Abstract

To meet the demands for rapid and environmentally sustainable construction in bridge building, the study of the mechanical properties of manufactured sand concrete (MSC) at early ages is of significant importance. This study aims to investigate the stress–strain curve relationship and construction efficiency of manufactured sand concrete (MSC) at early ages through uniaxial compression tests conducted on 216 specimens at ages of 2 d, 3 d, 4 d, 5 d, 6 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d. The study examined the effects of age, water-cement ratio, and fly ash content on the peak stress and peak strain of MSC. The results indicate that the influence of fly ash content on early-age peak stress is more significant than that of the water-cement ratio. Additionally, the water-cement ratio and fly ash content significantly affect the peak strain of MSC at early ages, particularly within the 2 to 7-day age range. This study evaluates the carbon emissions of MSC as a sustainable building material over its entire lifecycle and concludes that the replacement of supplementary cementitious material (SCM) for cement is essential for emission reduction. Furthermore, a deep neural network (DNN) model with four hidden layers and 100 neurons in each layer was developed based on experimental results. The model was trained to predict the stress–strain curves of MSC under varying water cement ratios, ages, and fly ash content. DNN model was trained and validated through pre-processing and segmenting the original dataset using Pytorch deep learning (DL) libraries. DNN model accurately predicts stress–strain curves that closely align with MSC test curves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, China has experienced rapid growth in its infrastructure development, leading to significant achievements. Concrete, recognized as a crucial synthetic material in the advancement of infrastructure, is extensively employed in the construction of bridges, roads, and buildings1. However, uncontrolled mining activities have resulted in significant ecological harm as a consequence of the extensive use of natural sand, which is one of the component materials2. Furthermore, the existing production of natural sand is inadequate to satisfy the requirements of the construction sector3. When compared to river sand concrete (RSC), manufactured sand concrete (MSC) demonstrates improved workability4and greater compressive strength5,6. Moreover, the mechanical interlocking force between particles of artificial sand exceeds that of river sand particles. As a result, concrete produced with artificial sand exhibits greater strength compared to concrete made with river sand when using the same mix ratio7,8. In specific construction projects with a need for accelerated progress, such as highway bridges, large-volume concrete structures, and municipal road surfaces, the early strength development, early shrinkage, and early creep of MSC are critical mechanical properties that warrant additional investigation. These properties have a direct impact on the performance and construction progress of concrete.

In 2022, the total cement production in China amounted to 2.13 billion tons, indicating a 10.5% decrease compared to the previous year. Over the last ten years, the consumption of cement has consistently surpassed 2 billion tons, with a growing focus on the exploration and utilization of high-performance, high-strength concrete9. The rapid formation of internal microstructure in MSC during the early stages is attributed to its fast hydration reaction, high strength, and short curing period. These characteristics lead to variations in mechanical properties when compared to conventional concrete, consequently impacting the service life and safety of concrete structures10. A comparative analysis was carried out to assess the fundamental performance of C50 concrete utilizing RSC and MSC. The initial compressive strength of MSC was marginally greater than that of RSC, whereas the subsequent strength was slightly lower. However, the disparity was not statistically significant1. The initial elastic modulus and compressive strength of MSC were found to be greater than those of RSC, which are commonly utilized in engineering applications. An approximate linear relationship has been observed between the early-age elastic modulus and compressive strength of concrete11. The compressive strength and other mechanical properties of MSC with a single admixture demonstrated a more rapid increase in growth rate before 7 d compared to after 7 d, indicating a non-linear progression12. Guizhou Province was one of the pioneering regions in China to initiate research on MSC, and it implemented the "Technical Regulations for Mountain Sand Concrete" in 197813. In relation to the mechanical properties of MSC, the prevailing view among scholars is that the strength of MSC surpasses that of RSC14,15. The uniaxial compressive stress–strain curve equation for concrete has been the subject of extensive study by numerous scholars, both domestically and internationally16,17,18,19,20. Damage constitutive models have been developed by varying the strengths of different MSC and utilizing water reducers21. Researchers have developed constitutive models for concrete exposed to marine freeze–thaw cycles22and for spray-applied MSC at various curing ages23. Xie24performed uniaxial compression tests on prismatic specimens of MSC with strength grades of C20, C30, and C40. The results indicated that the stress–strain curves of MSC exhibited a similar trend to those of RSC25. An optimal constitutive model for recycled concrete was established by analyzing load–displacement curves and comparing ultimate bearing capacity through ABAQUS software modeling26. The stress–strain curve of MSC, as modeled by the Sargin model, demonstrates good alignment with the experimental curve27. The study concentrated on the bond strength-slip constitutive model for steel tube pebble manufactured sand recycled coarse aggregate concrete, which incorporated two position functions to consider the variation in anchor depth28.

