Abstract

This research investigates the design of a nanofiltration (NF) system based on a nanocomposite membrane containing graphene oxide (GO) for the demineralization of sweet whey and the modeling the NF process. The effects of various process variables, including, transmembrane pressure (TMP), Reynolds number, feed pH, and temperature, on the rejection of the minerals were surveyed. Consequently, the recovery of whey proteins from industrial whey using fabricated membranes in a cross-flow membrane module was also investigated. Among the input variables, the pH of the whey solution has the greatest effect on membrane flux and salt rejection performance. In the dead-end filtration system, the highest flux was achieved for the GO-modified membrane under laboratory conditions with a pressure of 10 bar and a pH of 6. The dynamic flux behavior of whey output and salt rejection from whey was modeled using convolutional neural network (CNN) machine learning tools. Linear and non-linear correlations demonstrated that the CNN model correlates well with experimental data on dynamic flux (R2–1.00). Overall, this study on dynamic flux and rejection of minerals from whey using CNN modeling can improve optimal conditions for whey demineralization and reduce laboratory testing costs by predicting the results of untested experimental variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whey, as a by-product of cheese factories, is the liquid that remains after fat and casein removing from milk during the cheese-making process1. There are two types of whey: sweet whey and acid whey. Sweet whey is produced from enzyme cheeses and has a pH of 5.6,while acid whey, resulting from acid cheese production, has a pH of less than 5.12. Whey is a highly polluted wastewater due to the presence of organic and mineral substances, which also give it a very high chemical oxygen demand (COD) of approximately 76,000 ppm and a biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) of approximately 40,000 ppm. Additionally, whey has twice as much ash as milk, which makes it difficult to use extensively in food formulations. The product of sweet whey demineralization can serve as a basis for food products such as powdered milk, ice cream, and soft drinks containing whey. Thus, whey demineralization expands its use in the food industry while addressing environmental pollution issues3. Numerous techniques can be employed to demineralize whey, including electrodialysis, ion exchange, nanofiltration (NF), and reverse osmosis4. The use of NF for whey processing has recently received attention due to the unique advantages of this technique, including ease of operation and reduced energy consumption. NF process is used to separate salts while preserving beneficial organic components, such as lactose and protein during whey demineralization3. Polymeric membranes ensure high permeate flux and salt rejection percentage under operating conditions. Polysulfone is one of the most popular choices for preparing polymeric membranes is, due to its mechanical strength, chemical, and thermal resistance, stability in various pHs, and biocompatibility5. However, limitations such as low flux and membrane fouling, have promoted researchers to explore nanostructures in the membrane matrix. One promising nanostructure is graphene oxide (GO). GO, with its layered structure and polar functional groups, can increase the hydrophilicity of the membrane and reduce the fouling problem, and on the other hand, is very effective in improving membrane performance6,7,8 .

It should be noted that in whey protein filtration, salt transport is a complex phenomenon influenced by several parameters such as membrane properties and process variables, including feed properties, transmembrane pressure (TMP), cross-flow velocity, and tangential velocity9.

The ideal conditions for achieving lactose concentration and whey demineralization were found by Uribe Cuartas using NF membranes for whey ultrafiltration in a diafiltration mode with water addition10. Studies have also examined energy efficiency in sweetened osmosis-treated whey desalination using electrodialysis11, and explored how operational parameters impact permeate flux reduction in cross-flow microfiltration of whey. Findings indicate that Reynolds number and operational pressure positively affect optimal permeate flux, with compatibility improving as pressure increases12.

Maria et al. (2023) conducted a study on membrane ultrafiltration (UF) of whey to recover whey proteins and remove water as much as possible from the permeate and to predict and control the reduction of permeate flux in a cross-flow ultrafiltration device using a step-by-step approach and comparing different artificial neural networks following a genetic algorithm as an optimization strategy13. Yugara’s 2022 study compared process variables for whey protein recovery using polysulfone membranes. Cake layer formation was found to be the most significant factor, and the effect of pH on the membrane flux and protein removal performance was understood. A machine learning convolutional neural network (CNN) has been used to model whey permeate flux, demonstrating its potential for regulating flow rate sensors and improving whey recovery efficiency14. In 2017, Cabrera et al. used response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural networks5 to create prediction models for the reverse osmosis desalination process. The ANN model was valid across all feed salt concentrations and addressed RSM model limitations with four nonlinear input variables15.

In another study, the functional and antifouling properties of polymer NF membranes based on polyethersulfone (PES) polymer has been investigated. The surface modified membranes significantly improved salt separation and hydrophilicity, increasing the salt separation rate from 68 to 94%. The adsorption property of the chitosan polymer and GO nanosheets in contact with the feed solution was also reported. However, the amount of water flux passing through the membrane decreased due to the coating of the polymer layer and the increase in the thickness of the separator layer. The water contact angle also decreased due to the improvement of hydrophilicity and surface affinity due to the deposition of the hydrophilic chitosan layer and GO nanosheets16.

The main objective of this study is to investigate the feasibility of using modified nanocomposite membranes containing single-layer GO for sweet whey demineralization while developing a model capable of identifying complex patterns in NF dynamics. The influence of different process variables (membrane pressure, temperature, feed pH, and Reynolds number) on whey demineralization and membrane flux is investigated in the designed CNN. The results of this study lead to an improvement in the performance of whey NF membranes and can be implemented and utilized on an industrial scale.

