Abstract

The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is emerging as a promising marker for insulin resistance and serves as an independent risk predictor for cardiovascular outcomes. The coronary angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance (AMR) is computed to evaluate coronary microcirculation. However, the association between the TyG index and the AMR in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains unclear. We consecutively recruited 168 patients with T2DM and STEMI who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) at Taizhou People’s Hospital from January 2022 to December 2023. Patients were classified into low AMR group (AMR < 2.5) and high AMR group (AMR ≥ 2.5). The TyG index was calculated using the formula: ln [plasma triglyceride (mg/dL) × fasting blood glucose (mg/dL)/2]. The study enrolled 81 patients in the low AMR group and 87 in the high AMR group, with the TyG index being significantly higher in the high AMR group. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association between the TyG index and high AMR after adjusting for confounding variables (odds ratio: 2.449, 95% confidence interval: 1.421–4.220, and p = 0.001). The area under the curve for the TyG index predicting high AMR was 0.650 (95% confidence interval: 0.57–0.73, p < 0.001), with a cut-off value of 9.57. Our findings indicate that the TyG index is significantly associated with AMR in T2DM patients with STEMI undergoing pPCI, suggesting it may serve as a valuable predictor of high AMR in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) with stent implantation has become the paradigm treatment of acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)1,2. The contribution of pPCI in treating STEMI is significantly compromised by impaired coronary microcirculation flow, which is associated with adverse clinical outcomes3,4,5. While contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is the gold standard for assessing coronary microcirculation6,7, its use is often limited in clinical practice due to costs and constraints related to critically ill patients. In this context, the angiographic microvascular resistance index (AMR), derived from a single-view, pressure-wire- and adenosine-free approach, provides a non-invasive alternative for evaluating microcirculatory function directly within the catheterization laboratory and has demonstrated prognostic value in STEMI patients4.

Insulin resistance has been verified to be associated with impaired coronary microcirculatory function in patients with STEMI8. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is a novel and reliable surrogate for insulin resistance9, which is an independent predictor of cardiovascular prognosis10,11. Previous studies have suggested that a higher TyG index is associated with cardiovascular disease12,13 and poorer prognosis14,15,16,17,18. Ma et al.19 confirmed that a higher TyG index was correlated with an increased risk of no-reflow after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Despite these findings, the specific association between the TyG index and AMR in STEMI patients with T2DM has not been thoroughly investigated. Moreover, a clearer understanding of the TyG index’s role in this population highlights its potential as a non-invasive tool for early identification of patients at higher risk of microcirculatory impairment. This has important implications for clinical practice, as optimizing microcirculatory function could lead to improved myocardial recovery and reduced morbidity and mortality associated with STEMI. Thus, this study aims to fill this critical knowledge gap.

Materials and methods

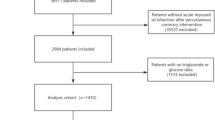

We retrospectively screened 362 consecutive patients who underwent pPCI at Taizhou People’s Hospital from January 2022 to December 2023. The flow diagram of patient selection is detailed in Fig. 1. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients receiving mechanical hemodynamic support; (2) images were of poor quality for analysis; (3) culprit vessel was left main; (4) insufficient clinical data. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. Consent for treatment was obtained from all patients. Informed consent was waived by the institutional review board (Ethics Committee of Taizhou People’s Hospital) because of the retrospective nature of this study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Taizhou People’s Hospital and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collections and definitions

The electronic medical record system collected patient demographics, past medical history (including hypertension, T2DM, smoking, et al.), laboratory data (including hemoglobin, leukocyte, fasting blood-glucose, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, glycosylated hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, high sensitivity troponin I, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide), echocardiographic results, and angiography. Criteria for T2DM included: (1) a previous diagnosis of T2DM on antidiabetic medication; (2) typical diabetic symptoms (excessive thirst and drinking, polyuria, polyphagia, and unexplained weight loss) with a fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, and/or a randomized glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, and/or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%. STEMI was defined using the current guidelines20,21 as follows: (1) chest pain or equivalent symptoms lasting for longer than 30 min and (2) ST-segment elevation in at least two contiguous leads (at least 0.2 mV in men or at least 0.15 mV in women in leads V2–V3 and/or at least 0.1 mV in the other leads) or a new left bundle branch block. The TyG index, which quantifies insulin resistance by combining fasting glucose with triglyceride levels, was calculated using the following formula: TyG = ln [triglycerides (mg/dL) × glucose (mg/dL)/2]19.

