is too large, the gradient update may cause the new weights to become negative, leading to disabled neurons. If the weights are negative, any positive input multiplied by these weights will produce a negative value, and the output will be zero after applying activation functions such as ReLU, Sigmoid, or GELU, resulting in the “neuron death” problem. To address this issue, we introduce the PReLU activation function based on the original downsampling structure. By adjusting the parameter α, better nonlinear features can be learned. The improved structure is shown in Fig. 8b.

Experiments and results

Experimental configuration

The proposed ESG-ConvNeXt is compared with other state-of-the-art methods, all of which are implemented using Python version 3.8.1 and built on the PyTorch 1.13.1 framework. All experiments were conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04, equipped with an AMD EPYC 7542 32-core processor and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 graphics card.

During training, the ESG-ConvNeXt model uses the Cross-Entropy Loss function. The AdamW optimizer and warm-up strategy were employed for training. The hyperparameters of all models were set with an initial learning rate of 0.0001 and a batch size of 64, with a total of 100 training epochs. Additionally, all experiments were repeated five times to ensure the stability of the models.

Model training

To evaluate the effectiveness of the ESG-ConvNeXt model in classifying surface defects on hot-rolled strips, we compared it with DenseNet12131, MobileNetV332, InceptionV333, ConvNeXtV2, Vision Transformer, and Swin Transformer models using the hot-rolled strip surface defects dataset for training. The experimental results were then compared and analyzed.

Figure 9 illustrates the trend of model validation accuracy across different training epochs. From the figure, it is evident that our proposed model achieves an accuracy of 99.12%, followed by DenseNet121 and Swin Transformer with 97.86% accuracy, while MobileNetV3 has the lowest accuracy at 84.97%. The results indicate that our proposed model achieves high validation accuracy, demonstrating its strong performance.

Evaluation metrics

This experiment uses accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and FPS to assess model performance. Accuracy represents the overall correctness of the model’s predictions; however, it may not be an ideal metric for evaluating performance in cases with an unbalanced dataset. Precision measures the accuracy of the positive samples predicted by the model, while recall indicates the probability of correctly predicting a positive sample among all actual positive samples. FPS is used to evaluate the speed at which the deep learning network processes images per second. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score for binary classification are defined using Eqs. (14), (15), (16), and (17):

True Positive (TP) refers to the number of correctly predicted positive samples; False Positive (FP) is the number of negative samples that were predicted as positive; True Negative (TN) indicates the number of correctly predicted negative samples; and False Negative (FN) refers to the number of positive samples that were predicted as negative.

Performance comparison of different models

In training the ESG-ConvNeXt model, we use images from the test set to evaluate the classification performance. We compared the proposed ESG-ConvNeXt model with InceptionV3, ConvNeXtV2, MobileNetV3, DenseNet121, Vision Transformer (VIT), and Swin Transformer (Swin-T) models, mainly based on accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score. The results are shown in Table 1, where our model achieves 97.5% in accuracy, 96.6% in precision, 95.9% in recall, and 96.1% in F1 score. Compared to the other six models, our model shows significant improvement in all four metrics and is at the highest level among these seven networks. Nevertheless, in terms of FPS, our detection speed is not significantly improved, mainly due to the decrease in inference speed during the network design process to retain more detailed information and better capture small target defects.

Confusion matrix analysis

As shown in Fig. 10, the confusion matrix34 of our proposed ESG-ConvNeXt model is compared with other convolutional neural network (CNN) models. In this confusion matrix, the horizontal axis represents the predicted categories, while the vertical axis represents the true categories. The labels “cr”, “gg”, “in”, “pa”, “ps”, “rp”, “rs”, “sc”, and “sp” on both axes correspond to the nine defect types in our dataset, specifically cracks, pits, inclusions, patches, pitting surfaces, rust, scale, scratches, and oil stains. According to the results, under the same experimental parameters, our proposed ESG-ConvNeXt model exhibits fewer misidentifications of defects compared to the geometric feature-based strip surface defect classification methods. Notably, only one out of 153 scratch images is misidentified as rust scale. In contrast, the other models show a higher number of misidentifications. These results further validate the robustness of the ESG-ConvNeXt model.

Ablation experiment

To investigate the effect of different modules on classification results, we incorporate the parallel processing module, the attention mechanism module and the activation function into the ConvNeXt model for ablation experiments, respectively. The effectiveness of each module on model enhancement is evaluated by accuracy, F1 score, recall and precision. The experimental results are shown in Table 2, where ‘↑’ indicates the improvement in accuracy relative to the original ConvNeXt model.

From the details of the table, the modules effectively mitigate the problem of lower accuracy encountered when using the ConvNeXt model by parallel processing, adding the Attention Mechanism module and improving the activation function. Under the influence of these modules, our model shows a significant improvement in comparison to the benchmark model, with an accuracy of 97.5%, precision of 96.6%, recall of 95.9%, and F1 score of 96.1%. These modules help improve the model performance and make it more suitable for classifying surface defects on hot rolled strip. By incorporating these modules, our model improves 4.7% and 6.0% in accuracy and precision, respectively, relative to the original model, providing more reliable and accurate results for the task of classifying surface defects on hot-rolled strip steel.