Materials and methods

Materials

The chemicals used in this study include PES from BASF (Germany), polyethylene glycol 6000 from Merck, N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone (NMP), hydrochloric acid (HCl) from Merck. (Germany), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and single-layer GO from Nano United States, which has a density of 1.9 g/cm2, a molecular weight of 4.239 g/mol, and a purity percentage of 99.9.

Fresh whey was obtained from the cheese production line of the Pegah West Azerbaijan Company. This whey is derived from the traditional cheese production process and has a pH ranging from 5.6 to 5.8. The pH of the whey obtained from the traditional cheese production line was measured using a laboratory pH meter. A conductivity meter was used to determine the concentration of the initial minerals in the whey. HCl and NaOH were prepared to adjust the pH of the whey.

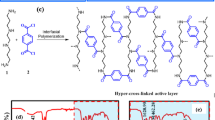

Synthesis of the nanocomposite membrane

To fabricate a suitable membrane with nanopore-sized pores and a flow rate that matches the goals of the research, PES membranes are first synthesized by the phase inversion method. Subsequently, the nanocomposite membranes are prepared with varying ratios of GO nanoparticles to increase the membrane’s hydrophilicity and improve fouling resistance. In order to overcome concentration polarization effects and membrane fouling on the intended outputs (solution flux and salt rejection), a variety of operational parameters and feed characteristics will be assessed and researched. For this purpose, the polymer (15 wt%) was poured into the solvent in a closed container and stirred for 24 h until it was completely dissolved. The required amount of polyethylene glycol (PEG) (30 wt% of polymer) was added to the solution and stirred again for 1 h. The prepared solution was kept in a static condition for 1 h to allow the bubbles to escape, and then it was cast on a clean glass with the desired thickness. Finally, the polymer layer was immersed in the coagulation bath (cooled distilled water) to separate the polymer membrane from the glass surface. The membrane was kept in a water bath for 24 h to remove the solvent residues, and then it was dried. The percentage of materials used to achieve the optimal formulation is shown in Table 1. Also, the schematic for the construction of pure PES membranes is illustrated in Fig. 1-a.

GO nanoparticles were incorporated into the matrix to investigate their effect on the membrane performance. For the preparation of nanocomposite-modified membranes, initially, 15 wt% of PES was mixed with 30 wt% of PEG respect to the polymer, inside a vessel containing NMP and stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 24 h at 40 °C. Different percentages of single-layer GO were added to the desired membrane solutions and placed in an ultrasonic bath for 2 h. Each mixture was then spread onto a smooth glass surface with a thickness of 150 to 200 micrometers, and distilled water was used as a non-solvent to separate the membrane from the glass. The schematic diagram of the stages of preparation of modified nanocomposite membranes is shown in Fig. 1-b. The prepared formulations of nanocomposite membrane are listed in Table 2.

Furthermore, analytical instruments utilized in this study include Field Emission Scanning Electron (FESEM) analysis device model III MIRA, Tescan-VEGA (Czech Republic), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis device model S Mobile Nanosurf (Switzerland), FTIR analysis device model Thermo Avatar (USA), ARE VELP heater stirrer (Italy), digital balance with four decimal places model Toledo Mettler (Switzerland), desktop conductivity meter model 86,505-AZ (Taiwan), micrometer for measuring membrane thickness, four-sided rectangular film stretcher with thicknesses of 50, 100, 150, and 200 micrometers, dead-end membrane filtration system for NF membrane testing with auxiliary equipment such as filtration cell and nitrogen gas capsule, pH meter model ST2100 from Ohaus (Switzerland), Soner203 ultrasonic bath (Taiwan).

In the construction of NF membranes based on PES, the phase inversion method is utilized. In this method, factors such as polymer, solvent, and non-solvent type, composition of the casting solution, coagulation bath, temperature of the casting solution and coagulation bath, and ambient humidity affect the structure and characteristics of the produced membranes. The most important parameter in membrane fabrication is the concentration of the casting solution. Therefore, various solutions were initially prepared for the construction of pure PES membranes, according to Table 1. Finally, a composition of 15 wt% polymer, 30 wt% PEG with respect to the polymer, and 8.05 g of NMP was deemed acceptable.

The hydrophilicity of each membrane is determined by measuring the contact angle of water. The contact angle (CA) measurement was performed using the drop shape analysis system VCA-OPTIMA. Using a syringe, three droplets with a volume of 4 µl were placed on the surface of the membranes to measure the static contact angle of the droplet, and the contact angle was measured. Additionally, FTIR analysis was used to investigate the presence of nanoparticles in the membrane matrix as well as identify the polymer used in membrane fabrication. Then, in FESEM analysis, the morphology of the cross-sectional and surface of the prepared membranes was examined. For this purpose, small pieces of the membranes were fractured in the liquid nitrogen and then coated with gold to form a thin and conductive layer. The samples were placed on a sample holder for imaging, and the analysis was performed. AFM analysis was used for precise analysis of morphology and surface roughness. For AFM imaging, the membranes were cut into 1 × 1 cm sizes, attached to a slide, and images were captured using the AFM device.