A range of machine learning (ML) algorithms exists, with many of the more prevalent ones including naive bayes (NB), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), support vector machines (SVM), decision trees (DT), random forests (RF), expectation maximization (EM) algorithms, artificial neural networks (ANNs), and deep learning (DL)29. Numerous scholars have developed models to predict the compressive strength of MSC using ML and ANN30,31. Thilakarathna32 utilized ML algorithms to predict the concrete compressive strength performance, ranking the algorithms in descending order of ANN, GPR, SVM, DT, and LR, with ANN demonstrating the highest performance and Linear Regression the lowest. Tang et al.33 introduced a uniaxial compressive stress–strain model for UHPC materials. Yeh et al.34 employed ANNs to predict the compressive strength of high-performance concrete. The findings indicate that the strength model based on ANNs demonstrates greater accuracy compared to a model relying on regression analysis. Syed et al.35 developed an ANN using Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) algorithm to predict the stress–strain curve, yielding results that closely aligned with experimental data. Liu et al.36 presented an analysis of the tensile behavior of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete (HFRC) using an ANN model. The results obtained from ANN model showed improved curve fitting compared to predictions from models based on mathematical equations. Bui et al.37formulated a predictive framework utilizing an ANN model in conjunction with an enhanced firefly algorithm (MFA). The majority of current stress–strain relationships are derived from the performance criteria established for RSC. Traditional concrete models heavily depend on regression techniques38, and they lack specific theoretical frameworks and computational methods to account for the different properties and response patterns of MSC.

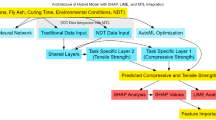

DL is a ML approach that acquires hierarchical feature representations of data by utilizing multiple hidden layers, the application of DL is shown in Fig. 1. The intricate structure of deep neural networks (DNNs) facilitates the autonomous acquisition of increasingly abstract and advanced feature representations from data, thereby enhancing the model’s performance and generalization capacity. Utilizing DNN models to characterize the stress–strain relationships of MSC offers a solution to the constraints associated with the requirement to make assumptions about the mathematical form of traditional concrete models. This presents a more manageable alternative. Furthermore, DNN exhibits significant fault tolerance and robustness39,40.

Recently, research on MSC, both within the country and abroad, predominantly focuses on age periods of 28 d and beyond, particularly within 7 days. Insufficient attention has been given to investigating the mechanical properties of early-age high-strength MSC, and there has been even less research on stress–strain relationships. The research and utilization of manufactured sand typically falls below C50. The accurate understanding of the stress–strain relationship in early-age concrete is a crucial area of research.

Experiments involving uniaxial compression were conducted on high-strength MSC to analyze the failure process at various ages and investigate the variations in characteristic points within the compressive stress–strain curve. These characteristic points include the proportional limit point, peak stress point, inflection point, and their changes are studied in relation to factors such as water-cement ratio, fly ash content, and concrete age. This can provide valuable data accumulation for subsequent studies on MSC. A DNN model comprising four hidden layers, each with 100 neurons, was developed to predict the initial stress–strain behavior of MSC. The DNN model autonomously learns more abstract and higher-level feature representations from the data, offers a shorter timeframe and reduced costs, while also mitigating errors stemming from environmental factors and human operation. This study examines the carbon emissions of supplementary cementitious material (SCM) as a green building material with a full lifecycle. The findings indicate that the use of SCM instead of cement is essential for reducing carbon emissions.

Experimental overview

The premature cracking of concrete is mainly attributed to tensile stresses that surpass the tensile strength of concrete, resulting from volume deformation constraints41. Concurrently, the mechanical properties of concrete at an early age are essential for fulfilling the design and usage criteria of concrete structures during construction, ensuring structural safety, and enhancing construction efficiency42.

This study seeks to examine the patterns of variation in early-age mechanical properties of high-strength MSC under various influencing factors. An experimental analysis is performed to ascertain the compressive strength, elastic modulus, and other pertinent parameters of cubic specimens. Furthermore, the experimental results for compressive strength and the analysis of data from various material mix ratios at early stages are acquired and examined.

Experimental raw materials and mix proportions

Experimental raw materials

The experimental raw materials43 consist mainly of cement, fly ash, coarse aggregates, fine aggregates, manufactured sand, and admixtures. Table 1 presents the raw materials used in the experiment.

Design of mix proportion for MSC

This study diverges from the traditional approach of strength grade labeling and instead concentrates on the exploration of high-strength concrete through the manipulation of water-cement ratio and fly ash content parameters44,45,46. The selected water-cement ratio values were 0.32, 0.34, and 0.36, while the fly ash content was set at 15%, 20%, and 25%. In accordance with the specifications provided in the "Code for Design of Concrete Mix Proportions" (JGJ55-2011), a series of 9 concrete mixtures were formulated and subjected to testing. The precise composition of MSC is detailed in Table 2.

