Abstract

Smoking may be associated with an increased risk of lung metastasis in cancers of non-lung origin. We leverage survey and electronic health record data from the diverse All of Us Research Program (AoURP) database to investigate whether smoking and smoking-related behaviors increase the risk of lung metastasis in non-lung primary cancers. The results suggest that cigarette use, measured by four continuous variables, does not increase the risk of lung metastasis in seven common cancer types but demonstrates a small significant effect in a cohort including all types of cancer in the database in both univariable and multivariable analyses. An increased odds ratio of electronic smoke use in patients with lung metastasis was seen in multivariable analyses of the all cancer (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.04–1.59, P = 0.02) and liver cancer (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.06–2.28, P = 0.02) groups. After adjusting for estimated cigarette pack years in the multivariable model, the result remained significant for liver cancer (OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.02–2.47, P = 0.04) but not the all cancer cohort. These results warrant further inquiry and suggest that smoking and e-cigarettes may be associated with lung metastasis risk in patients with non-lung tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the U.S., responsible for 600,000 deaths in 20201. One of the primary drivers of cancer mortality is metastasis, which can lead to the disruption in the function of organs and organ systems. The metastasis of cancers of non-lung origin to the lung has been well described, and it is thought that organ-specific metastasis relies on a pre-metastatic niche (PMN) in the target secondary organ2. The formation of a lung PMN is a complex process that results from immune cells in the surrounding microenvironment and crosstalk between the primary tumor and metastatic cells, among other involved components2.

Studies have demonstrated that smoking may be associated with an increased risk of lung metastasis in cancers of non-lung origin. For example, in breast cancer, evidence suggests that a nicotine-promoted proinflammatory microenvironment may play an important role in metastasis3,4,5. Specifically, chronic nicotine exposure recruits pro-tumor N2-neutrophils, which induce the mesenchymal-epithelial transition and facilitate tumor colonization and metastasis5. In pancreatic cancer, smoking has been shown to promote metastasis into the liver and lung6. In colorectal cancer, multivariate analysis demonstrates that being a current smoker was an independent risk factor for pulmonary metastases7. In addition to the role of cigarette smoking, e-cigarettes, which have dramatically increased in popularity in recent years8, have been shown to promote breast carcinoma progression and lung metastasis9. While the effect of e-cigarettes on lung metastasis is understudied, another paper suggests that non-nicotine e-cigarettes may promote liver fibrosis, suggesting that e-cigarettes may alter underlying tissue integrity10,11. These results suggest that a large-scale characterization of smoking-related behavior on lung metastasis across common cancer types may provide insights that help guide future prospective studies and experimental inquiry that may ultimately influence clinical screening and treatment decisions. We hypothesize that smoking and smoking-related behaviors may play a role in the establishment of the lung PMN and metastasis of tumors of non-lung origin to the lung. In the present study, we utilize data from the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us Research Program (AoURP) and perform univariable and multivariable analyses to characterize the association between smoking and smoking-related behaviors and lung metastasis.

Methods

The AoURP is a prospective cohort study with the objective of recruiting > 1 million US individuals to provide a comprehensive database for researchers interested in questions related to participant lifestyle, access to care, environment, and genomics12. Data in the AoURP is collected through self-reported surveys, physical wearables, and electronic health records (EHR). Using the cohort builder function within the All of Us workbench, we created each case-specific cohort for patients with breast, liver, colorectal, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, and renal cancer, respectively, in addition to a case cohort of patients with all cancer types in the database and lung metastasis. The all cancer group includes the seven previously mentioned common cancer types, in addition to all other listed cancers in the database, except primary lung cancer. All cancer-related diagnoses for the case cohorts were extracted from EHR data, while analysis of smoking-related behaviors was obtained from survey data that were collected at the time of study enrollment.

We analyzed the relationship between various smoking-related variables and lung metastasis in breast, liver, colorectal, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, and renal cancer using data from participants with these and other cancer types from the AoURP. We first investigated quantitative survey parameters, including the number of years smoked, the current number of cigarettes smoked per day, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the estimated cigarette pack years across the seven cancer types, followed by an analysis of binary survey outcomes related to cigarette and smoking-related behaviors. We also performed our analyses in the all cancer cohort, which included all other listed cancers in the database, except primary lung cancer in order to control for overestimation of risk that might be associated with lung cancer recurrences after primary lung cancer. Significance was established for all analyses using logistic regression, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression models were adjusted for age, sex, income, and insurance status (sex not included for ovarian and prostate cancer analyses). Participants who listed “Not male, not female, prefer not to answer, or skipped” or “No matching concept” for sex at birth and “Don’t Know/Prefer Not To Answer/Skip” for insurance or income were excluded from the multivariable analysis. The estimated cigarette pack years were calculated by multiplying a number of years smoking in the past by the average number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by twenty.