In this research, experiments were conducted under variable transmembrane pressure (TMP), pH, temperature, and Reynolds number using a dead-end filtration system, and changes in flux and salt rejection under different conditions were investigated. In dead-end filtration, the fluid passes through the membrane, and particles larger than the pore size of the membrane are retained on the membrane surface.

In order to improve the removal of minerals and the recovery of whey protein from whey solution using a convolutional neural network, the performance of a pure PES membrane is compared with a modified nanocomposite membrane with single-layer GO in a dead-end filtration system (laboratory scale).

Experimental setup

The experimental design of the conducted studies involved applying various levels of influential parameters using the response surface methodology and the Design Expert software to enhance data quality and reduce unnecessary experiments. This design was performed with four inputs (TMP, temperature, pH, and Reynolds number) and two outputs (flow rate at different time intervals and rejection of minerals), employing factorial and central composite designs with two and five repetitions, respectively.

Optimizing process variables has a significant impact on controlling membrane-salt interactions and thereby improving filtration performance under optimal energy conditions. The effect of various process variables such as feed pH, TMP, temperature, and Reynolds number (affected by flow pattern) on the performance of sweet whey protein filtration was evaluated. The effect of pH was investigated within the range of 4.6 to 6. The process temperature ranged from 20 to 40 °C. The Reynolds number in the stirred cell is directly related to the cell radius (r) and angular velocity (ω). The cell radius was set at 2 centimeters, and the stirrer speed ranged from 300 to 1000 revolutions per minute. Then, the Reynolds number was calculated for the dead-end cell.

For the filtration studies, a laboratory-scale dead-end NF device (Nanofiltration cell, USA) was used. The effective membrane area in this filtration device is 7.065 cm2. Prior to laboratory studies, the PES membrane was pressurized with distilled water for 4 h under constant high-pressure conditions to compact it. The flux of pure water was calculated using Eq. (1) and measured by changing the pressure.

Q: seepage flow rate (m3/s). A: effective cross-sectional area of the membrane (m2).

To investigate the concentration of salts in both permeate (Cp) and retentate (Cr) environments, the electrical conductivity of samples was measured at a temperature of 20 °C using a Conductometer. Since the electrical conductivity of a solution is strongly dependent on the ambient temperature, all samples were first kept at 20 °C for 30 min before measurement. Subsequently, measurements were taken. Finally, the percentage of mineral salt rejection was estimated using Eq. (2).

In CNN architecture, data of each input variables such as TMP, Reynolds number and feed pH were initialized by neuron connections through weighted input parameter such as weights (Wij) and bias (bi). The generalized representation of output function of neuron8 to input and weighted input are expressed in Eq. (3).

where xj and n are the input variables and number of input variables, respectively. Wij is the interconnected weight of i and j th neuron. λ is the activation factor. Activation function is a stimulating factor in conversion of weighted inputs into output function for each neuron.

One-layer convolutional neural network method is used to train datasets and convolutionary layers. The prediction of the CNN model for share dynamic performance is assessed using statistical parameters such as Coefficient of Determination (R2) and mean squared error (MSE). The statistical parameters were determined using the following equations:

where \({y_k}\) and \({\hat {y}_k}\) are the experimental flux and model predicted flux, respectively. N is the size of the dataset.

CNN modeling, training, and performance evaluation

Dataset preparation

Artificial neural networks and the Python programming language will be used for process modeling in order to forecast the dynamic behavior of the NF process. For training the networks, a version of the gradient descent algorithm was utilized. In the hypothesis of this design, CNN consists of an input layer, a convolutional layer, a fully connected layer, and an output layer. Generally, CNN requires a large dataset to cope with overfitting and ensure accurate predictions. Then, the fitted experimental dataset was randomly split into training and testing data. 75% of the initial experimental data were used for training, and the remaining percentage was used for testing.

Artificial neural networks and the Python programming language will be employed for process modeling to forecast the dynamic behavior of the NF process. A version of the gradient descent algorithm was utilized for training the networks. In this design, the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) consists of an input layer, a convolutional layer, a fully connected layer, and an output layer. Generally, CNNs require a large dataset to mitigate overfitting and ensure accurate predictions. The fitted experimental dataset was then randomly split into training and testing data, with 75% of the initial experimental data used for training and the remaining 25% allocated for testing.

Neural network design

Modeling with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is inspired by the neural networks of the human brain, involving the training of input data through neurons to achieve an optimal solution. The CNN model consists of three main structures: the input layer, the hidden layers, and the output layer (Fig. 2). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the CNN architecture includes an input layer that receives the input data, a convolutional layer with 64 filters and a kernel size of 3 that extracts local features, a MaxPooling layer with a window size of 2 to reduce dimensionality and increase efficiency, and a Flatten layer that transforms the extracted features into a 1D vector.

The ReLU activation function is employed in the hidden layers, while a linear activation function is used for the output layer. L2 regularization with a rate of 0.001 and dropout techniques are applied to prevent overfitting. For training, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm is utilized with a learning rate of 0.001 and a momentum of 0.9. The dataset is split in a ratio of 75–25 between training and testing sets.

To optimize the 1D CNN model, several experiments were conducted to tune hyperparameters. These hyperparameters included the number of filters in the convolutional layer, kernel size, learning rate, momentum, and dropout rate. The number of filters for the convolutional layer was determined experimentally; different values (such as 32, 64, and 128) were tested, with the best value (64) selected based on the minimum error observed in the validation set. The kernel size was set to 3 due to its effectiveness in extracting local features from the data.