Experimental setup

This study involved 72 test groups, each consisting of 9 specimens. Each test group comprised three replicate specimens, yielding a total of 216 specimens. The tests were conducted at the ages of 2 d, 3 d, 4 d, 5 d, 6 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d. All tests to determine the mechanical properties were carried out following the guidelines outlined in the "Standard Test Methods for Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete" (GB/T 50,081–2002). The compressive strength tests were conducted utilizing HEY-3000 compression testing machine, with data being automatically collected and stored. The static compressive elastic modulus tests and uniaxial compressive stress–strain curve tests were performed utilizing WAW-1000B universal testing machine. Test data was gathered using a dial gauge that was installed on a fixed ring47,48. The equipment49 for both tests is depicted in Figs. 2 and 3.

Analysis of experimental results

Compressive strength of cubes

The compressive strength and elastic modulus of high-strength MSC specimens were determined through experiments conducted at various ages (2 d, 3 d, 4 d, 5 d, 6 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d). The study examined the impact of water-cement ratio and fly ash content on mechanical performance indicators. The failure mode is depicted in Fig. 4, and the results of compressive strength are detailed in Table 3.

The analysis of Fig. 5 reveals that the compressive strength of high-strength mechanism sand concrete demonstrates a nearly linear decreasing trend with an increase in fly ash content. At a consistent water-cement ratio, an increase in fly ash content results in a decrease in compressive strength. At the same age, the compressive strength variation trend decreases with an increase in fly ash content. Under a consistent water-cement ratio, there is a more pronounced variation trend in compressive strength with fly ash content as the age decreases. Significant variation in compressive strength with fly ash content is particularly evident during the 2nd to 4th age range. As the age of the material increases, the fly ash content decreases, while the compressive strength demonstrates a tendency to reach its peak value.

Figure 6 demonstrates that an increase in water-cement ratio results in a nearly linear decrease in the compressive strength of high-strength MSC. At equivalent fly ash content, there is an inverse relationship between the compressive strength and the water-cement ratio. At the same age, the compressive strength variation decreases as the water-cement ratio increases. The compressive strength variation trend with the water-cement ratio becomes more pronounced at a younger age under the same fly ash content. The compressive strength exhibits the most significant variation with the water-cement ratio, particularly at the 2d age. As age progresses, the water-cement ratio decreases, leading to an increase in compressive strength, which tends to approach its peak value.

The analysis presented above indicates a strong correlation between the compressive strength of concrete and the cement content. A sufficient amount of cement can enhance the interfacial adhesion of aggregates, leading to an improvement in the compressive strength of concrete. The intensity of cement hydration reactions during the initial stages is a significant factor contributing to strength enhancement, with lower water-cement ratios resulting in more pronounced hydration reactions. As the concrete ages, there is a tendency for the strength variation to stabilize.

Static compressive elastic modulus

In accordance with the "Standard Test Methods for Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete" (GB/T 50,081–2019), tests were conducted to determine the compressive strength and elastic modulus of high-strength MSC specimens at various intervals (2 d, 3 d, 4 d, 5 d, 6 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d). The study examined the impact of water-cement ratio and fly ash content on the performance indicators. The specific experimental results are presented in Table 4.

The growth rate of the concrete elastic modulus is determined by comparing the elastic modulus at different ages to the elastic modulus at the standard curing age of 28 d. Subsequently, the ratio is denoted as Ec/Ec,28. The association between the elastic modulus and water-cement ratio for each group is depicted in Fig. 7.

In Fig. 7, a discernible negative correlation is evident during the 2–4 d age period between the rate of change of Ec/Ec,28 and the fly ash content as it transitions from 15 to 25%. During the early stages of development, the hydration reactions of cementitious materials play a crucial role in enhancing the strength of concrete. A decrease in fly ash content results in an increase in the amount of cement in the cementitious materials, thereby intensifying the hydration reaction in the concrete. However, a specific quantity of fly ash content can contribute to enhancing the strength of fly ash concrete by filling the micropores between cement and coarse/fine aggregates. During the age period of 5 d to 7 d, the influence of fly ash content on the rate of change of Ec/Ec,28 decreases as the fly ash content gradually increases from 15 to 25%. As the concrete ages, the hydration reaction is completed earlier in this period compared to the 2d to 4d age range, leading to a stabilization in the rate of change in concrete strength. During the extended age range of 14 d to 28 d, an increase in fly ash content from 15 to 25% does not result in a significant difference in the rate of change of Ec/Ec,28 compared to other age ranges.