Informed participant consent was obtained by the AoURP, with all participants consenting to participate, viewing information about the AoURP goals, and what participation entails, and full details on the consent process are available through the AoURP at this link: https://allofus.nih.gov/about/protocol/all-us-consent-process. Analytic methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, in addition to adhering to AoURP policies. No experimental protocols were included in this study and additional ethical approval was not required as the data utilized in this study was de-identified.

Results

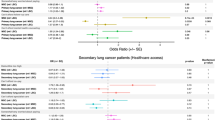

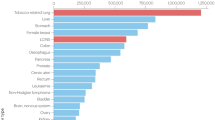

The patient demographic data and EHR Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes are shown in Table 1. The highest rate of lung metastasis was observed in liver cancer (21.9%) followed by pancreatic (9.7%) and renal (9.7%) cancers. The lowest rate of lung metastasis was observed in prostate cancer (1.9%), followed by breast cancer (2.8%). Univariable and multivariable analyses of the number of years smoked, the current number of cigarettes smoked per day, the average number of cigarettes per day, and the estimated cigarette pack years demonstrated no statistically significant differences between patients with and without lung cancer metastasis in the seven studied cancer types, except for a significant weakly negative effect (P = 0.01) of number of years smoked on liver cancer metastasis to the lung in the univariable analysis (Table 2). In the all cancer case group, however, a significant weakly positive effect was observed for all four variables.

Analysis of binary smoking-related variables was performed next (Table 3). In the univariable analysis, an increased odds ratio of electronic smoke use in patients with lung metastasis was seen in the all cancer (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.12–1.68, P < 0.01) and liver cancer (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.12–2.32, P < 0.01) case groups with metastasis to the lung. Multivariable analyses demonstrated similar effects for both all cancer (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.04–1.59, P = 0.02) and liver cancer (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.06–2.28, P = 0.02) case groups. An increased odds ratio of cigar smoked participation (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.06–2.08, P = 0.02) was observed in univariable analysis for colorectal cancer with metastasis. An increased odds of smoking frequency was also observed in both all cancer (OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.10–1.63, P < 0.01) and prostate cancer (OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.02–3.75, P = 0.03) case groups.

Multivariable analyses modeling electronic smoke use in patients with lung metastasis was repeated including an adjustment for the number of years smoked in the past or estimated cigarette pack years (Table 4). An increased odds of electronic smoke use in patients with liver cancer and lung metastasis was observed upon adjustment for the number of years smoked in the past (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.14–2.75, P = 0.01) and the estimated cigarette pack years (OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.02–2.47, P = 0.04) but not for the all cancer group. The Spearman correlation between “some or every day” current smoking with e-cigarette use was higher in the all cancer group (ρ = 0.34) compared to liver cancer (ρ = 0.27) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examines lung metastasis and smoking-related behavior in the AoURP and across a wide range of cancers. The all cancer case group results suggest that the number of years smoked, the current number of cigarettes smoked per day, the average number of cigarettes smoked, and estimated cigarette pack years have a weakly positive effect on lung metastasis. Additionally, in a multivariable model, electronic smoke use is associated with a higher odds ratio of lung metastasis in the all cancer and liver cancer case groups, which remains significant in liver cancer after adjustment for previous smoking history. This may be due to the higher correlation between current smoking and e-cigarette use in the all cancer case group compared to the liver cancer group. These results warrant further inquiry and suggest that both smoking and e-cigarettes may be associated with lung metastasis risk. These results may be explained by several possibilities. One possibility is that one or more chemical compounds in cigarettes and electronic cigarettes promote cancer metastasis and another is that participants who smoke cigarettes and develop cancer might switch to electronic cigarettes. The first possibility concurs with previously published findings in cellular models suggesting that e-cigarette use may promote lung metastasis9. The second possibility warrants further study. In the current dataset, we do not have temporal data about smoking or e-cigarette behavior over time, so future large cohort studies are needed to further evaluate this possibility.