As part of the SGD optimization process, various learning rates (such as 0.001, 0.005, and 0.01) were evaluated, with a rate of 0.001 identified as optimal. The momentum was also maintained at 0.9 to facilitate faster and more stable convergence.

The main advantage of CNN is that output data are also considered input data to identify optimal solutions for more complex and regular applications. Therefore, CNN is preferred in this study to model the dynamics of whey permeate flow over time. Python software was used for the simulation. In this neural network, input data at three different levels, including pH (4.6, 5.3, 6), sample temperature (20, 30, 40), Reynolds number (1290, 2791, 4292), and TMP (5, 7.5, 10) were considered as network inputs to evaluate the best conditions for achieving flux and salt rejection in whey permeate. Then, experimental laboratory data and results were used to train and test the artificial neural network. Therefore, the data were first divided into two parts: training data and testing data. 75% of the data were considered training data, and 25% were considered testing data. The testing data are used separately to evaluate the model, and during the training process, these data are not involved, and the model does not see them. This approach is for accurate and realistic model evaluation. To prevent model errors in assigning importance to certain parameters that have larger numbers and neglecting other parameters, the data were standardized. For this purpose, the MinMaxScaler function from the scikit-learn library was used, and all data were standardized to a range between zero and one.

The main advantage of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is that the output data can also be considered input data, which helps identify optimal solutions for more complex and regular applications. Therefore, CNNs are preferred in this study to model the dynamics of whey permeate flow over time. Python software was used for the simulation.In this neural network, input data at three different levels were considered as network inputs: pH (4.6, 5.3, 6), sample temperature (20, 30, 40), Reynolds number (1290, 2791, 4292), and Transmembrane Pressure (TMP) (5, 7.5, 10). These inputs were evaluated to determine the best conditions for achieving flux and salt rejection in whey permeate.Experimental laboratory data and results were then used to train and test the artificial neural network. The data were first divided into two parts: training data and testing data. 75% of the data were designated as training data, while 25% were reserved for testing. The testing data were used separately to evaluate the model; during the training process, these data were not involved, ensuring that the model did not have prior exposure to them. This approach supports accurate and realistic model evaluation.To prevent errors in the model due to the varying scales of certain parameters—where parameters with larger numerical values might be assigned undue importance while others are neglected—the data were standardized. For this purpose, the MinMaxScaler function from the scikit-learn library was employed, standardizing all data to a range between zero and one.

Statistical and optimization methods

For building the neural network model, the sequential function from the Keras library was utilized, which consists of 8 dense layers: input, dropout, embedding, MaxPooling1D, and batch normalization. This model was implemented on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i5 CPU processor and 16 gigabytes of RAM memory, running on Windows 11. In designing the intelligent model, a one-dimensional convolutional neural network and fully connected layers were employed. The ReLU activation function was utilized in this model, and the linear activation function was used in the output layer. The Mean-Squared-Error loss function was employed, and for optimization, Adam, Nadam, and RMSprop methods with a learning rate of 0.001 were used. Since the data in this experiment were numerical, the Conv1D neural network was utilized in the model. In this study, the convolution layer consisted of 64 neurons with a kernel size of 3 and a dilation rate of 1. During the model training phase, 200 epochs were used for training iterations. Additionally, in the model evaluation section, the MSE and R2-Score evaluation metrics were utilized. After analyzing the data and categorizing them into training and testing sets with a ratio of 75 to 25, the constructed model using the one-dimensional convolutional neural network was evaluated using the testing data. The model achieved 100% accuracy with an R2-Score metric in predicting the examined materials using the four selected features, and the loss function reached 0.44 using the MSE, which is considered acceptable and superior compared to the results of similar studies and articles based on the investigation results.

For building the neural network model, the Sequential function from the Keras library was utilized, which consists of eight dense layers: input, dropout, embedding, MaxPooling1D, and batch normalization. This model was implemented on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i5 CPU and 16 gigabytes of RAM, running on Windows 11. In designing the intelligent model, a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (CNN) and fully connected layers were employed. The ReLU activation function was utilized in this model, while the linear activation function was used in the output layer. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function was employed, and for optimization, the Adam, Nadam, and RMSprop methods with a learning rate of 0.001 were used. Since the data in this experiment were numerical, the Conv1D neural network was utilized in the model. In this study, the convolution layer consisted of 64 neurons with a kernel size of 3 and a dilation rate of 1. During the model training phase, 200 epochs were used for training iterations. Additionally, in the model evaluation section, the MSE and R² Score evaluation metrics were utilized. After analyzing the data and categorizing it into training and testing sets with a ratio of 75 to 25, the constructed model using the one-dimensional convolutional neural network was evaluated using the testing data. The model achieved 100% accuracy with an R² Score metric in predicting the examined materials using the four selected features, and the loss function reached 0.44 using MSE, which is considered acceptable and superior compared to the results of similar studies and articles based on the investigation results.