When STEMI was confirmed, patients were administered 300 mg aspirin and 180 mg ticagrelor and transferred to the catheter laboratory to receive pPCI. Anticoagulation with heparin (80−100 U/Kg) was performed for all STEMI patients. The interventional cardiologists used a thrombus aspiration catheter and administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor infusion treatment at their discretion. After pPCI, patients were transferred to the coronary care unit for further management. Two certified analysts retrospectively analyzed the angiographic images in a blinded manner. Assessments of AMR were performed using the validated AngioPlus software as described previously22,23,24. Specifically, after selecting the optimal angiographic view to minimize vessel overlap, the lumen contour of the targeted coronary artery is automatically outlined. The velocity of the contrast flow was determined by dividing the length of the vessel’s centerline by the time it took for the contrast to fill, which was then converted into hyperemic flow velocity (Velocityhyp). The analysis frame was required to show adequate contrast fill and a complete view of the lumen contours, enabling automatic delineation of the lumen boundaries for both the target vessel and its major side branches. Utilizing the Murray bifurcation fractal law, the reference diameter of the vessel was reconstructed, accounting for the step-down phenomenon at bifurcations. Subsequently, fluid dynamic equations were applied with the calculated hyperemic flow as a boundary condition to determine the pressure drop. From this pressure drop, the distal coronary pressure (Pd) was derived. The quantitative flow ratio (QFR) was computed by dividing Pd by the mean aortic pressure, while the AMR was determined by dividing Pd by Velocityhyp. Based on the AMR value, patients were divided into a low AMR group (AMR < 2.5) and a high AMR group (AMR ≥ 2.5).

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and number and percentage for categorical variables. The normality of continuous variables was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine differences in continuous variables between groups, as appropriate. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between groups. Multivariate forward logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent factors associated with high AMR. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the performance of the TyG index in predicting high AMR. Results are expressed as odds ratio (OR) with an associated 95% confidence interval (CI). All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

The flowchart of study population is depicted in Fig. 1. We enrolled 168 diabetic STEMI patients undergoing pPCI. The TyG index distribution is shown in Fig. 2. Based on AMR, 87 patients were categorized as high AMR (AMR ≥ 2.5), and the remaining 81 patients were classified as low AMR (AMR < 2.5). Table 1 details the baseline characteristics, revealing that low AMR patients were younger (p = 0.002), had a lower BMI (p = 0.006) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels (p = 0.002), higher hemoglobin, lower prevalence of Killip class ≥ II (p < 0.001), and were more frequently smokers (p = 0.016).

Relationship between TyG index and AMR

Figure 3 shows the association between the TyG index and AMR, with higher TyG index values in high AMR patients compared to low AMR patients (p = 0.001). In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, age (OR: 1.032, 95% CI: 1.066–1.201, and p = 0.032), hemoglobin (OR: 1.006, 95% CI: 1.003–1.009, and p = 0.015), and TyG index (OR: 2.449, 95% CI: 1.421–4.220, and p = 0.001) were significantly associated with high AMR after adjusting for other confounding factors (Table 2).

ROC curve analyses of the TyG index to predict high AMR

The ROC curve analysis indicated an area under the curve of 0.650 (95% CI: 0.57–0.73, p < 0.001; Fig. 4) for the TyG index in predicting high AMR, with a cut-off value of 9.57, sensitivity of 0.644, and specificity of 0.654.

Discussions

This study determined the relationship between AMR and the TyG index in patients with diabetes and STEMI receiving pPCI. Our findings indicate that a higher TyG index is independently associated with elevated AMR, suggesting that insulin resistance may contribute to microcirculatory dysfunction in this population.