Figure 11 demonstrates the trend of each module incorporation with respect to the change in the number of training epochs. From the figure, each module has significantly improved the classification of surface defects on hot rolled strips.

Feature visualization

T-SNE is a dimensionality reduction method to visualise data by downscaling it to 2D or 3D35. In classification tasks, T-SNE is used for dimensionality reduction to show clustering between features. Our ESG-ConvNeXt model is visualised with six models, DenseNet121, MobileNetV3, InceptionV3, ConvNeXtV2, Vision Transformer, and Swin Transformer, in the reduced feature space with dimension 2. The random number seed is set to 42. As shown in Fig. 12, the figure represents the different colours of the nine defects in our dataset, which are: cr, gg, in, pa, ps, rp, rs, sc, and sp. Their corresponding defects are cracks, pits, inclusion, patches, pitting surface, rust, scale, scratches and oil stains. in the figure, features with the same defect class are clustered together, while features with different defect classes are clearly separated. We can clearly see that the proposed ESG-ConvNeXt network outperforms the other six networks in clustering on each defect category, with MobileNetV3 having the worst clustering effect. This shows that the ESG-ConvNeXt model can produce a more discriminative feature map compared to the other models, further proving its superiority.

Visualization of results

We visualize this through Gradient Class Activation Heat Map (Grad-CAM)36, a method that generates a class activation map by performing a weighted summation of the feature map to show the importance of a particular region in the image to the classification result. This approach helps to provide insight into the generalization capabilities of our model. Grad-CAM can analyze the region of interest of the model under a particular class and determine whether the model has learned appropriate features or information from that region. We applied the ESG-ConvNeXt model along with six other models (DenseNet121, MobileNetV3, InceptionV3, ConvNeXtV2, Vision Transformer, and Swin Transformer) to the visualization of regions of interest for defects on steel surfaces, and the raw images were randomly selected. By using these images as inputs to the respective networks, we obtained feature maps of the parts that affect the classification scores. As shown in Fig. 13, the darker the color in the class activation map, the greater the contribution of the region to the recognition result. The ESG-ConvNeXt model is more accurate in determining the region of interest, and the region of interest is more concentrated on the defect locations on the steel surface, which enhances the matching ability of the model. Compared with other models, our model can focus more on specific points rather than overly focusing on cracks and their surrounding larger background regions. This improvement effectively enhances the detection of small targets and demonstrates the strong learning ability of our model for steel surface defect detection.

Generalizability experiments

To verify the generalization ability of the ESG-ConvNeXt algorithm, this paper chooses to use the publicly available dataset Xsteel (X-SDD), which can also be used for the classification of steel surface defects, as shown in Fig. 14. This dataset contains seven types of defect images totaling 1360 images, including 238 images of entrapment slag, 397 images of red tin, 122 images of tin grey, 134 images of surface scratches, 63 images of plate system oxidation, 203 images of finishing roll marks, and 203 images of temperature system oxidation. After data enhancement, our total number of samples reached 5440.

The results are shown on Fig. 15 when the running environment is kept consistent. The red dash line indicates the trend of our model on the X-SDD dataset with an increasing number of trainings. By comparing the accuracy of our model ESG-ConvNeXt with other models, it can be observed that the accuracy of our proposed model is still at the highest level.

Then, we compared the models on accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score and FPS, respectively. As shown in Table 3, compared to the benchmark model ConvNeXtV2, our proposed model improves 14.7%, 16.2%, 17.6%, and 17.3% on these four parameters, respectively. Compared with Table 1, the evaluation metrics of the other six models are not stable, while our model has been relatively stable in these evaluation metrics, which further demonstrates the good generalization performance of our model.

Conclusion

In this paper, we address the issues of limited generalization performance and insufficient adaptability in complex environments that have been encountered in previous studies on the detection and classification of steel surface defects. To overcome these challenges, we propose a network model based on ESG-ConvNeXt. The method enhances defect detection and classification by extracting feature maps at different depths within the network. The main conclusions are as follows: the inclusion of ELA, SimAM, and GAM in each module for optimizing the feature maps significantly improves the classification ability and robustness of the model. Furthermore, the model’s performance and generalization ability are effectively enhanced by the parallel processing structure. Additionally, the PReLU activation function is introduced to alleviate the “neuron death” problem during the downsampling process. A series of experiments conducted on the strip surface defect dataset demonstrate that the ESG-ConvNeXt model significantly outperforms other network models in terms of generalization. Under the same experimental conditions, the ESG-ConvNeXt model achieves an accuracy of 97.5%, precision of 96.6%, recall of 95.9%, and F1 score of 96.1% on the augmented test set. These experimental results show that the ESG-ConvNeXt model outperforms other network models in both classification ability and robustness, highlighting the effectiveness of this model improvement approach in the detection and classification of steel surface defects.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available at http://faculty.neu.edu.cn/songkechen/ zh_CN/zdylm/263,270/list/ and https://github.com/Fighter20092392/X-SDD-A-New-benchmark.