Results and discussion

Microscopic examination of the membranes

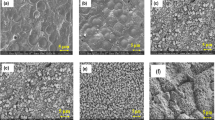

The FESEM images presented in Fig. 3 depict a layered structure with stacked sheets, indicating the widespread presence of GO. The surfaces exhibit large dimensions, likely resulting from the expansion of interlayer spacings or the delamination of layers due to severe oxidation. FESEM images of GO with different magnifications are shown in Fig. 3. The layered structure of GO sheets with smooth surfaces can be seen well in the images. These plates have a low thickness in nanometer dimensions. The layered structure of GO, along with functional groups on its surface, helps to actively remove substances from the membrane containing it. To examine the structure and morphology of the top surface layer and cross-sectional section of the fabricated membranes and the effect of adding GO, FESEM analysis was utilized. The results of the analysis are provided in Figs. 4 and 5, corresponding to the surface and cross-sectional images of the membranes, respectively. The images are presented with two different magnifications for better clarity.

On the surface of the GO-containing membrane, pores were created, and numerous fine particles were visible, indicating the presence of GO nanostructures. The presence of porosity and pores can also be observed at higher magnifications on the membrane surface. In the cross-sectional image of the neat PES membrane, sponge-like porous structures are depicted, and no foreign bodies are observed on the walls of the pores at higher magnifications. In contrast, in the membrane containing GO, in the cross-sectional morphology, finger-like pores appeared, and at higher magnifications, GO particles were recognizable (Fig. 4). The neat PES membrane has a smooth surface without any impurities. However, at higher magnification, protrusions of the same polymer material are visible, attributed to the uneven edge of the film casting in some areas (Fig. 5).

The water contact angle

To determine the surface hydrophilicity of the membrane, the contact angle of water droplets with the membrane surface was measured, and the results of this test are presented in Fig. 6. The results indicate that the use of GO nanoparticles leads to a decrease in the contact angle of the nanocomposite membranes (57°) compared to the pure membrane (65°). This reduction can be attributed to the presence of functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and epoxy on the surface of GO nanosheets, which enhance the interaction between water molecules and the membrane surface.

FTIR analysis

FTIR analysis was utilized to identify the functional groups present in both the pure membrane and the membrane modified with GO and its output consists of spectra containing distinctive peaks across a range of wavelengths. The peak positions are used in the identification of functional groups. The results are depicted in Fig. 7. Distinct peaks for PES as the membrane matrix appear at 3091, 2996, 1582, 1486, 1239, and 1148 cm–1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of aromatic C-H bonds, aliphatic C-H bonds, double bonds C=C present in the aromatic ring, and the stretching vibrations of the S = O double bonds, respectively. In the sample of the nanocomposite membrane containing GO, these peaks are also observed, and additionally, a distinct peak appears at 1710 cm–1, related to the C=O double bond present in GO. The presence of this additional peak confirmed the incorporation of GO into the matrix and the surface of the membrane.

AFM results

To investigate the surface morphology of the membranes and obtain information about surface roughness, AFM images of the membrane surfaces for two samples, a pure PES membrane and a PES membrane containing GO, were obtained and presented in Fig. 8. The results reveal that the pure PES membrane has a smooth surface with minimal roughness, whereas the membrane containing GO exhibits higher protrusions and depressions, resulting in greater surface roughness. This roughness may arise due to the presence of GO nanostructures on the surface. These findings are consistent with observations from FESEM images of the membrane surfaces.

The salt rejection and permeate flux

In Tables 3 and 4, the experimental design and the results related to the salt rejection percentage and whey solution flux in the dead-end filtration device using a pure PES membrane and the membrane modified with GO under various temperature, transmembrane pressure, Reynolds number, and pH conditions are presented. According to the results obtained in Tables 3 and 4, it is observed that under similar experimental conditions, the permeate flux increased with an increase in process temperature. The permeate flux increased by 29.3% as the temperature of the feed increased from 20 to 40 °C. The increase in permeate flux due to temperature rise is attributed to the decrease in feed viscosity and the increase in molecular diffusion coefficient. The increase in flux with temperature rise can also be justified by the increased mobility of polymer chains in polymer membranes, leading to a decrease in membrane resistance to mass transfer. It was found that the permeate flux of the NF process increases with temperature and an increase in pressure difference17. On the other hand, with increasing temperatures, the ability of membranes to retain salts decreased. In an experimental study, the groundwater NF process was investigated within the temperature range of 10 to 30 °C. The water flux at 30 °C was 1.5 times higher than at 10 °C. In their study, the rejection of monovalent ions (sodium, chloride, and potassium) significantly decreased within the specified temperature range, while the rejection of divalent ions (calcium, magnesium, and sulfate) was hardly affected by temperature18. In another study conducted by Schaep et al., the observed changes in ion passage are interpreted based on the increase in salt diffusion coefficient with temperature, while Nilsson et al. justify their observations based on membrane charge effects19.

To compare the performance of pure PES membranes and nanocomposite membranes containing GO nanostructures, the sample with the optimal result (with the highest salt rejection rate) was studied. The highest rejection was obtained in run 2 with the following the following conditions: T = 30 °C, TMP = 7.5 bar, pH = 5.3, and Re number = 4292.

Based on the data in Tables 3 and 4, the amount of rejection in the nanocomposite membrane increased by 23% and reached from 21% in the pure PES membrane to 31% in the nanocomposite membrane. This increase was due to the active effect of nanostructures on the absorption of salts. GO has hydroxyl and carboxylic acid functional groups that can play a role in the chelating of cations. On the other hand, GO with a layered structure was also effective in blocking the passage of cations and increasing the rejection of salts.