The pathological mechanism of impaired coronary microcirculation in patients with STEMI is complex, among which insulin resistance plays an important role. Danijela Trifunovic et al.8 demonstrated that insulin resistance assessed by the Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA) index in the acute phase of myocardial infarction in non-diabetic patients was independently associated with poorer myocardial reperfusion, impaired coronary microcirculatory function and potentially with larger final infarct size. Previous studies have confirmed that insulin resistance is involved in the onset and development of coronary heart disease and is associated with the prognosis of patients with AMI25,26,27,28,29,30. Moreover, insulin resistance is associated with cardiac remodeling after AMI, including ventricular dilatation and worsening cardiac function. Wojciech Zareba et al.25 found that insulin resistance predicted the recurrence of coronary events in the post-infarction population from the thrombogenic factors and recurrent coronary events (THROMBO) study. Juan Sanchis et al. reported that insulin resistance had an important short-term prognostic role in patients with AMI26. Multiple mechanisms could be involved in the association between insulin resistance and microcirculatory resistance. First, insulin resistance is closely related to endothelial dysfunction. Insulin commonly promotes the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator. However, endothelial dysfunction caused by insulin resistance reduces NO synthesis, decreasing vasodilation and increasing microcirculation resistance. Second, systemic inflammation is frequently associated with insulin resistance31,32, which promotes the local accumulation of inflammatory factors (tumor necrosis factor-α and C-reactive protein) and increases microcirculation resistance, resulting in microvascular endothelial injury and dysfunction. Third, insulin resistance can affect the function of vascular smooth muscle cells, resulting in increased contractility and an increase in the baseline tension of the blood vessels, thereby increasing microcirculatory resistance19.

The TyG index is emerging as a novel alternative marker of insulin resistance that is highly practical and cost-effective, particularly in clinical practice33. The degree of insulin resistance is reflected by the TyG index, which exhibits consistency and stability across various clinical settings18,19,34. Prior researches have linked the TyG index to various cardiovascular outcomes, including chest pain incidence and mortality in the U.S. population35, underscoring its potential role in identifying at-risk individuals. Additionally, the TyG index has been explored as a screening tool for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis, with certain parameters demonstrating predictive value for these conditions36. Importantly, the association between the TyG index and impaired cardiovascular fitness has been documented in non-diabetic young populations37, indicating that elevated triglycerides and glucose levels can negatively impact cardiovascular health. In patients with STEMI, hyperglycemia has been shown to drive stent restenosis38, further highlighting the relevance of metabolic dysregulation in acute cardiac events. The predictive performance of the TyG index in identifying glucose status conversion supports its utility in clinical settings, where timely intervention can alter disease trajectories39. Moreover, prediabetes has been identified as a risk factor for frailty among prefrail older adults with hypertension40. Recent findings suggest that changes in the TyG index may predict stroke incidence in individuals over 4541, reinforcing its potential as a public health screening tool. Furthermore, both elevated and reduced levels of TyG are associated with an increased prevalence of heart failure with diabetes and prediabetes42. Interestingly, elevated TyG index at baseline and long-term TyG index trajectories were found to be associated with the risk of hypertension, suggesting early identification of increasing TyG index could provide insights for preventing hypertension later in life43. A cohort study by Zhenhong Fu et al. reported that in 231 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and diabetes mellitus, the TyG index predicted the risk of all-cause mortality in the oldest-old ACS patients with diabetes mellitus17. Ning Yan et al. found that the TyG index was positively correlated with no-flow in patients with T2DM and AMI in a study that included 1683 patients with T2DM and AMI who underwent pPCI19, consistent with our findings. TyG index is a comprehensive reflection of triglyceride and blood glucose levels. Elevated triglyceride levels are frequently associated with abnormal lipid metabolism, affecting vascular smooth muscle function44. Abnormal lipid metabolism can result in excessive contraction of vascular smooth muscle cells, thereby increasing microcirculation resistance45. Previous studies have verified the TyG index’s effectiveness in determining insulin resistance46. This study further confirmed the independent predictive ability of the TyG index for microcirculatory resistance in patients with diabetes and STEMI undergoing pPCI. This finding offers a novel perspective for understanding the association between diabetes and microcirculation in patients with STEMI. We used the ROC curve analysis to evaluate the predictive performance of the TyG index and found the cut-off value of 9.57 for the TyG index. This specific threshold demonstrates a balance between sensitivity and specificity, effectively identifying patients with heightened insulin resistance who may be at greater risk for elevated microcirculatory resistance. This threshold has clinical implications, as it can serve as a practical tool for clinicians in routine assessments. Patients with a TyG index above 9.57 may warrant closer monitoring and more aggressive management of cardiovascular risk factors, potentially leading to better outcomes.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this was a single-center, retrospective analysis, which may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability. The relatively small sample size restricts the statistical power to detect subtle associations. Second, AMR was applied to determine microcirculatory resistance based on a single angiographic view. However, the feasibility of this novel computational approach has been previously validated23. Third, while we measured triglyceride and fasting blood glucose levels at admission, fluctuations during hospitalization or follow-up were not assessed, which could affect microcirculatory resistance. Lastly, while the TyG index offers convenience and ease of use in clinical practice, it is less specific than direct insulin measurement methods. For instance, HOMA-IR requires fasting insulin levels, which can provide a more accurate assessment of insulin sensitivity, but it also necessitates more intensive blood sampling. The euglycemic- hyperinsulinemic clamp, considered the gold standard, provides precise measurements of insulin action but is labor-intensive and not practical in routine clinical settings.