Figure 8 illustrates a negative correlation between the elastic modulus’s rate of change and the water-to-cement ratio, particularly within the 2-4d day period, as the ratio increases from 0.32 to 0.36. During the early stages of development, the degree of hydration reactions in cementitious materials plays a crucial role in enhancing the strength of concrete, with a reduced water-to-cement ratio resulting in a more significant hydration reaction. During the age period of 5 to 7 days, an increase in the water-to-cement ratio from 0.32 to 0.36 has a diminished effect on the rate of change in the elastic modulus. As concrete ages, the hydration reaction is typically completed, in contrast to the 2–4 day period, and the rate of change in concrete strength tends to stabilize. During the extended age period of 14–28 days, as the water-to-cement ratio rises from 0.32 to 0.36, there is an observed increase in the rate of change in elastic modulus. A smaller water-to-cement ratio results in a higher strength peak, and during the extended age period of 14–28 day period, when the rate of change is slower, the proportion of the strength peak diminishes.

In summary, as the fly ash content increases, the elastic modulus of fly ash concrete initially shows an increasing trend followed by a decreasing trend, but overall it remains negatively correlated with the fly ash content. The data clearly indicates that at a fly ash content of 25%, the rate of change in elastic modulus is most significant between the 2–4 day periods. This suggests that an excessive fly ash content has a detrimental effect on the concrete strength during the 2 day period.

Peak stress and peak strain values

Peak stress value

The strain at the peak stress point is referred to as the peak strain, while the strain at 85% of the peak stress in the descending section of the compressive stress–strain curve is termed the ultimate strain. The peak stress, peak strain, and ultimate strain values for C50 concrete are presented in Table 5.

The performance of early-age specimens within 7 d is of greater interest when compared to those at 14 d to 28 d. As depicted in Fig. 9, the correlation between peak stress and age demonstrates a pattern of initial growth followed by a decline with increasing age. Upon analyzing the aforementioned groups, for a consistent fly ash content, the peak stress at different ages rises as the water-cement ratio decreases. Experimental findings indicate that an increase in peak stress results in a corresponding increase in the brittleness of concrete. Following a 7d curing period, concrete specimens exhibit a tendency to develop cracks when subjected to higher stresses, and these cracks propagate rapidly, ultimately resulting in sudden failure. A reduction in the water-cement ratio, resulting in an increased amount of cementitious material utilized, has a positive impact on enhancing the strength of concrete.

The data indicates that the effect of the water-cement ratio on the peak stress of concrete aligns with its influence on compressive strength. Similarly, the peak stress is inversely related to the water-cement ratio, indicating that a lower water-cement ratio results in higher peak stress as shown in Fig. 9.

Peak strain value

The peak strain ξcis affected by various factors, including the concrete’s strength, the rate of test loading, the specimen size, the method of constraint, and the inherent variability of the concrete material. For unconfined concrete subjected to uniaxial load, the maximum strain is predominantly influenced by the concrete strength, which is associated with the water-cement ratio, age, fly ash content, and other factors to different extents50. The peak strain values of high-strength MSC are displayed in Table 6, while the correlation with age is depicted in Fig. 10.

In Fig. 10, the age of concrete exerts a discernible influence on the peak strain during uniaxial compression. In general, there exists a negative correlation between the peak strain of concrete and its age. As the duration of aging increases, the formation and hardening reactions of cement gel gradually reach completion, leading to a progressive increase in the strength of the concrete.

Uniaxial compressive stress–strain curve of concrete

The stress–strain test curves for uniaxial compression at ages of 2 d, 3 d, 4 d, 5 d, 6 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d are depicted in Fig. 11 and 12. As depicted in the figures, the stress–strain curve of C50 MSC becomes progressively steeper with advancing age, suggesting an increase in the peak stress of the concrete, a decrease in the peak strain, and an overall increase in brittleness. This trend aligns with the typical progression of strength and deformation in traditional concrete.

Development and prediction of DNN models

DNNs are a type of ML model that is built on ANNs, distinguished by their multi-layered structure with hidden layers. DNN constitute the fundamental basis of DL, a ML approach aimed at acquiring hierarchical feature representations of data by utilizing multiple layers of hidden units. The depth of DNNs facilitates the automatic acquisition of abstract and higher-level feature representations from data, thereby improving the model’s performance and generalization capabilities. DNNs have made significant advancements in various fields, including image recognition, speech recognition, natural language processing, recommendation systems, and machine translation. DNNs have the ability to perform hierarchical feature extraction and representation learning, enabling them to effectively manage complex nonlinear relationships and large-scale datasets. This capability leads to enhanced accuracy and efficiency of models.

To date, there has been no DNN prediction of the stress–strain behavior of high-strength mechanism sand concrete materials, particularly regarding the mechanical performance at early ages. When compared to conventional experimental methods, the utilization of DNN models for predicting the constitutive models of MSC offers advantages such as reduced time and cost, as well as avoidance of errors stemming from environmental factors and manual operation. Consequently, this approach provides enhanced controllability. Furthermore, DNNs exhibit significant fault tolerance and robustness51.