Additional factors that may affect the electronic cigarette results include quantity, time, and type of e-cigarette used. Future prospective studies or detailed retrospective studies are needed to validate the results from this study and better characterize the effect of smoking and smoking-related behaviors on metastasis of non-lung cancers to the lung. Furthermore, wet lab studies are needed to better understand how cigarette and e-cigarette use may contribute to a lung PMN. To our knowledge, however, this is the first study characterizing the effect of smoking and smoking-related behaviors on lung metastasis in non-lung primary cancers.

The present study has several limitations, including variability in EHR data quality13, a limited sample size, lack of information on cancer stage, and the absence of a self-reported pack-year metric14 in the survey data for smoking behavior analysis, although an approximated pack-year metric was utilized as described in the methods. The variability in data quality was highlighted by the presence of a very small proportion of males assigned at birth with ovarian cancer and females assigned at birth with prostate cancer, suggesting imperfections in the data quality. Additionally, survey data may be subject to biases and subjectivity, and future work should validate the current study as new versions of the data are released and/or in an independent dataset. Taken together, the results from this study suggest that further research should be done to uncover the potential roles of cigarettes, nicotine, and electronic cigarette use in patients with cancer diagnoses, which may help guide future clinical management.

Data availability

The following data availability statement is included in the manuscript: “Data from this program are accessible at www.allofus.nih.gov, and this study was conducted on version 7 of the registered tier data utilizing the All of Us Researcher Workbench.”

References

Schwartz, S. M. Epidemiology of cancer. Clin. Chem. 70(1), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvad202 (2024).

Cucanic, O., Farnsworth, R. H. & Stacker, S. A. The cellular and molecular mediators of metastasis to the lung. Growth Factors 40(3–4), 119–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/08977194.2022.2087520 (2022).

Wu, M., Liang, Y. & Zhang, X. Changes in pulmonary microenvironment aids lung metastasis of breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 58. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.860932 (2022).

Murin, S. & Inciardi, J. Cigarette smoking and the risk of pulmonary metastasis from breast cancer. Chest 119(6), 1635–1640. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.119.6.1635 (2001).

Tyagi, A. et al. Nicotine promotes breast cancer metastasis by stimulating N2 neutrophils and generating pre-metastatic niche in lung. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20733-9 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. HDAC4 mediates smoking-induced pancreatic cancer metastasis. Pancreas 51(2), 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000001998 (2022).

Yahagi, M. et al. Smoking is a risk factor for pulmonary metastasis in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 19(9), O322–O328. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13833 (2017).

Smith, M. L., Gotway, M. B., Crotty Alexander, L. E. & Hariri, L. P. Vaping-related lung injury. Virchows Arch. 478(1), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02943-0 (2021).

Pham, K. et al. E-cigarette promotes breast carcinoma progression and lung metastasis: macrophage-tumor cells crosstalk and the role of CCL5 and VCAM-1. Cancer Lett. 491, 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2020.08.010 (2020).

Crotty Alexander, L. E. et al. Chronic inhalation of e-cigarette vapor containing nicotine disrupts airway barrier function and induces systemic inflammation and multiorgan fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 314(6), R834–R847. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00270.2017 (2018).

Li, X., Yuan, L. & Wang, F. Health outcomes of electronic cigarettes. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 137(16), 1903–1911. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000003098 (2024).

Alonso, A. et al. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the all of Us Research Program. PLoS One. 17(3), e0265498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265498 (2022).

Engel, N. et al. EHR data quality assessment tools and issue reporting workflows for the “All of Us” research program clinical data research network. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl Sci. Proc. 2022, 186–195 (2022).

US Preventive Services Task Force et al. Screening for lung cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 325(10), 962–970. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1117 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276. In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants. V.S. would like to thank the Baylor College of Medicine Medical Scientist M.D./Ph.D. training program for their support.

Funding

Our study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for U19CA203654, R01CA243483, and R03CA277197. C.I.A. is a Research Scholar of the Cancer Prevention Research Interest of Texas (CPRIT) award (RR170048).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: V.S., J.B., and C.A. Data curation, formal analysis, and visualization: V.S. Writing - original draft: V.S. Writing - reviewing and editing: V.S., J.B., Y.H., and C.A. Supervision - C.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, V.R., Byun, J., Han, Y. et al. Effects of smoking behavior on lung metastasis in the All of Us Research Program. Sci Rep 15, 11114 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89209-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89209-4