In conclusion, while our findings suggest a significant relationship between the TyG index and microcirculatory resistance in diabetic STEMI patients, further research is needed to validate these associations in larger, more diverse cohorts. Future studies should also explore the underlying mechanisms linking insulin resistance to microcirculatory dysfunction and the clinical implications of the TyG index in various cardiovascular diseases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cioffi, G. M. et al. Mitigating the risk of flow deterioration by deferring stent optimization in STEMI patients with large thrombus burden: insights from a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 506. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03540-0 (2023).

Heusch, G. Coronary microvascular obstruction: the new frontier in cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 114 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-019-0756-8 (2019).

Watanabe, Y. et al. Determinants of slow flow following stent implantation in intravascular ultrasound-guided primary percutaneous coronary intervention. 33, 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-017-1050-z (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Coronary angiography-derived index of Microcirculatory Resistance Associated with New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in patients with STEMI. Can. J. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2023.10.025 (2023).

Palmer, S. et al. The index of Microcirculatory Resistance Postpercutaneous coronary intervention predicts left ventricular recovery in patients with Thrombolyzed ST-Segment Elevation myocardial infarction. 29, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/joic.12271 (2016).

Mehdipoor, G. et al. Hypertension, microvascular obstruction and infarct size in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI: pooled analysis from 7 cardiac magnetic resonance imaging studies. Am. Heart J. 271, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2024.02.023 (2024).

Silva, M., Paiva, L., Teixeira, R., Ferreira, M. J. & Goncalves, L. Microcirculation function assessment in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review of microcirculatory resistance indices. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1041444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1041444 (2022).

Trifunovic, D. et al. Acute insulin resistance in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in non-diabetic patients is associated with incomplete myocardial reperfusion and impaired coronary microcirculatory function. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 13, 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-13-73 (2014).

Sánchez-García, A. et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Triglyceride and Glucose Index for Insulin Resistance: A Systematic Review. International journal of endocrinology 4678526, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4678526 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index in the prediction of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with premature coronary artery disease: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01576-8 (2022).

Ramdas Nayak, V. K., Satheesh, P., Shenoy, M. T. & Kalra, S. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: a surrogate biomarker of insulin resistance. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 72, 986–988. https://doi.org/10.47391/jpma.22-63 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index variability and incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01541-5 (2022).

Wan, Y. et al. Association of triglyceride-glucose index with cardiovascular disease among a general population: a prospective cohort study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01181-z (2023).

Dang, K. et al. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indicators and cardiovascular disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02115-9 (2024).

Shali, S. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is associated with severe obstructive coronary artery disease and atherosclerotic target lesion failure among young adults. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02004-1 (2023).

Li, J. et al. The triglyceride-glucose index is associated with atherosclerosis in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease, regardless of diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01919-z (2023).

Shen, J. et al. Triglyceride glucose index predicts all-cause mortality in oldest-old patients with acute coronary syndrome and diabetes mellitus. BMC Geriatr. 23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03788-3 (2023).

Liu, Q. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Kailuan study. Endocrine 75, 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-021-02862-3 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Predictive effect of triglyceride-glucose index on No-Reflow Phenomenon in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 16, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-024-01306-y (2024).

Ibanez, B. et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 39, 119–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 (2018).

O’Gara, P. T. et al. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 127, e362-425, (2013). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6 (2013).

Tu, S. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative flow ratio for assessment of coronary stenosis significance from a single angiographic view: a novel method based on bifurcation fractal law. 1040–1047. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.29592 (2021).

Fan, Y. et al. In vivo validation of a Novel Computational Approach to assess Microcirculatory Resistance based on a single angiographic view. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111798 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a fast Computational Approach to Derive Fractional Flow Reserve from coronary CT angiography. 13, 172–175, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.08.003

Szepietowska, B. et al. Insulin resistance predicts the risk for recurrent coronary events in post-infarction patients. Cardiol. J. 22, 519–526. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2015.0014 (2015).