DNN model and data processing

A DNN is comprised of numerous neural network layers, encompassing an input layer, multiple hidden layers, and an output layer. Each stratum consists of numerous neurons, and information is conveyed between them via connection weights. The depth of the network is determined by the number of hidden layers, whereas the width of each hidden layer is determined by the number of neurons within it. The architectural overview of DNN and simple neural network is shown in Fig. 13.

Activation functions play a crucial role in DNNs as they are nonlinear functions that introduce nonlinearity to enhance the network’s expressive capacity. The common activation functions encompass Sigmoid, rectified linear unit (ReLU), and Tanh functions. The selection of an activation function has a substantial impact on the performance of a network and its training effectiveness52.

The ReLU function eliminates complex calculations and increases the speed of operations and converges faster than Tanh and Sigmoid.

LeakyReLU can be considered as a solution to the ReLU neuron death problem. LeakyReLU outputs small values of negative input.

The Sigmoid function is continuously derivable and can be used directly to optimize the network parameters using the gradient descent algorithm.

The Tanh function is very similar to sigmoid, except that the output value is in the range of −1 to + 1.

The Softmax function is commonly used for multi-class classification tasks and applied to output neurons.

To predict the stress–strain correlation of high-performance concrete through DNN model, the raw dataset will encompass extensive data pertaining to the stress–strain relationship of high-performance concrete. The proposed DNN model utilizes three parameters as input data: the water-cement ratio, fly ash content, and age of the concrete. Consequently, the output data consist of the stress, strain, and compressive strength.

Subsequently, MSC experimental dataset is partitioned into three sets: training, validation, and testing datasets. These sets are utilized for the purposes of training, evaluating, and testing DNN model, respectively. The raw data undergoes shuffling and is subsequently partitioned into training, validation, and testing datasets.

The following equation is utilized for preprocessing the raw dataset by standardizing the original sample strain, stress, and aging data sets, resulting in similarly standardized output data. Normalizing the dataset can help prevent overlaps of data with different magnitudes and premature saturation of hidden layer nodes53.

where xi, wj, wmin, and wmax are the normalized value, actual value, minimum, and maximum of the data samples of test.

Training and validation of DNN model

The inclusion of weights and biases is essential for the process of fitting and prediction in neural networks. The training process of DNN model focuses on the adjustment of network weights and biases to minimize the specified loss function as shown in Fig. 1454. This process entails conducting forward and backward computations layer by layer. In the model learning algorithm, the bias values and weights are updated after each presentation of the entire pattern set to the network. The advanced Pytorch55DL library is utilized for training DNN model, which is composed of four hidden layers, each containing 100 neurons. The optimizer selected for this task is batch gradient descent (BGD).

This article has chosen ReLU function as the activation function due to its simple and efficient computational properties, as well as its sparsity of activation. It has been extensively utilized in DNNs and has shown strong performance in a variety of tasks. The computation involves only the determination of the maximum value and comparison operations, without the requirement for complex mathematical calculations. Additionally, ReLU function is capable of mitigating the vanishing gradient issue during training by maintaining a constant gradient of 1 for input values greater than 0. This characteristic is advantageous for gradient propagation and model training.

The result obtained from using ReLU activation function as a nonlinear transformation in neural networks is expressed as follows:

ReLU function is a piecewise linear function that produces the input value for non-negative input values and 0 for negative input values. This nonlinearity enables ReLU function to introduce non-linear transformations, thereby enhancing the expressive capacity of the neural network. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential issue of “dead neurons” associated with ReLU function, which can be alleviated by utilizing enhanced variations of ReLU.

The study utilizes root mean square error (RMSE) as the loss function for assessing the error of the neural network’s output data, and employs the coefficient of determination R2 to assess the predictive capacity of the neural network model. The RMSE and the coefficient of determination (R2) are computed using Eq. (3) and (4) correspondingly. RMSE values nearing 0 and R2values nearing 1 suggest a strong fit of DNN model’s predictive data to the original data and improved predictive performance of DNN model. A learning rate of 0.01 is initially established. The decrease in loss occurs gradually as the learning rate decreases and DNN model converges further52.

where \({\mathbf{y}}_{\mathbf{i}}^{\mathbf{k}},\overline{\mathbf{y },}{\widehat{y}}_{\text{i}}\) are the true, average, and predicted values, respectively.

Stress–strain curve prediction model

The data of the test dataset is fed into the trained DNN model, enabling the prediction of stress–strain curves of MSC under varying water cement ratios, ages, and fly ash content. The stress–strain curve of MSC at early ages is compared with the stress–strain curve predicted by the DNN model, as shown in Fig. 15.DNN model proposed in this article exhibited high accuracy in predicting the stress–strain behavior of MSC at early ages52.

Carbon emission of MSC

The carbon emissions associated with the constituent materials of MSC encompass both direct and indirect GHG emissions incurred during the extraction, transportation, and production of concrete mix components56. Simapro9.4 software is utilized to calculate carbon emissions based on international data, employing Ecoinvent3.0 database.