Permeate flux is directly related to the pressure difference across the membrane surface17. The results obtained from other studies showed that with an increase in the driving force of the process, the permeate flux increases. Abbas, A. et al. observed that at constant concentration and temperature, with an increase in process pressure in reverse osmosis from 20 to 60 bar, the permeate flux increased17.

From Tables 3 and 4, it can be observed that the flux increases with pressure for both types of membranes. With an increase in applied pressure, the fluid flow resistance decreases. The highest flux values were observed for pure PES and modified membranes (5.4 Kg/m2h and 6.75 Kg/m2h, respectively) at 10 bar pressure, while the lowest flux values were obtained (2.69 Kg/m2h and 3.33 Kg/m2h) for pure and modified membranes, respectively, at 5 bar pressure in the filtration system’s closed end.

The graph of flux changes over time for two samples is shown in Fig. 9. As can be seen, the initial flux of the nanocomposite membrane was higher than that of the pure PES membrane. The flux improvement in the nanocomposite membrane was due to the increased hydrophilicity of the membrane, which facilitated the passage of water through the pores of the membrane. Examining the trend of flux changes over time showed that the rate of flux reduction was higher in the pure membrane. Condensation of the porous structure of the membrane due to the application of pressure and the occurrence of the fouling phenomenon are the effective factors in reducing the flux with the passage of time in the membranes. In the nanocomposite membrane, the addition of GO to the structure improved the mechanical strength of the membrane, and less condensation occurred. On the other hand, with the increase in the hydrophilic nature of the membrane, the amount of protein absorption on the surface of the membrane and fouling decreased, and as a result, less flux loss was seen in the nanocomposite membrane.

Researchers have stated that the initial reduction in permeate flux is likely due to the formation of a concentration polarization layer near the membrane surface, which acts as secondary resistance, leading to a decrease in permeate flux. It is evident that the thickness of this layer is influenced by factors such as pressure difference, flow velocity, and temperature20. The maximum permeate flux in this study was measured at 8.37 kg/m2h under operational conditions with a temperature of 40 °C, a pH of 4.6, an operational pressure of 10 bar, and a Reynolds number of 4292. Studies indicate that flux varies with distinct input variables and also exhibits complex nonlinear behavior over time. This is undesirable in downstream industrial applications.

pH

NF membranes have functional groups that can be charged based on the pH of the pH of the solution in contact with the membrane surface. Most available NF membranes have a negative charge at neutral pH, with an isoelectric pH in the range of 3–421. pH affects membrane hydrophilicity, membrane charge, and membrane fouling, and consequently membrane performance22. As observed from Tables 3 and 4, an increase in pH leads to a noticeable increase in flow rate. The isoelectric point of whey is 4.6. When the pH of whey is less than 4.6, the solution becomes positively charged. The solubility of proteins reaches its lowest point at the isoelectric point because proteins lose their solubility at this pH. pH, net protein charge, and electrostatic interaction between proteins are influenced by pH23. Beta-lactoglobulin, the main component of milk, constitutes about 50% of the weight of whey and 12% of its total protein content, with an isoelectric point of 5.18. Beta-lactoglobulin can complex with monovalent and divalent metal ions. When the pH is higher than the isoelectric point, Na+ can complex with the carboxyl and imidazole of beta-lactoglobulin24. In this experiment, by adjusting the pH of whey, a noticeable difference in the salt rejection of whey was observed at the isoelectric point of whey proteins. It can be seen that adjusting the pH of whey to 4.6 resulted in the highest salt rejection from whey. This fact can be explained by the protein’s isoelectric point theory. At the isoelectric point of whey protein, the interaction between the protein and ions is weak. Therefore, more ions can be separated from whey. Thus, under these conditions, salts can be easily removed through the NF process.

As the pH increased, the acidic groups in the polymer structure of the membrane and the modified GO were hydrolyzed, and the hydrophilicity of the membrane increased. This increase in hydrophilicity improved the flux. However, due to the creation of chelating groups, the effect of these groups on salt cation adsorption has increased, and rejection has improved.

TMP and Reynolds number

With an increase in TMP difference, the amount of salt passage through the membrane surface increases, which is consistent with the results obtained by other researchers who have investigated the effect of pressure difference on salt rejection during NF. In both pure and modified membranes, the average flow rate increased with increasing Reynolds numbers, from 1290 in the laminar range to 4292 in the turbulent flow range. At pH 4.6 under maximum membrane pressure and constant temperature conditions, the average whey flux for Reynolds number 1290 was 5.34 kg/m2h, and for Reynolds number 4292, it was 6.78 kg/m2h. This increase was mainly limited by the increase in agitation speed and cross-flow velocity, which led to increased turbulence in the closed-end cell. Increasing Reynolds number at high stirring speeds reduced the deposition of protein molecules on the membrane surface. This phenomenon leads to an increase in forced convection and back diffusion of salts from the membrane solution to the bulk25. At pH 4.6 under maximum membrane pressure and constant temperature conditions, the salt rejection percentages for whey salts were observed to be 18% for the pure membrane at a Reynolds number of 1290 and 24% for the modified membrane at a Reynolds number of 4292. These experiments demonstrated a relative improvement in salt rejection with an increasing Reynolds number.