Sanjuan, R. et al. Insulin resistance and short-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 172, e269–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.207 (2014).

Smit, J. W. & Romijn, J. A. Acute insulin resistance in myocardial ischemia: causes and consequences. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 10, 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089253206291153 (2006).

Karrowni, W. et al. Insulin resistance is associated with significant clinical atherosclerosis in nondiabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 2245–2251. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.113.301585 (2013).

Hedblad, B., Nilsson, P., Engström, G., Berglund, G. & Janzon, L. Insulin resistance in non-diabetic subjects is associated with increased incidence of myocardial infarction and death. Diabet. Medicine: J. Br. Diabet. Association. 19, 470–475. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00719.x (2002).

Gerstein, H. C., Ferrannini, E., Riddle, M. C. & Yusuf, S. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular outcomes in the ORIGIN trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 20, 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13112 (2018).

Picchi, A. et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: a review. World J. Cardiol. 2, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v2.i11.377 (2010).

Shoelson, S. E., Lee, J. & Goldfine, A. B. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 1793–1801. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci29069 (2006).

Xiang, Q. et al. Association between the Triglyceride-Glucose Index and Vitamin D Status in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030639 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Triglyceride glucose-body mass index as a novel predictor of slow coronary flow phenomenon in patients with ischemia and nonobstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-03722-4 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Gu, Y. & Zhang, B. Associations of triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index with chest pain incidence and mortality among the U.S. population. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02209-y (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose related indices and mortality among individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02343-7 (2024).

Guo, D. et al. Association between the triglyceride-glucose index and impaired cardiovascular fitness in non-diabetic young population. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02089-8 (2024).

Guo, X., Shen, R., Yan, S., Su, Y. & Ma, L. Triglyceride-glucose index for predicting repeat revascularization and in-stent restenosis in patients with chronic coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01779-7 (2023).

Chen, X., Liu, D., He, W., Hu, H. & Wang, W. Predictive performance of triglyceride glucose index (TyG index) to identify glucose status conversion: a 5-year longitudinal cohort study in Chinese pre-diabetes people. J. Translational Med. 21, 624. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04402-1 (2023).

Santulli, G. et al. Prediabetes increases the risk of Frailty in Prefrail older adults with hypertension: Beneficial effects of Metformin. Hypertens. (Dallas Tex. : 1979). 81, 1637–1643. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.124.23087 (2024).

Huo, R. R., Liao, Q., Zhai, L., You, X. M. & Zuo, Y. L. Interacting and joint effects of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) and body mass index on stroke risk and the mediating role of TyG in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02122-4 (2024).

Shi, Y. & Yu, C. U shape association between triglyceride glucose index and congestive heart failure in patients with diabetes and prediabetes. Nutr. Metabolism. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-024-00819-7 (2024).

Xin, F. et al. The triglyceride glucose index trajectory is associated with hypertension: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 347. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02087-w (2023).

Trovati, M. & Anfossi, G. Influence of insulin and of insulin resistance on platelet and vascular smooth muscle cell function. J. Diabetes Complicat. 16, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1056-8727(01)00196-9 (2002).

Padró, T., Vilahur, G. & Badimon, L. Dyslipidemias and Microcirculation. Curr. Pharm. Design. 24, 2921–2926. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180702154129 (2018).

Tahapary, D. L. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome. 16, 102581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102581 (2022).

Funding

This study was supported by the clinical research project of Taizhou clinical college of medicine of Nanjing Medical University (TZKY20230207).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and G.W.; methodology, G.W; software, C.X.; validation, C.X. and Z.T.; formal analysis, Z.T. and J.W.; data curation, Z.T. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.W; writing—review and editing, C.X., L.Z. and G.W.; supervision, X.S., K.X. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. Consent for treatment was obtained from all patients. Informed consent was waived because this was a retrospective study according to the institutional review board (Ethics Committee of Taizhou People’s Hospital).

Consent for publication

If the manuscript is accepted, we approve it for publication in Scientific Reports.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Xu, C., Wang, J. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is associated with microcirculatory resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes and STEMI undergoing primary PCI. Sci Rep 15, 4723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89269-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89269-6