Simapro9.4 does not contain data on carbon emissions from manufactured sand. This study utilized the carbon emission data from Dou57. The process of producing manufactured sand involves the preparation of block material, decomposition, feeding, crushing, sieving, stacking, and removal of waste residue according to the standard quota. The basic data for manufactured sand is determined based on the collection and processing of reference quota materials, with the unit of manufactured sand being 100 m3. The lifecycle inventory of 1 kg of manufactured sand includes diesel oil, electricity, non-metallic resources, and other factors, as presented in Table 7.

The embodied carbon of materials in concrete mix encompasses both direct and indirect greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions arising from the extraction of raw materials, as well as the transportation and manufacturing processes involved in producing materials for concrete mix. The embodied carbon of materials is defined as the total emissions associated with the production of goods and services, both direct and indirect, as represented in Eq. (5).

where GHGdirect,k is direct GHG emissions due to manufacturing process of material k (e.g., clinker, sand, and fly ash); while GHGdirect is GHG emissions due to manufacturing process of intermediate product i for product k and its transportation of intermediate product i to the manufacturing site. The direct (GHGdirect,k) and indirect GHG (GHGindirect) emissions can also be determined as the sum of GHG emissions from manufacturing process of material kGHGprocess,k), intermediate product i to manufacture of material k(GHGi) and the transportation of material i required per unit of the material k(GHGtransport,i). Table 8 shows the embodied carbon values of different mix proportions of MSC (kgCO2eq/m3).

The contributions of each constituent to the total embodied carbon value of the mix are presented in Table 8. Cement is the primary material that significantly impacts carbon emissions. The higher binder ratio and cement content in concrete mixes, along with the significant emissions generated by the cement calcination process58, underscore the importance of utilizing SCM to replace cement to mitigate emissions.

Conclusions

This study aims to examine the stress–strain characteristics of high-strength MSC in the initial stages of bridge construction. The research conducts experiments to analyze the impact of water-cement ratio, fly ash content, and age on compressive strength, elastic modulus, and critical points of the stress–strain curve. Additionally, a DNN model is developed to depict the stress–strain behavior of high-strength concrete during the early-age phase. The conclusions can be derived as follows:

-

(1) The failure process of MSC can be categorized into four distinct stages: the linear elastic stage, internal crack propagation stage, visible crack development stage, and residual strength stage. Various factors, including water-cement ratios, fly ash contents, and the age of the material, can affect both the failure process and the resulting failure morphology. The brittle failure is most pronounced when the water-cement ratio is 0.32 and the fly ash content is 15%.

-

(2) As concrete cures, the increase in peak stress can be categorized into two distinct phases. The initial phase, which occurs between 2 and 7 days, is characterized by an average increase in peak stress of 20 MPa. The subsequent phase, extending from 7 to 28 days, exhibits a reduced average increment of 8 MPa.

-

(3) The reduction of the water-cement ratio has been demonstrated to significantly enhance both the peak stress and peak strain of concrete, while also highlighting the brittle behavior in the descending segment of the stress–strain curve. In contrast, fly ash may influence the development of strength at early ages.

-

(4) The DNN model developed in this study demonstrates exceptional stability, rapid computational speed, high accuracy, and robust nonlinear fitting capabilities across multiple factors. Furthermore, it exhibits strong generalization and scalability. Once trained and validated, the DNN model is capable of accurately predicting the stress–strain behavior of high-strength MSC, surpassing the performance of existing mathematical models.

-

(5) Cement is the primary material that significantly impacts carbon emissions. The use of SCM to substitute cement is crucial for emission reduction.

Data availability

The experiments in the paper involve the study of early-age mechanism of sand concrete conducted in collaboration with the team led by Pu Guangning from Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology and Longchuanjiang River Extra-large Bridge on a certain high-speed highway project in Chongqing, China. Due to the requirements of the highway construction authority, the data is not publicly.But are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References:

Xie, Y. D. et al. Effect of fine aggregate type on early-age performance cracking analysis and engineering applications of C50 concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 323, 126633 (2022).

Cheng, C. Study on the Effect of Lithology and Gradation of Manufactured Sand on Concrete Performance[D], Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 2019.

Zhang, J., Dong, L. & Wang, Y. Toward intelligent construction: Prediction of mechanical properties of manufactured-sand concrete using tree-based models. J. Clean. Prod. 258, 120665 (2020).

Bonavetti, V. L. & Irassar, E. F. The effect of stone dust content in sand. Cem. Concr. Res. 24(3), 580–590 (1994).

Ding, X., Li, C., Xu, Y., Li, F. & Zhao, S. Experimental study on long-term compressive strength of concrete with manufactured sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 108, 67–73 (2016).