CNN model

In this study, the purpose of using the CNN model is to obtain optimal conditions on high production scales. Therefore, various parameters have been considered in the design of the experiment, and finally, for unknown conditions, the optimal parameters are determined by the model. One-dimensional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been used as a modeling tool to predict flux patterns based on various input variables. Overall, the ambiguous dataset available in other sections has made machine learning a suitable tool for finding solutions to industrial problems. The challenge of using machine learning techniques on datasets with a small number of samples is that it encompasses a very limited number of observations and is also prone to overfitting. Therefore, the median role plays an important role in presenting a solution for the final success of such applications. Developing an appropriate model to predict precise process conditions is essential for whey filtration.

Figures 10 and 11 depict the accuracy and error graphs of the model corresponding to the modified and pure membranes. The CNN model predicted the data well with both experimental flux datasets trained and tested for both pure and modified membranes. Furthermore, other statistical parameter values, such as MSE values, had a logical correlation with the predicted CNN model.

The obtained values indicate that the model has a strong ability to predict the actual values. Additionally, the scatter plots comparing the predicted and actual values (see Scatter Plot) demonstrate good agreement between the predictions and the actual values (refer to Fig. 12). Furthermore, the optimal conditions based on the highest salt rejection rate were identified as follows: best temperature: 30 °C, TMP: 7.5 bar, pH: 5.3, and Reynolds number: 4292.

R2-score graphs of pure and modified membranes.

The predicted CNN model for dynamic flux in the present study was compared with other membrane applications found in articles. As seen in Table 5, the predicted model for dynamic flux demonstrated satisfactory results with an R2 accuracy of 80% using minimal training datasets. Therefore, it can be inferred from these metrics that a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (CNN) can serve as a suitable membrane modeling technique for predicting membrane performance, as it can effectively work with a limited number of experiments in the dataset.

Compared to other traditional and modern methods, the CNN model performed better due to its ability to learn nonlinear and local features. The results presented in the article clearly demonstrate this superiority.

Conclusion

In the current study, de-mineralized whey was successfully extracted from the original whey solution using a dead-end filtration system. A nanocomposite PES membrane containing GO was used in this system to remove salts. An analysis was done on how process variables affected the flow and salt rejection from whey. The protein structure, membrane flux, and salt rejection from whey were all impacted by the feed’s pH. Better salt rejection from whey was found at pH levels above its isoelectric point, while higher pH levels were found to cause an increase in flux and a decrease in whey salt rejection. Flux increased as TMP increased. Furthermore, for both pure and modified membranes, the CNN demonstrated a strong correlation with experimental membrane flux dynamics.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: Data will be available on request. If someone wants to request the data from this study, should be contact with Ms. Mina Rezapour (minarezapour@yahoo.com).

References

Ferchichi, M., Crabbe, E., Gil, G. H., Hintz, W. & Almadidy, A. Influence of initial pH on hydrogen production from cheese whey. J. Biotechnol. 120, 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.05.017 (2005).

Saddoud, A., Hassaïri, I. & Sayadi, S. Anaerobic membrane reactor with phase separation for the treatment of cheese whey. Bioresour. Technol. 98, 2102–2108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2006.08.013 (2007).

Atra, R., Vatai, G., Bekassy-Molnar, E. & Balint, A. Investigation of ultra- and nanofiltration for utilization of whey protein and lactose. J. Food Eng. 67, 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.04.035 (2005).

Prosekov, A. J., r., E. U., Budrik, V., Botina, S. & Agarkova, E. J. On ways demineralization of whey. Int. J. Appl. Fundam.Res. 1, 3 (2013).

Stannett, V., Koros, W. J., Paul, D. R., Lonsdale, H. K. & Baker, R. W. Recent advances in membrane science and technology. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1979, 69–121 (1979).

Janjhi, F. A. et al. Recent advances in Graphene Oxide-based membranes for heavy metal ions separation. ChemBioEng Reviews. 9, 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/cben.202200015 (2022).

Jatoi, A. H. et al. Functionalized graphene oxide-based lamellar membranes for organic solvent nanofiltration applications. RSC Adv. 13, 12695–12702. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA00223C (2023).

Anand, A., Unnikrishnan, B., Mao, J. Y., Lin, H. J. & Huang, C. C. Graphene-based nanofiltration membranes for improving salt rejection, water flux and antifouling–A review. Desalination 429, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.12.012 (2018).

Corbatón-Báguena, M. J., Álvarez-Blanco, S. & Vincent-Vela, M. C. Ultrafiltration of whey: membrane performance and modelling using a combined pore blocking–cake formation model. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 1891–1900. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.5446 (2018).

Cuartas-Uribe, B. et al. A study of the separation of lactose from whey ultrafiltration permeate using nanofiltration. Desalination 241, 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.11.086 (2009).

Merkel, A., Voropaeva, D., Fárová, H. & Andrey, Y. High effective electrodialytic whey desalination at high temperature. Int. Dairy J. 108, 104737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2020.104737 (2020).

Rezaei, H., Zokaee, F. & Fouladitajar, A. Effects of operating parameters on fouling mechanism and membrane flux in cross-flow microfiltration of whey. Desalination 274, 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2011.02.015 (2011).