References

Wen, X., Shan, J., He, Y. & Song, K. Steel surface defect recognition: A survey. Coatings 13, 17 (2022).

Yi, L., Li, G. & Jiang, M. An end-to-end steel strip surface defects recognition system based on convolutional neural networks. Steel Res. Int. 88, 1600068 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Multi-Scale Lightweight Neural Network for Steel Surface Defect Detection. Coatings 13, 1202 (2023).

Gupta, M., Khan, M. A., Butola, R. & Singari, R. M. Advances in applications of non-destructive testing (NDT): A review. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 8, 2286–2307 (2022).

Masci, J., Meier, U. & Ciresan, D. et al. Steel defect classification with max-pooling convolutional neural networks. in proceedings of the 2012 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN). (IEEE, 2012).

Qi, S., Yang, J. & Zhong, Z. A review on industrial surface defect detection based on deep learning technology. in 2020 The 3rd International Conference on Machine Learning and Machine Intelligence 24–30 (ACM, Hangzhou China, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3426826.3426832.

Bai, D. et al. Surface defect detection methods for industrial products with imbalanced samples: A review of progress in the 2020s. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 130, 107697 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Farman, H. & Jan, Z. Deep learning methods and applications. In Deep Learning: Convergence to Big Data Analytics 31–42 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3459-7_3.

Chua, L. O. CNN: A vision of complexity. Int. J. Bifurcation Chaos 07, 2219–2425 (1997).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144 (2020).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.02640 (2016).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2016 Vol. 9905 (eds Leibe, B. et al.) 21–37 (Springer, 2016).

Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. in 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 1440–1448 (IEEE, Santiago, Chile, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2015.169.

Zheng, X., Zheng, S., Kong, Y. & Chen, J. Recent advances in surface defect inspection of industrial products using deep learning techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 113, 35–58 (2021).

Wei, R., Song, Y. & Zhang, Y. Enhanced faster region convolutional neural networks for steel surface defect detection. ISIJ Int. 60, 539–545 (2020).

Guan, S., Lei, M. & Lu, H. A steel surface defect recognition algorithm based on improved deep learning network model using feature visualization and quality evaluation. IEEE Access 8, 49885–49895 (2020).

Zhao, J., Peng, Y. & Yan, Y. Steel surface defect classification based on discriminant manifold regularized local descriptor. IEEE Access 6, 71719–71731 (2018).

Feng, X., Gao, X. & Luo, L. A ResNet50-based method for classifying surface defects in hot-rolled strip steel. Mathematics 9(19), 2359 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Surface defects classification of hot rolled strip based on few-shot learning. ISIJ Int. 62(6), 1222–1226 (2022).

Yi, C. et al. Steel strip defect sample generation method based on fusible feature GAN model under few samples. Sensors 23(6), 3216 (2023).

He, Y., Song, K., Meng, Q. & Yan, Y. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, 1493–1504 (2020).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929 (2021).

Maurício, J., Domingues, I. & Bernardino, J. Comparing vision transformers and convolutional neural networks for image classification: A literature review. Appl. Sci. 13, 5521 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14030 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385 (2015).

Woo, S. et al. ConvNeXt V2: Co-designing and scaling ConvNets with masked autoencoders. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2301.00808 (2023).

Xu, W. & Wan, Y. ELA: Efficient local attention for deep convolutional neural networks. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2403.01123 (2024).

Yang, L., Zhang, R.-Y., Li, L. & Xie, X. SimAM: a simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks.

Liu, Y., Shao, Z. & Hoffmann, N. Global attention mechanism: Retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2112.05561 (2021).

Li, D., Zhai, M., Piao, X., Li, W. & Zhang, L. A ginseng appearance quality grading method based on an improved ConvNeXt model. Agronomy 13, 1770 (2023).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., van der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06993 (2018).

Howard, A. et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.02244 (2019).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.00567 (2015).

Düntsch, I. & Gediga, G. Confusion matrices and rough set data analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1229, 012055 (2019).

Linderman, G. C., Rachh, M., Hoskins, J. G., Steinerberger, S. & Kluger, Y. Efficient algorithms for t-distributed stochastic neighborhood embedding. Nat. Methods 16, 243–245 (2019).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 128, 336–359 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. designed the algorithm model and wrote the main manuscript text, L.Z. and C.Y. prepared and pre-processed image data of strip surface defects, L.Z. and Y.J. investigated related researchers and design the program, L.Z. provided the computing resource and validated the experimental results, and Z.E. revised and verified the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Liu, Z., Zhang, E. et al. An ESG-ConvNeXt network for steel surface defect classification based on hybrid attention mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 10926 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88958-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88958-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A defect recognition method based on ITLPP and multi-feature fusion matrix

Scientific Reports (2025)