Li, F. L., Zeng, Y. & Li, C. Y. Evaluation of relations among basic mechanical properties of concrete with machine-made sand. Adv. Mater. Res. 418–420, 473–476 (2012).

Shen, W. et al. Characterization of manufactured sand: particle shape, surface texture and behavior in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 114(1), 595–601 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Coupled effects of the content and methylene blue value (MBV) of microfines on the performance of manufactured sand concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 240(20), 117953 (2020).

J.Y.Tao,Resistance of Early-age Cement PastesStudy on Hydration,Autogenous Shrinkage and Freeze-thaw[D],Huazhong University of Science and Technolog,2021

Z.F.Zhao, H.F.Li, Q.Y.Tan,etc, Review on testing method of cracking resistance performance of concrete at early age, Laboratory Science,2012,15(06),44–47.

Xu, C. C. & An, J. J. Experimental study on early ages compressive strength and elasticity modulus of manufactured sand concrete with different replacement ratios. Shan Dong Ke Ji 06, 54–56 (2016).

Xu, Z. Q., Yuan, Q., Yang, Z. K., Wang, M. M. & Wang, D. Y. Mechanical property experiment and uniaxial constructive model for concrete at early age. J. Shenyang University of Technology 37(01), 92–96 (2015).

Architectural Science Research Institute of the Fourth Bureau of the National Construction Commission,Mountain sand concrete[M],Beijing:China Architecture & Building Press,1979.

Bonavetti, V.L., Donza, H. Rahhal, V.F., et al. High strength concrete with limestone filler cements, In:V.M. Malhotra, P. Helene, L.R. Prudencio, D.C.C.DaI Molin (Eds), High-Performance Concrete and Performance and Quality of Concrete Structures, 567~580 (ACISP-186, American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hill, MI, 1999).

Prakash Rao, D.S., Giridhar Kumar. Investigations on Concrete with Stone Crushed Dust as Fine Aggregate, The Indian Concrete Journal.45–50 2004.

Jian, C. Lim, Togay Ozbakkaloglu, Stress-strain model for normal- and lightweight concretes under uniaxial and triaxial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 71, 492–509 (2014).

Zheng, W. Z., Li, H. Y. & Wang, Y. Compressive stress-strain relationship of steel fiber-reinforced reactive powder concrete after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 931–940 (2012).

Xu, M., Wang, T. & Chen, Z. F. Experimental research on uniaxial compressive stress-strain relationship of recycled concrete after high temperature. J. Build. Struct 36(2), 158–164 (2015) ((in Chinese)).

Da, B. et al. Experimental research on whole stress-strain curves of coral aggregate seawater concrete under uniaxial compression. J. Build. Struct. 38, 151 (2017) ((in Chinese)).

Xu, L. H. et al. Study on uniaxial tensile stress-strain relationship of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. China Civil Eng. J. 7, 35–45 (2014) ((in Chinese)).

Han, Z. et al. Study on axial compressive behavior and damage constitutive model of manufactured sand concrete based on fluidity optimization. Constr. Build. Mat. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128176 (2022).

Qiu.W.L, Teng.F, Pan.S.S,. Damage constitutive model of concrete under repeated load after seawater freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mat. 236(5), 117560 (2020).

Li.Q, Wang.X, Zou.Z,et al.Dynamic Behaviour of Manufactured Sand Shotcrete at Early Age, Social Science Electronic Publishing. 2023.

Xie, K. Z., Liu, Z. W. & Gai, B. Z. Stress-Strain Test of Manufactured Sand Concrete. Bulletin Chin. Ceram. Soc. 39(12), 3823–3831 (2020).

Chen, Y.B. Analysis and research on the factors affecting the elastic modulus of C50 concrete used in Yunnan Highway[D], Yunnan University,2016.

Li, J. Q., Chen, Z. H. & Du, Y. S. Study on constitutive model of core concrete of recycled aggregate concrete filled steel tubular columns under compression. Industrial Constr. 51(05), 108–115 (2021).

Xie, K. Z., Liu, Z. W. & Gai, B. Z. Constitutive relationship and mechanical properties of mechanism sand concrete with different rock types. J. Archit. Civil Eng. 38(01), 99–106 (2021).

Sha, M., Li, X. & Liu, Z. Y. Bond-slip constitutive model of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with limestone manufactured sand in square steel tubes. J. Archit. Civil Eng. 40(01), 38–48 (2023).

Mi, X., Tang, T. & Zhu, Y. C. Progress of Machine Learning in Material Science Materials Reports. Mat. Rev. 35(15), 15115–15124 (2021).

Yu, L.H. Manufactured Sand Mix Ratio Design and Eco-efficiency Evaluation of LCA-LCC Based on Machine Learning[D], Beijing Jiaotong University,2022.

Zhao, Y. et al. Predicting compressive strength of manufactured-sand concrete using conventional and metaheuristic-tuned artificial neural network. Measurement. 194, 110993 (2022).