Gaudio, M. T., Curcio, S., Chakraborty, S. & Calabrò, V. Application of Artificial neural networks for modelling and control of Flux decline in Cross-flow Whey Ultrafiltration. Processes 11, 1287 (2023).

Yogarathinam, L. T. et al. Performance evaluation of whey flux in dead-end and cross-flow modes via convolutional neural networks. J. Environ. Manage. 301, 113872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113872 (2022).

Cabrera, P., Carta, J. A., González, J. & Melián, G. Artificial neural networks applied to manage the variable operation of a simple seawater reverse osmosis plant. Desalination 416, 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.04.032 (2017).

Moghadassi, A., Bagheripour, E., Hosseini, S. M. & Parvizian, F. Surface modification of PES Nanofiltration membrane by Chitosan-GO Nano-plates coating for reduction of fouling and performance enhancement. J. Petroleum Res. 29, 46–60. https://doi.org/10.22078/pr.2018.3295.2518 (2019).

Abbas, A. & Al-Bastaki, N. Modeling of an RO water desalination unit using neural networks. Chem. Eng. J. 114, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2005.07.016 (2005).

Schaep, J. et al. Removal of hardness from groundwater by nanofiltration. Desalination 119, 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-9164(98)00172-6 (1998).

Nilsson, M., Trägårdh, G. & Östergren, K. The influence of pH, salt and temperature on nanofiltration performance. J. Membr. Sci. 312, 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2007.12.059 (2008).

Rice, G., Barber, A., O’Connor, A., Stevens, G. & Kentish, S. Fouling of NF membranes by dairy ultrafiltration permeates. J. Membr. Sci. 330, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2008.12.048 (2009).

Li, N. N., Fane, A. G., Ho, W. S. W. & Matsuura, T. Advanced Membrane Technology and Applications (Wiley, 2008).

Nanda, D., Tung, K. L., Li, Y. L., Lin, N. J. & Chuang, C. J. Effect of pH on membrane morphology, fouling potential, and filtration performance of nanofiltration membrane for water softening. J. Membr. Sci. 349, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2009.12.004 (2010).

Zhang, H., Chen, X., Dan, T. & Dong, J. Traditional Chinese fermented dairy Foods. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Fundam. Pract. 2014, 493–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8841-0_8 (2014).

Yorgun, M. S., Balcioglu, I. A. & Saygin, O. Performance comparison of ultrafiltration, nanofiltration and reverse osmosis on whey treatment. Desalination 229, 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.09.008 (2008).

Verma, S. P. & Sarkar, B. Analysis of flux decline during rhamnolipid based micellar-enhanced ultrafiltration for simultaneous removal of cd + 2 and crystal violet from aqueous solution. J. Water Process. Eng. 33, 101048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.101048 (2020).

Nandi, B., Moparthi, A., Uppaluri, R. & Purkait, M. Treatment of oily wastewater using low cost ceramic membrane: comparative assessment of pore blocking and artificial neural network models. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 88, 881–892 (2010).

Soleimani, R., Shoushtari, N. A., Mirza, B. & Salahi, A. Experimental investigation, modeling and optimization of membrane separation using artificial neural network and multi-objective optimization using genetic algorithm. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 91, 883–903 (2013).

Nourbakhsh, H., Emam-Djomeh, Z., Omid, M., Mirsaeedghazi, H. & Moini, S. Prediction of red plum juice permeate flux during membrane processing with ANN optimized using RSM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 102, 1–9 (2014).

Shishegaran, A., Boushehri, A. N. & Ismail, A. F. Gene expression programming for process parameter optimization during ultrafiltration of surfactant wastewater using hydrophilic polyethersulfone membrane. J. Environ. Manage. 264, 110444 (2020).

Corbatón-Báguena, M. J., Álvarez‐Blanco, S. & Vincent‐Vela, M. C. Ultrafiltration of whey: membrane performance and modelling using a combined pore blocking–cake formation model. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 1891–1900 (2018).

Saha, S., Boro, R. & Das, C. Treatment of tea industry wastewater using coagulation-spinning basket membrane ultrafiltration hybrid system. J. Environ. Manage. 244, 180–188 (2019).

Jawad, J., Hawari, A. H. & Zaidi, S. Modeling of forward osmosis process using artificial neural networks (ANN) to predict the permeate flux. Desalination 484, 114427 (2020).

Im, S. J., Viet, N. D. & Jang, A. Real-time monitoring of forward osmosis membrane fouling in wastewater reuse process performed with a deep learning model. Chemosphere 275, 130047 (2021).

Yogarathinam, L. T. et al. Parametric analysis of lignocellulosic ultrafiltration in lab scale cross flow module using pore blocking and artificial neural network model. Chemosphere 286, 131822 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully appreciate the financial support provided by Urmia University (No. 17850-Sep./28/2023). The authors would also like to sincerely thank Mr. Ali Naderi for his valuable assistance in the software section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: Mina Rezapour: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Data curation.Mohsen Esmaiili: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.Mehdi Mahmoudian: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation.Alireza Behrooz Sarand: Review & editing, Modeling evaluation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezapour, M., Esmaiili, M., Mahmoudian, M. et al. Design and modeling of a nanocomposite system for demineralization of sweet whey. Sci Rep 15, 4824 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89009-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89009-w