Thilakarathna, P. S. M. et al. Embodied carbon analysis and benchmarking emissions of high and ultra-high strength concrete using machine learning algorithms. J. Clean. Produc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121281 (2020).

Tang, J. et al. Uniaxial compression performance and stress–strain constitutive model of the aluminate cement-based UHPC after high temperature. Constr. Build. Mat. 309, 125–173 (2021).

Yeh, I.-C. Modeling of strength of high-performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Cem. Concr. Res. 28(12), 1797–1808 (1998).

Zaidi, S. K., Ayaz, A. M. & Sharma, U. K. Unified model using artificial neural network for high strength fibrous concrete subjected to elevated temperature. Innovative Infrastruct. Solut. 7(1), 87 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. An artificial neural network model on tensile behavior of hybrid steel-PVA fiber reinforced concrete containing fly ash and slag power. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 14, 1299–1315 (2020).

Bui, D.-K. et al. A modified firefly algorithm-artificial neural network expert system for predicting compressive and tensile strength of high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mat. 180, 320–333 (2018).

Lee, S.-C. Prediction of concrete strength using artificial neural networks. Eng. Struct. 25(7), 849–857 (2003).

Hinton, G. E. & Salakhutdinov, R. R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science. 313(5786), 504–507 (2006).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature. 521(7553), 436–444 (2015).

Ni, T.Y. Tensile creep characteristics and its evaluation of high strength concrete containing mineral admixtures at early ages[D],Zhejiang University of Technology,2021.

Xu, G. Q., Liu, L. Y. & Hei, Z. T. Current research status on the mechanical properties of early-age. Sichuan Cement 04, 322–323 (2018).

Ning, C.J. A Study of Key Technology of High Performance Concrete sand[D]. Guangzhou University.2017.

Grasley, Z. & El-Helou, R. D Ambrosia M, et al, Model of infinitesimal nonlinear elastic response of concrete subjected to uniaxial compression. J. Eng. Mec. 141(7), 04015008 (2015).

Sima, J. F., Roca, P. & Molins, C. Cyclic constitutive model for concrete. Eng. Struct. 30(3), 695–706 (2008).

Breccolotti, M. & Bonfigli, M. F. D Alessandro A, et al, Constitutive modeling of plain concrete subjected to cyclic uniaxial compressive loading. Constr. Build. Mat. 94, 172–180 (2015).

Demin, W. & Fukang, H. Investigation for plastic damage constitutive models of the concrete material. Proced. Eng. 210, 71–78 (2017).

Gokulnath, C., Varaprasad, D. & Saravanan, U. A three dimensional constitutive model for plain cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mat.s 203, 456–468 (2019).

Guo, Q. Zhang, Z. Pu, G.M. etc, Experimental study on the time-dependent relationship between compressive strength and elastic modulus and constitutive model of earlyage manufactured sand concrete, Highway Engineering,2023.

Li, M.W. Study on mechanical properties of high-strength composite limestone powder-silicafume-machine-made mixed sand concrete and small eccentric compression column [D], China University of Mining and Technology, 2022.

Liu, Z. et al. A low-carbon road map for china. Nature 500(7461), 143–145 (2013).

Xu, L., Yang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Xue, Y. Estimation of stress–strain constitutive model for ultra-high performance concrete after high temperature with an deep neural network based method. Constr. Build. Mat. 408, 133690 (2023).

Xue, J., Shao, J. F. & Burlion, N. Estimation of constituent properties of concrete materials with an artificial neural network based method. Cem. Concr. Res. 150, 106614 (2021).

Abellan, G. J., Fernandez, G. J. & Torres, C. N. Properties prediction of environmentally friendly ultra-high-performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Europ. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 26(6), 2319–2343 (2022).

Paszke, A. et al, “Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library”, Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

Thilakarathna, P. S. M., Seo, S. & Baduge, K. K. Embodied carbon analysis and benchmarking emissions of high and ultra-high strength concrete using machine learning algorithms. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 121281 (2020).

K.J.Dou,Study on Evaluation of Human Health Damage in Road Engineering Based on Life Cycle Assessment[M],Zhongyuan University of Technology, (2018).

Latawiec, R. et al. Sustainable concrete performancedCO2-emission. Environ. Times 5(2), 27 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The support from Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2022JQ-560) is greatly appreciated.

Funding

Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi,2022JQ-560,2022JQ-560,2022JQ-560,2022JQ-560

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.; methodology, Q.G.; . and L.H.; investigation, B.L., writing—original draft, L.H.; writing—review and editing,L.H.,software, D.S.,codes, L.H.and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, L., Pu, G., Guo, Q. et al. Deep neural network-enhanced prediction and carbon footprint analysis of early-age high-performance manufactured sand concrete’s stress–strain behavior. Sci Rep 15, 12947 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89016-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89016-x